Abstract

Background

Depression collaborative care implementation using community engagement and planning (CEP) across programs compared to technical assistance to individual programs (Resources for Services, RS) in minority communities improves 6-month client outcomes. However, 12-month outcomes are unknown.

Objective

To compare effects of CEP and RS collaborative care implementation interventions on depressed clients’ mental health-related quality of life (MHRQL) and services use at 12-months.

Design

Matched health and community programs (n=93) in two communities randomized to CEP or RS.

Measurements

Self-reported client MHRQL, and services use at baseline, 6, and 12-months.

Setting

Los Angeles.

Patients

Adults (n=1018) with depressive symptoms (8-item Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ-8]≥10); 85% ethnic minority.

Interventions

CEP and RS to implement depression collaborative care.

Measurements

Primary outcome: Poor MHRQL (12-item Mental Composite Score [MCS-12]≤40) at baseline, 6, and 12-months; Secondary outcomes: 12-months services use.

Results

At 6-months, the finding that CEP outperformed RS to reduce poor MHRQL was significant, but sensitive to underlying statistical assumptions. Similarly, at 12-months, some analyses suggested that CEP was advantageous on MHRQL, while other analyses did not confirm a significant difference favoring CEP. The finding that CEP reduced behavioral health hospitalizations at 6-months was not clear at 12-months with findings sensitive to underlying statistical assumptions. Other services use was not significantly different between interventions at 12-months.

Limitations

Self-reported data. Findings are sensitive to modeling assumptions.

Conclusions

In contrast to 6-month results, our findings did not show consistent CEP effects on reducing the likelihood of poor client MHRQL and behavioral health hospitalizations at 12-months. Still given under-resourced communities’ needs, CEP's favorable profile, and the absence of evidence-based alternatives, community engagement remains a viable strategy for policymakers and community to consider.

INTRODUCTION

Depression and depressive symptoms are main causes of disability in the United States (1,2), where racial disparities persist in access, quality and outcomes of care (3-9). Depression collaborative care provided in primary care settings can improve quality and outcomes of care for depressed adults while reducing racial outcome disparities (10-18), but safety-net primary care settings generally have limited capacity for full implementation of collaborative care (19-21). Encouraging safety-net clinics to collaborate with other key agencies (i.e. social services, faith-based) using community engagement (22-26) may support successful depression collaborative care implementation across under-resourced communities.

Community Partners in Care (CPIC) was designed to compare the effects of two depression collaborative care implementation approaches: 1) community engagement and planning (CEP) supporting collaborative planning and implementation across myriad community programs; and 2) more traditional resources for services (RS) relying on time-limited expert technical assistance for collaborative care to individual programs (27-29). Earlier studies concluded that at 6-months, relative to RS, CEP reduced depressed clients’ probability of poor mental health-related quality of life, increased their physical activity, and reduced risk factors for homelessness (28-30). Moreover, CEP reduced behavioral health hospitalizations and specialty medication visits among visitors to mental health specialists, while increasing primary care, faith-based, and park-based services for depression among such users. To our knowledge, CPIC is the first randomized U.S. study of the added value of community engagement and planning beyond more traditional expert assistance to individual programs and the first depression collaborative care study to span healthcare and social-community sectors.

For this study, we examined the effects of CEP over RS on poor mental health-related quality of life (MHRQL) and services use at 6 and 12-months, as well as the changes in outcomes from baseline to 6-months and baseline to 12-months. We hypothesized that CEP relative to RS would decrease the proportion of clients with poor MHRQL at 12-months.

METHODS

Design Overview

Community Partners in Care is a group-level randomized comparative effectiveness trial comparing CEP to RS. Both intervention conditions were designed to provide extensive depression collaborative care trainings to mental health, medical, and community-based agencies. RS provided preset, time-limited trainings to individual agencies while CEP encouraged these myriad agencies to develop a strategy and training plan to jointly provide care for depression (Table 1). The interventions and study methods have been described previously (28-31).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Depressed Clients (N=1,018) in Outcomes Analysis, by Intervention Condition*

| Characteristics | Overall (N=1018) | RS (N=504) | CEP (N=514) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Service sector, no. (%) | |||

| Primary care or public health | 290 (28.5) | 134 (26.6) | 156 (30.4) |

| Mental health services | 195 (19.2) | 110 (21.8) | 85 (16.5) |

| Substance abuse | 230 (22.6) | 111 (22.0) | 119 (23.2) |

| Homeless services | 162 (15.9) | 92 (18.3) | 70 (13.6) |

| Community-based | 141 (13.9) | 57 (11.3) | 84 (16.3) |

| Age, years | 44.8 ± 12.7 | 44.2 ± 12.3 | 45.3 ± 13.0 |

| Female, no. (%) | 595 (58.4) | 286 (56.7) | 309 (60.1) |

| Ethnicity, no. (%)† | |||

| Latino | 409 (40.2) | 194 (38.5) | 215 (41.8) |

| African American | 488 (47.9) | 239 (47.4) | 249 (48.4) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 86 (8.4) | 45 (8.9) | 41 (8.0) |

| Other | 35 (3.4) | 26 (5.2) | 9 (1.8) |

| Married or living with partner, no. (%) | 231 (22.7) | 116 (23.0) | 115 (22.5) |

| Less than high school education, no. (%) | 446 (43.8) | 221 (43.9) | 224 (43.7) |

| ≥3 chronic medical conditions of 18, no. (%) | 548 (53.8) | 270 (53.6) | 278 (54.0) |

| Family income from work, past 12 months≤$10,000, no. (%) | 755 (74.1) | 374 (74.2) | 381 (74.0) |

| Family income under federal poverty level, no. (%) | 750 (73.7) | 373 (74.0) | 377 (73.3) |

| No health insurance, no. (%) | 545 (53.5) | 286 (56.7) | 259 (50.4) |

| Working for pay, no. (%) | 205 (20.1) | 105 (20.9) | 100 (19.4) |

| 12-month depressive disorder, no. (%) | 629 (61.8) | 311 (61.8) | 318 (61.8) |

| Probable depression (PHQ-8≥10) | 992 (97.7) | 490 (97.4) | 502 (98.0) |

| PHQ-8 score, mean (SD) | 14.9 ± 4.1 | 15.0 ± 4.2 | 14.8 ± 4.1 |

| Alcohol abuse or use of illicit drugs 12 months, no. (%) | 398 (39.1) | 180 (35.8) | 218 (42.4) |

| Poor mental health-related quality of life, no. (%)‡ | 546 (53.6) | 271 (53.7) | 275 (53.5) |

Data are presented as No. (%) or mean (SD).

RS=Resources for Services or individual program technical assistance; CEP=Community Engagement and Planning; Plus–minus values are means ±SD; data were multiply imputed; Chi-square test was used for comparing two groups accounting for the design effect of the cluster randomization

P>0.30 for all comparisons except for ethnicity p=.03

MCS-12≤40; one standard deviation below population mean.

The study and CEP intervention were guided by Community-Partnered Participatory Research (CPPR) principles (32-35), a Community-Based Participatory Research variant (36,37), promoting equal authority among community and academic partners. The study council, co-led by UCLA, RAND, Healthy African American Families II, Behavioral Health Services, and QueensCare Health and Faith Partnership supported workgroups and community forums for study input (27-31,38,39).

Setting

The study took place in two Los Angeles County communities, South Los Angeles and Hollywood-Metro, with high rates of poverty, avoidable hospitalizations, and low rates of insurance (40-42). We hosted community meetings to identify for oversampling those community-based settings that support vulnerable depressed populations; these settings included mental health, primary care, public health, substance abuse, social services, faith-based programs, parks, senior centers, hair salons, and exercise clubs. South Los Angeles partners emphasized inclusion of large samples of substance abuse clients and African Americans, while Hollywood-Metro emphasized homeless clients and seniors.

