Abstract

Engaging men is a critical component in efforts to reduce intimate partner violence (IPV). Little is known regarding men’s perspectives of approaches that challenge inequitable gender norms, particularly in settings impacted by armed conflict. This article describes men’s experiences with a women’s empowerment program and highlights men’s perceptions of gender norms, poverty and armed conflict, as they relate to achieving programmatic goals. Data are from 32 Ivorian men who participated in indepth interviews in 2012. Interviews were undertaken as part of an intervention that combined gender dialogue groups for both women and their male partners with women’s only village savings and loans programs to reduce IPV against women. Findings suggested that in the context of armed conflict, traditional gender norms and economic stressors experienced by men challenged fulfillment of gender roles and threatened men’s sense of masculinity. Men who participated in gender dialogue groups discussed their acceptance of programming and identified improvements in their relationships with their female partners. These men further discussed increased financial planning along with their partners, and attributed such increases to the intervention. Addressing men’s perceptions of masculinity, poverty and armed conflict may be key components to reduce men’s violence against women in conflict-affected settings.

Introduction

Men’s use of violence against their female partners (i.e. intimate partner violence [IPV]) is a pervasive global health concern [1], as nearly one in three women have reported IPV victimization at some point in their life [2]. IPV and other forms of gender inequalities, such as exclusion of women and girls from economic and educational opportunities can have negative impacts on women’s health. Health impacts of gender inequalities include increased risk of poor maternal, reproductive and mental health outcomes [3, 4].

Engaging men and boys in challenging societal gender norms that perpetuate IPV and the substatus of women has been recognized as one critical component of efforts to reduce IPV and to improve the health of women and girls [5–7]. Gender transformative approaches, which are programs designed to challenge unequal gender norms and promote equality between men and women, have also been highlighted as an important strategy to improve men’s health [8–10] through challenging traditional masculine ideologies associated with poor health behaviors among men (i.e. multiple partnering) [11–13].

Gender transformative approaches that challenge inequitable gender norms have more recently been incorporated into traditionally women-centered economic empowerment efforts (e.g. programs that seek to enhance women’s power through social change processes, [14, 15] such as microcredit activities) [16, 17]. This has largely been in response to concerns about potential increases in women’s vulnerability to IPV as women gain greater access to financial resources [18, 19]. These potential increases in IPV against women have been posited to occur as men may use violence to reassert their own power and position in relationships with women [20, 21]. Moreover, solely increasing economic assets for women without addressing larger inequitable gender norms, may not directly equate in women’s increased decision making regarding the use of any newly acquired financial resources [22].

Despite growing emphasis placed on the importance of challenging gender inequities within the context of women only economic empowerment programs, very little research to date has been devoted to understanding men’s perspectives and experiences with such programming. As such, investigation into men’s perspectives and masculinity has been recommended as an area of inquiry, in order to bolster effectiveness of such programs [21]. Notably, even less work on men’s perspectives in gender transformative programming has been conducted in regions impacted by conflict. Increased understanding of men’s perspectives can help shape interventions to appropriately target men and employ implementation strategies that encourage adherence and engagement. Within Côte d’Ivoire, a West African country affected by recent armed conflict in the early 2000s and with election-related violence in 2010–2011, poverty, insecurity and breakdown of infrastructure may also intensify challenges for men in fulfilling their traditional roles as family providers. In such settings impacted by conflict, these economic threats to masculinity are among a myriad of other factors, such as normalization of violence against women or stigmatization of women survivors of violence that may also lead to increased IPV perpetration [23].

Intersectionality theory may illuminate how complex social identities of men, including masculinity, poverty, insecurity and ethnicity, may interplay among a group of conflict-affected men [10, 24]. Examining men’s experiences through this lens may elucidate potential structural factors that impact IPV perpetration [21] as analyses guided by intersectionality draws attention to the relationships between multiple forms of identity and criticizes isolating social categorizations from each other [25]. For instance, intersectionality theory recognizes inequalities within heterogeneous groups and allows researchers to identify similarities between men and women through other social identities rather than only a woman/man dichotomy [25, 26]. Intersectionality theory can also guide analysis of how men participate and perceive women’s empowerment activities [21] and provide insight into programmatic implications by considering men and women in their social structures [26].

