Introduction

Hemophilia attracted considerable attention as an early target for efforts in gene therapy for genetic disease for a number of reasons, including the wide therapeutic window, the latitude in choice of target tissue, the availability of small (Bi et al., 1995; Lin et al., 1997) and large (Evans et al., 1989a; Lozier et al., 2002) animal models of the disease, and the ease of measuring the endpoints, including plasma levels of clotting factor and annualized bleeding rates (Murphy and High, 2008; High, 2012). The initial round of gene therapy trials for hemophilia, which began in 1998, included strategies using plasmids (Roth et al., 2001), retroviral vectors (Powell et al., 2003), gutted adenoviral vectors (GenStar Therapeutics, 2001), and AAV (Manno et al., 2003, 2006), but most efforts have now coalesced around AAV, and multiple trials using this vector are now underway (clinicaltrials.gov NCT01620801; NCT00979238; NCT01687608).

Pathophysiology and Treatment of Hemophilia

An X-linked bleeding disorder, hemophilia results from mutations in the genes encoding either factor VIII (hemophilia A), a cofactor for a critical step in coagulation, or factor IX (hemophilia B), the enzyme that catalyzes the same step. Because the cofactor accelerates the reaction by ∼500,000-fold, the absence of the cofactor is as dire as the absence of the enzyme, and the two entities are indistinguishable clinically. Hemophilia A affects about 1 in 5000 male births, and hemophilia B about 1 in 35,000, with the prevalence the same worldwide. Clinically, the disease is classified as severe (<1% normal circulating levels), moderate (1–5%), or mild (5–30%), and the primary manifestation in those severely affected, the largest category, is recurrent spontaneous bleeding episodes, most frequently into the joints or soft tissues, and more ominously into critical closed spaces such as the intracranial space. The most famous carrier of hemophilia was Queen Victoria1; through her offspring she spread hemophilia through the royal houses of Europe (Massie, 2012). The clinical histories of her affected great-grandsons illustrate compellingly the state of treatment of the disease in the early 20th century; most of these individuals died in childhood or young adulthood from bleeding episodes, for which there was at that time no effective treatment.

The eventual discovery and purification of FIX and FVIII from human plasma (Wagner et al., 1964; Osterud and Flengsrud, 1975) laid the foundation for the first widely available treatment beginning in the late 1960s, and greatly extended life expectancy for boys born with the disease. However, the contamination of these plasma-based products with hepatitis viruses, and eventually HIV, resulted in high rates of infection in people with hemophilia (Pollak and High, 2003). The identification of the genes encoding FVIII (Gitschier et al., 1984) and FIX (Choo et al., 1982) enabled the development of recombinant clotting factor concentrates, but not before many men with hemophilia had died of HIV- or HCV-related disease, which remain leading causes of death in adults with severe hemophilia in the Western world (Darby et al., 1997; Chorba et al., 2001; Evatt, 2006). The high cost of clotting factor concentrates, ∼$100,000/year for those with severe disease who treat on demand, means that optimal treatment is out of reach for 80% of the world's hemophilia population; life expectancy is sharply lower for those born in poorer countries (Evatt and Robillard, 2000; High and Skinner, 2011).

Gene-Based Therapies for Hemophilia

The genetic era in hemophilia began in the early 1980s with the isolation and characterization of the genes for human factor VIII (Gitschier et al., 1984) and factor IX (Choo et al., 1982). The initiation of my own independent research career coincided with these landmark discoveries, and my research group, and many others, exploited these advances to delineate mutations that caused hemophilia, and to produce large amounts of clotting factor for structure–function studies, a goal that had been extremely difficult to achieve through purification from plasma, since all of these factors circulate in very low amounts. Our early focus was on mutations that lead to hemophilia B, partly because the F9 gene is smaller and more tractable than F8, and partly because of the interests of my faculty colleagues at UNC-Chapel Hill, the institution where I started my faculty career. In addition to delineating mutations in patients with factor IX deficiency (Huang et al., 1989; Lozier et al., 1990; Chu et al., 1996), and using expressed mutant protein to understand the molecular basis of the defective clotting (Monroe et al., 1989; Lozier et al., 1990; Chu et al., 1996), we also embarked on a project to isolate the normal canine F9 gene (Evans et al., 1989b). This was based on the proximity of the hemophilia B dog colony in Chapel Hill, and the recognition that every product used to treat hemophilia up to that time had first been evaluated in the hemophilic dog model. The availability of cloning techniques afforded the opportunity to understand the hemophilic dog model at a more fundamental level.