Participants and Randomization

Programs

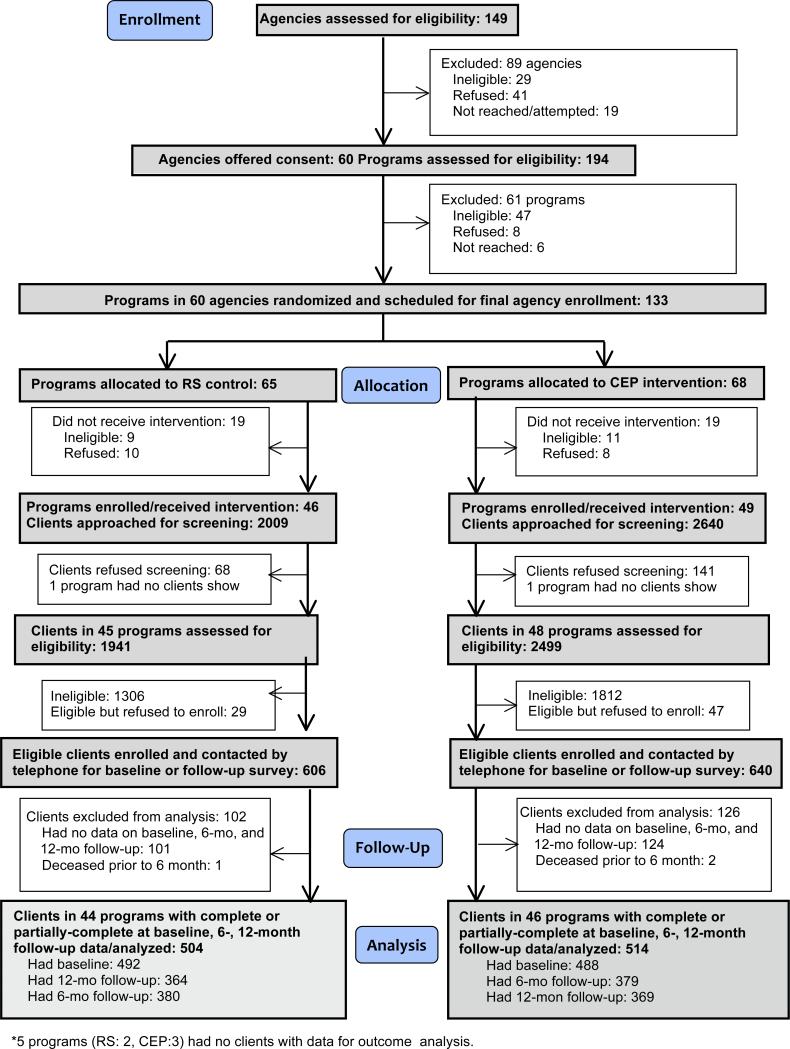

We began by identifying a pool of relevant agencies and organization through county program lists and nominations from community partners. We then contacted each to assess interest, eligibility, and enrollment. This process resulted in a pool of 60 potentially eligible agencies with 194 programs. Program eligibility criteria were serving ≥ 15 clients per week, having one or more staff, and not exclusively focused on psychotic disorders or home services. A total of 133 of these 194 programs were potentially eligible. Within each community, programs or clusters of smaller programs were paired based on geographic location, service sector, size, population served, services provided, and funding streams; two larger agencies were their own stratum. Within pairs, one program/ cluster was randomized to CEP and the other to RS (43). A statistician uninvolved with recruitment supported council members in producing seed numbers for randomization (44). Within 60 potentially eligible agencies with 194 programs, 133 programs were potentially eligible (serving ≥ 15 clients per week, one or more staff, not focused on psychotic disorders or home services) and randomized (65 RS, 68 CEP; Figure 1). Site visits post-randomization to finalize enrollment were conducted by RAND staff blinded to assignment: 20 programs were determined ineligible, 18 refused participation, and 95 programs from 50 consenting agencies were enrolled (46 RS, 49 CEP; Figure 1). Administrators were informed of intervention status by letter. Participating and nonparticipating programs were comparable in age, sex, race, population density, and income by zip code (each p>0.10) as determined by analysis of census tract data.

Figure 1.

Trial Profile

Clients

To achieve a 6-month follow-up sample of 780 depressed clients, we planned to enroll 557-600 clients per condition (assuming 65-70% retention). We powered the study to identify a detectable effect size ranging from 0.20–0.22 and a percentage point difference between groups ranging from 9.98–10.91%, assuming 80% power with alpha=0.05 (two-sided), with an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) assumed to range from 0.00–0.02 (43,45,46).

Within programs, clients were screened in waiting rooms (approached consecutively) or at events (approached randomly) from March to November 2010. RAND staff blinded to intervention status approached 4,649 adults (age ≥ 18) allocating 2–3 days per program, and 4,440 (95.5 %) agreed to screening. Eligibility was limited to clients providing contact information and having at least mild depressive symptoms, a score on the 8-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8)≥10 (47). Of 4,440 screened, 1,322 (29.8 %) were eligible, and of these 1,246 (94.3 %) enrolled, a high rate for such studies (11,14,16). Between April 2010 and January 2011, 981 clients (79% of enrolled) completed a baseline telephone survey conducted by RAND survey staff blinded to intervention condition. Of 1,093 participants approached for 6-month telephone follow-up surveys between November 2010 and August 2011, 759 (70%) participated. Of 974 participants approached for 12-month telephone follow-up surveys between May 2011 and March 2012, 733 (75%) participated. We did not attempt to contact 272 participants because their survey response at baseline (n=153) or 6 months (n=119) was final refusal, ill, incarcerated, unable to contact, or deceased. Our analytic sample is comprised of 1,018 individuals (77% of eligible, 82% of enrolled) who completed ≥1 survey across baseline, or 6-months, or 12-months (Figure 1). Characteristics of 12-month survey completers differed from non-completers by intervention. RS had significantly higher nonresponse rates among men, clients recruited from the substance abuse programs, and those with no health insurance. In CEP, responders were more likely to have lower family income and to be African American (Appendix B, Table B2-B4).

Interventions

Compared interventions, CEP and RS, were designed to expose a range of healthcare and social-community agencies to the same depression collaborative care toolkits. Between December 2009 and July 2011, CEP supported program administrators to work as councils: one in Hollywood-Metro and another in South Los Angeles. Each council met bi-weekly over 5 months to adapt depression care toolkits and trainings to each community. In addition, each council developed plans for a coordinated services network across healthcare and social-community programs to support depressed adults. Planning was co-led by community and academic council members following CPPR principles (e.g. shared authority and two-way knowledge exchange) (39). (Appendix Table 1)

RS offered technical assistance to assigned programs for the depression care toolkits using a “train-the-trainer” model. Between December 2009 and July 2010, trainings were conducted through ten webinars plus site visits to primary care for each community (39). Trainers included a nurse care manager, licensed psychologist cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) trainer, three board-certified psychiatrists for medication management, and community service administrators to support participation and cultural competence.

Toolkits

The CPIC Council modified depression collaborative care toolkits (48) supporting clinician assessment, medication management, case management (screening, care coordination, and patient education), patient education, and CBT (14,16,17,48,49); adding a lay health worker manual and team support tools (50,51). Toolkits introduced to programs prior to randomization at one-day kick-off conferences in each community were available online, through flash drives, and hardcopy (27,38,39), for participating programs in both interventions. (Appendix Table 1)

After randomization and enrollment, within each intervention condition, training invitations were offered by phone, e-mail, and postcards to staff attending prior CPIC study meetings with encouragement to circulate to all eligible staff. Providers and clients in enrolled programs could use intervention resources for free, even if not individually enrolled as participants. Training participation incentives included continuing education credits, trainings, and food during trainings. Enrolled client lists were provided to CEP, but not RS administrators, except one agency with a shared waiting room where both were given lists.

Institutional Review Boards (RAND and other participating agencies) approved study procedures before initiation. The National Institutes of Health did not consider the study a clinical trial when funded in 2007 and no data safety monitoring board was required. Post data collection; the study was registered (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01699789). No major design changes were made after recruitment began.

Outcomes and Follow-up

All outcomes were based on client self-report telephone surveys assessed at baseline, 6-, and 12-months by RAND staff. Baseline measures include program intervention assignment and sector; and client data from the screener and baseline survey on demographics (age, sex), presence of ≥3 chronic conditions from 18 conditions, education level, race/ethnicity; from the 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) (52,53) physical and mental health composite scores (PCS-12, MCS-12) and meeting federal family poverty criteria (54). Using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) (55), we assessed using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Psychiatric Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria: 12-month major depressive or dysthymic disorder, current manic episode, recent anxiety disorder (1-month panic or post-traumatic stress or 6-month generalized anxiety disorder), and 12-month alcohol abuse or use of illicit drugs.

