Significance

Why do humans cooperate in one-time interactions with strangers? The most prominent explanations for this long-standing puzzle rely on punishment of noncooperators, but differ in the form punishment takes. In models of direct punishment, noncooperators are punished directly at personal cost, whereas indirect reciprocity assumes that punishment is indirect by withholding rewards. To resolve the persistent debate on which model better explains cooperation, we conduct the first field experiment, to our knowledge, on direct and indirect punishment among strangers in real-life interactions. We show that many people punish noncooperators directly but prefer punishing indirectly by withholding help when possible. The occurrence of direct and indirect punishment in the field shows that both are key to understanding the evolution of human cooperation.

Keywords: cooperation, field experiment, indirect reciprocity, punishment, social norms

Abstract

Many interactions in modern human societies are among strangers. Explaining cooperation in such interactions is challenging. The two most prominent explanations critically depend on individuals’ willingness to punish defectors: In models of direct punishment, individuals punish antisocial behavior at a personal cost, whereas in models of indirect reciprocity, they punish indirectly by withholding rewards. We investigate these competing explanations in a field experiment with real-life interactions among strangers. We find clear evidence of both direct and indirect punishment. Direct punishment is not rewarded by strangers and, in line with models of indirect reciprocity, is crowded out by indirect punishment opportunities. The existence of direct and indirect punishment in daily life indicates the importance of both means for understanding the evolution of cooperation.

The extent of human cooperation is unique in the animal world (1). This is remarkable given that many interactions in large modern societies are one-shot encounters between strangers. Cooperation in these instances cannot be explained by the benefits that accrue from repeated encounters (1–5). The two most prominent explanations for cooperation in such instances both rely on individuals’ willingness to punish those who fail to cooperate (2, 3). The difference lies in the form punishment takes and its material consequences. The first mechanism involves the direct punishment of those behaving antisocially (6–11). Direct (or altruistic) punishment is individually costly, e.g., because it requires time and effort to enact, and the punisher bears the risk of retaliation when confronting a noncooperator (12–14). As a result, explaining how the propensity to punish directly may have evolved constitutes a major evolutionary puzzle (7, 15–20): “We seem to have replaced the problem of explaining cooperation with that of explaining [costly] punishment” (21).

In contrast to models of direct punishment, cooperation in models of indirect reciprocity is supported by the threat of indirect punishment (22–26): Individuals who come across others who are known to have behaved selfishly punish them by withholding reward (27–29). The key difference is that, unlike direct punishment, indirect punishment need not be costly as individuals may gain by withholding reward. Thus, explaining its evolution is less challenging. The ability to punish indirectly, however, raises the question of how instances of direct punishment may be explained (23). Why would individuals use direct costly punishment when they can withhold reward? The typical explanation is that direct punishers are rewarded by others who value the social norm and wish to maintain it: “In reality, … most punishment actions among humans are associated with the expectation of a delayed material gain” (23). Reward may take, for example, the form of a gift, positive feedback or an offer to help. This increases the punisher’s benefit from enforcing cooperation and may help offset the associated costs (4, 5, 24). In other words, direct punishment need not be costly in net terms for the punisher. However, there is little empirical evidence that strangers reward direct punishment (30, 31). If direct punishment is not rewarded in daily life, evolutionary forces will lead cooperators to use indirect punishment (23, 25).

For settling the debate on the importance of direct vs. indirect punishment for the evolution of cooperation among strangers, field experimental evidence from natural interactions is essential (2, 32, 33). From a theoretical perspective, the persistence of direct punishment is puzzling because it is assumed to be individually costly for the punisher, whereas this usually is not the case for indirect punishment. It is not obvious, however, that this holds true in daily life, in which direct punishment may be rewarded sufficiently (5, 23, 24) and in which indirect punishment by withholding reward also may involve substantial psychological or social costs (34, 35). Previous studies have explored direct punishment (9) and indirect reciprocity (36) in natural field settings, but in isolation from each other.

