Abstract

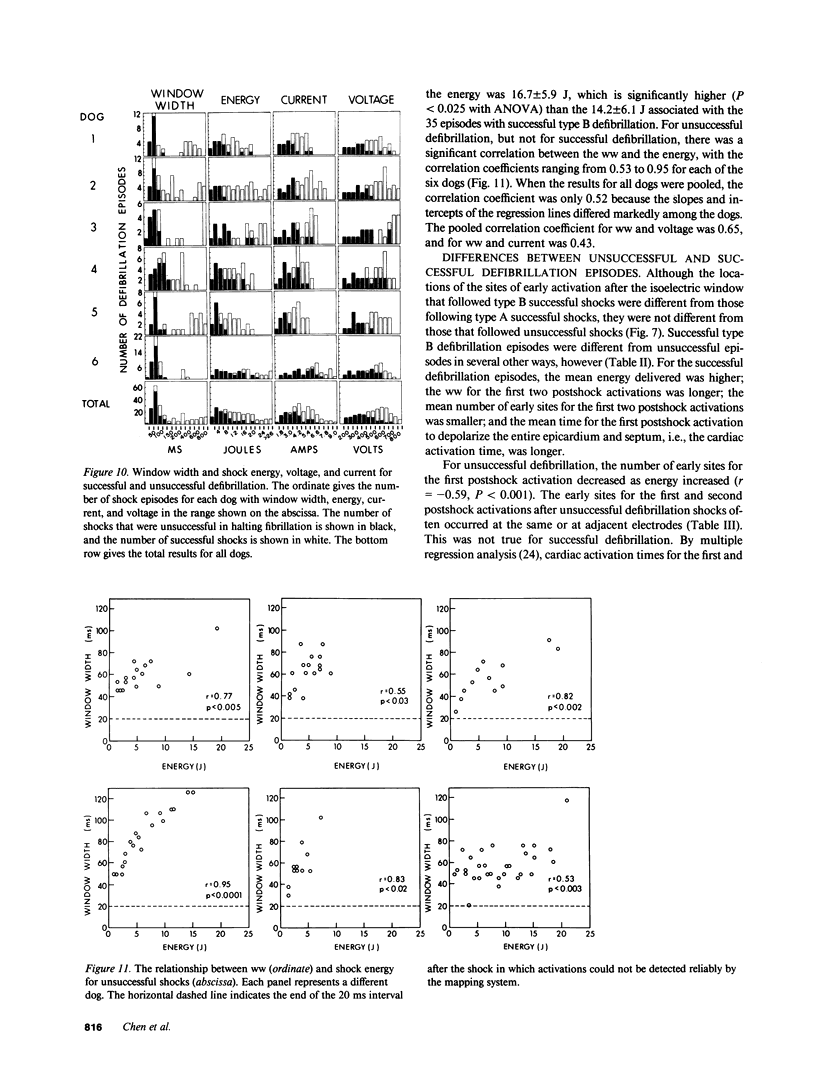

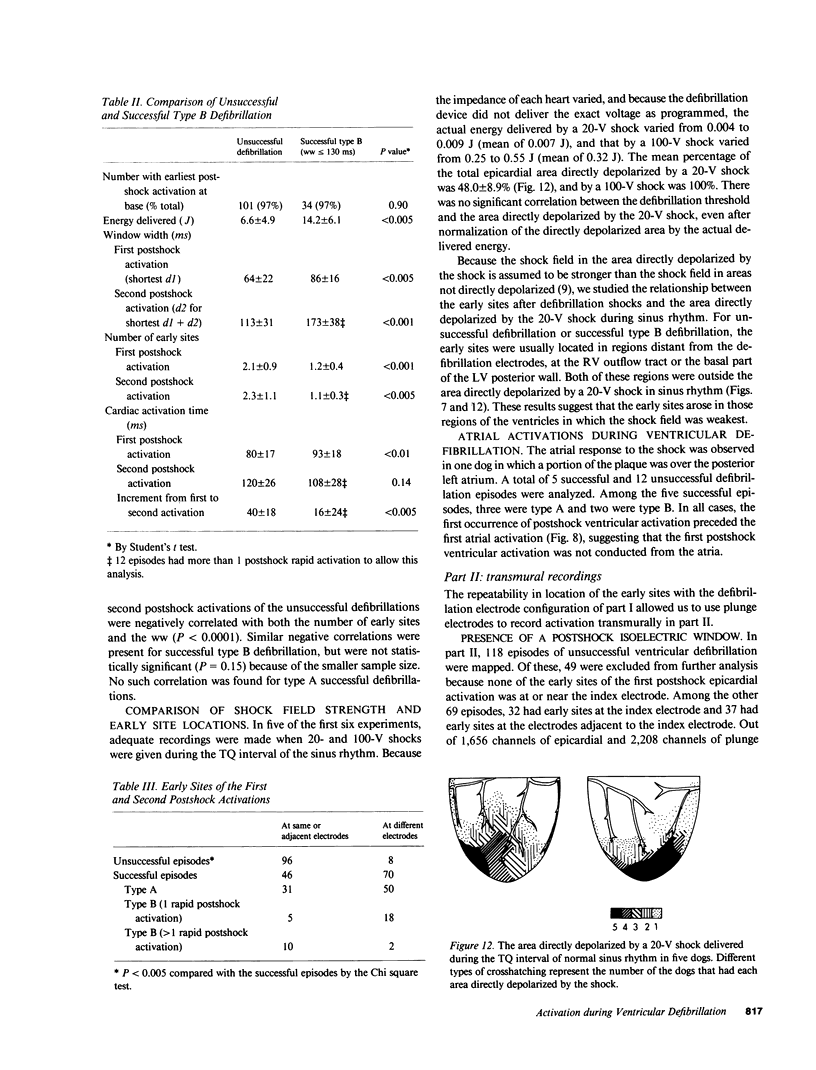

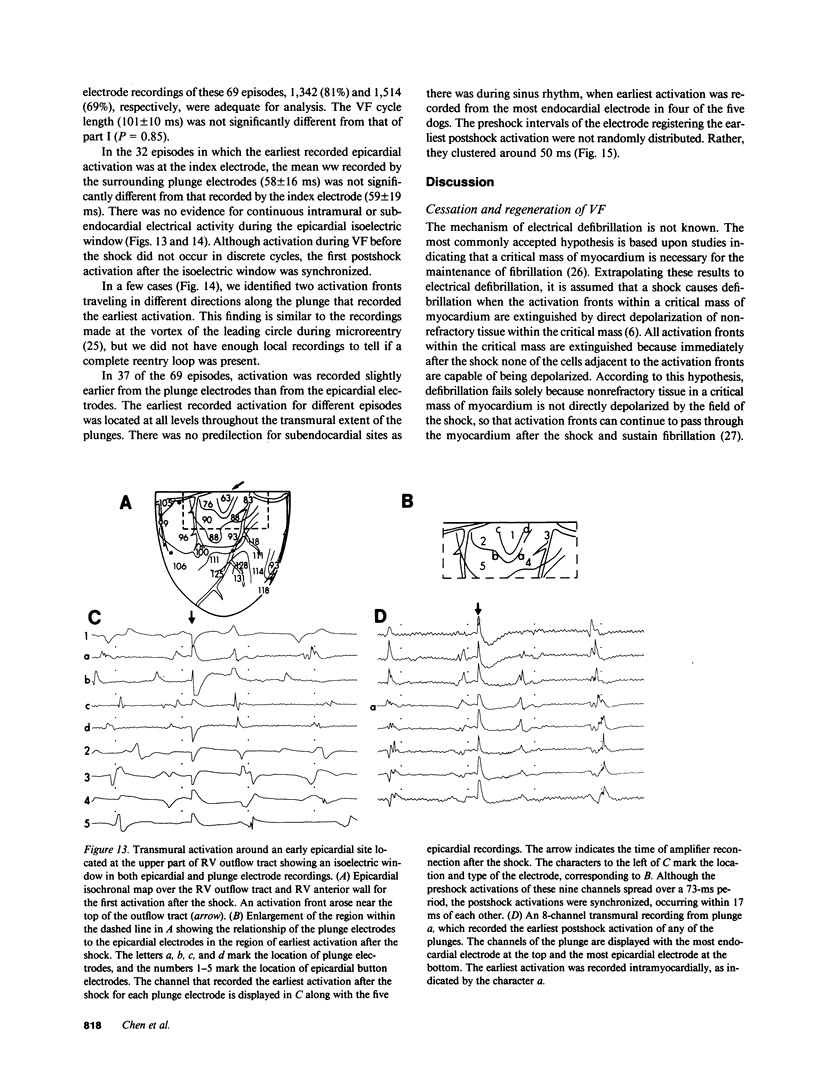

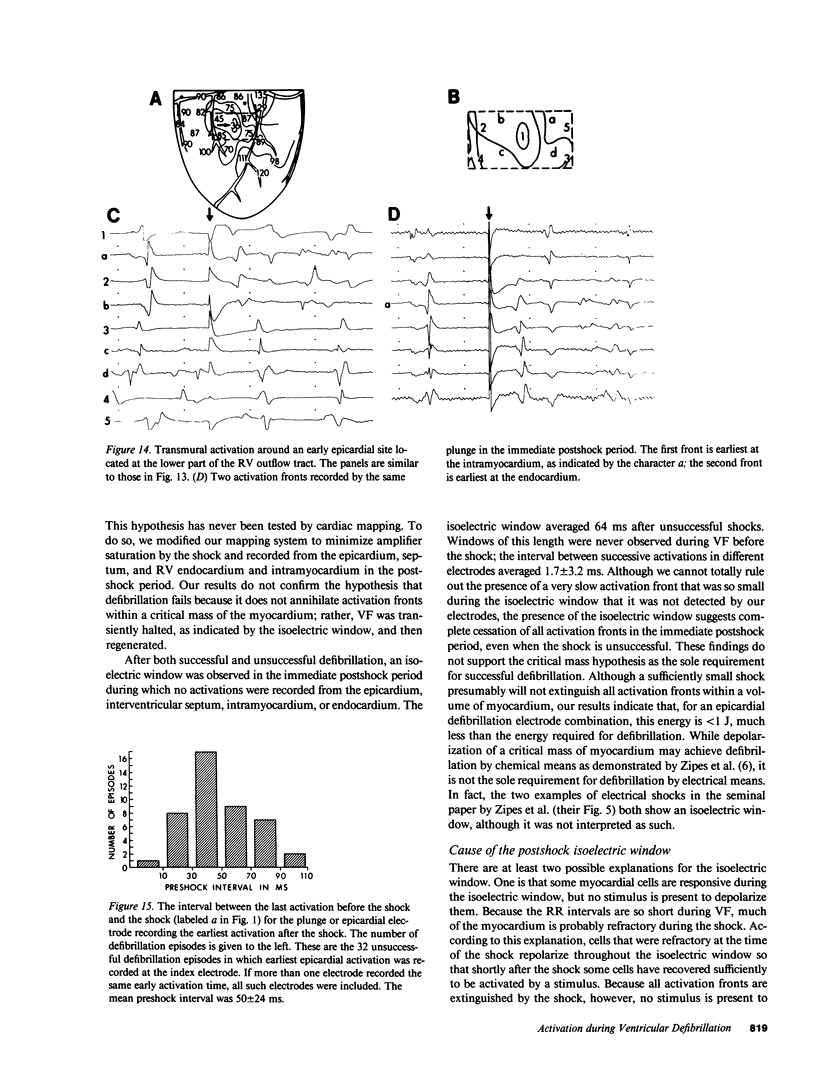

To test the hypothesis that a defibrillation shock is unsuccessful because it fails to annihilate activation fronts within a critical mass of myocardium, we recorded epicardial and transmural activation in 11 open-chest dogs during electrically induced ventricular fibrillation (VF). Shocks of 1-30 J were delivered through defibrillation electrodes on the left ventricular apex and right atrium. Simultaneous recordings were made from septal, intramural, and epicardial electrodes in various combinations. Immediately after all 104 unsuccessful and 116 successful defibrillation shocks, an isoelectric interval much longer than that observed during preshock VF occurred. During this time no epicardial, septal, or intramural activations were observed. This isoelectric window averaged 64 +/- 22 ms after unsuccessful defibrillation and 339 +/- 292 ms after successful defibrillation (P less than 0.02). After the isoelectric window of unsuccessful shocks, earliest activation was recorded from the base of the ventricles, which was the area farthest from the apical defibrillation electrode. Activation was synchronized for one or two cycles following unsuccessful shocks, after which VF regenerated. Thus, after both successful and unsuccessful defibrillation with epicardial shocks of greater than or equal to 1 J, an isoelectric window occurs during which no activation fronts are present; the postshock isoelectric window is shorter for unsuccessful than for successful defibrillation; unsuccessful shocks transiently synchronize activation before fibrillation regenerates; activation leading to the regeneration of VF after the isoelectric window for unsuccessful shocks originates in areas away from the defibrillation electrodes. The isoelectric window does not support the hypothesis that defibrillation fails solely because activation fronts are not halted within a critical mass of myocardium. Rather, unsuccessful epicardial shocks of greater than or equal to 1 J halt all activation fronts after which VF regenerates.