Abstract

Swarming contributes to Proteus mirabilis pathogenicity by facilitating access to the catheterized urinary tract. We previously demonstrated that 0.1–20 mmol/L arginine promotes swarming on normally nonpermissive media and that putrescine biosynthesis is required for arginine-induced swarming. We also previously determined that arginine-induced swarming is pH dependent, indicating that the external proton concentration is critical for arginine-dependent effects on swarming. In this study, we utilized survival at pH 5 and motility as surrogates for measuring changes in the proton gradient (ΔpH) and proton motive force (μH+) in response to arginine. We determined that arginine primarily contributes to ΔpH (and therefore μH+) through the action of arginine decarboxylase (speA), independent of the role of this enzyme in putrescine biosynthesis. In addition to being required for motility, speA also contributed to fitness during infection. In conclusion, consumption of intracellular protons via arginine decarboxylase is one mechanism used by P. mirabilis to conserve ΔpH and μH+ for motility.

Keywords: Arginine decarboxylase, Proteus mirabilis, proton motive force, swarming, swimming, UTI

Introduction

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is one of the most common infections worldwide and causes a significant healthcare burden, with ∼50% of women and 12% of men experiencing a UTI in their lifetime (Foxman and Brown 2003; Klevens et al. 2007; Foxman 2010). In addition to uncomplicated UTI, the majority of patients undergoing long-term catheterization will experience at least one episode of catheter-associated UTI (CaUTI), making it the most common hospital-acquired infection (Morris et al. 1999; Jacobsen et al. 2008; Hooton et al. 2010). If the UTI does not resolve, resulting complications can include the development of acute pyelonephritis and bacteremia.

The Gram-negative bacterium Proteus mirabilis is responsible for ∼3% of all nosocomial infections in the United States and up to 44% of CaUTIs (O’Hara et al. 2000; Nicolle 2005; Jacobsen et al. 2008). Proteus mirabilis possesses numerous virulence factors that contribute to the establishment of UTI (Coker et al. 2000; Jacobsen et al. 2008; Armbruster and Mobley 2012). In addition to typical virulence factors, P. mirabilis differentiates into elongated swarm cells capable of migrating across catheters to reach the bladder (Stickler and Hughes 1999; Sabbuba et al. 2002; Jacobsen et al. 2008).

Current research has revealed a complex regulatory network governing swarm cell differentiation, with most factors acting on the flagellar master regulator FlhD2C2 as described in recent reviews (Rather 2005; Morgenstein et al. 2010; Armbruster and Mobley 2012). However, little is known concerning how P. mirabilis coordinates swarm cell differentiation and migration. Swarming appears to be cell-density dependent, yet known quorum sensing systems are not involved (Belas et al. 1998; Schneider et al. 2002). The polyamine putrescine has been proposed as a signaling molecule for coordination of swarming in P. mirabilis as migration of the swarm requires putrescine synthesis via arginine decarboxylase (SpeA) and agmatinase (SpeB) (Sturgill and Rather 2004; Armbruster et al. 2013), as well as putrescine uptake via PlaP (Kurihara et al. 2013). Putrescine is also a component of the core region of P. mirabilis lipopolysaccharide (Vinogradov and Perry 2000) and may be important for changes in cell wall composition during differentiation.

In an endeavor to understand how P. mirabilis determines when an environment is permissive for swarming, we previously identified five cues present in normal human urine capable of inducing motility under normally nonpermissive conditions (Armbruster et al. 2013). One of the cues, l-arginine, contributes to the primary pathway for putrescine biosynthesis through a two-step reaction: arginine decarboxylase (speA) converts arginine to agmatine and agmatinase (speB) converts agmatine to putrescine (Pearson et al. 2008). Putrescine is critical for swarming, and must be produced through this pathway or exogenously supplied and imported in order for P. mirabilis to migrate across permissive media (Sturgill and Rather 2004; Armbruster et al. 2013; Kurihara et al. 2013). We previously showed that this pathway must also be intact or complemented by the addition of exogenous putrescine for swarming to occur under normally nonpermissive conditions in response to swarming cues such as arginine (Armbruster et al. 2013). However, the ability of arginine to promote swarming appears separate from the generation of putrescine as other components of this pathway, including agmatine and putrescine itself, were not capable of promoting swarming under the conditions tested (Armbruster et al. 2013). Thus, arginine may promote swarming through an additional mechanism independent of its role in putrescine biosynthesis.

Proteus mirabilis swarming is known to be intimately connected to energy metabolism (Armitage 1981; Alteri et al. 2012), which is not surprising considering that flagellar rotation is dependent on proton motive force (μH+) (Gabel and Berg 2003). As swarm cells exhibit increased flagellum density and are capable of faster movement than vegetative cells (Tuson et al. 2013), a substantial μH+ is likely required to fuel rotation of the hundreds to thousands of flagella expressed by P. mirabilis swarm cells. Metabolic activity is highest when P. mirabilis is preparing to swarm and surprisingly low during actual migration, indicating that swarm cells are almost entirely devoted to flagellar-mediated motility during swarm front migration (Armitage 1981; Pearson et al. 2010). The energy used to fuel swarming was previously thought to be generated through fermentation (Falkinham and Hoffman 1984), which is unusual as fermentation is not as energetically favorable as respiration. Under aerobic conditions, oxygen is used as the terminal electron acceptor and the greatest number of protons can be pumped across the cytoplasmic membrane through the respiratory chain, producing a strong μH+. Under anaerobic conditions, an alternative electron acceptor can be used for the respiratory chain, but the process releases less energy. During fermentation, however, ATP must be consumed to pump protons and conserve the pH and charge gradients (ΔpH and Δψ), making it difficult to maintain μH+ and fuel flagellar rotation.

To address this issue, recent work in our laboratory investigated the ability of P. mirabilis to use a complete oxidative tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle during swarming under aerobic conditions without apparently requiring oxygen as the terminal electron acceptor (Alteri et al. 2012). Based on this study, it was proposed that P. mirabilis maintains μH+ and drives flagellar rotation through the oxidative TCA cycle while using an anaerobic respiratory chain in which fumarate metabolism plays a critical role (Alteri et al. 2012). However, it was still not clear how P. mirabilis could support the magnitude of μH+ required to fuel swarming using an anaerobic respiratory chain.

