Abstract

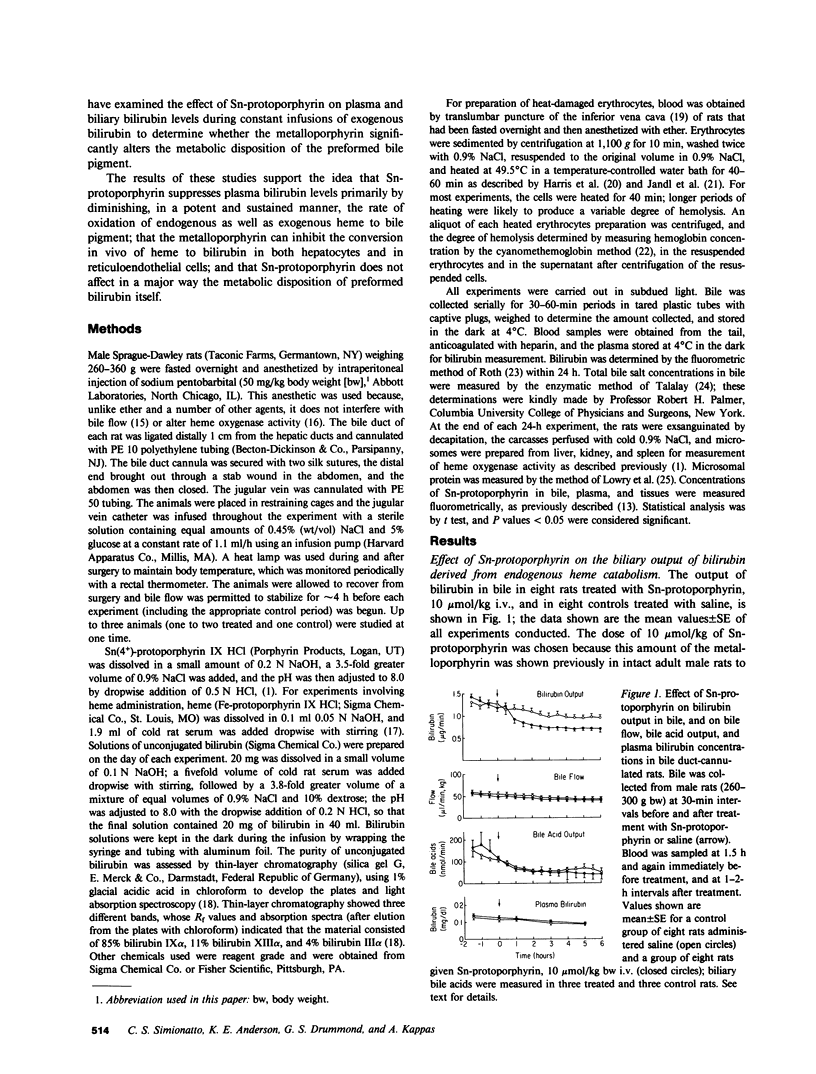

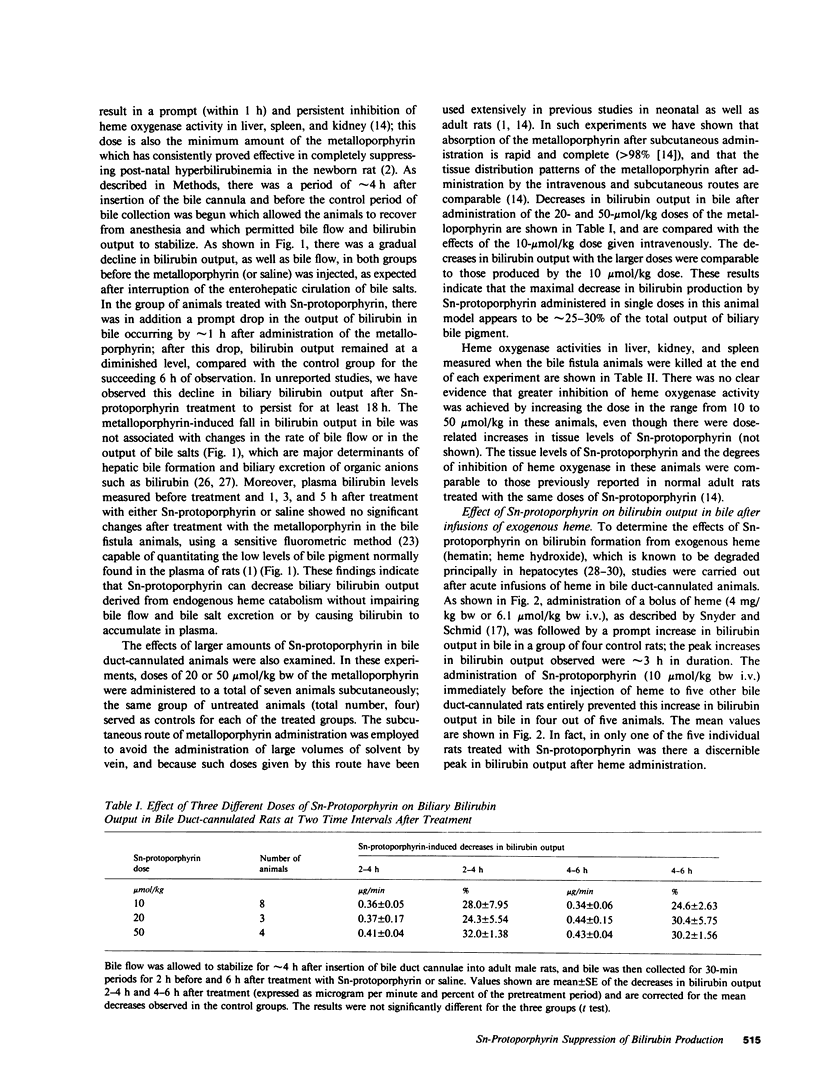

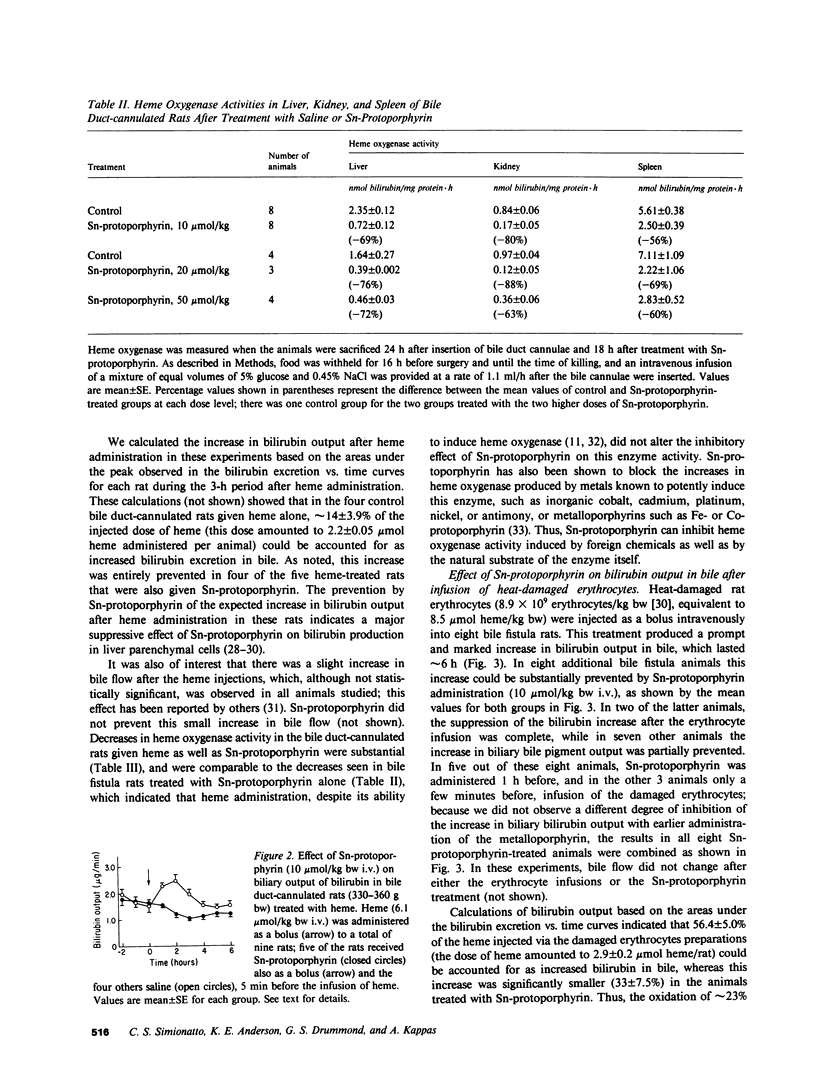

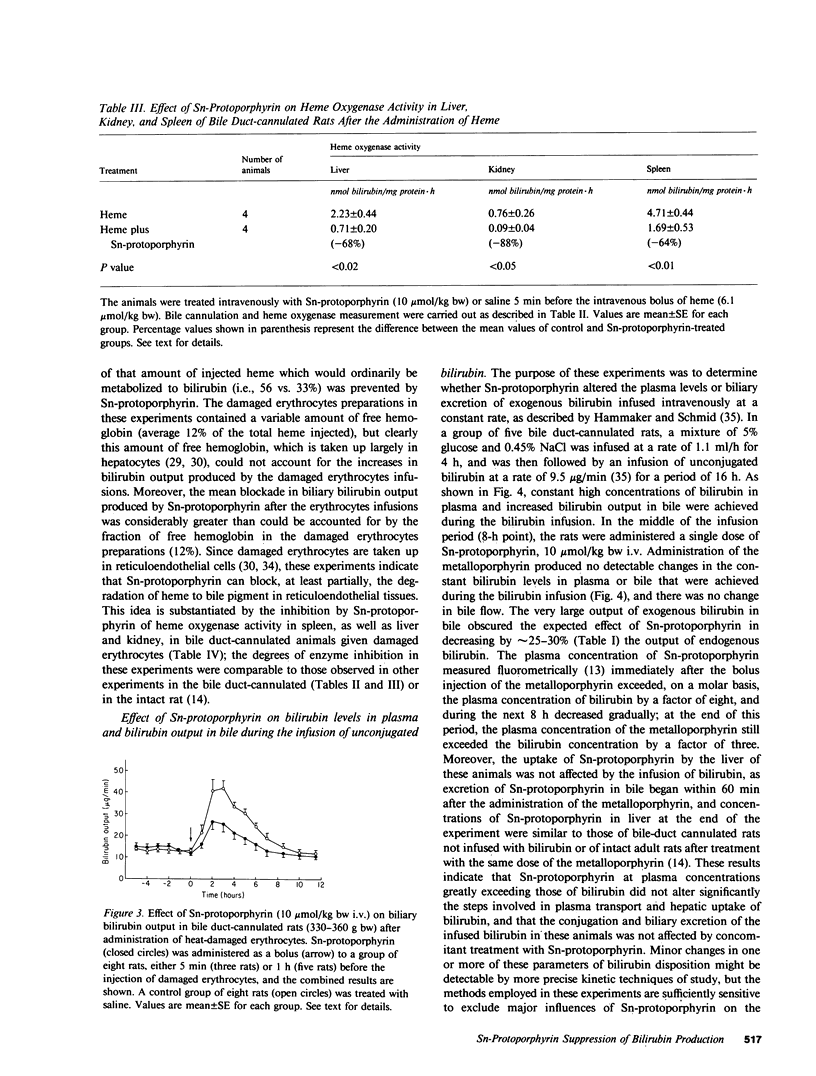

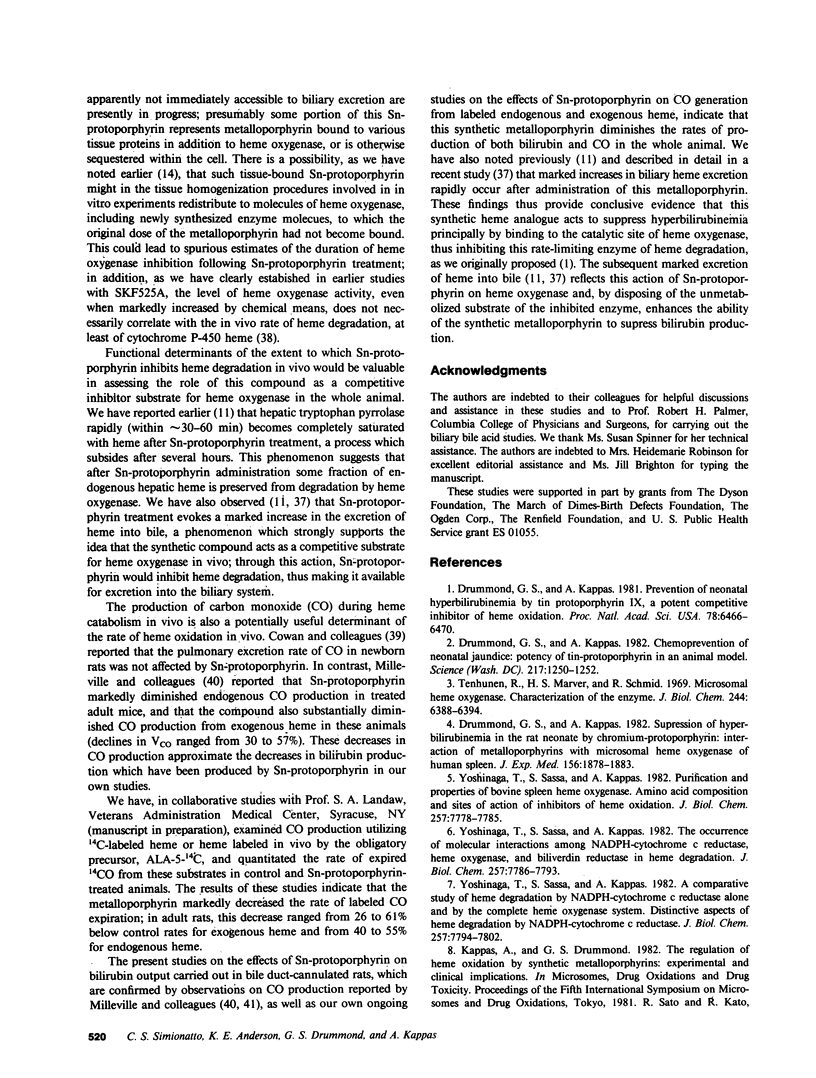

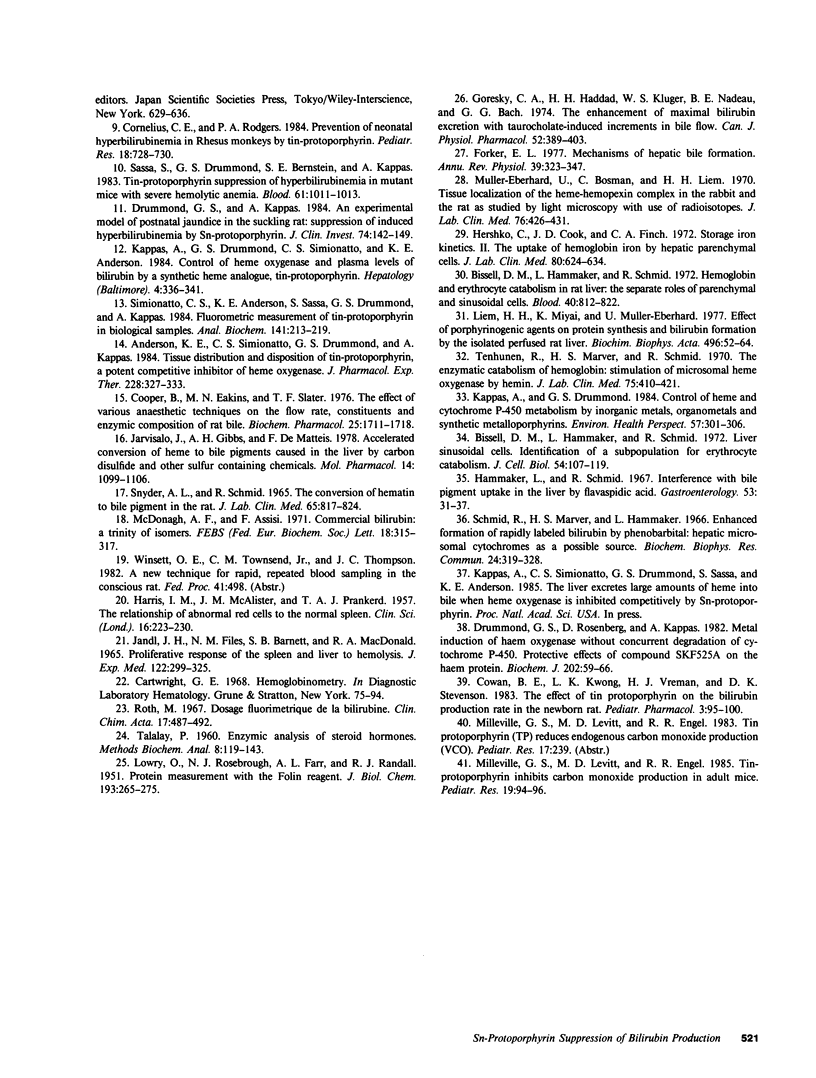

The synthetic heme analogue Sn-protoporphyrin is a potent competitive inhibitor of heme oxygenase, the rate-limiting enzyme in heme degradation to bile pigment, and can entirely suppress hyperbilirubinemia in neonatal animals and significantly reduce plasma bilirubin levels in a variety of circumstances in experimental animals and man. To further explore the mechanism by which this metalloporphyrin reduces bilirubin levels in vivo, we have examined its effects on bilirubin production in bile duct-cannulated rats, in which bilirubin derived from heme catabolism is known to be rapidly excreted in bile. The administration of Sn-protoporphyrin (10-50 mumol/kg body weight) was followed by prompt (within approximately 1 h) and sustained (up to at least 18 h) decreases in bilirubin output, to levels 25-30 percent below the levels of bilirubin output in control bile fistula animals. The metalloporphyrin had no effect on bile flow or the biliary output of bile acids. Infusions of heme, which is taken up primarily in hepatocytes, or of heat-damaged erythrocytes, which are taken up in reticuloendothelial cells, resulted in marked increases in bilirubin output in bile in control animals; these increases were completely prevented or substantially diminished by Sn-protoporphyrin administration. By contrast, the metalloporphyrin did not alter the high levels of bilirubin in plasma and bile that were achieved in separate experiments by the constant (16 h) infusion of unconjugated bilirubin to bile duct-cannulated rats. Thus, Sn-protoporphyrin