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Allessie M. A., Bonke F. I., Schopman F. J. Circus movement in rabbit atrial muscle as a mechanism of tachycardia. III. The "leading circle" concept: a new model of circus movement in cardiac tissue without the involvement of an anatomical obstacle. Circ Res. 1977 Jul;41(1):9–18. doi: 10.1161/01.res.41.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amlie J. P., Owren T. The effect of prolonged pentobarbital anaesthesia on cardiac electrophysiology and inotropy of the dog heart in situ. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenh) 1979 Apr;44(4):264–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1979.tb02328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsdorf M. F. Membrane factors in arrhythmogenesis: concepts and definitions. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1977 May-Jun;19(6):413–429. doi: 10.1016/0033-0620(77)90008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babbs C. F. Effect of pentobarbital anesthesia on ventricular defibrillation threshold in dogs. Am Heart J. 1978 Mar;95(3):331–337. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(78)90364-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartram F. R., Ideker R. E., Smith W. M. A system for the parametric description of the ventricular surface of the heart. Comput Biomed Res. 1981 Dec;14(6):533–541. doi: 10.1016/0010-4809(81)90011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb F. R., Wallace A. G., Wagner G. S. Cardiac inotropic and coronary vascular responses to countershock. Circ Res. 1968 Dec;23(6):731–742. doi: 10.1161/01.res.23.6.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crampton R. Accepted, controversial, and speculative aspects of ventricular defibrillation. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1980 Nov-Dec;23(3):167–186. doi: 10.1016/0033-0620(80)90020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranefield P. F. Action potentials, afterpotentials, and arrhythmias. Circ Res. 1977 Oct;41(4):415–423. doi: 10.1161/01.res.41.4.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downar E., Janse M. J., Durrer D. The effect of acute coronary artery occlusion on subepicardial transmembrane potentials in the intact porcine heart. Circulation. 