A recently completed trial to reduce IPV in rural Côte d’Ivoire offered a unique opportunity to examine perspectives of male partners in relation to women’s empowerment strategies in conflict-affected settings [17]. The need for such data has been underscored by calls to engage men and boys in the prevention of violence against women and as partners in promoting women’s rights [5, 27, 28]. The objective of the overarching trial was to evaluate the incremental effectiveness of combined social and economic programming on reductions in IPV, improvement in economic independence, household decision making and equitable gender attitudes, compared with economic programming only [17]. The trial yielded reductions in IPV and improvement in gender equitable norms, with statistically significant reductions in physical IPV among the most adherent couples [17]. The specific objectives of this current analysis were to provide qualitative understanding of men’s perceptions of gender norms, poverty and armed conflict, as they related to achieving programmatic goals, and to understand male partners’ participation in women’s empowerment programming in rural Côte d’Ivoire. The research questions were how men’s social identities manifest in this environment, what men’s attitudes were towards economic empowerment programming, why men participated and what benefits they saw from the program.

Methods

The current investigation focuses on qualitative data that were collected as part of a two-armed randomized controlled trial conducted in rural Côte d’Ivoire between 2010 and 2012: Reduction of Gender-based Violence against Women in Côte d’Ivoire. Both treatment and control arms received the economic programming component, which consisted of groups of women organized into village savings and loans associations (VSLAs). In addition to women’s participation in VSLAs, the treatment arm also received gender dialogue groups (GDGs), in which women and their male partners or male family members were invited to participate in an eight-session educational program. Although sessions focused on household financial well being, themes of gender equality, women’s contributions to the household and non-violence underscored all sessions. The GDGs, which included supportive discussions and activities, were based on the transtheoretical theory [29] to reduce IPV and improve financial decision making within households. Originally developed by the International Rescue Committee (IRC), groups were facilitated by two field staff (one male and one female staff who were trained in either gender-based violence or economic recovery). Example sessions on financial literacy included discussions on goal setting, modeling positive communication methods between men and women and activities to distinguish needs and wants.

This trial was conducted within 24 villages in rural, conflict-affected areas of Côte d’Ivoire. The evaluation was led by the Yale School of Public Health, in partnership with Innovations for Poverty Action and IRC. Further study details are described elsewhere [17].

The IRC field staff introduced the study to villages and asked eligible women (over 18 years, no previous experience with microfinance) to participate. During endline data collection that occurred between July and August 2012, qualitative indepth interviews were conducted among a subsample of female study participants and male partners to understand their experiences with the intervention. Villages where interviews took place were selected based on their high exposure to violence during the crisis in Côte d’Ivoire. For the subsample, maximum variation sampling of women participating in the intervention was employed in order to have a range of ethnicities. Male partners were then selected to participate based on the selection of their female partners from VSLA administrative records. To preserve confidentiality and minimize safety concerns, men and women were interviewed in separate villages and were not from the same couple. Overall, a total of 32 male partners were invited to participate. Three men declined participation due to prior obligations that would not allow them to be in the village during the scheduled interview. One woman’s husband had fled the village and thus was not available for the interview. These four men were replaced by selecting the partners of four additional women participating in the study, based on the same criteria described above. Interviews with women were of insufficient quality for analysis and thus, only men’s interviews are included in the current analysis.

All interviews, lasting no longer than 1.5 h, were conducted in a private location by trained male research assistants. Interviewers were language matched to participants; the majority of interviews were conducted in French eight were conducted in local languages (four were in Yacouba, three were in Guere and one in Dioula). Research assistants obtained verbal consent from participants, given concerns of low literacy. Audio-recording devices were used during the interview and participants were provided a list of health resources at the end of the interview. All study protocols were approved by the Yale School of Public Health and Innovations for Poverty Action institutional review boards.

Interview guides began with general issues regarding gender roles, such as roles of men and women in the household and in the village, challenges and advantages for men and women, consequences of not fulfilling responsibilities, and perceptions of IPV in their communities. For example, specific questions included, ‘What are your responsibilities in the household?’ and ‘What happens when a man does not fulfill his responsibilities in the house?’ Issues specific to the intervention centered on rationale for joining the groups, perceived benefits for women and their partners after participation, changes in relationship dynamics during the study period and identification of potential mechanisms through which perceived changes occurred, such as ‘What has changed with you and your partner since starting the group? What role do you think the group had in these changes?’ Only men in the treatment arm were asked the latter questions.

French-language interviews were transcribed and translated into English by outside bilingual French/English interpreters and were subsequently reviewed by Ivorian research staff for consistency and meaning. The eight interviews that occurred in the local languages were transcribed and translated into French by research staff and then translated into English by the outside interpreters. Coding structures were developed a priori by two research assistants and the principal investigator based on research questions focusing on process evaluation. These questions focused on the goals of the overarching study as well as process evaluation questions pertaining to the VLSA + GDG arm. Codes were also revised as themes emerged based on discussions with the research team through an inductive analytic approach [30]. All analyses were conducted in NVivo 10 [31].

