Abstract

Prolonged stress (≥ six months) may cause a condition which has been named exhaustion disorder (ED) with ICD-10 code F43.8. ED is characterised by exhaustion, cognitive problems, poor sleep and reduced tolerance to further stress. ED can cause long term disability and depressive symptoms may develop. The aim was to construct and evaluate a self-rating scale, the Karolinska Exhaustion Disorder Scale (KEDS), for the assessment of ED symptoms. A second aim was to examine the relationship between self-rated symptoms of ED, depression, and anxiety using KEDS and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD). Items were selected based on their correspondence to criteria for ED as formulated by the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare (NBHW), with seven response alternatives in a Likert-format. Self-ratings performed by 317 clinically assessed participants were used to analyse the scale’s psychometric properties. KEDS consists of nine items with a scale range of 0–54. Receiver operating characteristics analysis demonstrated that a cut-off score of 19 was accompanied by high sensitivity and specificity (each above 95%) in the discrimination between healthy subjects and patients with ED. Reliability was satisfactory and confirmatory factor analysis revealed that ED, depression and anxiety are best regarded as different phenomena. KEDS may be a useful tool in the assessment of symptoms of Exhaustion Disorder in clinical as well as research settings. There is evidence that the symptom clusters of ED, anxiety and depression, respectively, reflect three different underlying dimensions.

Keywords: Stress, cognitive problems, exhaustion disorder, KEDS, screening, burnout

Introduction

Psychiatric illness has become a major cause for long-term sick leave (Järvisalo et al., 2005). In Sweden, the leading category of psychiatric conditions that may call for sick leave is Reaction to severe stress, and adjustment disorders (F43 in the ICD-10 classification), with depressive disorders as the second most common category (Swedish Social Insurance Agency, 2010). Among the reactions to stress is the condition caused by chronic, unrelenting, but not life threatening stress. This condition is characterized by prolonged fatigue, sleep disorder, cognitive problems and an increased sensitivity to further stress, which may lead to anxiety reactions.

In spite of the typical clinical picture, chronic stress disorder is not yet recognized in any of the major psychiatric classification systems. Because the relevant stress is often occupational, it has sometimes been referred to as “burnout” or “chronic/clinical burnout syndrome,” (Ekstedt, Söderström & Åkerstedt, 2009; Grossi, Perski, Ekstedt, Johansson, Lindström & Holm, 2005; Sandström, Rhodin, Lundberg, Olsson & Nyberg, 2005). Professional burnout as described Freudenberger (1974), Maslach (1982) and Schaufeli and Enzmann (1998) is, however, a much broader psychological concept characterized by emotional exhaustion, cynicism and reduced professional accomplishment. Thus, the ICD-10 recognizes burnout among Problems related to life management difficulty (Z73.0), but not as a medical condition. The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare (NBHW) have provided tentative diagnostic criteria (Table1) for chronic stress, and suggest that the term exhaustion disorder (ED) and the ICD code F43.8 should be used. Using this diagnostic concept, Saboonchi, Perski and Grossi (2012) found that most of the variance in ED could not be explained by burnout, as assessed with the Shirom Melamed Burnout Questionnaire (Melamed, Kuschnir & Shirom, 1992).

Table 1.

Criteria for Exhaustion Disorder according to the National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden

| A. Physical and mental symptoms of exhaustion during at least two weeks. The symptoms have developed in response to one or more identifiable stressors present for at least six months. |

| B. The clinical picture is dominated by markedly reduced mental energy, as manifested by reduced initiative, lack of endurance, or increased time needed for recovery after mental effort. |

| C. At least four of the following symptoms have been present, nearly every day, during the same 2-week period: |

| 1/ Concentration difficulties or impaired memory |

| 2/ Markedly reduced capacity to tolerate demands or to work under time pressure |

| 3/ Emotional instability or irritability |

| 4/ Sleep disturbance |

| 5/ Marked fatigability or physical weakness |

| 6/ Physical symptoms such as aches and pains, palpitations, gastrointestinal problems, vertigo or increased sensitivity to sound |

| D. The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in occupational, social or other important respects. |

| E. The symptoms are not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a drug of abuse, a medication) or a physical illness/injury (e.g., hypothyroidism, diabetes, infectious disease). |

ED-symptoms overlap with those of many other psychiatric disorders, particularly depression, and there is an on-going discussion whether clinical burnout, ED and other prolonged fatigue states should be included among the affective disorders, and best diagnosed as cases of depression or anxiety, rather than classified as diseases in their own right (Cho, Skowera, Cleare & Wessely, 2006; Glass & McKnight, 1996). Although many ED patients fulfill diagnostic criteria for depression at some stage of their illness, the low mood is often temporary while the core symptoms of ED (exhaustion, cognitive problems, sleep disturbance) remain. Perski and Grossi (2004) suggested that a depressive state might be a consequence or a complication of stress-related emotional exhaustion, rather than the core problem.

