Abstract

Little is known about how special education services received by students with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASDs) differ by age, disability severity, and demographic characteristics. Using three national datasets, the Pre-Elementary Education Longitudinal Study (PEELS), the Special Education Elementary Longitudinal Study (SEELS), and the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS2), this study examined the age trends in special education services received by students with ASDs from preschool through high school. Elementary-school students with ASDs had higher odds of receiving adaptive physical education, specialized computer software or hardware, and special transportation, but lower odds of receiving learning strategies/study skills support than their preschool peers. Secondary-school students had lower odds of receiving speech/language or occupational therapy and of having a behavior management program, but higher odds of receiving mental health or social work services than their elementary-school peers. Both disability severity and demographic characteristics were associated with differences in special education service receipt rates.

Keywords: autism, special education, service, age, disability severity, demographic characteristics

Introduction

The diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASDs) has steadily increased in the United States in recent years (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012) and has been accompanied by a plethora of services and supports to treat its symptoms (Goin-Kochel, Myers, & Mackintosh, 2007). Schools are centrally important to families of a child with an ASD, as school services often are the most readily available, and schools can be the vehicle through which outside services are obtained (White, Scahill, Klin, Koenig, & Volkmar, 2007). Schools and their special education services can be seriously challenged as they seek to support the needs of the steadily growing number of students with ASDs (Yeargin-Allsopp et al., 2003).

Many prominent symptoms of ASD, such as difficulties with communication and social interaction and fixed and repetitive thinking and behavior, can limit functioning at school. In addressing the pervasive nature of ASD symptoms, schools often provide a combination of communication, social, and behavioral services and life skills training to help students succeed at school (Spann, Kohler, & Soenksen, 2003). However, little is known about the specific special education services students with ASDs receive from preschool through high school. No studies have yet examined differences in their receipt of special education services across this wide age span nor examined its relationship to disability severity and demographic characteristics, particularly using nationally representative data.

Documenting the pattern of services received by students with ASDs across childhood using national data will help policymakers, school personnel, and service providers project staffing and training needs to meet service demands as the population of students with ASDs continues to grow. Such data also provide a yardstick against which families can assess their own service experiences and gain new awareness of ways in which services might be broadened or reshaped to meet their children’s needs. Further, an awareness of changes in service receipt patterns associated with a move from preschool to elementary school and elementary to high school can help parents and educators prepare for that transition and possible alterations in the nature and level of services typically provided to children at the next school level. Understanding correlates of service receipt can help identify underserved groups of students with ASDs and help parents and other stakeholders identify and address special education access and equity issues.

What We Know

Families affected by ASD seek out and/or accept a wide array of services and treatments for their children (Dymond, Gilson, & Myran, 2007; Goin-Kochel et al., 2007; Hume, Bellini, & Pratt, 2005). For example, using information from 552 families about 111 different services and treatments, Green and colleagues learned that families were using an average of seven at the time they were surveyed, with one parent using 47 simultaneously (Green et al., 2006). Goin-Kochel and colleagues found that parents of individuals with ASDs ages 1.7 to 21.9 years old reported using between four and six therapies at the time they were surveyed and had tried between seven and nine therapies at some point in their children’s treatment histories (Goin-Kochel et al., 2007).

Further, service receipt by students with ASDs differs with age. For example, although several studies suggest that speech and occupational therapies are the most-used services across the age range (Bitterman, Daley, Misra, Carlson, & Markowitz, 2008; Hume et al., 2005; Thomas, Morrissey, & McLaurin, 2007; White et al., 2007), others note that the use of these services declines over time (Goin-Kochel et al., 2007). White et al., surveying 101 parents of children ages 9 through 15 with ASDs on children’s educational histories from kindergarten through eighth grade, found that rates of service receipt were highest in third and fourth grades and lowest in eighth grade (White et al., 2007). In a 2-year follow-up study of preschool children with ASDs, McConachie and Robinson (2006) found that as children aged, they had less involvement in services from agencies outside of school. Kurth and Mastergeorge (2010) reviewed the cumulative Individual Education Plans (IEPs) of middle school students with ASDs and learned that they received more curricular adaptations in middle school than they had in elementary school. Further, in middle school, they were more likely to receive behaviorist and para-educator supports, whereas in elementary school they were more likely to receive occupational therapy. These results suggest that educational priorities shift as students enter adolescence and that age appears to influence students’ experiences of services and supports.

Service receipt also varies with the nature and severity of students’ disabilities. For example, Bitterman et al. (2008) found that preschool children with ASDs received more services and more intensive services than children with other kinds of disabilities. White et al. (2007) found that among high-functioning first-grade students with ASDs, students with greater symptom severity received more services than their peers with less severity. Shattuck et al. (2011) also found more severe disability to be associated with higher rates of service receipt among young adults with ASDs.

Studies also indicate that the services used by students with ASDs differ along demographic lines. Mandell and colleagues (2002) found that Medicaid-eligible White children with ASDs received more services and at an earlier age than children with ASDs from a minority race/ethnicity. In a study of families with a child age 11 or younger with ASDs, Thomas and colleagues (2007) found that racial/ethnic minority families were less likely than their White peers to use services from a case manager, psychologist, or developmental pediatrician or receive sensory integration services. They also showed that parents with a college or graduate degree were more likely to use a neurologist for their child with an ASD than were less well-educated parents. Bitterman et al. (2008) also found that family income was negatively associated with receiving special transportation services.

Despite the variety of services available and accessed through and outside of schools, parents of children with ASDs often report that their service needs are unmet. In a survey in Virginia, Dymond et al. (2007) asked 929 parents of a child with an ASD (ages 0–22) how to improve services for their child, with responses indicating a need for (1) improved service quality, quantity, accessibility, and availability; (2) better training of nonprofessionals to work effectively with children with ASDs; (3) increased funding for services, staff development, and research; and (4) creation of appropriate school placements and educational programs for students with ASDs.

