Abstract

Robotic assisted hysterectomy with regional lymphadenectomy is increasingly used for the treatment of endometrial carcinoma. In the present study we evaluated the feasibility and technique of robotic assisted hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy in patients with endometrial carcinoma. A prospective randomized study was undertaken from July 2011 to June 2012, in 50 consecutive patients with carcinoma endometrium. Demographic (age, BMI) and perioperative data (operating time, estimated blood loss, total number of lymph nodes retrieved, hospital stay, conversion to open procedure, intraoperative and postoperative complications) of robotic assisted surgery were compared with open staging procedure. Mean age of the patient and BMI in both groups were comparable with no significant difference. Estimated blood loss (81.28 ml), hospital stay (1.94 days) and perioperative complications were significantly less in robotic assisted group in comparison to open method. Mean number of lymph nodes removed were 30.56 versus 27.6 which is suggestive of significant difference statistically. Operative time decreased as the experience of the surgeon increased but still significantly remained higher than the open procedure after 25 robotic assisted surgeries. All robotic surgeries were completed successfully without converting to open method. Robotic assisted staging procedure for endometrial carcinoma is feasible without converting to open method, with the advantages of decreased blood loss, short duration of hospital stay and less postoperative minor complications. Operative time will decrease further as the experience of surgeon increases. Para-aortic lymph node dissection is easily done and with a better ergonomics for surgeon.

Keywords: Robotic assisted surgery, Staging laparotomy, Endometrial cancer, Hysterectomy

Introduction

Carcinoma endometrium is one among the common cancers in females across India. Endometrial cancer is surgically staged disease as per FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) guidelines. Surgical management is the mainstay of initial treatment for majority of patients and comprehensive surgical staging guides in the risk stratification and planning of postoperative adjuvant therapy. Minimally invasive surgery has gained acceptance for the surgical treatment of endometrial cancer because, compared with laparotomy, it is associated with fewer complications, shorter hospitalization, and faster recovery [1–4]. Adoption of laparoscopic surgery for treatment of endometrial cancer has been slow, primarily because of the steep learning curve and limitations in obese patients [5], more so when extended para-aortic lymph node dissection is indicated in high risk patients.

The benefits of robotic surgery as a minimally invasive surgical technique parallel those of traditional laparoscopy, with the added advantages of overcoming several barriers to the use of laparoscopy, such as limitations of the human hand (seven degrees of movement and elimination of hand tremors), elimination of the fulcrum effect of laparoscopy (the robotic arms imitate the movements of the surgeon’s hand), improved visualization (three-dimensional stereoscopic imaging), and increased independence of the operating surgeon, thus enabling the robotic-assisted management of gynecologic malignancies to become more widely utilized. It has advantages of multi-tasking endowrist instrumentation, stability of camera with better ergonomics for operating surgeon. In the present study we evaluated the feasibility and technique of robotic assisted hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy in patients with endometrial carcinoma in the present Indian population.

Patients and Methods

A prospective randomized study was undertaken from July 2011 to June 2012 in Manipal Comprehensive Cancer Center, Bangalore. Fifty consecutive patients were alternatively allotted between the robotic assisted surgery with da Vinci surgical S system (Intuitive Surgical®, Sunnydale, CA) and traditional laparotomy arm. Twenty five patients of endometrial carcinoma who underwent robotic assisted panhysterectomy and regional lymphadenectomy were compared with similar open procedure in 25 patients. Technique and feasibility of robotic-assisted surgery in terms of operating time, estimated blood loss, total number of lymph nodes retrieved, hospital stay, conversion to open procedure, intraoperative and postoperative complications were analyzed. Operative time was defined as the time from incision to closure, which includes docking time in robotic surgery. Estimated blood loss was based on operative and anesthesiologist notes. Lymph node removal was the number of lymph nodes at pathologic analysis. Hospital stay was from admission to discharge. Intraoperative complications were defined as bowel, bladder, ureteral, nerve or vascular injury during surgery. Postoperative complications were categorized into major and minor complications. Major complications included vaginal cuff dehiscence, cuff cellulitis or pelvic abscess, deep-vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolus, myocardial infarction, and bacteremia. Minor complications included urinary tract infection, wound infection, and ileus. Ethical committee approval was taken for the study.

Preoperative Preparation

Patient takes clear liquids a day prior to surgery. Night before the surgery proctoclysis enema and two dulcolax (bisacodyl) tablets are given per oral. We do not administer peglec which causes dilatation of bowel.