The decision of the NBHW to recommend that ED be used as a diagnostic classification was based almost entirely on clinical experience, which suggested that the prolonged course of the condition and the poor effect of standard antidepressant treatment (Bryngelson, Mittendorfer-Rutz, Jensen, Lundberg, Åsberg & Nygren, 2012) differentiated ED from major depressive disorder. Recent research suggests that the genetic background (Gizatullin, Zaboli, Jonsson, Åsberg & Leopardi, 2008; Zaboli et al., 2008), the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis reactivity (Rydmark, Wahlberg, Ghatan et al., 2006; Wahlberg, Ghatan, Modell et al., 2009), the increased blood concentrations of cellular growth factors such as VEGF and EGF (Åsberg, Nygren, Leopardi, Rylander, Peterson & Wilczek, 2009) and possibly also the neurobiological concomitants (Jovanovic, Perski, Berglund & Savic, 2011; Blix, Perski Berglund & Savic, 2013) may differentiate the two conditions.

In order to test possible differences in course, as well as treatment outcome of ED and depression, respectively, sensitive rating scales are needed. Chronic stress symptoms are presumably not rare in the general population, and a rating scale might aid in the differentiation between normal tiredness and exhaustion disorder. Measures of burnout such as the Maslach Burnout Inventory (Maslach & Jackson, 1986) are strongly focused on work and are not easily applicable to patients who are on long-term sick leave or out of work. The same objection applies to work focused fatigue scales such as the Occupational Fatigue Exhaustion/Recovery Scale (OFER; Winwood, Winefield, Dawson & Lushington, 2005) and the Swedish Occupational Fatigue Inventory (SOFI; Åhsberg, Gamberale & Kjellberg, 1997). A few rating scales for exhaustion disorder or clinical burnout have been created (Glise, Hadzibajramovic, Jonsdottir & Ahlborg, 2009; Saboonchi et al., 2012), but validated cut-off scores between cases and normal conditions have not yet been presented.

The aim of the present study was to construct and evaluate the psychometric properties of a self-rating scale for assessment of ED symptoms, with focus on the scale’s ability to differentiate between individuals with and without ED. Secondarily; we aimed to investigate the relationship between self-assessed symptoms of ED and depression, and between ED and anxiety, to evaluate the construct validity of the new ED scale.

Methods

Construction of the scale

The construct to be measured was defined by the criteria for ED, formulated by the NBHW in 2003 (Table1). Items in KEDS were chosen on the basis of their correspondence to ED criteria A–C. Six items were selected from the Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale (CPRS; Åsberg, Montgomery, Perris, Schalling & Sedvall, 1978), namely, CPRS items 4, 5, 15, 16, 17 and 19. Another four items were formulated on the basis of symptoms often reported by ED patients. The 10 items in the initial version of KEDS were: (1) ability to concentrate, (2) memory, (3) physical stamina, (4) mental stamina, (5) recovery, (6) sleep, (7) sensory impressions, (8) emotional engagement, (9) experience of demands, and (10) irritation and anger. The CPRS items were rephrased where appropriate, to fit with the vocabulary and definitions found in autobiographical reports or descriptions made by patients suffering from ED. One example is the “stamina” items, which were originally a single item. As patients have pointed out that “stamina” could refer to mental as well as to physical phenomena, these distinctions were made clear by formulating two separate items. Each KEDS item had seven unipolar response alternatives ranging from 0-6, with higher values reflecting more severe symptoms. Definitions were formulated at score 0, 2, 4 and 6 but not at 1, 3 and 5 (see Appendix).

A panel of psychiatrists, experienced psychotherapists and ED-patients (altogether 15 individuals), agreed that items and terminology were relevant except for item 8 (emotional engagement). This item was excluded as it reflects one of the two main DSM criteria of depression but is not particularly typical of ED. Hence, the final version of the scale consists of nine items (see Appendix).

KEDS was originally formulated in Swedish, translated into English by a native American professional translator and back translated into Swedish by a bilingual Swedish psychologist. The similarity of these two Swedish versions was judged to be satisfactory by the constructors of the scale. Subsequent testing was performed with the original Swedish version. A French version has been produced in the same way and a Dutch translation is on-going. (For information about these versions, please contact the authors.)