1977 Aug;56(2):217–224. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.56.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sherif N., Smith R. A., Evans K. Canine ventricular arrhythmias in the late myocardial infarction period. 8. Epicardial mapping of reentrant circuits. Circ Res. 1981 Jul;49(1):255–265. doi: 10.1161/01.res.49.1.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GALINDO A. H., DAVIS T. B. Succinylcholine and cardiac excitability. Anesthesiology. 1962 Jan-Feb;23:32–40. doi: 10.1097/00000542-196201000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geddes L. A., Tacker W. A., Rosborough J., Moore A. G., Cabler P., Bailey M., McCrady J. D., Witzel D. The electrical dose for ventricular defibrillation with electrodes applied directly to the heart. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1974 Oct;68(4):593–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin J. C., Mason J. W., Ross D. L., Calfee R. V. The treatment of ventricular tachycardia using an automatic tachycardia terminating pacemaker. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1981 Sep;4(5):582–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1981.tb06232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOFFMAN B. F., GORIN E. F., WAX F. S., SIEBENS A. A., BROOKS C. M. Vulnerability to fibrillation and the ventricular-excitability curve. Am J Physiol. 1951 Oct;167(1):88–94. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1951.167.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOFFMAN B., SUCKLING E. E., BROOKS C. M. Vulnerability of the dog ventricle and effects of defibrillation. Circ Res. 1955 Mar;3(2):147–151. doi: 10.1161/01.res.3.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison L., Ideker R. E., Smith W. M., Klein G. J., Kasell J., Wallace A. G., Gallagher J. J. The sock electrode array: a tool for determining global epicardial activation during unstable arrhythmias. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1980 Sep;3(5):531–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1980.tb05272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J. L., Jones R. E. Determination of safety factor for defibrillator waveforms in cultured heart cells. Am J Physiol. 