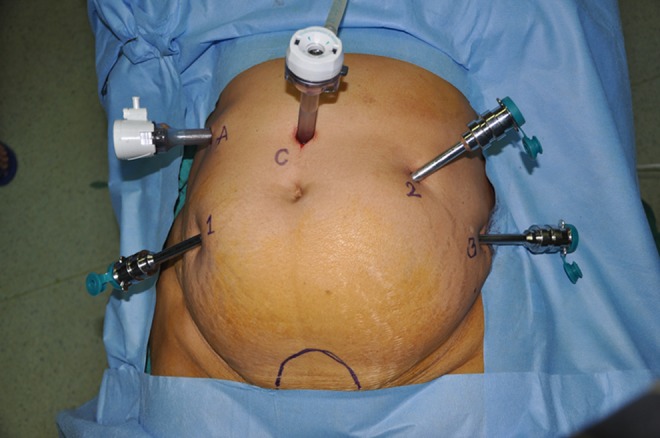

Port Placement (Fig. 1) and Instrumentation (Fig. 2)

Fig. 1.

Port placement (1- Arm one, 2- Arm two, 3- Arm three, C- Camera, A- Assistant)

Fig. 2.

Instruments used (Arm 1- Hot shear (scissors), Arm 2 - Bipolar, Arm 3 - Prograsper)

V-CARE (Vaginal – Cervical Ahluwalia Retractor - Elevator) uterine manipulator (ConMed endosurgery, Utica, NY) is used to manipulate the uterus intraoperatively. A 12 mm camera port is placed 3 cm above the umbilicus in the midline with optical trocar. Rest of the ports are placed after insufflating the abdomen with gas and marking the port measurements. Arm one (8 mm) port is placed on patient’s right side, 3–5 cm below and atleast 8 cm lateral to camera port. Arm two (8 mm) port is placed on patient’s left side, 8 cm lateral and 3–5 cm below the level of the camera port. Third arm (8 mm) is placed on patient’s left side, 2 cm above anterior superior iliac spine and 8 cm away from the second port. daVinci S robot is used with central docking. Assistant port (12 mm) is placed on patient’s right side, slightly cephalad to the camera port on an arc at the midpoint between the camera port and the instrument arm one port.

Zero degree scope is used for all the steps, except for para-aortic lymph node dissection where 30° down scope is used. In arm one hot shears (monopolar curved scissors), in arm two fenestrated bipolar forceps and in arm three prograsp forceps is used.

Surgical Steps

Dissection is done in a circular fashion from one round ligament to the other.

-

Step 1

Uterus is retracted to the patient’s left side with the help of uterine manipulator and third arm of robot. Dissection starts with incising the peritoneum over infundibulopelvic triangle, isolating the ureter and ovarian pedicle. Then round ligament is transected near inguinal ring with hot shear (monopolar diathermy). Incision is extended anteriorly into anterior leaf of broad ligament up to lateral utero-vesical junction. Coagulate and transect right uterine pedicle and cardinal ligament. Pay careful attention to the course of the ureter.

-

Step 2

Urinary bladder is lifted up with 3rd arm and uterus is retroverted with the help of uterine manipulator and 2nd arm. Vesico-uterine groove identified and bladder is dissected away from the uterus and adhesions if any are dissected with the cold knife (hot shear).

-

Step 3

Left side isolation of ureter and dissection of round ligament is done similar to step one. Both side ovarian pedicles are coagulated with bipolar diathermy but not divided until complete dissection is done.

-

Step 4

Posterior part dissection is done by separating rectum from the uterus with the division of uterosacral ligaments on either side. The course of the ureter must be noted during this step.

-

Step 5

Anterior and posterior colpotomies are done by incising over the colpotomy ring. Finally both the ovarian pedicles are divided. Specimen is delivered through vagina by pulling out uterine manipulator and abdominal pneumatic pressure is maintained by packing the vagina with an adequate size ball made of mop inside a surgical hand glove.