Participants

KEDS was evaluated using ratings from 203 patients diagnosed with ED and 117 healthy control subjects. All participants gave their informed consent to the study. The patients were 34 sick-listed individuals who were recruited to an intervention study at the Karolinska Institute during 2005–2006, and 169 patients who were referred to a stress rehabilitation clinic by their general practitioners during 2008–2010. All patients fulfilled the criteria for ED (Table1), either with or without symptoms of depression and/or anxiety, as examined by a psychiatrist or a rehabilitation physician and psychologist. Three patients’ ratings were incomplete and were excluded, thus 200 patients were included in the analysis.

The 117 comparison individuals were randomly selected during 2009 and 2010 from the population in the County of Stockholm, by Statistics Sweden (SCB). The aim was to obtain a similar age distribution as that of clinical ED patients but with a slight over representation of men compared to typical ED since the group was also meant to be used as controls for a subsequent study of heart disease. All controls were in good physical and mental health as assessed by a psychiatrist (MÅ) or a trained physician (ÅN), using a clinical interview schedule (M.I.N.I.; Sheehan, Lecrubier Sheehan et al., 1998; Allgulander, Wærn, Humble, Andersch & Ågren, 2009). None of the controls met DSM-IV criteria for a history or current psychiatric disorder, personality disorder or severe somatic illness. The controls were 25–55 years old and worked full- or part-time.

Measures

KEDS was distributed prior to treatment (patients), or on study inclusion (controls). On the same occasion, all subjects rated themselves on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale (HAD). The HAD was developed for assessing clinically significant degrees of anxiety (HAD-A) and depression (HAD-D) (Zigmond & Snaith, 1983). A review of 71 articles, including somatic, psychiatric and primary care patients and the general population samples, found that both HAD-subscales performed well in assessing symptom severity (Bjelland, Dahl, Haug & Neckelmann, 2002). For both HAD scales, a score of 8–10 is defined as doubtful caseness, while 11 or more is defined as definite caseness (Zigmond & Snaith, 1983). The HAD consists of 14 items, seven reflecting anxiety and seven for depression. The items regarding the anxiety scale are the uneven numbers and depression are the even numbers. In our patient group Cronbach’s alpha was 0.78 for HAD-D and 0.82 for HAD-A, and 0.74 and 0.76, respectively, in the healthy control group.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive characteristics were compared between patients and controls using independent sample T-test for age, and chi-square (or the Fisher exact test when the expected count was less than 5) for gender proportions and educational level.

KEDS ratings were analysed at item-level and for summated scores. According to Curran, Finch & West (1996) the assumption of normal distribution is severely violated if skewness > 2 and kurtosis > 7.

The differences in KEDS scores at item- and total sum-level between groups and genders were examined using non-parametric independent-sample median test. The diagnostic validity was also assessed by analyses of summated scores using receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve, using clinically evaluated exhaustion disorder as gold standard. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) with varimax rotation was used in order to explore dimensionality of KEDS. Internal consistency was evaluated by the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient.

Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFA) with Full Information Maximum Likelihood estimation (FIML) was conducted using Amos 21 software (IBM, Chicago, IL). Besides χ2, model fit was assessed with the Bentler-Bonnett Normed Fit Index (NFI), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). According to Hu and Bentler (1999), a NFI and CFI value above 0.95, and a RMSEA value below 0.05, indicate close fit. The following models were assessed: (1) All three latent variables – ED, anxiety, and depression – were collapsed to one latent variable; (2) ED and anxiety were collapsed to one latent variable while depression was treated as a separate latent variable; (3) ED and depression were collapsed and anxiety was treated as separate; (4) Anxiety and depression were collapsed and ED was treated as separate; and (5) All three latent variables were treated as separate. These five models were assessed either using the full sample (A1–A5) or only the patients (P1–P5). The significance of the difference in fit between some nested models was tested by subtracting their χ2-values (Δχ2). In order not to violate assumptions of normality, parameter values were calculated in 5,000 bootstrap samples. As bootstrapping in Amos cannot be conducted with missing data, these (not more than 3 on any item) were replaced through linear interpolation.

Ethics

The studies were approved by the Ethics committee at the Karolinska Institute.

Results

Descriptive characteristics

Descriptive characteristics are presented in Table2. Neither age nor educational level differed significantly between groups. As planned the proportion of men was higher in the control group than in the patients.

Table 2.