To our knowledge, this study presents the first evidence from a natural field experiment exploring the demand for direct and indirect punishment, separately and jointly. We address the following three questions: (i) Are punishers rewarded by strangers in one-shot interactions? (ii) Do individuals punish antisocial behavior indirectly by withholding reward? (iii) How is the propensity to punish directly affected by the opportunity to withhold reward? These questions are key to understanding how the propensity to punish selfish behavior may have evolved and, subsequently, the evolution of cooperation.

Testing Direct and Indirect Punishment in One-Shot Interactions in the Field

Our natural field experiment combines the advantages of the experimental approach with the advantages of studying behavior in a field environment. The experimental approach ensures that each observation is gathered under an identical script, allowing us to perform ceteris paribus comparisons. The advantage of the field environment is that it allows us to study the demand for direct and indirect punishment under their real costs and benefits without having to make any assumptions about them. Moreover, we can examine reactions to violations of an existing, widely known and well-established social norm (nonlittering). Finally, because our participants are observed in their natural environment and are unaware of participating in an experimental study, we avoid both demand and selection effects.

The experiment was run on various platforms in the two large international train stations in Cologne, Germany. The location is a major European intersection with more than 1,200 trains and 280,000 passengers a day, which implies that the probability interactions are not between strangers is minimal. In the experiment, a team of confederates simulated certain social interactions according to a fixed prespecified script and recorded the behavior of passengers who observed these interactions (henceforth, observers). Twelve confederates worked in groups of three. Each group consisted of two drama students, who enacted various scenarios depending on the treatments based on a prespecified script, and one supervisor, who collected data on the behavior of the observers. All confederates were unaware of the research hypotheses. Both actors were male in two of the groups, and both actors were female in the other two groups. In total, we collected 447 observations. Detailed notes on the experimental procedures are available in Supporting Information.

The four different treatments are summarized in Table 1. In treatment HelpPunisher, the interaction began with one of the confederates (called violator) noticeably dropping an empty coffee cup on the platform, thus violating the norm of not littering in public areas (Act 1: norm violation). After a few seconds, a second confederate (called punisher) approached the violator and said firmly but in a civil manner “Would you please pick up your garbage? The platform is not a garbage bin” (Act 2: punishment). The violator was instructed to always comply with this request calmly, pick up the cup without responding, and quietly leave the scene. Finally, the punisher reached for something inside her/his shoulder bag, dropping the entire content of seven books and booklets in front of an observer who had been standing alone near the scene (Act 3: needing help). This means that only one person (the observer) could help the punisher pick up the books. To answer our first research question (i.e., whether punishers of norm violators are rewarded) we compare helping rates in this treatment to the ones in BaseHelp—one of the two control treatments. In BaseHelp, we recorded helping rates in the absence of a norm violation or punishment. We say that an observer helped if s/he picked up at least one book or booklet. We say that direct punishment is rewarded if the helping rates are significantly higher in the HelpPun than in the BaseHelp treatment. See Supporting Information for pictures of the three acts.

Table 1.

Experimental treatments and description

| Act/Treatment | HelpPunisher | BaseHelp | HelpViolator | BasePun |

| Act 1: norm violation | Violator litters | — | Violator litters | Violator litters |

| Act 2: punishment | Punisher punishes | — | — | — |

| Act 3: needing help | Punisher drops books | Confederate drops books | Violator drops books | — |

| Dependent variable (observer’s behavior) | Helping | Helping | Direct punishment and helping | Direct punishment |

| N | 108 | 131 | 102 | 106 |

Treatment HelpViolator was identical to treatment HelpPunisher, except for the punishment act: After littering, the violator dropped the books in front of the observer. Hence, direct punishment by the observer (for instance by asking the violator to pick up the cup or expressing disapproval of the norm violation) and the observer’s offer to help are the measurable outcome variables. To address our second research question (i.e., whether individuals withhold rewards as a means of indirect punishment of norm violators) we compare helping rates in treatment HelpViolator with those in BaseHelp. If helping rates are significantly lower in the HelpViolator than in the BaseHelp treatment, we will have evidence that observers punish indirectly. Finally, we can answer our third research question regarding the interaction between direct and indirect punishment and the extent to which the former is crowded out by the latter by comparing direct punishment rates in HelpViolator with those in the second control treatment, BasePun. In BasePun, we measured the frequency with which violations of the nonlittering norm were punished by an observer standing alone near the scene of the violation. If direct punishment is less frequent in HelpViolator, in which indirect punishment opportunities exist, than in BasePun, we will have evidence that indirect punishment crowds out direct punishment.