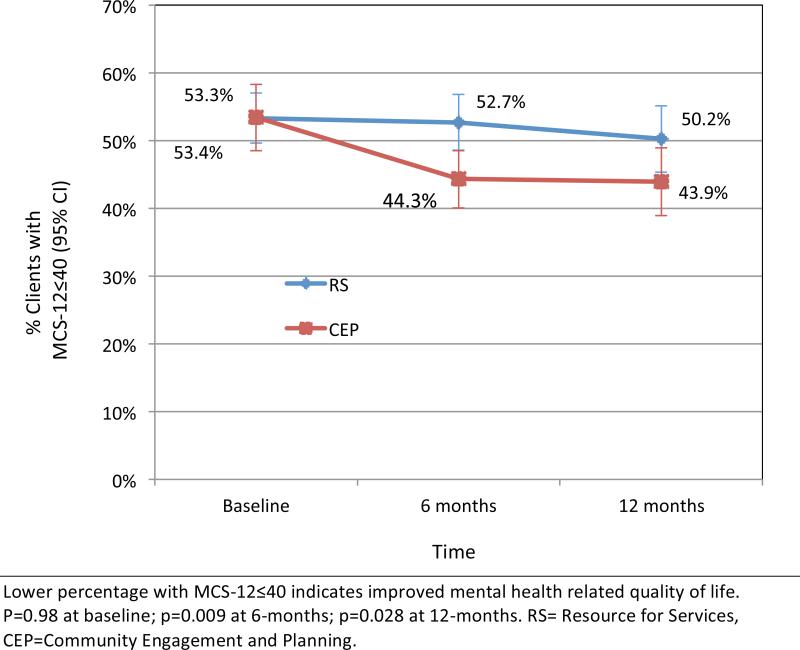

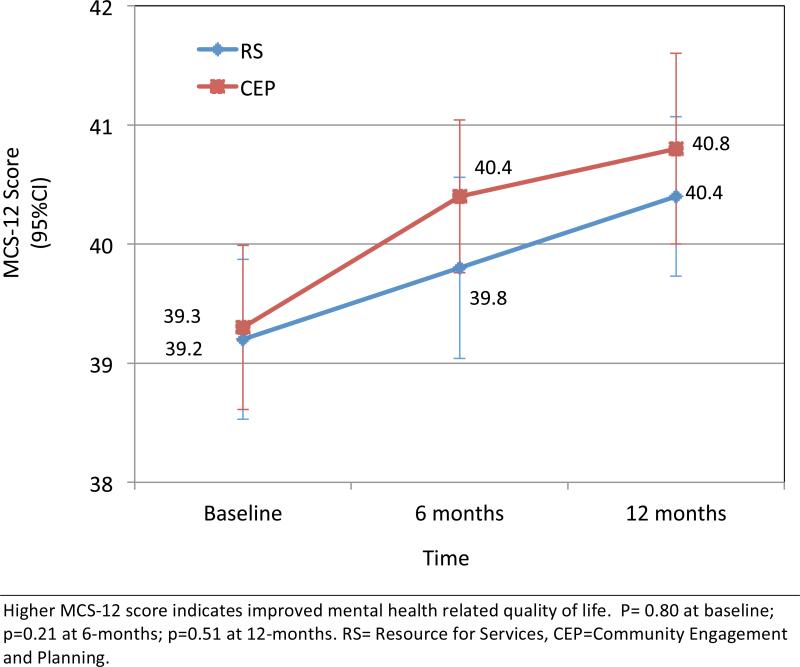

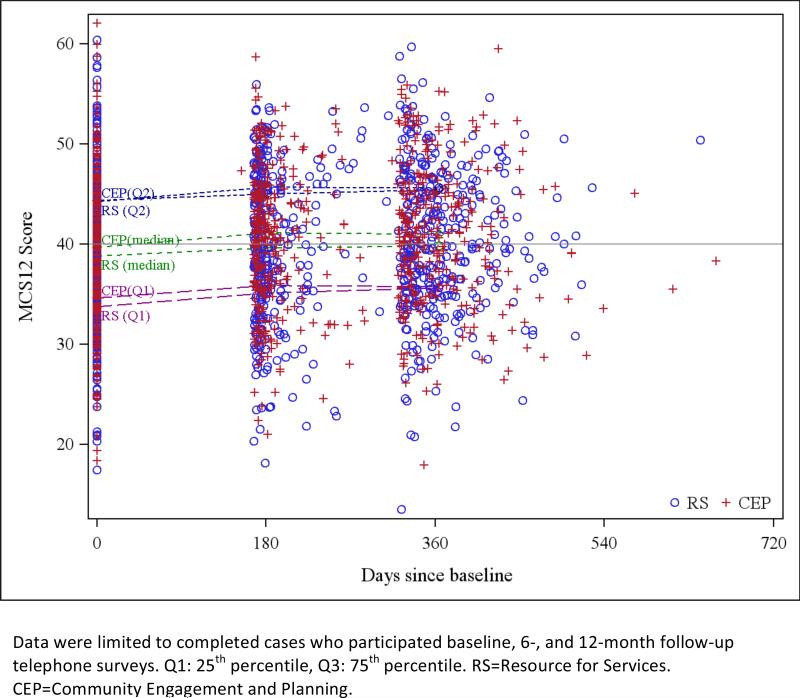

The primary study outcome was percentage of clients with poor mental health-related quality of life (MHRQL), i.e. 12-item Short Form Health Survey mental component score (MCS-12)≤40, one standard deviation below U.S. population mean, at 12-months (52,53). A sensitivity analysis was conducted with the MCS-12 as a continuous measure. Secondary outcomes were services use indicators (e.g. primary care visits, behavioral health hospital nights). We report 6- and 12-month outcomes, and the change in outcomes from baseline to 6- and 12-months. For all outcomes, we also report sensitivity analyses results with survey follow-up time as a class variable and varying imputed data assumptions.

We assessed services use in the past 6 months for behavioral health (mental health, alcohol, substance abuse). In particular, we asked clients about the number of nights spent in a hospital, overnight substance abuse rehabilitation, emergency room (ER) visits, outpatient mental health or self/family groups visits, hotline calls, and use of outpatient primary care or public health clinics, substance abuse or social services programs, parks and community centers, and faith-based and other community programs. Services for which the client reported receiving information, referral, counseling, or medication management for depression or emotional problems were classified as depression-related visits. We developed indicators for any service use and being above the baseline median visits and counts of contacts. Since a single overnight stay could reflect emergency room use, we included a sensitivity analyses having ≥ 4 hospital nights. To account for potential bias in self-report, we asked participants to provide names and addresses for up to four providers per sector; for high utilizers and “other” locations, we confirmed sector and count feasibility through Internet searches and calling programs.

Statistical Analysis

We conducted intent-to-treat analyses of repeated measures including all participants with available data at baseline, 6-, or 12-months using SAS version 9.2. Initial explorations of three-level, random effects logistic models using SAS proc glimmix for binary outcomes yielded unstable estimates for program-specific random effects (0-to-3 imputed data sets) suggesting that a random effects framework underestimated the variation between programs. We analyzed dichotomous and count outcomes using a generalized estimating equation (GEE) framework. Specifically, we fitted logistic regression models for binary outcomes and Poisson models for count data using SAS proc genmod, specifying exchangeable correlation at the program level, with regression adjustment for baseline covariates (age, sex, ≥ three chronic conditions, education, race/ethnicity, family poverty, 12-month alcohol abuse or use of illicit drugs, 12-month depressive disorder, and community). We then developed a contrast involving a linear combination of coefficients to test intervention effects at each endpoint (baseline, 6-, and 12-months) and tested differences between intervention arms in change from baseline to 6- and 12-months. The results of analyses of binary outcomes are presented as odds ratios (OR) and the results of Poisson regression analyses of count data are presented as rate ratios. We summarized effect sizes by presenting unadjusted means, proportions by intervention arm, and by standardized predictions (16,56) with associated confidence intervals for each outcome using a bootstrap procedure (57,58) (Appendix B). We treated time as a continuous variable and examined the fixed effects for time, intervention condition, and their interactions. We included quadratic terms (squared effect of time and its interaction with intervention condition), allowing insight into whether changes are greater from baseline to 6-months or subsequent months.

In analyzing continuously-scaled MCS-12 as the dependent variable, we used a three-level, mixed-effect regression model with SAS proc mixed. We accounted for the multi-level data structure with clients nested within programs and repeated measurements nested within clients. In order to account for the intra-class correlation expected in the data, we specified random effects at the program level and an autoregressive AR (1) covariance structure within clients to account for within-subject correlation over time.

We used item-level imputation for missing data and wave-level imputation for missing surveys to adjust findings to the observed analytic sample (n=1,018). In our prior outcome paper (30), we used weights to account for non-enrollment and nonresponse. In the current study, we used a model-based approach with unweighted data (56). As a result, this study's baseline and 6-months estimates differ slightly from prior reports (28,29). We conducted sensitivity analyses for alternative representations of time as a continuous or class variable and for alternative weighting approaches. To investigate possible non-ignorable effects, we used two methods. For continuous measures (e.g. MCS-12, # service visits), we multiplied for an ignorable-model imputations alternatively by 1.1 and 0.9 to reveal sensitivity to 10% departures from ignorable-model predictions with dichotomized versions of continuous measures (MCS-12≤40) based on the imputed continuous value. For categorical imputations where reference cells were based on an underlying continuous measure (i.e. predicted response propensity) including an indicator for any utilization and adjusted-Bayesian-bootstrap imputations reflecting unit nonresponse at a particular time point, non-ignorable imputations for cases in non-boundary reference cells were generated by borrowing values from the reference cell with either the next higher or next lower value of the underlying continuous measure (59).