Notably, arginine metabolism can influence both components of μH+ (ΔpH and Δψ) through a mechanism that is used by some bacterial species to tolerate acidic conditions (Foster 2004). Arginine decarboxylase replaces the α-carboxyl group of arginine (+1 charge) with a proton recruited from the cytoplasm to generate agmatine (+2 charge), thus consuming an intracellular proton and therefore contributing to ΔpH (Gong et al. 2003; Foster 2004). Agmatine export can then be coupled to arginine import, influencing Δψ. Acid-tolerant bacteria utilize this and related systems to alter membrane potential and impede movement of external protons across the membrane, thereby allowing for survival in acidic environments. While P. mirabilis is not known to be acid-tolerant, it may utilize arginine decarboxylation to contribute to μH+ in a similar manner.

In this study, we utilized mutants defective in arginine transport or putrescine biosynthesis to elucidate one mechanism by which arginine promotes motility and fitness. Using survival at pH 5 and motility as surrogates for measuring changes in the proton gradient (ΔpH) and proton motive force (μH+), we determined that arginine contributes to conservation of μH+ and that arginine decarboxylase (speA) contributes to P. mirabilis swimming and swarming motility independent of its role in putrescine biosynthesis. Loss of speA also resulted in a fitness defect that was not observed for a speBF double mutant lacking both routes for putrescine biosynthesis. We thus conclude that consumption of intracellular protons via arginine decarboxylation is one mechanism used by P. mirabilis to conserve ΔpH and μH+ to support motility. This mechanism may also shed light on how P. mirabilis supports vigorous swarming while utilizing an anaerobic respiratory chain.

Experimental Procedures

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

Strains used in this study are listed in Table1. Bacteria were routinely cultured at 37°C with aeration. Swarming on permissive medium was assessed using swarm agar (10 g L−1 tryptone, 5 g L−1 yeast extract, 5 g L−1 NaCl solidified with 1.5% agar), which will be referred to as SWA, supplemented with various concentrations of l-arginine (Research Products International Corp., Mount Prospect, IL, USA). Media were supplemented with chloramphenicol (20 μg mL−1), ampicillin (100 μg mL−1), and kanamycin (25 μg mL−1) as required.

Table 1.

Proteus mirabilis strains and constructs used in this study.

| Strain | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| HI4320 | Proteus mirabilis isolated from the urine of an elderly, long-term–catheterized woman | Mobley and Warren (1987) |

| speA | KanR insertion disrupting arginine decarboxylase | This study |

| speB | KanR insertion disrupting agmatinase | Armbruster et al. (2013) |

| speBF | KanR insertion disrupting ornithine decarboxylase was excised and an additional KanR was inserted into agmatinase | Armbruster et al. (2013) |

| artM | KanR insertion disrupting the arginine transporter permease subunit | This study |

| ydgI | KanR insertion disrupting an arginine:ornithine antiporter | This study |

Construction of mutants

TargeTron (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) was utilized to insert a kanamycin resistance cassette into genes of interest according to the manufacturer's instructions as described previously (Pearson and Mobley 2007). Primer sequences for intron reprogramming and PCR verification of mutants are provided in Table S1.

Growth curves

Overnight cultures of bacteria were diluted 1:100 in Luria broth (LB, 10 g L-1 tryptone, 5 g L-1 yeast extract, 0.5 g L-1 NaCl). Where indicated, LB was supplemented with 10 or 20 mmol/L arginine, buffered with 10 mmol/L 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES; Sigma), and adjusted to pH 5 or 7. A Bioscreen-C Automated Growth Curve Analysis System (Growth Curves, USA) was utilized to generate growth curves. Cultures were incubated at 37°C with continuous shaking, and OD600 readings were taken every 15 min for 17–24 h.

Swarming motility

SWA plates (with or without arginine, agmatine, and putrescine) were inoculated with 5 μL of an overnight culture. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 18 h, and swarm colony diameter was measured.

Acid resistance experiments

Overnight cultures were diluted 1:50 into 5 mL LB and cultured at 37°C with aeration to log phase (2–3 h). Cultures were centrifuged (16,060g, 5 min, 25°C) and resuspended in 10 mmol/L 2-(N-morpholino)-ethanesulfonic acid (MES; Sigma) buffer to an OD600 of ∼1.0. The bacterial suspension was diluted 1:10 into 1 mL of 10 mmol/L MES adjusted to pH 7, 5, or 2.5 using HCl and KOH, with or without 20 mmol/L arginine. Carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP; 100 μmol/L) diluted in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added as indicated to depolarize the inner membrane, and control cultures were incubated with DMSO alone. Samples were incubated at 37°C with aeration for 1 h and plated to determine CFU mL−1 using an Autoplate 4000 spiral plater (Spiral Biotech, Norwood, MA, USA). Colonies were enumerated using a QCount automated plate counter (Spiral Biotech).

pH of overnight cultures

Overnight cultures of P. mirabilis HI4320 and speA were diluted 1:100 into 3 mL LB buffered with 10 mmol/L HEPES and adjusted to pH 5 with concentrated HCl or KOH after the addition of 10 or 20 mmol/L arginine. Cultures were incubated at 37°C with aeration. After 18 h, pH was determined to the nearest increment of 0.5 using pH test paper (Fisherbrand, Pittsburgh, PA, USA).

Swimming motility

Motility agar plates (MOT, 10 g L−1 tryptone, 0.5 g L−1 NaCl, 3 g L−1 agar) with or without 20 mmol/L arginine were stab inoculated with an overnight culture of P. mirabilis or isogenic mutants. MOT plates were incubated at 30°C for 18 h prior to measurement of swimming diameter.

Effect of arginine on μH+ during swimming and swarming

Six-millimeter blank paper disks (BD) were impregnated with 10 μL of 10 mmol/L CCCP or DMSO as a negative control and placed on SWA or MOT with or without 20 mmol/L arginine. SWA plates were inoculated with 5 μL from an overnight culture and incubated at 37°C for 18 h, and MOT plates were stab inoculated from an overnight culture and incubated at 30°C for 18 h. The zone of inhibition of motility was measured by determining the distance (mm) from the swarm or swim edge to the outermost edge of the disk. For experiments using the speA mutant, 50 μL of 50 mmol/L putrescine was spread on SWA plates to chemically complement swarming defects.

