Abstract

Chondrogenesis is a developmental process that is controlled and coordinated by many growth and differentiation factors as well as environmental factors that initiate or suppress cellular signaling pathways and transcription of specific genes in a temporal-spatial manner. As key signaling molecules in regulating cell proliferation, homeostasis, and development, both mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) and the Wnt family participate in morphogenesis and tissue patterning and play important roles in skeletal development, especially chondrogenesis. Recent findings suggest that both signals are also actively involved in arthritis and related diseases. Despite the fact that the crosstalk between MAPK and Wnt signaling has been implicated to play a significant role in cancer, few studies have summarized this interaction and crosstalk in regulating chondrogenesis. In this review, we focus on MAPK and Wnt signaling in reference to their relationships in different types of cells and particularly how this crosstalk might influence chondrogenesis and cartilage development. We also discuss how the interactions between MAPK and Wnt signaling might relate to cartilage related diseases such as osteoarthritis and explore the potential therapeutic targets for disease treatments.

Keywords: Chondrogenesis, MAPK signal, Wnt signal, Stem cell, Osteoarthritis

Introduction

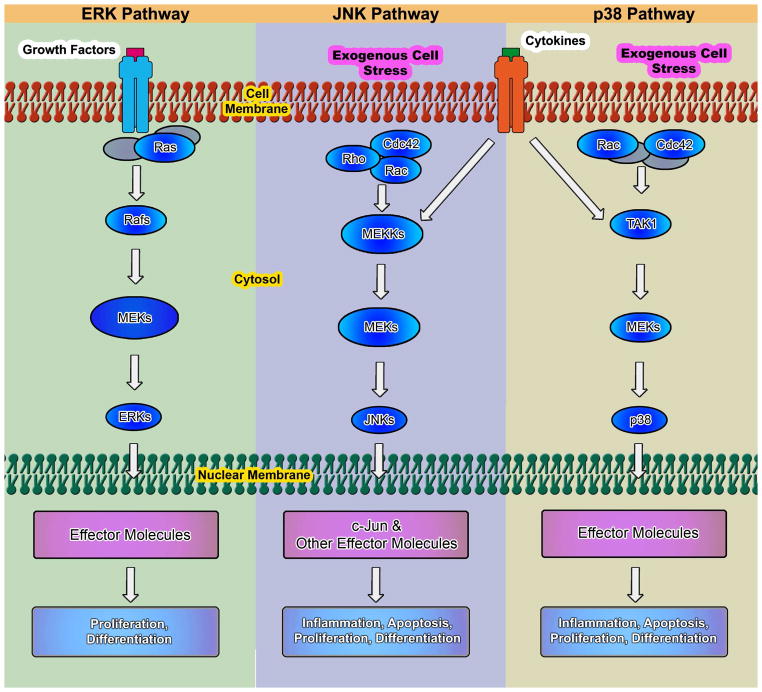

Chondrogenesis is a morphogenetic event that includes proliferation, condensation, and differentiation of mesenchymal cells into chondrocytes with the production of a cartilage-specific extracellular matrix (ECM) rich in type II collagen and sulfated proteoglycans (Cancedda et al. 2000). Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) is one of the conserved signal transduction systems in cartilage, which plays a crucial role in chondrogenic differentiation. The MAPK cascades constituting three sequentially activated kinase complexes, which include p38 MAPK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and extracellular regulated kinase (ERK), are substrates for phosphorylation by MAPK kinases (MKKs) (Fig. 1). The MKKs are in turn phosphorylated by MAPK kinase kinases (MEKKs). Regarding chondrogenesis and chondrocyte differentiation, ERK and p38 MAPK have central roles in mediating chondrocyte proliferation and related gene expression (Krens et al. 2006), whereas JNK has a minor role in chondrogenesis as JNK phosphorylation is not affected during the process (Nakamura et al. 1999; Stanton et al. 2003). p38 MAPK is usually phosphorylated during chondrogenesis and is generally accepted as a positive regulator in chondrogenesis and chondrocyte differentiation (Oh et al. 2000; Stanton et al. 2003; Watanabe et al. 2001); however, the role of the ERK MAPK pathway (also known as the MEK-ERK kinase cascade) is still controversial. Murakami et al. reported that ERK is a positive regulator in chondrogenesis, as the increase in SRY (sex determining region Y)-box 9 (SOX9) levels induced by basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF2) was inhibited by a specific ERK kinase (MEK) inhibitor (U0126) in primary chondrocytes. Co-expression of a constitutively active mutant of MEK1 increased the activity of the Sox9-dependent enhancer in primary chondrocytes and C3H10T1/2 cells (Murakami et al. 2000). However, some studies interpreted MEK-ERK as a negative factor for chondrogenesis. For example, ERK1/2 activities were observed to decrease as chondrogenesis proceeded and inhibition of ERK1/2 with PD98059 enhanced chondrogenesis (Oh et al. 2000); other studies also showed similar results (Bobick and Kulyk 2004; Chang et al. 1998).

Fig. 1.

The best characterized MAPK modules are the ERK pathway, the SAPK/JNK pathway, and the p38 MAPK pathway. The MAPK cascades consist of an MEKK, an MEK, and an MAPK. MEKKs are activated through a large variety of extracellular signals such as growth factors, cytokine factors, and stress. The activated MEKKs can phosphorylate and activate one or several MEKs, which, in turn, phosphorylate and activate a specific MAPK. Activated MAPK phosphorylates and activates various substrates in the cytoplasma and the nucleus of the cell, including transcription factors. These downstream targets control cellular responses (e.g., apoptosis, proliferation, and differentiation).

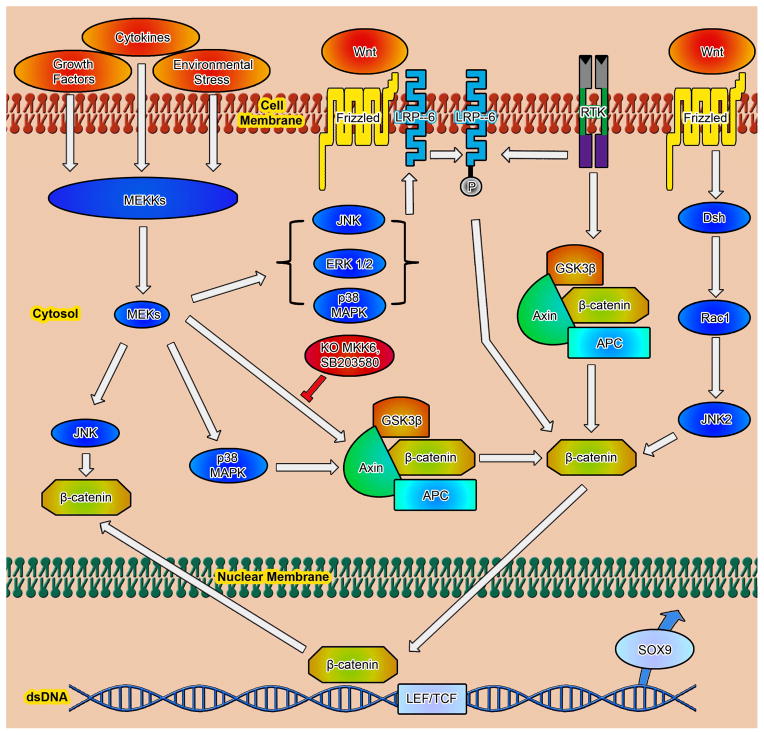

The Wnt family of secreted glycoproteins are signaling molecules that play important roles in controlling a wide range of developmental processes, including tissue patterning, cell proliferation, and cell fate, through two distinct signaling pathways, in terms of the canonical and non-canonical Wnt pathways (Fig. 2). In the canonical Wnt signaling pathway, binding of secreted Wnts to the Frizzled family of cell surface receptors inactivates glycogen synthase kinase 3beta (GSK3β), resulting in stabilization and nuclear translocation of β-catenin and activation of Wnt target genes. The non-canonical pathways also signal through the Frizzled receptors; the planar cell polarity (PCP) pathway activates the rho family of GTPases and JNK and modifies cytoskeletal organization and epithelial cell polarization. The Wnt/Ca2+ pathway stimulates the intracellular increase of Ca2+ through activation of protein kinase C (PKC) and calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII) (Akiyama et al. 2004). During embryonic skeletogenesis, Wnt components act as both positive and negative regulators of key events, including chondroblast differentiation, chondrocyte maturation, and joint formation (Church and Francis-West 2002).

Fig. 2.

