Abstract

This paper employs a unique method of imputing the legal status of Mexican immigrants in the 1996-1999 and 2001-2003 panels of the Survey of Income and Program Participation to provide new evidence of the role of legal authorization in the U.S. on workers’ wages. Using growth curve techniques, we estimate wage trajectories for four groups: documented Mexican immigrants, undocumented Mexican immigrants, U.S-born Mexican Americans, and native non-Latino whites. Our estimates reveal a 17 percent wage disparity between documented and undocumented Mexican immigrant men, and a 9 percent documented-undocumented wage disparity for Mexican immigrant women. We also find that in comparison to authorized Mexicans, undocumented Mexican immigrants have lower returns to human capital and slower wage growth.

Keywords: Legal Status, Immigration, Mexicans, Wages, Discrimination, Gender

Over the past 20 years, two apparently contradictory changes have been taking place in the U.S. labor market: the quantity and quality of jobs available to low-skill workers have steadily declined, and the number of low-skill immigrants entering the country in search of employment has steadily increased (Waldinger and Lichter 2003). The increase in the number of immigrants from Mexico has been especially notable. Given the large size of this stream and the fact that economic circumstances have become less favorable for lower-skilled workers, understanding how Mexican immigrants fare in the labor market is of considerable interest. Research by sociologists and economists on labor market outcomes for low-skill immigrants, including Mexicans, attests to the interest of social scientists in this question. Yet one potentially critical influence on the labor market outcomes of this group has been rarely examined: legal status. By considering the influence of legal status, this paper provides a more complete understanding of the factors shaping Mexican immigrants’ earnings in U.S. labor markets.

As governmental efforts to prevent employers from hiring unauthorized immigrants have increased, and social services and political privileges for undocumented immigrants have been rolled back, the importance of legal status for immigrants’ outcomes is likely to have increased. In order to make clear comparisons between ethnic groups and examine trends in immigrants’ earnings over time, it is therefore crucial to disaggregate immigrants by legal status (Massey and Bartley 2005). Failure to do so is to risk distorting the realities faced by Mexican immigrants in the labor market or attributing the effects of legal status to other factors, such as cultural differences between ethnic groups or declines in immigrants’ unobservable skills over time. Further, other factors influencing the earnings of Mexican immigrants may interact with legal status in ways that are not yet understood. For instance, returns to human capital have been shown to be lower for low-skill Mexican immigrants than for other low-skill workers (Hall and Farkas 2008). It is possible that this finding is driven by the inability of unauthorized workers, who make up a much larger proportion of immigrants from Mexico than from most other sending countries, to translate human capital into higher earnings. It is therefore necessary to consider the role of legal status when evaluating the effects of human capital and other worker characteristics that may be correlated with legal status.

This paper employs a unique method of imputing the legal status of Mexican immigrants included in the 1996-1999 and 2001-2003 panels of the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP). We then use this information to provide a more complete understanding of earnings disparities faced by Mexican immigrants in the low-wage labor market. In particular, we focus on two broad questions. First, does legal status matter for the wages of low-skill Mexican immigrants, and if so, does the high proportion of Mexican immigrants who are unauthorized explain the wage disadvantage that has been documented in previous studies? Second, are the returns to human capital similar for documented and undocumented Mexican immigrants?

Background

Legal Status and Earnings Disparities for Mexican Immigrants

It is well known that recently arrived immigrants have lower earnings, on average, than native-born workers with similar educational levels. Labor market disadvantages that are common among foreign-born workers include employers’ lower valuation of both work experience and educational credentials obtained outside the U.S., lack of English language skills, and lack of knowledge about the U.S. labor market. There is a substantial research literature on the earnings “assimilation” patterns of immigrant workers that debates the extent to which immigrants’ earnings catch up with those of natives over time spent in the U.S. (Borjas 1985; Chiswick 1978; Schoeni 1997). While it is expected that there will be disparities in earnings between foreign- and native-born workers, Mexican immigrants stand out for their particularly low earnings. The median earnings of Mexican and Central American immigrants who worked full-time, full-year in 2003 were only $20,840, compared with $38,486 among European immigrants, $40,297 among Asian immigrants, and $36,784 among native-born workers (U.S. Census Bureau 2004). Poverty rates are also disproportionately high among Mexican and Central American immigrants, with nearly 25% living in poverty (compared with only 10%, 12%, and 11% of European immigrants, Asian immigrants, and the U.S.-born population, respectively) (Census Bureau 2004).

The low average educational attainment of Mexican immigrants undoubtedly contributes to their low earnings. Over 40% of Mexican immigrants over age 25 have completed less than a ninth grade education (Census Bureau 2004), a low level of education that is extremely rare among the U.S.-born population (at only 3.7%). Schoeni (1997) estimated that this disparity in education is responsible for about one-third of the wage gap between male native workers and Mexican immigrant workers, but found that a substantial wage differential remained unexplained even after controlling education. For most other immigrant groups studied, by contrast, Schoeni found little or no unexplained earnings disadvantage after controlling for education and age. He proposed the high proportion of undocumented immigrants in the Mexican foreign-born population as one possible explanation for this difference.

This speculation appears to be well-founded. Both popular accounts and the academic literature have portrayed undocumented immigrants as especially vulnerable to discrimination and exploitation by employers (Massey 1987; Rivera-Batiz 1999). Employing undocumented immigrants makes it easier for employers to skirt regulations designed to protect workers, such as the minimum wage and overtime pay. Lack of documentation also weakens workers’ bargaining position relative to employers, potentially resulting in lower wages. However, empirical verification of the labor market disadvantages associated with undocumented status has been limited. Donato and Massey (1993) demonstrated that the passage of the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) in 1986, which introduced new penalties for establishments employing undocumented immigrants, substantially increased the wage penalties associated with undocumented status. Therefore, the findings of studies based solely on data collected prior to 1986 can no longer be relied upon to indicate how undocumented immigrants are currently faring. The relatively small number of post-IRCA studies have found evidence of substantial earnings penalties associated with undocumented status, on the order of 14-24% for Mexican immigrants (Donato and Massey 1993; Kossoudji and Cobb-Clark 2002; Rivera-Batiz 1999).

Post-IRCA research on the effect of legal status on immigrants’ earnings has been limited, primarily due to data constraints. The sensitive nature of questions about legal status precludes them from being included in the nationally representative surveys that form the basis for most studies of labor market outcomes. Thus, most existing studies have relied on smaller, non-nationally representative samples. Donato and Massey (1993) utilized unique data, collected on both sides of the border, on migrants from 13 Mexican communities. They found substantial earnings penalties associated with being undocumented, but only after the passage of IRCA. Donato et al. (2008), using a later, expanded version of the same dataset, found that legal status not only affected earnings but was also related to a greater likelihood of employment in the informal sector. The results also showed that women's situation relative to men had deteriorated following IRCA, increasing the importance of considering potential gender differences in the effects of legal status. Most other previous studies have relied primarily on one data source – the Legalized Population Survey (LPS) (Kossoudji and Cobb-Clark 2002; Powers and Seltzer 1998; Powers, Seltzer and Shi 1998; Rivera-Batiz 1999). This survey was conducted among a sample of immigrants who had applied for legalization under IRCA. The immigrants were surveyed twice, once prior to becoming legalized (in 1988) and once after legalization (in 1992). Researchers have taken advantage of this unusual longitudinal data to attempt to estimate the causal effect of the change in legal status on earnings.