Mouse model of ascending UTI

Co-challenge experiments with CBA/J mice were carried out as described previously (Johnson et al. 1987) using a modification of the Hagberg et al. (1983) protocol. Briefly, bacteria were cultured overnight in 5 mL LB, diluted to an OD600 of ∼0.2, mixed 1:1, and mice were inoculated transurethrally with 50 μL of 2 × 108 CFU mL−1 (1 × 107 CFU per mouse). Mice were euthanized 7 days postinoculation and urine, bladder, and kidneys were harvested and transferred into sterile tubes containing 3 mL phosphate-buffered saline (0.128 mol/L NaCl, 0.0027 mol/L KCl, pH 7.4). Tissues were homogenized using an Omni TH homogenizer (Omni International Kennesaw, GA, USA) and plated onto LB agar using an Autoplate 4000 spiral plater (Spiral Biotech). Colonies were enumerated with a QCount automated plate counter (Spiral Biotech). A competitive index (CI) was calculated for each organ with a bacterial load greater than the limit of detection by determining the ratio of mutant to wild type as follows:

A CI of 1 indicates that the mutant colonized the organ to a similar level as P. mirabilis HI4320, a CI <1 indicates that the mutant was outcompeted by wild type, and a CI >1 indicates that wild type was outcompeted by the mutant.

Statistics

Significance was determined by unpaired Student's t-test, two-way ANOVA, and the Wilcoxon signed rank test as indicated. All P values are two tailed at a 95% confidence interval. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism, version 6.04 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

Arginine contributes to ΔpH and μH+

We previously determined that arginine was most effective at promoting swarming when agar was mildly acidic and less effective when external pH increased (Armbruster et al. 2013). This observation suggests that swarming in response to arginine is related to proton distribution, and therefore possibly proton motive force (μH+). To directly measure an effect on μH+, we first attempted to use the carbocyanine dye 3,3′-diethyloxacarbocyanine iodide (DiOC2), which self-associates at high intracellular concentrations (Sims et al. 1974). However, μH+ could not be measured with this technique as P. mirabilis HI4320 failed to take up DiOC2 under all conditions tested, even when outer membrane integrity was compromised by incubation with EDTA (data not shown).

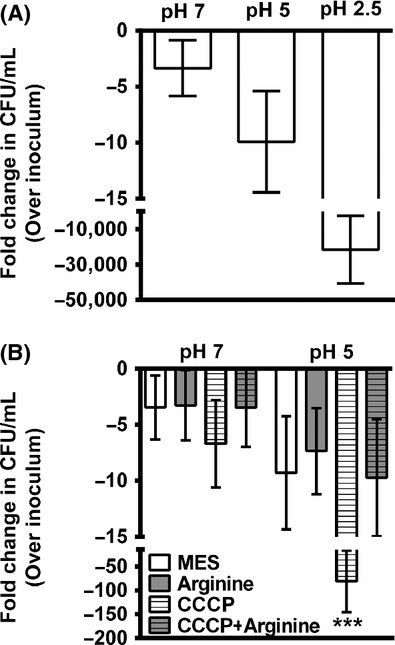

As bacteria can modulate ΔpH and/or Δψ to promote survival during exposure to acidic conditions (Foster 2004), an alternate method for observing changes in the proton gradient (and therefore μH+) involves tolerance of acidic conditions. To first determine whether P. mirabilis tolerates acidity, P. mirabilis HI4320 was incubated for 60 min in MES buffer adjusted to pH 7, 5, or 2.5 (Fig.1A). Proteus mirabilis HI4320 was not able to maintain viability during incubation at pH 2.5. However, incubation at pH 5 was tolerated with only a modest decrease in viability. We can therefore utilize survival in pH 5 MES buffer to investigate the contribution of arginine to conservation of the proton gradient and μH+.

Figure 1.

Arginine contributes to μH+ in Proteus mirabilis. (A) Proteus mirabilis HI4320 was incubated for 60 min in 10 mmol/L MES buffer at pH 7, 5, or 2.5, and fold change in CFU mL−1 were determined. Error bars indicate mean ± SD for five independent experiments. (B) Proteus mirabilis HI4320 was incubated for 60 min in 10 mmol/L MES buffer at pH 7 or 5. Viable bacteria were enumerated for MES buffer with and without 10 mmol/L CCCP and 20 mmol/L arginine. CFU mL−1 were normalized to the inoculum. Error bars represent fold change over CFU mL−1 in the inoculum ± SD for at least three independent experiments. ***P < 0.001 by Student's t-test compared to incubation in unsupplemented pH 5 MES.

Viability at pH 5 was next tested in the presence of the protonophore chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP), which depolarizes the electrochemical gradient across the inner membrane thereby collapsing membrane potential and μH+ (Fig.1B). Importantly, neither CCCP nor arginine significantly impacted viability during incubation in pH 7 MES buffer. However, depolarization of the membrane in pH 5 MES buffer resulted in a dramatic decrease in viability, and this effect was abrogated in the presence of 20 mmol/L arginine. The data therefore indicate that P. mirabilis can utilize arginine to conserve membrane potential and μH+.

Arginine decarboxylase is required for arginine-dependent effects on ΔpH and μH+

Our previous data indicated that arginine may promote swarming through an additional mechanism independent of its role in putrescine biosynthesis (Armbruster et al. 2013). Based on the ability of arginine to counteract the effects of CCCP, P. mirabilis is clearly capable of utilizing this amino acid to influence membrane potential, possibly through the action of arginine decarboxylase (speA). Arginine decarboxylase contributes to the distribution of protons across the membrane (ΔpH) as this reaction consumes a cytoplasmic proton during generation of agmatine (Gong et al. 2003; Foster 2004). Acid-tolerant bacteria can utilize this reaction and an arginine:agmatine antiporter as one mechanism for altering membrane potential (and therefore μH+) to impede movement of external protons across the membrane, thereby allowing for survival in acidic environments. Even though P. mirabilis HI4320 was not acid tolerant (Fig.1), it may utilize arginine decarboxylation through a similar mechanism to contribute to μH+ for survival in the presence of CCCP at pH 5.

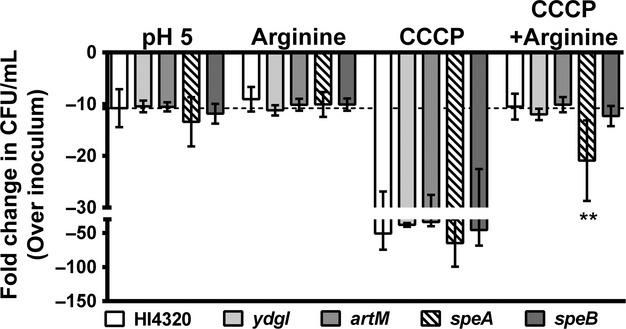

Proteus mirabilis HI4320 does not encode a homolog of the Escherichia coli or Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium arginine:agmatine antiporter (adiC), but it does encode an arginine:ornithine antiporter (ydgI) with 26% identity to E. coli AdiC by blastx, as well as the Art system for arginine import. To investigate genetic requirements for arginine-dependent survival at pH 5 in the presence of CCCP, insertion mutants of speA, ydgI, and artM were generated using TargeTron and tested for survival at pH 5 (Fig.2). All of the mutants tolerated incubation at pH 5 and the presence of arginine to a similar extent as P. mirabilis HI4320, and all exhibited a decrease in viability during incubation with CCCP. Importantly, arginine protected all mutants from the effects of CCCP except speA, which exhibited significantly reduced viability compared to P. mirabilis HI4320 and to incubation in pH 5 MES with arginine. Notably, the arginine transporter mutants artM and ydgI did not exhibit defects, suggesting that the presence of either transporter is sufficient for importing arginine and an antiport mechanism is not required under these conditions. These data therefore support a role for l-arginine and arginine decarboxylase in conservation of the proton gradient and μH+. Attempts to generate an artM/ydgI double mutant were not successful (data not shown), so the role of arginine transport in conservation of μH+ could not be confirmed.

