Abstract

Prions exist as different strains exhibiting distinct disease phenotypes. Currently, the identification of prion strains is still based on biological strain typing in rodents. However, it has been shown that prion strains may be associated with distinct PrPSc biochemical types. Taking advantage of the availability of several prion strains adapted to a novel rodent model, the bank vole, we investigated if any prion strain was actually associated with distinctive PrPSc biochemical characteristics and if it was possible to univocally identify strains through PrPSc biochemical phenotypes. We selected six different vole-adapted strains (three human-derived and three animal-derived) and analyzed PrPSc from individual voles by epitope mapping of protease resistant core of PrPSc (PrPres) and by conformational stability and solubility assay. Overall, we discriminated five out of six prion strains, while two different scrapie strains showed identical PrPSc types. Our results suggest that the biochemical strain typing approach here proposed was highly discriminative, although by itself it did not allow us to identify all prion strains analyzed.

Keywords: prion, prion strain, TSE, PrPSc, bank vole, CJD, scrapie, BSE, conformational stability, GdnHCl

1. Introduction

Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), or prion diseases, are neurodegenerative disorders that afflict humans and others mammals. Prion diseases may be caused by prion exposure (acquired forms), mutations in PRNP gene (genetic or hereditary forms) and sporadic events in which the source of infection has not yet been demonstrated (idiopathic or sporadic forms). They include sporadic and genetic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD and gCJD) in humans, scrapie in sheep and goats and bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in cattle.

All TSEs are characterized by the accumulation of PrPSc, the pathological form of host encoded prion protein (PrPC), considered to be the main or sole component of infectious agent termed prion, according to the protein-only hypothesis [1].

Prions exist as different strains that, when propagated in the same host, exhibit distinct disease phenotypes that persist upon serial transmissions [2,3]. Within the context of the protein-only hypothesis, it has been suggested that prion strain diversity is encrypted in distinct conformations of PrPSc aggregates [4].

Although the identification of prion strains is still based on biological strain typing in rodents, several studies showed that prion strains can be distinguished based on different biochemical properties of PrPSc: the electrophoretic features of the protease resistant core of PrPSc [5,6,7], the relative proteinase K resistance of PrPSc [8,9], or the physico-chemical behavior of PrPSc during denaturation [10,11,12]. Indeed, such biochemical discrimination allowed large scale testing of small ruminants TSEs in EU in order to recognize the possible presence of BSE [13,14,15,16,17]. Notwithstanding, no unequivocal relationship between type of PrPSc and strain has been demonstrated so far, possibly due to technical difficulties which do not allow the direct structural analysis of PrPSc aggregates, or due to the presence of still unidentified strain-specific co-factors [18].

Further drawbacks may derive by PrPres-based approaches, as these are focused on the PK-resistant core of PrPSc (PrPres), while it is becoming increasingly clear that protease-sensitive isoforms of PrP are involved in different animal and human prion diseases [12,19,20,21,22,23]. These findings led us to develop a new method (CSSA) which does not rely on the protease resistant PrPSc but allows us to study the conformational properties of both protease sensitive and protease-resistant PrPSc species [11].

We have shown that bank voles (Myodes glareolus) are susceptible to a wide range of prion sources [24,25,26,27,28,29]. Taking advantage of vole-adapted prion strains, this study aimed at investigating if any different strain is actually associated with distinctive PrPSc types and if it might be possible to unequivocally identify strain through these biochemical phenotypes. We selected vole-adapted human and animal strains including gCJD and sCJD subtypes, sheep classical scrapie and bovine BSE. PrPSc from voles was analyzed by semi-quantitative western blot after PK digestion (PrPres) and after denaturation with increasing GdnHCl concentrations and PrPC/PrPSc differential centrifugation (conformational stability and solubility assay).

