Abstract

Why this matters to me

I have been involved in developing different forms of community-oriented integrated care since 1989 when I set up the Liverpool Primary Care Facilitation Project. I never cease to be amazed at how effective and enjoyable it is when primary care practitioners and managers can work together across organisational boundaries to improve healthcare for local populations. I also never cease to be surprised at how hard it seems to be for many to believe that such an approach could be even contemplated, let alone systematically taught, applied and evaluated.

In West London, I have seen the valuable effect of the Integrated Care Pilot at providing one of the key ingredients of community-oriented integrated care – geographic clustering of general practices (termed Health Networks) that provide a regular space where people of different disciplines can come together to learn from and with each other, and co-create things that improve the health of local people. I believe that the April 2014 changes to the England GP contract provide an opportunity for these Health Networks to make a quantum leap in achieving community-oriented integrated care and with it a renaissance of the NHS.

Keywords: Community Oriented Integrated Care, NHS, Whole Systems

The direction of travel – community-oriented integrated care

Avoiding hospital admission is the aim of the changes to the England GP contract from April 2014.1 In total, 341 of the 739 points will be removed from Quality Outcomes Framework (QOF), of which 238 will be transferred to core funding and 103 to enhanced services (ESs).

Core general practitioner (GP) funding will require all patients over 75 years of age to have a named GP. A new Unplanned Admissions ES will complement this by requiring case management of 2% of patients over 18 years of age who are most at-risk of hospital admission – £160 million has been set aside to pay for this. Box 1 lists the main changes for practices. A few other ESs will continue: Dementia, Learning Disabilities, Alcohol and Patient participation, and these can be woven into an integrated strategy for care of vulnerable patients.

Box 1. Changes to GP contract.

The England GP contract and Unplanned Admissions extended services are described at bma.org.uk/working-for-change/negotiating-for-the-profession/bma-general-practitioners-committee/general-practice-contract/qof-changes-2014. They list three fundamental changes in the role of primary care. They require practices to:

1. Have systems for multiple-way fast communication and access

From April 2014:

Patients will need to be able to book appointments and order repeat prescriptions online

Practices will need a bypass number for other professionals (e.g. A&E, ambulance, Care & Nursing Homes) to quickly communicate with primary care practitioners

Practices will provide same-day telephone advice for patients on the Case Management Register

Practices will need to act on triggers that a care plan may need to be reviewed (e.g. contact patients who are discharged from hospital)

And by 31 March 2015:

Patients must have online access to their summary care records (medications, allergies, adverse reactions and any additional information that they have explicitly consented to)

Practices must have an automated system to upload summary information to the Summary Care Record (SCR), and additional information (when consented), to support patient care

Practices will provide out-of-hours Services (OOH) information about patients' special needs

Practices will use the GP2GP facility for the transfer of patient records between practices

2. Evaluate quality

Friends and Family Test Question: ‘How likely are you to recommend our practice to friends and family if they needed similar care or treatment?’

Practices will be required to display the CQC inspection outcome in their waiting room(s) and on the practice website

GP practices will comply with systems that the OOH provider puts in place for rapid and effective transmission of OOH patient data, especially about patients with special needs

Practices will monitor the quality of OOH services with regard to the national quality standards and any reported patient feedback

Practices will review the clinical details of all OOH consultations on the same working day they are received by a clinician

Practices will review monthly unplanned admissions & readmissions, and A&E attendances of their patients from care and nursing homes, looking for avoidable causes

Practices will share relevant information and any whole system commissioning action points with their CCG

3. Case manage elderly and vulnerable patients

Risk stratification tools will identify the top 2% ‘at risk’ patients aged over 18 years, and from this, practices will create a case management register. Practices will also put others on the case management register when it seems appropriate (including children)

All patients on the case management register and all patients aged 75 years and older will have a ‘named GP’ who is accountable for ensuring that all appropriate services are provided. New elderly patients need to be informed who is their named GP within 21 days of registration and existing elderly patients by 30 June 2014

Patients on the case management register will also need a ‘Care Coordinator’ who could be different from the named GP. This person is responsible for ensuring that the care plan is followed and is up to date