What We Need to Know

Despite what is already known about services provided to children with ASDs, there are a number of gaps in the literature that remain to be addressed. First, most studies have focused on a narrow age range of students with ASDs, particularly young children receiving early intervention services (Iovnannone, Dunlap, Huber, & Kincaid, 2003; Wilczynski, Menousek, Hunter, & Mugdal, 2007). No studies have yet looked across a child’s school career from pre-K through high school to identify differences and commonalities in service receipt. Second, most current studies focus on a wide range of therapies rather than the special education services provided to children with ASDs in schools. Third, these studies have limited generalizability due to small and nonrepresentative samples. This study addresses these weaknesses in the knowledge base by using three national longitudinal datasets to address the following questions: (1) What is the national picture of special education services provided to students with ASDs across the age range? (2) Do students whose disability, demographic, and family characteristics differ receive a different set of special education services?

Method

Study Databases

This study used the first wave of three national longitudinal datasets, the Pre-Elementary Education Longitudinal Study (PEELS), the Special Education Elementary Longitudinal Study (SEELS), and the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS2), to measure special education service receipt rates for students with ASDs from preschool through high school. PEELS followed a nationally representative sample of more than 3,000 children ages 3 through 5 across five waves of data collection from 2004 through 2009 (Carlson, Posner, & Lee, 2010). SEELS involved a nationally representative sample of more than 10,000 special education students ages 6 through 13, collecting data in 2000–01, 2001–02, and 2004–05 (Wagner & Blackorby, 2004; Wagner, Kutash, Duchnowski, & Epstein, 2005). The NLTS2 sample of more than 11,000 special education students ages 13 through 17 involved five waves of data collection, 2 years apart, from 2001 through 2009 (Wagner et al., 2005). The datasets have many similar design features, including data on common topics such as service receipt, using identical question language. By examining data from all three datasets, this study provides comparable snapshots of special education services received by students with ASDs ages 3 through 18.

Sample

All three datasets used the same two-stage sampling procedure to select nationally representative samples of students with disabilities. The first stage involved selecting local education agencies (LEAs) stratified by region, size (student enrollment), and wealth (percentage eligible for free/reduced price lunches), from which students receiving special education services in each disability category were randomly selected from the rosters of participating LEAs or special schools. This sampling procedure enables generalization of findings to the national population of students with ASDs as well as to students with disabilities as a whole and to those in each special education disability category (Carlson et al., 2010; Wagner & Blackorby, 2004; Wagner et al., 2005). PEELS, SEELS, and NLTS2 surveyed special educators regarding special education service receipt for 110, 690, and 580 students with ASDs at the first wave of data collection, respectively. Weights from wave 1 surveys in each of the three datasets were used to produce descriptive statistics that generalize to the national population of students receiving special education services under the ASD category.

The background characteristics of students with ASDs at wave 1 are depicted in Table 1. PEELS data include students in preschool (ages 3 through 5) in 2003–04, SEELS data include students in elementary and middle schools (ages 6 through 13) in 2000–01, and NLTS2 wave 1 data include students in middle and high schools (ages 13 through 17) in 2001–02.1 Students with ASDs represented in the datasets were disproportionately male (>83%) and White (>70%). More than 55% of students with ASDs had mothers with at least some college education, and a little less than half of the students were from families with annual incomes of $50,000 or more.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Students with ASDs Represented in PEELS, SEELS, and NLTS2

| Characteristic | PEELS Wave 1 2003–04 Preschool |

SEELS Wave 1 2000–01 Grade K-6 |

NLTS2 Wave 1 2001–02 Grade 7–10 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total unweighted N | 110 | 690 | 580 |

| Age | 3: 32.0% | 6: 1.7% | 13: 7.7% |

| 4: 41.8% | 7: 11.2% | 14: 25.2% | |

| 5: 26.3% | 8: 11.9% | 15: 23.0% | |

| 9: 16.7% | 16: 25.7% | ||

| 10: 14.1% | 17: 18.3% | ||

| 11: 18.3% | |||

| 12: 16.9% | |||

| 13: 9.2% | |||

| Male | 87.7% | 84.1% | 83.7% |

| Hispanic origin | 26.2% | 18.1% | 9.9% |

| Race | |||

| African American | 20.3% | 20.1% | 23.7% |

| White | 75.4% | 73.4% | 69.7% |

| Mixed/Other | 8.8% | 4.7% | 6.2% |

| Mother’s education | |||

| Less than high school | 14.9% | 15.8% | 6.9% |

| High school or GED | 25.7% | 29.0% | 22.9% |

| Some college | 15.5% | 30.2% | 36.9% |

| B.A./B.S. or higher degree | 43.9% | 25.0% | 33.2% |

| Annual income | |||

| <$25,000 | 29.6% | 22.7% | 21.7% |

| $25,001–50,000 | 25.5% | 30.9% | 28.8% |

| >$50,000 | 44.9% | 46.4% | 49.4% |

| Disability Severity Index (3–12) | 7.8 (0.16) | 5.4 (0.10) | 6.5 (0.11) |

| Communication (1-4) | 3.2 (0.06) | 1.8 (0.04) | 2.6 (0.07) |

| Understanding (1-4) | 2.3 (0.09) | 1.6 (0.03) | 2.0 (0.03) |

| Overall health (1-4) | 2.1 (0.13) | 2.1 (0.05) | 1.9 (0.05) |

| Family involvement in school | 2.4 (0.07) | 2.7 (0.06) | 2.4 (0.06) |

Note. Weighted means and standard errors in brackets are presented for continuous variables. Sample sizes are rounded to the nearest 10 in compliance with the Institute of Education Sciences requirements for analyzing restricted-use data.

Measures

The studies collected student data from multiple sources on a wide range of topics using parent/youth telephone interviews or mail surveys; school, teacher, and school program surveys; and in-person student assessments and interviews. The measures are described below.