1982 Apr;242(4):H662–H670. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1982.242.4.H662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephson M. E., Spielman S. R., Greenspan A. M., Horowitz L. N. Mechanism of ventricular fibrillation in man. Observations based on electrode catheter recordings. Am J Cardiol. 1979 Oct;44(4):623–631. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(79)90279-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOUWENHOVEN W. B., MILNOR W. R., KNICKERBOCKER G. G., CHESNUT W. R. Closed chest defibrillation of the heart. Surgery. 1957 Sep;42(3):550–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kralios F. A., Martin L., Burgess M. J., Millar K. Local ventricular repolarization changes due to sympathetic nerve-branch stimulation. Am J Physiol. 1975 May;228(5):1621–1626. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1975.228.5.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzara R., El-Sherif N., Hope R. R., Scherlag B. J. Ventricular arrhythmias and electrophysiological consequences of myocardial ischemia and infarction. Circ Res. 1978 Jun;42(6):740–749. doi: 10.1161/01.res.42.6.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepeschkin E., Jones J. L., Rush S., Jones R. E. Local potential gradients as a unifying measure for thresholds of stimulation, standstill, tachyarrhythmia and fibrillation appearing after strong capacitor discharges. Adv Cardiol. 1978;21:268–278. doi: 10.1159/000400463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lown B. Electrical reversion of cardiac arrhythmias. Br Heart J. 1967 Jul;29(4):469–489. doi: 10.1136/hrt.29.4.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins J. B., Zipes D. P. Effects of sympathetic and vagal nerves on recovery properties of the endocardium and epicardium of the canine left ventricle. Circ Res. 1980 Jan;46(1):100–110. doi: 10.1161/01.res.46.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowski M., Reid P. R., Mower M. M., Watkins L., Gott V. L., Schauble J. F., Langer A., Heilman M. S., Kolenik S. A., Fischell R. E. Termination of malignant ventricular arrhythmias with an implanted automatic defibrillator in human beings. N Engl J Med. 1980 Aug 7;303(6):322–324. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198008073030607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mower M. M., Mirowski M., Spear J. F., Moore E. N. Patterns of ventricular activity during catheter defibrillation. Circulation. 1974 May;49(5):858–861. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.49.5.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith W. M., Ideker R. E. Computer techniques for epicardial and endocardial mapping. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1983 Jul-Aug;26(1):15–32. doi: 10.1016/0033-0620(83)90016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN DAM R. T., DURRER D., STRACKEE J., VAN DER TWEEL L. H. The excitability cycle of the dog's left ventricle determined by anodal, cathodal, and bipolar stimulation. Circ Res. 1956 Mar;4(2):196–204. doi: 10.1161/01.res.4.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Vleet J. F., Tacker W. A., Jr, Geddes L. A., Ferrans V. J. Acute cardiac damage in dogs given multiple transthoracic shocks with a trapezoidal wave-form defibrillator. Am J Vet Res. 1977 May;38(5):617–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEST T. C., FREDERICKSON E. L., AMORY D. W. Single fiber recording of the ventricular response to induced hypothermia in the anesthetized dog: correlation with multicellular parameters. Circ Res. 1959 Nov;7:880–888. doi: 10.1161/01.res.7.6.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worley S. J., Swain J. L., Colavita P. G., Smith W. M., Ideker R. E. Development of an endocardial-epicardial gradient of activation rate during electrically induced, sustained ventricular fibrillation in dogs. Am J Cardiol. 1985 Mar 1;55(6):813–820. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(85)90162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipes D. P., Fischer J., King R. M., Nicoll A deB, Jolly W. W. Termination of ventricular fibrillation in dogs by depolarizing a critical amount of myocardium. Am J Cardiol. 1975 Jul;36(1):37–44. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(75)90865-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]