Abstract

Background:

Oropharyngeal dysphagia following stroke enhances the risk of dehydration, malnutrition, aspiration pneumonia, persistent disablement, and even death. Screening of dysphagia has been shown to positively change health outcomes. The aim of the present study was to systematically introduce the published swallowing screening methods in patients with stroke and their appropriateness for detecting swallowing disorders following stroke with an emphasis on the methodological quality of their research studies.

Materials and Methods:

A computerized search through the Medline (PubMed), Embase, Scopus, and Google Scholar; databases from 1990 through 20 July 2013 was performed. In addition, the related citations and reference lists of the selected articles were considered.

Results:

A total of 264 papers were retrieved and 19 articles finally met inclusion criteria. Sixty-eight percent of included papers did not have a sufficient quality and only six articles were scored as having evidence level ‘I’ and were reported descriptively. The most prevalent bias in the included studies was probably a kind of spectrum bias that could lead to select just a subgroup of admitted stroke patients. The screening tests’ sensitivities ranged from 47 to 100%, while their specificities ranged from about 63 to 100%. Strengths and limitations of each test have been discussed.

Conclusion:

We ultimately found four simple, valid, reliable, sensitive, and specific tests for screening swallowing disorders in the almost all acute alert stroke patients. Further validation and reliability assessing of screening tests need to follow a very accurate and well-established method in a large sample of the almost all acute alert stroke patients admitted to the hospitals.

Keywords: Swallowing, stroke, screening tests, systemic review, valid, reliable

INTRODUCTION

Oropharyngeal swallowing dysfunction is one of the most significant problems after stroke.[1] The reported prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia following stroke varies between 22 and 65%,[2,3] depending on different sampling methods,[4] methods and timing of assessment,[5,6] and definition of dysphagia. Persistent oropharyngeal dysphagia is a marker of poor prognosis of stroke patients.[6] It can enhance the risk of dehydration,[3] malnutrition,[3] aspiration pneumonia,[3,7] and persistent disablement.[3,8,9] Aspiration pneumonia is one of the most life-threatening consequences of dysphagia in stroke.[7] Patients with dysphagia are 3-11 times more likely to develop pneumonia than stroke patients with reserved swallowing ability, depending on severity of dysphagia and presence or absence of aspiration.[7] Also, mortality risk is higher in stroke patients with dysphagia.[3] It is shown that about 20% of stroke victims will die from aspiration pneumonia in the 1st year post onset.[10]

Dysphagia screening methods and dysphagia assessment procedures (clinical and/or instrumented)[11] are usually used with different purposes. Clinical and instrumental assessment methods are administrated to find the underlying anatomic and/or physiologic abnormalities leading to swallowing problems and finally to design the appropriate treatment plan.[12] But swallowing screening methods, according to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA),[13] are the pass/fail procedures to identify individuals who may need a comprehensive assessment of swallowing function. Screening of swallowing abnormalities, the first step in an appropriate management plan,[14] has been shown to reduce risk of developing pneumonia,[7,15] percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) insertion rates, and mortality in patients with stroke.[7] Hinchey et al.,[15] showed that systematic use of a formal dysphagia screening protocol can decrease pneumonia rates from 5.4 to 2.4%. So management dysphagia guidelines, developed by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario (HSFO), emphasize that all patients with acute stroke have to be kept ‘nil by mouth’ (NPO) including medications until their swallowing safety has been established. According to these guidelines, swallowing ability of all stroke patients should be screened as soon as they are awake and alert.[16] Nowadays, most acute care settings use a kind of dysphagia screening protocol, especially in the developed countries. But differences in the accuracy of the used screening protocols and specialists’ training levels can impact on the results. Some patients may be consequently underdiagnosed and the risk of developing aspiration pneumonia may be enhanced. On the other hand, some patients may be kept NPO for a period of time without any swallowing dysfunction. So, the implementation of a simple, valid, and reliable screening test that is sensitive and specific to the swallowing problems[11] in the acute care settings is necessary to reduce stroke-related costs and some of the resulting preventable consequences.[7] However, there are very delicate biases impacting on the authenticity of a test, even though its psychometric values seem very reasonable. Considering the quality of the research study[11] is therefore suggested as an important factor when selecting a screening test. So the aim of the present study was to systematically introduce the published swallowing screening methods in patients with stroke and their appropriateness for the detection of swallowing disorders following stroke with an emphasis on the methodological quality of their research studies. The following question was formulated: What are the psychometric and feasibility properties of the available highly qualified screening tests to detect swallowing disorders following stroke? Although there are some other published systematic reviews in this regard,[6,14,17] the present study was focused on the methodological quality of the research studies and some common biases like spectrum and verification biases. In fact this review was interested in the well-qualified screening tests that can be administrated in the almost all acute alert stroke patients by the frontline professionals who have the earliest contact with the patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature search