To complement the field experiment, we conducted a survey study (see Supporting Information for details). We asked 232 different people in the same two train stations questions about their attitudes toward norm violators and norm enforcers in a hypothetical littering scenario that resembled the experimental situation.

Punishment of Norm Violators Is Not Rewarded

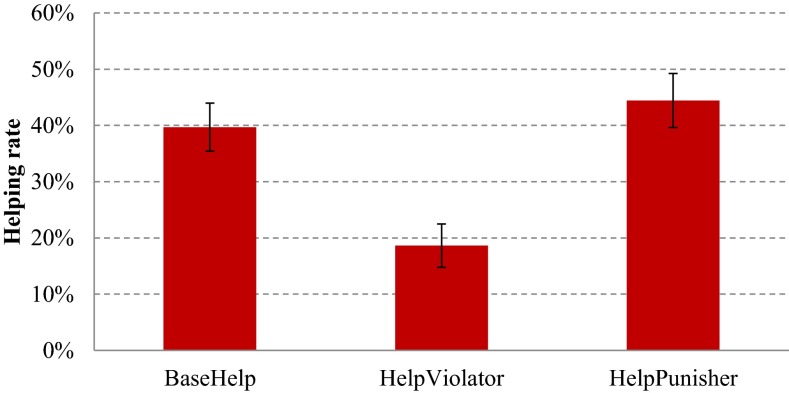

Fig. 1 shows that 39.7% of observers in the control treatment BaseHelp offered their help to the confederate who dropped the books in front of them. The rate of observers helping the punisher in treatment HelpPunisher is only slightly higher, 44.4%, and statistically indistinguishable from that in BaseHelp (N = 239, χ2 (1) = 0.55, P = 0.511, two-sided Fisher’s exact test). We also did not observe any other form of reward, such as kind words, friendly facial expressions, or gift giving, from the observer toward the punisher. Thus, there is no significant evidence of rewards for those who punish norm violators directly in one-shot interactions. The robustness of this finding is confirmed in a regression analysis controlling for a variety of observable characteristics (Supporting Information).

Fig. 1.

Helping rates by treatment. Help is offered more frequently in treatment BaseHelp than in HelpViolator, indicating that observers apply indirect punishment of norm violators by means of withholding help. Helping rates in HelpPunisher are not significantly different from treatment BaseHelp (i.e., no reward is given to punishers). Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. See main text for statistics.

Norm Violators Are Less Likely than Others to Receive Help

Compared with the control treatment BaseHelp, as can be seen in Fig. 1, the helping rate is substantially lower (18.6%) in treatment HelpViolator, in which the confederate in need of help had previously littered the train platform. The difference of 21.1 percentage points is significant (N = 233, χ2 (1) = 12.01, P = 0.001, two-sided Fisher’s exact test). Hence, our study provides clear field evidence of indirect punishment as a mechanism used to discipline norm violators and promote cooperation: Norm violators experience a much lower likelihood of receiving help from their social surroundings (see Supporting Information for supplementary regression analysis in support of this result). It also must be noted that if direct and indirect punishment are substitutes (29), the propensity to engage in indirect punishment may be even greater than in a setting without direct punishment opportunities.