Results

Findings are divided into four key themes that emerged from the data drawn from 32 interviewees related to the current investigation’s research questions: (i) intersections of masculinity, economic stress and exposure to armed conflict, (ii) attitudes towards economic empowerment programming, (iii) motivations for participating in programming and (iv) perceived benefits of GDGs.

Theme 1: intersections of masculinity, economic stress and exposure to armed conflict

Nearly, all men described traditional gender roles in their household and villages, such as men economically providing for the family or being in charge of decisions within households or village meetings. Men were described as typically engaging in income generating activities such as working in the fields or managing a small business with minimal direct family caretaking responsibilities. A usual day for women included managing the household, cooking and cleaning. However, a few men did discuss that some women have the dual burden of income generation and household responsibilities and must take on additional responsibilities, above and beyond those of men. For instance, one male reported:

“It is true that when you are born a woman you suffer. Today, when men finish their work, the women are the ones who keep on working. They are under the rain, they weed; And sometimes when they come back home they are tired; They go home and they start cooking; They sometimes tell us: “you men have nothing to do; we are now at an important moment, we are in a difficult period, we weed; we get tired and when we go back home, we must go in the kitchen to cook”. For these reasons we can say that the women also have a great responsibility.” (VSLA + GDG)

Men also described the challenges of being a man in rural Côte d’Ivoire, which largely centered on the lack of financial means to provide for their family’s food, school fees for children or clothing. Many men also described the ability to financially provide for their family as an integral component of their definition of manhood and being a respected man in their household and village. For instance, one male stated:

“When you are in the village, it is necessary to work to have money. When you have money, you are happy. When you dońt have money, it means you are not a man.” (VSLA only)

Another male described:

“What I like in being a man is when you have means, you are highly regarded by your friends and even by your children; but as you do not have means, you are not respected by your children; you are weak and your wife and your children can’t do anything.” (VSLA only)

As exemplified above, economic prosperity appears to be a key definition of manhood and masculinity in this setting. However, as illustrated below, men also described the financial hardships that they endured during the recent election-related violence in Côte d’Ivoire. Financial stressors from the election-related violence ranged from an inability to replace household items due to property theft to uncertainty regarding restarting a business for fear of having to flee in the future. These stressors directly created an environment of financial insecurity and inability to save for the future. As one man stated:

“Personally, I got many problems; I lost many things. Those who are here know that. I was completely broke because of the crisis. I had two shops, some properties, some mills. All of them were destroyed in the crisis. It happened that there was no understanding between my wife and me because there was nothing for food. Every day, she was in the habit of getting some kitchen money from me; it is what I have told you right now …” (VSLA + GDG)

This climate of financial insecurity and property theft due to widespread violence and displacement often created additional stressors within men’s relationships with their intimate partners as described by men. Guided by intersectionality theory, these economic stressors may have negatively impacted their perceived ability to fulfill their role as a man in their family. Other men also noted that in addition to financial insecurity, election-related violence also inflated prices for household purchases which created additional financial strains on families:

“It is money that is at the basis of all that we do. When you do not have money you cannot live. The crisis had bad impacts on us, the farmers in the village. We lack money. We do not know how to get dressed. The medical care is expensive. You cannot go to the hospital if you do not have money … If you do not have money you die. It was like that during the crisis. The crisis made everything expensive.” (VSLA + GDG)

Other men also noted that even if they did have a reasonable amount of money, the instability and violence made it difficult for men to begin new economic ventures, for fear of renewed armed conflict. For instance, one man stated:

“If peace is there and you have 25 CFA [Central African Franc] you can do a lot of things with it. But if there is no peace, you are not safe and each night you are scared because you are asking yourself if things won’t start again. If you start to undertake something, you will leave it and run away. This has scared everyone and I don’t want it to start again.” (VSLA + GDG)