Figure 2.

Arginine decarboxylase contributes to μH+. Proteus mirabilis and isogenic mutants were incubated for 60 min in 10 mmol/L MES buffer at pH 5. Viable bacteria were enumerated for MES buffer with and without 10 mmol/L CCCP and 20 mmol/L arginine. CFU mL−1 were normalized to the inoculum. Dashed line indicates P. mirabilis HI4320 viability in MES buffer at pH 5 without supplement. Error bars represent fold change over CFU mL−1 in the inoculum ± SD for at least four independent experiments. **P < 0.001 by Student's t-test compared to P. mirabilis CCCP plus arginine, speA CCCP, and speA arginine.

To verify that the contribution of speA to proton distribution observed in these experiments with MES buffer are applicable to LB, P. mirabilis HI4320 and the speA mutant were cultured in lightly buffered LB broth adjusted to pH 5 after supplementation with 10 or 20 mmol/L arginine, and supernatant pH was measured following overnight incubation (Table2). We observed that P. mirabilis HI4320 raises the pH to ∼7 during overnight culture and supplementation with arginine promoted further alkalinization to pH ∼8.5, both of which were dependent on speA. Similar results were obtained when measuring growth in pH 5 LB broth, although it is important to note that the speA mutant did not exhibit a growth defect at pH 7 (Fig. S1). Thus, arginine and arginine decarboxylase contribute to proton distribution and alkalinization of LB.

Table 2.

Culture pH following overnight incubation.

| Strain | pH 5 LB | 10 mmol/L arginine | 20 mmol/L arginine | P value1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HI4320 | 7.35 ± 1.88 | 8.06 ± 1.61 | 8.69 ± 0.46 | – |

| speA | 5.19 ± 0.35 | 5.83 ± 1.60 | 6.87 ± 1.90 | 0.0001 |

Determined by two-way ANOVA.

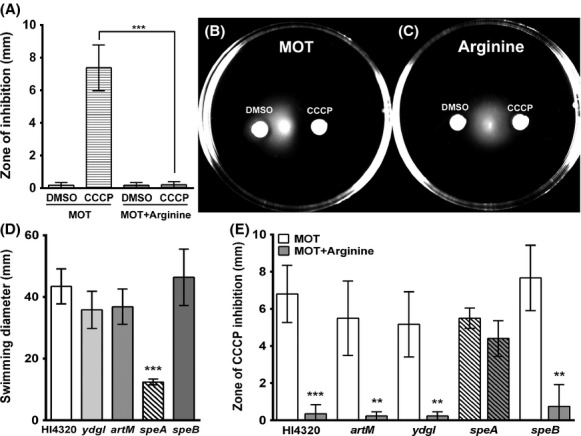

SpeA contributes to conservation of ΔpH and μH+ during swimming

Swimming motility requires μH+ to fuel flagellar rotation (Gabel and Berg 2003), and this form of motility is inhibited when membrane potential is disrupted by CCCP. To demonstrate that arginine contributes to motility through conservation of μH+, we next tested the ability of arginine to counter inhibition of swimming in motility agar (MOT) by CCCP (Fig.3). As expected, disks containing only DMSO had no effect on swimming, but CCCP inhibited motility as evidenced by development of a zone of inhibition extending ∼7 mm from the disk (Fig.3A and B). Importantly, swimming was not inhibited in plates containing arginine (Fig.3A and C). Thus, arginine counters the effect of CCCP and allows P. mirabilis to continue swimming.

Figure 3.

Arginine promotes swimming through conservation of μH+. (A–C) Motility agar plates (MOT) with or without 20 mmol/L arginine were stab inoculated with Proteus mirabilis HI4320. Disks impregnated with DMSO or 10 mmol/L CCCP were placed on the surface of the plates, and the zone of inhibition of motility was measured after an 18 h incubation at 30°C. (A) Measurement of the zone of inhibition of swimming. Error bars represent mean ± SD for four independent experiments with three replicates each. ***P < 0.001 by Student's t-test. (B) Representative image of P. mirabilis HI4320 swimming in MOT. (C) Representative image of P. mirabilis HI4320 swimming in MOT supplemented with arginine. (D) Swimming diameter was measured for P. mirabilis HI4320 and isogenic mutants after an 18-h incubation at 30°C, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 by Student's t-test compared to P. mirabilis HI4320. (E) Measurement of the zone of inhibition of swimming for P. mirabilis HI4320 and isogenic mutants in MOT agar with or without 20 mmol/L arginine. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 by Student's t-test compared to MOT.

As swimming requires μH+, mutations that influence μH+ should affect motility and interfere with the ability of arginine to rescue swimming in the presence of CCCP. Total swimming diameter was first measured for P. mirabilis HI4320 and isogenic mutants (Fig.3D). The only mutant that exhibited decreased swimming diameter was speA, while loss of speB did not affect swimming diameter, indicating that the role of speA in conservation of ΔpH and μH+ can be separated from its role in putrescine biosynthesis. Supplementation with arginine failed to significantly alleviate the inhibitory effects of CCCP for the speA mutant while swimming was restored for all other mutants, including speB (Fig. 3E).