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Selection of Vole-Adapted Strains

As previously reported, the bank voles are susceptible to a wide range of prion sources: human sCJD and gCJD [24,25], sheep scrapie [26,27], cattle and sheep BSE [24,28], cervid Chronic Wasting Disease [29] and mouse- and hamster-adapted scrapie strains [24,30]. With the aim of studying the strain-specific biochemical features of PrPSc, we selected 43 brain tissues from 10 vole-adapted isolates representative of six different vole-adapted prions strains, three human-derived and three animal-derived: (i) sCJD MM1, MV1 and gCJD E200K, all belonging to the same vole-adapted strain “CJD type 1” [24]; (ii) sCJD MM2 [24]; (iii) sCJD MV2; (iv) Italian sheep scrapie SS7 [26]; (v) UK sheep scrapie isolates SCR1, SCR10 and SCR11 [26,31] which all gave in vole the same scrapie strain, “UK85”, different from that derived from Italian scrapie isolates, It93; (vi) bovine BSE [28]. With the exception of sCJD MV2, SCR1, SCR10 and SCR11, which will be reported elsewhere (manuscript in preparation), the transmission features of all these isolates (attack rates, survival times and lesion profiles), have been previously reported [24,26,28].

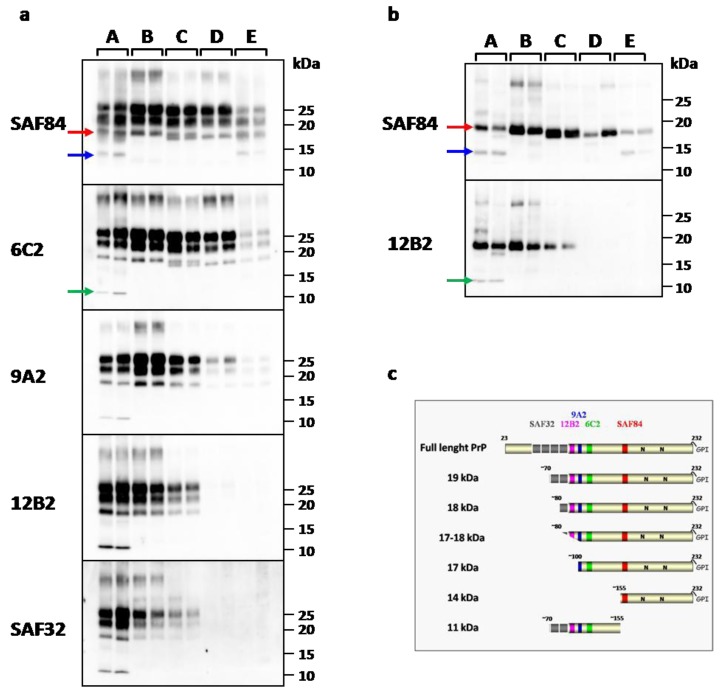

2.2. PrPres-Epitope Mapping

PrPres-epitope mapping was performed on protease treated PrPSc analyzed by western blot with a large panel of mAbs spanning the bank vole PrP, before and after deglycosylation (Figure 1a,b). This sensitive technique allowed the identification of several PrPres fragments which were identified based on the presence or absence of the epitopes examined (Figure 1c). Overall, we identified five different patterns of PrPres, each characterized by the presence of one or more specific PrPres fragments, that were labeled from A to E (Table 1).

Figure 1.

(a) Western Blot analysis of PK resistant PrPSc in representative vole-adapted prion strains. Replica blots were probed with different monoclonal antibodies indicated on the left of each blot. Representative samples for each PrPres type were loaded from the highest (type A) to the lowest (types D and E) MW, as reflected by the progressive loss of N-terminal epitopes. PrPres types are indicated on the top of the blots. Type A (lanes 1-2): CJD type 1; type B (lanes 3-4): sheep scrapie It93 and UK85; type C (lanes 5-6): sCJD MV2; type D (lanes 7-8): BSE; type E (lanes 9-10): sCJD MM2; (b) Samples shown in (a) after deglycosylation. (a,b) Red Arrow: 19 kDa fragment; blue arrow: 14 kDa fragment; green arrow: 11 kDa fragment. (c) Schematic representation of full length PrP and PrPres fragments identified by epitope mapping and deglycosylation. The cleavage sites were determinate by the presence or absence of epitopes examinated (a). The presence of glycosylation sites were confirmed by deglycosylation treatment (b). The location of SAF32, 12B2, 9A2, 6C2, SAF84 mAbs used for the PrPres-epitope mapping are shown.