Especially for those on the case management register, the named GP will work with health and social care professionals to deliver a multidisciplinary care package that meets the needs of the patient. The existing ICP meetings In West London could be developed to support this

Practices will undertake monthly reviews of the case management register to consider what action can be taken to prevent unplanned admissions of patients on the register

The combination of case management and named GPs signals a clear direction of travel – primary care, within Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), is expected to orchestrate the care of vulnerable patients, especially those with long term conditions (LTCs). To do this, practices will have to build relationships with other community-based providers to develop multidisciplinary care teams around each patient at the local, community level. This is community-oriented integrated care (COIC) – care that is integrated at the community level. COIC has the potential to be holistic and cost-efficient because it can deal with the full range of diseases that dominate people's lives; it contrasts with integration at the specialist level that deals with (usually medically-defined) diseases, one at a time. COIC is too much for any one practice to orchestrate on its own, and practices will need to collaborate with other practices in the same geographic areas. An area with a population of 50 000 is about right – small enough to feel you belong and large enough to have a political effect. This is the size of the ‘Health Networks’ already established in West London through the Integrated Care Pilot (ICP).2

Practices will need to do less reactive care and more proactive (planned) care for patients with LTCs – especially diabetes, which is expected to affect 10% of the population of West London within a few years. To do this, practices will need a greater level of organisation than before, including systems of review, teams for different aspects of care, and ongoing health promotion. At the same time they will need to align their activities with those of partner agencies, so everyone can engage in annual cycles of inter-organisational improvement. Furthermore, primary care is expected to evaluate all of this, and will need skills to generate and interpret data about these ‘whole systems of care’.

New ways of working and new skills will be needed (actually they are not so new, as Box 1 shows, but they are unfamiliar). These include Senge's concept of a learning organisation,3 in which systems thinking helps individuals to link their actions with ‘bigger pictures’, practices to work within care pathways, and workbased learning to develop multidisciplinary ‘shared leadership’.

This paper describes how all this can be achieved through an integrated plan that achieves multiple objectives at the same time. West London Health Networks could chart a course to achieve this over time; different Health Networks could pilot different aspects and feed back learning to all.

Participation in geographicallybased Health Networks

Practices can try to achieve the new England GP contract requirement to orchestrate the care of so many people with LTCs on their own. But this requires maintaining creative relationships with large numbers of people outside of the practice – a lot of work. Furthermore, maintaining an infrastructure of communication and facilitation to evaluate out-of-hours services and feed back information to CCGs in a way that provides useful learning could be onerous.

A more successful strategy would be for practices to work within geographic clusters of general practices (termed Health Networks in West London) to share the load. This approach will also help to achieve other important needs, such as seven day working, teaching the future workforce and developing a primary care research agenda. Already, the work of our close allies in public health and social care is impeded by the lack of shared geographic areas to collaborate and coordinate activities – clustering could improve this.

There are many ‘communities’ whose work could be enhanced by working with clusters of general practices, and who would bring much more than they would take. Once the basic approach is mastered, Health Networks could achieve ‘added extra’ by working with those concerned with:

Research: research recruitment, translational and applied research, whole systems research

Evaluated service improvements: Leadership skills, multiple methods participatory action research, experience-based co-design

Training: Undergraduate and postgraduate doctors, nurses, managers and social workers; school children

Health promotion: HealthWatch, Public health, local community action

Child and family health: Schools, voluntary sector, faith communities

The media and performing arts, business and community regeneration

If Health Networks were to develop the capacity to lead multiple-way collaborations for whole population health they would re-enliven the principles of the NHS in a modern context, developing models of community-oriented integrated care of international importance. This would have the effect of re-defining the concept of ‘public service ethos’, not as the source of (public or private) funding, but as purposeful engagement in collaboration for whole population health.

If they did this, on the proverbial ‘Monday morning’, general practice will look the same as it did before. There will still be patients to be seen, and information to be processed. Everyone will ‘get on their trains’ as usual. But the work done to align activities will mean that the various ‘trains’ will connect to produce a network of inter-connecting routes – integrated care.