Three Wnt-dependent pathways have been categorized: canonical Wnt/β-catenin and non-canonical Wnt/PCP as well as Wnt/Ca2+ pathways. Canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway: In cells, with an inactive state of canonical Wnt signaling, cytosolic β-catenin is targeted to proteolytic degradation through phosphorylation by the APC–Axin–GSK3β complex and further ubiquitination through action of βTrCP-dependent E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. On stimulation by Wnt ligands through binding to Fzd receptors and its co-receptor Lrp, Fzd recruits and phosphorates Dsh, and inhibits APC–Axin–GSK3β complex formation by the recruitment and inhibition of GSK3β. Consequently, β-catenin can accumulate in the cytoplasm and enter the nucleus, activating transcription of target genes through association with the Lef1/Tcf transcription factor family. Non-canonical Wnt/Ca2+ pathway: Interaction of Wnt ligands with Fzd receptors can lead to an increase in intracellular calcium level, through possibly the activation of phospholipase C (PLC). Intracellular calcium will subsequently activate Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CAMKII) and protein kinase C (PKC) in cells, as well as the transcription factor NFAT. This pathway is particularly important for convergent-extension movements during gastrulation. Additionally, Fzd receptors can also activate JNK, promoting expression of specific genes through activation of AP-1. Non-canonical Wnt/PCP pathway: This pathway is characterized by an asymmetric distribution of Fzd and related receptors, resulting in the polarization of the cell. Also, Wnt-signaling activates Cdc42, RhoA, and Rac1 leading to cytoskeleton rearrangement. Rac1 can also activate JNK, activating specific gene transcription through modulation of the AP-1 protein complex.

In embryos, low levels of Wnt/β-catenin signaling stimulate chondrogenic differentiation of stem cells whereas high levels of Wnt/β-catenin signaling inhibit that process (Hartmann 2006; Johnson and Rajamannan 2006; Westendorf et al. 2004). Wnts have also been shown to both inhibit and stimulate chondrogenic differentiation of adult progenitor cells (Day et al. 2005; Hill et al. 2005; Hu et al. 2005). Removal of β-catenin early in mesenchymal progenitor cells promoted chondrocyte differentiation while ectopic expression of an activated form of β-catenin in early differentiating chondrocytes induced ectopic joint formation both morphologically and molecularly (Guo et al. 2004). In adult progenitor cells, osteoblast precursors lacking β-catenin are blocked in differentiation and develop into chondrocytes instead. Detailed in vivo and in vitro loss-and gain-of-function analyses reveal that β-catenin activity is necessary and sufficient to repress the differentiation of mesenchymal cells into runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) and SOX9-positive skeletal precursors (Hill et al. 2005), suggesting that Wnt/β-catenin signaling controls osteoblast and chondrocyte formation when they differentiate from mesenchymal progenitors.

It has been reported that the MAPK pathway also regulates Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Wnt/β-catenin signaling was activated by LIT1 and MOM4, which separately encode a homologue of the MAPK-related Nemo-like Kinase (NLK) and a homologue of transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ)-activated kinase (TAK-1) (Meneghini et al. 1999). TAK-1, a MEKK activated by TGFβ, bone morphogenetic protein (BMP), and other MAPK signaling components, plays a critical role in chondrogenesis. Deletion of TAK1 in chondrocytes resulted in novel embryonic developmental cartilage defects including decreased chondrocyte proliferation, reduced proliferating chondrocyte survival, delayed onset of hypertrophy, and reduced matrix metalloproteinase-13 (MMP13) expression (Gunnell et al. 2010). Since both MAPK and Wnt signaling pathways play critical regulatory roles in the development of cartilage and bone formation, studying their interactions and crosstalk is of extreme importance to elucidate the complex signaling networks in chondrogenesis and to explore potential therapeutic targets for related diseases such as osteoarthritis (OA).

Influence of canonical Wnt signals on the MAPK pathway

In totipotent mouse F9 teratocarcinoma cells, the canonical Wnt-β-catenin-JNK signaling pathway was found to be activated by G-proteins, which can propagate the signals downstream through Dishevelled isoforms. Suppression of Dishevelled-1 or Dishevelled-3 abolished Wnt3a activation of JNK (Bikkavilli et al. 2008a). Wnt3a treatment enhanced the mRNA and protein expression of c-Jun and stimulated the phosphorylation of c-Jun and JNK. Furthermore, Wnt3a activation of activator protein-1 (AP-1) was blocked by the inhibition of JNK with SP600125 and by the inhibition of AP-1 with N-acetyl-L-cysteine and nordihydroguaiaretic acid (Hwang et al. 2005). AP-1 was also activated by ERK1/2 in C3H10T1/2 cells (Seghatoleslami et al. 2003). In NIH3T3 fibroblast cells, ERK pathway activation by Wnt signaling could occur at multiple levels, including β-catenin-independent direct signaling resulting from a Wnt3a (Wnt3a-Raf-1-MEK-ERK) and a β-catenin-/Tcf-4-dependent post gene transcription event (Yun et al. 2005). In addition to JNK and ERK, p38 MAPK was strongly activated by Wnt3a in mouse F9 teratocarcinoma cells and the activated p38 MAPK regulated canonical Wnt-β-catenin signaling through regulation of GSK3β. Chemical inhibitors of p38 MAPK (SB203580) and expression of a dominant negative-version of p38 MAPK attenuated Wnt3a-induced accumulation of β-catenin, Lef/Tcf-sensitive gene activation, and primitive endoderm formation (Bikkavilli et al. 2008b). The above evidence indicates the influence of canonical Wnt signals on the MAPK pathway (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Influence of canonical Wnt signals on the MAPK pathway. Wnt3a treatment activated the Raf-1-MEK-ERK cascade (Yun et al. 2005) and the JNK pathways (Bikkavilli et al. 2008a). Furthermore, Wnt3a activation of activator protein-1 (AP-1) was blocked by the inhibition of JNK with SP600125 and by the inhibition of AP-1 with N-acetyl-L-cysteine and nordihydroguaiaretic acid (Hwang et al. 2005). In C3H10T1/2 cells, AP-1 was activated by ERK1/2 (Seghatoleslami et al. 2003). In totipotent mouse F9 teratocarcinoma cells, canonical Wnt-β-catenin-JNK signaling was found to be activated by G-proteins, which propagated the signals downstream through Dishevelled (Dsh) isoforms; suppression of Dsh-1 or Dsh-3 abolished Wnt3a activation of JNK (Bikkavilli et al. 2008a). In addition to JNK and ERK, p38 MAPK was strongly activated by Wnt3a and the activated p38 MAPK regulated canonical Wnt-β-catenin signaling through regulation of GSK3β. Chemical inhibitors of p38 MAPK (SB203580) and expression of a dominant negative (DN)-version of p38 MAPK attenuated Wnt3a-induced accumulation of β-catenin, Lef/Tcf-sensitive gene activation, and primitive endoderm formation (Bikkavilli et al. 2008b).

It is known that reduced expression of adhesion molecules is associated with formation and differentiation of cartilage nodules, which is supported by the fact that N-cadherin is expressed in prechondrogenic mesenchymes during cell condensation but not in differentiated chondrocytes (Oberlender and Tuan 1994; Tavella et al. 1994). One study indicated that inhibition of p38 MAPK results in sustained expression of N-cadherin and eventually inhibits the chondrogenic differentiation in chick limb mesenchymal micromass cultures (Oh et al. 2000). Wnt regulation of limb mesenchymal chondrogenesis is also involved in the modulation of N-cadherin. Wnt7a signaling has been shown to inhibit chondrogenic differentiation of limb mesenchymal cells in vitro by modulating the expression of N-cadherin and the turnover of N-cadherin-dependent cell-cell adhesion complexes (Tufan and Tuan 2001). The combination of Wnt7a misexpression and ERK inhibition partially recovers Wnt7a inhibition of chondrogenic differentiation, whereas the combination of Wnt7a misexpression and p38 inhibition acts in a synergistic chondro-inhibitory fashion (Tufan et al. 2002).

Wnt3a can also induce a rapid and transient activation of p38 MAPK, which in turn regulates alkaline phosphatase activity and mineralization of nodules, directing the differentiation of mesenchymal cells into osteoprogenitors. Dickkopf1, a selective antagonist of Wnt proteins, did not influence the activation of p38 MAPK and ERK induced by Wnt3a (Caverzasio and Manen 2007), implying that non-canonical Wnt pathways might participate in the regulatory process of mesenchymal cell differentiation into osteogenic cells.

Influence of non-canonical Wnt signals on the MAPK pathway

As a non-canonical Wnt signal, Wnt5a specifically promotes entry into the prehypertrophic phase, whereas it conversely blocks chondrocyte hypertrophy, acting in a stage-specific context (Kawakami et al. 1999; Yang et al. 2003). This finding was confirmed by a study showing that Wnt5a misexpression delays the maturation of chondrocytes and the onset of bone collar formation (Hartmann and Tabin 2000). Wnt5a increased chondrocyte differentiation at an early stage through CaMK/calcineurin (CaN)/nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT)-dependent induction of Sox9 while repressing chondrocyte hypertrophy via IκB kinase (IKK)/nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB)-dependent inhibition of Runx2 expression (Bradley and Drissi 2010). In mouse F9 embryonal teratocarcinoma cells, a strong activation of p38 MAPK was observed in response to Wnt5a; treatment with SB203580 effectively abolished the stimulatory effects of Wnt5a (Ma and Wang 2007). Both exogenous TGFβ3 and overexpression of Wnt5a stimulated PKCα and p38 MAPK activation early in the culture, resulting in cellular condensation and chondrogenesis. Comparatively, inhibiting PKCα or p38 MAPK activity abolished the promotion of chondrogenic differentiation by overexpressing Wnt5a or exogenous TGFβ3. On the other hand, partial reduction of endogenous WNT5A by small interfering RNA diminished TGFβ3-stimulated chondrogenesis through inhibition of PKCα and p38 MAPK activity (Jin et al. 2006a). Wnt5a was also found to promote ERK1/2 phosphorylation in endothelial cells (Masckauchán et al. 2006); the expression of Wnt5a blocked canonical Wnt signaling in endothelial cells and other cell types (Topol et al. 2003). (Fig. 4)

Fig. 4.