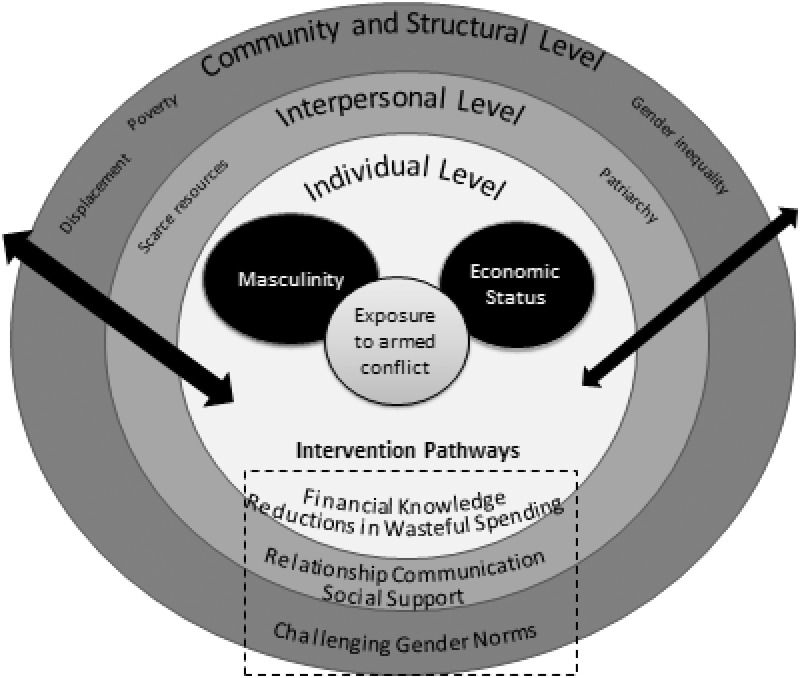

Taken together, the perspectives gleaned from men suggested how traditional male gender norms, which are rooted in men’s role as economic providers of the family, may be threatened during periods of armed conflict. These concerns may be particularly salient for men at the lowest rungs of socioeconomic status in an already impoverished context. Figure 1 shows a conceptual model adapted from Logie et al. [32], which illustrates the interactions of these social identities at the individual level within a larger multilevel framework of IPV perpetration in settings impacted by armed conflict [23].

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model of the intersections of men’s social identities and intervention pathways to reduce intimate partner violence. (Adapted with permission from [32] and [23]) .

Men were asked by interviewers about their thoughts on the consequences of unfulfilled traditional gender roles for both men and the women in their respective villages. Responses from men indicated that consequences of not fulfilling such roles were different between the two genders. For instance, women were held accountable for not fulfilling their household responsibilities, which may also involve elders:

“If she does not work, you can tell her parents, your older brothers … They will therefore call the woman to speak to her and tell her that what she is doing is not good. They will give some pieces of advice so that she behaves well.” (VSLA only)

In some cases, men explicitly mentioned perpetration of IPV against their wives:

“Before, when she did something wrong, I beat her and she ran away to her older sisters …” (VSLA + GDG)

When men did not fulfill their responsibilities, they discussed feeling a loss of respect in the community. Unlike the consequences faced by women, as described the male interviewees, the impacts were largely felt by his family as opposed to the man himself. As exemplified below, many men described the impact of a husband’s inability to financially provide for his family and the consequences they may suffer as a result. For example:

“… when the husband does not play his part, there is a lack at home; the children can’t do anything and there will be hunger. When you have no means to meet your needs, and if your wife is equally inactive, there will obviously be a food shortage at home. When she is penniless, the husband is solely responsible for every charge. I think this may cause the children to be involved in robbery.” (VSLA + GDG)

The above quote reveals the profound perceived effects a man’s inability to provide economically for his family may have on children’s health and well being. Additionally, while women were punished by men directly for not fulfilling their responsibilities, men were not equally punished nor held accountable by women in terms of violence. As seen in the preceding dimensions in this article, men may have difficulty financially providing for their family, a key gender role in this setting, during times of armed conflict. Reliance on such traditional gender norms may in turn create additional challenges for families, which may include increased food insecurity and IPV. As illustrated by the arrows in the conceptual model, men’s individual identities and experiences may be shaped by multiple interpersonal, community and structural levels. Specific characteristics of these levels included scarce resources and gender inequality. Taken together, these factors may exacerbate levels of IPV in times of conflict or instability.

Theme 2: attitudes towards economic empowerment programming

After discussion of gender norms, poverty and armed conflict in villages, interviews shifted to focus on men’s perceptions of women’s economic empowerment programming. Men were first asked about their thoughts on their female partners’ participation in such programming.

Perceptions of VSLA programs were generally favorable, particularly among men who also participated in the GDGs, as they were pleased their wives had increased income. However, a small number of men expressed concerns, such as perceiving VSLAs and GDGs to be primarily for women’s rights, without having direct benefits for the men and increased mobility of women that is required for attending meetings of group-based economic programming. For instance, one man stated:

“The negative aspect … is that they hold their meeting up to midnight whereas they are all married women with all that it implies. We accepted that our wives join but still it is necessary to change.” (VSLA only)

Nonetheless, while some men had mixed perceptions of their female partners participating in the VSLAs, most men had positive views.

Theme 3: motivations for participating in programming

After discussion of VSLAs, the male partners who participated in the gender transformative component of the intervention, GDGs, were asked additional questions. Of the 32 total male interviewees, 14 men participated in the GDG programming along with their female partners. The following only uses data drawn from these 14 men.