Role of the Funding Sources

The National Institute of Mental Health, UCLA Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, National Library of Medicine, and California Community Foundation supported the study. The National Institute of Mental Health project officer served as an advisor to the Council, but otherwise, funders had no role in design, conduct, analysis, manuscript preparation or interpretation, or the decision to submit for publication.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

Of 1,018 depressed clients in 12-month outcome analyses, 58.4% were female, 88.1% were Latino or African American, 43.8% had less than a high school education, 73.7% had an income below the federal poverty level, 53.5% had no health insurance, and 20.1% were employed. The percentage with 12-month depressive disorder was 61.8%, while 39.1% had substance or alcohol abuse, and 53.8% had ≥ 3 chronic medical conditions (Table 1). As compared to RS, CEP had more Latinos and African Americans (85.9% vs. 90.2%, p=0.030). There were no other significant differences by intervention status in baseline characteristics.

Outcomes

In planned analyses comparing study endpoints, CEP as compared to RS significantly decreased the odds of reduced MHRQL at 6-months (p=0.009) and 12-months (p=0.028). (Table 2, Appendix Figure 1). In an analyses of change from baseline in likelihood of poor MHRQL, CEP also showed a significant advantage at 6-months (p=0.038), but not at 12-months. A modest degree of non-ignorability in imputations for missing data or changing the representation of time in statistical models from a continuous to a categorical variable affects interpretations, with most findings becoming either borderline significant or non-significant, but with a direction favoring CEP. Also sensitivity analyses reflecting MCS-12 on a continuous scale did not reveal any significant differences between interventions at 6- or 12-months. (Table 2, Appendix Figures 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Proportion of Clients with Poor Mental Health-related Quality of Life (MCS-12≤40) and Mean MCS-12 Score at 6- and 12-months by Intervention Condition, Raw Data and Alternative Analytic Models*

| Raw data | Primary Analysis† | Analysis with NMAR –higher value‡ |

Analysis with NMAR –lower value§ |

Analysis with categorical time value∥ |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | CEP | RS | CEP vs RS at specific time OR (CI) |

CEP vs RS in change from baseline OR (CI) |

CEP vs RS at specific time OR (CI) |

CEP vs RS in change from baseline OR (CI) |

CEP vs RS at specific time OR (CI) |

CEP vs RS in change from baseline OR (CI) |

CEP vs RS at specific time OR (CI) |

CEP vs RS in change from baseline OR (CI) |

|

| MCS-12≤40,n(%) | |||||||||||

| baseline | 962 | 257/479 (53.7%) | 259/483 (53.6%) | 1.00 (0.79, 1.28) | 0.97 (0.76, 1.25) | 1.03 (0.81, 1.31) | 1.00 (0.78, 1.27) | ||||

| 6 months | 755 | 166/376 (44.1%) | 198/379 (52.2%) | 0.71 (0.55, 0.91) | 0.71 (0.51, 0.98) | 0.73 (0.58, 0.93) | 0.75 (0.55, 1.04) | 0.79 (0.61, 1.02) | 0.77 (0.56, 1.07) | 0.72 (0.55, 0.95) | 0.73 (0.51, 1.04) |

| 12 months | 717 | 160/361 (44.3%) | 181/356 (50.8%) | 0.77 (0.61, 0.97) | 0.77 (0.55, 1.07) | 0.83 (0.66, 1.06) | 0.86 (0.61, 1.21) | 0.86 (0.67, 1.09) | 0.83 (0.59, 1.18) | 0.79 (0.59, 1.05) | 0.79 (0.56, 1.13) |

| MCS-12, mean (SD) | Group-difference | Group-difference in change from baseline | Group-difference | Group-difference in change from baseline | Group-difference | Group-difference in change from baseline | Group-difference | Group-difference in change from baseline | |||

| baseline | 962 | 39.2 (7.3) | 39.2 (7.5) | 0.12 (−0.82, 1.06) | 0.27 (−0.73, 1.26) | −0.02 (−0.96, 0.91) | 0.11 (−0.84, 1.05) | ||||

| 6 months | 755 | 40.3 (7.0) | 39.7 (7.4) | 0.60 (−0.36, 1.57) | 0.48 (−0.61, 1.58) | 0.68 (−0.35, 1.7) | 0.41 (−0.74, 1.56) | 0.53 (−0.41, 1.47) | 0.55 (−0.53, 1.63) | 0.61 (−0.51, 1.73) | 0.50 (−0.77, 1.77) |

| 12 months | 717 | 40.7 (7.0) | 40.4 (7.1) | 0.35 (−0.73, 1.44) | 0.23 (−1.21, 1.67) | 0.44 (−0.71, 1.58) | 0.17 (−1.37, 1.71) | 0.27 (−0.79, 1.33) | 0.29 (−1.10, 1.69) | 0.28 (−1.03, 1.60) | 0.18 (−1.43, 1.78) |

Note: Bold and italicized indicates p<.05. OR=odds ratio, CI=confidence interval, RS=resource for services, CEP=community engagement and planning, SD=Standard Deviation

Adjusted analyses used multiply imputed data n=1,018; a GEE logistic regression model for the binary variable, MCS-12≤40 (presented as odds ratio), and a three-level mixed-effect regression model for the continuous variable, MCS-12 score (presented as mean difference), adjusted for age, sex, ≥3 chronic conditions, education, race/ethnicity, income, family income < federal poverty level, 12-month alcohol abuse or use of illicit drugs, 12-month depressive disorder, and community.

time as continuous and multiple imputation procedures assume that the missing data are missing at random (MAR)

time as continuous and non-ignorable missing at random (NMAR) by multiplying the ignorable model's imputed data by 1.1

time as continuous and NMAR by multiplying the ignorable model's imputed data by 0.9

time as categorical variable with two indicators for 6- and 12-month time points and MAR

Service Utilization

Analyses comparing percentages of any behavioral health hospitalizations in the prior 6-months confirmed a significant reduction for CEP at 6-months (p=0.042) with no significant difference at 12-months (Table 3). Analyzed as change from baseline, CEP showed significant reductions in likelihood of behavioral health hospitalizations at 6-months (p=0.002) and at 12-months (p=0.002). At 6-months, qualitatively similar findings were observed for ≥ 4 behavioral health hospital nights, but at 12-months, the change from baseline was only borderline significant. No observed significant differences between intervention conditions on other services use measures were observed. For certain sectors (e.g. parks), there were too few users to develop reliable estimates of mean depression visits at 12-months. Sensitivity analyses with time as a class variable and varying imputed data assumptions confirmed favorable CEP effects at 6-months on any behavioral health hospitalizations and ≥4 behavioral health hospital nights, but all 12-month results on behavioral health hospitalizations were sensitive to analysis choices.

Table 3.

Services Utilizations at 6- and 12-months by Intervention Condition, Raw Data and Alternative Analytic Models*

| Raw data | Primary Analysis† | Analysis with NMAR –higher value‡ |

Analysis with NMAR –lower value§ |

Analysis with categorical time value∥ |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | CEP | RS | CEP vs RS at specific time OR (CI) |

CEP vs RS in change from baseline OR (CI) |

CEP vs RS at specific time OR (CI) |

CEP vs RS in change from baseline OR (CI) |

CEP vs RS at specific time OR (CI) |

CEP vs RS in change from baseline OR (CI) |

CEP vs RS at specific time OR (CI) |

CEP vs RS in change from baseline OR (CI) |

|

| Any behavioral health hospitalizations past 6 months, n(%) | |||||||||||

| baseline | 970 | 77/482 (16.0%) | 58/488 (11.9%) | 1.38 (0.91, 2.11) | 1.34 (0.89, 2.03) | 1.35 (0.88, 2.05) | 1.41 (0.93, 2.16) | ||||

| 6 months | 759 | 22/379 (5.8%) | 35/380 (9.2%) | 0.60 (0.37, 0.98) | 0.43 (0.26, 0.74) | 0.71 (0.42, 1.18) | 0.53 (0.31, 0.91) | 0.55 (0.24, 1.23) | 0.41 (0.19, 0.89) | 0.53 (0.30, 0.95) | 0.38 (0.20, 0.72) |

| 12 months | 731 | 18/367 (4.9%) | 17/364 (4.7%) | 0.70 (0.4, 1.22) | 0.51 (0.27, 0.96) | 0.79 (0.40, 1.55) | 0.59 (0.29, 1.18) | 0.65 (0.30, 1.41) | 0.48 (0.21, 1.09) | 0.92 (0.50, 1.66) | 0.65 (0.34, 1.24) |

| ≥4 behavioral health hospital nights, n(%) | |||||||||||

| baseline | 970 | 44/482 (9.1%) | 33/488 (6.8%) | 1.33 (0.85, 2.08) | 1.31 (0.82, 2.09) | 1.28 (0.82, 2.00) | 1.39 (0.87, 2.20) | ||||

| 6 months | 759 | 8/379 (2.1%) | 19/380 (5.0%) | 0.47 (0.23, 0.97) | 0.35 (0.17, 0.75) | 0.55 (0.27, 1.10) | 0.42 (0.21, 0.82) | 0.38 (0.16, 0.91) | 0.29 (0.12, 0.69) | 0.36 (0.16, 0.83) | 0.26 (0.10, 0.65) |

