Abstract

Nail-patella syndrome (NPS) is a pleiotropic autosomal-dominant disorder due to mutations in the gene LMX1B. It has traditionally been characterized by a tetrad of dermatologic and musculoskeletal abnormalities. However, one of the most serious manifestations of NPS is kidney disease, which may be present in up to 40% of affected individuals. Although diagnosis can be made at birth, it is often missed, presumably due to the rarity of the condition.

A 35-year-old female presented to our clinic with history of small joint pain of 6 months duration. In addition she complained of pedal edema off and on for the last 12 years. Prior to her current presentation she had been managed by a local doctor symptomatically. On evaluation, a nephrotic syndrome was obvious, but no secondary cause could be found. However, her physical examination was characteristic of NPS and keeping in view the autosomal dominant nature of the disorder all her three siblings were screened who too showed classical features of NPS. This rare syndrome as a cause of nephrotic range proteinuria is discussed in this report. The report underlines the importance of a good physical examination in a given clinical setting.

Keywords: nail-patella syndrome, arthropathy, proteinuria, nephropathy

Zusammenfassung

Nagel-Patella-Syndrom (NPS) ist eine pleiotrope, autosomal-dominante Erkrankung auf der Basis einer Mutation im Gen LMX1B. Das NPS wurde traditionell als eine Tetrade von dermatologischen und skelettmuskulären Veränderungen charakterisiert. Eine der schwerwiegendsten Manifestationen von NPS ist jedoch eine Nierenerkrankung, die bei 40% der betroffenen Personen auftritt. Obgleich die Diagnose bereits bei der Geburt erfolgen kann, wird diese wegen der Seltenheit der Störung oft nicht gestellt.

Eine 35-jährige Frau stellte sich in unserer Klinik wegen Schmerzen in den kleinen Gelenken, die seit 6 Monaten bestanden, vor. Außerdem klagte sie über Beinödeme, die seit 12 Jahren immer wieder auftraten. Bislang war sie von einem Hausarzt symptomatisch behandelt worden. Für das festgestellte nephrotische Syndrom konnte keine Ursache gefunden werden. Die körperliche Untersuchung ergab allerdings charakteristische Zeichen einer NPS. Aufgrund des autosomal-dominanten Erbganges wurden ihre drei Geschwister untersucht, die ebenfalls klassische Symptome von NPS aufwiesen. Dieses seltene Syndrom als Ursache einer nephrotischen Proteinurie wird in diesem Bericht diskutiert. Der Bericht unterstreicht die Bedeutung einer guten körperlichen Untersuchung im gegebenen klinischen Umfeld.

Introduction

Nail-patella syndrome (NPS) is a pleiotropic autosomal-dominant disorder but significant variations in its clinical expression are known [1]. The syndrome was first described as a hereditary disease by Little in 1897 [2] and later the gene was traced to be adenylate kinase gene [3] on the long arm of chromosome 9. The classic tetrad of manifestations of NPS reflect dysplasia of structures derived from the dorsal mesenchyme. These include absent or hypoplastic finger and toe nails; absent or hypoplastic patellae; elbow dysplasia, often involving posterior sub-luxation of the radial head; and iliac horns [1]. Although not part of the defining tetrad of clinical findings, kidney disease occurs in greater frequency in individuals with NPS than in the general population, an association first explicitly noted by Hawkins and Smith [4] in 1950. Because of the rarity of the disorder, most publications concerning kidney involvement in NPS have either been case reports or small series. Hematuria and proteinuria have often been noted, as have numerous anecdotal reports of progression to kidney failure, even in childhood [5]. Various other renal abnormalities include urologic malformations, nephrolithiasis [6] but due to rarity of the syndrome detailed data continues to lack.