In the pre-PCR era, the isolation of the canine F9 cDNA proceeded through construction of a lambda phage cDNA library from the liver of a normal dog, followed by screening with the human F9 cDNA. The isolated clone showed 86% conservation at the amino acid levels with the human F9 sequence (Evans et al., 1989b). Fortunately, by the time this work was completed, PCR techniques had become available (although there were no commercially available PCR machines at that point), and we were able to use a primitive PCR system rigged up in the lab to isolate the hemophilic F9 cDNA and determine that the causative mutation in the hemophilic dogs was a glycine-to-glutamic acid mutation in a residue of the catalytic domain that has been highly conserved in trypsin-like serine proteases from bacteria to man (Evans et al., 1989a). This same mutation was subsequently described in patients with severe hemophilia B (Giannelli et al., 1990, 1998).

Armed with the normal F9 cDNA, we set out to determine whether it was possible to develop a gene-based approach to treating hemophilia B. As we began this work, we were entirely agnostic about the gene delivery system, and tried a variety of vector delivery systems including nonviral gene delivery, retroviral vectors, adenoviral vectors (Lozier et al., 1994; Walter et al., 1996), and AAV (Herzog et al., 1997). We learned quickly that experiments in tissue culture, though the simplest to conduct, were of only limited utility in predicting results in vivo, and moved to the hemophilia B mouse model that had been constructed by Darrel Stafford (Lin et al., 1997).

Pursuing a variety of approaches, we were eventually able to show that we could achieve long-term expression of FIX at therapeutic levels following intramuscular injection of recombinant AAV in a mouse model (Herzog et al., 1997). Our next goal was to try to move this work forward into the hemophilia B dog model; the major obstacle to this work was preparing enough recombinant AAV-FIX to carry out the studies. We eventually established a collaboration with a biotechnology company in the San Francisco Bay Area that had developed more robust manufacturing capabilities than were to be found in most academic centers at the time. This allowed us to generate the needed reagents, and to achieve long-term expression of canine F9 at low but nonetheless therapeutic levels in the hemophilia B dog model (Herzog et al., 1999). About the same time, our friendly competitor at Stanford, Dr. Mark Kay, was developing similar data in the hemophilic dog model using AAV-FIX in a liver-directed approach, with vector provided through a collaboration with another biotech company (Snyder et al., 1999). Learning that we had similar encouraging results, we submitted the articles back-to-back in Nature Medicine, and then worked together to develop a clinical trial for hemophilia B.

Translation to the Clinic: Safety First

We weighed several factors as we determined whether to conduct the first human trial using AAV for hemophilia in liver versus skeletal muscle. At the time we initiated these studies, there was no clinical experience with injection of AAV into either skeletal muscle or liver, and so there was little to guide us. In favor of muscle was the fact that the delivery procedure was simple—most people have undergone intramuscular injections, whereas at that time, delivery to the liver was done via the hepatic artery, necessitating an invasive procedure in the interventional radiology suite. With muscle as the target tissue, hepatitis B and C, prevalent in the adult hemophilia population because of the older plasma-derived concentrates, would not be a contraindication, whereas the safety of liver-directed AAV gene therapy in hepatitis-infected individuals was unknown.

We knew from biodistribution studies we had conducted that AAV introduced into skeletal muscle was unlikely to lead to germline transmission, whereas similar studies had not been conducted in the setting of liver-directed AAV therapy. As a final point in favor of muscle, judicious choice of the muscle to be injected (e.g., the vastus lateralis, one of the four bellies of the quadriceps, even if resected still leaves a stable knee and a functional quadriceps) meant that in the face of an untoward event, the injected muscle could simply be resected, and the procedure “reversed,” obviously not a possibility with liver. In favor of liver was that it is the natural site of synthesis of factor IX, it contains all the enzymes required for the necessary posttranslational modifications of the molecule, and it is a secretory organ, synthesizing many plasma proteins. This last factor in particular would eventually emerge as the underlying reason for the dose advantage of liver compared with skeletal muscle. Nonetheless, we felt that safety considerations were primary in this early work, and that the risks presented by injection into a peripheral tissue such as skeletal muscle were considerably less than injection into the liver, and thus designed a study in which AAV was injected into skeletal muscle in adult men with severe hemophilia B (Kay et al., 2000; Manno et al., 2003).