| 12 months | 730 | 10/367 (2.7%) | 9/363 (2.5%) | 0.7 (0.33, 1.48) | 0.52 (0.25, 1.11) | 0.79 (0.31, 2.00) | 0.60 (0.24, 1.50) | 0.57 (0.26, 1.26) | 0.45 (0.20, 1.00) | 1.01 (0.43, 2.34) | 0.73 (0.33, 1.58) |

| ≥2 emergency room visits, n(%) | |||||||||||

| baseline | 970 | 167/482 (34.6%) | 177/488 (36.3%) | 0.88 (0.62, 1.23) | 0.87 (0.62, 1.22) | 0.88 (0.63, 1.23) | 0.89 (0.63, 1.26) | ||||

| 6 months | 759 | 91/379 (24.0%) | 107/380 (28.2%) | 0.79 (0.57, 1.11) | 0.91 (0.6, 1.38) | 0.81 (0.59, 1.12) | 0.93 (0.64, 1.37) | 0.87 (0.61, 1.25) | 0.99 (0.67, 1.46) | 0.76 (0.52, 1.12) | 0.86 (0.53, 1.37) |

| 12 months | 730 | 75/367 (20.4%) | 88/363 (24.2%) | 0.75 (0.55, 1.03) | 0.86 (0.58, 1.27) | 0.77 (0.53, 1.11) | 0.88 (0.57, 1.37) | 0.77 (0.52, 1.14) | 0.87 (0.55, 1.38) | 0.77 (0.54, 1.10) | 0.87 (0.58, 1.30) |

| Any mental health outpatient visit, n(%) | |||||||||||

| baseline | 970 | 277/482 (57.5%) | 286/488 (58.6%) | 1.13 (0.73, 1.77) | 1.12 (0.72, 1.75) | 1.12 (0.72, 1.75) | 1.15 (0.74, 1.79) | ||||

| 6 months | 758 | 206/378 (54.5%) | 207/380 (54.5%) | 1.19 (0.78, 1.81) | 1.04 (0.69, 1.57) | 1.29 (0.80, 2.08) | 1.15 (0.72, 1.84) | 1.23 (0.81, 1.86) | 1.09 (0.72, 1.66) | 1.14 (0.76, 1.71) | 0.99 (0.67, 1.45) |

| 12 months | 728 | 165/366 (45.1%) | 163/362 (45.0%) | 1.05 (0.66, 1.66) | 0.92 (0.56, 1.52) | 1.20 (0.74, 1.93) | 1.06 (0.66, 1.71) | 1.04 (0.69, 1.55) | 0.92 (0.58, 1.47) | 1.08 (0.68, 1.73) | 0.94 (0.57, 1.54) |

| Any primary care visit, n(%) | |||||||||||

| baseline | 969 | 335/482 (69.5%) | 333/487 (68.4%) | 0.98 (0.68, 1.43) | 0.98 (0.67, 1.42) | 1.00 (0.69, 1.46) | 1.00 (0.69, 1.45) | ||||

| 6 months | 759 | 262/379 (69.1%) | 262/380 (68.9%) | 1.06 (0.76, 1.47) | 1.07 (0.78, 1.48) | 1.11 (0.78, 1.57) | 1.13 (0.79, 1.62) | 1.08 (0.70, 1.68) | 1.08 (0.71, 1.64) | 0.98 (0.66, 1.46) | 0.99 (0.67, 1.46) |

| 12 months | 729 | 263/366 (71.9%) | 231/363 (63.6%) | 1.31 (0.98, 1.76) | 1.33 (0.9, 1.99) | 1.38 (1.03, 1.86) | 1.41 (0.97, 2.05) | 1.33 (0.90, 1.97) | 1.33 (0.83, 2.13) | 1.44 (1.05, 1.99) | 1.45 (0.94, 2.23) |

| Any primary care visit with depression service, n(%) | |||||||||||

| baseline | 952 | 195/472 (41.3%) | 196/480 (40.8%) | 0.93 (0.66, 1.31) | 0.95 (0.67, 1.34) | 0.95 (0.68, 1.33) | 0.94 (0.66, 1.34) | ||||

| 6 months | 756 | 117/377 (31.0%) | 111/379 (29.3%) | 1.05 (0.77, 1.45) | 1.13 (0.82, 1.56) | 1.14 (0.82, 1.58) | 1.20 (0.86, 1.67) | 1.17 (0.83, 1.66) | 1.24 (0.89, 1.72) | 0.96 (0.66, 1.38) | 1.02 (0.68, 1.52) |

| 12 months | 728 | 106/366 (29.0%) | 89/362 (24.6%) | 1.03 (0.74, 1.42) | 1.10 (0.74, 1.65) | 1.13 (0.81, 1.57) | 1.19 (0.80, 1.76) | 1.10 (0.78, 1.54) | 1.16 (0.78, 1.73) | 1.12 (0.79, 1.58) | 1.19 (0.79, 1.80) |

| # of counseling visits from mental health specialty or primary care, mean (SD) | |||||||||||

| baseline | 948 | 7.3 (13.7) | 6.4 (3.8) | 1.11 (0.81, 1.52) | 1.12 (0.81, 1.53) | 1.10 (0.80, 1.51) | 1.13 (0.83, 1.54) | ||||

| 6 months | 755 | 7.1 (12.5) | 8.8 (22.9) | 0.73 (0.45, 1.19) | 0.66 (0.41, 1.06) | 0.73 (0.44, 1.21) | 0.65 (0.40, 1.07) | 0.74 (0.46, 1.17) | 0.67 (0.43, 1.05) | 0.70 (0.43, 1.15) | 0.62 (0.38, 1.01) |

| 12 months | 724 | 4.7 (10.3) | 5.1 (11.2) | 0.87 (0.58, 1.3) | 0.78 (0.51, 1.21) | 0.88 (0.58, 1.32) | 0.79 (0.50, 1.23) | 0.86 (0.58, 1.28) | 0.78 (0.51, 1.19) | 0.96 (0.64, 1.43) | 0.85 (0.53, 1.35) |

| Any faith-based program participation, n(%) | |||||||||||

| baseline | 967 | 280/481 (58.2%) | 299/486 (61.5%) | 0.84 (0.62, 1.14) | 0.83 (0.60, 1.13) | 0.81 (0.58, 1.13) | 0.83 (0.61, 1.14) | ||||

| 6 months | 759 | 217/379 (57.3%) | 229/380 (60.3%) | 0.84 (0.6, 1.17) | 1 (0.72, 1.4) | 0.81 (0.56, 1.16) | 0.98 (0.68, 1.42) | 0.82 (0.59, 1.13) | 1.01 (0.70, 1.46) | 0.83 (0.62, 1.12) | 1.00 (0.71, 1.40) |

| 12 months | 729 | 195/366 (53.3%) | 214/363 (59.0%) | 0.79 (0.6, 1.05) | 0.95 (0.67, 1.34) | 0.73 (0.54, 0.98) | 0.88 (0.62, 1.25) | 0.81 (0.60, 1.10) | 1.01 (0.70, 1.44) | 0.80 (0.58, 1.11) | 0.96 (0.66, 1.39) |

| Any use of parks or community centers, n(%) | |||||||||||

| baseline | 967 | 225/481 (46.8%) | 239/486 (49.2%) | 0.88 (0.67, 1.16) | 0.90 (0.68, 1.20) | 0.90 (0.68, 1.19) | 0.91 (0.69, 1.20) | ||||

| 6 months | 759 | 150/379 (39.6%) | 161/380 (42.4%) | 1.00 (0.72, 1.39) | 1.14 (0.83, 1.55) | 1.00 (0.73, 1.38) | 1.11 (0.82, 1.50) | 1.04 (0.76, 1.43) | 1.16 (0.80, 1.67) | 0.90 (0.61, 1.33) | 0.99 (0.67, 1.46) |

| 12 months | 730 | 132/366 (36.1%) | 133/364 (36.5%) | 0.97 (0.72, 1.32) | 1.10 (0.79, 1.53) | 0.99 (0.70, 1.41) | 1.10 (0.80, 1.51) | 1.00 (0.73, 1.38) | 1.12 (0.78, 1.60) | 1.05 (0.76, 1.45) | 1.15 (0.81, 1.65) |

| Took antidepressant ≥2 months past 6 months, n(%) | |||||||||||

| baseline | 945 | 151/471 (32.1%) | 145/474 (30.6%) | 1.30 (0.86, 1.96) | 1.27 (0.83, 1.92) | 1.28 (0.85, 1.92) | 1.30 (0.87, 1.96) | ||||

| 6 months | 757 | 125/377 (33.2%) | 149/380 (39.2%) | 0.91 (0.55, 1.5) | 0.7 (0.45, 1.08) | 1.02 (0.62, 1.67) | 0.81 (0.55, 1.18) | 0.93 (0.62, 1.40) | 0.73 (0.51, 1.03) | 0.86 (0.50, 1.47) | 0.66 (0.40, 1.08) |