Special education service receipt rates

The major outcome variables are whether a student with an ASD received a particular type of special education service and the total number of special education services that a student received. PEELS surveyed preschool teachers on whether a child received each type of service through the school system during the current school year, with a response rate of 74% (Carlson et al., 2010). SEELS and NLTS2 both surveyed school personnel knowledgeable about students’ programs to report on services included on a student’s IEP and provided to him/her by or through the school during the current school year, with response rates of 60% and 50%, respectively (Wagner & Blackorby, 2004; Javitz & Wagner, 2005). From a longer list of services, 14 special education services were analyzed if received by at least 15% of students with ASDs and for which the same wording was used in the three studies. These services were categorized as: (1) communication-related services, (2) behavioral health and life skills services, (3) learning supports, (4) technology aids, and (5) other services. A dummy variable was created to indicate whether a student with ASDs received none of three basic therapeutic services that particularly target ASD-related symptoms--speech/language and occupational therapies and behavior management services.

Demographic and family predictors

Across the datasets, student age in years and months was based on the date of the first wave of data collection. Parent interviews provided information on student gender, race/ethnicity, mother’s education level, and family income. Family involvement in school was calculated by summing four yes/no variables indicating whether the respondent or other family members had (1) attended a general school or program meeting, (2) attended a school or class event, (3) volunteered at school, and 4) attended an IEP meeting in the current school year. A summation of the scores produced a measure ranging from 0 to 4.

Disability-related predictors

Daley, Simeonsson, and Carlson (2009) and Bitterman et al. (2008) suggested creating a disability severity index from the PEELS dataset using parent-reported child functioning on six dimensions to measure the severity of children’s impairment. Because SEELS and NLTS2 surveyed three of the six dimensions that PEELS surveyed, a shortened disability severity index was created based on the three common dimensions across the datasets: communication/conversation, overall health, and ability to understand language. Parents rated students’ conversational ability as: 1=converses as well as others, 2=has a little trouble carrying on a conversation, 3=has a lot of trouble carrying on a conversation, or 4= does not converse at all. Parents rated a child’s ability to understand verbal or nonverbal communication as: 1=understands just as well as other children his/her age, 2= has a little trouble understanding, 3=has a lot of trouble understanding, or 4=does not understand at all. Children’s overall health was rated by parents as 1=excellent, 2=very good, 3=good, or 4=fair or poor. The disability severity index sums the three items and ranges from 3 to 12.

Analysis

All analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). SAS PROC SURVEY Taylor Series Linearization method was used to account for the complex sampling design and provide the exact estimate of the standard errors. This study used appropriate weights to produce summary statistics on the demographic, disability, and family variables and on service receipt rates. For multivariate models, PEELS, SEELS, and NLTS2 datasets were combined. Two dummy variables using elementary students with ASDs in the SEELS dataset as the reference group were created to indicate preschool students in PEELS and secondary students in NLTS2. Logistic regression models were used to predict the odds of receiving a particular special education service using measures of age group (preschool vs. elementary; secondary vs. elementary), demographics, disability severity, and family involvement at school. Interaction terms between age-group dummy variables and covariates were added to the main effect model one by one to test whether the effect of age group on the service rates changed depending on the level of covariates. Only significant interaction terms are presented in the results table. Multiple regression models were used to predict the number of services received using age group and the other covariates. These association analyses did not use sampling weights because weights from each dataset were not comparable.

Results

Services Received

Table 2 presents the weighted percentage of students with ASDs represented in each study who received each service. For preschool students with ASDs, the two most common special education services were speech/language and occupational therapies (85.2% and 65.3%). A behavior management program (44.6%), learning strategies/study skills support (44.3%), service coordination/case management (39.0%), and other communication services (38.1%) also were provided to more than one-third of students with ASDs. The use rates for the rest of the special education services ranged from 5.3% (mental health services) to 28.6% (special transportation).

Table 2.

Age Trends across PEELS, SEELS, and NLTS2 in Services Received by Students with ASDs

| Services | PEELS Wave 1 2003–04 Preschool |

SEELS Wave 1 2000–01 K-6 |

NLTS2 Wave 1 2001–02 7–10 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage receiving: | |||

| Communication-related services | |||

| Communication services | 38.1 | 17.2 | 21.7 |

| Speech/language therapy | 85.2 | 84.6 | 66.8 |

| Behavioral health and life skill services | |||

| Adaptive physical education | 17.3 | 39.1 | 50.9 |

| Behavior management program | 44.6 | 43.8 | 34.6 |

| Mental health services | 5.3 | 10.9 | 21.8 |

| Occupational therapy | 65.3 | 50.0 | 23.6 |

| Learning supports | |||

| Learning strategies/study skills | 44.3 | 29.5 | 21.6 |

| Tutoring by a special education teacher | 21.6 | 11.6 | 9.0 |

| Technology aids | |||

| Assistive technology services | 18.9 | 19.5 | 30.4 |

| Specialized computer software or hardware | 12.9 | 20.8 | 24.9 |

| Other services | |||

| Service coordination/case management | 39.0 | 39.5 | 44.7 |

| Special transportation | 28.6 | 44.7 | 54.0 |

| Social work services | 19.4 | 6.3 | 22.1 |

| Training, counseling, and/or services to the family | 30.4 | 12.1 | 25.6 |

| Received none of the three ASD-related servicesa | 18.0 | 3.4 | 6.7 |

| Mean number of services received | 4.7 (0.39) | 3.7 (0.10) | 3.9 (0.18) |

Note. Weighted means and standard errors in brackets are presented for continuous variables.