These studies were challenging for all involved, the patients, the physicians, and the research team. Intramuscular injection of AAV had not yet occurred in humans. In this first trial, injections were performed under ultrasound guidance, to ensure that the vector was introduced into muscle rather than into a blood vessel in this richly vascular tissue (Fig. 1). Injections proceeded uneventfully; muscle biopsies performed at time points ranging from 2 months to 1 year postinjection provided clear evidence of factor IX expression in the muscle (Fig. 2). Subsequent muscle biopsies performed as long as 10 years after vector injection showed continued expression in human muscle (Buchlis et al., 2012). However, the levels of expression obtained were consistently subtherapeutic (<1%). Moreover, increasing doses in humans required progressively larger numbers of injection sites, until the procedure became infeasible from a clinical tolerability standpoint. The safety data were consistently reassuring however, providing a foundation for moving to hepatic artery infusion.

FIG. 1.

Intramuscular injection of the first subject with severe hemophilia B to receive an AAV vector, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, 1999. Injections were done under ultrasound guidance to avoid injection into the vasculature. A few injection sites were marked with India ink, to facilitate accurate identification of sites for follow-up muscle biopsies.

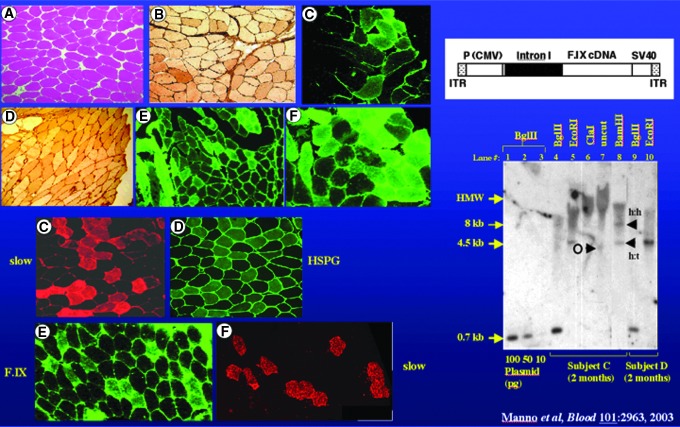

FIG. 2.

Muscle biopsies from subjects injected with AAV-FIX. Left upper panel shows normal appearance of injected muscle on H&E stain, positive immunoperoxidase stain for FIX (darker appearing cells in B and D), and positive immunohistochemical stain for FIX (C, E, and F). Left lower panel shows staining of adjacent sections for slow twitch myosin, a marker for slow twitch fibers (C) and a stain for heparan sulfate proteoglycan, a known receptor for AAV2 (D), and staining of adjacent sections for factor IX (E) and the marker for slow twitch fibers (F), demonstrating the predilection of AAV2 for transduction of slow twitch fibers, based on abundance of the receptor. Right upper panel shows a diagram of the vector, and right lower panel a Southern blot of DNA extracted from muscle biopsies of two subjects, showing bands for vector DNA.

The first trial of AAV infusion into liver was planned as a procedure in the interventional radiology suite, with subjects undergoing infusion of clotting factor concentrate, to effect normal hemostasis, followed by insertion of a catheter into the femoral artery, and fluoroscopically guided placement of the catheter into the hepatic artery. Vector was then infused into the circulation over a period of ∼10 min. Inclusion/exclusion criteria presented a number of challenges. Subjects were screened for antibodies, both neutralizing and nonneutralizing, to AAV, but subjects with neutralizing antibody titers as high as 1:17 were enrolled to the trial, as the appropriate range for “cutoff” had not been established (Manno et al., 2006). Similarly, subjects who were HIV-positive and HCV RNA viral load-positive were allowed to enroll, provided that they had adequate CD4 counts and were stable on a HAART regimen (HIV), and provided they had had a liver biopsy within the past 36 months that had been graded as relatively low on a widely accepted scale for assessing inflammation and fibrosis in liver tissue [Metavir scoring system (Bedossa, 1994)].