| 12 months | 730 | 108/366 (29.5%) | 123/364 (33.8%) | 0.87 (0.55, 1.39) | 0.67 (0.43, 1.04) | 0.90 (0.59, 1.39) | 0.71 (0.48, 1.06) | 0.87 (0.57, 1.34) | 0.68 (0.42, 1.11) | 0.93 (0.60, 1.44) | 0.72 (0.47, 1.10) |

| Total outpatient contacts for depression, mean (SD) | |||||||||||

| baseline | 929 | 28.2 (54.5) | 30.4±51.0 | 0.93 (0.68, 1.26) | 0.93 (0.69, 1.27) | 0.92 (0.68, 1.26) | 0.93 (0.68, 1.27) | ||||

| 6 months | 759 | 21.6 (43.9) | 21.0±46.8 | 0.96 (0.6, 1.53) | 1.03 (0.65, 1.64) | 0.95 (0.58, 1.56) | 1.02 (0.63, 1.67) | 0.96 (0.62, 1.51) | 1.04 (0.67, 1.62) | 0.95 (0.57, 1.56) | 1.02 (0.62, 1.69) |

| 12 months | 719 | 18.0 (40.4) | 19.4±43.6 | 0.91 (0.65, 1.29) | 0.99 (0.69, 1.41) | 0.92 (0.65, 1.30) | 0.99 (0.69, 1.41) | 0.91 (0.64, 1.29) | 0.99 (0.69, 1.42) | 0.93 (0.64, 1.36) | 1.01 (0.69, 1.47) |

Note: Bold and italicized indicates p<.05. OR=odds ratio, CI=confidence interval, RS=resource for services, CEP=community engagement and planning. SD=standard deviation.

Adjusted analyses used multiply imputed data n=1,018; a GEE logistic regression model for a binary variable (presented as odds ratio) and a GEE Poisson regression model for a count variable (presented as rate ratio) adjusted for age, sex, ≥3 chronic conditions, education, race/ethnicity, family income < federal poverty level, 12-month alcohol abuse or use of illicit drugs, 12-month depressive disorder, and community.

time as continuous and multiple imputation procedures assume that the missing data are missing at random (MAR)

time as continuous and non-ignorable missing at random (NMAR) by multiplying the ignorable model's imputed data by 1.1

time as continuous and NMAR by multiplying the ignorable model's imputed data by 0.9

time as categorical variable with two indicators for 6- and 12-month time points and MAR

DISCUSSION

Although the significance of study findings were sensitive to underlying statistical assumptions and although CEP effects were not significant using a continuous MCS-12 score, CEP was found to have advantages over RS in several analyses in reducing the likelihood of poor mental health-related quality of life (MCS-12≤40), the primary outcome for depressed clients from healthcare and social-community programs in under-resourced, Los Angeles communities of color. Evidence of persistence of CEP intervention effects at 12-months is less clear with greater sensitivity of findings to underlying statistical assumptions.

Our analyses confirm CEP's effect on reducing behavioral hospitalizations at 6-months (30), but the significance of a similar effect from baseline to 12-months is more speculative due to sensitivity to statistical methods. We found no significant differences by intervention status on utilization variables including healthcare-based depression treatments (medication or counseling). For some sectors (e.g. parks), depression services users were too few to estimate differences in mean visits. Overall, the shift of outpatient visits toward alternative sectors reported at 6-months was not apparent at 12-months (30). Also, we note that baseline findings reported here differ slightly from prior publications, due to differences in weighting and statistical analysis procedures (29,30).

CEP effects at 12-months may have been due to decreased intervention support after the first 6-months or the variable level of program CEP implementation resulting in clients with positive outcomes being outweighed by clients with no evidence of positive outcomes. Future research should examine whether additional implementation support would offer more consistent evidence of sustained CEP effects beyond 6-months.

The study has important limitations. We did not have a usual-care arm, but compared two active interventions that are each likely to be effective relative to usual care. We did not have data on hospitalization and medication use for general health conditions other than behavioral health. Because our sample includes only 1,018 clients, precision was low for definitive service use estimates. The study was conducted in two Los Angeles communities where study leaders have a long history of applying CPPR to depression (61-65). It is unknown whether applying this approach in communities without this history would yield similar effects. Response rates were moderate for agencies and high for programs. Although initial client enrollment rates were high, retention was lower relative to other depression QI studies but comparable to studies of clients in safety-net settings (66,67). Client outcomes relied on self-report data and clinical process data linking programs to clients were unavailable. We have not adjusted significance for multiple comparisons because, as noted in our protocol, we focused on one primary outcome, poor MHRQL. The significance of CEP effects was sensitive to underlying statistical assumptions of representation of time in models (i.e. class or continuous variable); to possible departures from non-ignorable model predictions for imputed values; and to whether we used a GEE longitudinal analysis with an exchangeable working correlation assumption or a design-based analysis using SUDAAN to incorporate sampling and non-response weights for 12-month outcomes (Appendix B, Table B8).

Our results confirm CEP's short-term effect on reducing the percentage of depressed client's with poor MHRQL and behavioral health hospitalizations at 6-months, with less evident effects at 12-months. Short-term change in avoiding poor quality of life and behavioral health hospitalizations, and possibly longer term, are clinically important due to consistent mental health disparities (3-5), depression-related costs (68,69), and depression's recurrent chronicity (70,71). Given under-resourced communities’ unmet needs, the absence of evidence-based alternatives, CEP's modestly favorable profile and limited risk, community engagement remains a viable strategy for policymakers and communities to consider for depression collaborative care implementation (72) to improve population-based health outcomes for vulnerable individuals.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the 25 participating agencies of the Council and their representatives: QueensCare Health and Faith Partnership; COPE Health Solutions; UCLA Center for Health Services and Society; Cal State University Dominquez Hills; RAND; Healthy African American Families II; Los Angeles Urban League; Los Angeles Christian Health Centers; Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health and West Central Mental Health Center; Homeless Outreach Program/Integrated Care System; National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) Urban Los Angeles; Behavioral Health Services, Inc.; Avalon Carver Community Center; USC Keck School of Medicine Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences; Kaiser Watts Counseling and Learning Center; People Assisting the Homeless; Children's Bureau; Saban Free Clinic; New Vision Church of Jesus Christ; Jewish Family Services of Los Angeles; St. John's Well Child and Family Center; Charles Drew University of Medicine and Science; City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks; To Help Everyone Clinic; QueensCare Family Clinics, the National Institute of Mental Health, the UCLA Clinical and Translational Science Institute, the California Community Foundation, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

We thank the Los Angeles programs, providers and staff, and clients who participated. We thank the RAND Survey Research Group and community members who conducted client data collection. We thank Loretta Jones for her study leadership and vision; Esmeralda Pulido, Ana Ramos, Rosie Cardenas, and Liz Lizaola for project management support; Lily Zhang for statistical programming support; Ira Lesser, Charles Grob, and Christina Wang for support at Harbor-UCLA/Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute and UCLA CTSI for analyses and manuscript preparation support. We thank Paul Steinberg, Marcia Meldrum, and David Miklowitz for support during manuscript revisions.

Funding Support: Award Numbers R01MH078853, P30MH082760, and P30MH068639 from the National Institute of Mental Health, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (64244), California Community Foundation, National Library of Medicine Award Number G08LM011058, and the NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Science UCLA CTSI Award Number UL1TR000124.

Appendix

Appendix Table 1.