Table 1.

Classification of prion strains in bank voles based on PrPres analysis.

| Type of PrPres | Strain | Inoculum 1 |

|---|---|---|

| A (19 kDa + 14 kDa + 11 kDa) | CJD type 1 | sCJD MM1 |

| sCJD MV1 | ||

| gCJD E200K | ||

| B (18 kDa) | Scrapie It93 | SS7 |

| B (18 kDa) | Scrapie UK85 | SCR1 |

| SCR10 | ||

| SCR11 | ||

| C (17–18 kDa) | CJD MV2 | sCJD MV2 |

| D (17 kDa) | BSE | BSE |

| E (17 kDa + 14 kDa) | CJD MM2 | sCJD MM2 |

1 MM, MV, or VV indicate genotype at codon 129; 1 or 2 indicate the molecular types, classified according to Parchi et al. [6]

The type A was found only in voles infected with sCJD MM1/MV1 and gCJD E200K, and was characterized by three PrPres fragments of 19, 14 and 11 kDa (Figure 1a,b). The main 19 kDa fragment was detectable equally well by all mAbs, while the 14 kDa fragment was recognized only by SAF84 (Figure 1a,b). Thus 19 kDa and 14 kDa were both C-terminal fragments with a different PK cleavage site at their N-terminus and included the glycosylation sites with the corresponding mono-glycosylated and di-glycosylated bands, resulting in a complex electrophoretic pattern when the membrane was probed with SAF84. In contrast, the 11 kDa fragment was recognized by 6C2, 9A2, 12B2 and SAF32 but not by SAF84, thus indicating that it is an internal fragment cleaved at both the N and C-termini (Figure 1a,b).

The PrPres type B, was found in brain homogenates from bank voles infected with classical scrapie isolates. It was characterized by a single C-terminal fragment of 18 kDa (unglycosylated band): this fragment was recognized by all mAbs, but only partially by SAF32 (Figure 1) indicating that the cleavage site was more C-terminal respect to the type A fragment of 19 kDa.

The type C, characteristic of sCJD MV2 PrPres, showed a molecular weight intermediate between type B and D, which was well detectable with SAF84 and 6C2. With these two antibodies, sometimes the PrPres appeared as a 17–18 kDa doublet (Figure 1a). Type C PrPres was still recognized by mAbs N-terminal to 6C2, although with lower affinity and without showing the PrPres doublet (Figure 1a).

The PrPres type D, found in BSE, was characterized by a single C-terminal fragment of 17 kDa which was well detectable with SAF84 and 6C2, but barely detected by 9A2, and not at all by 12B2 and SAF32 mAbs (Figure 1a,b).

The type E, found only in voles inoculated with sCJD MM2, showed a PrPres characterized by two PK-resistant fragments of 17 and 14 kDa. The main PrPres fragment was a 17 kDa similar to type D, being well recognized only by SAF84 and 6C2. However, compared to type D, it was clearly less glycosylated (Figure 1a). The 14 kDa fragment was C-terminal and glycosylated too, being similar to the 14 kDa PrPres fragment described above in type A PrPres.

Overall, the analysis of PrPres revealed a close correspondence with each strain, allowing us to discriminate all human-derived strains among them and from animal strains (scrapie and BSE). However, voles infected with two different scrapie strains showed identical PrPres patterns.

Interestingly, the PrPres pattern of scrapie, BSE, and sCJD subtypes, seems well preserved after transmission to voles. As previously reported [24], voles infected with sCJD subtypes faithfully reproduced the PrPres electrophoretic mobilities of human counterparts. Also in this study, with more detailed biochemical analyses, we confirmed that vole-adapted sCJD MM1/MV1 had a lower electrophoretic mobility than sCJD MM2 (19 kDa vs. 17 kDa) due to a different N-terminal PK cleavage site. Moreover, additional C-terminal fragments were found to be associated to sCJD subtypes [32,33] as here found in bank voles inoculated with sCJD MM1/MV1 and MM2. In addition, sCJD MV2 adapted to voles showed an intermediate molecular weight between sCJD MV1/MM1 and MM2 and displayed a unique doublet band similar to that described in human sCJD MV2 cases [34]. Furthermore, as observed in natural isolates, in voles the scrapie PrPres was cleaved by PK more N-terminally than PrPres from BSE adapted to vole (18 kDa vs. 17 kDa), as confirmed by differential detection of 12B2 and SAF32 mAbs.