Risk of Germline Transmission: An Unexpected Obstacle

The first infusion appeared to proceed uneventfully, but biodistribution studies performed on a semen sample obtained 1 week after vector infusion in the first subject revealed the presence of vector DNA in the semen. This result was unexpected since similar studies had been conducted in hemophilic dogs and had shown no evidence of vector DNA in semen. This occurrence of course underscores the observation that animal studies accurately predict side effects in humans only about 70% of the time. Because of the risk of germline transmission (the possibility that the vector DNA would be transmitted to the subject's offspring), the investigators halted the trial and sought to assess this potential complication (Fig. 3). In the weeks following the injection of the first subject, the vector DNA signal in semen DNA gradually diminished and then disappeared, suggesting that the risk was likely short-term. Moreover, we discovered that the vector DNA was present in the seminal fluid but not in DNA extracted from motile sperm, providing further reassurance about risks related to germline transmission (Manno et al., 2006).

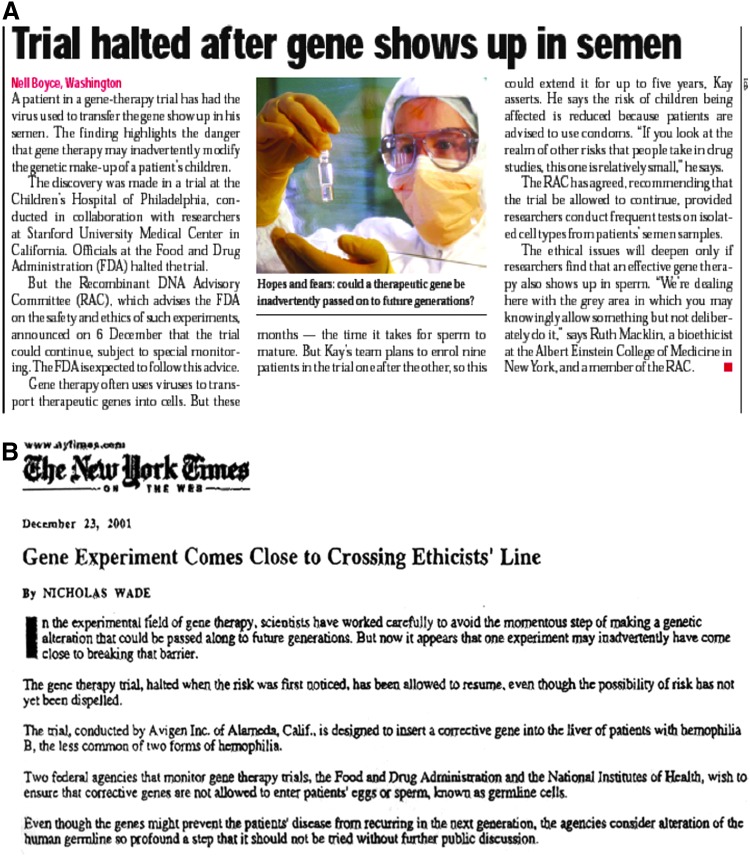

FIG. 3.

Journal and newspaper reports on vector shedding in semen. (A) Brief news article in Nature. (B) Article in the New York Times. Both reported coincident with an NIH Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee meeting convened to discuss risks related to presence of AAV vector in semen in first AAV trial for hemophilia B.

An initial proposal was to track the result in the motile sperm fraction, to see if this was consistently negative, but the challenge in this approach is the use of fairly inexact methods for fractionating semen (density centrifugation) coupled with a highly sensitive method for detecting vector DNA (qPCR). Eventually, we developed a rabbit model for assessing these risks. Rabbits unlike dogs showed the presence of vector DNA in semen; in these animals, it was straightforward to demonstrate that this was a dose- and time-dependent effect, with higher doses associated with longer times to clearing of the vector DNA, but all doses characterized by eventual clearing of vector DNA from semen (Arruda et al., 2001; Schuettrumpf et al., 2006). The protocol was therefore modified to include (1) the option for subjects to bank sperm prior to vector infusion, if they intended to father more children and in the event that the semen failed to clear, and (2) a recommendation to use barrier birth control until three serial specimens were found to be negative for vector DNA. To date, all liver subjects have cleared over time, with the same result found in the AAV8 trial conducted at University College London and St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (vide infra).

