Abstract

Background and Aims:

Skill of a successful endotracheal intubation needs to be acquired by training and attaining several competencies simultaneously. It becomes more challenging when we have to deliver the key concepts in a limited period of time. The medium fidelity simulator is a valuable tool of training for such scenarios. For this purpose we aim to compare the efficacy of structured training in endotracheal intubation between real life simulation and the conventional teaching method.

Materials and Methods:

The year 4 medical students had their attachment in anaesthesia for a period of 6 months from Jun — Dec 2009 were randomly divided into Group (Gp) A who had conventional teaching and Group B who were taught by four simulated sessions of endotracheal intubation. Performance of both the groups was observed by a person blinded to the study against a checklist on a 7 point rating scale in anaesthetized patient.

Results:

Total 57 students, 29 in Gp A and 28 in Gp B were rotated in the anaesthesia during the study period. Evaluation of the individual component tasks revealed that simulated group achieved a significant difference in the scoring for laryngoscope and intubation technique. (P = 0.026, 0.012) The comparison of overall competence again showed that the 64.3% of student in Gp B achieved an excellent score in comparison to Gp A in which only 41.4% achieved excellent. (P = 0.049). Similarly the lesser number of students in Gp B (14.3%) require remediation as compared to the Gp A, in which the requirement was 40% (P=0.04).

Conclusion:

We conclude that all essential skills components of tracheal intubation in correct flow and sequence are acquired more efficiently by real life simulated training.

Keywords: Endotracheal intubation, in situ simulation, real life, undergraduate

Introduction

The endotracheal intubation is a skill required not only for the routine anesthesia provision, but also as a requirement for Advanced Cardiac Life Support certification.[1] The skill delivered in isolation does not relate to real-life scenarios that are complex and multidimensional. Definitely, the teaching strategy needs to be focused on several competencies simultaneously. The traditional approach of teaching is not suitable for undergraduate or paramedic students where they have got limited time, exposure, and concern of patient's safety. The real-life medium fidelity simulation is a valuable tool for training the multidimensional aspects of endotracheal intubation with the facility of having repetitive practice sessions. The technique can also be utilized for the assessment of competence[2] without compromising the patient's safety.

The aim of this study was to compare the efficacy between two teaching strategies that is the real-life in situ simulation and conventional teaching as a tool for acquisition of tracheal intubation.

Materials and Methods

Phase four level medical students having an attachment in anesthesiology for a period of 2 weeks were enrolled in the study. The ethical approval and informed consent were also taken from the participants. All students were randomly allocated into either Group A or Group B. Randomization was done using sealed envelope technique at the start of rotation.

Group A went into routine training for tracheal intubation which included the text book reading, random hands on training in Operation Theater or practice on mannequin, while the Group B had four simulated training sessions for tracheal intubation in addition. To start up with the process [Figure 1] both groups had a scheduled tutorial on airway management on the 2nd day of their attachment. The tutorial was conducted by a faculty routinely assigned by the rotation coordinator (not participating in the study). For Group B, four sessions of simulation training were done by one of the investigators on a standard format of instruction. Out of four dedicated sessions, three were done in the 1st week, and the fourth one was done in the last week of their training. All sessions were conducted in an operating room creating a real life or in situ simulation with a fully functional anesthesia workstation, operating table, airway management equipment, along with the monitoring of vital signs. Tracheal intubation training was done on an anatomical model mannequin with well-defined airway anatomy. The duration of each simulated instruction included 10-15 min of verbal instruction and demonstration. After that each student was given one turn of the supervised practice session of 5-10 min and this was followed by a feedback time.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of methodology

The single anesthetist (consultant grade) blinded to the study assessed the performance of component tasks required for the intubation in both the groups. All assessments were done against a checklist on an anesthetized American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA)-I patient with no anticipated difficulty in intubation as estimated by the functional assessment of airway. The checklist already had details of component tasks need to be fulfilled during the stepwise approach of tracheal intubation. The tasks included were the equipment check, positioning, preintubation airway management, laryngoscopy technique, intubation and confirmation of tube placement. All of these tasks were evaluated on 7-point rating scores. The score between 0 and 1 was unsatisfactory, between 2 and 3 was marginal while the scores between 4-5 and 6-7 were given the status of acceptable and excellent. The scores were then compared between the two groups. Overall passing scores between the groups were also compared and based on their performance in terms of achieved scores the need for remediation for a number of students in Group A and B was also compared.