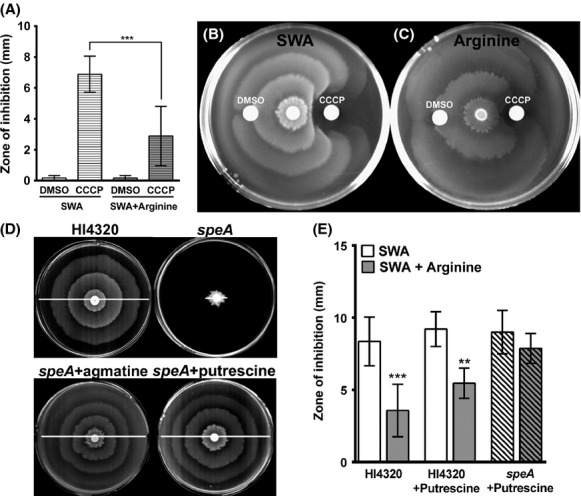

SpeA contributes to conservation of ΔpH and μH+ during swarming

Swarming also requires μH+ but is more complex due to the requirement for differentiation to an elongated swarm cell and multicellular interactions. We therefore wanted to determine whether CCCP also inhibits swarming, and whether inhibition could be similarly alleviated by arginine. DMSO did not perturb swarming, but a zone of inhibition was visible around disks containing CCCP (Fig.4A and B). Similar to swimming motility, arginine significantly decreased inhibition of swarming by CCCP (Fig.4A and C), indicating that P. mirabilis can utilize arginine to promote swarming by conserving ΔpH and μH+.

Figure 4.

Arginine and arginine decarboxylase promote swarming through conservation of μH+. (A–C) SWA with or without 20 mmol/L arginine were inoculated with Proteus mirabilis HI4320. Disks impregnated with DMSO or 10 mmol/L CCCP were placed on the surface of the plates and the zone of inhibition of motility was measured. (A) Measurement of the zone of inhibition of swarming. Error bars represent mean ± SD for four independent experiments with three replicates each. ***P < 0.001 by Student's t-test. (B) Representative image of swarming on SWA. (C) Representative image of swarming on SWA supplemented with arginine. (D) Representative images of SWA plates inoculated with P. mirabilis HI4320 and isogenic mutants after incubation at 37°C for 18 h. The speA mutant was chemically complemented by 20 mmol/L agmatine or by spreading 50 μL of 50 mmol/L putrescine on the surface of the plate. White lines indicate total swarm diameter. (E) Measurement of the zone of inhibition of swarming for P. mirabilis HI4320 and speA. Where indicated, 50 μL of 50 mmol/L putrescine was spread on the surface of the plates. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 by Student's t-test.

We next wanted to determine whether speA contributes to conservation of ΔpH and μH+ during swarming. Consistent with previous reports (Sturgill and Rather 2004), the speA mutant exhibited a severe swarming defect that could be chemically complemented with putrescine (Fig.4D). Swarming was also complemented by agmatine, confirming that the speA mutation is not polar on speB (Fig.4D). Thus, we can complement the swarming defects of the speA mutant with putrescine to determine whether arginine decarboxylase contributes to alleviation of the inhibitory effects of CCCP on SWA supplemented with arginine. Importantly, arginine failed to significantly reduce the zone of CCCP inhibition of swarming for the speA mutant (Fig.4E). Arginine decarboxylase is therefore critical for the arginine-dependent contribution to ΔpH and μH+ during swarming.

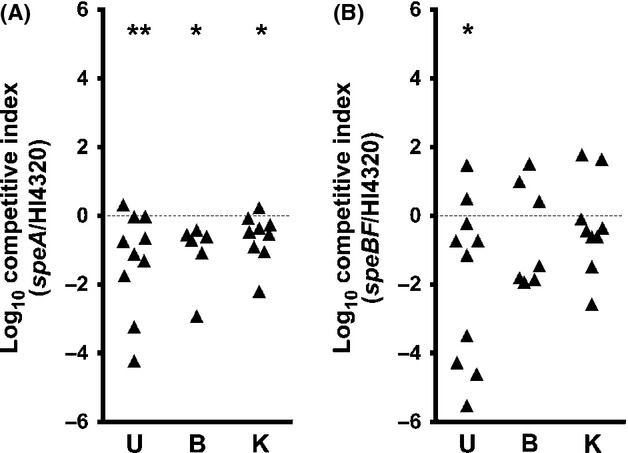

Arginine decarboxylase contributes to P. mirabilis fitness during infection

On the basis of the contribution of arginine and speA to motility and prolonged survival at pH 5, we hypothesized that arginine decarboxylase may contribute to fitness in the mouse model of ascending UTI. Female CBA/J mice were infected by transurethral inoculation of 107 CFU of a 1:1 mixture of P. mirabilis HI4320 and the speA mutant (Fig.5). By the Wilcoxon signed rank test, the speA mutant was significantly outcompeted by P. mirabilis Hi4320 in the urine, bladder, and kidneys 7 days postinoculation (Fig.5A). To determine whether the fitness contribution of speA is strictly related to a role for putrescine biosynthesis during infection, a separate group of mice were infected with a 1:1 mixture of P. mirabilis HI4320 and the speBF double mutant, which is defective in both known pathways for putrescine biosynthesis but retains functional speA. Notably, the speBF double mutant did not exhibit a severe fitness defect and was only outcompeted by the parental strain in the urine (Fig.5B). The fitness data therefore suggest that speA may provide a greater fitness advantage than the contribution of putrescine biosynthesis alone. We thus conclude that maintenance of ΔpH and μH+ via arginine decarboxylase contributes to P. mirabilis fitness during experimental UTI.

Figure 5.

Arginine decarboxylase contributes to fitness in a mouse model of ascending UTI. CBA/J mice were infected by transurethral inoculation of a 1:1 mixture of Proteus mirabilis HI4320 and the speA mutant (A) or the speBF mutant (B). Urine (U), bladder (B), and kidneys (K) were collected 7 days postinoculation, and the ratio of mutant CFU mL−1 to wild-type CFU mL−1 recovered from each organ was determined and expressed as a competitive index (see Experimental Procedures). Dashed line indicates CI = 1. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 by the Wilcoxon signed rank test.