The resolution of the issues related to risk of germline transmission occurred over the course of approximately 9 months, and was discussed at two Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee meetings (Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee, 2001, 2002) and one FDA Advisory Committee meeting (Biological Response Modifiers Advisory Committee, 2002). It was also discussed in the pages of Nature and the New York Times (Fig. 3). There is nothing intrinsically harmful to the subject about the transient shedding of vector in the semen, but the events must be understood so that they can be appropriately managed. During most of this time, the trial was on clinical hold, a reasonable maneuver to ensure that no more subjects were put at risk until the consequences were better understood. Nonetheless, in such a circumstance, progress is halted, causing timelines to lengthen, and investigators find themselves trying to resolve complex problems while under intense public scrutiny. This episode thus illustrates clearly one of the issues that beset investigators trying to develop novel classes of therapeutics.

Limitations Imposed by the Human Immune Response to Vector

When the trial resumed with the protocol modifications noted above, dose escalation proceeded uneventfully, until the highest dose was infused. This was the dose predicted to be therapeutic based on large animal studies (Mount et al., 2002), and indeed 2 weeks after vector infusion, the first subject in the high-dose cohort showed an FIX level of 12%, suggesting that the hemophilic dog studies had accurately predicted dosing in humans (Fig. 4a). This level was stable over the ensuing 2 weeks; the subject recounted episodes of minor trauma, such as hitting his hand on a cabinet, that would have normally required treatment with clotting factor, that he withstood without any bleeding. However, just after this, the liver transaminases began to rise, initially only slightly above the upper limit of normal, and at the same time, the F.IX level began to fall very gradually (Manno et al., 2006). The patient was asymptomatic and indeed participated in a major swimming competition during these weeks. The liver enzymes peaked at about 5 weeks after vector infusion, and then gradually returned to normal with no medical intervention. Likewise, the FIX level also inexorably dropped, and by 12 weeks after vector infusion, the subject's FIX level had returned to his baseline of <1%.

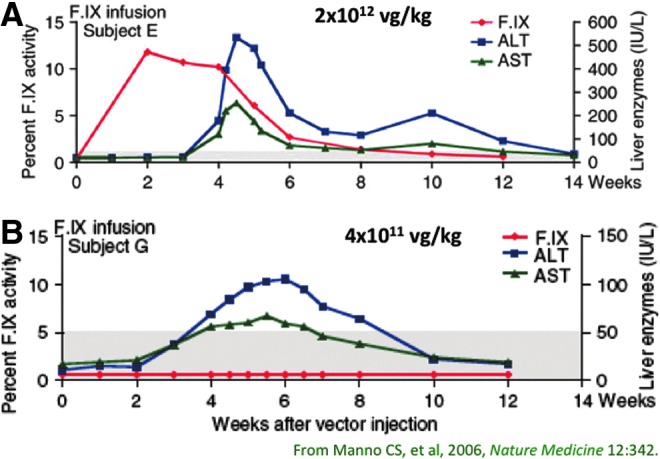

FIG. 4.

Factor IX levels (red) and liver transaminases (blue and green) as a function of time after vector infusion in two subjects in the first AAV liver trial for hemophilia B. (A) Factor IX levels in the first subject in the high-dose cohort rose initially to 12%, remained in this range for 4 weeks, and then slowly declined over the ensuing 8 weeks. Liver enzymes remained normal for 4 weeks, and then rose rapidly and resolved with no medical intervention, in a time course coincident with the loss of FIX expression. (B) In a subsequent subject infused at a lower dose, factor IX levels never exceeded 1%, but liver enzymes rose and fell in the same time course, with the maximum liver enzyme elevation 5-fold lower than seen with the higher dose (note different scales on right y axis).

This series of events was unexpected, since it had not been predictable based on studies in mice, rats, rabbits, hemophilic dogs, or nonhuman primates, and again underscored the fact that animal studies inform, but do not entirely predict, results in clinical studies. Occurring in the fall of 2002, this event was followed by considerable back-and-forth with the regulators. The hypothesis of the investigators was that this was some sort of immune response to the vector; indeed, the consulting hepatologists had suggested a diagnosis of “autoimmune hepatitis” based on clinical and laboratory characteristics, although in the judgment of the investigators it was more likely alloimmune, with the target being some component of the vector.