We believe that our use of SIPP data presents significant advantages over the LPS. Although the LPS data are unique in that they directly identify undocumented immigrants, their usefulness is limited by the fact that they do not contain a comparison group of workers who did not experience a change in legal status. Rivera-Batiz (1999) addresses this problem by comparing Mexican immigrant workers included in the LPS with similar Mexican immigrant workers from the 1990 Census, who are assumed to be predominantly legal – a problematic assumption given the high proportion of Mexican immigrants who are undocumented. Kossoudji and Cobb-Clark (2002) use Hispanic immigrant and native men from the NLSY as a comparison group. While in this case the comparison sample is not as potentially contaminated by containing a substantial share of workers who are actually undocumented, it differs from the undocumented sample on many characteristics other than legal status, such as nativity, length of residence in the U.S., and specific Hispanic ethnicity. By contrast, our study uses a single nationally representative data source to identify both documented and undocumented Mexican immigrants, as well as Mexican American and white native comparison groups. We are therefore able to more effectively estimate the unique influence of legal status on workers’ wages.

Returns to Human Capital

In addition to providing an improved estimate of the effect of undocumented status on earnings, we explore the extent to which returns to human capital vary by legal status. Hall and Farkas (2008) analyzed differences by race and nativity in earnings returns to education among low-skill workers. They found that of all the race/nativity groups studied, Hispanic immigrants were the only group for whom education did not significantly raise earnings, and that returns to education were particularly low for Mexican and Central American immigrants. We suggest that the high proportion of undocumented workers among low-skill Mexican immigrants may contribute to their uniquely low returns to education.

Theories of labor market segmentation, recently summarized by Hudson (2007), posit that the economy contains two distinct sets of jobs: those at the “core,” which offer stability, good working conditions, higher pay, and prospects for advancement; and those at the “periphery,” which tend to be low-paying, “dead-end” jobs with few prospects for improvements in earnings, regardless of human capital. Although the existence of such a clear demarcation has been challenged on empirical grounds, it is widely recognized that low-skill immigrant workers tend to be concentrated disproportionately in jobs with many “peripheral” characteristics. While Hudson (2007) found that many workers who start out in peripheral jobs eventually move on to better jobs, this may not be as true for undocumented workers, whose lack of legal authorization to work in the U.S. presents a barrier to switching employers. The lack of internal opportunities for advancement in peripheral jobs, coupled with greater difficulty in moving to better jobs, may combine to depress wages among undocumented workers.

Even disregarding theories of labor market segmentation, any barrier to switching employers should have the effect of depressing earnings growth: Topel and Ward (1988) demonstrate that at least 1/3 of early-career earnings growth is attributable to workers moving to better-paying jobs, rather than to internal raises or promotions. To the extent that their legal status restricts undocumented workers’ ability to seek better jobs, their human capital is likely to be rewarded less highly in the labor market, even in the absence of discrimination by employers.

We test this possibility by exploring differences between undocumented Mexican immigrants and other groups (including both documented Mexican immigrants and native white and Mexican-American workers) in wage returns to education and work experience.

Legal Status and Gender

Finally, we recognize the possibility that the processes influencing the labor market outcomes of Mexican immigrants differ by gender. Mexican migration is known to be a gendered process. Traditionally, men have been more likely to be primary labor migrants, while women have been more likely to accompany them or follow them several years later as dependents (Donato, Wagner and Patterson 2008). Women's relatively later arrival within the migration stream, their greater likelihood of joining family members rather than migrating alone, and their greater responsibility for children are all factors that may make their earnings trajectories following migration different from those of men. Occupational and industrial segregation by gender, race, and nativity is another factor that may play different roles for male and female migrants. While occupational segregation of Latino immigrants is a factor that affects both men and women (see Catanzarite's (2001) work on “brown-collar” occupations), jobs are further segregated by gender, with immigrant Latina women shuttled into a particularly narrow range of jobs (Myers and Cranford 1998). Because of these and other potential gender differences in the effect of migration-related factors on earnings, we model both the effect of legal status and the returns to human capital variables separately for men and women.

Data and Methods

Study Sample

This paper analyzes monthly wage data from the 1996-1999 and 2001-2003 panels of the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP). SIPP is a panel study focusing on tracking U.S. workers’ employment and public program experiences. The SIPP design draws a nationally representative sample of U.S. households and interviews each household member every four months for three (2001-2003) to four (1996-1999) years. At each interview, respondents are asked wave-specific topical questions and a set of core questions that cover the reference months and preceding three months. Thus, in the 1996 panel, for a respondent who completes all 12 interviews, there are 48 months of observation. SIPP provides translators for respondents with poor English skills.

SIPP is uniquely suited for this study for several reasons. First, these data contain a wealth of information on wages, work experience, and educational attainment. Second, the combined samples of the 1996 and 2001 panels include a large number of Mexican immigrants and Mexican American natives. Third, unlike other large, nationally representative data sources, SIPP includes key variables, such as immigrant visa status and participation in public welfare programs, that can be used to assess the legality of Mexican immigrants.

Since we are interesting in the wage trajectories of low-skill workers, we limit our sample to workers between 18 and 60 whose highest level of educational attainment is no more than a high school degree (or its equivalent). We restrict the sample to men and women who self-identify as either native-born non-Hispanic white or of Mexican-descent (native or foreign born). Using the ancestry data in SIPP, native Mexican Americans (second or higher generation) refer to U.S.-born individuals who identify as “Mexican,” “Mexican-American,” or “Chicano.” Mexican immigrants, by contrast, are individuals who were born in Mexico, but migrated and are currently living in the U.S. Nativity data comes from a set of topical questions asked during wave 2 (months 5 to 8); and inclusion in our sample is thus restricted to those who completed the “migration” module. We segment individual longitudinal records into a series of person-months, one person-month for each month of data collected.

Study Variables

The dependent variable in this analysis is respondents’ current wage rate. Our measure of wage rate corresponds to the rate of pay of the respondent's primary job. For workers who are employed on an hourly basis, wage rates are reported by respondents. Among workers who report a pay unit other than “per hour,” we estimate wage rates based on monthly personal earned income from the respondent's primary job and the number of hours worked in a given month at that job. Since this procedure of estimating wage rates occasionally results in extreme values, we set lower and upper bounds of $1.00 and $250.00 per hour, respectively.1

We include two measure of individual human capital in our models: educational attainment and work experience. Educational attainment is measured as years of schooling completed (up to 12 years). Full employment histories are not available in SIPP; therefore, we use “potential” work experience, defined as age (in years) minus educational attainment plus 6 [age-(education+6)], as our measure of time in the labor market. Unfortunately, language ability is unavailable in the 1996 SIPP panel, and the combined panels sample is necessary for sufficient sample sizes.2 However, research has shown that English skills have little effect on wages after controlling for educational attainment and time in the U.S. (Bleakley and Chin 2004). Thus, for models specific to immigrants, we include a term for age at arrival to the U.S., which in conjunction with work experience (described above) controls for length of time in the country. To account for differences in occupation, we include terms indicating employment in one of seven Bureau of Labor Statistics-defined aggregated occupational sectors (based on the 1990 classification scheme): managerial and professional; technical, sales, and administrative; service; farming, forestry, and fishing; production, craft, and repairers; and operatives and laborers.