CPIC Intervention and Training Features by Condition

| Resources for Services (RS) | Community Engagement and Planning (CEP) | |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Model | 1)Depression care collaborative care toolkit (manuals, slides, medication pocket cards, patient education brochures and videos) via print, flash drives, and website. 2)Trainings via 12 webinars / conference calls to all programs and site visits to primary care 3)Expert trainers: nurse care manager, licensed psychologist cognitive behavioral therapy trainer, three board-certified psychiatrists for medication management, experienced community service administrator supporting cultural competence and participation 4)Community engagement specialist for up to 5 outreach calls to encourage participation and fit toolkits to programs 5)Study paid for trainings and materials at $16,333 per community. |

1) Depression care collaborative care toolkit (manuals, slides, medication pocket cards, patient education brochures and videos) via print, flash drives, and website. 3)Expert trainers: nurse care manager, licensed psychologist cognitive behavioral therapy trainer, three board-certified psychiatrists for medication management, experienced community service administrator supporting cultural competence and participation 4)5 months of 2-hour, bi-weekly planning meetings for a CEP councils to tailor materials and develop and implement a written training and depression service delivery plan for each community, guided by a manual and community engagement model. The goal of the plan was to support increased capacity for depression care through collaboration across a myriad of community programs. 5)Co-leadership by study Council following community engagement and social justice principles to encourage collaboration and network building 6)$15,000 per community for consultations and training modifications |

| Implemented | ||

| Overall | 21 Webinars and 1 primary care site visit | Multiple one-day conferences with follow-up trainings at sites; webinar and telephone-based supervision |

| Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and clinical assessment | Manuals (Individual and group) and 4 webinars offered for licensed physicians, psychologists, social workers, nurses marriage and family therapists | 1)Manuals (Individual and group) 2)Tiers of training: For licensed providers plus substance abuse counselors: a) intensive CBT support included feedback on audiotaped therapy session with one to two depression cases for 12-16 weeks, b) 10 week webinar group consultation, and for any staff trainee, c) Orientation workshops for concepts and approaches. |

| Case management | Manuals, 4 webinars and resources for depression screening, assessment of comorbid conditions, client education and referral, tracking visits to providers, medication adherence, and outcomes, and introduction to problem solving therapy and/ behavioral activation; for nurses, case workers, health educators, spiritual advisors, promotoras, lay counselors | 1)Manuals 2)In-person conferences, individual agency site visits, and telephone supervision for the same range of providers. 3) Modifications included a focus on self-care for providers, simplification of materials such as fact sheets and tracking with shorter outcome measures. Similar range of providers and staff as RS. 3)Training in active listening in one community; training of volunteers to expand capacity in one community 4)Development of an alternative “resiliency class” approach to support wellness for Village Clinic |

| Medication and clinical assessment | 1)Manuals, medication pocket cards. 2)For MD, Nurses, Nurse practitioners, physician's assistants; training in medication management and diagnostic assessment; webinar and in-person site visit to primary care |

1)Manuals, medication pocket cards. 2)Two-tiered approach with training for medication management and clinical assessment coupled with information on complementary / alternative therapies and prayer for depression, through training slides; and second tier of orientation to concepts for lay providers. |

| Administrators/Other | Webinar on overview of intervention plan approaches to team building/management and team-building resources | 1)Conference break-outs for administrators on team management and building and team –building resources; support for grant-writing for programs 2)Administrative problem-solving to support “Village Clinic” including option of delegation of outreach to clients from RAND survey group, identification of programs to support case management, resiliency classes, and CBT for depression |

| Training events | 21 webinars and 1 site visit (22 hours) (combined communities) CBT (8 hours) Care management (8 hours) Medication (1 hours) Implementation support for Administrators (5 hours) |

144 training events (220.5 total hours) (combined communities) CBT (135 hours) Care Management (60 hours) Medication (6 hours) Other Skills (19.5 hours) |

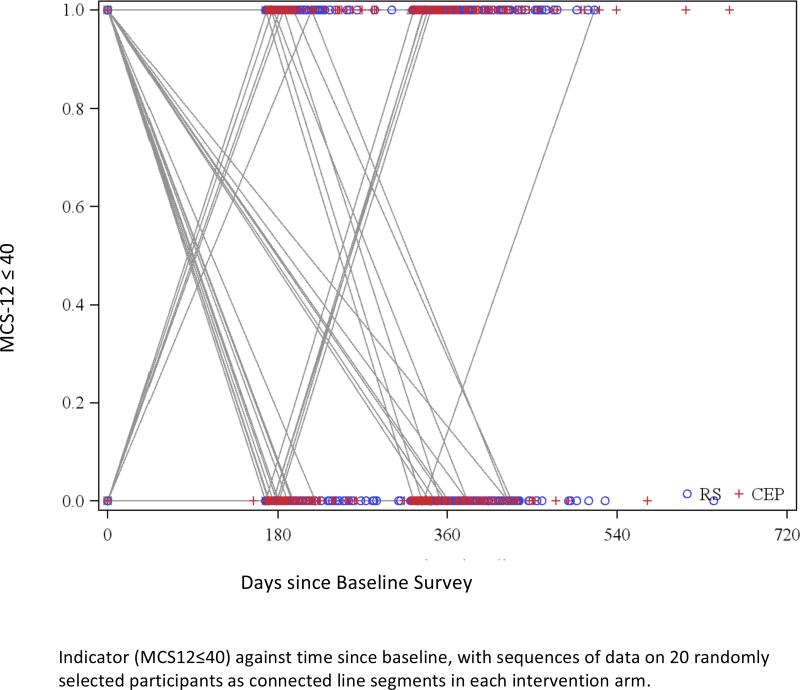

Appendix Figure 1.

Percentage of Clients with Poor Mental Health-Related Quality of Life (MCS-12≤40) at baseline, 6, and 12-months by Intervention Condition

Appendix Figure 2.

Mean MCS-12 score at baseline, 6, and 12-months by Intervention Condition

Appendix Figure 3.

Mean MCS-12 Score by Number of Days from Baseline Survey by Intervention Condition.

Appendix Figure 4.

Scatterplot of indicator (MCS-12≤40)by number of days from baseline survey by Intervention Condition.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTACT INFORMATION

Michael Ong, MD, PhD, Division of General Internal Medicine and Health Services Research, 10940 Wilshire Blvd, BOX 957394, 10940 Wilshire Blvd. Ste 700, Los Angeles, CA 90095-7394

Felica Jones, Healthy African American Families II, 4305 Degnan Blvd, Suite 105, Los Angeles, CA 90008

James Gilmore, MBA, Behavioral Health Services, 15519 Crenshaw Blvd, Gardena, CA 90249

Michael McCreary, MPP, Center for Health Services and Society, Semel Institute for Neuroscience, Box 957082, 10920 Wilshire Blvd, Suite 300, Los Angeles, CA 90095-7082

Cathy Sherbourne, PhD, RAND Corporation, 1776 Main Street, P.O. Box 2138, Santa Monica, CA 90407-2138

Victoria Ngo, PhD, RAND Corporation, 1776 Main Street, P.O. Box 2138, Santa Monica, CA 90407-2138

Paul Koegel, PhD, RAND Corporation, 1776 Main Street, P.O. Box 2138, Santa Monica, CA 90407-2138

Lingqi Tang, PhD, Center for Health Services and Society, Semel Institute for Neuroscience, Box 957082, 10920 Wilshire Blvd, Suite 300, Los Angeles, CA 90095-7082

Elizabeth Dixon, PhD, UCLA School of Nursing, BOX 956919, 5-660 Factor, Los Angeles, CA 90095-6919

Jeanne Miranda, PhD, Center for Health Services and Society, Semel Institute for Neuroscience, Box 957082, 10920 Wilshire Blvd, Suite 300, Los Angeles, CA 90095-7082

Thomas R. Belin, PhD, UCLA School of Public Health, Department of Biostatistics, BOX 951772, 51-267 CHS, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1772

Kenneth B. Wells, MD, MPH, Center for Health Services and Society, Semel Institute for Neuroscience, Box 957082, 10920 Wilshire Blvd, Suite 300, Los Angeles, CA 90095-7082

Study registered at Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01699789).

Reproducible Research Statement

Protocol: available at http://hss.semel.ucla.edu/documents/CPIC_Protocol_Dec2012.pdf.

Statistical code: available to interested readers by contacting Lingqi Tang, PhD at lqtang@ucla.edu

Data: available upon request by contacting Lingqi Tang, PhD at lqtang@ucla.edu

REFERENCES

- 1.Insel TR, Charney DS. Research on major depression. JAMA. 2003;289(23):3167–3168. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler R, Chiu W, Demler O, Merikangas K, Walters E. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 Jun;62(6):617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonzalez H, Vega W, Williams D, Tarraf W, West B, Neighbors H. Depression care in the United States: too little for too few. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010 Jan;67(1):37–46. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gonzalez HM, Tarraf W, Whitfield KE, Vega WA. The epidemiology of major depression and ethnicity in the United States. J Psychiatr Res. 2010 Nov;44(15):1043–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGuire T, Miranda J. New evidence regarding racial and ethnic disparities in mental health: policy implications. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(2):393–403. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miranda J, McGuire T, Williams D, Wang P. Mental health in the context of health disparities. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(9):1102–1108. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang P, Berglund P, Kessler R. Recent care of common mental disorders in the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;15(5):284–292. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.9908044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang P, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus H, Wells K, Kessler R. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):629. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams D, Gonzalez H, Neighbors H, et al. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites: results from the National Survey of American Life. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007 Mar;64(3):305–315. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asarnow J, Jaycox L, Duan N, LaBorde AP, Rea MM, Murray P, et al. Effectiveness of a quality improvement intervention for adolescent depression in primary care clinics. JAMA. 2005;293(3):311–319. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton A. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(21):2314. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilbody S, Whitty P, Grimshaw J, Thomas R. Educational and organizational interventions to improve the management of depression in primary care. JAMA. 2003;289(23):3145–3151. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katon W, Lin E, Von Korff M, Ciechanowski P, Ludman EJ, Young B, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2611–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan C, Williams JW, Hunkler E, Harpole L, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wells K, Tang L, Miranda J, Benjamin B, Duan N, Sherbourne C. The effects of quality improvement for depression in primary care at nine years: results from a randomized, controlled group-level trial. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(6):1952–1974. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00871.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, Duan N, Meredith L, Unutzer J, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283(2):212–220. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miranda J, Chung JY, Green BL, Krupnik J, Siddique J, Revicki DA, et al. Treating depression in predominantly low-income young minority women. JAMA. 2003;290(1):57–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, Ettner S, Buan N, Miranda J, et al. Five-year impact of quality improvement for depression: results of a group-level randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(4):378–86. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rieselbach RE, Crouse BJ, Frohna JG. Teaching primary care in community health centers: addressing the workforce crisis for the underserved. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:118–22. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Association of Community Health Centers and Robert Graham Center . Access granted: the primary care payoff. National Association of Community Health Centers and Robert Graham Center; Washington (DC): 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Association of Community Health Centers and Robert Graham Center . National Association of Community Health Centers and Robert Graham Center; Washington (DC): 2007. Access denied. [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Research Council . Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies from Social and Behaviorla Research. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas SB, Quinn SC, Butler J, Fryer CS, Garza MA. Toward a fourth generation of disparities research to achieve health equity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:399–416. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry [March 30, 2014];CTSA community engagement key function committee task force on the principles of community engagement (second edition) 2011 http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pce_ctsa.html.