Characteristic of patients and controls at the time of inclusion.Proportions of doubtful and definite cases of HAD-A and HAD-D, according to the cut-off values suggested by Zigmond & Snaith (1983)

| Patients, n = 200 | Controls, n = 117 | p for difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age years – Mean (s.d.) | 45.4 (8.6) | 45.2 (7.0) | 0.836 |

| Range years | 25 - 64 | 25 - 55 | - |

| Women, n (%) | 176 (88.0) | 79 (67.5) | 0.050 |

| Educational level: | |||

| Compulsory school, n (%) | 9 (4.5) | 6 (5.1) | 0.804 |

| Upper secondary school, n (%) | 62 (31.0) | 36 (30.8) | 0.972 |

| University, n (%) | 127 (63.5) | 75 (64.1) | 0.948 |

| Data not available, n (%) | 2 (1.0) | - | - |

| Sick-leave at inclusion: | n = 197 | n = 117 | |

| Full-time, n (%) | 132 (67.0) | - | - |

| Sick leave 25 – 75%, n (%) | 63 (32.0) | - | - |

| Sick leave 0%, n (%) | 2 (1.0) | 117 (100.0) | < 0.001 |

| HAD, subscale Anxiety | n = 194 | n = 117 | |

| Individuals scoring ≥ 8 and ≤ 10, n (%) | 50 (25.8) | 5 (4.3) | < 0.001 |

| Individuals scoring ≥ 11, n (%) | 105 (54.1) | 2 (1.7) | < 0.001 |

| HAD, subscale Depression | n = 194 | n = 117 | |

| Individuals scoring ≥ 8 and ≤ 10, n (%) | 69 (35.6) | 5 (4.3) | < 0.001 |

| Individuals scoring ≥ 11, n (%) | 89 (45.9) | 0 (0.0) | < 0.001 |

Explorative factor analysis and reliability

An explorative factor analysis of KEDS in the full sample revealed one factor with eigenvalue > 1 (6.11, explaining 67.87% of the total variance in the nine items) indicating unidimensionality of the scale. The factor loadings varied between 0.66 (item 9, irritation and anger) and 0.92 (item 4, mental stamina).

Separate analyses for the patients and the controls yielded two factors with eigenvalues > 1 in each subsample. The factor structure, after varimax rotation, was, however, not consistent in the two subsamples, and a decision was taken to regard KEDS as a unidimensional scale (data available on request). This decision was supported by scree plots. Internal consistency was acceptable with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.94 in the full sample, 0.74 in patients, and 0.81 in controls.

Diagnostic validity

Each item-score was increased in patients (p < 0.01), indicating that no item was irrelevant.

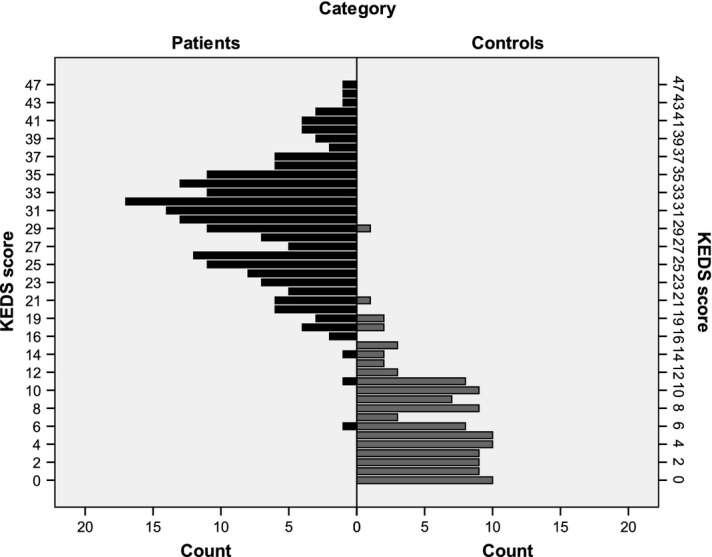

The distributions of KEDS summated scores across groups are presented in Fig.1. Summated scores in the patient group formed a bell-shaped distribution. A majority of the ratings performed by healthy individuals, gathered at very low scores forming a positively skewed distribution.

Figure 1.

Distribution of summated scores as assessed by the KEDS-scale in ED-patients (n=200) and in controls (n=117).

ROC coordinates are shown in Table3. The discriminative ability of KEDS was very good as demonstrated by the AUROCC (> 0.99, p < 0.01, 95% CI 0.982; 1.000), indicating that an individual with ED would reach higher scores than a person without ED, with a likelihood of approximately 99%. A cut-off score of 18.5 (in clinical practice rounded to 19) was considered appropriate with both sensitivity and specificity above 95%.