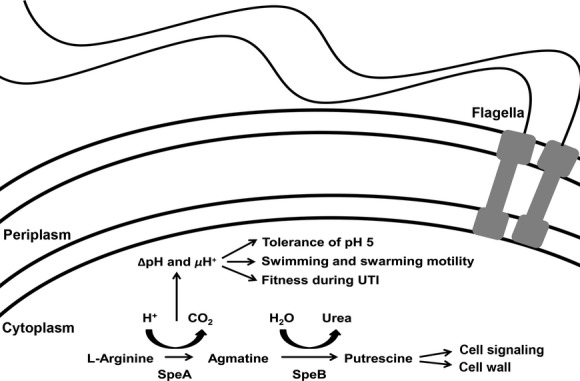

Proposed model of the contribution of arginine decarboxylase to P. mirabilis motility and fitness

A graphical summary of our results is shown in Figure6. Putrescine biosynthesis is known to be important for P. mirabilis swarming motility as the putrescine may act as a signaling molecule for coordination of swarming (Sturgill and Rather 2004; Kurihara et al. 2013), and putrescine is also a component of the core region of P. mirabilis lipopolysaccharide (Vinogradov and Perry 2000) and may be important for changes in cell wall composition during swarm cell differentiation. However, our results indicate that the arginine decarboxylase reaction has a separate contribution to motility and fitness beyond the role of this enzyme in putrescine biosynthesis. Arginine decarboxylase (SpeA) consumes a cytoplasmic proton to produce agmatine, thereby contributing to ΔpH and μH+. Conservation of ΔpH and μH+ contributes to tolerance of mildly acidic conditions and provides fuel for flagellar-mediated motility, such as swimming and swarming. As urine is mildly acidic and flagellar-mediated motility is important for ascension from the bladder to the kidneys during UTI, both of these factors likely contribute to fitness during UTI and the observed fitness defect of the speA mutant.

Figure 6.

Diagram of the contribution of arginine decarboxylase to motility and fitness. Our results indicate that the arginine decarboxylase reaction has a separate contribution to motility and fitness beyond the role of this enzyme in putrescine biosynthesis and the known contributions of putrescine to swarming motility. Arginine decarboxylase (SpeA) consumes a cytoplasmic proton to produce agmatine, thereby contributing to ΔpH and μH+. Conservation of ΔpH and μH+ contributes to tolerance of mildly acidic conditions and provides fuel for flagellar-mediated motility, such as swimming and swarming, while also contributing to fitness in a mouse model of ascending UTI.

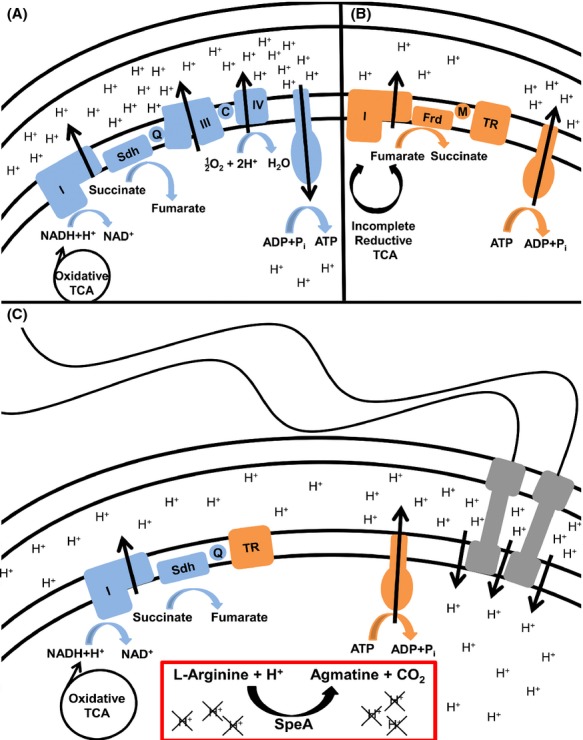

Despite being less energetically favorable than aerobic respiration, P. mirabilis appears to utilize an anaerobic respiratory chain during swarming (Armitage 1981; Falkinham and Hoffman 1984; Alteri et al. 2012), which would make it difficult to maintain μH+ and drive the rotation of hundreds to thousands of flagella (Fig.7). Our results concerning the contribution of arginine decarboxylase to conservation of μH+ indicate that P. mirabilis possesses additional mechanisms to fuel swarming under these unusual metabolic conditions, such as the use of l-arginine and SpeA to consume cytoplasmic protons.

Figure 7.

Model of μH+ generation and maintenance during swarming. Mechanisms for generating and maintaining μH+ are diagramed for aerobic conditions (A, blue), anaerobic conditions (B, orange), and the unusual system used during Proteus mirabilis swarming (C). (A) Under aerobic conditions, NADH is generated from pyruvate through a complete oxidative TCA cycle. Protons are pumped via a respiratory chain composed of NADH dehydrogenase (I), succinate dehydrogenase (Sdh), ubiquinone (Q), the cytochrome bc complex (III), cytochrome c (C), and cytochrome c oxidase (IV). A large proton gradient (ΔpH) is established and can be used to generate ATP. (B) When oxygen is not available, a branched TCA cycle is used and NADH will not be produced. The P. mirabilis anaerobic respiratory chain is likely composed of an alternative dehydrogenase (I), fumarate dehydrogenase (Frd), menaquinone (M), and a terminal reductase (TR). μH+ can be maintained by hydrolyzing the ATP produced through fermentation to pump protons across the membrane. This process is less energetically favorable and produces a weak ΔpH and μH+. (C) During swarming, P. mirabilis operates a complete oxidative TCA cycle and generates NADH, but oxygen is not used as the terminal electron acceptor. The swarming respiratory chain appears to be composed of NADH dehydrogenase (I), succinate dehydrogenase (Sdh), ubiquinone (Q), and an unknown terminal reductase (TR), possibly fumarate. ATP is most likely hydrolyzed to pump protons as the ATPase would otherwise be competing with the numerous flagella for ΔpH. While this process produces a weaker pH gradient than aerobic respiration, arginine and SpeA can be utilized as one method for consuming intracellular protons to strengthen the ΔpH and μH+ while also producing agmatine that can be utilized for putrescine biosynthesis.

Discussion

Proteus mirabilis poses a significant challenge for hospitals and long-term care facilities due to its ability to quickly traverse catheters to reach the urinary tract (Stickler and Hughes 1999; Sabbuba et al. 2002; Jacobsen et al. 2008), urease-mediated alkalinization of urine leading to catheter encrustation and urolithiasis (Griffith et al. 1976; Jones et al. 1990), and persistence within the urinary tract despite catheter changes and antibiotic treatment (Warren et al. 1982; Kunin 1989; Rahav et al. 1994). This bacterium possesses numerous virulence factors that contribute to colonization and ascension of the urinary tract, including fimbriae and other adhesins, urease, hemolysin, IgA protease, siderophores and metal transport systems, and flagellum-mediated motility (Armbruster and Mobley 2012). There is also a growing appreciation for the contribution of basic metabolic processes to P. mirabilis virulence, including a stringent requirement for nitrogen assimilation (Pearson et al. 2011) and identification of genes involved in carbohydrate and amino acid metabolism by signature-tagged mutagenesis studies (Burall et al. 2004; Himpsl et al. 2008). While these systems are generally complex and interconnected, we have demonstrated the ability of a single amino acid to influence P. mirabilis motility and fitness.