-

Step 6

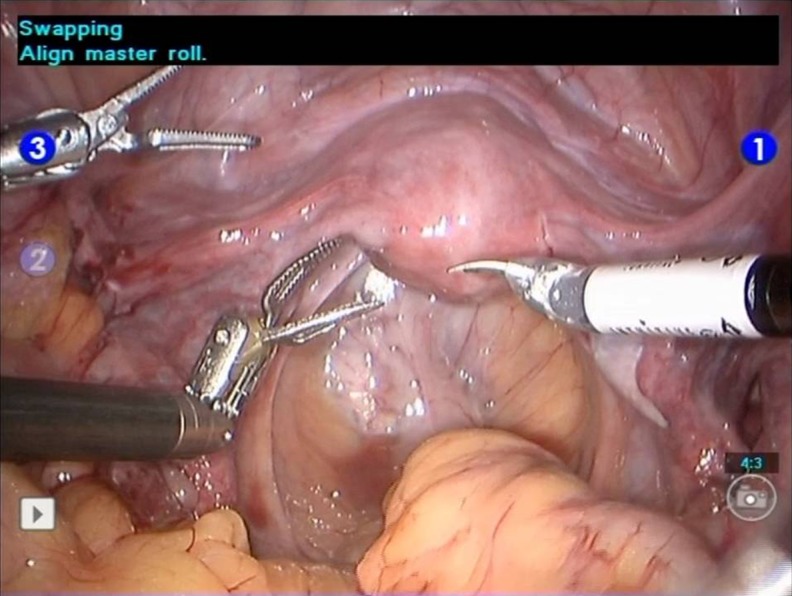

(Figs. 3, 4, 5) Bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy is done by exposing para-rectal and para-vesical spaces. Separate specimen bag is used for each side lymph nodes and specimen is delivered through vagina. Para-aortic lymph node dissection is done when indicated. Vaginal cuff is closed with a 15 cm long self retaining polydioxanone (monofilament, violet) barb suture and uterosacral ligaments are included laterally.

Fig. 3.

Distal limit of pelvic dissection

Fig. 4.

Proximal limit of pelvic dissection

Fig. 5.

Obturator triangle clearance in pelvic dissection

Statistical Analysis

Mean values in each variable are compared and p value is obtained by using the student t test (unpaired). The Statistical software namely SAS 9.2, SPSS 15.0, Stata 10.1, MedCalc 9.0.1, Systat 12.0 and R environment ver.2.11.1 were used for the analysis of the data.

Results

Total 25 patients of robotic surgery were compared with 25 open surgeries. During dissection, identifying and safeguarding ureter is the first step. Ovarian pedicles are taken at the end of hysterectomy in order to keep the uterus in its anatomical orientation and prevent rotation.

Mean age of the patient and BMI in both groups were comparable with no significant difference (Table 1). Operative time for robotic-assisted hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy was significantly more in first five cases and gradually reduced with a mean of 177.5 min in subsequent 10 cases and 142.5 min in next 10 cases. Operative time for open surgery remained same throughout the series. Estimated blood loss was significantly less with robotic-assisted surgery (81.28 ml) compared to open method (234 ml). Number of lymph nodes removed by robotic method (30.56) was equal or higher than the open method (27.6) which is suggestive of significant difference. Length of hospital stay was significantly shorter in robotic-assisted arm (1.94 versus 5.54 days). One patient in the robotic arm had minor external iliac vein injury while doing pelvic lymph node dissection, which was controlled with prolene sutures, without converting to open method. None of the patients in open method had any intraoperative complications with no significant difference from robotic assisted arm. There were no major or minor postoperative complications observed in robotic-assisted surgery. In the open method, three patients had paralytic ileus, one had seroma collection in the wound and one had urinary tract infection which statistically has moderate significance. Paralytic ileus was seen especially when extensive para-aortic lymph node dissection is done. There were no major complications in open method. None of the robotic-assisted surgeries were converted to open method because of complications or technical difficulty.

Table 1.

Analysis of demographic and operative data

| Variable | Robotic surgery | Open surgery | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs | 51.44 | 53 | 0.422 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.96 | 31.88 | 0.413 |

| Operating time, min | 245 in first 5 cases 177.5 in next 10 cases 142.5 in next 10 cases |

126 124 117 |

< 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 |

| Estimated blood loss, mL | 81.28 | 234 | < 0.001 |

| Number of lymph nodes removed | 30.56 | 27.6 | 0.071 |

| Hospital stay, days | 1.94 | 5.54 | < 0.001 |

| Intraoperative complications | 1 | 0 | 1.000 |

| Postoperative complications (minor) | 0 | 5 | 0.050 |

| Postoperative complications (major) | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

Para-aortic lymph node dissection up to renal vessels was done in 8 patients from robotic arm and median lymph node yield was 8.4, which was similar to open arm (9 lymph nodes) with no significant difference.