Given the tenuous climate in rural Côte d’Ivoire of vacillating peace and instability and widespread poverty, it was not surprising that men were eager to learn financial skills through participation in the GDGs. In addition, while financial motivation was what drew men to initially join the program, and was used as a ‘selling point’ by program staff, men articulated multiple reasons for participation, as illustrated below:

“What drove me to join the group, it is like a school. What also drove me, it is that we learned how to live with your wife in the house in order not to have of argument, how to save our goods, how to raise our children so that they can succeed. There are several things like that which encouraged me to join the group.”

Men’s financial motivations for participation in the GDGs may be linked for their desire to be respected in their villages. Again, the definition of manhood in this context is paramount, whereas money, financial prosperity and respect from others are inextricably linked. Additionally, many men described a desire to learn information about how to be a better husband and father, above and beyond learning about financial planning and budgeting. For instance, one man stated:

“What prompted me to take part in this group is the advice that people give; how to manage and have a happy family; how to manage to take care of the family. It is all that I like and which prompted me to join.”

Theme 4: perceived benefits of participation

After dialoguing about their motivations for participation in the gender transformative component of the program, men were asked about their perceived benefits. Subthemes regarding the perceived benefits of the combined social and economic empowerment approach centered on: (i) financial decision making (individual level), (ii) improved relationships within couples and social support among men in the village (interpersonal level) and (iii) challenging inequitable gender norms (community level) and are illustrated in Fig. 1 in the intervention pathway box.

Individual level: financial decision making and reductions in wasteful spending

Almost all men in the VSLA + GDG group described changes in couple negotiations around spending and saving money in their household, which had the potential to result in benefits for men, women and children. For instance, men started making financial decisions jointly with their wives based on the needs of the household:

“Before, when I had money, I spent it alone. But from now on, when I have money, I do not spend it alone anymore; I present it to my wife so that we make expenditure for the family.”

Another man described increased communication between his wife and himself, including transparency of household finances:

“Before each had his/her money; when I earned money, I spent it without her say; and what remained I kept it. But now, we do everything together; and what remains like money with me I show her that. That has changed me a lot! We should not hide what we have to our wife or our husband. It is like that.”

These findings are mirrored in the quantitative analyses which demonstrated that women who participated in the VSLA and the GDGs with their male partner reported a 61% reduction in economic abuse compared with women randomized to VSLA only [17]. In addition to increased communication and joint decision making, a salient-related dimension was the reduction of wasteful spending, particularly on alcohol. For instance, one man stated:

“There was a change of lifestyle. We wasted what we earned. I am a smoker and I am an alcohol drinker. But now, I have changed a little; I even changed a lot. I stopped, it is difficult to give that up, it is gradually that I will be able to completely stop that. It is thus the change which has come.”

Other men also described increased savings as a result of decreasing wasteful spending. In sum, while traditional gender norms suggest men be seen as the primary provider and decision maker in these rural villages, participation in the GDGs may have aided some transformation regarding household norms for financial spending.

Interpersonal level: improved relationships within couples

Many men also described reduced arguments in the household around financial issues and general improvements in communication and non-violent approaches to solving conflict. In addition, the majority of men also reported increased respect for their wives and women’s ability to financially contribute to the household as well as increased recognition of their non-monetary contributions to the household.

“Since we are in the group, there are no longer arguments … Before, when there was argument, each one made his/her things individually. There is a great difference; there is no more individuality; one makes all the things together. When we want to do work, we decide of which work to do, and when we earn money from the work, we decide on what we are going to do with the money. When it’s like that, there is no quarrel, there is no argument in the household.”

In addition to increased communication among couples, men also described changes in anger and the use of violence against their wife and children, as illustrated below:

“The change that I like the most is the fact that I left my anger. I saw that violence is not important. Violence towards my wife and children is not worthwhile. Between the man and the woman, there will always be something which will annoy one of them. This will always happen. But I think that now I know how to control myself, I can now control myself and avoid that behavior in my life because of the training I have had.”

In some instances, increased communication led to reductions in emotional abuse as described below:

“The change that I like very much is the fact that between my wife and me everything is alright, there are no more violent words, and there are no more exits without the permission of the man, exits without having the woman aware. When we want to go out, we go together; when we want to do something, we sit down and we discuss. I believe that it is this change that I noticed.”

Overall, men seemed to discuss improved relationships with their partners and children which they attributed to their participation in the GDGs. Although the intent-to-treat quantitative evaluation of the program did not reveal statistically significant reductions in IPV, women who attended at least six of eight GDG sessions with the male partner reported a relative decrease in physical IPV by 55%, compared with women who were in the VSLA only group [17].