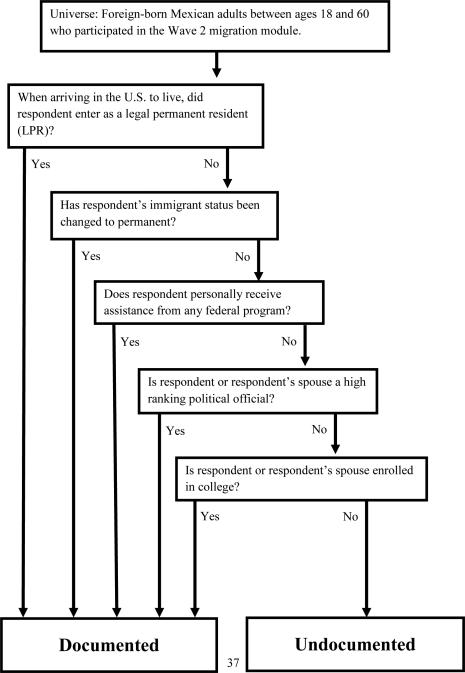

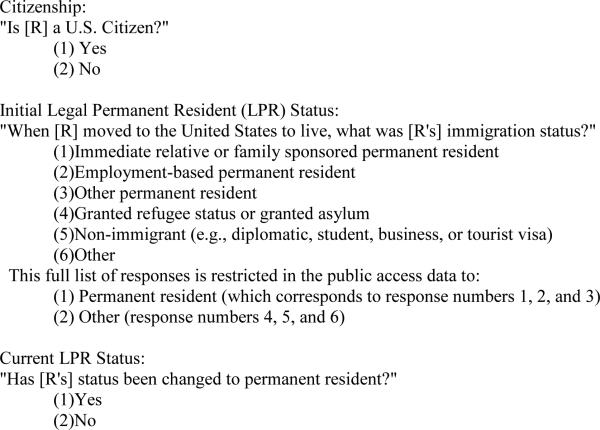

Inferring Legal Status

The key independent variable in our study is legal status. As with most surveys, undocumented status is not measured directly in SIPP. However, with knowledge of Mexican migration patterns derived from earlier research and data from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), it is possible to use information available in SIPP to infer legal status for Mexican immigrants. (See Appendix Figure 1 for a schematic presentation of the imputation strategy). SIPP gathers information on whether sampled immigrants are naturalized citizens or legal permanent residents (LPRs) (see Appendix 2 for survey questions). We classify such immigrants as legal. If an immigrant “personally”, as opposed to “dependently” (i.e., via a child's eligibility), receives federal welfare benefits (e.g., Food Stamps, Medicaid, SSI, TANF), for which undocumented immigrants are not eligible, he or she is also classified as legal. Remaining immigrants are either undocumented or have visas falling into one of several categories: refugees and asylees, students and exchange visitors, tourist and business travelers, temporary workers, and diplomats and other political representatives (U.S. Department of Homeland Security 2007). Tourists and other short-term visitors are not sampled by SIPP and, historically, very few Mexicans have been granted asylum in the U.S. Those enrolled in school are excluded from a sample, but to be certain that we are not mis-categorizing the legal spouses of immigrants on student visas, we consider those with an immigrant spouse enrolled in college full-time (student visas are contingent on full-time enrollment) as legal. To account for those admitted as diplomats, we deem Mexican foreigners that report being or are married to those employed as high ranking public officials to be in the country legally. The only group of temporary migrants that we are unable to directly infer is temporary workers. However, authorized temporary workers form a small minority of Mexicans in the U.S. (see U.S. Department of Homeland Security 2007). Nonetheless, readers should keep in mind that the group we refer to as “undocumented” may include a small proportion of authorized temporary workers.

Methods

To best utilize the longitudinal nature of the data and to model both initial wages and wage growth aspects of workers’ wage trajectories, we employ hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) techniques (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002), where both the intercepts and the slopes are a function of time-invariant person specific characteristics. More specifically, we estimate random-coefficient growth curve models (Greene 2000) for a pooled sample of Mexican immigrants, and separately for Mexican documented immigrants, Mexican undocumented immigrants, and native Mexican Americans and non-Latino whites. Our pooled Mexican immigrant growth curve models are specified as follows:

where t refers to chronological month and j represents individuals. Each value of t corresponds to the number of months elapsed since first interview. There are, depending on the panel, 48 (1996 panel) or 36 (2001 panel) possible values of t. Ln(wages)tj represents logged hourly wages of respondent j at month t. β0 is the intercept and β1 is the wage growth rate, which are both a function of person-specific characteristics legal, education, experience, arrival, Z, and panel. Legalj is a dummy variable representing the legal status of Mexican immigrant j (documented=1; undocumented=0); educationj refers to years of schooling for person j; experiencej represents labor market experience for person j; arrivalj indicates age at arrival to the U.S. for person j; Zj is a vector of occupational dummy variables (with “managerial and professional” serving as the referent); panelj is a dummy variable indicating the SIPP panel (1996 or 2001); μj are unobserved differences that affect wages; and rtj is a stochastic error term.

These models allow both the intercepts and slopes to be correlated (tau), and for autoregressive error terms to adjust for serial correlation and heterogeneity in the variance within individuals (rho). To account for the non-random sample loss of poor households (Bavier 2002), both the descriptive and inferential parts of this analysis are adjusted using the person weights provided by SIPP.

Results

Table 1 shows average wage rates in six month intervals, between the first and 36th month, for the pooled SIPP panels (1996 and 2001), separately for men and women workers belonging to each of the four low-skill analysis groups – documented Mexican immigrants, undocumented Mexican immigrants, Mexican-Americans and non-Latino white natives. Although there are some irregular movements in these mean wages, almost all groups show an upward trend in wage rates over time. Thus among low-skill males, the hourly wages of documented Mexican immigrants rise from $9.82 to $10.88 over the 36 month span; those of undocumented Mexican immigrants rise from $8.27 to $9.36 over this period; those of Mexican-Americans rise from $10.74 to $11.62; and those of non-Latino white natives rise from $12.98 to $14.49.

Table 1.

