Sickle-cell disease (SCD) is a genetic blood disorder characterized by red blood cells that assume an abnormal, rigid, sickle shape. Sickling decreases the cells’ flexibility and results in the risk of various complications. It is a serious disease. In the United States, the average life expectancy of people with this condition is estimated to be 42 years for males and 48 years for females.1

In the US, SCD is usually detected at birth through newborn screening. Children diagnosed with the disease need to be closely monitored by a pediatrician and must take penicillin daily until they are around five years old to ward off early the childhood illnesses their immune systems can have increased difficulty fighting.

These children will need to be under a doctor's care for their entire lives. As they grow older, they must take more control of their own healthcare— and that's tough. By the age of about 14, children with SCD need to prepare for the transition from the comprehensive care they have received at the pediatric hospital to the reality of a potentially less-integrated adult hospital or clinic. This transition occurs at a time when many of them are making other life changes (for example, going to college, getting a job, starting a family). In addition, for some patients the disease is also worsening. SCD patients between the ages of 18 and 30 tend to have higher than average hospital readmission and acute care utilization rates, as well as increased mortality.2 The question is: How can the transition process be managed for these patients so that they feel prepared for an adult clinic and are able to manage their disease in a real-world setting without feeling abandoned or confused?

The Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) is grappling with this problem. To solve it, they joined forces with the Live Well Collaborative (LWC), a nonprofit founded in 2007 by the University of Cincinnati (UC) and Procter & Gamble to focus on research and product and service development for the underserved 50-plus marketplace. Working with CCHMC on this project would allow the LWC to expand its capabilities to developing products and services for living better across the lifespan. The Collaborative, working with UC, a major research university, taps the talent of the top-ranked colleges of design, architecture, art, and planning (DAAP), business, engineering, nursing, and medicine, among others, to do project studios. Interdisciplinary teams of UC faculty and students use a 12-week design-thinking model to translate consumer research into products and services.

The purpose of this project was to develop patient-oriented solutions to enhance the transition from pediatric to adult care. Could the two organizations partner in an integrated way to achieve the desired outcomes of developing a solution that will empower young people to manage their own healthcare and of teaching CCHMC staff to integrate design methods into their everyday healthcare approach?

The project

The SCD project took the form of an eight-week summer studio—a limited timeframe for such a complicated problem. However, LWC fortunately has a structured research process model that the team believed would help them make significant progress over such a short time period. The studio involved weekly meetings at the LWC, interviews and observations at CCHMC, and co-creation sessions with patients and providers at CCHMC. The core interdisciplinary research team included a partnership consisting of four DAAP students from graphic, digital, and industrial design, completing placements at LWC; two DAAP faculty supervisors from LWC; and a psychologist, psychology fellow, and three to five psychology research assistants from CCHMC. The provider co-creation sessions were held with members of the multidisciplinary SCD Transition Team (that is, hematologists, nurse practitioners, nurse care managers, social workers, and school intervention staff). The patient co-creation sessions were held with seven to eight patients aged 16 to 24 years.

LWC's approach is based on design thinking, which in this context involves using design methods to develop technologically feasible and cost-effective solutions that meet people's needs.3 For LWC, this encompasses prototyping solutions early in the research process and then testing them through an iterative process via co-creation sessions with consumers who help to validate and refine concepts. The LWC studio process is divided into four phases: research, ideation, validation, and refinement.

The research phase relies heavily on a team approach. For this project, the LWC team began by immersing themselves in an intense review of literature on sickle cell disease itself, the medical challenges this population faces, and barriers to transition. Once they had become knowledgeable about SCD, they conducted a stakeholder analysis. The stakeholders in this case were eight patients. Patients had a mean age of 19, and 60 percent were male. Two LWC students and one psychology research assistant or fellow accompanied some of these patients to their appointments at the pediatric and adult clinics, asking questions and observing their interactions with care providers. (One of the unique benefits of having a student-based research team is the personal level of peer-to-peer interaction with patients. Instead of enduring what would be in effect a formal interview between strangers, the patients shared personal experiences that their young counterparts could understand and identify with.) Next, they synthesized the research and used “mind map” diagrams to display common themes discovered in the literature and stakeholder analysis. One discovery was that SCD varies and manifests differently in each patient. For example, some patients often had pain; others did not. Some patients had many complications from SCD; others had few. In addition, the level of support received from the medical team and from the family varied. Some patients were able to actively solve problems related to managing their illness (such as self-management and the social aspects of having SCD), while others were not. During this phase, the LWC also developed profiles for each patient interviewed and outlined the steps of the transition process. The advantage of using design researchers for this research synthesis is that they can develop user-friendly materials that visually communicate a large amount of information.

The goal of the ideation phase was to use the maps and profiles to identify insights across patients and begin to identify process opportunity areas. During this phase, LWC and CCHMC teams used a co-invention approach to develop ways to improve the transition process. Three main concepts emerged: 1) the transition process should be standardized but flexible enough to meet individual patient needs; 2) patients and providers need a shared vision around transition and a way to communicate throughout the process; and 3) patients need a way to tie transition goals to more-general developmental milestones, as they generally did not see the connection between healthcare management tasks (for example, scheduling medical appointments) and other life tasks (for example, scheduling meetings at work/school). Using these concepts, the LWC team members created visual representations of possible alternatives that were validated and refined with patients and providers.