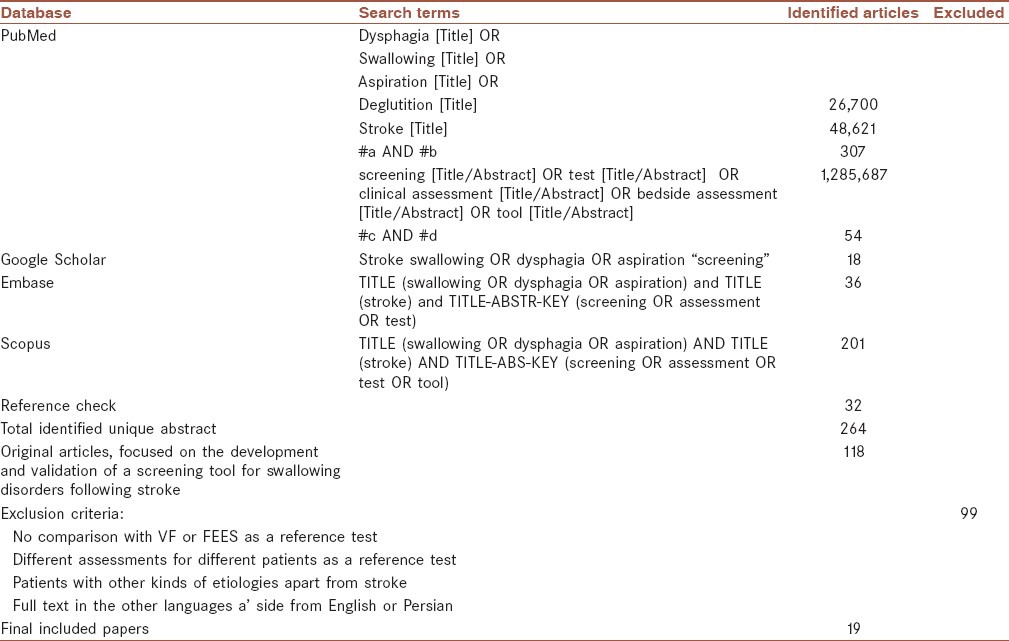

A computerized search through the Medline (PubMed), Embase, Scopus, and Google Scholar databases from 1990 through 20 July 2013 was performed. It was limited to published articles on humans. In addition, the related citations and reference lists of the selected articles were considered. Table 1 shows used terms and a flowchart for identified abstracts.

Table 1.

Search terms and a flowchart for identified abstracts

Study selection and eligibility criteria

After elimination of duplicate ones, the outcome of search strategy was 264 papers. From all retrieved sources, just original studies focused on the development and validation of a screening tool for swallowing disorders following stroke were included. Therefore, reviews, editorials, or letters and those articles that were unrelated to our mentioned purpose were not reviewed. Then the abstracts (or full text in doubtful cases) of included articles (118 papers) were reviewed based on the exclusion criteria. Those articles that had studied patients with other kinds of etiologies apart from diagnosed stroke were excluded. Besides, this review was interested in clinical screening tests that were compared with a videofluoroscopic (VF) assessment (or modified barium swallow) or fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES). So, articles that had used a clinical assessment, speech, and language pathologists’ judgments about swallowing function, or patients’ clinical features and outcomes as a gold standard were excluded. Also there were some studies that had used varied criteria and tests as a reference test. In other words, authors had not used a unique test for all their patients. These articles were excluded, because different tests will lead to different results. Also only publications with full text in English and Persian were reviewed. These criteria are presented in Table 1 in detail.

Study quality of every included article (19 papers) was assessed using the 12-step criteria adapted from Jaeschke et al., 1994.[18,19] This form considered following three broad issues for appraising a diagnostic test:

Are the results of the study valid?

What are the results?

Will the results help me and my patient/population?