The three ASD-related services include speech/language and occupational therapies and behavior management

For elementary-school students with ASDs, speech/language therapy (84.6%) and occupational therapy (50.0%) also were the two most common special education services. Special transportation (44.7%), a behavior management program (43.8%), service coordination/case management (39.5%), and adaptive physical education (39.1%) also were commonly received by students with ASDs. Rates of receipt of less commonly provided services ranged from 6.4% for social work services to 29.5% for learning strategies/study skills support. Speech/language therapy also was the most common special education service provided to secondary-school students with ASDs, followed by special transportation (54.0%). Adaptive physical education (50.9%), service coordination/case management (44.7%), and a behavior management program (34.6%) also were fairly commonly provided to these students. Across the studies, 18.0% of preschool children with ASDs and 3.4% and 6.7% of elementary/middle and high school students received none of the three services that directly address ASD-related symptoms—speech/language and occupational therapies and behavior management services.

Predicting the Odds of Service Receipt

Tables 3 and 4 present the results from multiple logistic regression models and multiple linear regression models predicting the odds of receiving each special education service and the total number of special education services received by students with ASDs.

Table 3.

Predicting Communication, Behavioral Health and Life Skills, and Learning Support Service Receipt among Students with ASDs Represented in PEELS, SEELS, and NLTS2

| Communication-related services | Behavioral health and life skills services | Learning support services | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Predictors | Communication services | Speech/language therapy | Adaptive physical education | Behavior management program | Mental health services | Occupational therapy | Learning strategies/study skills support | Tutoring/remediation |

| Main effect | ||||||||

| PEELS | 1.62 [0.58,4.57] | 1.22 [0.41,3.67] | 0.14*** [0.06,0.34] | 1.21 [0.58,2.52] | 0.71 [0.14,3.67] | 1.45 [0.65,3.26] | 3.29** [1.51,7.16] | 1.16 [0.42,3.23] |

| NLTS2 | 0.80 [0.34,1.87] | 0.20*** [0.10,0.43] | 0.99 [0.54,1.81] | 0.50* [0.28,0.87] | 7.32*** [2.57,20.82] | 0.36** [0.19,0.67] | 0.76 [0.41,1.38] | 0.84 [0.35,2.04] |

| Age | 1.02 [0.89,1.17] | 1.04 [0.93,1.17] | 1.01 [0.91,1.11] | 1.04 [0.96,1.14] | 0.96 [0.82,1.14] | 0.95 [0.86,1.05] | 1.02 [0.93,1.12] | 0.92 [0.81,1.06] |

| Male | 0.95 [0.57,1.58] | 1.12 [0.72,1.74] | 0.66* [0.45,0.96] | 1.28 [0.90,1.84] | 1.54 [0.80,1.14] | 0.78 [0.53,1.15] | 1.24 [0.84,1.84] | 1.20 [0.68,2.11] |

| African American | 1.78* [1.13,2.80] | 1.20 [0.77,1.85] | 1.32 [0.92,1.89] | 0.72 [0.51,1.02] | 1.54 [0.80,2.99] | 0.90 [0.62,1.32] | 0.99 [0.69,1.42] | 0.96 [0.58,1.61] |

| Hispanic | 1.53 [0.90,2.58] | 1.23 [0.71,2.11] | 0.85 [0.55,1.32] | 0.77 [0.51,1.14] | 0.99 [0.49,2.03] | 0.84 [0.54,1.30] | 1.06 [0.70,1.61] | 0.89 [0.49,1.61] |

| Maternal education | 0.97 [0.78,1.20] | 1.03 [0.85,1.25] | 0.91 [0.78,1.07] | 1.03 [0.89,1.19] | 1.12 [0.86,1.47] | 1.05 [0.89,1.24] | 1.08 [0.93,1.27] | 1.04 [0.83,1.30] |

| Annual household income | 0.78* [0.61,1.00] | 0.79 [0.63,1.00] | 0.80* [0.66,0.96] | 0.97 [0.81,1.15] | 1.09 [0.79,1.50] | 1.44*** [1.18,1.76] | 1.03 [0.85,1.24] | 0.94 [0.72,1.22] |

| Communication | 2.37*** [1.85,3.03] | 1.77*** [1.39,2.26] | 1.68*** [1.38,2.04] | 1.30**[1.09,1.55] | 0.78 [0.58,1.06] | 1.35** [1.11,1.64] | 0.89 [0.74,1.09] | 1.15 [0.89,1.51] |

| Understanding | 0.88 [0.64,1.20] | 0.93 [0.68,1.27] | 1.04 [0.81,1.35] | 1.01 [0.80,1.27] | 0.63* [0.41,0.97] | 0.91 [0.70,1.18] | 1.02 [0.79,1.31] | 1.05 [0.75,1.49] |

| Overall health | 0.81* [0.66,0.99] | 0.87 [0.72,1.04] | 0.99 [0.85,1.35] | 1.08 [0.95,1.24] | 1.21 [0.95,1.54] | 0.93 [0.79,1.08] | 1.09 [0.94,1.27] | 1.07 [0.87,1.31] |

| Family school involvement | 0.92 [0.77,1.11] | 0.95 [0.80,1.12] | 0.90 [0.78,1.03] | 1.01 [0.89,1.15] | 1.09 [0.87,1.36] | 0.86* [0.75,1.00] | 1.14 [0.99,1.31] | 1.08 [0.88,1.32] |

|

| ||||||||

| Interaction effect between PEELS or NLTS2 and background covariates | ||||||||

| NLTS2* communication | 2.36*** [1.58,3.54] | 1.58** [1.15,2.17] | 1.98*** [1.36,2.89] | |||||

Note. Logistic regression models were performed using white, female, elementary students as the reference group. Odds ratio and associated confidence interval are presented for logistic regression models. Nonsignificant interaction terms are not presented.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001.

Table 4.