The purpose of the validation and refinement phase is to test and further improve concepts. Visual concepts were simplified, clarified, and validated during co-creation sessions. During these sessions, patients and providers were asked if the concepts accurately reflected their experience and would be useful, and if they could be improved or changed in any way. The LWC team then did several rounds of validation and refinement to determine final concept direction.

The tools

Patient profiles

The team created individualized patient profiles that served as an information summary of the key domains affecting the transition to adult care: the patient's daily life, self-management skills, attitudes toward transitioning, relationship with care providers, and future goals. The profiles also provide infographics about how SCD affects that individual's body, his or her pain experience, and management strategies. The SCD clinical team and patients found these profiles to be useful because they: 1) concisely provided relevant information about where patients were with respect to the key domains affecting transition; 2) could serve as a self-management tool and help patients and providers understand the impact of SCD on an individual patient quickly (at a glance); 3) identify areas where the team could provide more support or education to enhance self-management and transition readiness; and 4) allow for comparisons across patients with respect to pain experience, management strategies, and level of support. The core research team and the clinical team envision these profiles as a tool that patients can create and customize themselves, and also as an aid for helping patients learn about how SCD affects their individual bodies.

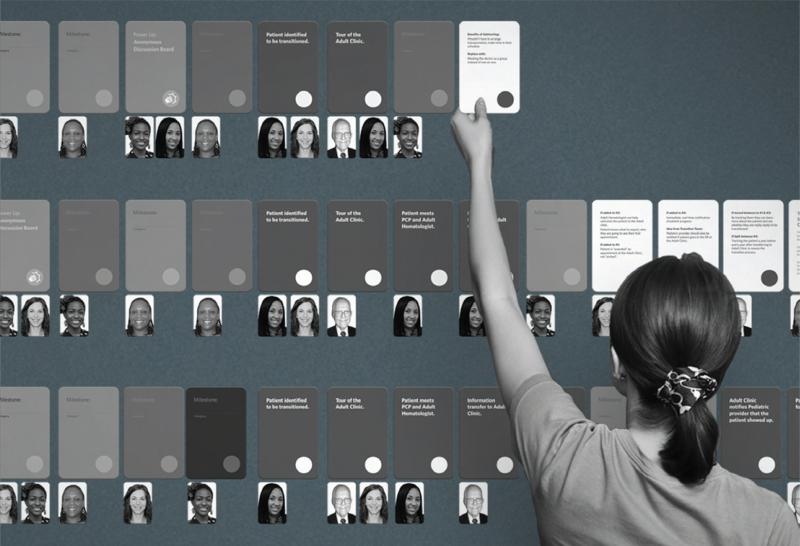

Transition Step, Milestone, and Power-Up cards

The LWC team also designed and created a card series to help facilitate the transition process. Transition Step cards represent the sequence of events patients have to go through before they can transfer to adult care. Care providers can arrange the deck of cards to design and visualize a personalized transition process for each patient. A set of cards would include steps such as: patient identified to be transitioned, tour of the adult clinic, patient meets PCP and adult hematologist, information transfer to the adult clinic, and so on.

Milestone cards incorporate patients’ motivations and individual needs into the transition process. They represent goals in different areas of the patient's life and show the activities patients must perform in order to achieve those goals. For example, a patient struggling with self-management skills may be given the milestone goal of “getting to an appointment on my own.” The patient's missions or tasks might include calling and scheduling his or her own appointment, planning transportation, and talking to the healthcare provider without a parent or other adult present at the appointment.

Power-Up cards play an important role in defining the amount of intervention needed for a patient. The LWC team wanted a way for the hospital staff not only to visualize progress, but also to recognize when there is a need for more intense intervention. That intervention might be anything from utilizing resources already available at the hospital—such as self-management classes—to resources for parents, such as an education toolkit for helping their teen manage his or her SCD.

Patient-Provider Interface

The team also developed a prototype of a journal that would serve as a patient-provider interface. The journal could be a physical binder or a digital website that patients would use to keep track of where they were with respect to learning the skills they needed to transition to the adult care system. This journal would also allow providers to give patients feedback on their achievements. Within these journals, patients could keep important things, such as insurance cards and information about their medications. The journal would also contain a space for each milestone card (mentioned in the previous section), which is then broken down into individual missions the patient is encouraged to accomplish (for example, explaining one's illness to a peer before the next clinic visit). Completing a series of missions results in the patient first earning the reward of visually seeing his or her personal progress and growth, and secondly in material gifts such as iTunes gift cards and other tangible incentives.