Case description

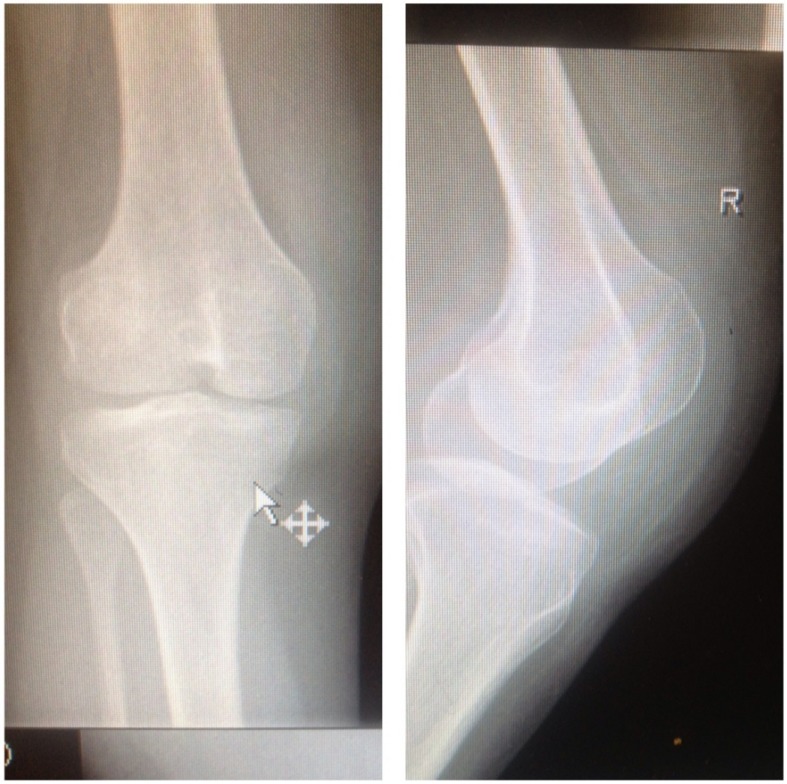

A 35-year-old female presented with joint pains of 6 months duration to the rheumatology clinic of King Abdul Aziz specialist hospital Taif in the western region of Saudi Arabia. She described pain as being intermittent, score of 3/10 mostly in the small joints of hands. There was no history of morning stiffness, fever, rash or limitation of activities of her daily life. There was no history of numbness, tingling or weakness in any of her limbs. She also complained of pedal edema off and on for the past 12 years. The patient is a non-diabetic, normotensive lady and denied any history of easy fatigability or loss of appetite. She has normal menstrual cycles and she had delivered three full term babies. However each of her pregnancy was complicated by increase in her pedal edema, but she never had eclampsia. Records showed that the range of proteinuria during her pregnancy remained 1.4 g to 2.9 g in 24 hr urinary collection. There was no history of gestational hypertension. She had been managed in a local hospital and had been offered kidney biopsy which she never consented to. The clinical examination of the patient showed an obese lady (BMI was 31 kg/m2) with stable vitals. There was no pallor or lymphadenopathy. She had a gross bilateral pedal edema which was pitting in nature. The musculoskeletal examination showed dystrophic nails (Figure 1 (Fig. 1)) and a bilateral absence of patella with normal range of movement in all her joints. There was no malar rash or any joint deformities and none of her joints was swollen. The examination didn’t reveal any evidence of exostoses of the hips, hypoplasia of iris and her both scapulae were normal. Her hair and teeth were also normal. Apart from these findings observed on clinical examination her systemic examination was unremarkable. On evaluation she had hemoglobin of 13 g/dl, white blood count (WBC) and platelets were within normal range. Her liver function and kidney function tests were normal. A 24 hr urine collection showed albumin of 4 g/L. Her anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) and double stranded DNA levels were normal. She had negative rheumatoid factor. She was euthyroid and her lipid profile was also normal. Serum and urine electrophoresis showed no abnormality. The ultrasound abdomen showed normal size of both kidneys with maintained corticomedullary differentiation. With regard to her nail changes a dermatological consultation was sought and possibilities of Lichen planus, psoriasis and eczema were ruled out in this patient. Keeping in view her long duration of pedal edema due to nephrotic range proteinuria, the characteristic dystrophic nail changes, an X-ray of knees demonstrated the absence of bilateral patella (Figure 2 (Fig. 2)). Consequently her siblings were screened for NPS as well. All her children showed classical features of NPS as shown in Figure 3 (Fig. 3). Hence a diagnosis of NPS was made on clinical grounds and kidney biopsy was cancelled. She was started on thermotherapy for her joint pains and Tab. Enalpril 5 mg once daily. She was also advised weight reduction and regular exercise. She has been doing well with an improvement in her albuminuria and is regularly attending our clinic for the last 2 years now.

Figure 1. Dystrophic thumb nails in the index case.

Figure 2. Absent patella.

Figure 3. Absent patella and dystrophic nails in children (3A: Limited extension of the elbow; 3B: Prominent tibial and lateral condyles of both tibia due to aplastic patella; 3C: Dystrophic nail of the son).