Discussion

Surgical staging for endometrial cancer is considered the standard of care. Since the approval of robotic gynecologic surgery by FDA in 2005, many surgeons have switched over to robotic approach. In India, few centers have started this minimally invasive method and the early experience is evolving. The robotic instrumentation can move with seven degrees of freedom simulating the movement of the human wrist, and hence are sometimes referred to as “wristed” instruments. The visual quality of the current robotic system is superior to that of conventional laparoscopy. As a result a three-dimensional view is created leading to enhanced depth perception. The view can also be highly magnified depending on how close the surgeon drives the camera to the area of interest. As a result of greatly improved dexterity and vision, a greater precision in surgery can be achieved than the traditional laparoscopy, facilitating the performance of more complex procedures and thus reducing the learning curve. Many of the limitations of laparoscopy are overcome by the robotics platform. The three-dimensional, magnified images combined with wristed instrumentation, tremor filtration and motion scaling allow the surgeon to recapitulate open surgery.

In the preoperative preparation bisacodyl tablets and proctoclysis enema is used the night before surgery to empty the bowel. We found in our earlier series before starting this study, that using peglec solution to clean the intestine causes bowel dilatation which interferes with the adequate visibility during the surgery. V-CARE is used for manipulation of uterus. It saves OR (operating room) time, displaces cervix away from ureters, displaces bladder anteriorly, reduces blood loss, defines dissecting plane of colpotomy, prevents loss of pneumoperitoneum [6].

We found it very comfortable. Myoma screw cannot be used as it violates the basic principles of oncology in endometrial cancer. On the right hand (arm one) we use hot shears as it can be used as cold knife and also monopolar diathermy. Cold knife dissection helps in separating urinary bladder from the uterus without undue damage to the bladder. Most of the dissection is done by hot shears with the help of fenestrated forceps. Arm two fenestrated bipolar forceps has adequate length to coagulate ovarian and uterine pedicles. It is also a sturdy instrument which can hold the needle firmly while suturing the vaginal cuff. We can save the cost of using one extra needle driver. Some surgeons use Maryland forceps in arm two, but we found it to be shorter in length to encompass the vascular pedicles and cannot grasp the needle while suturing the vaginal cuff. Prograsp forceps in arm three is used to lift the bladder while creating uterovesical plane and to hold the left end of vagina while suturing the vaginal cuff. It is also useful in vessel retraction during lymphadenectomy., especially in obturator fossa. This port has tendency to slip out and we advise to place it far more inside than the remaining ports.

Endometrial cancer is particularly suited for robotic surgery for several reasons. The majority of women with endometrial cancers are obese and at greater risk for postoperative wound complications, and would benefit from a minimally invasive procedure with smaller incisions, resulting in less risk for wound problems. It has profound advantage in high risk endometrial cancer patients where extended para-aortic lymph node dissection is indicated. In a retrospective comparison of obese women and morbidly obese women undergoing traditional laparoscopic approach versus robotic-assisted approach, better surgical outcomes were observed in the group undergoing robotic-assisted laparoscopy [7]. In our study all patients were obese with BMI more than 30 in both the arms. In obese patients with greater abdominal surface area, adequate spacing between the ports is easily achieved and clashing of the arms is seldom a problem.

In our study, operative time was significantly longer in the robotic-assisted surgery than in the open surgery. As the surgeon’s experience increased, operative time came down but still remains significantly higher than the traditional laparotomy. Several investigators have reported that robotic-assisted surgeries take longer time than the open method [8–12], but it should be recognized that these studies report learning curve data for robotic hysterectomy and other authors have subsequently reported operative times in the range of 165 min [13–15]. We attributed our decreased operative time to many factors like quick adaptation, improved optics and surgeon dexterity. As we gain more experience, we expect to operate in the same time as the open method. The operative procedure itself is much easier with the robotic technique because it mimics intuitively the open procedure as opposed to the laparoscopic procedure for which surgical maneuvering is counterintuitive. Seamon et al. [16] and Lim et al. [17] have reported learning curve for robotic surgery in the treatment of endometrial cancer to be 20 cases to become proficient.