Mean Wages (in $ per hour) by Observation Month

| Month |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | 12 | 18 | 24 | 30 | 36 | |

| Men | |||||||

| Documented Mexican Immigrants | $9.82 | $9.63 | $10.24 | $10.24 | $10.32 | $10.94 | $10.88 |

| Undocumented Mexican Immigrants | $8.27 | $8.09 | $8.57 | $9.00 | $9.42 | $9.57 | $9.36 |

| Mexican-Americans (Natives) | $10.74 | $10.62 | $10.59 | $11.18 | $11.09 | $11.37 | $11.62 |

| Non-Latino White Natives | $12.98 | $12.90 | $13.25 | $13.66 | $14.07 | $14.28 | $14.49 |

| Women | |||||||

| Documented Mexican Immigrants | $7.63 | $7.80 | $7.80 | $7.91 | $7.78 | $8.02 | $8.18 |

| Undocumented Mexican Immigrants | $7.08 | $7.26 | $7.05 | $6.68 | $6.98 | $7.30 | $7.07 |

| Mexican-Americans (Natives) | $8.65 | $8.65 | $8.85 | $9.14 | $9.26 | $9.78 | $9.80 |

| Non-Latino White Natives | $9.69 | $9.81 | $10.16 | $10.44 | $10.66 | $10.87 | $11.01 |

For low-skill women, the hourly wages of documented Mexican immigrants rise from $7.63 to $8.18, those of Mexican-Americans rise from $8.65 to $9.80, and those of non-Latino white Natives rise from $9.69 to $11.01. The exception is female undocumented Mexican immigrants – their hourly wages average $7.08 in the first month of the panel, and $7.07 in the 36th month. This group has the lowest starting wages, and no wage growth, over the observed duration.

Table 2 shows the means for the exogenous variables used in the wage trajectory regressions, separately for men and women in each of the four ethnic/legal groups. Not surprisingly, we find that low-skill native Mexican-Americans and whites have higher educational levels than Mexican immigrants. Among men, natives are much more likely than immigrants to hold managerial and professional, and technical, sales, and administrative jobs, whereas immigrants are more likely to be employed in service and farming, forestry and fishing. For women, natives are also more likely than immigrants to be employed in managerial, and professional, and technical, sales, and administrative jobs while immigrants have higher representation in service, farming, forestry and fishing, production, craft, and repairer, and operative and laborer occupations. Despite these differences between native and immigrant workers, documented and undocumented Mexican immigrants appear quite alike: both groups have similar levels of education and ages at arrivals, and are similarly distributed across the occupational categories; legal Mexican immigrants do, however, have about 6 more years of experience in the labor market than do undocumented Mexican immigrants.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Exogenous Variables, by Sex and Ethnic/Legal Group

| Men |

Women |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doc. Mexican Immigrants | Undoc. Mexican Immigrants | Mexican-Americans | Non-Latino White Natives | Doc. Mexican Immigrants | Undoc. Mexican Immigrants | Mexican-Americans | Non-Latino White Natives | |

| Labor market experience | 22.27 | 16.71 | 17.55 | 21.12 | 24.57 | 17.75 | 19.31 | 22.89 |

| Education (years of schooling) | 7.90 | 7.99 | 10.73 | 11.63 | 7.86 | 8.32 | 10.87 | 11.74 |

| Age at arrival to the U.S. | 19.87 | 21.03 | -- | -- | 20.95 | 22.50 | -- | -- |

| Occupation: | ||||||||

| Managerial and Professional | .03 | .0 2 | .0 6 | .0 9 | .0 3 | .0 1 | .1 0 | .1 5 |

| Technical, Sales, and Administrative |

.05 | .05 | .17 | .15 | .17 | .18 | .48 | .47 |

| Service | .16 | .15 | .13 | .10 | .39 | .29 | .24 | .20 |

| Farming, Forestry, and Fishing | .15 | .16 | .06 | .03 | .08 | .08 | .01 | .01 |

| Production, Craft, and Repairers | .24 | .26 | .23 | .29 | .06 | .08 | .03 | .03 |

| Operatives and Laborers | .37 | .35 | .35 | .34 | .27 | .36 | .13 | .13 |

| N of individuals | 1,1 49 | 375 | 828 | 9,9 17 | 732 | 171 | 742 | 9,3 23 |

| N of person-months | 32,598 | 8,817 | 22,932 | 294,518 | 16,410 | 3,413 | 17,829 | 258,364 |

Legal Status and Wage Trajectories

Men

Table 3 shows growth curve regressions for the logged wages of low-skill Mexican immigrant men. Our presentation of the growth curve models shows the intercept or starting wage effects in the upper half of the table and the slope or wage growth rate effects in the lower half. Thus, for example, the legal status effect in the “intercepts” panel refers to the impact of being documented on wages at the start of each panel period (one beginning in 1996 and the other in 2001), and legal status in the “slopes” panel shows the monthly wage return to being documented (i.e., the interaction between legal status and time). Wages have been log-transformed in our regression models, which allows for marginal effects to be interpreted as percent change in wages resulting from a one-unit change in predictor variables. To ease the presentation of the results, all coefficients in Table 3 and subsequent regression analyses have been multiplied by a factor of 100. The first column of Table 3 shows a model in which legal status is the only predictor; the second column adds labor market experience, education, and age at arrival to the U.S. to the regression, and the third column also adds occupation.

Table 3.

Growth Curve Regression Coefficients Predicting Logged Wages for Mexican Immigrant Men

| (1) |

(2) |

(3) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | β | t | |

| Intercepts (Starting wage)† | ||||||

| Constant | 206.79 | (85.60) *** | 171.34 | (32.40) *** | 176.22 | (29.18) *** |

| Legal status | 17.31 | (6.56) *** | 7.42 | (2.75) ** | 7.50 | (2.84) ** |

| Labor market experience | 1.63 | (10.91) *** | 1.58 | (10.75) *** | ||

| Education (years of schooling) | 3.46 | (9.14) *** | 3.30 | (8.85) *** | ||

| Age (in years) at arrival to the U.S. | −.92 | (−5.77) *** | −.86 | (−5.53) *** | ||

| Occupation: a | ||||||

| Technical, Sales, and Administrative | −.99 | (−.28) | ||||

| Service | −12.24 | (−3.71) *** | ||||

| Farming, Forestry, and Fishing | −7.16 | (−2.15) * | ||||

| Production, Craft, and Repairers | 5.76 | (1.80) + | ||||

| Operatives and Laborers | −6.02 | (−1.95) * | ||||

| Slopes (Monthly wage growth)† | ||||||

| Time (in months) | .51 | (4.90) *** | .89 | (3.80) *** | 1.36 | (5.13) *** |

| Legal status | .12 | (1.07) | −.05 | (−.44) | −.05 | (−.39) |

| Labor market experience | −.01 | (−1.93) * | −.01 | (−1.87) + | ||

| Education (years of schooling) | −.02 | (−1.50) | −.03 | (−1.57) | ||

| Age at arrival to the U.S. | .00 | (.13) | .00 | (.09) | ||

| Occupation: a | ||||||

| Technical, Sales, and Administrative | −.45 | (−2.94) ** | ||||

| Service | −.23 | (−1.66) + | ||||

| Farming, Forestry, and Fishing | −.57 | (−4.04) *** | ||||

| Production, Craft, and Repairers | −.73 | (−5.55) *** | ||||

| Operatives and Laborers | −.45 | (−3.45) *** | ||||

| −2 log likelihood | −1662.7 | −1809.1 | −2052.6 | |||

Notes: N= 41,415 person-months

p < .001

p < .01

p < .05

p < .10 (two-taile d tests); coefficients and standard errors multiplied by 100; models are weighted and include control for SIPP survey panel (1996 or 2001)

“Professional and managerial occupations” are the reference category.

The first column shows that documented male workers average significantly higher starting wages than those who are undocumented. The gross wage premium associated with being a legal immigrant is 17.3 percent. In our sample of Mexican immigrant men, wages grow at an average rate of 0.5 percent per month. However there is no significant effect of legal status on the rate of wage growth during these panel periods, indicating that documented and undocumented immigrants’ wages increase at about the same pace.