Predicting Technology Aids and Other Services Receipt among Students with ASDs Represented in PEELS, SEELS, and NLTS2

| Technology aids | Other services | Received none of the three basic servicesa | Number of services received | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Predictors | Assistive technology services | Specialized computer software or hardware | Service coor- dination/case management | Social work | Special transportation | Training, counseling, and services to the family | ||

| Main effect | ||||||||

| PEELS | 0.42 [0.17,1.04] | 0.26** [0.10,0.69] | 1.37 [0.65,2.91] | 2.57 [0.72,9.14] | 0.36** [0.17,0.77] | 2.76 [0.97,7.89] | 0.66 [0.16, 2.72] | 0.62 (0.37) |

| NLTS2 | 1.13 [0.58,2.21] | 0.83 [0.43,1.59] | 1.01 [0.57,1.78] | 5.47** [1.97,15.19] | 1.07 [0.61,1.86] | 1.91 [0.82,4.49] | 5.40*** [2.21, 13.18] | −0.24 (0.28) |

| Age | 1.01 [0.91,1.13] | 1.03 [0.93,1.14] | 1.03 [0.95,1.13] | 0.97 [0.83,1.14] | 1.03 [0.94,1.12] | 1.00 [0.87,1.15] | 0.95 [0.82, 1.09] | 0.01 (0.04) |

| Male | 1.25 [0.80,1.94] | 0.80 [0.54,1.20] | 1.70** [1.16,2.48] | 1.11 [0.63,1.96] | 0.98 [0.69,1.39] | 1.13 [0.67,1.89] | 0.88 [0.52, 1.49] | 0.13 (0.18) |

| African American | 0.99 [0.66,1.48] | 1.07 [0.72,1.58] | 0.70* [0.49,0.99] | 1.19 [0.71,1.99] | 0.94 [0.67,1.31] | 1.06 [0.66,1.72] | 1.03 [0.62, 1.71] | −0.11 (0.17) |

| Hispanic | 1.04 [0.65,1.68] | 1.42 [0.90,2.22] | 0.59* [0.39,0.90] | 1.14 [0.62,2.09] | 0.79 [0.53,1.17] | 1.44 [0.87,2.40] | 1.17 [0.62, 2.21] | −0.08 (0.20) |

| Maternal education | 1.01 [0.85, 1.21] | 1.05 [0.88,1.25] | 1.05 [0.90,1.22] | 0.93 [0.73,1.19] | 0.85* [0.73,0.98] | 1.07 [0.87,1.31] | 1.07 [0.84, 1.35] | 0.02 (0.07) |

| Annual household income | 1.03 [0.83,1.27] | 0.87 [0.71,1.06] | 1.13 [0.94,1.35] | 0.87 [0.65, 1.16] | 0.70*** [0.59,0.84] | 1.01 [0.79,1.30] | 1.20 [0.90, 1.59] | −0.07 (0.09) |

| Communication | 1.60*** [1.31,1.97] | 0.38** [1.13,1.69] | 1.08 [0.90,1.29] | 1.09 [0.83,1.42] | 1.45*** [1.21,1.74] | 1.03 [0.81,1.31] | 0.61*** [0.45,0.81] | 0.57*** (0.09) |

| Understanding | 0.91 [0.69,1.19] | 0.97 [0.74,1.27] | 1.00 [0.78,0.27] | 1.06 [0.74,1.51] | 0.86 [0.68,1.09] | 0.97 [0.70,1.33] | 1.18 [0.80, 1.74] | −0.11 (0.12) |

| Overall health | 1.06 [0.90,1.25] | 0.95 [0.81,1.12] | 1.05 [0.91,1.21] | 0.99 [0.80,1.24] | 0.95 [0.82, 1.08] | 0.96 [0.79,1.16] | 1.09 [0.88, 1.35] | −0.02 (0.07) |

| Family school involvement | 0.87 [0.74,1.01] | 0.83* [0.72,0.97] | 0.92 [0.80,1.05] | 0.85 [0.70,1.03] | 1.04 [0.92,1.19] | 0.94 [0.79,1.13] | 1.04 [0.86, 1.27] | −0.08 (0.06) |

|

| ||||||||

| Interaction effect between PEELS or NLTS2 and background covariates | ||||||||

| NLTS2*communication | 0.41*** [0.25, 0.65] | |||||||

Note. Logistic regression models were performed using white, female, elementary students in SEELS data as the reference group for all outcomes except counts of total services received. Odds ratio and associated confidence interval are presented for logistic regression models. Multiple regression models were performed for counts of total services received outcomes, and coefficients and associated standard errors are presented. None of the interaction terms were significant and they were not presented here.

Three basic services include speech/language therapy, occupational therapy, and behavior management.

Age cohort

Compared with elementary-school students with ASDs, preschool students with ASDs had significantly lower odds of receiving adaptive physical education, specialized computer software or hardware, and special transportation, but significantly higher odds of receiving learning strategies/study skills supports, controlling for demographic characteristics, disability severity, and family involvement. Compared with elementary-school students with ASDs, secondary-school students had lower odds of receiving speech/language therapy, having a behavior management program, and receiving occupational therapy, but higher odds of receiving mental health and social work services. Within each study cohort, age was unassociated with service receipt rates, controlling for other factors.

Demographic differences

Male students with ASDs were less likely to receive adaptive physical education but more likely to receive service coordination/case management services than their female peers. Compared with White students with ASDs, African American students had higher odds of receiving communication services but lower odds of receiving service coordination/case management services. Hispanic students with ASDs differed from their White peers only in having lower odds of receiving service coordination/case management services. Mother’s education level was negatively associated with the odds of receiving special transportation services. Household income was negatively associated with the odds of receiving communication services, adaptive physical education, and special transportation services, but positively associated with the odds of receiving occupational therapy.

Disability severity

Compared with students with ASDs who were less impaired in communication/conversation skills, those who were more impaired not only had higher odds of receiving 8 of the 14 special education services, but also of receiving a greater number of special education services. Students with ASDs with more difficulty in understanding verbal or non-verbal communications had lower odds of receiving mental health services, and those with more severe health problems had lower odds of receiving communication services than their peers whose communication and health were less impaired.