Increased social support with other men in community

A common benefit described by male participants was social support they had received from other men in the discussion groups. The majority of these men described how other males provided advice and guidance regarding behaviors in the household and not limited to only the discussion group sessions. A few men also described how they would help settle problems in other households of men who did not participate in the groups:

“We continue after the training sessions to interact and give advice to each other. We are informed each day about how others are doing. How is his family doing? If there is something that is not doing well, we take one day and give him advice. Therefore, we live like brothers.”

However, one participant noted that because males were not engaged in the economic component of VLSAs, there was limited social cohesion among men in the GDGs:

“… But I have no personal relationship with the men who attend the group too. It is at least women … Because they said the training was only for women. We men, we participate in it freely. We have not even got any ideas to initiate things the way the women did. So, there is no sincerity among us. It was difficult to the women. We, men, took part in it as their husbands. We, men, did not get any personal relationship with the training. There was none!”

Although not a common criticism of the program, it appeared that some men may be jealous of women who participate in economic empowerment programs, such as VSLAs. Again, this criticism may in large part be due to pervasive inequitable gender norms and instability threatening livelihoods in this context.

Community level: challenging inequitable gender norms

Men were also asked about their general perceptions of the GDGs and if they would recommend them to other men in the community. Understanding acceptability and men’s propensity to challenge inequitable gender norms in their communities is critical to assessing the potential for replicability and sustainability of the program. Most men‘s interviews indicated that these groups were acceptable as they described being generally pleased with the programming. Acceptability was also shown through attendance: nearly half of men attended at least six of eight GDG sessions along with their female partner. Once the program was completed, they actively spread information to other men in the community who did not participate in the study. For instance:

“When we completed the training I went to see a brother … I went to tell him we have been trained, this training has really changed our way of living in the home. The training is over, but we will not stop. We who have been trained, we cannot stop; I will also train you. I will give you the information I received because it is very important.”

Overall, it appeared that men found the groups acceptable and were overwhelmingly supportive of this program’s approach to women’s social and economic empowerment programming.

Discussion

In this rural Ivorian context, findings document the profound interlinking of traditional gender norms, poverty and armed conflict and their impacts on a household’s well being. Violence against women may be intensified due to these synergistic factors in the aftermath of conflict, in which different social identities interact across multiple levels to perpetuate IPV [23]. In particular, interviews highlighted a strong reliance on traditional gender norms in which men were the economic providers of the family, a common norm in other settings [28, 33]. Therefore, their perceptions of their own masculinity may have been threatened in times of armed conflict, primarily due to property theft and an inability to start future business opportunities. This, in turn, may catalyse instances of IPV in households where men may use violence to reassert their power. Similar findings have been documented in East Africa, in which men compensate for their reduced sense of masculinity through increased numbers of sexual partnerships and sexual control over women [34], as well as among resettled refugees in Australia, in which men’s loss of ‘breadwinning’ status was identified as a precipitating factor in IPV perpetration [35]. In addition, other studies have also documented additional factors, including exposure to political violence, which have been implicated in escalated odds of perpetrating IPV among other populations [36–38]. The complex interplay of instability, masculinity, trauma experiences and poverty suggest that intersectionality may be a useful framework in conflict-affected environments to understand men’s experiences as they relate to perpetration of IPV. Quantitative evaluations with men should seek to understand causal pathways between armed conflict experiences, masculinity and IPV perpetration.

Programmatically, findings suggest that incorporation of men into women’s social and economic programming may be a feasible approach to address IPV in this conflict-affected setting, as downward trends of physical and/or sexual IPV and economic abuse that were documented in the quantitative evaluation when economic empowerment programming of women was combined with a gender transformative approach [17]. In particular, recruitment of men through learning opportunities to manage finances seemed particularly appealing, and thus served as a platform to introduce discussions around larger gender norms and IPV. Recruiting men into gender transformative programming, based on the prospect of gaining financial literacy may be particularly advantageous, given the economic challenges both men and women face in conflict-affected settings, as well as other impoverished areas. Mechanisms of change, which may operate at multiple levels, presented within the qualitative findings, may have included increased communication and joint decision making around finances, which are particularly salient in regards to the observed reductions in economic abuse. Future women’s empowerment interventions should qualitatively and quantitatively measure these potential pathways and women’s access to resources and decision making around the use of resources [39, 40].