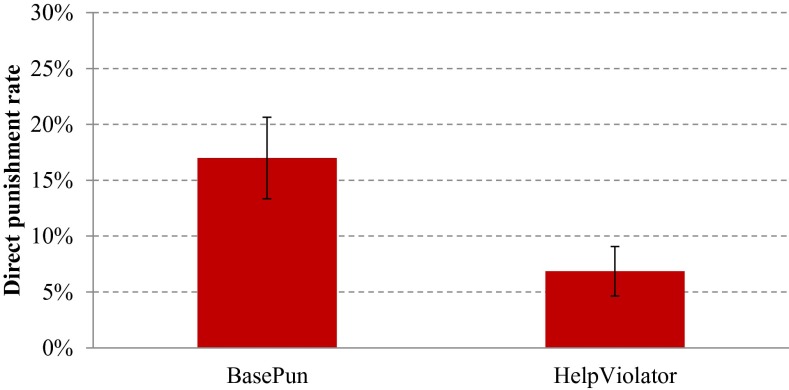

Indirect Punishment Opportunities Crowd out Direct Punishment

The direct punishment rates in the experiment are shown in Fig. 2. Recall that observers in the HelpViolator treatment may punish norm violators either directly by confronting the violator or indirectly by withholding their help. As can be seen, 17% of observers in BasePun punish violators directly. When observers are given the opportunity to withhold help in HelpViolator, the rate of direct punishment falls sharply to a mere 6.8%, which is significantly lower than in BasePun (N = 208, χ2 (1) = 5.03, P = 0.032, two-sided Fisher’s exact test). Combined with our finding that norm violators indeed are punished indirectly by means of withholding help in HelpViolator, the infrequent use of direct punishment in this treatment reveals that the existence of indirect punishment opportunities crowds out direct punishment. Therefore, in line with models of indirect reciprocity, in the absence of a reward for direct punishment, cooperators appear to prefer punishing indirectly by withholding help. At the same time, the crowding out is not complete, and a small minority of observers still use the costly mechanism of direct punishment.

Fig. 2.

Direct punishment rates by treatment. Direct punishment of norm violators is much more frequent in treatment BasePun than in treatment HelpViolator, in which observers also could punish indirectly. This is evidence that indirect punishment opportunities crowd out direct punishment. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. See main text for statistics.

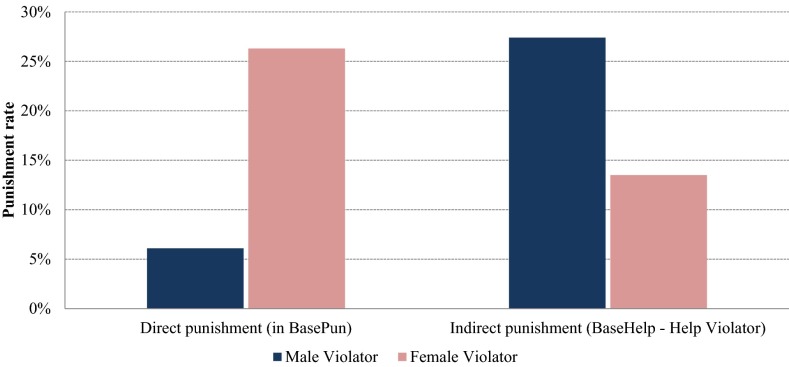

Direct Punishment Is Used Mostly Against Women, and Indirect Punishment Against Men

Our data reveal some interesting differences in the way men and women are punished for littering in public places. Fig. 3 reports the rates of direct and indirect punishment disaggregated by the sex of the violator. Indirect punishment is measured as the difference between mean helping rates in BaseHelp and in HelpViolator (i.e., as the extent to which help is withheld from violators of the social norm). A clear pattern emerges with respect to sex. Whereas women are more than four times as likely as men to be the target of direct punishment in BasePun [26.3% vs. 6.1%; N = 106, χ2 (1) = 7.62, P = 0.006, two-sided Fisher’s exact test], the reverse is true for indirect punishment: men are about twice as likely as women to be indirectly punished by withholding help in HelpViolator. The rates are 27.3% and 13.4%, respectively, and a χ2 test for the three-way interaction among helping rates, sex, and treatment (BaseHelp vs. HelpViolator) reveals a significant sex difference in indirect punishment (Poisson log-linear model, P = 0.050; see Supporting Information for details). This finding does not depend on the sex of the observer: both male and female observers are more likely to use direct punishment for female norm violators and indirect punishment for male norm violators.