Influence of non-canonical Wnt signals on the MAPK pathway. In mouse F9 teratocarcinoma embryonal cells, a strong activation of p38 MAPK was observed in response to Wnt5a and treatment with SB203580 effectively abolished the ability of Wnt5a’s stimulatory effects (Ma and Wang 2007). Wnt5a was also found to promote ERK1/2 phosphorylation, enhancing endothelial cell survival and proliferation (Masckauchán et al. 2006), and the expression of Wnt5a blocked canonical Wnt signaling in endothelial cells (Masckauchán et al. 2006) and other cell types (Topol et al. 2003). However, non-canonical Wnt signaling more commonly functions through the Wnt-JNK pathway. Activation of Wnt5a signaling by IL-1β induced the expression of MMPs via the JNK pathway in rabbit temporomandibular joint (TMJ) condylar chondrocytes, whereas blockage of JNK signaling impaired the Wnt5a-induced up-regulation of MMPs (Ge et al. 2009). Wnt5a increased chondrocyte differentiation at an early stage through CaMK/NFAT-dependent induction of Sox9 while repressing chondrocyte hypertrophy via NF-κB-dependent inhibition of Runx2 expression (Bradley and Drissi 2010). Wnt5b activated JNK, a component of the planar cell polarity pathway, contributed to an increase in cellular migration while Wnt5b also decreased cell-cell adhesion through an activation of Src and subsequent cadherin receptor turnover (Bradley and Drissi 2011).

However, non-canonical Wnt signaling more commonly functions through the Wnt-JNK pathways (Logan and Nusse 2004). Activation of Wnt5a signaling by interleukin 1beta (IL-1β) induced the expression of MMPs via the JNK pathways in rabbit temporomandibular joint (TMJ) condylar chondrocytes, whereas blockage of JNK signaling impaired the Wnt5a-induced up-regulation of MMPs (Ge et al. 2009). The highly homologous non-canonical Wnt signals, Wnt5a and Wnt5b, have differential effects on cartilage development in regard to cell proliferation and expression of type II collagen. Unlike Wnt5a, Wnt5b repressed chondrocyte differentiation in both the initial stages of cartilage condensation and the late hypertrophic stage (Yang et al. 2003). Wnt5b activated JNK, a component of the PCP pathway, contributing to an increase in cellular migration and Wnt5b-mediated decreases in cell-cell adhesion through an activation of Src and subsequent cadherin receptor turnover (Bradley and Drissi 2011). (Fig. 4)

Wnt5a also plays an important role in osteoblast differentiation. The MAPK pathway was altered in Wnt5a-deficient mouse calvarial cells, suggesting that Wnt5a signaling influenced the MAPK/JNK pathway (Guo et al. 2008). Other studies provide evidence for crosstalk between Wnt5a and MAPK. Ishitani et al. found that overexpression of Wnt5a in HEK293 cells activated NLK MAPK through TAK-1; furthermore, overexpression of Wnt5a antagonized the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway (Ishitani et al. 2003). Through CaMKII-TAK1-TAB2-NLK, non-canonical Wnt signaling transcriptionally repressed peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARG) transactivation and induced RUNX2 expression, promoting osteoblastogenesis in preference to adipogenesis in bone marrow mesenchymal progenitors (Takada et al. 2007). Wnt4, conventionally regarded as a non-canonical Wnt class (Wong et al. 1994), was found to potently enhance osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) isolated from human adult craniofacial tissue in vitro and bone formation in vivo, through activating p38 MAPK, which is known to positively regulate osteogenic differentiation induced by BMPs and other growth factors (Gallea et al. 2001; Guicheux et al. 2003). The inhibition of p38 MAPK abolished osteogenic differentiation of MSCs promoted by Wnt4.

Wnt11 belongs to the Wnt5a subclass which exerts diverse effects through activation of the non-canonical Wnt signaling pathway (Du et al. 1995). Recently, Rye and Chun demonstrated that Wnt11 stimulates the accumulation of type II collagen in articular chondrocytes (Ryu and Chun 2006). In three-dimensional alginate gels, WNT11 expression peaked at the late stage of chondrogenic differentiation of human MSCs (Xu et al. 2008). In Xenopus laevis and mouse P19 cells, signaling cascades activated by Wnt11 were crucial for initiating cardiogenesis; furthermore, Wnt11 not only inhibited β-catenin signaling, but also activated JNK, suggesting crosstalk between Wnt11 and MAPK signals (Pandur et al. 2002). In human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cell lines, overexpression of Wnt11 activated PKC signaling, which antagonized canonical Wnt signling through phosphorylation of β-catenin and reduction of T-cell factor (TCF)-mediated transcriptional activity (Toyama et al. 2010). However, few studies have been reported about the interplay between Wnt11 and MAPK signaling in the regulation of chondrogenesis.

Influence of MAPK signals on the Wnt pathway

Many studies showed that MAPKs participated in the regulation of Wnt pathway activities (Fig. 5). Expression of constitutively active MKK6, an upstream activator of p38 MAPK, in 293T cells was sufficient to increase the expression of β-catenin proteins, through direct phosphorylation of GSK3β protein both in vitro and in vivo; this phosphorylation was blocked by SB203580 or the knock-out of MKK3 and MKK6 (Ding et al. 2005; Thornton et al. 2008). Since MAPK signals were required for the phosphorylation of PPPS/TP motifs of endogenous LDL-related protein 6 (LRP6), Wnt3a-induced phosphorylation of endogenous LRP6 was significantly attenuated by knock-down of JNK1 and p38β. These results were further confirmed by pharmacological inhibition of p38 MAPK by SB203580 and that of JNK by SP600125 (Červenka et al. 2011). Rac1 can activate JNK2 to phosphorylate β-catenin, which is responsible for controlling limb outgrowth in mouse embryos (Wu et al. 2008). In Xenopus embryos, activation of JNK antagonized the canonical Wnt pathway through activating the nuclear export of β-catenin rather than its cytoplasmic stability (Liao et al. 2006). Many receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) systems facilitated Wnt/β-catenin signaling by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT (or alternatively Protein Kinase B, PKB) pathway through inhibiting GSK3 activity (Dailey et al. 2005). Interestingly, RTKs were also found to utilize ERK/LRP6 pathways for a direct phosphorylation of β-catenin to activate WNT/β-catenin signaling (Krejci et al. 2012).

Fig. 5.

Influence of MAPK signals on the Wnt pathway. Expression of constitutively active MKK6, an upstream activator of p38 MAPK, in 293T cells increased the expression of β-catenin proteins through direct phosphorylation of GSK3β protein both in vitro and in vivo; this phosphorylation was blocked by SB203580 or the knock-out (KO) of MKK3 and MKK6 (Thornton et al. 2008). Members of MAPKs such as ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, and JNK contributed to the phosphorylation of PPPS/TP clusters of endogenous LDL-related protein 6 (LRP6) phosphorylation, stimulating Wnt/β-catenin expression. Rac1, a small signaling G protein, could activate JNK2 to phosphorylate β-catenin (Wu et al. 2008). In Xenopus embryos, activation of JNK antagonized the canonical Wnt pathway through activating the nuclear export of β-catenin rather than maintaining its cytoplasmic stability (Liao et al. 2006). Receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) systems facilitated Wnt/β-catenin signaling by the PI3K/AKT pathway through inhibiting GSK3 activities (Dailey et al. 2005); RTKs could also phosphorylate β-catenin through involving ERK/LRP6 pathways to activate Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Krejci et al. 2012).

By changing key signals of the Wnt pathways, some critical transcriptional factor activities such as Sox9 or Runx2 are regulated, and eventually determine the differentiation fate of cells. BMP2, for instance, promotes chondrogenesis by activating p38 MAPK, which in turn down-regulates Wnt7a/β-catenin signaling. Inhibition of p38 MAPK using a dominant negative mutant led to sustained Wnt7a increase and decreased Sox9 expression, with consequent inhibition of pre-cartilage condensation and chondrogenic differentiation (Jin et al. 2006b). Similarly, TGFβ-1 mediated MAPK activation, which controls WNT7A gene expression and Wnt-mediated signaling through the intracellular β-catenin-TCF pathway, likely regulates N-cadherin expression and subsequent N-cadherin-mediated cell-adhesion complexes during the early steps of mesenchymal progenitor cell chondrogenesis (Tuli et al. 2003).

Environmental factors such as mechanical stress and cytokines may also activate the MAPK pathway. Static compressive loading of cartilage activates the MAPK pathway, which is also known as the stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK) pathway (Fanning et al. 2003; Tibbles and Woodgett 1999). Wnt/β-catenin signaling was not only involved in the bone response to mechanical loading (Robinson et al. 2006; Sawakami et al. 2006) but also associated with the response to mechanical damage to cartilage, which results in an increase in Wnt16 expression (Dell’accio et al. 2008). In MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells, activation of the pathway by treatment with a GSK3β inhibitor resulted in an anabolic bone formation response whereas the application of inhibitor combined with mechanical loading produced a synergistic effect on the expression of Wnt/β-catenin pathway target genes (Robinson et al. 2006). These results indicated that mechanical loading activated the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, at least in part, through the MAPK signaling pathway (Thornton et al. 2008).