Table 3.

ROC-Coordinates showing scores with the best balance between sensitivity and specificity for the discrimination between ED patients and healthy controls on the KEDS and HAD subscales

| KEDS | HAD-D | HAD-A | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scores | Sensitivity | Specificity | Scores | Sensitivity | Specificity | Scores | Sensitivity | Specificity |

| All | ||||||||

| 17.0 | 97.5 | 94.9 | 4.5 | 95.9 | 82.9 | 5.5 | 90.2 | 86.3 |

| 18.5 | 95.5 | 96.6 | 5.5 | 92.3 | 88.0 | 6.5 | 85.1 | 89.8 |

| 19.5 | 94.0 | 98.3 | 6.5 | 86.6 | 94.9 | 7.5 | 79.9 | 94.0 |

| Women | ||||||||

| 17.0 | 98.3 | 97.5 | 4.5 | 97.2 | 84.8 | 5.5 | 90.3 | 86.1 |

| 18.5 | 96.0 | 97.5 | 5.5 | 93.2 | 89.9 | 6.5 | 84.7 | 91.1 |

| 19.5 | 94.3 | 98.7 | 6.5 | 86.9 | 97.5 | 7.5 | 80.1 | 94.9 |

| Men | ||||||||

| 17.0 | 91.7 | 89.5 | 4.5 | 87.5 | 78.9 | 5.5 | 91.7 | 86.8 |

| 18.5 | 91.7 | 94.7 | 5.5 | 83.3 | 84.2 | 6.5 | 87.5 | 86.8 |

| 19.5 | 91.7 | 94.7 | 6.5 | 83.3 | 89.5 | 7.5 | 79.2 | 92.1 |

Note: In both HAD subscales, non-caseness is defined by 0-7 according to Zigmond & Snaith (1983).

Although Table3 suggests that KEDS might have both higher sensitivity and higher specificity among women compared with men, separate analyses revealed that the discriminative ability was high in both genders (AUROCC for women = 0.99; p < 0.001; AUROCC for men = 0.98; p < 0.001).

Binary logistic regression analyses confirmed that KEDS scores have a positive association with the odds of being a patient both among women (the odds of being a patient increases with 70.1% for every increase in KEDS with one point, p < 0.001) and among men (an increase in the odds with 38.8% for every increase in KEDS with one point, p < 0.001). Gender was not a significant moderator of the associations between KEDS scores and the odds to be a patient (p = 0.114).

ROC analyses using both HAD scales (Table3), demonstrated that the best balanced sensitivity and specificity occurred on scores well below the threshold defining caseness suggested by Zigmond and Snaith (1983). In both HAD subscales, caseness is defined by a score of 10 and above.