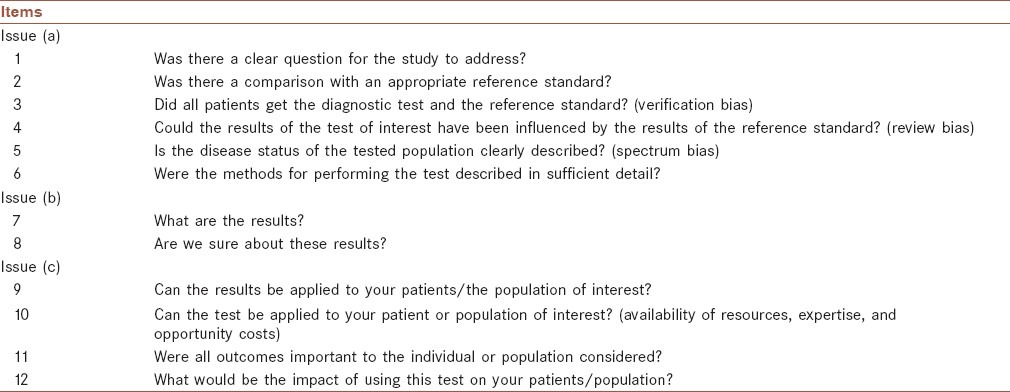

Table 2 shows a description of these criteria in brief with a little modification in some questions’ grammar. Most questions were answered with a ‘Yes’, ‘No’, or ‘Can’t tell” except questions 7, 8, and 12 that should be described. The first two questions were “screening questions” and could be answered fast. Even if the answer to one of them was “No” or “can’t tell”, it was not worth continuing to the remaining questions. It seemed we could not be sure about an article's results (Question 8) if the reference test and the index test were not carried out blindly (Question 4), and/or all patients did not get the index and the reference test regardless of the results of the index test (Question 3), and/or there was a kind of spectrum bias in selection of stroke patients leading to choose only a subgroup of stroke patients (Question 5), and/or there were other confidence limits in the methodology. In addition, a diagnostic test could not be useful for patients and could not help to identify swallowing disorders following stroke (Questions 11 and 12), unless we could be sure about its results at least approximately (Question 8), and its psychometric features (e.g., sensitivity and specificity) were acceptable. Based on these criteria, the evidence level of every article was categorized as level I or II:

Table 2.

The 12-steps criteria adapted from Jaeschke et al., (1994) in brief

Blinded comparison (Question 4) with no verification and spectrum biases (Questions 3 and 5 answered Yes or at least Can’t tell), and with reported or at least calculable results (Question 7).

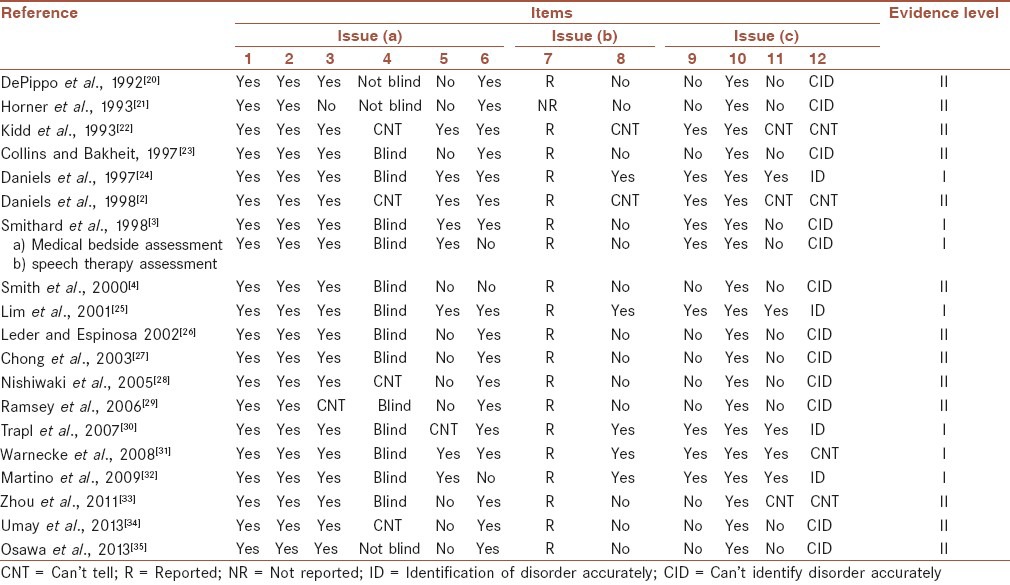

Studies which did not have at least one of the four above conditions. Table 3 shows the results of articles’ quality assessment.

Table 3.