Crosstalk of MAPK and Wnt signals in cartilage inflammation and regeneration

Osteoarthritis is a common disease, clinically manifested by joint pain, swelling, and impairment of joint function, which leads to disability and the need for joint replacement. Levels of β-catenin and cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) were increased in osteoarthritic and rheumatoid arthritic (RA) cartilage, suggesting that accumulation of β-catenin may contribute to the inflammatory responses of cartilage by inducing COX2 expression in chondrocytes of arthritis-affected cartilage (Kim et al. 2002). Activation of β-catenin in mature chondrocytes stimulated hypertrophy and matrix mineralization, evidenced by the expression of MMP13 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (Day et al. 2005; Tamamura et al. 2005). Overexpression of β-catenin in chondrocytes markedly increased expression of matrix degradation enzymes such as MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-7, MMP-9, membrane-type 3 MMP (MT3-MMP), and A Disintegrin And Metalloproteinase with Thrombospondin Motifs 5 (ADAMTS5) (Tamamura et al. 2005). Evidence from animal and in vitro models showed that knock-out of FRZB, which encodes a secreted Frizzled-related protein that can bind Wnt proteins, is more prone to lose proteoglycans from the articular cartilage in the knee (Lories et al. 2007). Through β-catenin stabilization and its nuclear translocation, Wnt signaling is associated with negative regulation of early chondrogenesis and stimulation of chondrocyte hypertrophy during development. Overexpression of Frzb1 lowered the expression of β-catenin (Enomoto-Iwamoto et al. 2002). The FRZB−/− mice may induce OA formation through up-regulation and stabilization of β-catenin in the canonical Wnt pathway. Interestingly, Frzb deficiency also resulted in thicker cortical bone, with increased stiffness and higher cortical appositional bone formation after loading, seemingly supporting the hypothesized inverse relationship between OA and osteoporosis (Dequeker et al. 2003). In addition, canonical Wnt signaling is influenced by local factors, including alterations in glycosaminoglycan sulfation, cartilage matrix content, TGFβ, and vitamin D. It is interesting to note that the MMPs and ADAMTSs boosted by experimental activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway are quite similar to those triggered by treatment with IL-1β or tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) in chondrocytes (Burrage et al. 2006). However, the role of β-catenin in the homeostasis of cartilage is still controversial, as suggested by Zhu et al. that inhibition of β-catenin signaling in articular chondrocytes caused increased cell apoptosis and articular cartilage destruction in COL2A1-ICAT-transgenic mice (Zhu et al. 2008). It is assumed that the Wnt/β-catenin pathway may be part of integrated signal transduction mechanisms through which chondrocytes respond to deranging and catabolic cues, activate the expression of MMP and ADAMTS genes and corresponding proteolytic activity, and undermine their phenotypic status and ultimate tissue function (Yuasa et al. 2008).

Accumulating evidence supports a central regulatory role of MAPK in mediating inflammatory and matrix degrading processes that contribute to joint tissue destruction in OA. Both OA and normal chondrocytes expressed p38 MAPK; however, OA chondrocytes showed a much higher phosphorylated p38 MAPK level compared to normal chondrocytes (Fan et al. 2007; Takebe et al. 2011). Activated JNK was detected in the cytoplasm of OA chondrocytes, but not in healthy controls (Clancy et al. 2001). In a dog model of surgically induced OA, p38 MAPK, JNK, and ERK1/2 were all activated to a greater degree compared to those in normal tissue (Boileau et al. 2006). Among the possible MAPK therapeutic targets for OA or RA, p38 MAPK is generally considered to be the most promising, as p38 MAPK isoforms have been implicated in the regulation of processes (such as migration and accumulation of leucocytes and production of cytokines and pro-inflammatory mediators and angiogenesis) which promote disease pathogenesis (Korb et al. 2006; Schett et al. 2000). p38 MAPK inhibitors have been proven effective in reducing clinical severity, paw swelling, inflammation, cartilage breakdown, and bone erosion in a rat streptococcal cell wall arthritis model (Mbalaviele et al. 2006; Mclay et al. 2001), a collagen-induced-arthritis (CIA) model in mice (Medicherla et al. 2006), and adjuvant and CIA models in rats (Badger et al. 2000; Nishikawa et al. 2003). JNK appears to be a critical MAPK pathway for IL-1-induced collagenase gene expression in synoviocytes and joint arthritis (Han et al. 1999; Han et al. 2001). The JNK inhibitor SP600125 completely blocked not only IL-1-induced accumulation of phosphorylated Jun and induction of c-Jun transcription in synoviocytes but also the AP-1 binding and collagenase mRNA accumulation (Han et al. 2001). ERK is known to be involved in the regulation of IL-6, IL-12, IL-23, and TNF-α synthesis, suggesting a possible involvement of ERK in joint damage associated with pro-inflammatory cytokine production by macrophages (Feng et al. 1999; Goodridge et al. 2003). ERK inhibitors have been found to be successful in reducing inflammation in an experimental OA model in rabbits (Pelletier et al. 2003); therapeutic intervention with the goal of MEK1/2 inhibition may have interesting potential for the development of agents for the treatment of OA. Due to important roles in transducing inflammation and joint destruction, MAPK signals are key molecular targets for therapeutic intervention in inflammatory diseases such as OA and RA. However, inhibitors targeting ablation or reduction of MAPK activity are likely to have serious side effects (Thalhamer et al. 2008).

Recently, several non-canonical Wnt isoforms such as Wnt5a and Wnt11 were reported to be involved in IL-1β-induced dedifferentiation of articular chondrocytes (Ryu and Chun 2006). Wnt5a was detectably expressed in OA and RA and was involved in IL-1β-induced up-regulation of MMP-1, MMP-3, MMP-9, and MMP-13 in primary TMJ condylar chondrocyte via the JNK pathway, suggesting the role of Wnt5a in arthritic pathology and regulation of cartilage destruction. Furthermore, blockage of JNK signaling impaired the Wnt5a-induced up-regulation of MMPs (Ge et al. 2009). This finding indicates that crosstalk between Wnt5a and JNK contributes to the pathogenesis of OA; meanwhile, disturbance of or intervention in the interaction between these signals might provide new targets for OA treatment. Several studies have indicated that signaling pathways involving MAPKs mediate the catabolic response of chondrocytes to those inflammatory cytokines; specific inhibitors to those pathways can counteract cytokine effects on matrix protease gene expression (Geng et al. 1996; Hwang et al. 2005; Kumar et al. 2001; Liacini et al. 2002; Ryu et al. 2002).

Besides activation of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, the occurrence of OA may also take the route in which articular chondrocytes lose their differentiated phenotype and obtain a behavior with similarities to terminal differentiating chondrocytes (hypertrophy-like), as can be found in the growth plate of growing individuals (Dreier 2010; von der Mark et al. 1992). Chondrocytes in OA cartilage show an aberrant phenotype and actively produce cartilage-degrading enzymes, such as MMP-13 and aggrecanases (Moldovan et al. 1997; Shlopov et al. 2000; Song et al. 2007). The higher expression of hypertrophic chondrocyte markers, type X collagen and MMP-13 (Kirsch and Von der 1992; Nurminskaya and Linsenmayer 1996) in OA, suggests a correlation between hypertrophy and OA. Some studies demonstrated that Wnt signaling promoted chick chondrocyte hypertrophy through induction of the bone and cartilage-related transcription factor Runx2. Dong et al. reported that β-catenin is able to induce RUNX2 and COL10A1 transcription as the molecular mechanism through which Wnt signaling regulates chondrocyte hypertrophy (Dong et al. 2006). Protein levels of β-catenin, which accumulates in OA chondrocytes, are very low in differentiated articular chondrocytes; however, low levels of β-catenin were up-regulated during phenotypic loss after a serial monolayer culture. Ectopic expression or inhibition of β-catenin degradation caused cessation of cartilage-specific ECM molecule synthesis via activation of β-catenin-Tcf/Lef transcriptional activity (Ryu et al. 2002). Activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling is usually accompanied by a shift in chondrocyte cytoarchitecture. This event may result from a reduction of proteoglycan pericellular matrix, or interactions between chondrocyte surface and substrate or fibrillar components such as collagen or fibronectin, which could change intracellular signaling and up-regulate cell adhesion pathways such as that of MAPK (Gemba et al. 2002). Because the loss of a differentiated phenotype of chondrocytes is associated with cartilage destruction during arthritis (Sandell and Aigner 2001), the canonical Wnt pathway-mediated cell phenotype change via crosstalk with MAPK signals is another pathway through which OA forms. For the non-canonical Wnt signal pathway, Wnt5a has been reported as a key parameter influencing the phenotypic stability of chondrocytes (Benya et al. 1982; Yuasa et al. 2008). Wnt5a inhibits type II collagen expression in rabbit TMJ condylar chondrocytes (Ge et al. 2009), suggesting that Wnt5a signaling may regulate pathologic cartilage degeneration by inducing chondrocyte dedifferentiation (Ryu and Chun 2006). Increased p38 activity is accompanied by type X collagen staining in osteochondrocytes and marginal synovial cells in a mouse OA model (Seto et al. 2004). During monolayer culture, p38 MAPK was responsible for the loss of chondrocyte phenotypes including type II collagen and Sox9 while the blockade of p38 MAPK enhanced chondrocyte phenotypes, which suggests a blockade of dedifferentiation (Rosenzweig et al. 2013). Inhibition of p38 signaling in chondrocytes resulted in decreased expression of the COL10A1 gene (Beier and LuValle 1999; Stanton et al. 2004; Zhen et al. 2001).