Fig. 3.

Direct and indirect punishment by violator's sex. The first two bars on the left show that direct punishment is much more likely to be used against women (pink bar) than against men (blue bar). This pattern is reversed for indirect punishment, defined as the difference in helping rates between treatments BaseHelp and HelpViolator (third and fourth bars in the figure). This difference is larger for men (blue bar) than for women (pink bar). See main text for statistics.

Discussion

To our knowledge, our study provides the first evidence of the use of direct and indirect punishment, separately and jointly, in one-shot interactions in the field. We find clear evidence that direct punishment is not rewarded by third parties, suggesting it indeed is individually costly in net terms. This result seems particularly strong as our experiment was implemented under favorable conditions for the emergence of rewarding punishers. First, we ran the experiment using a population characterized by strong norms of civic cooperation (37). Indeed, the overwhelming majority of our survey respondents (96.1%) state they are bothered by littering, and 82.7% of them find the punishment of someone who litters a socially acceptable action. Second, the cost of helping was low in our experiment; observers had to help pick up only one book that had fallen in front them. Therefore, if punishment is rewarded in one-shot interactions, we would expect to find evidence of such behavior in our experiment. The absence of any rewards casts serious doubts on the common explanation that humans use direct punishment in one-shot interactions because they anticipate immediate social benefits.

In line with recent models of indirect reciprocity (23), we observe that indirect punishment opportunities strongly crowd out direct punishment. Given the absence of a reward for direct punishment and the fact that direct punishment likely is more costly in the field than in the laboratory because of the risk of retaliation, as evinced by several recent high-profile cases in which punishers were severely injured or even killed (38, 39), this seems reasonable. Indeed, fear of counterpunishment is the most common reason survey respondents give for not using direct punishment despite being bothered by littering (55% of responses). The fact that direct punishment is much more likely to be applied to female than male norm violators also points to this direction, if women are perceived as less likely to retaliate punishment or as less dangerous in the event of such retaliation. Indirect punishment opportunities, however, do not completely crowd out direct punishment. A small fraction of observers (6.8%) use direct punishment even when less costly means of punishment exist.

As with all experimental studies, more empirical evidence is needed to establish the extent to which our conclusions can be generalized. The norm violation in our experiment, for example, resembles free riding in public good experiments (6–8, 10–14, 40) as littering involves a negative externality shared by multiple individuals, including the punisher. Perhaps people will be willing to reward punishers if the violation affects a third party and not the punisher directly—as in third-party punishment experiments (28, 29, 41). It also will be interesting to investigate whether punishers are rewarded in repeated encounters (e.g., by friends, colleagues) and, if so, how this affects the extent to which indirect punishment crowds out direct punishment. In any case, the existence of direct and indirect punishment in our experiment indicates that both are important for understanding the evolution of cooperation.

Materials and Methods

All aspects of the study, including ethical acceptability, were reviewed by the Vice-Rectorate for Research at the University of Innsbruck, and permission was granted to conduct the experiment. The Deutsche Bahn also gave consent to running the experiment, which took place in May 2013 on various platforms in the two large (long-distance) train stations in Cologne, Germany. The data collection occurred between 9:00 AM and 5:00 PM. Four teams of three confederates each (two actors and one supervisor) simulated the social interactions outlined in Table 1 according to a precise prespecified script. To control for sex, both actors were male in two of the groups and both actors were female in the other two groups.