In the second column of this table, we test whether the wage disparity between documented and undocumented Mexican immigrants is due to differences in human capital. The results show that, as expected, starting wages are affected positively by labor market experience and education, and negatively by age at arrival. The negative slope effect for experience indicates that the positive return to education (in the intercept equation) is less positive for workers with more experience. Education and age at arrival do not significantly influence wage growth – at least within our relatively short period of observation. With these variables controlled, the wage advantage for being legal is reduced by more than half (57%), but the legal status effect on starting wages is still large, positive, and highly significant, and suggests that net of human capital, documented Mexican immigrants hold a 7.4% wage premium over their undocumented peers.

Labor segmentation theories posit that one reason unauthorized immigrant workers’ wages are lower than legal immigrants is that they are permanently consigned to jobs in the “periphery” of the labor market. While the results in the final column loosely conform to the segmentation prediction that peripheral occupations have lower starting wages and wage growth than professionals and managers, controlling for occupation does not attenuate the wage advantage of being documented.

Women

Table 4 repeats these calculations for low-skill female Mexican immigrants. The first column indicates that a significant wage differential between documented and undocumented female workers of about 8.6 percent. The coefficient of legal status in the slope equation indicates that that documented Mexican women's wage grow slightly faster than undocumented workers, but not significantly so.

Table 4.

Growth Curve Regression Coefficients Predicting Logged Wages for Mexican Immigrant Women

| (1) |

(2) |

(3) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | β | t | |

| Intercepts (Starting wage)† | ||||||

| Constant | 192.64 | (55.24) *** | 175.66 | (23.98) *** | 181.05 | (22.44) *** |

| Legal status | 8.58 | (2.35) * | 2.73 | (.72) | 3.76 | (1.01) |

| Labor market experience | .90 | (4.97) *** | .84 | (4.73) *** | ||

| Education (years of schooling) | 1.91 | (3.96) *** | 1.50 | (3.13) ** | ||

| Age at arrival to the U.S. | −.68 | (−3.61) *** | −.55 | (−2.97) ** | ||

| Occupation: a | ||||||

| Technical, Sales, and Administrative | 5.31 | (1.44) | ||||

| Service | −7.87 | (−2.17) * | ||||

| Farming, Forestry, and Fishing | −10.24 | (−2.29) * | ||||

| Production, Craft, and Repairers | −1.87 | (−.40) | ||||

| Operatives and Laborers | −5.57 | (−1.46) | ||||

| Slopes (Monthly wage growth)† | ||||||

| Time (in months) | .20 | (1.27) | .01 | (.04) | .42 | (1.17) |

| Legal status | .13 | (.78) | .21 | (1.22) | .18 | (1.05) |

| Labor market experience | −.01 | (−1.18) | −.01 | (−1.08) | ||

| Education (years of schooling) | .03 | (1.38) | .04 | (1.69) + | ||

| Age at arrival to the U.S. | .01 | (.79) | .00 | (.52) | ||

| Occupation: a | ||||||

| Technical, Sales, and Administrative | −.60 | (−3.71) *** | ||||

| Service | −.47 | (−2.88) ** | ||||

| Farming, Forestry, and Fishing | −.24 | (−1.23) | ||||

| Production, Craft, and Repairers | −.29 | (−1.45) | ||||

| Operatives and Laborers | −.41 | (−2.50) * | ||||

| −2 log likelihood | −2145.7 | −2198.0 | −2323.2 | |||

Notes: N= 19,823 person-months

p < .001

p < .01

p < .05

p < .10 (two-tailed tests); coefficients and standard errors multiplied by 100; models are weighted and include control for SIPP survey panel (1996 or 2001)

“Professional and managerial occupations” are the reference category.

Human capital characteristics of Mexican immigrant women are added to the equation in the second column. For Mexican women, starting wages are higher for those with more labor market experience and schooling, and lower for immigrants arriving at later ages. Over our relatively short observation period, wage growth among this group of women is not differentiated by human capital characteristics. Most importantly, when these traits of workers are held constant, the legal status effect is reduced to a statistically insignificant 2.7%. This suggests that, for Mexican women, the wage premium associated with legal authorization is largely attributable to relatively benign labor market processes that reward better educated and more experienced workers.3

Lastly, the third column in Table 4 includes controls for Mexican immigrant women's occupation. Low-skill Mexican women working in service and farming, forestry, and fishing occupations report significantly lower wages than their counterparts in professional and managerial roles (the reference group). These occupational variables do little to further explain the (nonsignificant) legal status coefficient, and in fact appear to slightly suppress it. Additional analyses (available upon request) showed that occupation alone (in models not including human capital characteristics) does not explain the initial effect of legal status. Thus, as was true for the men, occupational sorting does not appear to play a noticeable role in wage differentiation between documented and undocumented Mexican immigrant women.

Legal Status and Returns to Human Capital

Men

Table 5 estimates separate growth curve models for males in each of the four low-skill ethnic/legal groups. This allows a full set of interactions between, on the one hand, immigrant and legal status, and on the other, wage predictors such as labor market experience and education.4 Significant differences in these effects between (1) documented and undocumented Mexican immigrants are noted in the table with a “d”; (2) Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans with an “m”; and (3) Mexican immigrants and white natives with a “w.” These sets of models thereby test whether the lower returns to human capital reported for Mexican immigrant men (Hall and Farkas 2008) are accounted for by the undocumented status of some of these workers.

Table 5.

Ethnic/Legal Group Specific Growth Curve Regression Coefficients Predicting Logged Wages, Men

| Documented Mexican Immigrants |

Undocumented Mexican Immigrants |

Mexican Americans (Natives) |

Non-Latino White Natives |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t | |

| Intercepts (Starting wage) | ||||||||

| Constant | 169.29 | (27.61) *** | 183.06 | (18.74) *** | 139.32 | (14.80) *** | 108.15 | (20.59) *** |

| Labor market experience | 1.13 | (8.33) ***m,w | .87 | (3.46) ***m,w | 1.54 | (10.43) *** | 1.56 | (36.68) *** |

| Education (years of schooling) | 3.53 | (8.03) ***m,w | 1.53 | (2.03) *d,m,w | 6.00 | (8.20) *** | 9.34 | (21.77) *** |

| Slopes (Monthly wage growth) | ||||||||

| Time (in months) | .97 | (4.39) *** | .14 | (.21) d,m,w | .86 | (2.69) ** | .81 | (4.67) *** |

| Labor market experience | −.01 | (−3.12) ** | .01 | (.65) d,m,w | −.02 | (−3.41) *** | −.01 | (−9.36) *** |

| Education (years of schooling) | −.02 | (−1.83) | .02 | (.40) | −.02 | (−.94) | −.02 | (−1.58) |

| −2 log likelihood | −2787.1 | 8 19.9 | −932.3 | 43 254.6 | ||||

| N of individuals | 1,149 | 375 | 828 | 9 ,917 | ||||

| N of person-months | 32,598 | 8,817 | 22,932 | 294,518 | ||||

Notes

p < .001

p < .01

p < .05

+ p < .10 (two-tailed tests); coefficients and standard errors multiplied by 100; models are weighted and include control for SIPP survey panel (1996 or 2001)

indicates that the coefficient is significantly different from that for documented Mexican immigrants

significantly different from Mexican Americans

significantly different from white natives (at p < .10).