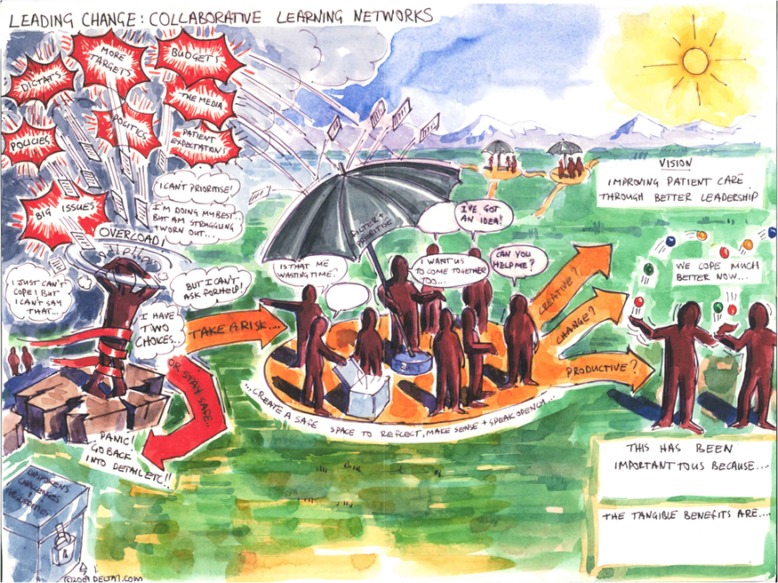

Figure 1 gives a visual image of what can happen when people from different parts of a system stand back and work together (reproduced with kind permission of Julian Burton from Delta7). The first stage is obvious – standing back with a core team helps to make sense of the rain of demands and coordinate a team effort for effective action. This image also applies to practices within a Health Network, and even to each person individually – reflective practice and checklists are forms of standing back to make sense of multiple demands. Later stages are less immediately obvious – these multiple ‘learning spaces’ (Health Networks) also need to connect, and the annual schedule needs to include feedback, stakeholder workshops and cascading conferences to help integrate their work.

Figure 1.

Box 2. What is community-oriented integrated care?

Community-oriented integrated care is care that is integrated at community level

Governments throughout the world started to put in place policies for Community-Oriented Integrated Care from 1978 when delegates at the World Health Organisation conference at Alma Ata agreed that integration at the primary care level is an essential ingredient of high quality, cost-effective healthcare systems (then they called it ‘comprehensive primary health care’).4 Integration at specialist levels is less effective because specialists deal with one disease at a time, and this has the effect of fragmenting things at more local levels. Conversely, it is the role of community-based generalists to make sense of the full range of diseases (not merely medical diseases) of patients. Also, generalists are better placed to harness a range of local inputs to improve the health of a patient in a holistic way, and to work with local agencies to make locally-relevant health improvements.

Community-oriented integrated care values fairness (social justice). This believes that society will be more ‘healthy, wealthy and wise’ when the health of everyone is considered, without excluding people by virtue of having a certain characteristic (e.g. wealth, class, gender, ethnicity).

But with the concept of social justice comes rights and responsibilities5 – everyone must do their bit to improve their own health and that of their communities. In turn, professionals need to help people to help themselves, by understanding their conditions, understanding how the healthcare system works, and agreeing goals for improvement – this is what a care plan should do.

The emphasis on participation, community development and social justice focuses attention on the processes that integrate individual activity across organisational and disciplinary boundaries – the ‘bigger picture’ of health and care. This contrasts with the dominant NHS approach that focuses on the structures that support individual practitioners to act in isolation.

Community-oriented integrated care uses organisational learning principles that help practitioners and managers from different organisations and disciplines to learn from and with each other. Senge described ‘systems thinking’ as the key discipline of a learning organisation that integrates four other disciplines (team learning, personal mastery, mental models and building shared vision).3

Community-oriented integrated care reframes the concept of public service ethos as collaborating with others for whole population health (different from the common definition of being employed by a ‘public’ or a ‘private’ organisation). This emphasis on collaboration challenges a combative definition of ‘competition’ – it suggests that people should compete to lead collaborative activities.