Conclusion and Future Directions

Although there is an increasing awareness of the importance of MAPK and Wnt signaling pathways in regulating cell activities and relevant diseases such as cancer, their interaction networks and potential roles in disease are still not fully appreciated, especially in the cartilage regeneration area (Table 1). Cartilage differentiation and maintenance of homeostasis are finely tuned by a complex network of signaling molecules; interplay of these signaling pathways leads to changes in cell activities and eventually influences their differentiation fates. Over the past two decades, extensive studies on Wnt and MAPK regulation of chondrogenesis and cartilage development have shown that Wnt and MAPK signals have both positive and negative regulatory effects on cartilage development. Increasing evidence indicates the involvement of Wnt and MAPK signals in the regulation of differentiated chondrocyte functions and cartilage disease.

Table 1.

Highlighted references related to the crosstalk between Wnt and MAPK pathways in varied cell types, especially its influence in the regulation of chondrogenesis

| Cell type | Approach | Signal | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse F9 teratocarcino ma cells | Gene knockout (siRNAs targeting p38α MAPK) and chemical inhibitor (SB203580 targeting p38 MAPK) | P38 MAPK and Wnt5a | Wnt5a activated p38 MAPK pathway, which feeds into the Wnt5a/cyclic GMP/Ca2+/NF-AT pathway | Ma and Wang 2007 |

| Gene knockout (siRNA targeting Dvl-1, Dvl-2, and Dvl-3) and chemical inhibitors (SB203580 targeting p38 MAPK, SP600125 targeting JNK) | Wnt3a and JNK | Suppression of either Dvl-1 or Dvl-3 but not Dvl-2 abolished Wnt3a activation of JNK; SP600125 but not SB203580 blocked Wnt3a activation of JNK | Bikkavilli et al. 2008a | |

| Gene knockout (siRNA targeting Gα0, Gαs, Gαq, Gα11, JNK1) and chemical inhibitor (SB203580 targeting p38 MAPK) | Wnt3a and JNK | Wnt3a activated p38 MAPK while Gαs, and Gαq knockout attenuated this effect; SB203580 attenuated Wnt3a induced accumulation of β-catenin | Bikkavilli et al. 2008b | |

| Mouse C3H10T1/2 mesenchymal cells | Gene transfection (dominant-negative p38, MEK3, and MEK6) and chemical inhibitors (SB203580 targeting p38 MAPK, MEK inhibitor U0126) | Wnt3a, ERK and P38 MAPK | Wnt3a induced a rapid and transient activation of p38 MAPK and ERK; SB203580 and dominant-negative p38, MEK3 and MEK6 led to inhibition of β-catenin expression | Caverzasio and Manen 2007 |

| Mouse NIH3T3 cells | Gene transfection (recombinant Wnt3a) and gene knockout (siRNA targeting β-catenin, ERK1, ERK2) | ERK and Wnt/β-catenin | Wnt3a stimulated the proliferation of fibroblast cells, at least in part, via activation of the ERK and Wnt/β-catenin pathways | Yun et al. 2005 |

| Mouse Stromal cell clone (ST2) | Gene transfection (retroviruses expressing GqI, Dkk1, Dvl-2 derivatives, N17Rac1, N17Cdc42, and V12Rac1) and gene knockout (siRNA targeting β-catenin) | Wnt/β-catenin and JNK2 | JNK2 kinase activated Rac1 resulting in β-catenin phosphorylation and canonical Wnt signaling activation | Wu et al. 2008 |

| Chicken mesenchymal cells from embryo wing buds | Gene transfection (dominant-negative Tcf-4) | Wnt3a and JNK | Wnt3a inhibited chondrogenesis by stabilizing cell-cell adhesion; Wnt3a caused dedifferentiation of chondrocytes by activation of the β-catenin-Tcf/Lef transcriptional complex and the c-Jun/Ap-1 pathway | Hwang et al. 2005 |

| Gene transfection (retrovirus transfection targeting Wnt5a, Wnt7a) | N-cadherin (MAPKs) and Wnt7a, Wnt5a | Retrovirally mediated misexpression of Wnt7a inhibited in vitro chondrogenesis whereas Wnt5a did not; Wnt signaling in chondrogenesis was likely to involve modulation of N-cadherin expression | Tufan and Tuan 2001 | |

| Gene transfection (RCAS constructs of Wnt5a or RCAS vector); gene knockout (siRNA targeting Wnt5a); and chemical inhibitors (PD169316 targeting p38 MAPK, GF109203X targeting PKC-α) | Wnt5a and p38 MAPK | Overexpression of Wnt5a or treatment with TGFβ3 stimulated the activation of PKC-α and p38 MAPK, both positively regulated chondrogenic differentiation; inactivation of PKC-a and p38 MAPK by specific inhibitors abrogated chondrogenesis stimulated by both TGFβ3 and Wnt5a | Jin et al. 2006a | |

| Gene transfection (dominant-negative p38 MAPK) | Wnt7a/β-catenin and p38 MAPK | BMP2 promoted chondrogenesis by activating p38 MAPK, which in turn down-regulated Wnt7a/β-catenin signaling responsible for proteasomal degradation of Sox9 | Jin et al. 2006b | |

| Chemical inhibitors (SP600125 targeting JNK, Src kinase inhibitor I targeting Src) | Wnt5b and JNK | Wnt5b not only inhibited chondrocyte hypertrophy but also promoted cellular migration through the JNK-dependent activation of Src and subsequent cadherin receptor turnover | Bradley and Drissi 2011 | |

| Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK 293) cell line | Gene transfection (GSK3β mutant constructs, dominant-negative ERK1/2, constitutively active GSK3β); gene knockout (siRNA targeting β-catenin, siRNA targeting ERK1/2); and chemical inhibitors (PD98059 targeting MEK1, LY294002 targeting PI3K, calphostin C targeting PKC) | P38 MAPK; ERK1/2; and Wnt/β-catenin | ERK activation led to phosphorylation and inactivation of GSK3β, resulting in release of β-catenin, which was translocated into nucleus and facilitated cell proliferation | Ding et al. 2005 |

| Gene transfection (plasmids for wild type p38 MAPK, constitutively active MEK6, mutant GSK3β) and chemical inhibitors (SB203580 targeting p38 MAPK, Wortmanin targeting PI3K) | Tak1 MAPK and Wnt/β-catenin | p38 MAPK inactivated GSK3β by direct phosphorylation at its C terminus; this inactivation led to an accumulation of β-catenin in nucleus | Thornton et al. 2008 | |

| Gene transfection (FGFR3 vectors, LRP6 variant vectors, plasmids expressing V5-tagged FGFR2, EGFR, and TRKA) and chemical inhibitor (U0126 targeting ERK1/2) | Wnt/β-catenin and ERK1/2 | Wnt/β-catenin was activated by FGFR2/3, EGFR, and TRKA kinases, which depend on ERK-mediated phosphorylation of Wnt co-receptor LRP6 | Krejci et al. 2012 | |

| Gene knockout (siRNAs targeting MAPK1, MAPK3, MAPK8, MAPK11) and chemical inhibitors (BIRB796 and SB203580 targeting p38 MAPK, SP600125 targeting JNK, U0126 targeting ERK1/2) | MAPKs and Wnt/β-catenin | Several MAPKs, such as p38, ERK1/2, and JNK1, were sufficient and required for the phosphorylation of PPPS/TP motifs of LRP6, which is a co-receptor of Wnts and a key regulator of Wnt/β-catenin pathway | Cervenka et al. 2011 | |

| Human trabecular bone-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells (MPCs) | Gene transfection (plasmid containing human type II collagen α1, plasmid of pAGC1 containing human aggrecan promoter) and chemical inhibitors (SB203580 targeting p38 MAPK, PD98059 targeting ERK-1 specific MEK1, SP600125 targeting JNK) | MAPKs and Wnt7a | TGFβ1 treatment initiated and maintained chondrogenesis of MPCs through the differential chondro-stimulatory activities of p38, ERK1, and to a lesser extent, JNK; TGFβ1-mediated MAPK activation controlled Wnt7a gene expression and Wnt-mediated signaling through the intracellular β-catenin-TCF pathway, which likely regulated N-cadherin expression and subsequent cell-adhesion complexes during the early steps of MPC chondrogenesis | Tuli et al. 2003 |

| Rabbit temporom and ibular joint (TMJ) condylar chondrocytes | Gene transfection (β-catenin-Tcf/Lef expression plasmid, Wnt5a expression vector) | Wnt5a and JNK | Activation of Wnt5a signaling by IL-1β induced the expression of MMPs via the JNK pathway | Ge et al. 2009 |

| Xenopus embryo | Gene transfection [constitutive-active JNK plasmid (Flag-MKK7-hJNK1), antisense oligo against Dsh] and chemical inhibitor (SP600125 targeting JNK) | Wnt/β-catenin and JNK | JNK antagonized the canonical Wnt pathway by regulating the nucleocytoplasmic transport of β-catenin | Liao et al. 2006 |

Recent evidence from both animal experiments and clinical samples demonstrated the role of both Wnt and MAPK signaling in OA pathology, making these pathways attractive targets for therapy. Some chemicals and drugs targeting MAPK or Wnt have been designed and applied clinically; while some are effective in treatment of OA, their side effects have drawn concern. Direct targeting to Wnt or MAPK has been reported to be too risky, because of the critical role of these signals in the maintenance of articular chondrocyte stability. A promising method would be to identify the mis-regulated genes in the Wnt or MAPK pathways, and try to determine balanced therapeutic targets. The ideal therapeutic goal would be treatment with few or even no side effects to patients. In order to achieve the goal of clinical application, comprehensive appreciation and meticulous evaluation of interactions of these signaling pathways are not only necessary but also required. Future research may focus on elucidation of the network between MAPK and Wnt signaling interplays and exploration of clinical application in cartilage regeneration by intervening in specific signaling pathways.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Suzanne Danley for help in editing the manuscript. This project was partially supported by the AO Foundation (S-12-19P) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (1 R03 AR062763-01A1).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Ying Zhang, Stem Cell and Tissue Engineering Laboratory, Department of Orthopaedics, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV 26506 USA. Mechanical & Aerospace Engineering, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV 26506 USA.