The results clearly show that undocumented male workers receive lower starting wage returns to experience and schooling than the other groups, and that their average wage growth is lower than that of the other groups. For undocumented Mexican immigrants, the coefficient of labor market experience is .87. This means that for each additional year of labor market experience, starting wages for this group increase by 0.9 percent. There is a comparable effect for documented Mexican immigrants, about 1.1 percent. By contrast, Mexican American and non-Latino white natives gain significantly more from work experience, with each additional year associated with an increase in starting wages of about 1.5 percent.

Effects for years of schooling show even more striking inter-group differences. Thus, each additional year of schooling increases the starting wage rates of undocumented Mexican immigrants by 1.5 percent, whereas the effect for documented Mexican immigrants is 3.5 percent, that for Mexican American natives is 6.0 percent, and that for non-Latino white natives is 9.3 percent. This shows that a significant portion (but not all) of the lower returns to schooling received by Mexican immigrants (Hall and Farkas 2008) is due to the very low returns experienced by undocumented workers.

Finally, Table 5 shows average wage growth rates (the coefficient of time in the slope equation) of 0.1 percent per month for undocumented Mexican immigrants, 1.0 percent per month for documented Mexican immigrants, 0.9 percent per month for Mexican Americans, and 0.8 percent per month for non-Latino white natives. Clearly, undocumented immigrants have by far the lowest rate of wage growth.

Women

Table 6 shows corresponding growth curve model estimates for low-skill female workers, separately by ethnicity and legal status. As was true for men, documented Mexican immigrant women receive significantly higher wage returns to education than undocumented women. The second column shows that undocumented Mexican immigrant women receive a starting-wage increase of only 0.7 percent for each additional year of schooling. In contrast, documented Mexican immigrants receive a starting wage return to schooling more than twice as high (2.0 percent for each year of schooling). Importantly, the comparable coefficient for Mexican American women is even higher (5.1 percent), but still far below that of non-Latino white natives (9.3 percent). Thus, while all groups receive positive starting wage returns to schooling, those for undocumented women are by far the lowest. While this supports the idea that Mexican immigrants’ low returns to education are partially due to large shares of undocumented immigrants among the Mexican immigrant population, the fact that documented Mexican immigrants and native-born Mexican Americans receive much lower returns than white natives suggests that other underlying processes may be at work.

Table 6.

Ethnic/Legal Group Specific Growth Curve Regression Coefficients Predicting Logged Wages, Women

| Documented Mexican Immigrants |

Undocumented Mexican Immigrants |

Mexican Americans (Natives) |

Non-Latino White Natives |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t | |

| Intercepts (Starting wage) | ||||||||

| Constant | 172.53 | (22.80) *** | 173.94 | (9.76) *** | 138.41 | (13.35) *** | 87.66 | (13.58) *** |

| Labor market experience | .51 | (3.13) ***w | .72 | (1.73) + | .81 | (5.46) *** | 1.07 | (24.13) *** |

| Education (years of schooling) | 2.04 | (3.93) ***m,w | .68 | (.51) d,m,w | 5.08 | (6.34) *** | 9.28 | (17.41) *** |

| Slopes (Monthly wage growth) | ||||||||

| Time (in months) | .35 | (1.01) m,w | −.27 | (−.34) d,m,w | −.03 | (−.08) | .84 | (3.91) *** |

| Labor market experience | −.01 | (−.78) | −.01 | (−.70) | .00 | (−.14) | −.01 | (−4.44) *** |

| Education (years of schooling) | .02 | 0.88 w | .07 | (1.24) w | .04 | (1.58) | −.03 | (−1.81) + |

| −2 log likelihood | −1954.4 | −26 7.6 | −3741.7 | 24255.1 | ||||

| N of individuals | 732 | 171 | 742 | 9,323 | ||||

| N of person-months | 16,410 | 3,413 | 17,829 | 258,364 | ||||

Notes

p < .001

** p < .01

* p < .05

p < .10 (two-tailed tests) ; coefficients and standard errors multiplied by 100; models are weighted and include control for SIPP survey panel (1996 or 2001)

indicates that the coefficient is significantly different from that for documented Mexican immigrants

significantly different from Mexican Americans

significantly different from white natives (at p < .10).

The slope coefficients for women in Table 6 are generally nonsignificant. However, the large, positive, and significant growth coefficient for white natives indicates that the wages of foreign- and native-born Mexican immigrant women grow significantly slower than those for white natives. In addition, while the terms themselves are nonsignificant, the interaction terms indicate that undocumented Mexican immigrant women's wage growth is significantly lower than all the other groups.

Discussion

We provide new evidence on the wage benefits of having legal authorization to be in the U.S. for Mexican immigrants. In contrast to other research, this study uses recent, nationally-representative data to assess wage differentials between documented and undocumented Mexican immigrants, and the differential returns to human capital between these groups and native Mexican Americans and non-Latino whites. Using two panels (1996-1999 and 2001-2003) of longitudinal SIPP data, and employing a unique strategy of imputing immigrants’ legal status, we have shown that the wage premium of “being legal” for Mexican immigrants is approximately 17 percent for men and 9 percent for women. Although a considerable portion of the legal status wage premium is attributable to differences in labor market experience, educational attainment, and age at arrival to the U.S., male documented workers retain a significant wage advantage relative to their undocumented counterparts even when these factors are taken into account. Our analysis also demonstrated the very low returns undocumented Mexican immigrant workers receive from human capital. For both male and female undocumented Mexican workers, the wage returns to education are half of those realized by documented Mexican immigrants. Similarly, undocumented men receive lower returns to labor market experience than documented men. Also, in comparison to other low-skill workers (including documented Mexican immigrants) wage growth during our observation periods (1996-1999 and 2001-2003) was slowest for undocumented Mexican immigrants of both sexes.

The 17 percent gross wage differential we find between undocumented and documented Mexican immigrant men is within the range of previous post-IRCA estimates (Donato and Massey 1993; Kossoudji and Cobb-Clark 2002; Rivera-Batiz 1999). Less is known about the legal status wage differential for Mexican immigrant women, but our finding that documented women hold a wage premium of about 9 percent indicates that, like men, undocumented women face employment challenges in U.S. labor markets. Once our estimates are adjusted for worker characteristics (e.g., education, experience, age at arrival), legal Mexicans’ wage advantage drops to 7 percent for men, and a statistically insignificant 3 percent for women. This net wage differential is also in line with other studies (Kaushal 2006; Kossoudji and Cobb-Clark 2002; Rivera-Batiz 1999).

The gender differences in the effect of legal status and its mediating factors suggest not only that legal authorization is more consequential for the Mexican men's wage determination, but also that the underlying processes at work differ by sex. We initially suspected that occupational segregation may play an even stronger role for undocumented women than men, given that previous research has shown that the potent combination of gender, ethnicity, and nativity leads to a narrow range of occupations available to newly arrived, low-skill Latina immigrant women (Myers and Cranford 1998). We reasoned that moving into better-paid occupations would be more difficult for workers without legal authorization, potentially contributing to earnings differences by legal status. However, this explanation was not borne out by the data: occupation explained little of the difference in the effect of legal status among women, either before or after taking into account human capital factors.