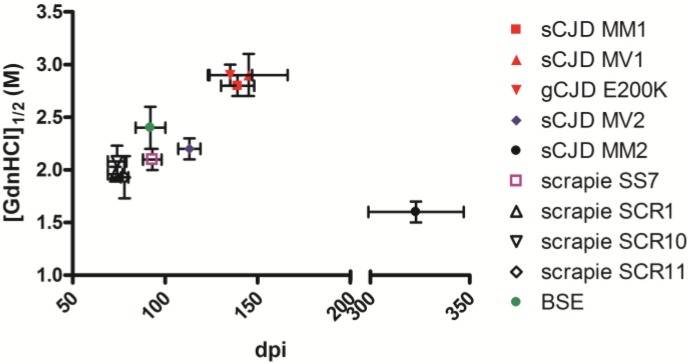

2.3. PrPSc Conformational Stability

As previously reported [11], the conformational stability analysis of PrPSc from voles infected with sCJD and gCJD showed distinct susceptibilities to denaturation. Indeed, sCJD MM1/MV1 and gCJD E200K showed the highest resistance to guanidine with [GdnHCl]1/2 values > 2.8 M while sCJD MM2 was the most susceptible with [GdnHCl]1/2 value of 1.6 M and scrapie (SS7) displayed intermediate susceptibility (2.1 M) [11]. Here we extend these findings by analyzing a further sCJD derived strain, sCJD MV2, a second vole-adapted scrapie strain, called UK85, and BSE (Table 1). PrPSc from voles infected with sCJD MV2 showed intermediate susceptibility to denaturation respect to MV1/MM1/E200K and MM2 CJD, with [GdnHCl]1/2 value of 2.2 ± 0.1 M. PrPSc from voles infected with scrapie UK85 strain showed [GdnHCl]1/2 value of 2.0 ± 0.2 M comparable with that observed from scrapie SS7 strain. The [GdnHCl]1/2 value of BSE PrPSc was 2.4 ± 0.2 M.

Overall, the conformational stability analysis allowed us to discriminate all sCJD subtypes based on their relative susceptibility to denaturation. Moreover, BSE showed a higher resistance to denaturation than scrapie confirming that observed in scrapie and BSE natural isolates [35]. Nevertheless, as observed by PrPres analysis, conformational stability analysis did not enable us to distinguish the two scrapie strains.

Previous studies suggested that the conformational stability of PrPSc aggregates correlated with the incubation time of prion strains, in particular, less stable mice prions replicated more rapidly [36]. On the contrary, a further study reported that short incubation period strains in hamster were characterized by more stable PrPSc [37]. We investigated the relationship between survival times and PrPSc conformational stability in bank vole strains and did not find a clear correlation (Figure 2). If these discrepancies depend on the different animal models used in these studies or on other factors, such as the strain-specific capacity for neuroinvasion [38] and/or neuropathological characteristics [37], will be further investigated.

Figure 2.

Graph of survival times (day post inoculation, dpi) and the conformational stability of PrPSc ([GdnHCl]1/2) of human and animal isolates transmitted to bank voles. Mean survival times ± SD after the third passage were: sCJD MM1, 139 ± 9; sCJD MV1, 145 ± 21; gCJD E200K, 135 ± 12; sCJD MV2, 113 ± 6 (second passage); sCJD MM2, 323 ± 24; scrapie SS7, 93 ± 5; scrapie SCR1, 73 ± 4; scrapie SCR10, 74 ± 5; scrapie SCR11, 78 ± 2 ; BSE, 92 ± 8 [28]. The [GdnHCl]1/2 values (mean ± SD) obtained by CSSA were: sCJD MM1, 2.8 ± 0.1 [11]; sCJD MV1, 2.9 ± 0.2 [11]; gCJD E200K, 2.9 ± 0.1 [11]; sCJD MV2, 2.2 ± 0.1; sCJD MM2, 1.6 ± 0.1 [11]; scrapie SS7, 2.0 ± 0.1 [11]; scrapie SCR1, 2.0 ± 0.1; scrapie SCR10, 2.1 ± 0.1; scrapie SCR11, 1.9 ± 0.2 ; BSE, 2.4 ± 0.2.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Brain Tissues