Construct validity

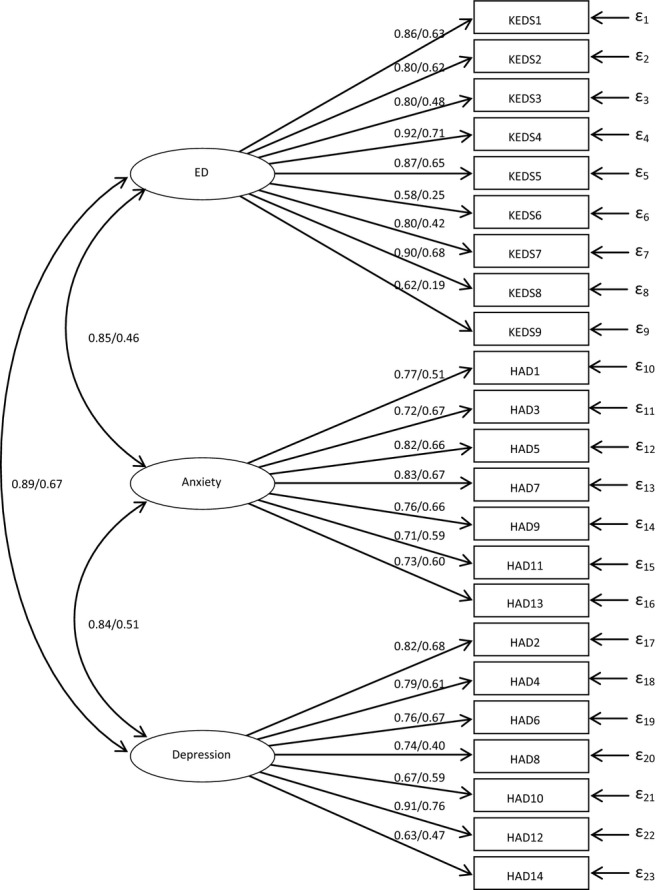

Model fit for the five models analyzed in the CFA are presented in Table4, separately for the full sample (N = 317) and for patients only (N = 200). The model fit was significantly better for the model with three separate latent variables, both for the full sample (A5 vs. A3, which has the second best fit, Δχ2 = 158, df = 2, p < 0.001), and for patients only (P5 vs. P3, Δχ2 = 85, df = 2, p < 0.001). Both for the full sample and for the patients, the model where all three latent variables are collapsed to 1 had the poorest fit. The fit of the model with three separate latent variables could be characterized as acceptable when using the full sample but not when using only the patients.

Table 4.

Model Fit for the Models with One to Three Latent Variables, Calculated on the Full Sample (A1-A5) or Only the Patients (P1-P5)

| Model | Collapsed | Not Collapsed | χ2 | Df | NFI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Allthree | None | 978 | 230 | 0.838 | 0.871 | 0.101 |

| A2 | ED and Anxiety | Depression | 836 | 229 | 0.862 | 0.895 | 0.092 |

| A3 | ED and Depression | Anxiety | 759 | 229 | 0.875 | 0.908 | 0.086 |

| A4 | Anxiety and Depression | ED | 808 | 229 | 0.867 | 0.900 | 0.089 |

| A5 | None | Allthree | 601 | 227 | 0.901 | 0.935 | 0.072 |

| P1 | Allthree | None | 732 | 230 | 0.545 | 0.623 | 0.105 |

| P2 | ED and Anxiety | Depression | 642 | 229 | 0.601 | 0.690 | 0.095 |

| P3 | ED and Depression | Anxiety | 553 | 229 | 0.657 | 0.757 | 0.084 |

| P4 | Anxiety and Depression | ED | 640 | 229 | 0.603 | 0.692 | 0.095 |

| P5 | None | Allthree | 468 | 227 | 0.710 | 0.820 | 0.073 |

The parameter values, calculated through bootstrapping, for the model with three separate latent variables, are presented in Fig.2. It can be noted that all values are higher when using the full sample than when using only the patients. When using only the patients, a few loadings are quite low, especially those for KEDS 6 (sleep) and KEDS 9 (irritation and anger).

Figure 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis of scores on scales assessing ED (KEDS), depression and anxiety (HAD). Parameter values for the model with three separate latent variables. The first parameter value has been calculated using the full sample and the second value has been calculated using only the patients. All parameters are significant (p < 0.02).

Discussion

A nine item summated self-rating scale, the Karolinska Exhaustion Disorder Scale (KEDS), for assessment of symptoms of stress-induced exhaustion disorder (ED, also known as chronic stress disorder, or clinical or severe burnout), was developed and evaluated. The scale was unidimensional and internally consistent, and discriminated between ED patients and healthy controls with a specificity and sensitivity exceeding 95% at a cut-off score of 19 (total range 0–54).Confirmatory factor analysis supports the idea of ED as a separate disorder, albeit there are associations between KEDS and measures of depression and anxiety.

Respondent feedback indicated that the scale was easy to use, and may improve patient understanding of ED symptomatology. The symptoms of other prolonged fatigue states, for instance the chronic fatigue syndrome, as well as neurasthenia (Hickie, Hadzi-Pavlovic & Ricci, 1997), are quite similar to exhaustion disorder, and it is possible that KEDS could be useful for research in these conditions as well, although this remains to be shown. Whether these syndromes are actually identical or overlapping conditions is outside the scope of the present study, but an interesting research question.

Our study shows that ED, depression- and anxiety-related conditions have an amount of shared variance in patients currently suffering from ED. Forty six percent of our patients with ED could also be classified as definite cases of depression on the HAD-D using the established caseness definition (Zigmond & Snaith, 1983), but the optimal HAD-D cut off scores between patients and controls in the ROC analyses lay well below the caseness definition.

The confirmatory factor analyses further strengthened the conclusion that ED, depression, and anxiety are distinct conditions. When using data from patients only, model fit and parameter values decreased compared to the full sample (Table3, Figure2). This could be due to a bimodal distribution on the manifest variables in the full sample, which would tend to inflate the strength of observed associations, although the bootstrapping method we used is not based on assumptions of normality. However, although the model fit was mediocre in the group of patients, it was still significantly better when ED, depression and anxiety were defined as three separate constructs.