Acts were performed with single and standing observers only, to ensure there was no second-order public-good problem and that rewarding was costly for individuals who had to bend to pick up the books. Observers were randomly assigned into treatments. The supervisor recorded only acts in which the observer did not leave the scene and no other passenger approached. Moreover, the supervisor controlled that the various acts were performed correctly and that the observer witnessed the interaction in Acts 1 and 2 (Table 1), and recorded whether the observer helped pick up the books in Act 3 (in BaseHelp, HelpViolator, and HelpPunisher) and whether he or she applied direct punishment against the violator (in BasePun and HelpViolator).

Whenever an observer picked up at least one book, his or her action was recorded as help. Whenever an observer explicitly asked the violator to pick up the cup or expressed disapproval of the norm violation—for instance, by reprimanding the violator for his or her action—this was recorded as direct punishment. The supervisor also recorded the time of day the observation was collected and an estimate of the observer’s approximate age. After the interaction was completed, the team moved to a different platform.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the supervisors: Karen Heuermann, Vanessa Köneke, Anne Schielke, and Christopher Zeppenfeld; the actors: Tali Barde, Jens Jury, Dorina Leukhardt, Enver Mahaj, Christian Marchewka, Laura Schilz, Sarah Schneider, and Julia Schubeius; and Hendrik Beiler and Suparee Boonmanunt for conducting the questionnaire surveys. We thank Achim Zeileis for help with the statistical analysis and Anna Dreber, Ernst Fehr, Manfred Milinski, David Rand, Matthias Sutter, Marie Claire Villeval, and seminar participants in Georgetown University Qatar, New York University Abu Dhabi, Stockholm School of Economics, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, and Leicester University for comments. Financial support from the University of Innsbruck (Nachwuchsförderung W-140403) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1413170111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Fehr E, Fischbacher U. The nature of human altruism. Nature. 2003;425(6960):785–791. doi: 10.1038/nature02043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nowak MA. Evolving cooperation. J Theor Biol. 2012;299:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nowak MA. Five rules for the evolution of cooperation. Science. 2006;314(5805):1560–1563. doi: 10.1126/science.1133755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Axelrod R. An evolutionary approach to norms. Am Polit Sci Rev. 1986;80:1095–1111. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coleman J. Foundations of Social Theory. Harvard Univ Press; Cambridge, MA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fehr E, Gächter S. Cooperation and punishment in public goods experiments. Am Econ Rev. 2000;90:980–994. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fehr E, Gächter S. Altruistic punishment in humans. Nature. 2002;415(6868):137–140. doi: 10.1038/415137a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masclet D, Noussair C, Tucker S, Villeval M-C. Monetary and nonmonetary punishment in the voluntary contributions mechanism. Am Econ Rev. 2003;93:366–380. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balafoutas L, Nikiforakis N. Norm enforcement in the city: A natural field experiment. Eur Econ Rev. 2012;56:1773–1785. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gächter S, Renner E, Sefton M. The long-run benefits of punishment. Science. 2008;322(5907):1510. doi: 10.1126/science.1164744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gürerk O, Irlenbusch B, Rockenbach B. The competitive advantage of sanctioning institutions. Science. 2006;312(5770):108–111. doi: 10.1126/science.1123633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denant-Boemont L, Masclet D, Noussair C. Punishment, counterpunishment and sanction enforcement in a social dilemma experiment. Econ Theory. 2007;33:145–167. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nikiforakis N. Punishment and counter-punishment in public good games: Can we really govern ourselves? J Public Econ. 2008;92:91–112. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nikiforakis N, Engelmann D. Altruistic punishment and the threat of feuds. J Econ Behav Organ. 2011;78:319–332. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyd R, Gintis H, Bowles S, Richerson PJ. The evolution of altruistic punishment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(6):3531–3535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630443100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hauert C, Traulsen A, Brandt H, Nowak MA, Sigmund K. Via freedom to coercion: The emergence of costly punishment. Science. 2007;316(5833):1905–1907. doi: 10.1126/science.1141588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyd R, Gintis H, Bowles S. Coordinated punishment of defectors sustains cooperation and can proliferate when rare. Science. 