Tyler Pizzute, Stem Cell and Tissue Engineering Laboratory, Department of Orthopaedics, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV 26506 USA. Exercise Physiology, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV 26506 USA.

Ming Pei, Stem Cell and Tissue Engineering Laboratory, Department of Orthopaedics, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV 26506 USA. Exercise Physiology, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV 26506 USA. Mechanical & Aerospace Engineering, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV 26506 USA.

References

- Akiyama H, Lyons JP, Mori-Akiyama Y, Yang X, Zhang R, Zhang Z, Deng JM, Taketo MM, Nakamura T, Behringer RR, McCrea PD, de Crombrugghe B. Interactions between Sox9 and beta-catenin control chondrocyte differentiation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1072–1087. doi: 10.1101/gad.1171104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger AM, Griswold DE, Kapadia R, Blake S, Swift BA, Hoffman SJ, Stroup GB, Webb E, Rieman DJ, Gowen M, Boehm JC, Adams JL, Lee JC. Disease-modifying activity of SB 242235, a selective inhibitor of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, in rat adjuvant-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:175–183. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200001)43:1<175::AID-ANR22>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beier F, LuValle P. Serum induction of the collagen X promoter requires the Raf/MEK/ERK and p38 pathways. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;262:50–54. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benya PD, Shaffer JD. Dedifferentiated chondrocytes reexpress the differentiated collagen phenotype when cultured in agarose gels. Cell. 1982;30:215–224. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikkavilli RK, Feigin ME, Malbon CC. G alpha o mediates WNT-JNK signaling through dishevelled 1 and 3, RhoA family members, and MEKK 1 and 4 in mammalian cells. J Cell Sci. 2008a;121:234–245. doi: 10.1242/jcs.021964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikkavilli RK, Feigin ME, Malbon CC. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase regulates canonical Wnt-beta-catenin signaling by inactivation of GSK3beta. J Cell Sci. 2008b;121:3598–3607. doi: 10.1242/jcs.032854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobick BE, Kulyk WM. MEK-ERK signaling plays diverse roles in the regulation of facial chondrogenesis. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:1079–192. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boileau C, Martel-Pelletier J, Brunet J, Schrier D, Flory C, Boily M, Pelletier JP. PD-0200347, an alpha2delta ligand of the voltage gated calcium channel, inhibits in vivo activation of the Erk1/2 pathway in osteoarthritic chondrocytes: a PKC alpha dependent effect. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:573–580. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.041855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley EW, Drissi MH. WNT5A regulates chondrocyte differentiation through differential use of the CaN/NFAT and IKK/NF-kappaB pathways. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:1581–1593. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley EW, Drissi MH. Wnt5b regulates mesenchymal cell aggregation and chondrocyte differentiation through the planar cell polarity pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:1683–1693. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrage PS, Mix KS, Brinckerhoff CE. Matrix metalloproteinases: role in arthritis. Front Biosci. 2006;11:529–43. doi: 10.2741/1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancedda R, Castagnola P, Cancedda FD, Dozin B, Quarto R. Developmental control of chondrogenesis and osteogenesis. Int J Dev Biol. 2000;44:707–714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caverzasio J, Manen D. Essential role of Wnt3a-mediated activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 for the stimulation of alkaline phosphatase activity and matrix mineralization in C3H10T1/2 mesenchymal cells. Endocrinology. 2007;148:5323–5330. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Červenka I, Wolf J, Mašek J, Krejci P, Wilcox WR, Kozubík A, Schulte G, Gutkind JS, Bryja V. Mitogen-activated protein kinases promote WNT/beta-catenin signaling via phosphorylation of LRP6. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:179–189. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00550-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang SH, Oh CD, Yang MS, Kang SS, Lee YS, Sonn JK, Chun JS. Protein kinase C regulates chondrogenesis of mesenchymes via mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:19213–19219. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.19213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church VL, Francis-West P. Wnt signalling during limb development. Int J Dev Biol. 2002;46:927–936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy R, Rediske J, Koehne C, Stoyanovsky D, Amin A, Attur M, Iyama K, Abramson SB. Activation of stress-activated protein kinase in osteoarthritic cartilage: evidence for nitric oxide dependence. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2001;9:294–299. doi: 10.1053/joca.2000.0388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailey L, Ambrosetti D, Mansukhani A, Basilico C. Mechanisms underlying differential responses to FGF signaling. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:233–247. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day TF, Guo X, Garrett-Beal L, Yang Y. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in mesenchymal progenitors controls osteoblast and chondrocyte differentiation during vertebrate skeletogenesis. Dev Cell. 2005;8:739–750. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell’accio F, De Bari C, Eltawil NM, Vanhummelen P, Pitzalis C. Identification of the molecular response of articular cartilage to injury, by microarray screening: Wnt-16 expression and signaling after injury and in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1410–1421. doi: 10.1002/art.23444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dequeker J, Aerssens J, Luyten FP. Osteoarthritis and osteoporosis: clinical and research evidence of inverse relationship. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2003;15:426–439. doi: 10.1007/BF03327364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Q, Xia W, Liu JC, Yang JY, Lee DF, Xia J, Bartholomeusz G, Li Y, Pan Y, Li Z, Bargou RC, Qin J, Lai CC, Tsai FJ, Tsai CH, Hung MC. Erk associates with and primes GSK-3beta for its inactivation resulting in upregulation of beta-catenin. Mol Cell. 2005;19:159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong YF, Soung do Y, Schwarz EM, O’Keefe RJ, Drissi H. Wnt induction of chondrocyte hypertrophy through the Runx2 transcription factor. J Cell Physiol. 2006;208:77–86. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreier R. Hypertrophic differentiation of chondrocytes in osteoarthritis: the developmental aspect of degenerative joint disorders. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:216. doi: 10.1186/ar3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du SJ, Purcell SM, Christian JL, McGrew LL, Moon RT. Identification of distinct classes and functional domains of Wnts through expression of wild-type and chimeric proteins in Xenopus embryos. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2625–2634. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto-Iwamoto M, Kitagaki J, Koyama E, Tamamura Y, Wu C, Kanatani N, Koike T, Okada H, Komori T, Yoneda T, Church V, Francis-West PH, Kurisu K, Nohno T, Pacifici M, Iwamoto M. The Wnt antagonist Frzb-1 regulates chondrocyte maturation and long bone development during limb skeletogenesis. Dev Biol. 2002;251:142–156. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Z, Söder S, Oehler S, Fundel K, Aigner T. Activation of interleukin-1 signaling cascades in normal and osteoarthritic articular cartilage. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:938–946. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanning PJ, Emkey G, Smith RJ, Grodzinsky AJ, Szasz N, Trippel SB. Mechanical regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in articular cartilage. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:50940–50948. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng GJ, Goodridge HS, Harnett MM, Wei XQ, Nikolaev AV, Higson AP, Liew FY. Extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK) and p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases differentially regulate the lipopolysaccharide-mediated induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase and IL-12 in macrophages: Leishmania phosphoglycans subvert macrophage IL-12 production by targeting ERK MAP kinase. J Immunol. 1999;163:6403–6412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallea S, Lallemand F, Atfi A, Rawadi G, Ramez V, Spinella-Jaegle S, Kawai S, Faucheu C, Huet L, Baron R, Roman-Roman S. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades is involved in regulation of bone morphogenetic protein-2-induced osteoblast differentiation in pluripotent C2C12 cells. Bone. 2001;28:491–498. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00415-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Ma X, Meng J, Zhang C, Ma K, Zhou C. Role of Wnt-5A in interleukin-1beta-induced matrix metalloproteinase expression in rabbit temporomandibular joint condylar chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:2714–2722. doi: 10.1002/art.24779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemba T, Valbracht J, Alsalameh S, Lotz M. Focal adhesion kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinases are involved in chondrocyte activation by the 29-kDa amino-terminal fibronectin fragment. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:907–911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109690200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng Y, Valbracht J, Lotz M. Selective activation of the mitogen activated protein kinase subgroups c-Jun NH2 terminal kinase and p38 by IL-1 and TNF in human articular chondrocytes. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2425–2430. doi: 10.1172/JCI119056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodridge HS, Harnett W, Liew FY, Harnett MM. Differential regulation of interleukin-12 p40 and p35 induction via Erk mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent and -independent mechanisms and the implications for bioactive IL-12 and IL-23 responses. Immunology. 2003;109:415–425. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2003.01689.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guicheux J, Lemonnier J, Ghayor C, Suzuki A, Palmer G, Caverzasio J. Activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and c-Jun-NH2-terminal kinase by BMP-2 and their implication in the stimulation of osteoblastic cell differentiation. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:2060–2068. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.11.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnell LM1, Jonason JH, Loiselle AE, Kohn A, Schwarz EM, Hilton MJ, O’Keefe RJ. TAK1 regulates cartilage and joint development via the MAPK and BMP signaling pathways. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:1784–1797. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Jin J, Cooper LF. Dissection of sets of genes that control the character of wnt5a-deficient mouse calvarial cells. Bone. 2008;43:961–971. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Day TF, Jiang X, Garrett-Beal L, Topol L, Yang Y. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is sufficient and necessary for synovial joint formation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2404–2417. doi: 10.1101/gad.1230704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Z, Boyle DL, Aupperle KR, Bennett B, Manning AM, Firestein GS. Jun N-terminal kinase in rheumatoid arthritis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;291:124–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Z, Boyle DL, Chang L, Bennett B, Karin M, Yang L, Manning AM, Firestein GS. c-Jun N-terminal kinase is required for metalloproteinase expression and joint destruction in inflammatory arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:73–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI12466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann C, Tabin CJ. Dual roles of Wnt signaling during chondrogenesis in the chicken limb. Development. 2000;127:3141–3159. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.14.3141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann C. A Wnt canon orchestrating osteoblastogenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill TP, Später D, Taketo MM, Birchmeier W, Hartmann C. Canonical Wnt/beta-catenin signaling prevents osteoblasts from differentiating into chondrocytes. Dev Cell. 2005;8:727–738. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Hilton MJ, Tu X, Yu K, Ornitz DM, Long F. Sequential roles of Hedgehog and Wnt signaling in osteoblast development. Development. 2005;132:49–60. doi: 10.1242/dev.01564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SG, Yu SS, Lee SW, Chun JS. Wnt-3a regulates chondrocyte differentiation via c-Jun/AP-1 pathway. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:4837–4842. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.07.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishitani T, Kishida S, Hyodo-Miura J, Ueno N, Yasuda J, Waterman M, Shibuya H, Moon RT, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Matsumoto K. The TAK1-NLK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade functions in the Wnt-5a/Ca(2+) pathway to antagonize Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:131–139. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.1.131-139.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin EJ, Lee SY, Choi YA, Jung JC, Bang OS, Kang SS. BMP-2-enhanced chondrogenesis involves p38 MAPK-mediated down-regulation of Wnt-7a pathway. Mol Cells. 2006b;22:353–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin EJ, Park JH, Lee SY, Chun JS, Bang OS, Kang SS. Wnt-5a is involved in TGF-beta3-stimulated chondrogenic differentiation of chick wing bud mesenchymal cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006a;38:183–195. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ML, Rajamannan N. Diseases of Wnt signaling. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2006;7:41–49. doi: 10.1007/s11154-006-9003-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krejci P, Aklian A, Kaucka M, Sevcikova E, Prochazkova J, Masek JK, Mikolka P, Pospisilova T, Spoustova T, Weis M, Paznekas WA, Wolf JH, Gutkind JS, Wilcox WR, Kozubik A, Jabs EW, Bryja V, Salazar L, Vesela I, Balek L. Receptor tyrosine kinases activate canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling via MAP kinase/LRP6 pathway and direct β-catenin phosphorylation. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35826. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami Y, Wada N, Nishimatsu SI, Ishikawa T, Noji S, Nohno T. Involvement of Wnt-5a in chondrogenic pattern formation in the chick limb bud. Dev Growth Differ. 1999;41:29–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-169x.1999.00402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SJ, Im DS, Kim SH, Ryu JH, Hwang SG, Seong JK, Chun CH, Chun JS. Beta-catenin regulates expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in articular chondrocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;296:221–226. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00824-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch T, von der MK. Remodelling of collagen types I, II and X and calcification of human fetal cartilage. Bone Miner. 1992;18:107–117. doi: 10.1016/0169-6009(92)90851-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korb A, Tohidast-Akrad M, Cetin E, Axmann R, Smolen J, Schett G. Differential tissue expression and activation of p38 MAPK alpha, beta, gamma, and delta isoforms in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2745–2756. doi: 10.1002/art.22080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krens SF, Spaink HP, Snaar-Jagalska BE. Functions of the MAPK family in vertebrate-development. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:4984–4990. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Votta BJ, Rieman DJ, Badger AM, Gowen M, Lee JC. IL-1- and TNF-induced bone resorption is mediated by p38 mitogen activated protein kinase. J Cell Physiol. 2001;87:294–303. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liacini A, Sylvester J, Li WQ, Zafarullah M. Inhibition of interleukin-1-stimulated MAP kinases, activating protein-1 (AP-1) and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kappa B) transcription factors downregulates matrix metalloproteinase gene expression in articular chondrocytes. Matrix Biol. 2002;21:251–262. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(02)00007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao G, Tao Q, Kofron M, Chen JS, Schloemer A, Davis RJ, Hsieh JC, Wylie C, Heasman J, Kuan CY. Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) prevents nuclear beta-catenin accumulation and regulates axis formation in Xenopus embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16313–16318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602557103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan CY, Nusse R. The Wnt signaling pathway in development and disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:781–810. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.113126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lories RJ, Peeters J, Bakker A, Tylzanowski P, Derese I, Schrooten J, Thomas JT, Luyten FP. Articular cartilage and biomechanical properties of the long bones in Frzb-knockout mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:4095–4103. doi: 10.1002/art.23137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Wang HY. Mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 regulates the Wnt/cyclic GMP/Ca2+ non-canonical pathway. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:28980–28990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702840200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masckauchán TN, Agalliu D, Vorontchikhina M, Ahn A, Parmalee NL, Li CM, Khoo A, Tycko B, Brown AM, Kitajewski J. Wnt5a signaling induces proliferation and survival of endothelial cells in vitro and expression of MMP-1 and Tie-2. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:5163–5172. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-04-0320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbalaviele G, Anderson G, Jones A, De Ciechi P, Settle S, Mnich S, Thiede M, Abu-Amer Y, Portanova J, Monahan J. Inhibition of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase prevents inflammatory bone destruction. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:1044–1053. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.100362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mclay LM, Halley F, Souness JE, McKenna J, Benning V, Birrell M, Burton B, Belvisi M, Collis A, Constan A, Foster M, Hele D, Jayyosi Z, Kelley M, Maslen C, Miller G, Ouldelhkim MC, Page K, Phipps S, Pollock K, Porter B, Ratcliffe AJ, Redford EJ, Webber S, Slater B, Thybaud V, Wilsher N. The discovery of RPR 200765A, a p38 MAP kinase inhibitor displaying a good oral anti-arthritic efficacy. Bioorg Med Chem. 2001;9:537–554. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(00)00331-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicherla S, Ma JY, Mangadu R, Jiang Y, Zhao JJ, Almirez R, Kerr I, Stebbins EG, O’Young G, Kapoun AM, Luedtke G, Chakravarty S, Dugar S, Genant HK, Protter AA. A selective p38 alpha mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor reverses cartilage and bone destruction in mice with collagen-induced arthritis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;318:132–141. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.098020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneghini MD, Ishitani T, Carter JC, Hisamoto N, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Thorpe CJ, Hamill DR, Matsumoto K, Bowerman B. MAP kinase and Wnt pathways converge to downregulate an HMG-domain repressor in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1999;399:793–797. doi: 10.1038/21666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldovan F, Pelletier JP, Hambor J, Cloutier JM, Martel-Pelletier J. Collagenase-3 (matrix metalloprotease 13) is preferentially localized in the deep layer of human arthritic cartilage in situ:in vitro mimicking effect by transforming growth factor beta. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1653–1661. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami S, Kan M, McKeehan WL, de Crombrugghe B. Up-regulation of the chondrogenic Sox9 gene by fibroblast growth factors is mediated by the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:1113–1118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Shirai T, Morishita S, Uchida S, Saeki-Miura K, Makishima F. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase functionally contributes to chondrogenesis induced by growth/differentiation factor-5 in ATDC5 cells. Exp Cell Res. 1999;250:351–363. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa M, Myoui A, Tomita T, Takahi K, Nampei A, Yoshikawa H. Prevention of the onset and progression of collagen-induced arthritis in rats by the potent p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor FR167653. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2670–2681. doi: 10.1002/art.11227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurminskaya M, Linsenmayer TF. Identification and characterization of up-regulated genes during chondrocyte hypertrophy. Dev Dyn. 1996;206:260–271. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199607)206:3<260::AID-AJA4>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberlender SA, Tuan RS. Expression and functional involvement of N-cadherin in embryonic limb chondrogenesis. Development. 1994;120:177–187. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.1.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh CD, Chang SH, Yoon YM, Lee SJ, Lee YS, Kang SS, Chun JS. Opposing role of mitogen-activated protein kinase subtypes, erk-1/2 and p38, in the regulation of chondrogenesis of mesenchymes. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5613–5619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandur P, Läsche M, Eisenberg LM, Kühl M. Wnt-11 activation of a non-canonical Wnt signalling pathway is required for cardiogenesis. Nature. 