To make the most of the new England GP contract and to use this move towards community-oriented integrated care, general practices need to:

Plan the ‘nuts and bolts’ of care planning

Align external activities, through ‘Seasons of Care’

Integrate within-practice activities, through multi-disciplinary teams

Share responsibility for care plans through patient participation

Practices also need to work within Health Networks and CCGs to:

-

5.

Nurture relationships with partner agencies, through annual cycles of inter-organisational improvement

-

6.

Coordinate education provision

The rest of this paper explores practical ways to do these things. One approach would for different Health Networks to pilot different aspects and feed back their learning to all.

1. The ‘nuts and bolts’ of care planning

Care planning requires three quite different activities that can be led by different teams – 1) Everything to do with the case management register, 2) Everything to do with making a care plan, 3) Everything to do with reviewing a care plan.

1.1. Case management register

There are two ways to identify the patient who should be on the case management register:

Risk profiling: With CCG support, use a risk profiling tool (e.g. BIRT2) to identify the top 2% of your patients (over age 18 years) who should be on your case management register

Clinical judgement: When a practitioner sees someone who they think would benefit from a Care Plan; this should include vulnerable children

Care planning may not require more time overall. It does, however, mean using time differently since care plans require a proactive approach that is different from the reactive approach that is more common in general practice. So a practice might as well consider a similar approach for less complex LTCs (e.g. asthma). They could set up two registers.

Practices will benefit if different Care Plan templates are simultaneously auto-populated through everyday activities. Key activities and ‘triggers’ need to be coded:

Care plans that have had an annual update or ongoing review: This will help to identify those patients who have not, and need to be pursued

Monthly review of unscheduled events (admissions, A&E, use of advice line and other consultations): This will help to identify those who need a care plan review

CCGs could provide IT support to help practices to achieve this. Clinical Support Units could provide ongoing monitoring of the impact of this local action on hospital episodes.

1.2. Making a care plan

Completed care plans are only useful if they are ‘live’ documents. The main person to use them is the patient, but they may also be useful to someone who does not have the full records (e.g. out-of-hours practitioners). A full set of information needs to be on the GP computer system, but more useful for patients and professionals alike is a succinct summary that helps them to know what to do. This should include:

A narrative that can be held by the patient, family and out-of-hours practitioners (e.g. for Special Patient Notes and Message in a Bottle). It should include diagnoses, medications, allergies, place of care, advance directives, who to contact

Patient data and targets e.g. routine annual screening, home monitoring, patient goals updated and selected measures as proxies for ongoing progress

Support agencies to call when the patient needs help

1.3. Reviewing a care plan

Patients need options for reviewing their care plan throughout the year. This includes:

Alongside other events such as the flu campaign and health promotion campaigns

Clinics and groups: Long-term condition clinics, self-help groups, drop-in centres

Distant advice via telephone, email, electronic device

2. ‘Seasons of Care’ to align external activities

More than merely updating care plans is needed – all partner agencies within a Health Network need to align their activities. They must do this to address the issues within the plans, and also to engage in ongoing inter-organisational improvements. Without capacity to innovate in synchrony, the system will become mechanical and inflexible. When such capacity exists a range of exciting new opportunities for innovation are possible, including novel collaborations to get ‘added extra’ from various resources (e.g. community, academic, schools and others).

Thankfully, the annual calendar has seasons that everyone recognises, providing natural times when everyone is doing similar things. These seasons can frame a schedule of collaborative activities.

These seasons include:

January–March: everyone is preparing their end of financial year reports, including gathering data and completing last-minute targets

April–July: as the weather gets warmer and the budget for the year is known, everyone have more head-space to think about ‘bigger pictures’ and longer-term planning

October–December: as the weather gets colder, people get into project management mode, ready for ‘winter pressures’ and the ‘flu campaign

July and December: as the main annual holidays loom, everyone tries to clear their desks to enjoy being away without worrying about work

These seasons could shape annual cycles of collaborative activity:

April–July

Practices could do almost their entire data gathering for care planning in the April-July period. Patients' handheld records (backed up by SMS messages or email) will advise them when to get their annual tests done and, in advance, they can be sent the required forms. Every week practices would hold LTC Annual Care Plan Update Clinics (as distinct from LTC Review Clinics to be held throughout the year) at which nurses (‘Care Coordinators’) and named (accountable) GPs would work side-by-side to negotiate care plans and patient goals (e.g. home monitoring, exercise, or weight loss). At that clinic patients could be given an autumn date for their ‘flu jab when they will have their care plan goals reviewed, and also advised of the on-going clinics and facilities to support them between these times

Health promotion campaigns could be continuous in these months, including public health and HealthWatch (voluntary sector) leadership of borough-wide campaigns, including the media and multiple community-based groups. Within practices, leaflets and posters could advertise these campaigns. Practices could hold their own campaigns with talks, videos, self-help groups and workshops to help patients help themselves

Shared leadership teams made up of practitioners and managers from local organisations will have been preparing for many months plans to lead coordinated improvements throughout their Health Network. They could host a local stakeholder event in these months for partner agencies to agree their targets for change (later that autumn)

By the time of the August break, the bulk of the data gathering and care plans for patients on the case management register (and possibly others) could have been done, and patients will hold their own record of their status and their plans. Patients will know what they have to do and how they will get help in the other months of the year (e.g. LTC Review Clinics) to review and move these plans forward

September–November

Actions required for Health Network improvement projects could be piloted between September and November. A Clinical Support Unit could gather data about the use of NHS services of patients from different Health Networks to demonstrate the overall effect of these actions on hospital admissions. Academic partners could support generation and interpretation of data relevant to these improvement projects

The practice team(s) charged with overseeing the care plan system can seek out those who missed the April–July annual review of care plans to make sure they are completed before the winter break. They will also plan the ‘flu campaign’ with care plan review

In November, a CCG-wide stakeholder conference could review progress of all its Health Networks, providing a mechanism to pool learning from all parts of the borough to inform policy and priorities for the following year. This would be a good point for the shared leadership teams that have led the previous year's work to stand down, forming new teams for the coming year, and thereby providing a mechanism for ongoing development of leadership skills

By the time of the December break, all routine data and actions should have been completed, leaving only ongoing monitoring and last minute ‘fixing’ for the January–March period. The new leadership teams will start to design improvement projects that will be presented for approval at July local (Health Network) stakeholder conferences

January–March

This period (as usual) will involve data gathering and tidying up, in preparation for the end of financial year accounts. Activity in the other seasons should have prevented the need for routine data generation and review of care plans.

January–March is a good time for whole system training events; learning from the past year has been distilled, and trajectory for the next has become clear, so training can have strategic focus. At such events large numbers of people from different disciplines meet in a half-day workshop to: a) Update their knowledge about the topic; b) Critique the emerging plans for improvement; and c) Develop relationships across disciplinary boundaries, thereby providing a mechanism for many disciplines to contribute to the design of local improvement plans

Health Network shared leadership teams could use informants at whole system training events to hone their ideas about improvement projects. These informants, coupled with feedback from Health Networks and surveys, could also identify educational needs for a range of disciplines for the year ahead. Partner agencies could prepare educational materials, including videos, podcasts and web-based materials (to reach those who do not attend the meetings), and launch these in different months of the year, creating an annual cycle of coordinated learning

Throughout the year

Weekly practice-based LTC Review Clinics and opportunistic actions by clinicians and receptionists when patients attend for other reasons

Monthly Health Network review of data about progress with Care Plans and Innovations

Quarterly CCG- or sector-wide workshops for shared leadership teams to cross-pollinate ideas and learn increasingly sophisticated ways to lead the development of communities of practice and whole systems of care (combined vertical and horizontal integration of care)

3. Multidisciplinary teams – for integrated working within the practice

The new England GP contract requires clinical and administration staff to work together to devise and operate the system for patients on the case management register. For example, care plans require a ‘named (accountable) GP’ and ‘care co-coordinator’, as well as a ‘usual clinician’ and other key care plan team members (e.g. carers); after hospital discharge one of these people needs to contact the patient. Administrators need to help everyone to distinguish these roles that at first sight might confuse people.