Next steps

The collaboration between the LWC and CCHMC teams will continue as the patient tools move forward through pilot testing, validation, and implementation, with the long-term goal of integrating them into the transition process. Patients are in the process of evaluating an interactive web-based mock-up of their profiles, looking eventually to use them as a self-management and communication tool to personalize and then print, download to a mobile phone, or email to a healthcare provider. The SCD clinical team is also evaluating a web-based patient-provider interface that would allow them to track and monitor patient completion of transition-related developmental milestones. This interface would also allow them to monitor important health outcomes (for example, healthcare utilization and health-related quality of life).

The research process is an example of how design thinking can contribute to intervention and tool development within the field of healthcare. It is also important to identify and understand how funding sources through the healthcare grant system can fund faculty and student support to continue this work.

FIGURE 1.

A series of cards to help both patients and providers keep track of where they are in the transition process.

FIGURE 2.

Biography

Lori E. Crosby, PsyD, is a pediatric psychologist at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center. She is also co-director of Innovations in Community Research and Program Evaluation and the director of training for the Community Engagement Core of the Cincinnati Center for Clinical and Translational Science and Training. As a director and collaborator on more than 15 federal grants, Crosby has emerged as a leader in conducting research to transform the healthcare system for adolescents and young adults with sickle cell disease. In 2012, she was elected as Fellow of the American Psychological Association Division 54 for her work with individuals affected by sickle cell disease. She holds a doctorate from Wright State University School of Professional Psychology (Dayton, Ohio).

Lori E. Crosby, PsyD, is a pediatric psychologist at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center. She is also co-director of Innovations in Community Research and Program Evaluation and the director of training for the Community Engagement Core of the Cincinnati Center for Clinical and Translational Science and Training. As a director and collaborator on more than 15 federal grants, Crosby has emerged as a leader in conducting research to transform the healthcare system for adolescents and young adults with sickle cell disease. In 2012, she was elected as Fellow of the American Psychological Association Division 54 for her work with individuals affected by sickle cell disease. She holds a doctorate from Wright State University School of Professional Psychology (Dayton, Ohio).

P:(513)636-5380 F: (513)636-7400 lori.crosby@cchmc.org

Naomi E. Joffe, PhD, holds a doctorate in clinical psychology and completed her residency and fellowship in pediatric psychology at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC). Joffe stayed on at CCHMC and is now clinical faculty within the Division of Behavioral Medicine serving hematology patients within the Cancer and Blood Diseases Institute. Her research focuses on diverse pediatric populations within the context of chronic illness, and she has examined factors related to adherence, self-management, pain, and coping. She earned her bachelor's degree from Indiana University and her doctorate from Georgia State University.

Naomi E. Joffe, PhD, holds a doctorate in clinical psychology and completed her residency and fellowship in pediatric psychology at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC). Joffe stayed on at CCHMC and is now clinical faculty within the Division of Behavioral Medicine serving hematology patients within the Cancer and Blood Diseases Institute. Her research focuses on diverse pediatric populations within the context of chronic illness, and she has examined factors related to adherence, self-management, pain, and coping. She earned her bachelor's degree from Indiana University and her doctorate from Georgia State University.

P: (513)803-5161 F: (513)803-0415 naomi.joffe@cchmc.org

Linda A. Dunseath is currently executive director of the Live Well Collaborative (LWC), an innovation incubator that partners with the University of Cincinnati (UC) and member organizations to develop products and services to meet the growing needs of the 50+ population. Since joining LWC in 2007, she has worked with industry partners and UC to plan 37 projects that have exposed more than 500 students and 30 faculty to multidisciplinary teamwork using design-thinking tools. She holds a BS in business (marketing) from Miami University.

Linda A. Dunseath is currently executive director of the Live Well Collaborative (LWC), an innovation incubator that partners with the University of Cincinnati (UC) and member organizations to develop products and services to meet the growing needs of the 50+ population. Since joining LWC in 2007, she has worked with industry partners and UC to plan 37 projects that have exposed more than 500 students and 30 faculty to multidisciplinary teamwork using design-thinking tools. She holds a BS in business (marketing) from Miami University.

P: (513)558-7348 ldunseath@livewellcollaborative.org

Rachel Lee is a graphic communication design student at the College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning at the University of Cincinnati. She has participated in two cooperative education semesters at Live Well Collaborative. This summer she will continue her cooperative education at THRIVE Consulting LLC, a design and innovation consultancy in Atlanta.

Rachel Lee is a graphic communication design student at the College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning at the University of Cincinnati. She has participated in two cooperative education semesters at Live Well Collaborative. This summer she will continue her cooperative education at THRIVE Consulting LLC, a design and innovation consultancy in Atlanta.

P: (513)558-7348 rachellee@livewellcollaborative.org

Notes

- 1.Platt OS, Brambilla DJ, Rosse WF, et al. Mortality in Sickle Cell Disease: Life Expectancy and Risk Factors for Early Death. New England Journal of Medicine. 330(1994):1639–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406093302303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hassell K. Population Estimates of Sickle Cell Disease in the U.S. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 38(4):S512–21. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hunt SE, Sharma N. Transition from Pediatric to Adult Care for Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. Journal of the American Medical Association. 304(4):408–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown Tim. Change by Design. HarperCollins e-books; 2009. [Google Scholar]