exerts no major effects on the metabolic disposition of preformed bilirubin. Heme oxygenase activities were markedly decreased in microsomal preparations from liver, spleen, and kidneys in these experiments, to a degree comparable to the decreases we have observed in the intact rat. We also demonstrated that a substantial proportion (19-35%) of a dose of Sn-protoporphyrin is promptly excreted in bile and that the time course of biliary excretion of this compound more closely reflects plasma concentrations of the metalloporphyrin, which decline rapidly, rather than concentrations in liver, which are considerably more persistent. These results indicate that Sn-protoporphyrin substantially reduces the in vivo production of bilirubin from the degradation of endogenous as well as exogenous heme in the rat. Moreover, this inhibitory effect of the synthetic metalloporphyrin on bilirubin production occurs in both hepatocytes and reticuloendothelial cells, which are the major tissue sites for bilirubin formation. In other studies, we have established that heme oxygenase blockade by Sn-protoporphyrin leads to a marked and rapid excretion of heme into bile presumably because the synthetic metabolism to bile pigment and making it available for excretion via the biliary system in to the gut, These studies strongly suggest that Sn-protoporphyrin diminishes hyperbilirubinemia in animals and man by inhibiting the production of the bile pigment in vivo, and that its principal mode of action involves a potent and sustained competitive inhibition of heme oxygenase.