We selected brain tissues from voles infected with six different vole-adapted prion strains deriving from transmissions of human and animal prions. All tissues analyzed were from vole expressing the PrP variant with met 109 [30]. Brain tissues were derived from second or third vole passages of sCJD MM1 (n = 4), sCJD MV1 (n = 3), sCJD MM2 (n = 5), sCJD MV2 (n = 5), gCJD E200K (n = 3), BSE (n = 5), Italian sheep scrapie SS7 (n = 4) and UK sheep scrapie cases SCR1 (n = 4), SCR10 (n = 4) and SCR11 (n = 6).

3.2. PrPres Analysis

Brain homogenates (20% w/v) were prepared in 100 mM Tris-HCl with Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) at pH 7.4. The homogenates were either used directly or stored at −20 °C. After adding an equal volume of 100 mM Tris-HCl containing 4% sarkosyl, the homogenates were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C with gentle shaking. Proteinase K (Sigma-Aldrich) was added at a final concentration of 250 μg/mL and then the samples were incubated for 1 h at 55 °C with gentle shaking. The reaction was stopped with 3 mM PMSF (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Aliquots of samples were added with an equal volume of isopropanol/butanol (1:1 v/v) and centrifuged at 20,000 g for 5 min. The supernatant were discarded and the pellets were re-suspended in denaturing sample buffer (NuPage LDS Sample Buffer and NuPage Sample Reducing Agent, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and were analyzed by Western Blotting.

Deglycosylation was performed by adding 18 μL of 0.2 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.8% Nonidet P40 (Roche) and 2 μL (80 U/mL) of N-Glycosidase F (Roche) to 5 μL of denaturated samples and by incubating overnight at 37 °C with gentle shaking. Samples were then analyzed by Western blotting.

3.3. Conformational Stability Analysis

As previously described [11], the conformational stability was analysed by CSSA. Briefly, aliquots of brain homogenates (6% w/v in 100 mM TrisHCl, pH 7.4) were added with an equal volume of 100 mM TrisHCl (pH 7.4), sarcosyl 4% and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with gentle shaking. Then, aliquots of each sample were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with different concentrations of GdnHCl (Pierce) to obtain final concentrations ranging from 0 to 4 M. After GdnHCl treatment samples were centrifuged at 20,000 g for 1 h at 22 °C and the pellets were re-suspended in denaturing sample buffer (NuPage LDS Sample Buffer and NuPage Sample Reducing Agent, Invitrogen) and analysed by WB. The dose-response curves allowed us to estimate the concentration of GdnHCl able to solubilize 50% of PrPSc (GdnHCl1/2). Individual denaturation curves were analyzed and best-fitted by plotting the fraction of PrPSc remaining in the pellet as a function of GdnHCl concentration, and using a four parameter logistic equation (GraphPad Prism).

3.4. Western Blotting

Electrophoresis and Western blotting were performed as previously described [24]. Briefly, samples were denatured by adding NuPage LDS Sample Buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, United States) and NuPage Sample Reducing Agent (Invitrogen), and heating for 10 min at 90 °C. After centrifugation at 10,000 g for 5 min each sample was loaded onto 12% bis-Tris polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen). After electrophoresis and Western blotting on PVDF membranes (Immobilon-P; Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA), the blots were processed by SNAP i.d.TM Protein Detection System (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) as described by the manufacturer instructions. The monoclonal antibodies used, their epitopes on bank vole PrP and the working dilutions were as follow: SAF84, PrP residues 163–169, 1.2 μg/mL; 6C2, PrP residues 111–116, 8.6 μg/mL; 9A2, PrP residues 99–101, 1.2 μg/mL; 12B2, PrP residues 89–93, 2.4 μg/mL and SAF32, PrP octarepeat, 2.4 μg/mL.