In our study estimated blood loss was significantly less in robotic-assisted surgery compared to open method. Bell et al. [8] and Gaia et al. [18] have reported similar findings in their study. Magnified vision and dexterity helps in better vascular control than the traditional open method. Number of lymph nodes removed by the robotic-assisted method is equal or more than the open surgery in our series which is suggestive of significance. Bell et al. [8] and Gaia et al. [18] have reported similar findings with either methods of surgery. Using lymph node yield as a surrogate determinant for adequacy of surgery, in Boggess series [10], the lymph node yield was much higher, 33 in the robotic-assisted group, than that in the open, 15. In DeNardis series [11] the yield between robot and open was comparable 19 vs 18. In Veljovich series [9] lymph node yield in their robotic patients was lower than that in the open, 13 nodes vs 18 nodes. Ultimately, the best indication of adequacy of surgery would be the efficacy data evaluating recurrence and survival rates.

Length of hospital stay for robotic-assisted group in our study was 1.94 days in comparison to 5.54 days for open group. Decreased length of hospital stay may be secondary to less overall tissue trauma. Several other investigators have reported similar findings in their study [9–11]. This decreases the cost incurred for prolonged hospital stay and also expedites the return to routine work. Certainly, the length of hospital stay is the driving force behind the increased cost of laparotomy. It also decreases loss of work hours for the patient.

Our data indicate a single minor intraoperative complication in robotic-assisted surgery. Minor injury in the external iliac vein during pelvic lymph node dissection was controlled with pressure and prolene sutures and was easily managed with robotic assistance without converting to open method. It was the third case in the robotic-assisted arm, and was due to sudden movement of hot shear in the early phase of learning curve. There was no significant difference in the rate of intra-operative complications between the two arms of our study. Gaia et al. [18] also reported no significant differences in vascular, urologic, or gastrointestinal intraoperative injuries between robotic-assisted and open methods of surgery. No major postoperative complication was noted in either arm. In open surgical arm, five minor (20 %) complications were noted. Bell et al. [8] reported overall postoperative complication rate for laparotomy at 27.5 % and for robotic cohort at 7.5 %. Minor postoperative complication rate was significantly lower for robotic-assisted surgical group.

There is no conversion of robotic-assisted panhysterectomy with lymphadenectomy to open method in our series. All robotic-assisted cases were successfully operated. Low conversion rates from robotic to open method were reported from Veljovich and DeNardis (2 % and 5.4 % respectively) [9, 11]. However in GOG LAP 2 trial the conversion rate was 25 % [19]. The need to convert from a minimally invasive procedure to laparotomy was influenced not only by level of exposure and/or occurrence of an intra-operative complication, but also by the priority a surgeon places on the requirement of comprehensive surgical staging for the patient. Poor exposure was the major indication (70 % of the time) for conversion to laparotomy [20]. Bell et al. [8] has suggested not to offer robotic hysterectomy for a patient with a uterine malignancy with larger than a 14 weeks size uterus, as it is difficult to remove the uterus vaginally. The advantages offered by the robotic platform, including additional retraction and improvements in dexterity that allows the ability to perform complex dissection, significantly contributes to decreased conversion to laparotomy in this group.

In order for robotic surgery for endometrial cancer to be acceptable in the long run we need to accept that it is feasible and it is at least as efficacious as the standard, open approach. Although lymph node count can be a surrogate for adequacy of staging and surgery for endometrial cancer, the ultimate measure of robotic-assisted surgery lies in determining the efficacy of this approach such as recurrence or survival rates. Currently, because robotic assisted surgery for endometrial cancer is in its very early phase, no such efficacy data is available. Other limitations of the da Vinci system at present are physical limitations with bulkiness of the arms of the robot with greater propensity to clash and cost considerations. The absence of haptics or tactile feedback is also an important consideration in robotic-assisted surgery. However, as one gains more experience with the robot, the surgeon is able to use visual cues which enable a “virtual” tactile feel.

Cost is an important concern, especially in our country where affordability is an issue. As our institution has assisted all patients with low cost robotic package, we did not include cost comparison in our study. Any new innovative technology which improves the quality is costlier to begin with as is robotic assisted surgery. We hope cost of robotic surgery will come down in near future as is with any new technology when methods to decrease the cost will be identified. Though the cost of robotic surgery at present is 20 % more than the open surgery, it gets negated by the use of lesser analgesics, decreased wound & systemic complications, early discharge from the hospital and early return to productive work. The direct (robotic technology and associated disposables) cost and indirect (of analgesic, complications, early discharge, early resumption of productive work) cost needs to be analyzed in the future studies.