Statistical analysis

Power calculation was performed using NCSS-power analysis and sample size software-version 11.0.4 (East, Kaysville, Utah, 84037, USA). The primary outcome variable for the study was competence scores for the individual tasks (above five considered effective). A power analysis indicated that a sample size of 29 in Group A and 28 in Group B achieved 81% power to detect difference between the group proportions of 0.35. The proportion in group one is assumed to be 0.40 under the null hypothesis. Data were double entered and analyzed using SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) for performance rating in the two groups at the end of rotation. Percentages/frequencies were generated for qualitative variable and compared by Chi-square test. P < 0.05 was taken as significant. For quantitative variables mean (±standard deviation) was computed and the comparison between the two groups of students was made by using t-test.

Results

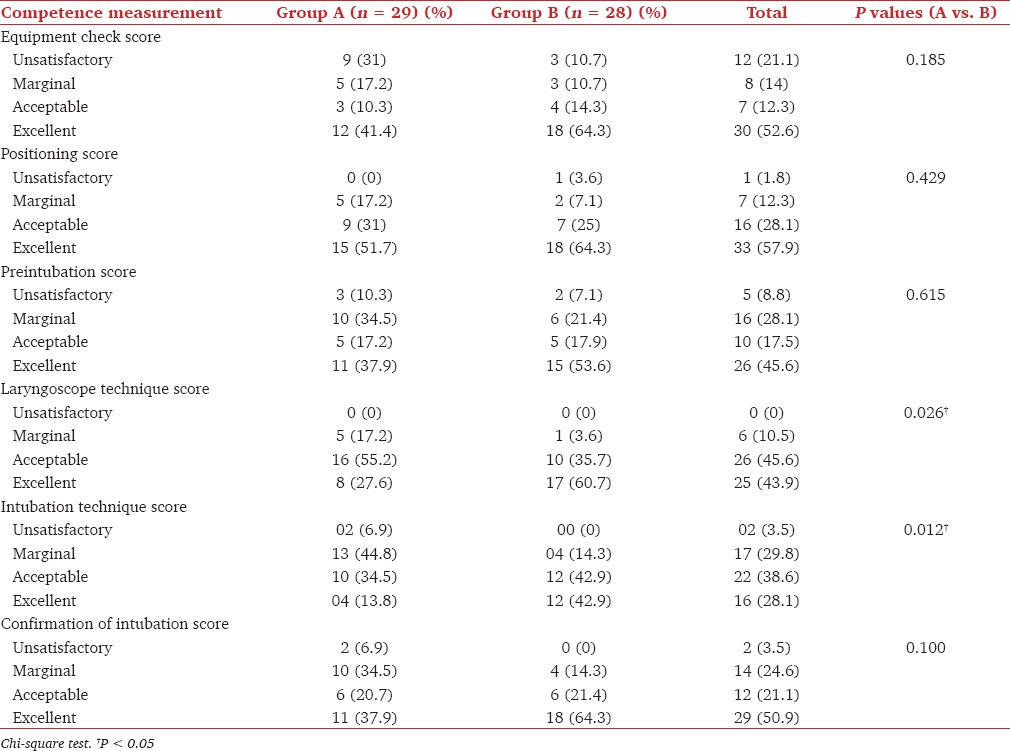

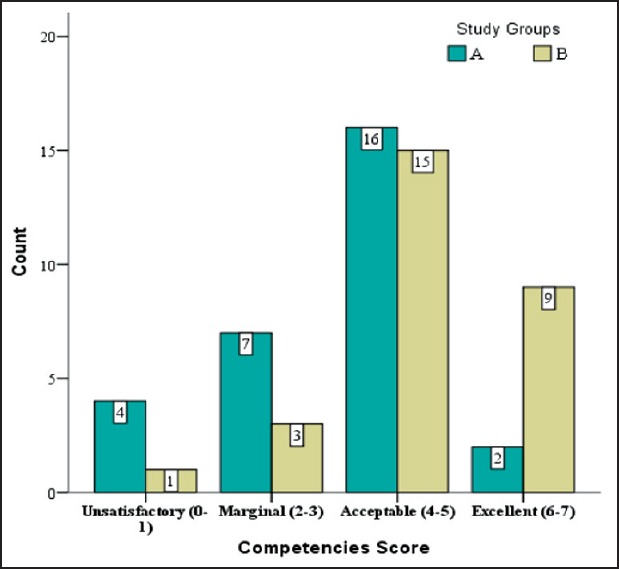

Total of 57 students participated in the study. Group A had 29 students while the Group B had 28 students. Evaluation of the individual component tasks revealed that both groups exhibited statistically insignificant scoring as compared to each other in the tasks such as equipment checking (P = 0.185), positioning (P = 0.429), preintubation (P = 0.615), and confirmation of intubation (P = 0.10). The scoring for laryngoscope and intubation techniques were significantly better in Group B, the simulated group. As mentioned in Table 1, P values for these score were 0.026 and 0.012, respectively. Comparison of overall competence score related to the tracheal intubation revealed a significant difference in between the groups as shown in Figure 2. About 64.3% of students in Group B achieved an excellent score in comparison to Group A, where only two students that is 41.4% had an excellent score (P = 0.049). Similarly, the evaluation of the need for remediation revealed that greater number of students in Group A (40%) needed remediation when compared to the simulation group in which the requirement was only 14.3%. P = 0.04.