A number of groups, including our own, set out to develop a mouse model of this series of events, but these efforts were largely disappointing initially (Li et al., 2007a,b; Wang et al., 2007). Meanwhile, the regulatory decision around the clinical trial was to require enrollment of additional subjects at a lower dose; this was disappointing to the investigators since the earlier subjects infused at that dose had shown no evidence of FIX expression; that is, the dose was subtherapeutic, and there was no evidence of liver enzyme elevation, arguing that such a maneuver was likely to be uninformative regarding either toxicity or efficacy. Nonetheless, the trial was amended to include a provision to collect lymphocytes at baseline and at a series of time points after vector infusion, and peptide libraries that spanned the amino acid sequence of both the vector capsid and the FIX protein were prepared, to allow analysis of patient immune responses by IFN-γ ELISPOT. Infusion of the next subject at a dose of 4×1011 vg/kg was indeed subtherapeutic, with no detectable FIX expression, but did result in a mild and self-limited elevation in transaminases (Fig. 4b). PBMCs drawn from the subject showed detectable responses to three distinct pools of peptides (out of 24 total pools) from the vector capsid, but no responses to factor IX–derived peptides. The IFN-γ responses to the three pools of peptides rose and fell in tandem with the rise and fall in liver enzymes.

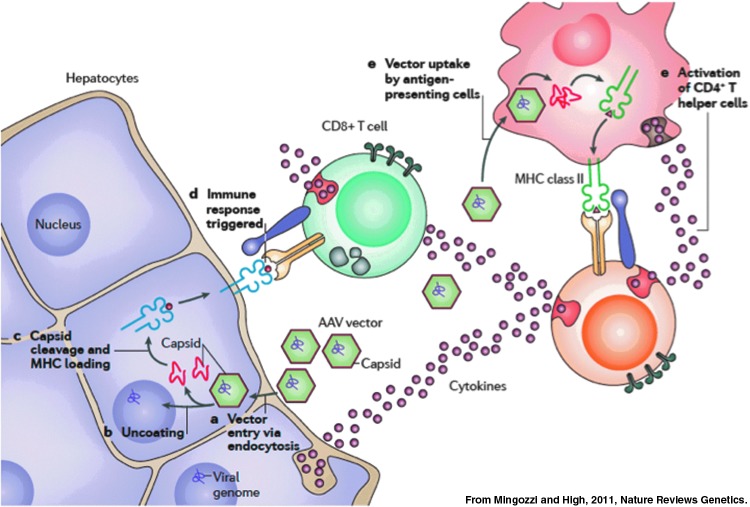

The working hypothesis of the investigators based on these data was that humans harbor memory T cells to AAV, likely generated during initial exposure during childhood to the wild-type virus, that infusion of vector results in expansion of a pool of capsid-specific CD8+ T cells, and that these drive destruction of AAV-transduced hepatocytes, which are targeted because of the presence of capsid-derived peptides displayed via MHC class I on the surface of the transduced cells (Fig. 5). The prediction was that “a short-term immunomodulatory regimen that blocks the response to capsid until these sequences are completely cleared from the rAAV2-transduced cells may permit long-term expression of the donated gene” (Manno et al., 2006).

FIG. 5.

Hypothesis to explain concomitant loss of FIX expression and reversible rise in transaminases. Vector infusion results in two critical events, activation of capsid-specific memory T cells and, after entry of vector into target cells, processing of preformed vector capsid followed by presentation via MHC class I, flagging the transduced hepatocytes for destruction.

Although initially a controversial hypothesis (Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee, 2007), the concept gained traction in the subsequent trial of an AAV8 vector for hemophilia B (Nathwani et al., 2011; Mingozzi and High, 2013), where a short course of immunosuppression was required with higher vector doses. The administration of prednisolone at the first sign of rise in transaminase levels was associated with eradication of the population of capsid-specific T cells from the circulating pool, and resulted in prolonged efficacy (Nathwani et al., 2011). The phenomenon clearly appears to be dose dependent, and to the extent that higher-specific activity FIX variants (Simioni et al., 2009) allow administration of lower doses of vector, it may, in the case of hemophilia B, be possible to avoid the CD8+ T cell response altogether. Whether this dose reduction can also be achieved in the setting of hemophilia A, and other diseases that affect the liver, is not yet clear. Nonetheless, for most patients with hemophilia, the risks of a short course of steroids as adjunctive therapy for gene therapy are far outweighed by the possibility of long-term expression of a clotting factor gene.