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anderson K. E., Simionatto C. S., Drummond G. S., Kappas A. Tissue distribution and disposition of tin-protoporphyrin, a potent competitive inhibitor of heme oxygenase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1984 Feb;228(2):327–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissell D. M., Hammaker L., Schmid R. Hemoglobin and erythrocyte catabolism in rat liver: the separate roles of parenchymal and sinusoidal cells. Blood. 1972 Dec;40(6):812–822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissell D. M., Hammaker L., Schmid R. Liver sinusoidal cells. Identification of a subpopulation for erythrocyte catabolism. J Cell Biol. 1972 Jul;54(1):107–119. doi: 10.1083/jcb.54.1.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper B., Eakins M. N., Slater T. F. The effect of various anaesthetic techniques on the flow rate, constituents and enzymic composition of rat bile. Biochem Pharmacol. 1976 Aug 1;25(15):1711–1718. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(76)90403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius C. E., Rodgers P. A. Prevention of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia in rhesus monkeys by tin-protoporphyrin. Pediatr Res. 1984 Aug;18(8):728–730. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198408000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan B. E., Kwong L. K., Vreman H. J., Stevenson D. K. The effect of tin protoporphyrin on the bilirubin production rate in newborn rats. Pediatr Pharmacol (New York) 1983;3(2):95–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond G. S., Kappas A. An experimental model of postnatal jaundice in the suckling rat. Suppression of induced hyperbilirubinemia by Sn-protoporphyrin. J Clin Invest. 1984 Jul;74(1):142–149. doi: 10.1172/JCI111394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond G. S., Kappas A. Chemoprevention of neonatal jaundice: potency of tin-protoporphyrin in an animal model. Science. 