Most items performed well in the confirmatory factor analyses, but two of them – sleep, and irritation and anger, loaded weakly on the latent variable (ED) in the patient group. A possible explanation may be that ED patients can have different types of sleep disorders. While the most common disturbance is difficulties falling asleep and restless, brief sleep, some may have very long duration of sleep and still wake up feeling unrested. The sleep item in KEDS reflects the first type of sleep disorders. Irritation and anger is, according to clinical experience, a characteristic feature of the early phases in ED and often disappears with increasing duration of the disorder. Taken together, these items contribute to the distinction between pathological exhaustion and normal tiredness, but may not reflect severity of ED. The formulations of response alternatives to both items will be slightly revised in further editions of the scale.

Sick listed patients treated for depression with drugs or psychotherapy quite often experience difficulties returning to work, even after their depressive symptoms are relieved (Adler, Adler, McLaughlin et al., 2006; Bryngelson et al., 2012). We suggest that exhaustion symptoms, which may have a longer duration than depressive symptoms, may partly account for this and that KEDS might yield useful information in such cases. Together with validated scales for assessment of depression and anxiety, KEDS could be used in clinical trials and possibly explain the absence of desirable effects of antidepressant medication in some cases.

Another possible use for KEDS is in screening for signs of exhaustion at work. It has been shown that chronic stress among health care personnel may be preventable, if cases at risk are identified at an early stage (Peterson, Bergström, Samuelsson, Åsberg & Nygren, 2008). KEDS is currently included in a screening questionnaire used in an on-going occupational health survey.

Since we have so far only studied the discrimination between ED patients and healthy controls, we do not know whether KEDS has sufficient discriminant validity to aid in differential diagnosis between different disorders. Patients with major depressive disorder may well reach high scores on KEDS, although the symptom profile may differ from ED. This issue remains to be studied.

So far, KEDS has not been compared with other scales developed for prolonged fatigue or stress induced disorders, such as the Schedule of Fatigue and Anergia (SOFA) (Hadzi-Pavlovic, Hickie, Wilson, Davenport, Lloyd & Wakefield, 2000), the stress-related Exhaustion Disorder (s-ED) scale (Glise et al., 2009), and the Karolinska Exhaustion Scale (KES, Saboonchi et al., 2012). Such studies are currently underway.

The sharp discrimination between controls and patients in our study suggests that KEDS will be useful for distinguishing between cases of normal tiredness and ED, and for identifying employees at risk for ED. A recently completed study shows that KEDS is sensitive enough to reflect effects of treatment and rehabilitation in ED (Besèr, Borg, Herlin, Nygren & Åsberg, 2013).

Appendix

References

- Adler D, Adler DA, McLaughlin TJ, Rogers WH, Chang H, Lapitsky L. Lerner D. Job performance deficits due to depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1569–1576. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.9.1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allgulander C, Wærn M, Humble M, Andersch S. Ågren H. 2009. Stockholm /Göteborg Karolinska Institutet,Sahlgrenska akademin & Mini Internationell Neuropsykiatrisk Intervju (Swedish version 6.0.0b).

- Åhsberg E, Gamberale F. Kjellberg A. Perceived quality of fatigue during different occupational tasks: Development of a questionnaire. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics. 1997;20:121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Åsberg M, Montgomery SA, Perris C, Schalling D. Sedvall G. A comprehensive psychopathological rating scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1978;271:5–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1978.tb02357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Åsberg M, Nygren Å, Leopardi R, Rylander G, Peterson U. Wilczek L. Novel biochemical markers of psychosocial stress in women. PLoS One. 2009;4:e3590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besèr A, Borg K, Herlin R-M, Nygren Å. Åsberg M. 2013. Group therapy, basic body awareness and mindfulness meditation in job-stress induced exhaustion disorder. A randomised, controlled rehabilitation study. In preparation.

- Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT. Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;52:69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blix E, Perski A, Berglund H. Savic I. Long-term occupational stress is associated with regional reductions in brain tissue volumes. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64065. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryngelson A, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Jensen I, Lundberg U, Åsberg M. Nygren Å. Self-reported treatment, workplace-oriented rehabilitation, change of occupation and subsequent sickness absence and disability pension among employees long-term sick listed for psychiatric disorders: A prospective cohort study. BMJ open. 2012;2 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001704. PubMed PMID: 23117569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho HJ, Skowera A, Cleare A. Wessely S. Chronic fatigue syndrome: An update focusing on phenomenology and pathophysiology. Current opinion in Psychiatry. 2006;19:67–73. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000194370.40062.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Finch JF. West SG. The robustness of test statistics to non normality and specification error in Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ekstedt M, Söderström M. Åkerstedt T. Sleep physiology in recovery from burnout. Biological Psychology. 2009;82:267–273. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberger HJ. Staff ‘burnout’. Journal of Social Issues. 1974;30:159–165. [Google Scholar]