The results of articles’ quality assessment

Data extraction and abstraction

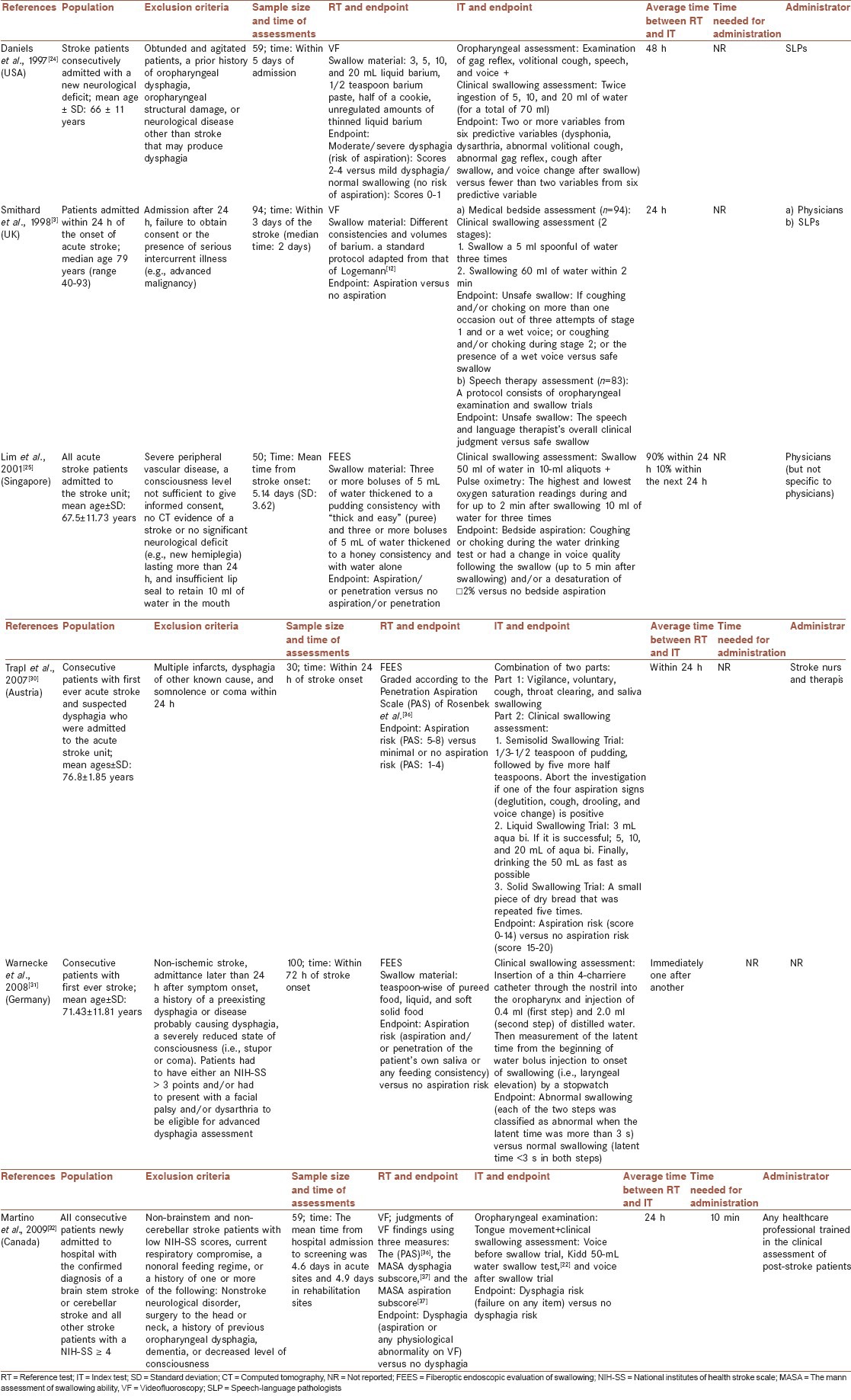

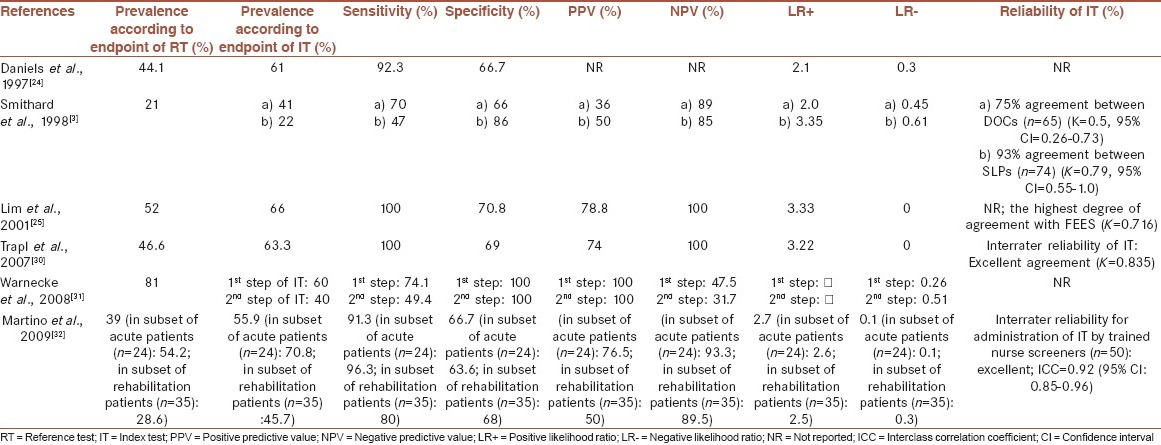

Tables 4 and 5 show some data extracted from the studies with evidence level I. This information can be divided into two categories: Information about characteristics of the studied population and information about the used index and reference tests.

Table 4.

Properties of articles with evidence level I

Table 5.

Psychometric features of final selected screening tests

RESULTS

As mentioned above, 19 articles met our inclusion criteria[2,3,4,20,24,25,30,31,32] and level of evidence of 32% of them (six articles)[3,24,25,30,31,32] was I according to the performed quality assessment.