1982 Sep 24;217(4566):1250–1252. doi: 10.1126/science.6896768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond G. S., Kappas A. Prevention of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia by tin protoporphyrin IX, a potent competitive inhibitor of heme oxidation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981 Oct;78(10):6466–6470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.10.6466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond G. S., Kappas A. Suppression of hyperbilirubinemia in the rat neonate by chromium-protoporphyrin. Interactions of metalloporphyrins with microsomal heme oxygenase of human spleen. J Exp Med. 1982 Dec 1;156(6):1878–1883. doi: 10.1084/jem.156.6.1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond G. S., Rosenberg D. W., Kappas A. Metal induction of haem oxygenase without concurrent degradation of cytochrome P-450. Protective effects of compound SKF 525A on the haem protein. Biochem J. 1982 Jan 15;202(1):59–66. doi: 10.1042/bj2020059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forker E. L. Mechanisms of hepatic bile formation. Annu Rev Physiol. 1977;39:323–347. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.39.030177.001543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goresky C. A., Haddad H. H., Kluger W. S., Nadeau B. E., Bach G. G. The enhancement of maximal bilirubin excretion with taurocholate-induced increments in bile flow. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1974 Jun;52(3):389–403. doi: 10.1139/y74-055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARRIS I. M., MCALISTER J. M., PRANKERD T. A. The relationship of abnormal red cells to the normal spleen. Clin Sci. 1957 May;16(2):223–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammaker L., Schmid R. Interference with bile pigment uptake in the liver by flavaspidic acid. Gastroenterology. 