Family involvement at school was associated with lower odds of receiving occupational therapy and specialized computer software or hardware, controlling for other factors.

Interaction effects

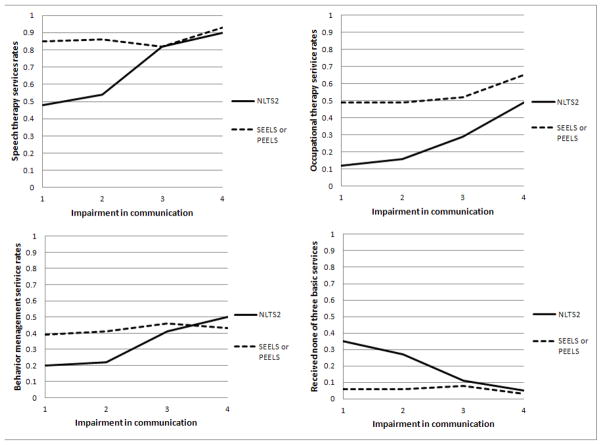

Significant interaction effects were found between being a high school student (as represented in NLTS2) and communication skills on the odds of receiving speech/language, occupational therapy, behavior management services, or none of these three services (Figure 1). Although secondary-school students with ASDs generally were less likely to receive these three services than their elementary-school peers, secondary-school students whose conversation abilities were severely impaired had similar odds of receiving these three services as their peers in elementary school.

Figure 1.

Interaction plots describing the effect of age group on odds of receiving speech or language therapy, behavior management service, occupational therapy, or none of three basic therapeutic services depending on the severity of communication impairment.

Discussion

This study is the first to report special education service receipt rates for students with ASDs in preschool, elementary, and secondary school using three national datasets. The most common special education service received by students with ASDs in all three study cohorts was speech/language therapy; 85.2%, 84.6%, and 66.8% of students across the studies received this service. These proportions were similar to the 87% reported by Bitterman et al. (2008), 70% reported by Green et al. (2006), and 84% reported by Goin-Kochel et al. (2007), but much higher than the 37% reported by Hess and colleagues for a sample of students in Georgia public schools and much higher than the 9.1% of youth with ASDs who received that service once they had left high school (Shattuck et al., 2011). The second most common special education service for preschool and elementary students with ASDs was occupational therapy (65.3% and 50.1%), rates that are close to those reported by Bitterman et al. (2008) and Goin-Kochel et al. (2007) but again higher than Hess et al. (2008). The high proportion of students with ASDs receiving speech/language and occupational therapy are consistent with the severity of communication impairments and with the pervasive effects of ASDs on activities of daily living among many students with ASDs, challenges that may be ameliorated with these forms of therapy.

In contrast, our findings on the relatively lower rates of students with ASDs having a behavior management program (34.6% to 44.6% across studies), through which impulse control strategies and social skills, for example, could be taught, are inconsistent with the widespread social and behavioral impairments that are characteristic of ASDs. Nonetheless, inattention by schools to social and behavioral issues in serving students with ASDs has been reported in other research (Kohler, 1999; Kurth & Mastergeorge, 2010; White et al., 2007), leading White and colleagues to assert that it constitutes “an area of unmet need in schools” (p. 1410). Additionally, the finding that learning supports, including tutoring, were provided to relatively few elementary-school students with ASDs is consistent with contentions by others that providing academic interventions and supports is under-emphasized in developing IEPs for students with ASDs (Kurth & Mastergeorge, 2010; Shapiro, 2010; White et al., 2007), particularly in light of the increasing inclusion of such students in general education settings.

Interestingly, case management/service coordination was consistently provided for about 4 in 10 students with ASDs across the three studies, a rate that was maintained into the post-high school years (Shattuck et al., 2011). The relatively low rates of receipt of mental health services across the study cohorts (5.3% to 21.8%) was surpassed among young adults with ASDs in the early post-high school years (35.0%) (Shattuck et al., 2011).

The average number of special education services received by students with ASDs was 4.67, 3.65, and 3.88 for preschool, elementary-, and secondary-school students, respectively, which are lower than parent-reported average of 7.2 treatments found by Goin-Kochel et al (2007) and 7 services found by Green et al (2006). This may reflect the fact that the previous studies were based on parent reports and included treatments such as drug therapies along with services, whereas this study is based on school-reported, school-provided special education services and focused only on services received by at least 15% of students with ASDs.

The main findings of the study relate to age differences in special education service receipt. After controlling for demographic characteristics, disability severity, and family involvement, compared with elementary school students with ASDs, this study found that some service receipt rates declined with age. For example, elementary students with ASDs were less likely to receive learning strategies/study skills supports than preschool students with ASDs, even though they were tackling formal elementary-grade curriculum content that would not characterize preschool programs. Similarly, secondary-school students with ASDs were less likely to receive speech/language and occupational therapy, to have a behavior management program, and to receive none of the three basic therapeutic services than elementary-school students. The finding on the declining trends of speech/language and occupational therapy service rates are consistent with findings of Goin-Kochel et al (2007) and Kurth and Mastergeorge (2010). A decline in learning strategies/study skills services and having a behavior management program remain understudied. The finding on increasing trends of students with ASDs receiving none of the three basic therapeutic services indicate that accessing these essential supports through the special education system becomes more difficult as students age. Future research needs to focus on understanding barriers to continuity in accessing needed services throughout a student’s school career.

Different from several recent studies that found declining service receipt rates with age (Goin-Kochel et al., 2007; Kurth & Mastergeorge, 2010; Thomas, Morrissey, et al., 2007), this study found increasing service receipt rates for several special education services. Elementary-school students with ASDs had higher odds of receiving adaptive physical education, specialized computer software or hardware, and special transportation than their preschool peers, and secondary-school students with ASDs had higher odds of receiving mental health and social work services through their schools then their elementary-school peers.