Recent research from the Democratic Republic of Congo suggests that engaging men and understanding their perspectives may be important in the post-conflict period as a long-term strategy to improve gender equity [28]. Current findings bolster this recommendation for future programming efforts in conflict-affected settings. Nonetheless, it is imperative that men only or combined couple-level interventions that seek to reduce gender-based violence against women do not validate masculinities that serve to threaten the well being of women [41]. For instance, careful facilitation should be implemented in order to avoid the domination of discussions by men over women in couple-level interventions. Furthermore, program experience suggests that activities should only be implemented with direct feedback and guidance from women in the community [42]. As women experience an additional level of oppression based on their lower social status in comparison to men, ensuring that the building of women’s agency while engaging men should remain at the forefront of programmatic priorities. In the current trial, this was accomplished by underscoring the important contributions women made to household well being and non-violence in all GDG sessions that centered on household finances.

There are several considerations when interpreting the results of the current study. Primarily, the respondents were not randomly chosen for interviews as they were selected in areas that were highly affected by recent election-related violence. Therefore, we have a uniquely vulnerable sample of men, and the relationships of poverty, conflict and gender norms, may not reflect the diversity of experiences of men during this tumultuous period in Côte d’Ivoire. In addition, the men are partners of women who were participating in a randomized controlled trial and may be different from other men whose female partners chose not to or were not allowed to participate in the overarching study. We were also unable to quantitatively assess men’s reports of perpetration of violence and compared them to the women’s experiences of victimization, nor were women’s qualitative interviews included in the present analyses. These comparisons would illuminate possible reporting differences and highlight potential social desirability bias in the qualitative interviews.

Despite these limitations, the analyses offer important insights regarding men’s experiences and engagement with programming for women’s empowerment. In this context, men demonstrated potential to be active partners in empowering their female partners through economic programming, which could have far-reaching effects on households’ well being. Considerations of inequitable gender norms and its intersections with economic status, conflict and wider instability must be considered in humanitarian programming seeking to reduce IPV in the aftermath of conflict. Understanding and addressing these structural determinants of IPV may have the potential to promote resilience in women, couples and families in these unstable contexts.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants of the study and the research assistants who carried out the study.

Funding

This work was supported by the World Bank’s State and Peace-building Fund, Contracts (1007007040 and 7162336) (principal investigator J.G). This work was supported, in part, by Yale University’s Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS (CIRA), through grants from the National Institute of Mental Health, Paul Cleary, PhD, principal investigator (P30MH062294). The views presented are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the World Bank, NIMH, NIH or IRC. Study sponsors had no role in the planning of the study or in writing/approving the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1.Fulu E, Jewkes R, Roselli T, et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with male perpetration of intimate partner violence: findings from the UN Multi-country Cross-sectional Study on Men and Violence in Asia and the Pacific. Lancet Global Health. 2013;1:e187–207. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Global and Regional Estimates of Violence Against Women: Prevalence and Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-Partner Sexual Violence. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, South African Medical Research Council. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heise L, Ellsberg M, Gottmoeller M. A global overivew of gender-based violence. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;78:S5–14. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(02)00038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellsberg M, Jansen HAFM, Heise L, et al. Intimate partner violence and women’s physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence: an observational study. Lancet. 2008;371:1165–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60522-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barker G, Ricardo C, Nascimento M. Engaging Men and Boys in Changing Gender-Based Inequity in Health: Evidence from Programme Interventions. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunkle KL, Jewkes R. Effective HIV prevention requires gender-transformative work with men. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83:173–4. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.024950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Addressing Violence Against Women and Achieving the Millennium Development Goals. Geneva: WHO; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barker G, Contreras JM, Heilman B, et al. Evolving Men: Initial Results from the International Men and Gender Equality Survey (IMAGES) Washington, DC and Rio de Janeiro: International Center for Research on Women and Instituto Promundo; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordon DM, Hawes SW, Reid AE, et al. The many faces of manhood: examining masculine norms and health behaviors of young fathers across race. Am J Mens Health. 2013;7:394–401. doi: 10.1177/1557988313476540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowleg L, Teti M, Malebranche DJ, et al. “It’s an uphill battle everyday”: intersectionality, low-income black heterosexual men, and implications for HIV prevention research and interventions. Psychol Men Masc. 2013;14:25–34. doi: 10.1037/a0028392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shai NJ, Jewkes R, Nduna M, et al. Masculinities and condom use patterns among young rural South African men: a cross-sectional baseline survey. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:462. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Courtenay WH. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: a theory of gender and health. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:1385–401. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00390-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Decker MR, Seage GR, III, Hemenway D, et al. Intimate partner violence perpetration, standard and gendered STI/HIV risk behaviour, and STI/HIV diagnosis among a clinic-based sample of men. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85:555–60. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.036368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woodall JR, Warwick-Booth L, Cross R. Has empowerment lost its power? Health Educ Res. 2012;27:742–5. doi: 10.1093/her/cys064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wallerstein N. Powerlessness, empowerment, and health: implications for health promotion programs. Am J Health Promot. 1992;6:197–205. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-6.3.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pronyk PM, Hargreaves JR, Kim JC, et al. Effect of a structural intervention for the prevention of intimate-partner violence and HIV in rural South Africa: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2006;368:1973–83. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69744-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta J, Falb KL, Lehmann H, et al. Gender norms and economic empowerment intervention to reduce intimate partner violence against women in rural Côte d’Ivoire: a randomized controlled pilot study. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2013;13:46. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-13-46. doi:10.1186/1472-698X-13-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim J, Pronyk P, Barnett T, et al. Exploring the role of economic empowerment in HIV prevention. AIDS (London, England) 2008;22(Suppl. 4):S57–71. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000341777.78876.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vyas S, Watts C. How does economic empowerment affect women’s risk of intimate partner violence in low and middle income countries? A systematic review of published evidence. J Int Develop. 2009;21:577–602. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schuler SR, Hashemi SM, Riley AP, et al. Credit programs, patriarchy, and men's violence against women in rural Bangladesh. Soc Sci Med. 1996;43:1729–42. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dworkin SL, Dunbar MS, Krishnan S, et al. Uncovering tensions and capitalizing on synergies in HIV/AIDS and antiviolence programs. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:995–1003. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.191106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garikipati S. The impact of lending to women on household vulnerability and women's empowerment: evidence from India. World Develop. 2008;36:2620–42. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Annan J, Brier M. The risk of return: intimate partner violence in Northern Uganda’s armed conflict. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:152–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowleg L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: intersectionality- an important theoretical framework for public health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1267–73. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cole ER. Intersectionality and research in psychology. Am Psychol. 2009;64:170–80. doi: 10.1037/a0014564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dworkin SL. Who is epidemiologically fathomable in the HIV/AIDS epidemic? gender, sexuality, and intersectionality in public health. Cult Health Sex. 2005;7:615–23. doi: 10.1080/13691050500100385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.International Center for Research on Women. Engaging Men and Boys to Achieve Gender Equality: How Can We Build on What We Have Learned? Washington, DC: International Center for Research on Women; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slegh H, Barker G, Ruratotoye B, et al. Gender Relations, Sexual Violence and the Effects of Conflict on Women and Men in North Kivu, Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo: preliminary results from the International Men and Gender Equality Survey (IMAGES) Cape Town, South Africa and Washington, DC: Sonke Gender Justice Network and Promundo-US; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12:38–48. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. 2006;27:237–46. [Google Scholar]