Included studies

VF evaluation had been carried out as a “gold standard” in most studies (68.5%).[2,3,4,20,21,22,23,24,28,29,32,33,35] All other included studies had used FEES as a reference test.[25,26,27,30,31,34]

A variety of tests were used to screen swallowing disorders in bedside. In eight of included studies (42%), screening protocols consisted of a combination of a sensorimotor examination and clinical swallowing assessment.[2,3,22,24,26,30,32,33] There was a large variety in tasks assessed in sensorimotor examinations. In these studies, clinical swallowing assessments usually included water swallowing in different volumes.[3,22,24,26,32,33] Different consistencies had been used as swallow materials just in two articles.[7,32] Four studies (21%)[20,28,31,35] used just a kind of water swallow test as a screening tool and one[23] involved measurement of oxygen desaturation alone. Five papers described a combination of pulse oximetry and trial swallows.[4,25,27,29,34] Finally, Horner et al.,[21] examined some clinical features to assess risk of aspiration, such as age, lesion site, abnormal gag, volitional cough, and voice.

About one-third of included papers did not have or did not report a blind design,[2,20,21,22,28,34,35] and so their evidence levels were scored II. But this kind of bias was not so popular in the more recent years.

The most prevalent bias in the included studies probably was a kind of spectrum bias that could lead to selection of a subgroup of admitted stroke patients and so could influence on the test's generalizability. Eleven papers[4,20,21,23,26,27,28,29,33,34,35] had such bias to some extent. Some studies included those stroke patients who referred for swallowing evaluations[23,26,27,28,33] and no all consecutive stroke patients admitted to the hospital. Also, some other researchers[4,29] excluded patients with probably more severe disabilities because of some problems with sitting balance and poor medical condition.

Studies with evidence level I

Tables 4 and 5 show some properties and psychometric features of tests that met quality criteria. A half of these studies used VF[3,24,32] and the other half used FEES[25,30,31] as a reference test. Daniels et al.,[24] and Lim et al.,[25] described their used volumes and consistencies of swallow materials in the reference standard in detail. Smithard et al.,[3] reported the using of an adaptation of Logemann standard protocol for videofluoroscopy.[12] But other researchers[30,31,32] did not present a description of their used protocol for the reference test in sufficient detail.

All final selected tests[3,24,25,30,31,32] consisted of a clinical swallowing assessment part. Trapl et al.,[30] used a variety of consistencies (semisolid, liquid, and solid) in their clinical swallowing trials; and according to the points in different consistencies, they could suggest a special diet for each patient.[30] All other researchers[3,24,25,31,32] just assessed patients’ ability to swallow liquids (different volumes of water). Used liquid volumes ranging from 2.4[31] to 88 ml[30] in different selected tests. Most researchers divided liquid volumes into smaller aliquots that gradually progress to larger volumes, and discontinued their test if a patient developed some signs of swallowing disorders or discomfort during each step.[3,24,30,32] The test proposed by Trapl et al.,[30] however, consisted of a timed swallow test of a relatively large amount of water (50 ml) that should be administered cautiously.

Most tests had been assessed for their accuracies to identify only aspiration and/or penetration.[3,25,26,31] But Daniels et al.,[24] and Martino et al.,[32] paid attention to dysphagia as a global term that may include any abnormal physiology of oropharyngeal swallowing, regardless of the presence or absence of aspiration.[12] The reported endpoints by Daniels et al.,[24] Martino et al.,[32] and Trapl et al.,[30] for the index tests included at least one variable that was exclusively associated with oral phase of swallowing. But other tests[3,25,31] did not include any indicator of the oral phase and so could not detect disorders in patients with a predominantly impaired oral phase of swallowing and a relatively intact pharyngeal phase.[31]

Except Daniels et al.,[24] all other researchers[3,25,30,31,32] administered the index and the reference test within 24 h.

There has been a trend towards developing the screening tests that could be administrated by various healthcare specialists and not just speech-language pathologists (SLPs) or physicians.[30,32]

The screening tests’ sensitivities ranged from 47 to 100%, while their specificities ranged from about 63 to 100%. The test proposed by Lim et al.,[25] achieved the highest sensitivity and specificity (100 and 70.8%, respectively). Fifty percent of studies did not report the tests’ reliability.[24,25,31] Interrater reliability varied from moderate to excellent agreement in the remaining screening tests.[3,30,32] [Table 5].