In this study, we have described a role of arginine decarboxylase (SpeA) in conservation of proton motive force (μH+) and fitness that can be at least partially separated from the critical role of putrescine during swarming. However, it is important to note that our results do not exclude a role for putrescine in coordination of swarming (Sturgill and Rather 2004; Kurihara et al. 2013). Even though SpeA was determined to be required for swimming motility and contributes to μH+, the swarming defect of the speA mutant can still be complemented by exogenous agmatine or putrescine. This finding indicates that putrescine is more important in the hierarchy of swarm signals than the μH+ contribution of SpeA on SWA. However, the contribution of SpeA to μH+ must be substantial for the speA mutant to have such a severe defect in swimming motility that was not observed for the speB mutant. We have clearly demonstrated that speA contributes to arginine-dependent alleviation of the effects of CCCP during incubation at pH 5, during swimming motility, and during swarming, while speB does not significantly impact response to arginine under any of these conditions. The results of the animal studies also indicate that SpeA provides a greater contribution to fitness during experimental UTI than putrescine biosynthesis alone. However, our data also do not exclude a role for putrescine during infection. Wild-type P. mirabilis upregulates putrescine importers during experimental UTI (Pearson et al. 2011), so the speBF double mutant likely procures putrescine from the host if needed.

The contribution of arginine to μH+ and motility is notable as it represents one possible explanation for the ability of P. mirabilis to fuel motility despite the unusual energetics of swarming. Proteus mirabilis swarm cells are thought to be entirely devoted to flagellar-mediated motility (Armitage 1981; Pearson et al. 2010), yet they appear to utilize energy pathways that do not require aerobic cytochromes and instead involve anaerobic electron transport chain components that would not be as energetically favorable as aerobic respiration (Alteri et al. 2012). Thus, P. mirabilis must have adapted alternate pathways to support the magnitude of μH+ required to fuel the hundreds to thousands of flagellar motors on a swarm cell. We propose that arginine decarboxylation is one such pathway, contributing to ΔpH and μH+ during swarming through the consumption of cytoplasmic protons, as shown in Figure7. It is, however, important to note that other mechanisms for conservation of μH+ during swarming are also likely utilized by P. mirabilis, and there may be additional mechanisms by which arginine affects μH+ and motility as the speA mutant was affected by arginine to some extent in all experiments.

There is a growing appreciation for the contribution of basic physiological processes to bacterial pathogenicity, and our findings clearly demonstrate that a single amino acid can have pleiotropic effects that contribute to fitness. For instance, the addition of 0.1 mmol/L arginine to agar plates made from pooled human urine is sufficient to promote extensive swarming (Armbruster et al. 2013), and the current study underscores the importance of arginine for both forms of flagellar-mediated motility as well as fitness during infection. The concentration of arginine in normal human urine is ∼0.01–0.2 mmol/L (Ren and Yan 2012; Liu et al. 2013), so P. mirabilis may use arginine decarboxylase as one mechanism to promote motility on urine-bathed catheters or within the host urinary tract. Considering the contribution of speA to fitness in the mouse model of ascending UTI, arginine decarboxylation may represent a new target for prevention of P. mirabilis swarming on catheters or possibly for therapeutic intervention during infection. In conclusion, our findings indicate that P. mirabilis has co-opted pathways outside of the respiratory chain to conserve the proton gradient (ΔpH) and μH+ in order to support motility and fitness.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge helpful comments and critiques from the members of the Mobley laboratory, especially Alejandra Yep. This research was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R01AI059722 (H. L. T. M.) and F32AI102552 (C. E. A.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Figure S1. Arginine decarboxylase is required for optimal growth at pH 5 and response to arginine. Proteus mirabilis HI4320 (A) and the speA mutant (B) were diluted 1:100 in unbuffered LB (pH 7) versus LB adjusted to pH 5 with or without 10 mmol/L arginine. Cultures were incubated at 37°C with continuous shaking, and OD600 readings were taken every 15 min for 18 h. Error bars indicate mean ± SD for one representative experiment with five replicates.

Table S1. Primers used in this study.