2002;418:636–641. doi: 10.1038/nature00921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier JP, Fernandes JC, Brunet J, Moldovan F, Schrier D, Flory C, Martel-Pelletier J. In vivo selective inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1/2 in rabbit experimental osteoarthritis is associated with a reduction in the development of structural changes. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:1582–1593. doi: 10.1002/art.11014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JA, Chatterjee-Kishore M, Yaworsky PJ, Cullen DM, Zhao W, Li C, Kharode Y, Sauter L, Babij P, Brown EL, Hill AA, Akhter MP, Johnson ML, Recker RR, Komm BS, Bex FJ. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is a normal physiological response to mechanical loading in bone. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:31720–31728. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602308200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig DH, Ou SJ, Quinn TM. P38 mitogen-activated protein kinase promotes dedifferentiation of primary articular chondrocytes in monolayer culture. J Cell Mol Med. 2013;17:508–517. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu JH, Chun JS. Opposing roles of WNT-5A and WNT-11 in interleukin-1beta regulation of type II collagen expression in articular chondrocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:22039–22047. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601804200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu JH, Kim SJ, Kim SH, Oh CD, Hwang SG, Chun CH, Oh SH, Seong JK, Huh TL, Chun JS. Regulation of the chondrocyte phenotype by beta-catenin. Development. 2002;129:5541–5550. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.23.5541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandell LJ, Aigner T. Articular cartilage and changes in arthritis. An introduction: cell biology of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res. 2001;3:107–113. doi: 10.1186/ar148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawakami K, Robling AG, Ai M, Pitner ND, Liu D, Warden SJ, Li J, Maye P, Rowe DW, Duncan RL, Warman ML, Turner CH. The Wnt co-receptor LRP5 is essential for skeletal mechanotransduction but not for the anabolic bone response to parathyroid hormone treatment. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:23698–23711. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601000200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schett G, Tohidast-Akrad M, Smolen JS, Schmid BJ, Steiner CW, Bitzan P, Zenz P, Redlich K, Xu Q, Steiner G. Activation, differential localization, and regulation of the stress-activated protein kinases, extracellular signal-regulated kinase, c-JUN N-terminal kinase, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, in synovial tissue and cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:2501–2512. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200011)43:11<2501::AID-ANR18>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seghatoleslami MR, Roman-Blas JA, Rainville AM, Modaressi R, Danielson KG, Tuan RS. Progression of chondrogenesis in C3H10T1/2 cells is associated with prolonged and tight regulation of ERK1/2. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:1129–1144. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto H, Kamekura S, Miura T, Yamamoto A, Chikuda H, Ogata T, Hiraoka H, Oda H, Nakamura K, Kurosawa H, Chug UI, Kawaguchi H, Tanaka S. Distinct roles of Smad pathways and p38 pathways in cartilage-specific gene expression in synovial fibroblasts. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:718–726. doi: 10.1172/JCI19899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shlopov BV, Gumanovskaya ML, Hasty KA. Autocrine regulation of collagenase 3 (matrix metalloproteinase 13) during osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:195–205. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200001)43:1<195::AID-ANR24>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song RH, Tortorella MD, Malfait AM, Alston JT, Yang Z, Arner EC, Griggs DW. Aggrecan degradation in human articular cartilage explants is mediated by both ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:575–585. doi: 10.1002/art.22334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton LA, Underhill TM, Beier F. MAP kinases in chondrocyte differentiation. Dev Biol. 2003;263:165–175. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00321-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada I, Mihara M, Suzawa M, Ohtake F, Kobayashi S, Igarashi M, Youn MY, Takeyama K, Nakamura T, Mezaki Y, Takezawa S, Yogiashi Y, Kitagawa H, Yamada G, Takada S, Minami Y, Shibuya H, Matsumoto K, Kato S. A histone lysine methyltransferase activated by non-canonical Wnt signalling suppresses PPAR-gamma transactivation. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1273–1285. doi: 10.1038/ncb1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takebe K, Nishiyama T, Hayashi S, Hashimoto S, Fujishiro T, Kanzaki N, Kawakita K, Iwasa K, Kuroda R, Kurosaka M. Regulation of p38 MAPK phosphorylation inhibits chondrocyte apoptosis in response to heat stress or mechanical stress. Int J Mol Med. 2011;27:329–335. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2010.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamamura Y, Otani T, Kanatani N, Koyama E, Kitagaki J, Komori T, Yamada Y, Costantini F, Wakisaka S, Pacifici M, Iwamoto M, Enomoto-Iwamoto M. Developmental regulation of Wnt/beta-catenin signals is required for growth plate assembly, cartilage integrity, and endochondral ossification. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19185–19195. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414275200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavella S, Raffo P, Tacchetti C, Cancedda C, Castagnola P. N-CAM and N-cadherin expression during in vitro chondrogenesis. Exp Cell Res. 1994;215:354–362. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thalhamer T, McGrath MA, Harnett MM. MAPKs and their relevance to arthritis and inflammation. Rheumatology. 2008;47:409–414. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton TM, Pedraza-Alva G, Deng B, Wood CD, Aronshtam A, Clements JL, Sabio G, Davis RJ, Matthews DE, Doble B, Rincon M. Phosphorylation by p38 MAPK as an alternative pathway for GSK3beta inactivation. Science. 2008;320:667–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1156037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibbles LA, Woodgett JR. The stress-activated protein kinase pathways. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;55:1230–1254. doi: 10.1007/s000180050369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topol L, Jiang X, Choi H, Garrett-Beal L, Carolan PJ, Yang Y. Wnt-5a inhibits the canonical wnt pathway by promoting GSK-3-independent beta-catenin degradation. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:899–908. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyama T, Lee HC, Koga H, Wands JR, Kim M. Noncanonical Wnt11 inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation and migration. Mol Cancer Res. 2010;8:254–265. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tufan AC, Daumer KM, DeLise AM, Tuan RS. AP-1 transcription factor complex is a target of signals from both WnT-7a and N-cadherin-dependent cell-cell adhesion complex during the regulation of limb mesenchymal chondrogenesis. Exp Cell Res. 2002;273:197–203. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tufan AC, Tuan RS. Wnt regulation of Limb mesenchymal chondrogenesis is accompanied by altered N-cadherin-related functions. FASEB J. 2001;15:1436–1438. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0784fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuli R, Tuli S, Nandi S, Huang X, Manner PA, Hozack WJ, Danielson KG, Hall DJ, Tuan RS. Transforming growth factor-beta-mediated chondrogenesis of human mesenchymal progenitor cells involves N-cadherin and mitogen-activated protein kinase and Wnt signaling cross-talk. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41227–41236. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305312200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von der Mark K, Kirsch T, Nerlich A, Kuss A, Weseloh G, Glückert K, Stöss H. Type X collagen synthesis in human osteoarthritic cartilage. Indication of chondrocyte hypertrophy. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:806–811. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H, de Caestecker MP, Yamada Y. Transcriptional cross-talk between Smad, ERK1/2, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways regulates transforming growth factor-beta-induced aggrecan gene expression in chondrogenic ATDC5 cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:14466–14473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005724200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westendorf JJ, Kahler RA, Schroeder TM. Wnt signaling in osteoblasts and bone diseases. Gene. 2004;341:19–39. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong GT, Gavin BJ, McMahon AP. Differential transformation of mammary epithelial cells by Wnt genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6278–6286. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.6278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Tu X, Joeng KS, Hilton MJ, Williams DA, Long F. Rac1 activation controls nuclear localization of beta-catenin during canonical Wnt signaling. Cell. 2008;133:340–353. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Wang W, Ludeman M, Cheng K, Hayami T, Lotz JC, Kapila S. Chondrogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells in three-dimensional alginate gels. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14:667–680. doi: 10.1089/tea.2007.0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Topol L, Lee H, Wu J. Wnt5a and Wnt5b exhibit distinct activities in coordinating chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation. Development. 2003;130:1003–1015. doi: 10.1242/dev.00324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuasa T, Otani T, Koike T, Iwamoto M, Enomoto-Iwamoto M. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling stimulates matrix catabolic genes and activity in articular chondrocytes: its possible role in joint degeneration. Lab Invest. 2008;88:264–274. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun MS, Kim SE, Jeon SH, Lee JS, Choi KY. Both ERK and Wnt/beta-catenin pathways are involved in Wnt3a-induced proliferation. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:313–322. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhen X, Wei L, Wu Q, Zhang Y, Chen Q. Mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 mediates regulation of chondrocyte differentiation by parathyroid hormone. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:4879–4885. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004990200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M, Chen M, Zuscik M, Wu Q, Wang YJ, Rosier RN, O’Keefe RJ, Chen D. Inhibition of beta-catenin signaling in articular chondrocytes results in articular cartilage destruction. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2053–2064. doi: 10.1002/art.23614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]