DISCUSSION

This review showed that there are a large variety of screening tests for swallowing disorders following stroke that are different in types, methods, endpoints, and their psychometric values. There were many differences in selected population, time of the test administration, and other aspects of methodology. In this systematic review, the methodological quality of every included article was assessed using criteria adapted from Jaeschke et al., 1994[18,19] and was scored according to our predefined values as either having evidence level I or II. Bases on our relatively strict judgment, 68% of included papers did not have a sufficient quality. It emphasizes the importance of considering methodological limitations of studies, and of improving study design standards in such studies. A blind design for validation of diagnostic tests, as an instance, is vital. Because if the reference test and the index test are not interpreted independently, the results of tests may be influenced by each other. This kind of bias was not so popular in the more recently validated screening tests. But the results of many reviewed studies,[4,20,21,23,26,27,28,29,33,34,35] according to our quality assessment, had been influenced by a sort of spectrum bias. We were hoping to find the tests that can be administered in almost all patients with acute alert stroke admitted to hospital newly. When patients are selected based on lots of inclusion and exclusion criteria, the selected patients may represent only a subgroup of stroke patients (spectrum bias) and no all alert patients admitted to hospital with acute stroke. Although some criteria such as consciousness and being able to follow some simple instruction are necessary for swallowing assessment, but some other features like receptive dysphasia or inability to sit upright without support must not deprive patients of assessing of swallowing mechanism. This manner of selecting patients can have biased the assessed population toward patients with mild and moderate strokes. Also selecting patients from those referred to SLPs to assess swallowing[23,26,27,28,33] or from those having some features indicating possible dysphagia,[20,28,34,35] may lead to select patients who more likely suffer from dysphagia or have more obvious swallowing disorders. A very accurate screening test may be not necessary for identification of such disorder.[18,19] In addition, silent aspiration is a serious concern in acute stroke[2] and patients with this kind of aspiration may not refer to speech-language therapist for evaluation of swallowing function due to absence of clinical symptoms. The whole spectrum of patients with acute stroke, therefore, was not included in these studies. So in this review, those articles with the least selection on admitted patients met quality criteria and are reported in detail.

A half of six tests with evidence level I had used VF as a reference test. Although VF evaluation is almost accepted as a gold standard for assessing swallowing disorders,[38] some limitations are reported for it. Interrater reliability of VF is often poor[39,40] and it assesses the patients’ ability in swallowing of small amounts of foods and in an optimal situation that does not usually reflect the natural situation of patient's feeding.[41] These limitations may impact on the calculated validities of the index tests. So Smithard et al.,[3] recommended that the use of VF as a gold standard in the validation studies should be critically explored in the further studies.

As mentioned above, just a half of the high qualified studies[3,24,25] provided a description of their used protocol for the reference test in detail. Different protocols will examine patients’ swallowing mechanism in different levels and with different accuracies. It may be one of the reasons of various reported prevalence of swallowing disorders following stroke. Making a description of the parts of performed ‘gold standard’, therefore, can help readers to make a more accurate judgment about the study.

Only Trapl et al.,[30] used different consistencies in the swallowing trails. Although it may increase needed time and equipment for the test administration, but can lead to a more accurate picture of patients’ swallowing abilities. This screening test[30] also consisted of a swallowing trial of a relatively large amount of water. Large volumes of liquids may introduce a high risk of aspiration and airway obstruction to the patients.[42] Although the authors[30] warned about cautious administration of this part, but the administration of a “screening test” must not be dangerous for patients.

Although swallowing disorders in the pharyngeal phase are common in patients with stroke,[7,12] but dysphagia is described as any kind of difficulty moving food from mouth to stomach.[12] Oropharyngeal dysphagia screening tests therefore should consider both oral and pharyngeal phases of swallowing process. The screening test reported by Daniels et al.,[24] Martino et al.,[32] and Trapl et al.,[30] included at least one indicator of the oral phase.

Since the severity of dysphagia changes during acute phase after stroke rapidly, a 24-h interval between administration of the reference and index tests seems short enough to be sure that the patient's condition will not change between the two tests significantly.[17] The average time between the two tests was more than 24 h only in the study of Daniels et al.[24]

SLPs are in short supply in many hospitals.[11] So screening tests that can be conducted by various healthcare professionals may accelerate the screening process of newly admitted acute stroke patients.[11] Screening tests developed by Lim et al.,[25] Trapl et al.,[30] and Martino et al.,[32] could be administrated by a variety of healthcare specialists.

Regarding serious consequences of swallowing disorders, it seems a valid clinical examination for detecting such disorders after stroke must have a high sensitivity. Such a screening test will miss just a few patients with swallowing disorders.[32] Since the main purpose of administration of a swallowing screening, according to ASHA[13] is identification of patients who need to refer for a more comprehensive swallowing assessment and not designing treatment plan, a moderate-high specificity may be enough. In such circumstances, some patients without dysphagia may be referred to speech-language therapists for assessment and before starting of any kind of treatment, will be probably identified as patients with safe and intact swallowing abilities.[32] In this review, we could find four well-qualified screening tests with high sensitivity.[24,25,30,32] Specificities of these tests[24,25,30,32] were almost near to each other and ranged from 66.7 to 70.8%. The test proposed by Lim et al.,[25] that was a combination of water swallow and pulse oximetry, achieved the highest sensitivity and specificity (100 and 70.8%, respectively).

Systematic reviews are prone to the selection bias, especially if they were limited to studies in English. It means a systematic review is not probably included of all available studies about a specific subject.[17] This kind of bias was likely the most significant limitation of the present systematic review. In addition, our search strategy was restricted to a few databases and did not include a manual search of available books in swallowing disorders or stroke. We cannot assert that we searched all available articles on swallowing screening following stroke. Also we focused on tests that compared with VF or FEES. It resulted in the exclusion of some popular tests like the Burk dysphagia screening test[43] because of its used reference test. In addition, we were strict about spectrum bias in the quality appraisal assessment in order to be able to generalize the results to the almost all admissions with acute stroke to the hospitals. Some other articles, therefore, were assessed as having an evidence level II and so were not reported in detail.