Patients on the case management register need to be able to access same-day telephone advice, and the practice also needs an ex-directory/bypass number for other clinicians to call to discuss their care (e.g. A&E clinicians, ambulance staff, care & nursing homes). Also, the practice needs to regularly (monthly) review information about episodes of care in other places (e.g. admissions and unscheduled visits), and code them in ways that help later planning and lessons for the practice and for the CCG.

Clinicians need to help administrators to understand what is realistic for them to do, and administrators need to help clinicians to do it. The following administrator/practitioner teams will be needed to manage the complexities involved:

3.1. Internal communication team

This team devises and oversees plans to keep everyone (especially part-timers) informed about changes within and without the practice, and also a way to consult everyone about new proposals. They need to have a mechanism (e.g. a person) to register things that could be improved in all aspects of internal communication – rotas, portfolios, visitors & meetings, and improvements in the IT System, including referral forms and tests.

3.2. External communication team

This team has a similar role to the ‘internal communication team’ (they could even be the same people) but this team pays attention to links outside of the practice. This includes an updated register of key contacts from partner agencies, as well as analysing and coding information from other places.

3.3. Monitoring (e.g. QOF & Health Network reports) team

Practices have a large number of reports to complete and data to review throughout the year – QOF and network targets, for example, as well as internal improvement projects and shared projects with partner agencies. This team draws up an annual schedule to show when data and reports are needed, and prompts the relevant people to deliver these in a timely manner.

3.4. Patient participation and quality improvement team

This team coordinates quality improvements, ensuring patient participation and everything to do with ‘Seasons of Care’) above.

3.5. IT support

Practice staff need to be able to deal with IT problems – they cannot rely solely on external agencies. Often simple things are needed, such as helping a locum to login or reboot the computer. On other occasions more complex things are needed such as templates to amend to support a practice improvement project. Leaders of this team need to work closely with the other teams to provide practical support for all strategies.

4. Patient participation to share responsibilities for care plans

Patients with LTCs need to contribute to writing their care plans because this is the way that they will understand and agree their responsibilities. By contributing to quality improvements more broadly (e.g. practice or Health Network improvements) they provide valuable insights that are often invisible to those delivering care. Furthermore, patient participation in collaborative service improvements motivates them to become powerful allies for the practice in many other ways. The central role of patient participation in quality improvements explains why mechanisms to facilitate their engagement should be woven into the overall plan. Three different strategies are needed: 1) Patientheld care plans, 2) Patient access to information, and 3) Patient participation in quality improvements. For each, practices need to emphasise the mutual advantage of participation, and the ground rules for engagement (e.g. providing data to help the practice achieve its targets).

4.1. Patient-held care plans with their annual targets and milestones

Section 3 above describes ‘Seasons of Care’ as a way to align activities. Adopting this approach is time-efficient because patients will themselves make sure that they provide the data needed for their annual reviews between April and July – long before the final deadline for QOF targets. This gives practices plenty of time to chase up those who don't engage. Also it allows synchronous ‘health promotion weeks’ to reach a large number of relevant people.

4.2. Patient access to records, test results and electronic repeat prescriptions

By 31 March 2015, patients must have online access to their summary care records (SCRs; medications, allergies, adverse reactions and any additional information they have explicitly consented to). Practices must have an automated system to upload summary information to SCRs and provide out-of-hours services information about patients' special needs. This is the same information required for the care plan summary. It makes sense for all practices to pilot these things straight away, so that they can be easily achieved in 2015.

4.4. Co-design of service improvements

Experience-based co-design6 describes how services can be effectively designed with the participation of all who experience them (patients, administrators and clinicians). A sequence of multidisciplinary workshops (set within ‘Seasons of Care’) can support the design and evaluation of services by revealing needs, hopes and constraints of different players; accommodating these permits a better plan to emerge than when services are designed merely by one group.

5. Shared projects to nurture relationships with partner agencies

‘Seasons of Care’, described above, help to align activities outside the practice as well as within. Adopting this approach is effective because different organisations can contribute at strategically useful times to develop a ‘community of support’ – a set of ‘connected communities’.7 For example, in the April–July season, when making care plans the practices are likely to refer many patients with diabetes to the ‘tier two’ Intermediate Care Diabetes service. Practitioners from that service could attend practice or Health Network health promotion events for everyone to feel part of a whole system of care.