References

- Alteri CJ, Himpsl SD, Engstrom MD. Mobley HL. Anaerobic respiration using a complete oxidative TCA cycle drives multicellular swarming in Proteus mirabilis. MBio. 2012;3:e00365–12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00365-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster CE. Mobley HLT. Merging mythology and morphology: the multifaceted lifestyle of Proteus mirabilis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012;10:743–754. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster CE, Hodges SA. Mobley HL. Initiation of swarming motility by Proteus mirabilis occurs in response to specific cues present in urine and requires excess L-glutamine. J. Bacteriol. 2013;195:1305–1319. doi: 10.1128/JB.02136-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage JP. Changes in metabolic activity of Proteus mirabilis during swarming. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1981;125:445–450. doi: 10.1099/00221287-125-2-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belas R, Schneider R. Melch M. Characterization of Proteus mirabilis precocious swarming mutants: identification of rsba, encoding a regulator of swarming behavior. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:6126–6139. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6126-6139.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burall LS, Harro JM, Li X, Lockatell CV, Himpsl SD, Hebel JR, et al. Proteus mirabilis genes that contribute to pathogenesis of urinary tract infection: identification of 25 signature-tagged mutants attenuated at least 100-fold. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:2922–2938. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.5.2922-2938.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker C, Poore CA, Li X. Mobley HLT. Pathogenesis of Proteus mirabilis urinary tract infection. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:1497–1505. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)01304-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkinham JO., III Hoffman PS. Unique developmental characteristics of the swarm and short cells of Proteus vulgaris and Proteus mirabilis. J. Bacteriol. 1984;158:1037–1040. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.3.1037-1040.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster JW. Escherichia coli acid resistance: tales of an amateur acidophile. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004;2:898–907. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxman B. The epidemiology of urinary tract infection. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2010;7:653–660. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxman B. Brown P. Epidemiology of urinary tract infections: transmission and risk factors, incidence, and costs. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 2003;17:227–241. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(03)00005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabel CV. Berg HC. The speed of the flagellar rotary motor of Escherichia coli varies linearly with proton motive force. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:8748–8751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533395100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong S, Richard H. Foster JW. YjdE (AdiC) is the arginine:agmatine antiporter essential for arginine-dependent acid resistance in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:4402–4409. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.15.4402-4409.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith DP, Musher DM. Itin C. Urease. The primary cause of infection-induced urinary stones. Invest. Urol. 1976;13:346–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagberg L, Engberg I, Freter R, Lam J, Olling S. Svanborg Eden C. Ascending, unobstructed urinary tract infection in mice caused by pyelonephritogenic Escherichia coli of human origin. Infect. Immun. 1983;40:273–283. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.1.273-283.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himpsl SD, Lockatell CV, Hebel JR, Johnson DE. Mobley HLT. Identification of virulence determinants in uropathogenic Proteus mirabilis using signature-tagged mutagenesis. J. Med. Microbiol. 2008;57:1068–1078. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.2008/002071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooton TM, Bradley SF, Cardenas DD, Colgan R, Geerlings SE, Rice JC, et al. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 International Clinical Practice Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010;50:625–663. doi: 10.1086/650482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen SM, Stickler DJ, Mobley HLT. Shirtliff ME. Complicated catheter-associated urinary tract infections due to Escherichia coli and Proteus mirabilis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2008;21:26–59. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00019-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DE, Lockatell CV, Hall-Craigs M, Mobley HL. Warren JW. Uropathogenicity in rats and mice of Providencia stuartii from long-term catheterized patients. J. Urol. 1987;138:632–635. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)43287-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BD, Lockatell CV, Johnson DE, Warren JW. Mobley HL. Construction of a urease-negative mutant of Proteus mirabilis: analysis of virulence in a mouse model of ascending urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 1990;58:1120–1123. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.4.1120-1123.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klevens RM, Edwards JR, Richards CL, Jr, Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Pollock DA, et al. Estimating health care-associated infections and deaths in U.S. hospitals, 2002. Public Health Rep. 2007;122:160–166. doi: 10.1177/003335490712200205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunin CM. Blockage of urinary catheters: role of microorganisms and constituents of the urine on formation of encrustations. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1989;42:835–842. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(89)90096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara S, Sakai Y, Suzuki H, Muth A, Phanstiel O. Rather PN. Putrescine importer PlaP contributes to swarming motility and urothelial cell invasion in Proteus mirabilis. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:15668–15676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.454090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R, Li Q, Ma R, Lin X, Xu H. Bi K. Determination of polyamine metabolome in plasma and urine by ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method: application to identify potential markers for human hepatic cancer. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2013;791:36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2013.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobley HLT. Warren JW. Urease-positive bacteriuria and obstruction of long-term urinary catheters. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1987;25:2216–2217. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.11.2216-2217.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstein RM, Szostek B. Rather PN. Regulation of gene expression during swarmer cell differentiation in Proteus mirabilis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2010;34:753–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris NS, Stickler DJ. McLean RJ. The development of bacterial biofilms on indwelling urethral catheters. World J. Urol. 1999;17:345–350. doi: 10.1007/s003450050159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolle LE. Catheter-related urinary tract infection. Drugs Aging. 2005;22:627–639. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200522080-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara CM, Brenner FW. Miller JM. Classification, identification, and clinical significance of Proteus, Providencia, and Morganella. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2000;13:534–546. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.4.534-546.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson MM. Mobley HLT. The type III secretion system of Proteus mirabilis HI4320 does not contribute to virulence in the mouse model of ascending urinary tract infection. J. Med. Microbiol. 2007;56:1277–1283. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47314-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson MM, Sebaihia M, Churcher C, Quail MA, Seshasayee AS, Luscombe NM, et al. Complete genome sequence of uropathogenic Proteus mirabilis, a master of both adherence and motility. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:4027–4037. doi: 10.1128/JB.01981-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson MM, Rasko DA, Smith SN. Mobley HLT. Transcriptome of swarming Proteus mirabilis. Infect. Immun. 2010;78:2834–2845. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01222-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson MM, Yep A, Smith SN. Mobley HLT. Transcriptome of Proteus mirabilis in the murine urinary tract: virulence and nitrogen assimilation gene expression. Infect. Immun. 2011;79:2619–31. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05152-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahav G, Pinco E, Silbaq F. Bercovier H. Molecular epidemiology of catheter-associated bacteriuria in nursing home patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1994;32:1031–1034. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.4.1031-1034.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rather PN. Swarmer cell differentiation in Proteus mirabilis. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;7:1065–1073. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren HB. Yan XP. Ultrasonic assisted synthesis of adenosine triphosphate capped manganese-doped ZnS quantum dots for selective room temperature phosphorescence detection of arginine and methylated arginine in urine based on supramolecular Mg(2+)-adenosine triphosphate-arginine ternary system. Talanta. 2012;97:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2012.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbuba N, Hughes G. Stickler DJ. The migration of Proteus mirabilis and other urinary tract pathogens over Foley catheters. BJU Int. 2002;89:55–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-4096.2001.01721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider R, Lockatell CV, Johnson D. Belas R. Detection and mutation of a luxS-encoded autoinducer in Proteus mirabilis. Microbiology. 2002;148:773–782. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-3-773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims PJ, Waggoner AS, Wang CH. Hoffman JF. Studies on the mechanism by which cyanine dyes measure membrane potential in red blood cells and phosphatidylcholine vesicles. Biochemistry. 1974;13:3315–3330. doi: 10.1021/bi00713a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickler D. Hughes G. Ability of Proteus mirabilis to swarm over urethral catheters. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1999;18:206–208. doi: 10.1007/s100960050260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturgill G. Rather PN. Evidence that putrescine acts as an extracellular signal required for swarming in Proteus mirabilis. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;51:437–446. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuson HH, Copeland MF, Carey S, Sacotte R. Weibel DB. Flagellum density regulates Proteus mirabilis Swarmer cell motility in viscous environments. J. Bacteriol. 2013;195:368–377. doi: 10.1128/JB.01537-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradov E. Perry MB. Structural analysis of the core region of lipopolysaccharides from Proteus mirabilis serotypes O6, O48 and O57. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000;267:2439–2446. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren JW, Tenney JH, Hoopes JM, Muncie HL. Anthony WC. A prospective microbiologic study of bacteriuria in patients with chronic indwelling urethral catheters. J. Infect. Dis. 1982;146:719–723. doi: 10.1093/infdis/146.6.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Arginine decarboxylase is required for optimal growth at pH 5 and response to arginine. Proteus mirabilis HI4320 (A) and the speA mutant (B) were diluted 1:100 in unbuffered LB (pH 7) versus LB adjusted to pH 5 with or without 10 mmol/L arginine. Cultures were incubated at 37°C with continuous shaking, and OD600 readings were taken every 15 min for 18 h. Error bars indicate mean ± SD for one representative experiment with five replicates.

Table S1. Primers used in this study.