Differences in migratory patterns for men and women may be a more promising explanation. In the migration stream from particular communities or families, the timing of men's migration tends to be earlier than that of women. Women often follow men as dependents or, if they themselves are labor migrants, migrate to join family or community members who have already established themselves in the U.S. (Donato, Wagner and Patterson 2008). Thus undocumented male workers are more likely to consider themselves temporary migrants whose intention is to return to families in Mexico, whereas women may see their migration as more permanent, regardless of legal status. Women are also more likely than men to be accompanied by families. Bonacich's (1972) split labor market theory posits that workers who view themselves as temporary migrants and who are unencumbered by dependents will be more willing to accept low pay and substandard living and working conditions. Thus for men, more so than women, lacking papers may correlate factors that make them willing to accept lower wages.

While it would be a mistake to completely dismiss the potential influence of legal status on earnings for Mexican immigrant women, our findings are consistent with previous literature in suggesting that other factors – particularly ethnicity, gender, and education – are more critical determinants of earnings for this group (Baker 1999). Mexican documented and undocumented women share ethnicity and gender and have similar levels of education. Given the extremely strong relationship between these factors and earnings, there may simply be little room for legal status to have an additional effect.

If, for men, the cost of being undocumented is not explained by workers’ human capital or by the types of jobs they hold, what explains the wage disparity? Labor market processes that cheapen the value of undocumented immigrants’ labor are one possible explanation. From the perspective of employers, a legal status wage gap is rational if governmental sanctions levied against them make hiring undocumented workers costly. These costs are, in turn, passed off as an effective tax on the wages of undocumented workers (Massey, Durand, and Malone 2002; Phillips and Massey 2000).

Employers, of course, are foremost in the business of profit-maximization, and will, assuming similarities in skill, hire workers with the lowest reservation wages. It is widely recognized that because of dual reference frames between origin and host countries, the reservation wages of immigrant workers are lower than those of natives, but they may also differ between documented and undocumented workers if the motives for work vary (see Bonaich 1972; Waldinger and Lichter 2003). Undocumented workers are, for example, more likely to intend their stays in the U.S. to be temporary or seasonal (Massey et al. 2002), and may thus be willing to accept lower wages to meet provisional or fixed goals. If this is true, our finding that undocumented workers receives lower returns to human capital and have wages that grow more slowly than other workers may indicate that undocumented workers substitute immediate earnings over investments in potential earnings. This line of reasoning parallels labor segmentation models, but the underlying mechanism – motives vs. split labor markets – differs.

Institutional and legal constraints also undoubtedly play important roles in explaining the legal status differentials in wages and returns to human capital. Not only are undocumented immigrants ineligible for many governmental assistance programs, for which legal immigrants are eligible, heightened animosity toward undocumented immigrants and harsh municipal policies related to where they can live and seek employment (Singer, Hardwick, and Brettell 2008) create an unstable and hostile social environment. As a result, undocumented immigrants often take the first job they are offered, continue to work in jobs even if the pay is low, or accept exploitative or illegal work conditions out of fear that they will be exposed.

We may actually be under-estimating the legal status wage premium if these processes are imposed on legal Mexican-origin workers (documented Mexicans and native Mexican Americans). Lowell, Teachman, and Jing (1995) demonstrated discrimination in hiring for all Latino-looking workers, not just the undocumented, as a result of IRCA-implemented employer sanctions. Bansak and Raphael (2001) and Orrenius and Zovodny (2009) show evidence of lower earnings for Latino workers as a function of increased enforcement. Donato et al. (2008) document similar processes for Mexican-origin women. Massey et al. (2002) go a step further and argue that the employment prospects and wages of legal Mexican immigrants are more greatly impacted by governmental sanctions and employer discrimination than those of undocumented Mexican immigrants: “Rather than protecting domestic workers, the criminalization of undocumented hiring ended up marginalizing [legal Mexican workers] by exacerbating income inequality, encouraging subcontracting, and generally promoting the informalization of hiring” (126). Thus, if the wages of documented Mexican immigrants are penalized as a result of illegal immigration, our legal status wage differentials are likely biased downwards.

If in fact these processes tied to legal status detrimentally affect the economic well-being of all Latino workers (regardless of legal status), they might explain why legal Mexican immigrants and (to a lesser extent) Mexican-American workers are less able to convert additional schooling into higher wages than non-Latino white natives. Nonetheless, the fact that only part of Mexican-origin workers’ low overall returns to human capital is explained by the abundance of undocumented migrants among their population is troubling, and is consistent with Telles and Ortiz's (2008) finding that Mexican Americans struggle to reach the kind of educational equality that other immigrants have achieved.

An important question for future research concerns what the future holds for undocumented workers. As xenophobia and public hostility toward undocumented Mexican immigrants has increased in recent years, and as political efforts are increasingly made to restrict both the flow and incorporation of these individuals, it is plausible that the wage penalties for not holding legal authorization may increase. Likewise, in times of economic crisis, immigrants are often scapegoated as the source of the problem. In supplemental models not shown but available on request, we tested for the possibility that the effect of legal status changed over time.5 We found no evidence that it did, but this may be attributable to our observation window (1996-2003) in which no major legislation was offered, public sentiment was less antagonistic, and economic conditions were reasonably robust, at least in comparison to the post-2005 period. Continuing to explore these issues clearly needs to be on the agenda for future research.

Acknowledgments

This research acknowledges support from the Population Research Institute of The Pennsylvania State University, which receives core funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Grant R24-HD041025). We are grateful to the editor, two anonymous reviewers, and Deb Graefe for their helpful comments.

Appendix

Appendix 1.

Imputation of Legal Status for Mexican Immigrants in SIPP

Appendix 2.

SIPP Survey Questions on Citizenship and Immigration Status

Footnotes

We reestimated our modes using lower bounds of $0.01 and $2.50 and upper bounds of $100.00 and $500.00. The results are consistent regardless of wage bound placement.

Descriptive statistics for Mexican immigrants in the 2001 panel with valid English ability information (N= 695 men and women) indicate that undocumented Mexican workers are less likely than documented Mexican immigrants to speak English well (36.3 vs. 51.1 percent, respectively), but the correlation (.12) between English ability and legal status is considerably smaller than those between English ability and education (.30) and age at arrival (−.26).

Additional analyses reveal that legal status is attenuated only when the full set of human capital characteristics are accounted for.

As the main goal of the group-specific models is to test differences in the returns to human capital, occupational controls are excluded from group-specific growth curve regressions.

These models were carried out by a series of interaction terms between legal status and (1) linear observation year; (2) individual year dummy terms; and (3) pre- and post-September, 2001. Intercept and slope coefficients for all of these terms were small and mostly nonsignificant.

Contributor Information

Matthew Hall, Department of Sociology and Population Research Institute Pennsylvania State University.

Emily Greenman, Department of Sociology and Population Research Institute Pennsylvania State University.

George Farkas, Department of Education and Department of Sociology University of California-Irvine.