Discussion

The index case had history of nephrotic range proteinuria with maintained renal functions over a period of 12 years. Her work up didn’t reveal any secondary cause of nephrotic syndrome. The clinical examination clinched the diagnosis and keeping in view the autosomal dominant nature of the syndrome the genetic penetrance was confirmed in her siblings as well. The syndrome is rare but it is very important to be aware of this clinical entity as its diagnosis can save unnecessary investigations including kidney biopsy based purely on clinical examination. Kidney biopsy is, however, carried out in a given case of NPS only if there is a suspicion of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or diabetic nephropathy in addition. Generally kidney biopsy is discouraged in this syndrome as there seems no clear relationship between renal pathology of NPS and it s clinical behavior. The natural history of NPS shows that progressive kidney disease affects a small minority of patients with NPS: estimates range from 3% [1] to 15% [7]. Patients with NPS may present with hematuria and an incidence of approximately 10–20% has been described [1]. Patients invariably continue to be normotensive but follow up hypertension and other risk factors may help to retard kidney dysfunction in the long run. Significant questions remain concerning the prognosis of individuals detected with abnormal albuminuria and a normal glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Nephrotic range proteinuria has often been associated with loss of kidney function over variable periods of time. There are no specific treatments for kidney involvement in NPS. The lack of longitudinal studies of kidney involvement in NPS makes it difficult, if not impossible, to determine precisely which clinical features characterize progression to end-stage kidney failure. It has been suggested that screening for nephropathy should be done annually, starting at birth. Although spot urine protein/creatinine or albumin/creatinine ratios are more sensitive than routine urinary dipstick analysis, there is, as yet, no evidence that intervention in the microalbuminuric phase will alter outcome. For example, it is, as yet, unknown if such patients always manifest nephrotic range proteinuria prior to progression to kidney failure. A strongly renoprotective effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibition on disease progression has been demonstrated in a variety of non-diabetic, proteinuric, glomerular diseases [8]. There are reports of treatment with cyclosporin [9], [10]. A trial of cyclosporin may be a reasonable option for individuals who either don’t respond to ACE inhibitor treatment or else develop unacceptable side effects like angioedema or hypotension. There are numerous anecdotes of patients with NPS who have undergone successful transplantation after developing terminal kidney failure [9], [11]. Other routine screening is ophthalmology examination for detection of glaucoma.

It may be concluded that the present case brings to the fore the importance of a good clinical examination in a given clinical setting in order to clinch the diagnosis of this rare syndrome and avoid unnecessary investigation. Family screening is warranted to evaluate and manage siblings of the case in order to retard renal disease progression.

Notes

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

References

- 1.Sweeney E, Fryer A, Mountford R, Green A, McIntosh I. Nail patella syndrome: a review of the phenotype aided by developmental biology. J Med Genet. 2003 Mar;40(3):153–162. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.3.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Little EM. Congenital absence or delayed development of the patella. Lancet. 1897 Sep 25;150(3865):781–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)64875-4. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)64875-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schleutermann DA, Bias WB, Murdoch JL, McKusick VA. Linkage of the loci for the nail-patella syndrome and adenylate kinase. Am J Hum Genet. 1969 Nov;21(6):606–630. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawkins CF, Smith DE. Renal dysplasia in a family with multiple hereditary abnormalities including iliac horns. Lancet. 1950 Apr 29;1(6609):803–808. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(50)90636-2. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(50)90636-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyrier A, Rizzo R, Gubler MC. The nail-patella syndrome. A review. J Nephrol. 1990;2:133–40. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mittal R, Saxena S, Hotchandani RK, Agarwal SK, Tiwari SC, Dash SC. Bilateral renal stones associated with nail-patella syndrome. Nephron. 1994;68(4):509. doi: 10.1159/000188328. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000188328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bongers EM, Huysmans FT, Levtchenko E, de Rooy JW, Blickman JG, Admiraal RJ, Huygen PL, Cruysberg JR, Toolens PA, Prins JB, Krabbe PF, Borm GF, Schoots J, van Bokhoven H, van Remortele AM, Hoefsloot LH, van Kampen A, Knoers NV. Genotype-phenotype studies in nail-patella syndrome show that LMX1B mutation location is involved in the risk of developing nephropathy. Eur J Hum Genet. 2005 Aug;13(8):935–946. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201446. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.GISEN Group (Gruppo Italiano di Studi Epidemiologici in Nefrologia) Randomised placebo-controlled trial of effect of ramipril on decline in glomerular filtration rate and risk of terminal renal failure in proteinuric, non-diabetic nephropathy. Lancet. 1997 Jun 28;349(9069):1857–1863. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)11445-8. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(96)11445-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Callís L, Vila A, Carrera M, Nieto J. Long-term effects of cyclosporine A in Alport’s syndrome. Kidney Int. 1999 Mar;55(3):1051–1056. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.0550031051.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.0550031051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charbit M, Gubler MC, Dechaux M, Gagnadoux MF, Grünfeld JP, Niaudet P. Cyclosporin therapy in patients with Alport syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007 Jan;22(1):57–63. doi: 10.1007/s00467-006-0227-y. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00467-006-0227-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McIntosh I, Dreyer SD, Clough MV, Dunston JA, Eyaid W, Roig CM, Montgomery T, Ala-Mello S, Kaitila I, Winterpacht A, Zabel B, Frydman M, Cole WG, Francomano CA, Lee B. Mutation analysis of LMX1B gene in nail-patella syndrome patients. Am J Hum Genet. 1998 Dec;63(6):1651–1658. doi: 10.1086/302165. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/302165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]