Following incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA) at 1:13,000, the PrP bands were detected by enhanced chemiluminescent substrate (SuperSignal Femto, Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) and VersaDoc imaging system (Bio-Rad). The chemiluminescence signal was quantified by QuantityOne software (Bio-Rad).

4. Conclusions

This study confirms that by using appropriate biochemical methodologies it is possible to obtain indirect information on the strain-specific conformation of PrPSc, such to allow a strain typing approach with a quite high discriminatory power. Indeed, five out of six prion strains analyzed were characterized by specific PrPSc types, clearly distinguishable by the combined analyses of PrPres fragments and PrPSc conformational stability. As such, our data further support the close relationship between TSE strains and PrPSc properties [4]. However, even within our experimental setting in which tested samples were represented by known, rodent-adapted prion strains, it was not possible to discriminate all prion strains analyzed solely based on the biochemical characterization of PrPSc. Indeed, all vole adapted scrapie isolates showed indistinguishable PrPSc types, although belonging to 2 different vole-adapted scrapie strains, endowed with different survival times (Figure 2) and neuro-pathological phenotypes (data not shown). If this simply reflects our inability to detect conformational differences by an indirect biochemical approaches, or has a broader implication in term of the relationships between PrPSc conformations and prion strains is currently under investigation.

Recently we have applied the biochemical PrPSc typing methods here developed to the study of atypical human and small ruminant prions [39]. Interestingly, we confirmed a very high ability to discriminate PrPSc types, even in prion diseases known to be enriched in PK-sensitive PrPSc aggregates, such as VPSPr and Nor98 [23,39]. Indeed, it was possible not only to discriminate PrPSc types based on the prion disease, but also to associate specific PrPSc types to different PrP mutations in Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker (GSS).