- Gizatullin R, Zaboli G, Jonsson EG, Åsberg M. Leopardi R. The tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH) 2 gene unlike TPH-1 exhibits no association with stress-induced depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2008;107:175–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass DC. McKnight JD. Perceived control, depressive symptomatology, and professional burnout: A review of the evidence. Psychology and Health. 1996;11:23–48. [Google Scholar]

- Glise K, Hadzibajramovic E, Jonsdottir IH. Ahlborg G., Jr Self-reported exhaustion: A possible indicator of reduced work ability and increased risk of sickness absence among human service workers. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 2009;83:511–520. doi: 10.1007/s00420-009-0490-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossi G, Perski A, Ekstedt M, Johansson T, Lindström M. Holm K. The morning salivary cortisol response in burnout. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2005;59:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Hickie IB, Wilson AJ, Davenport TA, Lloyd AR. Wakefield D. Screening for prolonged fatigue syndromes: Validation of the SOFA scale. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2000;35:471–479. doi: 10.1007/s001270050266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickie I, Hadzi-Pavlovic D. Ricci C. Reviving the diagnosis of neurasthenia. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:989–994. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797004893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L. Bentler PM. Cut off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Järvisalo J, Andersson B, Boedeker W. Houtman I. Mental disorders as a major challenge in prevention of work disability. Helsinki: KELA; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic H, Perski A, Berglund H. Savic I. Chronic stress is linked to 5-HT(1A) receptor changes and functional disintegration of the limbic networks. Neuroimage. 2011;55:1178–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C. Burnout. The cost of caring. Englewood Cliffs. NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C. Jackson SE. Maslach burnout inventory manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Melamed S, Kuschnir T. Shirom A. Burnout and risk-factors for cardiovascular diseases. Behavioral Medicine. 1992;18:53–60. doi: 10.1080/08964289.1992.9935172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perski A. Grossi G. Treatment of patients on long-term sick leave because of stress-related problems. 2004. pp. 1295–1298. Results from an intervention study. Läkartidningen. [PubMed]

- Peterson U, Bergström G, Samuelsson M, Åsberg M. Nygren Å. Reflecting peer-support groups in the prevention of stress and burnout: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008;63:506–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydmark I, Wahlberg K, Ghatan PH, Modell S, Nygren A, Ingvar M, Asberg M. Heilig M. Neuroendocrine, cognitive and structural imaging characteristics of women on longterm sick leave with job stress-induced depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;60:867–873. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saboonchi F, Perski A. Grossi G. Validation of Karolinska Exhaustion Scale: Psychometric properties of a measure of exhaustion syndrome. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01089.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandström A, Rhodin IN, Lundberg M, Olsson T. Nyberg L. Impaired cognitive performance in patients with chronic burnout syndrome. Biological Psychology. 2005;69:271–279. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli W. Enzmann D. The burnout companion to study and practice. A critical analysis. In: Griffiths A, editor; Cox T, editor. Issues in occupational health. London: Taylor & Francis; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R. Dunba rGC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV andICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry; 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swedish Social Insurance Agency (Försäkringskassan) 2010. Långtidssjukskrivna. Beskrivande statistik 1999–2009: kön, ålder, arbetsmarknadsstatus, sjukskrivningslängd och diagnospanorama. (Socialförsäkringsrapport 2010:16)

- Wahlberg K, Ghatan PH, Modell S, Nygren Å, Ingvar M, Åsberg M. Heilig M. Suppressed neuroendocrine stress response in depressed women on job-stress-related long-term sick leave: a stable marker potentially suggestive of preexisting vulnerability. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;65:742–747. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winwood PC, Winefield AH, Dawson D. Lushington K. Development and validation of a scale to measure work-related fatigue and recovery: The Occupational Fatigue Exhaustion/Recovery Scale (OFER) [Validation Studies] Journal of occupational and environmental medicine / American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2005;47:594–606. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000161740.71049.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaboli G, Jonsson EG, Gizatullin R, De Franciscis A, Åsberg M. Leopardi R. Haplotype analysis confirms association of the serotonin transporter (5-HTT) gene with schizophrenia but not with major depression. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2008;147:301–307. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond AS. Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]