Table 1.

Comparison of competency score between the groups

Figure 2.

Comparison of competency score between the groups (P: 0.049)

Discussion

Endotracheal intubation is a complex technical skill with a number of component tasks that is cognition, integration and automation need to be fulfilled simultaneously.[3] The task becomes extremely difficult for the novice trainees in a real-life where they have to perform it on an actual patient with simultaneous attention to cardio-respiratory status. With the current trend in the reduction of medical training hours or short duration of the attachment, this condition may get further compromised.[4] Simulation is a safe nonthreatening, nonurgent method of providing repetitive practice to acquire and achieve proficiency in such skills.[5] Our results showed a definite role of simulation in teaching the technical skills related to tracheal intubation in students who had simulated sessions hence proving it as an effective teaching strategy.[6] The strategy was also helpful in orienting the students with the equipment and theater environment which is very important for them to perform endotracheal intubation. The findings of our study were inconsistent with the study done by Hall et al. In their prospective randomized controlled trial conducted on paramedic students, they identified an insignificant difference for an endotracheal intubation performance between simulation versus the students who had training on live human subjects.[7] The methodology they used involved a 10 h of simulated session or 15 number of intubations on actual patients. Before that both groups were involved 20 h didactic/video training and 10 h of mannequin training of intubation as a part of their curriculum. This actually reflects on the importance of simulation training in situations where time is a constraint. In our department undergraduates have their anesthesia attachment for a period of 2 weeks where they share the opportunities to learn intubation skills with the residents. The opportunities also get limited by their academic schedule, as they have to acquire exposure of preoperative anesthesia clinic, pain clinic, and labor room, etc. Simulation provides an opportunity to learn and practice repetitively at any available time. The overall progress in the equipment check score, positioning score and preintubation score of our study was not significant, where most of the student scored acceptable or excellent irrespective of the groups. It may be related to the fact that our simulation scenario was more helpful in teaching the technical skills when compared to the scores which have got the element of nontechnical skills.

As discussed above the time constraint of a short undergraduate rotation and patient's availability makes scheduled assessment of intubation skills uncertain.[8] For this reason, we propose that our simulation model is a safe tool for the assessment of competence skills required for this purpose. We are also recommending this model for the assessment of individual component task required for tracheal intubation. Though we cannot comment on the validity of this tool as it was not our objective, but we have identified a number of following observations that indirectly confirms its validity in the evaluation process. Our results showed that in the simulation group, the number of students scoring excellent in preintubation tasks, performance of laryngoscope and intubation as well as confirmation of intubation was much higher. The number of participants having marginal and unsatisfactory performance of intubation was greater in the conventional group. Similarly, the incidence of failed intubation was more in the conventional group.

Conclusion

We conclude that all the essential skills required for tracheal intubation in correct flow and sequence are acquired more efficiently by real-life simulation training.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Zirkle M, Blum R, Raemer DB, Healy G, Roberson DW. Teaching emergency airway management using medical simulation: A pilot program. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:495–500. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000157834.69121.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byrne AJ, Greaves JD. Assessment instruments used during anaesthetic simulation: Review of published studies. Br J Anaesth. 2001;86:445–50. doi: 10.1093/bja/86.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reznick RK, MacRae H. Teaching surgical skills — Changes in the wind. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2664–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra054785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper GM, McClure JH. Anaesthesia chapter from Saving mothers’ lives; reviewing maternal deaths to make pregnancy safer. Br J Anaesth. 2008;100:17–22. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper JB, Taqueti VR. A brief history of the development of mannequin simulators for clinical education and training. Postgrad Med J. 2008;84:563–70. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.009886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang CH. Medical simulation is needed in anesthesia training to achieve patient's safety. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2013;64:204–11. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2013.64.3.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall RE, Plant JR, Bands CJ, Wall AR, Kang J, Hall CA. Human patient simulation is effective for teaching paramedic students endotracheal intubation. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:850–5. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Owen H, Plummer JL. Improving learning of a clinical skill: The first year's experience of teaching endotracheal intubation in a clinical simulation facility. Med Educ. 2002;36:635–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]