Given the emphasis in IDEA on individualizing services and programs for students with disabilities, it is not surprising that a different pattern of services could emerge as children enter and exit different developmental stages. For example, adolescence is the time of onset for about half of life-time mental disorders in the general population (Kessler et al., 2007). Thus, it would be expected that mental health services would be more commonly provided in high schools than earlier, regardless of the presence of ASDs or other forms of disability. The family tensions that often increase as children reach adolescence also could be expected to generate an increased need for family-oriented social work services, as we see for students with ASDs represented in NLTS2. Similarly, elementary-school students would be more developmentally ready to handle school-provided bus or van transportation to school and to take advantage of educational software and hardware at school than preschoolers, with or without disabilities.

Differences in state policies governing elementary and secondary schools also might contribute to changes in students’ disability-related services. For example, the California State Board of Education mandates that secondary-school students receive twice as many minutes of physical education in a 10-day period as elementary school students (Office of Special Education Program, 2012). This would contribute to an increased need for adaptive physical education for older students with physical/coordination limitations relative to younger students, an increase found in this and other studies (Thomas, Ellis, et al., 2007). A next step in research is to study whether these differences in service patterns over time relate to differences in outcomes for students with ASDs.

Our results also indicate that student characteristics are associated with special education service receipt rates. They confirm findings from previous studies that more severely impaired students with ASDs received more services or therapies (Bitterman et al., 2008; Green et al., 2006), indicating that service provision is responsive to individual need, as intended by law. Although as a whole, secondary-school students with ASDs received less speech/language and occupational therapies and were less likely to have a behavior management program than their elementary-school peers, older students with ASDs who had more limited communication skills had similar odds of receiving these three interventions as their elementary-school peers, suggesting that allocation of speech/language services appropriately reflected student needs.

Although the association between family income and special education service receipt has rarely been studied, one previous study (Bitterman et al., 2008) was consistent with our findings that higher family income was associated with lower adjusted odds of receiving special transportation services, perhaps because higher-income families were more able to provide transportation for their children with an ASD themselves. The current study also found students with ASDs from higher-income families had lower adjusted odds of receiving communication services and adaptive physical education provided by their school but higher odds of receiving occupational therapy. Further research is needed to understand the reasons behind these income-related differences in special education service receipt rates. Hispanic and African American students with ASDs were found to have lower adjusted odds of receiving case management/case coordination services than their White peers, suggesting a need for further research focused on the special education service needs, special education access barriers, and equity of service receipt among minority students with ASDs.

This study has made an important contribution to our understanding of the patterns of services students with ASDs receive from or through their schools across the preschool-through-high school grade range. However, service receipt rates reveal little about a critical question in serving students with ASDs or any disability—are the services enough? Are there needs for services that are not being met? Although limited, some parent-reported data can be brought to bear on this question. Early interview- or survey-based studies of the views of parents with children with disabilities regarding the services they received suggested that obtaining services for their children required “fighting” for what children needed (McWilliam et al., 1995) and that they did not receive enough services (Dunlap, Robbins, & Darrow, 1994). A more recent study using PEELS data found that parents of preschool children with ASDs were significantly more likely to report dissatisfaction with the services their children received than were parents of children with other disabilities, even after controlling for severity of disability, total hours of services received, and the number of different services received. Almost half of parents of students with ASDs reported their children needed more of the services they were receiving and one-fourth indicated there were needed therapies or services that their children were not getting through their school district (Bitterman et al., 2008). NLTS2 included items similar to PEELS regarding parents’ satisfaction with their children’s services and had similar findings. High school students with ASDs were significantly more likely to have parents reporting that it took “a great deal of effort” to obtain services for them than did students with disabilities as a whole (32.5% vs. 18.7%, p < .001), and their parents were more than twice as likely to report that the services they received were insufficient to meet their needs (35.4% vs. 15%, p < .001) (Levine, Marder, & Wagner, 2004). Clearly, from the perspective of parents of students with ASDs, much remains to be done by their schools to meet their diverse service needs.

Although this study makes an important contribution to the literature, there are several limitations to consider when interpreting these findings. First, the studies’ survey instruments asked school staff to report services indicated on IFSPs or IEPs as being provided to specific students with disabilities; nonetheless, some school staff may have relied on individual knowledge of services provision rather than documentation, perhaps underreporting service receipt rates (Bhandari & Wagner, 2006). Second, the severity of disability was based on parent reports of the child’s communication/conversation skills, overall health, and ability to understand language. Parent-reported severity of disability may be subject to bias and cannot be equated with the results of formal evaluations conducted by trained professionals. Third, although the survey items cover a variety of special education services provided to students with ASDs, no definitions of those services were provided to respondents, and no information on procedures, quality, intensity, and fidelity of implementation of those services was collected. Thus, the actual experience involved in receiving a particular service is very likely to have differed, possibly widely. Further, the Office of Special Education Programs’ (OSEP) new vision for Results-Driven Accountability (RDA) shifts the focus from procedural compliance to improving results and outcomes for children with disabilities (Office of Special Education Program, 2012). This new shift indicates that future research is needed to advance our understanding of the effectiveness as well as quality and implementation of special education services and programs. Fourth, although this study used three national databases, our results can only provide a snapshot of the services received by each age group (i.e., preschool, elementary, secondary) in the early 2000s. Lastly, because the data do not permit linking students to their school and state locations, this study was not able to estimate the important state-to-state differences and high-SES -to-low-SES school differences in special education service receipt rates.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding to SRI International from the Institute of Education Sciences (R324A120012) and the National Science Foundation (HRD-1130088), and to Dr. Shattuck from Autism Speaks and the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH086489). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the National Science Foundation, the National Institute of Mental Health, or any other funders.

Footnotes

For simplicity, students represented in SEELS are referred to as elementary-school students and those represented in NLTS2 are referred to as secondary-school students.