2010;328(5978):617–620. doi: 10.1126/science.1183665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dreber A, Rand DG, Fudenberg D, Nowak MA. Winners don’t punish. Nature. 2008;452(7185):348–351. doi: 10.1038/nature06723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janssen MA, Bushman C. Evolution of cooperation and altruistic punishment when retaliation is possible. J Theor Biol. 2008;254(3):541–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rand DG, Armao JJ, 4th, Nakamaru M, Ohtsuki H. Anti-social punishment can prevent the co-evolution of punishment and cooperation. J Theor Biol. 2010;265(4):624–632. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colman A. The puzzle of cooperation. Nature. 2006;440:744. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nowak MA, Sigmund K. Evolution of indirect reciprocity. Nature. 2005;437(7063):1291–1298. doi: 10.1038/nature04131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohtsuki H, Iwasa Y, Nowak MA. Indirect reciprocity provides only a narrow margin of efficiency for costly punishment. Nature. 2009;457(7225):79–82. doi: 10.1038/nature07601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rockenbach B, Milinski M. To qualify as a social partner, humans hide severe punishment, although their observed cooperativeness is decisive. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(45):18307–18312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108996108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Panchanathan K, Boyd R. Indirect reciprocity can stabilize cooperation without the second-order free rider problem. Nature. 2004;432(7016):499–502. doi: 10.1038/nature02978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milinski M, Semmann D, Krambeck HJ. Reputation helps solve the ‘tragedy of the commons.’. Nature. 2002;415(6870):424–426. doi: 10.1038/415424a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rockenbach B, Milinski M. The efficient interaction of indirect reciprocity and costly punishment. Nature. 2006;444(7120):718–723. doi: 10.1038/nature05229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ule A, Schram A, Riedl A, Cason TN. Indirect punishment and generosity toward strangers. Science. 2009;326(5960):1701–1704. doi: 10.1126/science.1178883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nikiforakis N, Mitchell H. Mixing the carrots with the sticks: Third party punishment and reward. Exp Econ. 2014;17:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kiyonari T, Barclay P. Cooperation in social dilemmas: Free riding may be thwarted by second-order reward rather than by punishment. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;95(4):826–842. doi: 10.1037/a0011381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barclay P. Reputational benefits for altruistic punishment. Evol Hum Behav. 2006;27:325–344. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guala F. Reciprocity: Weak or strong? What punishment experiments do (and do not) demonstrate. Behav Brain Sci. 2012;35(1):1–15. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X11000069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sugden R. Altruistic punishment as an explanation of hunter-gatherer cooperation: How much has experimental economics achieved? Behav Brain Sci. 2012;35(1):40. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X11000902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adams GS, Mullen E. The social and psychological costs of punishing. Behav Brain Sci. 2012;35(1):15–16. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X11001142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van den Berg P, Molleman L, Weissing FJ. The social costs of punishment. Behav Brain Sci. 2012;35(1):42–43. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X11001348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoeli E, Hoffman M, Rand DG, Nowak MA. Powering up with indirect reciprocity in a large-scale field experiment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(Suppl 2):10424–10429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301210110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herrmann B, Thöni C, Gächter S. Antisocial punishment across societies. Science. 2008;319(5868):1362–1367. doi: 10.1126/science.1153808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edwards R. 2011 Police officers beaten by mob after asking girl to pick up litter. Available at www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/2433514/Police-officers-beaten-by-mob-after-asking-girl-to-pick-up-litter.html. Accessed September 1, 2014.

- 39. Spiegel Online International (2010) Murder on a station platform: German teenagers jailed for killing 'hero.' Available at www.spiegel.de/international/germany/murder-on-a-station-platform-german-teenagers-jailed-for-killing-hero-a-715963.html. Accessed September 1, 2014.

- 40.Rand DG, Dreber A, Ellingsen T, Fudenberg D, Nowak MA. Positive interactions promote public cooperation. Science. 2009;325(5945):1272–1275. doi: 10.1126/science.1177418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fehr E, Fischbacher U. Third-party punishment and social norms. Evol Hum Behav. 2004;25:63–87. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.