For CCGs and Health Networks to enable the most appropriate shared projects to be developed year after year, they need an annual cycle of inter-organisational collaborative improvement as described in ‘Seasons of Care’ above. This will have the effect of providing a sustainable mechanism for continuous inter-organisational quality improvement. Practices and Health Networks can prepare for this by piloting models that help people of different backgrounds to creatively interact.

5.1. A database of partner agencies

Healthcare professionals often emphasis medical care, and limit the concept of partner agencies to the statutory Primary, Intermediate and Hospital Care, and Social Services and Public Health. But from a patient's perspective these are often not as important for their day to day well-being as third sector organisations – Age UK, Diabetes UK, social clubs and faith communities, for example. A Health Network directory of resources is a good first step to making good use of these resources – HealthWatch groups (www.healthwatch.co.uk) often create such directories and these could be pointed towards the Health Network areas.

5.2. Shared projects arising from sequential stakeholder conferences

As well as knowing that an agency exists, a trusted relationship helps to work well with them. If you have a trusted relationship you can pick up the telephone and get something done. If you don't, it is much harder.

Creating something good with others is a reliable way to build trusted relationships. Health Networks and CCGs can pilot annual cycles of inter-organisational improvements that stimulate shared projects that build trusted relationships. Each year interorganisational leadership teams can be supported to lead small, coordinated improvements as described in ‘Seasons of Care’ above, and from these build a complex network of inter-organisational trust.

5.3. Family conferences

Healthcare professionals often use case conferences to explore what different partner agencies can do for a patient. But chief among partners are families of patients, and they often only convene in a crisis. It would make sense for practices to offer patients under case management a family conference before a crisis happens, to help everyone to understand what they can do to help. This could even become a routine expectation, promoting planning for long-term needs, long before it becomes called end of life care.

5.4. Coordinated Educational Provision

Practices need protocols for running LTC clinics. Time can be saved by developing these across a CCG or Health Network. Such collaboration can also identify learning needs, and these can be communicated to the CCG and to Local Education and Training Boards to support a systematic approach to educational provision. For example, partner agencies (e.g. a musculoskeletal service) could provide annual training courses and self-help resources.

As well as personal skills, practitioners need in-the-moment decision-support. It is unrealistic to expect then to remember everything about all LTCs and there will be times when their immediate work colleagues are unable to help. So they need quick access to specialist advice, including email advice lines and mobile phone access to consultants – bringing specialist knowledge right into the generalist consulting room.

As well as knowledge of diseases, effective case management requires practitioners to have high level consultation skills that surface and appreciate social and emotional factors. To do this, practitioners and managers need to learn techniques from motivational interviewing,8 cognitive behavioural therapy9 and narrative-based consulting.10

As well as personal care, practitioners and managers need to be skilled at engaging teams, networks and communities in collaborative improvements. To do this, practitioners and managers need to learn techniques from participatory action research,11 large group interventions12,13 and appreciative inquiry.14

A paradigm shift?

This paper argues that the 2014 changes in the England GP contract provide the opportunity for a quantum leap in quality of care and a rediscovery of the old NHS principles of whole population health. This entails a shift from focus on the structured ‘silos’ of a National Health ‘Service’, towards dynamic interaction for collaboration within a National Health ‘System’, to nurture an integration of effort at local (community) level – hence community-oriented integrated care.

The approach advocated in this paper comes from a systems analysis – how different things can connect to produce effects that are greater than the sum of its parts. Two images of connection are implied – a machine image and a learning organisation image.15 These images are examples of Checkland's ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ systems.16 Both are helpful to reveal how ‘top down’ and ‘bottom up’ processes can be integrated to facilitate on-going inter-organisational improvements.

A hard system has unchanging mechanical parts that fit together in predictable ‘linear’ ways – Health Networks, LTC clinics, stakeholder conferences and reports are examples of the ‘fixed parts’ of a machine. Without these fixed structures people will not even be able to get into each other's company to start a process of collaboration.