- 31. NVivo qualitative data analysis software, version 10: QSR International Pty Ltd, 2012.

- 32.Logie CH, James L, Tharao W, et al. HIV, gender, race, sexual orientation and sex work: a qualitative study of intersectional stigma experienced by HIV-positive women in Ontario, Canada. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jewkes R, Morrell R, Sikweyiya Y, et al. Men, prostitution, and the provider role: understanding the intersections of economic exchange, sex, crime, and violence in South Africa. Plos One. 2012;7:e40821. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silberschmidt M. Disempowerment of men in rural and urban East Africa: implications for male identity and sexual behavior. World Develop. 2001;29:657–71. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fisher C. Changed and changing gender and family roles and domestic violence in African refugee background communities post-settlement in Perth, Australia. Violence against Women. 2013;19:833–47. doi: 10.1177/1077801213497535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta J, Acevedo-Garcia D, Hemenway D, et al. Premigration exposure to political violence and perpetration of intimate partner violence among immigrant men in Boston. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:462–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.120634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clark CJ, Everson-Rose SA, Suglia SF, et al. Association between exposure to political violence and intimate-partner violence in the occupied Palestinian territory: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2010;375:310–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61827-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jewkes R. Intimate partner violence: causes and prevention. Lancet. 2002;359:1423–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08357-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kabeer N. Resources, agency, achievements: reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Develop Change. 1999;30:435–64. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goetz AM, Gupta RS. Who takes the credit? gender, power, and control over loan use in rural credit programs in Bangladesh. World Develop. 1996;24:45–63. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gibbs A, Willan S, Misselhorn A, et al. Combined structural interventions for gender equality and livelihood security: a critical review of the evidence from southern and eastern Africa and the implications for young people. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15(Suppl. 1):1–10. doi: 10.7448/IAS.15.3.17362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.International Rescue Committee. Part 1: Introductory Guide. Preventing violence against women and girls: Engaging Men Through Accountable Practice. New York: International Rescue Committee; 2013. [Google Scholar]