CONCLUSION

We were hoping to find simple, valid, reliable, sensitive, and specific tests for screening swallowing disorders in almost all acute alert stroke patients. It seems the four reported high qualified screening tests including Oral Pharyngeal and Clinical Swallowing Examination,[24] Bedside Aspiration Test,[25] The Gugging Swallowing Screen,[30] and The Toronto Bedside Swallowing Screening Test (TOR-BSST),[32] have almost all of these characteristics. Further researches are needed to investigate the effects of the administration of these tests upon stroke patients’ outcomes. Also, further validation and reliability assessing of screening tools need to follow a very accurate and well-established method in a large sample of almost all stroke patients admitted to the hospitals. Only such screening tools could ultimately lead to the reduction of the consequences of swallowing disorders in the patients with stroke.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

SJ contributed in the conception of the work, design of the work, analysis and interpretation of data, conducting the study, revising the draft, approval of the final version of the manuscript, and agreed for all aspects of the work. MP contributed in the conception of the work, design of the work, interpretation of data, revising the draft, approval of the final version of the manuscript, and agreed for all aspects of the work.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.McLaren S. Eating disabilities following stroke. Br J Community Health Nurs. 1997;2:9–19. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daniels SK, Brailey K, Priestly DH, Herrington LR, Weisberg LA, Foundas AL. Aspiration in patients with acute stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79:14–9. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(98)90200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smithard DG, O’neill PA, Park C, England R, Renwick DS, Wyatt R, et al. North West Dysphagia Group. Can bedside assessment reliably exclude aspiration following acute stroke? Age Ageing. 1998;27:99–106. doi: 10.1093/ageing/27.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith HA, Lee SH, O’Neill PA, Connolly MJ. The combination of bedside swallowing assessment and oxygen saturation monitoring of swallowing in acute stroke: A safe and humane screening tool. Age Ageing. 2000;29:495–9. doi: 10.1093/ageing/29.6.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perry L. Screening swallowing function of patients with acute stroke. Part one: Identification, implementation and initial evaluation of a screening tool for use by nurses. J Clin Nurs. 2001;10:463–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2001.00501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramsey DJ, Smithard DG, Kalra L. Early assessments of dysphagia and aspiration risk in acute stroke patients. Stroke. 2003;34:1252–7. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000066309.06490.B8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martino R, Foley N, Bhogal S, Diamant N, Speechley M, Teasell R. Dysphagia after stroke incidence, diagnosis, and pulmonary complications. Stroke. 2005;36:2756–63. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000190056.76543.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smithard DG, O’Neill PA, England RE, Park CL, Wyatt R, Martin DF, et al. The natural history of dysphagia following a stroke. Dysphagia. 1997;12:188–93. doi: 10.1007/PL00009535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramsey DJ, Smithard DG. Assessment and management of dysphagia. Hosp Med. 2004;65:274–9. doi: 10.12968/hosp.2004.65.5.13702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scmidt EV, Smirnov VE, Ryabova VS. Results of the seven-year prospective study of stroke patients. Stroke. 1988;19:942–9. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.8.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donovan NJ, Daniels SK, Edmiaston J, Weinhardt J, Summers D, Mitchell PH. American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Nursing and Stroke Council. Dysphagia Screening: State of the art: Invitational conference proceeding from the State-of-the-Art Nursing Symposium, International Stroke Conference 2012. Stroke. 2013;44:e24–31. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182877f57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Logemann JA. 1st ed. San Diego: College-Hill Press; 1983. Evaluation and treatment of swallowing disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Association AS-L-H. Preferred practice patterns for the profession of speech-language pathology. 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perry L, Love CP. Screening for dysphagia and aspiration in acute stroke: A systematic review. Dysphagia. 2001;16:7–18. doi: 10.1007/pl00021290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hinchey JA, Shephard T, Furie K, Smith D, Wang D, Tonn S Stroke Practice Improvement Network Investigators. Formal dysphagia screening protocols prevent pneumonia. Stroke. 2005;36:1972–6. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000177529.86868.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fedorak A, Finestone HM, Little J, MacGarvie D, Martino R. Improving recognition and management of dysphagia in acute stroke. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bours GJ, Speyer R, Lemmens J, Limburg M, de Wit R. Bedside screening tests vs. videofluoroscopy or fibreoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing to detect dysphagia in patients with neurological disorders: Systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65:477–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaeschke R, Guyatt G, Sackett D. Users Guides to the medical literature: How to use an article about a diagnostic test. B. What are the results and will they help me in caring for my patients? The Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1994;271:703–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.9.