But hard structures alone do not cause innovation – this requires dynamic processes of reflection, shared learning and shared action within and between these structures. This is what Checkland calls a ‘soft system’, Stacey calls a ‘complex adaptive system’17 and Pratt calls a ‘whole system’18 – multiple interactions and coadaptations that give rise to awe, motivation and a sense of unity.

These modern theories of systems, complexity and learning all agree with the Darwinian notion that the natural state of life is complex co-adaptation. The policy implications of this image are that NHS practitioners and managers (and indeed school children) need to be trained in the science and art of enabling creative interaction between people of different insights and roles, and CCGs need to support co-design of locally-relevant solutions. These are quite different from the expert and bureaucratic conclusions that derive from the static ‘laboratory’ image that has underpinned so much NHS policy in the past (as Easmon describes in his LJPC paper on workforce). Hopefully, the new England GP contract will stimulate a deep exploration of these paradigm issues, potentially to the benefit of all public service.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Those who worked with me and contributed to my thinking about community-oriented integrated care over the years.

RELATED LJPC PAPERS:

Steeden A. The Integrated Care Pilot in North West London. London Journal of Primary Care 2012;5:8–11. www.radcliffehealth.com/LJPC/article/integrated-care-pilot-north-west-london

Morris D. Introducing Volume 6 of London Journal of Primary Care: community-oriented integrated care. London Journal of Primary Care 2014;6:1–2. www.radcliffehealth.com/LJPC/article/introducing-volume-6-london-journal-primary-care-community-oriented-integrated-care

GOVERNANCE

This paper is a personal view that uses already published papers and does not require formal governance

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None

REFERENCES

- 1.Nagpaul C. England GP contract 2014–2015. bma.org.uk/working-for-change/negotiating-for-the-profession/bma-general-practitioners-committee/general-practice-contract/qof-changes-2014 (accessed 14/03/2014).

- 2.Steeden A. The Integrated Care Pilot in North West London. London Journal of Primary Care 2012;5:8–11 www.radcliffehealth.com/LJPC/article/integrated-care-pilot-north-west-london (accessed 14/03/2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Senge P. The Fifth Discipline. Century Hutchinson: London, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macdonald JJ. Primary Health Care: Medicine in its place. Earthscan Publications: London, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giddens A. The Third Way. Polity Press: Malden, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.The King's Fund. Experience-Base Co-Design Toolkit. www.kingsfund.org.uk/projects/ebcd (accessed 14/03/2014).

- 7.Morris D. Introducing Volume 6 of London Journal of Primary Care: community-oriented integrated care. London Journal of Primary Care 2014;6:1–2 www.radcliffehealth.com/LJPC/article/introducing-volume-6-london-journal-primary-care-community-oriented-integrated-care [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Motivational Interviewing. In Wikipedia. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Motivational_interviewing (accessed 14/03/2014).

- 9.David LS, Freeman GK. Improving consultation skills using cognitive-behavioural therapy: a new ‘cognitive-behavioural model’ for general practice. Education for Primary Care 2006;17(5):443–452. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Launer J. Narrative-based Primary Care: A practical guide. Radcliffe Medical Press: Oxford, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whyte WF. Participatory Action Research. SAGE: New York, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bunker BB, Alban B. Large Group Interventions – engaging the whole system for rapid change. Jossey-Bass: California, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Passmore W, Bunker BB, Jacobs R. et al. Large group interventions. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 1992;28(4)480–498. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooperrider DL, Sorenson PF, Jnr Yaeger TF, Whitney D. Appreciative Inquiry: An Emerging Direction for Organizational Development. Stipes: Champaign, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morgan G. Images of Organization. SAGE: Thousand Oaks, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Checkland P. Systems Thinking, Systems Practice. Wiley: Bath, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stacey Ralph. Complexity and Creativity in Organisations. Berrett-Koehler: San Francisco, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pratt J, Gordon P, Plamping D. Working Whole Systems : putting theory into practice in organisations. Radcliffe Publishing: Oxford, 2005. [Google Scholar]