1967 Jul;53(1):31–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershko C., Cook J. D., Finch C. A. Storage iron kinetics. II. The uptake of hemoglobin iron by hepatic parenchymal cells. J Lab Clin Med. 1972 Nov;80(5):624–634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JANDL J. H., FILES N. M., BARNETT S. B., MACDONALD R. A. PROLIFERATIVE RESPONSE OF THE SPLEEN AND LIVER TO HEMOLYSIS. J Exp Med. 1965 Aug 1;122:299–326. doi: 10.1084/jem.122.2.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Järvisalo J., Gibbs A. H., de Matteis F. Accelerated conversion of heme to bile pigments caused in the liver by carbon disulfide and other sulfur-containing chemicals. Mol Pharmacol. 1978 Nov;14(6):1099–1106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappas A., Drummond G. S. Control of heme and cytochrome P-450 metabolism by inorganic metals, organometals and synthetic metalloporphyrins. Environ Health Perspect. 1984 Aug;57:301–306. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8457301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappas A., Drummond G. S., Simionatto C. S., Anderson K. E. Control of heme oxygenase and plasma levels of bilirubin by a synthetic heme analogue, tin-protoporphyrin. Hepatology. 1984 Mar-Apr;4(2):336–341. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840040227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWRY O. H., ROSEBROUGH N. J., FARR A. L., RANDALL R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951 Nov;193(1):265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liem H. H., Miyai K., Muller-Eberhard U. Effect of porphyrinogenic agents on protein synthesis and bilirubin formation by the isolated perfused rat liver. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1977 Jan 24;496(1):52–64. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(77)90114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonagh A. F., Assisi F. Commercial bilirubin: A trinity of isomers. FEBS Lett. 1971 Nov 1;18(2):315–317. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(71)80475-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milleville G. S., Levitt M. D., Engel R. R. Tin protoporphyrin inhibits carbon monoxide production in adult mice. Pediatr Res. 1985 Jan;19(1):94–96. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198501000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Eberhard U., Bosman C., Liem H. H. Tissue localization of the heme-hemopexin complex in the rabbit and the rat as studied by light microscopy with the use of radioisotopes. J Lab Clin Med. 1970 Sep;76(3):426–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth M. Dosage fluorimétrique de la bilirubine. Clin Chim Acta. 1967 Sep;17(3):487–492. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(67)90225-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SNYDER A. L., SCHMID R. THE CONVERSION OF HEMATIN TO BILE PIGMENT IN THE RAT. J Lab Clin Med. 1965 May;65:817–824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassa S., Drummond G. S., Bernstein S. E., Kappas A. Tin-protoporphyrin suppression of hyperbilirubinemia in mutant mice with severe hemolytic anemia. Blood. 1983 May;61(5):1011–1013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid R., Marver H. S., Hammaker L. Enhanced formation of rapidly labelled bilirubin by phenobarbital: hepatic microsomal cytochromes as a possible source. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1966 Aug 12;24(3):319–328. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(66)90158-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simionatto C. S., Anderson K. E., Sassa S., Drummond G. S., Kappas A. Fluorometric measurement of tin-protoporphyrin in biological samples. Anal Biochem. 1984 Aug 15;141(1):213–219. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90448-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TALALAY P. Enzymic analysis of steroid hormones. Methods Biochem Anal. 1960;8:119–143. doi: 10.1002/9780470110249.ch3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenhunen R., Marver H. S., Schmid R. Microsomal heme oxygenase. Characterization of the enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1969 Dec 10;244(23):6388–6394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenhunen R., Marver H. S., Schmid R. The enzymatic catabolism of hemoglobin: stimulation of microsomal heme oxygenase by hemin. J Lab Clin Med. 1970 Mar;75(3):410–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshinaga T., Sassa S., Kappas A. A comparative study of heme degradation by NADPH-cytochrome c reductase alone and by the complete heme oxygenase system. Distinctive aspects of heme degradation by NADPH-cytochrome c reductase. J Biol Chem. 1982 Jul 10;257(13):7794–7802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshinaga T., Sassa S., Kappas A. Purification and properties of bovine spleen heme oxygenase. Amino acid composition and sites of action of inhibitors of heme oxidation. J Biol Chem. 1982 Jul 10;257(13):7778–7785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshinaga T., Sassa S., Kappas A. The occurrence of molecular interactions among NADPH-cytochrome c reductase, heme oxygenase, and biliverdin reductase in heme degradation. J Biol Chem. 1982 Jul 10;257(13):7786–7793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]