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaeschke R, Guyatt G, Sackett DL Group E-BMW. Users’ guides to the medical literature: III. How to use an article about a diagnostic test: A Are the results of the study valid? JAMA. 1994;271:389–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.5.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DePippo KL, Holas MA, Reding MJ. Validation of the 3-oz water swallow test for aspiration following stroke. Arch Neurol. 1992;49:1259–61. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1992.00530360057018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horner J, Brazer SR, Massey EW. Aspiration in bilateral stroke patients: A validation study. Neurology. 1993;43:430. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.2.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kidd D, Lawson J, Nesbitt R, MacMahon J. Aspiration in acute stroke: A clinical study with videofluoroscopy. QJM. 1993;86:825–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins MJ, Bakheit AM. Does pulse oximetry reliably detect aspiration in dysphagic stroke patients? Stroke. 1997;28:1773–5. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.9.1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daniels SK, McAdam CP, Brailey K, Foundas AL. Clinical assessment of swallowing and prediction of dysphagia severity. Am J Speech-Lang Pathol. 1997;6:17. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lim SH, Lieu PK, Phua SY, Seshadri R, Venketasubramanian N, Lee SH, et al. Accuracy of bedside clinical methods compared with fiberoptic endoscopic examination of swallowing (FEES) in determining the risk of aspiration in acute stroke patients. Dysphagia. 2001;16:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s004550000038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leder SB, Espinosa JF. Aspiration risk after acute stroke: Comparison of clinical examination and fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing. Dysphagia. 2002;17:214–8. doi: 10.1007/s00455-002-0054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chong MS, Lieu PK, Sitoh YY, Meng YY, Leow LP. Bedside clinical methods useful as screening test for aspiration in elderly patients with recent and previous strokes. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2003;32:790–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nishiwaki K, Tsuji T, Liu M, Hase K, Tanaka N, Fujiwara T. Identification of a simple screening tool for dysphagia in patients with stroke using factor analysis of multiple dysphagia variables. J Rehabil Med. 2005;37:247–51. doi: 10.1080/16501970510026999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramsey DJ, Smithard DG, Kalra L. Can pulse oximetry or a bedside swallowing assessment be used to detect aspiration after stroke? Stroke. 2006;37:2984–8. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000248758.32627.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trapl M, Enderle P, Nowotny M, Teuschl Y, Matz K, Dachenhausen A, et al. Dysphagia bedside screening for acute-stroke patients: The Gugging Swallowing Screen. Stroke. 2007;38:2948–52. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.483933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warnecke T, Teismann I, Meimann W, Oelenberg S, Zimmermann J, Krämer C, et al. Assessment of aspiration risk in acute ischaemic stroke–evaluation of the simple swallowing provocation test. J Neurol Neurosurgery Psychiatry. 2008;79:312–4. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.134551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martino R, Silver F, Teasell R, Bayley M, Nicholson G, Streiner DL, et al. The toronto bedside swallowing screening test (TOR-BSST): Development and validation of a dysphagia screening tool for patients with stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:555–61. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.510370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou Z, Salle J, Daviet J, Stuit A, Nguyen C. Combined approach in bedside assessment of aspiration risk post stroke: PASS. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2011;47:441–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Umay EK, Unlu E, Saylam GK, Cakci A, Korkmaz H. Evaluation of dysphagia in early stroke patients by bedside, endoscopic, and electrophysiological methods. Dysphagia. 2013;28:395–403. doi: 10.1007/s00455-013-9447-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Osawa A, Maeshima S, Tanahashi N. Water-swallowing test: Screening for aspiration in stroke patients. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;35:276–81. doi: 10.1159/000348683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenbek JC, Robbins JA, Roecker EB, Coyle JL, Wood JL. A penetration-aspiration scale. Dysphagia. 1996;11:93–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00417897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mann G. MASA: The Mann assessment of swallowing ability. Cengage Brain.com. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rao N, Brady S, Chaudhuri G, Donzelli J, Wesling M. Gold-standard? Analysis of the videofluoroscopic and fiberoptic endoscopic swallow examinations. J Appl Res. 2003;3:89–96. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scott A, Perry A, Bench J. A study of interrater reliability when using videofluoroscopy as an assessment of swallowing. Dysphagia. 1998;13:223–7. doi: 10.1007/PL00009576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stoeckli SJ, Huisman TA, Seifert B, Martin–Harris BJ. Interrater reliability of videofluoroscopic swallow evaluation. Dysphagia. 2003;18:53–7. doi: 10.1007/s00455-002-0085-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wright F. A swallow assessment clinic-why and how. Radiology. 1991;8:55–7. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Logemann JA, Veis S, Colangelo L. A screening procedure for oropharyngeal dysphagia. Dysphagia. 1999;14:44–51. doi: 10.1007/PL00009583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DePippo KL, Holas MA, Reding MJ. The Burke dysphagia screening test: Validation of its use in patients with stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;75:1284–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]