Conclusion

Robotic assisted hysterectomy and regional lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer is an emerging technique in our country. In comparison to open method, it has advantages of decreased blood loss, less postoperative complication and shorter length of hospital stay. Number of lymph nodes retrieved is equal or higher than the open method. Morbidly obese patients are more suitable for robotic assisted approach, as chances of arm clash decrease due to adequate spacing. All surgeries were done successfully without converting to open method. Ease of extended para-aortic lymph node dissection even in obese patients is an added advantage. As the surgeons gain experience, operative time will decrease further. We conclude that robotic assisted hysterectomy and regional lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer is oncologically feasible technique in comparison to open method. However, large study group and long term follow up data are required to evaluate the recurrence and survival rates.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

No.

Contributor Information

S. P. Somashekhar, Phone: +919845712012, Email: somusp@yahoo.com

Rajshekhar C. Jaka, Email: rajjaka@yahoo.com

References

- 1.Magrina JP, Mutone NF, Weaver AL, et al. Laparoscopic lymphadenectomy and vaginal or laparoscopic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingooophorectomy for endometrial cancer: morbidity and survival. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:376–381. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(99)70565-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malur S, Possover M, Michels W, et al. Laparoscopic-assisted vaginal versus abdominal surgery in patients with endometrial cancer: a prospective randomized trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;80:239–244. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.6069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eltabbakh GH, Shamonki MI, Moody JM, et al. Laparoscopy as the primary modality for the treatment of women with endometrial carcinoma. Cancer. 2001;91:378–387. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010115)91:2<378::AID-CNCR1012>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zullo F, Palomba S, Falbo A, et al. Laparoscopic surgery vs. laparotomy for early stage endometrial cancer: long-term data of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:296–305. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fowler JM. The role of laparoscopic staging in the management of patients with early endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;73:1–3. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1999.5385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahluwalia PK. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1996;3(4 suppl):S1–S2. doi: 10.1016/S1074-3804(96)80129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gehrig PA, Cantrell AS, Abaid LN, et al. What is the optimal minimally invasive surgical procedure for endometrial cancer staging in the obese and morbidly obese woman? Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111:41–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell MC, Torgeson J, Seshadri-Kreaden U, Suttle AW, Hunt S. Comparison of outcomes and cost for endometrial cancer staging via traditional laparotomy, standard laparoscopy and robotic techniques. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111:407–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veljiovich DS, Paley PJ, Drescher CW, Everett EN, Shah C, Peters WA., 3rd Robotic surgery in gynecologic oncology: program initiation and outcomes after the first year with comparison with laparotomy for endometrial cancer staging. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:679. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boggess JF, Gehrig PA, Cantrell L, Shafer A, Ridgway M, Skinner EN, et al. A comparative study of 3 surgical methods for hysterectomy with staging for endometrial cancer: robotic assistance, laparoscopy, laparotomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:360. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeNardis SA, Holloway RW, Bigsby GE, 4th, Pikaart DP, Ahmad S, Finkler NJ. Robotically assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy versus total abdominal hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111:412–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seamon LG, Bryant SA, Rheaume PS, et al. Comprehensive surgical staging for endometrial cancer in obese patients: comparing robotics and laparotomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:16–21. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181aa96c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holloway RW, Ahmad S, DeNardis SA, et al. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer: analysis of surgical performance. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;115:447–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowe MP, Johnson PR, Kamelle SA, Kumar S, Chamberlin DH, Tillmanns TD. A multiinstitutional experience with robotic- assisted hysterectomy with staging for endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:236–43. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181af2a74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holloway RW, Patel SD, Ahmad S. Robotic surgery in gynecology. Scand J Surg. 2009;98:96–109. doi: 10.1177/145749690909800205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seamon LG, Cohn DE, Richardson DL, et al. Robotic hysterectomy and pelvic-aortic lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:1207–1213. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818e4416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim PC, Kang E, Park DH. Learning curve and surgical outcome for robotic-assisted hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy: case-matched controlled comparison with laparoscopy and laparotomy for treatment of endometrial cancer. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17:739–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaia G, Holloway RW, Santoro L, Ahmad S, Silverio ED, Spinillo A. Robotic-assisted hysterectomy for endometrial cancer compared with traditional laparoscopic and laparotomy approaches. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(6):1422–1431. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f74153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker JL, Piedmonte MR, Spirtos NM, et al. Laparoscopy compared with laparotomy for comprehensive surgical staging of uterine cancer: gynecologic oncology group study LAP2. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(32):5331–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seamon LG, Cohn DE, Henretta MS, et al. Minimally invasive comprehensive surgical staging for endometrial cancer: robotics or laparoscopy? Gynecol Oncol. 2009;113:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]