Contributor Information

Xin Wei, Email: xin.wei@sri.com, Center for Education and Human Services, SRI International, 333 Ravenswood Avenue, BS169, Menlo Park, CA 94025-3493

Mary Wagner, Email: mary.wagner@sri.com, Center for Education and Human Services, SRI International, 333 Ravenswood Avenue, BS 154, Menlo Park, CA 94025-3493

Elizabeth R.A. Christiano, Email: elizabeth.riley@sri.com, Center for Technology in Learning, SRI International, 333 Ravenswood Avenue, BN267, Menlo Park, CA 94025-3493

Paul Shattuck, Email: pshattuck@wustl.edu, Washington University, Campus Box 1196, 1 Brookings Dr, St Louis, MO 63130

Jennifer W. Yu, Email: jennifer.yu@sri.com, Center for Education and Human Services, SRI International, 333 Ravenswood Avenue, BS162, Menlo Park, CA 94025-3493

References

- Bhandari A, Wagner T. Self-reported utilization of health care services: Improving measurement and accuracy. Medical Care Research and Review. 2006;63(2):217–235. doi: 10.1177/1077558705285298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitterman A, Daley T, Misra S, Carlson E, Markowitz J. A national sample of preschoolers with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Special education services and parent satisfaction. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38(8):1509–1517. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0531-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson E, Posner D, Lee H. Pre-Elementary Education Longitudinal Study Restricted-Use Data Set for Waves 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5: User’s Guide. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education: National Center for Special Education Research; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders —Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 14 sites, United States, 2008. MMWR. 2012;61(SS-03):1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley TC, Simeonsson RJ, Carlson E. Constructing and testing a disability index in a US sample of preschoolers with disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2009;31(7):538–552. doi: 10.1080/09638280802214352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap G, Robbins FR, Darrow M. Parents’ reports of their children’s challenging behaviors: Results of a state-wide survey. Mental Retardation. 1994;32:206–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dymond SK, Gilson CL, Myran SP. Services for children with autism spectrum disorders: What needs to change? Jounal of Disability Policy Studies. 2007;18(3):133–147. [Google Scholar]

- Goin-Kochel RP, Myers BJ, Mackintosh VH. Parental reports on the use of treatments and therapies for children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2007;1(3):195–209. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2006.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Green VA, Pituch KA, Itchon J, Choi A, O’Reilly M, Sigafoos J. Internet survey of treatments used by parents of children with autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2006;27(1):70–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess K, Morrier M, Heflin L, Ivey M. Autism treatment survey: Services received by children with Autism Spectrum Disorders in public school classrooms. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38(5):961–971. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0470-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hume K, Bellini S, Pratt C. The usage and perceived outcomes of early intervention and early childhood programs for young children with autism spectrum disorder. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2005;25(4):195–207. doi: 10.1177/02711214050250040101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iovnannone R, Dunlap G, Huber H, Kincaid D. Effective educational practices for students with autism spectrum disorders., 18(3), 150–165. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2003;18(3):150–165. doi: 10.1002/pits.20255. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, Ustun TB. Age of onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. Current Opinions in Psychiatry. 2007;20(4):359–364. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler FW. Examining the services received by young children with autism and their families: A survey of parent responses. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 1999;14(3):150–158. [Google Scholar]

- Kurth J, Mastergeorge AM. Individual education plan goals and services for adolescents with autism: Impact of age and educational setting. The Journal of Special Education. 2010;44(3):146–160. doi: 10.1177/0022466908329825. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levine P, Marder C, Wagner M. Services and supports for secondary school students with disabilities. A special topic report of findings from the National Longitudinal Transitioin Study-2 (NLTS2) Menlo Park, CA: SRI International; 2004. Retrieved from http://www.nlts2.org/reports/2004_05/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- Mandell DS, Listerud J, Levy SE, Pinto-Martin JA. Race differences in the age at diagnosis among medicaid-eligible children with autism. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41(12):1447–1453. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200212000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConachie H, Robinson G. What services do young children with autism spectrum disorder receive? Child Care, Health and Development. 2006;32(5):553–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliam RA, Lang L, Vandiviere P, Angell R, Collins L, Underdown G. Satisfaction and struggles: Family percenptions of early intervention services. Journal of Early Intervention. 1995;19:43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Results-driven Accountability in Special Education (2012).

- Shapiro ES. Academic skills problems: Direct assessment and intervention. 4. New York, NY: Guilford; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shattuck PT, Wagner M, Narendorf SC, Sterzing PR, Hensley M. Post–high school service use among young adults with an autism spectrum disorder. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2011;165(2):141–146. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spann SJ, Kohler FW, Soenksen D. Examining parents’ involvement in and perceptions of special education services. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2003;18(4):228–237. doi: 10.1177/10883576030180040401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas KC, Ellis AR, McLaurin C, Daniels J, Morrissey JP. Access to care for autism-related services. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37(10):1902–1912. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0323-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas KC, Morrissey JP, McLaurin C. Use of autism-related services by families and children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37(5):818–829. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0208-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner M, Blackorby J. Overview of findings from wave 1 of the Special Education Elementary Longitudinal Study (SEELS) Menlo Park, CA: SRI International; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner M, Kutash K, Duchnowski AJ, Epstein MH. The Special Education Elementary Longitudinal Study and the National Longitudinal Transition Study. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2005;13(1):25–41. doi: 10.1177/10634266050130010301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White SW, Scahill L, Klin A, Koenig K, Volkmar FR. Educational placements and service use patterns of individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;(37):1403–1412. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0281-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilczynski S, Menousek K, Hunter M, Mugdal D. Individualized Education Programs for youth with autism spectrum disorders. Psychology in the Schools. 2007;44(7):653–666. [Google Scholar]

- Yeargin-Allsopp M, Rice C, Karapurkar T, Doernberg N, Boyle C, Murphy C. Prevalence of autism in a U.S. metropolitan area. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289(1):49–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]