References

- Baker Susan Gonzalez. Mexican-Origin Women in Southwestern Labor Markets. In: Browne Irene., editor. Latinas and African American Women at Work. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 1999. pp. 244–269. [Google Scholar]

- Bansak Cynthia, Raphael Steven. Immigration Reform and the Earnings of Latino Worker: Do Employer Sanctions Cause Discrimination? Industrial and Labor Relations Review. 2001;54:275–295. [Google Scholar]

- Bavier Richard. Welfare Reform Impacts in the SIPP. Monthly Labor Review. 2002;125:23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bean Frank D., Tienda Marta. The Hispanic Population of the United States. Russell Sage Foundation; New York, NY: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley Hoyt, Chin Aimee. Language Skills and Earnings: Evidence from Childhood Immigrants. The Review of Economics and Statistics. 2004;86:481–96. [Google Scholar]

- Borjas George J. The Economics of Immigration. Journal of Economic Literature. 1994;32:667–717. [Google Scholar]

- Borjas George J. Self-Selection and the Earnings of Immigrants. American Economic Review. 1987;77:531–553. [Google Scholar]

- Borjas George J. Assimilation, Changes in Cohort Quality, and the Earnings of Immigrants. Journal of Labor Economics. 1985;3:463–489. doi: 10.1086/298373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catanzarite Lisa. Brown Collar Jobs: Occupational Segregation and Earnings of Recent-Immigrant Latinos. Sociological Perspectives. 2000;43:45–75. [Google Scholar]

- Catanzarite Lisa, Aguilera Michael Bernabe. Working with Co-Ethnics: Earnings Penalties for Latino Immigrants at Latino Jobsites. Social Problems. 2002;49:101–127. [Google Scholar]

- Chiswick Barry. The Effect of Americanization on the Earnings of Foreign-Born Men. Journal of Political Economy. 1978;86:897–921. [Google Scholar]

- Cranford Cynthia J. Networks of Exploitation: Immigrant Labor and the Restructuring of the Los Angeles Janitorial Industry. Social Problems. 2005;52:379–397. [Google Scholar]

- Donato Katherine M., Wagner Brandon, Patterson Evelyn. The Cat and Mouse Game at the Mexico-U.S. Border: Gendered Patterns and Recent Shifts. The International Migration Review. 2008;42(2):330–359. [Google Scholar]

- Donato Katharine M., Wakabayashi Chizuko, Hakimzadeh Shirin, Armenta Amada. Shifts in the Employment Conditions of Mexican Migrant Men and Women: The Effect of U.S. Immigration Policy. Work and Occupations. 2008;35:462–495. [Google Scholar]

- Donato Katharine M., Massey Douglas S. Effect of the Immigration Reform and Control Act on the Wages of Mexican Migrants. Social Science Quarterly. 1993;74:523–541. [Google Scholar]

- Greene William H. Econometric Analysis. Prentice Hall; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hall Matthew, Farkas George. Does Human Capital Raise Earnings for Immigrants in the Low-Skill Labor Market? Demography. 2008;45:619–39. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoefer Michael, Rytina Nancy, Campbell Christopher. Estimates of the Unauthorized Immigrant Population Residing in the United States: January 2006. Office of Immigration Statistics, Policy Directorate, U.S. Department of Homeland Security; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Huffman Matt L., Philip N. Racial Wage Inequality: Job Segregation and Devaluation across U.S. Labor Markets. American Journal of Sociology. 2004;109:902–936. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman Robert L. Assessing Alternative Explanations for Race and Sex Employment Segregation. American Sociological Review. 2002;67:547–572. [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal Neeraj. Amnesty Programs and the Labor Market Outcomes of Undocumented Workers. Journal of Human Resources. 2006;41:631–647. [Google Scholar]

- Kmec Julie A. Minority Job Concentration and Wages. Social Problems. 2003;50:38–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kossoudji Sherrie A., Cobb-Clark Deborah A. Coming out of the Shadows: Learning about Legal Status and Wages from the Legalized Population. Journal of Labor Economics. 2002;20:598–628. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen Eric R., Gale Sarah M., Charpentier Paul E. Are Mexican Migrants to the U.S. Adversely Selected on Ability?; Paper presented at the 2008 meeting of the Association of Public Policy Analysis and Management; Los Angeles. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberson Stanley. A Piece of the Pie: Blacks and White Immigrants Since 1980. University of California; Berkeley, CA: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Lowell B. Lindsay, Teachman Jay D., Jing Zhongren. Unintended Consequences of Immigration Reform: Discrimination and Hispanic Employment. Demography. 1995;32:617–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas. Do Undocumented Migrants Earn Lower Wages than Legal Immigrants? International Migration Review. 1987;21:236–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S., Bartley Katherine. The Changing Legal Status Distribution of Immigrants: A Caution. International Migration Review. 2005;39:469–484. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S., Durand Jorge, Malone Nolan J. Beyond Smoke and Mirrors: Mexican Immigration in an Era of Economic Integration. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Orrenius Pia M., Zavodny Madeline. The Effects of Tougher Enforcement on the Job Prospects of Recent Latin American Immigrants. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 2009;28:239–257. [Google Scholar]

- Orrenius Pia M., Zavodny Madeline. Self-Selection among Undocumented Immigrants from Mexico. Journal of Development Economics. 2005;78:215–240. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips Julie A., Massey Douglas S. The New Labor Market: Immigrants and Wages after IRCA. Demography. 1999;36:233–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush Stephen W., Bryk Anthony S. Hierarchical Linear Models. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Batiz Francisco L. Undocumented Workers in the Labor Market: An Analysis of the Earnings of Legal and Illegal Mexican Immigrants in the United States. Journal of Population Economics. 1999;12:91–116. doi: 10.1007/s001480050092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeni Robert F. New Evidence on the Economic Progress of Foreign-Born Men in the 1970s and 1980s. Journal of Human Resources. 1997;32:683–740. [Google Scholar]

- Singer Audrey, Hardwick Susan W., Brettell Caroline B., editors. Twenty-First Century Gateways: Immigrant Incorporation in Suburban America. Brookings Institution; Washington, D.C.: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J. Edward. Undocumented Mexico-U.S. Migration and the Returns to Households in Rural Mexico. American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 1987;69:626–638. [Google Scholar]

- Tienda Marta, Lii Ding-Tzann. Minority concentration and Earnings Inequality: Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians Compared. American Journal of Sociology. 1987;93(1):141–165. [Google Scholar]

- Topel Robert H., Ward Michael P. Job Mobility and the Careers of Young Men. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 2649. 1988 [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau Annual Social and Economic Supplement. 2004 ( http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/foreign/ppl-176.html#la) (on earnings); http://www.census.gov/population/socdemo/foreign/p20-534/tab0111.pdf (on poverty)

- U.S. Department of Homeland Security . Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2006. U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics; Washington, D.C.: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Waldinger Roger. Black-Immigrant Competition Reassessed: New Evidence from Los Angles. Sociological Perspectives. 1997;40:365–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldinger Roger, Lichter Michael. How the Other Half Works: Immigration and the Social Organization of Labor. University of California; Berkeley, CA: 2003. [Google Scholar]