- 25.Institute of Medicine . Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care (full printed version) The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Institute of Medicine . The CTSA Program at NIH: Opportunities for Advancing Clinical and Translational Research. The National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.: 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chung B, Dixon E, Miranda J, Wells K, Jones L. Using a community partnered participatory research approach to implement a randomized controlled trial: planning Community Partners in Care. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(3):780–795. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miranda J, Ong M, Jones L, Chung B, Dixon EL, Tang L, et al. Community-Partnered Evaluation of Depression Services for Clients of Community-Based Agencies in Under-Resourced Communities in Los Angeles. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(10):1268–78. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2480-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wells K, Jones L, Chung B, Dixon EL, Tang L, Gilmore J, et al. Community-Partnered Cluster-Randomized Comparative Effectiveness Trial of Community Engagement and Planning or Resources for Services to Address Depression Disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(10):1268–78. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2484-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mango J, Cabiling E, Wright A, Jones F, Jones L, Ramos A, et al. Community Partners in Care (CPIC): Video Summary of Rationale, Study Approach / Implementation, and Client 6-month Outcomes. CES4Health.info. 2014 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang ET, Gilmore J, Tang L, Morgan A, Wells KB, Chung B. Comorbid Depression and Substance Abuse in Safety-net Clients of Health and Community-based Agencies in Los Angeles: Clinical Needs and Service Use Patterns. Findings from Community Partners in Care. Psychiatr Serv. 2014 doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300318. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. JAMA. 2007;297(4):407–410. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones L, Meade B, Forge N, et al. Begin your partnership: The process of engagement. Ethn Dis. 2009;19:S6–8-16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones L, Wells K, Norris K, Meade B, Koegel P. The vision, valley, and victory of community engagement. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(4 Suppl 6):S6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wells K, Jones L. Commentary: “research” in community-partnered, participatory research. JAMA. 2009;302(3):320–321. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Ann Rev Public Health. 1998;19(1):173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khodyakov D, Mendel P, Dixon E, Jones A, Masongsong Z, Wells K. Community partners in care: leveraging community diversity to improve depression care for underserved populations. Int J Divers Organ Communities Nations. 2009;9(2):167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mendel P, Ngo V, Dixon E, Stockdale S, Jones F, Chung B, et al. Partnered evaluation of a community engagement intervention: use of a kickoff conference in a randomized trial for depression care improvement in underserved communities. Ethn Dis. 2011:21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Los Angeles County Department of Health Services . LA County Department of Health Services Key Health Indicators. Los Angeles, CA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 41.US Census Bureau . Los Angeles County; California: [June 23, 2012]. http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/06/06037.html. [Google Scholar]

- 42.California Pan-Ethnic Health Network . Los Angeles County multicultural health fact sheet. California Pan-Ethnic Health Network; Los Angeles: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murray DM. Design and analysis of group-randomized trials. Oxford University Press; USA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Belin TR, Stockdale S, Tang L, Jones F, Jones A, Wright A, et al., editors. Developing a randomization protocol in a community-partnered participatory research project to reduce the burden of depression.. Proceedings of the American Statistical Association Health Policy Statistics Section; Alexandria Virginia. 2010.pp. 5165–5171. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale, New Jersey: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kish L. Survey sampling. New York: Wiley. 1965 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32(9):509–15. [Google Scholar]

- 48. [04/01/2014];Community Partners in Care Depression Care Toolkit. www.communitypartnersincare.org.

- 49.Rubenstein LV, Jackson-Triche M, Unutzer J, et al. Evidence-based care for depression in managed primary care practices. Health Aff (Millwood) 1999 Sep-Oct;18(5):89–105. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.5.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wennerstrom A, Vannoy SD, 3rd, Allen CE, Meyers D, O'Toole E, Wells KB, et al. Community-based participatory development of a community health worker mental health outreach role to extend collaborative care in post-Katrina New Orleans. Ethn Dis. 2011;21(3 Suppl 1):S1–45-51. Summer. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bentham W, Vannoy SD, Badger K, Wennerstrom A, Springgate BF. Opportunities and challenges of implementing collaborative mental health care in post-Katrina New Orleans. Ethn Dis. 2011;21(3 Suppl 1):S1–30-37. Summer. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ware J, Jr, Sherbourne C. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ware J, Kosinski M, Turner-Bowker D, Gandek B. How to Score Version 2 of the SF-12 Health Survey (With a Supplement Documenting Version 1) QualityMetric Inc; Lincoln, RI: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 54. [April 14, 2014];The HHS Poverty Guidelines for the Remainder of 2010. 2010 Aug; http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/10poverty.shtml.

- 55.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Korn E, Graubard B. Analysis of Health Surveys. Wiley-Interscience; Hoboken, New Jersey: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Davison AC, Hinkley DV. Bootstrap methods and their applications 1st edition. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Efron B, Tibshirani R. An introduction to the Bootstrap 1st edition. Chapman & Hall; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Belin TR, Hu MY, Young AS, Grusky O. Performance of a general location model with an ignorable missing-data assumption in a multivariate mental health services study. Statist, Med. 1999;18:3123–3135. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19991130)18:22<3123::aid-sim277>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chung B, Jones L, Jones A, et al. Using community arts events to enhance collective efficacy and community engagement to address depression in an African American community. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(2):237. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.141408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chung B, Jones L, Terry C, Jones A, Forge N, Norris KC. Story of Stone Soup: a recipe to improve health disparities. Ethn Dis. 2010;20(1 Suppl 2):S2–9-14. Winter. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bluthenthal R, Jones L, Fackler-Lowrie N, et al. Witness for Wellness: preliminary findings from a community-academic participatory research mental health initiative. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(Suppl):S18–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Patel KK, Koegel P, Booker T, Jones L, Wells K. Innovative approaches to obtaining community feedback in the Witness for Wellness experience. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1):1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chung B, Corbett CE, Boulet B, et al. Talking wellness: a description of a community-academic partnered project to engage an African-American community around depression through the use of poetry, film, and photography. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1):1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jones D, Franklin C, Butler BT, Williams P, Wells KB, Rodriguez MA. The Building Wellness Project: a case history of partnership, power sharing, and compromise. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1):1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ell K, Xie B, Quon B, Quinn DI, Dwight-Johnson M, Lee PJ. Randomized controlled trial of collaborative care management of depression among low-income patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(27):4488–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.6371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Miranda J, Green BL, Krupnick JL, Chung J, Siddique J, Belin T, et al. One-year outcomes of a randomized clinical trial treating depression in low-income minority women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(1):99. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mrazek DA, Hornberger JC, Altar A, Degtlar I. A Review of the Clinical, Economic, and Societal Burden of Treatment-Resistant Depression: 1996-2013. Psychiatr Serv. Aug 1. 2014;65(8):977–87. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jacob V, Chattopadhyay S, Sipe T, Thota A, Byard G, Chapman D. Economics of collaborative care for management of depressive disorders: a community guide systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2012 May;42(5):539–549. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang JL, Patten S, Sareen J, Bolton J, Schmitz N, MacQueen G. Development and validation of a prediction algorithm for use by health professionals in prediction of recurrence of major depression. Depress Anxiety. May. 2014;31(5):451–7. doi: 10.1002/da.22215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kessler RC, Bromet EJ. The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annu Rev Public Health. 2013;34:119–38. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.SAMSHA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions [March 4, 2014];Behavioral Health Homes for People with Mental Health and Substance Use Conditions: Core Clinical Features. 2012 http://www.integration.samhsa.gov/integrated-care-models/health-homes.