Ongoing studies with other vole-adapted strains and alternative biochemical approaches will hopefully allow to further increase the discriminatory power of PrPSc typing. Although the lack of discrimination of the two scrapie strains, we believe that our study proposes a relatively easy and straightforward biochemical approach useful to refine the biochemical strain typing in animal models and in natural prion isolates.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jan Langeveld for the kind gift of 12B2, 9A2 and 6C2 mAbs.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Prusiner S.B. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science. 1982;216:136–144. doi: 10.1126/science.6801762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruce M.E., Fraser H. Scrapie strain variation and its implications. Curr. Topics Microbiol. Immunol. 1991;172:125–138. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-76540-7_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beringue V., Vilotte J.L., Laude H. Prion agent diversity and species barrier. Vet. Res. 2008;39 doi: 10.1051/vetres:2008024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Telling G.C., Parchi P., DeArmond S.J., Cortelli P., Montagna P., Gabizon R., Mastrianni J., Lugaresi E., Gambetti P., Prusiner S.B. Evidence for the conformation of the pathologic isoform of the prion protein enciphering and propagating prion diversity. Science. 1996;274:2079–2082. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collinge J., Sidle K.C., Meads J., Ironside J., Hill A.F. Molecular analysis of prion strain variation and the aetiology of 'new variant' cjd. Nature. 1996;383:685–690. doi: 10.1038/383685a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parchi P., Castellani R., Capellari S., Ghetti B., Young K., Chen S.G., Farlow M., Dickson D.W., Sima A.A., Trojanowski J.Q., et al. Molecular basis of phenotypic variability in sporadic creutzfeldt-jakob disease. Ann. Neurol. 1996;39:767–778. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bessen R.A., Marsh R.F. Distinct prp properties suggest the molecular basis of strain variation in transmissible mink encephalopathy. J. Virol. 1994;68:7859–7868. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.7859-7868.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kascsak R.J., Rubenstein R., Merz P.A., Carp R.I., Wisniewski H.M., Diringer H. Biochemical differences among scrapie-associated fibrils support the biological diversity of scrapie agents. J. Gen. Virol. 1985;66:1715–1722. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-66-8-1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuczius T., Groschup M.H. Differences in proteinase k resistance and neuronal deposition of abnormal prion proteins characterize bovine spongiform encephalopathy (bse) and scrapie strains. Mol. Med. 1999;5:406–418. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peretz D., Scott M.R., Groth D., Williamson R.A., Burton D.R., Cohen F.E., Prusiner S.B. Strain-specified relative conformational stability of the scrapie prion protein. Protein Sci. 2001;10:854–863. doi: 10.1110/ps.39201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pirisinu L., Di Bari M., Marcon S., Vaccari G., D’Agostino C., Fazzi P., Esposito E., Galeno R., Langeveld J., Agrimi U., et al. A new method for the characterization of strain-specific conformational stability of protease-sensitive and protease-resistant prp. PloS One. 2010;5:e12723. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Safar J., Wille H., Itri V., Groth D., Serban H., Torchia M., Cohen F.E., Prusiner S.B. Eight prion strains have prp(sc) molecules with different conformations. Nat. Med. 1998;4:1157–1165. doi: 10.1038/2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stack M.J., Chaplin M.J., Clark J. Differentiation of prion protein glycoforms from naturally occurring sheep scrapie, sheep-passaged scrapie strains (ch1641 and ssbp1), bovine spongiform encephalopathy (bse) cases and romney and cheviot breed sheep experimentally inoculated with bse using two monoclonal antibodies. Acta Neuropathol. 2002;104:279–286. doi: 10.1007/s00401-002-0556-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stack M., Jeffrey M., Gubbins S., Grimmer S., Gonzalez L., Martin S., Chaplin M., Webb P., Simmons M., Spencer Y., et al. Monitoring for bovine spongiform encephalopathy in sheep in great britain, 1998–2004. J. Gen. Virol. 2006;87:2099–2107. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81254-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vulin J., Biacabe A.G., Cazeau G., Calavas D., Baron T. Molecular typing of protease-resistant prion protein in transmissible spongiform encephalopathies of small ruminants, france, 2002–2009. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011;17:55–63. doi: 10.3201/eid1701.100891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hope J., Wood S.C., Birkett C.R., Chong A., Bruce M.E., Cairns D., Goldmann W., Hunter N., Bostock C.J. Molecular analysis of ovine prion protein identifies similarities between bse and an experimental isolate of natural scrapie, ch1641. J. Gen. Virol. 1999;80:1–4. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hill A.F., Sidle K.C., Joiner S., Keyes P., Martin T.C., Dawson M., Collinge J. Molecular screening of sheep for bovine spongiform encephalopathy. Neurosci. Lett. 1998;255:159–162. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(98)00736-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saa P., Sferrazza G.F., Ottenberg G., Oelschlegel A.M., Dorsey K., Lasmezas C.I. Strain-specific role of rnas in prion replication. J. Virol. 2012;86:10494–10504. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01286-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tzaban S., Friedlander G., Schonberger O., Horonchik L., Yedidia Y., Shaked G., Gabizon R., Taraboulos A. Protease-sensitive scrapie prion protein in aggregates of heterogeneous sizes. Biochemistry. 2002;41:12868–12875. doi: 10.1021/bi025958g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pastrana M.A., Sajnani G., Onisko B., Castilla J., Morales R., Soto C., Requena J.R. Isolation and characterization of a proteinase k-sensitive prpsc fraction. Biochemistry. 2006;45:15710–15717. doi: 10.1021/bi0615442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thackray A.M., Hopkins L., Bujdoso R. Proteinase k-sensitive disease-associated ovine prion protein revealed by conformation-dependent immunoassay. Biochem. J. 2007;401:475–483. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cronier S., Gros N., Tattum M.H., Jackson G.S., Clarke A.R., Collinge J., Wadsworth J.D. Detection and characterization of proteinase k-sensitive disease-related prion protein with thermolysin. Biochem. J. 2008;416:297–305. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gambetti P., Dong Z., Yuan J., Xiao X., Zheng M., Alshekhlee A., Castellani R., Cohen M., Barria M.A., Gonzalez-Romero D., et al. A novel human disease with abnormal prion protein sensitive to protease. Ann. Neurol. 2008;63:697–708. doi: 10.1002/ana.21420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nonno R., Di Bari M.A., Cardone F., Vaccari G., Fazzi P., Dell’Omo G., Cartoni C., Ingrosso L., Boyle A., Galeno R., et al. Efficient transmission and characterization of creutzfeldt-jakob disease strains in bank voles. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e12. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zanusso G., Polo A., Farinazzo A., Nonno R., Cardone F., Di Bari M., Ferrari S., Principe S., Gelati M., Fasoli E., et al. Novel prion protein conformation and glycotype in creutzfeldt-jakob disease. Arch. Neurol. 2007;64:595–599. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.4.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Bari M.A., Chianini F., Vaccari G., Esposito E., Conte M., Eaton S.L., Hamilton S., Finlayson J., Steele P.J., Dagleish M.P., et al. The bank vole (myodes glareolus) as a sensitive bioassay for sheep scrapie. J. Gen. Virol. 2008;89:2975–2985. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/005520-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piening N., Nonno R., Di Bari M., Walter S., Windl O., Agrimi U., Kretzschmar H.A., Bertsch U. Conversion efficiency of bank vole prion protein in vitro is determined by residues 155 and 170, but does not correlate with the high susceptibility of bank voles to sheep scrapie in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:9373–9384. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512239200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agrimi U., Nonno R., Dell’Omo G., Di Bari M.A., Conte M., Chiappini B., Esposito E., Di Guardo G., Windl O., Vaccari G., et al. Prion protein amino acid determinants of differential susceptibility and molecular feature of prion strains in mice and voles. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000113. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Di Bari M.A., Nonno R., Castilla J., D'Agostino C., Pirisinu L., Riccardi G., Conte M., Richt J., Kunkle R., Langeveld J., Vaccari G., Agrimi U. Chronic wasting disease in bank voles: Characterisation of the shortest incubation time model for prion diseases. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003219. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cartoni C., Schinina M.E., Maras B., Nonno R., Vaccari G., Di Bari M., Conte M., de Pascalis A., Principe S., Cardone F., et al. Quantitative profiling of the pathological prion protein allotypes in bank voles by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B. 2007;849:302–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bruce M.E., Boyle A., Cousens S., McConnell I., Foster J., Goldmann W., Fraser H. Strain characterization of natural sheep scrapie and comparison with bse. J. Gen. Virol. 2002;83:695–704. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-3-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Notari S., Strammiello R., Capellari S., Giese A., Cescatti M., Grassi J., Ghetti B., Langeveld J.P., Zou W.Q., Gambetti P., et al. Characterization of truncated forms of abnormal prion protein in creutzfeldt-jakob disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:30557–30565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801877200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zou W.Q., Capellari S., Parchi P., Sy M.S., Gambetti P., Chen S.G. Identification of novel proteinase k-resistant c-terminal fragments of prp in creutzfeldt-jakob disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:40429–40436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308550200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Notari S., Capellari S., Giese A., Westner I., Baruzzi A., Ghetti B., Gambetti P., Kretzschmar H.A., Parchi P. Effects of different experimental conditions on the prpsc core generated by protease digestion: Implications for strain typing and molecular classification of cjd. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:16797–16804. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313220200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pirisinu L., Migliore S., Di Bari M.A., Esposito E., Baron T., D’Agostino C., De Grossi L., Vaccari G., Agrimi U., Nonno R. Molecular discrimination of sheep bovine spongiform encephalopathy from scrapie. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011;17:695–698. doi: 10.3201/eid1704.101215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Legname G., Nguyen H.O., Peretz D., Cohen F.E., DeArmond S.J., Prusiner S.B. Continuum of prion protein structures enciphers a multitude of prion isolate-specified phenotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:19105–19110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608970103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ayers J.I., Schutt C.R., Shikiya R.A., Aguzzi A., Kincaid A.E., Bartz J.C. The strain-encoded relationship between prp replication, stability and processing in neurons is predictive of the incubation period of disease. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1001317. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bett C., Joshi-Barr S., Lucero M., Trejo M., Liberski P., Kelly J.W., Masliah E., Sigurdson C.J. Biochemical properties of highly neuroinvasive prion strains. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002522. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pirisinu L., Nonno R., Esposito E., Benestad S.L., Gambetti P., Agrimi U., Zou W.Q. Small ruminant Nor98 prions share biochemical features with human Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker disease and variably protease-sensitive prionopathy. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66405. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]