Overall, the development of gene-based therapeutics for hemophilia has illustrated the challenges common to novel therapeutics, including the need to evaluate clinical findings that are not predicted by studies in animals, and the need to thoroughly understand the human immune response to a product that is engineered from a virus. Recombinant AAV vectors are not viruses of course, but the close resemblance of the vector capsid to the wild-type virus undoubtedly serves to initiate events with consequences that, if not properly managed, can impair the efficacy of the treatment. The analysis of the human immune response to a recombinant virion has been a fascinating new frontier in biology; basic principles of the immune response to viruses are a relevant starting point, but not fully applicable to a particle that does not replicate and does not drive expression of viral proteins. The need to elucidate this response (Mingozzi and High, 2013), and the clinical investigation of methods to successfully manage or elude it, slowed the translation of efficacious results in large animals (Herzog et al., 1999; Snyder et al., 1999) to efficacy in humans (Nathwani et al., 2011). The contributions of patients, physicians, and investigators have combined to provide the solution (Nathwani et al., 2011) and lay the foundation for improved therapy for hemophilia.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges financial support for the work described from the NIH NHLBI, from Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and from the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. The author also gratefully acknowledges the contributions of many collaborators and trainees over the years.

Author Disclosure Statement

The author holds pending and issued patents in the area of gene therapy for hemophilia. Some of these are licensed to Spark Therapeutics. The author is an employee of and holds equity interest in Spark Therapeutics, which has an interest in developing gene therapy for hemophilia.

We now know that she carried hemophilia B (Rogaev et al., 2009).

References

- Arruda V.R., Fields P.A., Milner R., et al. (2001). Lack of germline transmission of vector sequences following systemic administration of recombinant AAV-2 vector in males. Mol. Ther. 4, 586–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedossa P. (1994). Intraobserver and interobserver variations in liver biopsy interpretation in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 20, 15–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi L., Lawler A.M., Antonarakis S.E., et al. (1995). Targeted disruption of the mouse factor VIII gene produces a model of haemophilia A. Nat. Genet. 10, 119–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biological Response Modifiers Advisory Committee (2002). Summary Minutes, Meeting #32, May10, 2002, Gaithersburg, MD: Available at www.fda.gov/OHRMS/DOCKETS/ac/02/minutes/3855m2.pdf (accessed Oct. 10, 2014) [Google Scholar]

- Buchlis G., Podsakoff G.M., Radu A., et al. (2012). Factor IX expression in skeletal muscle of a severe hemophilia B patient 10 years after AAV-mediated gene transfer. Blood 119, 3038–3041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo K.H., Gould K.G., Rees D.J., and Brownlee G.G. (1982). Molecular cloning of the gene for human anti-haemophilic factor IX. Nature 299, 178–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorba T.L., Holman R.C., Clarke M.J., and Evatt B.L. (2001). Effects of HIV infection on age and cause of death for persons with hemophilia A in the United States. Am. J. Hematol. 66, 229–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu K., Wu S.M., Stanley T., et al. (1996). A mutation in the propeptide of Factor IX leads to warfarin sensitivity by a novel mechanism. J. Clin. Invest. 98, 1619–1625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darby S.C., Ewart D.W., Giangrande P.L., et al. (1997). Mortality from liver cancer and liver disease in haemophilic men and boys in UK given blood products contaminated with hepatitis C. UK Haemophilia Centre Directors' Organisation. Lancet 350, 1425–1431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J.P., Brinkhous K.M., Brayer G.D., et al. (1989a). Canine hemophilia B resulting from a point mutation with unusual consequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86, 10095–10099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J.P., Watzke H.H., Ware J.L., et al. (1989b). Molecular cloning of a cDNA encoding canine factor IX. Blood 74, 207–212 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evatt B.L. (2006). The tragic history of AIDS in the hemophilia population, 1982–1984. J. Thromb. Haemost. 4, 2295–2301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evatt B.L., and Robillard L. (2000). Establishing haemophilia care in developing countries: using data to overcome the barrier of pessimism. Haemophilia 6, 131–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GenStar Therapeutics (2001). GenStar Therapeutics initiates phase i gene therapy clinical trial for hemophilia A gene delivery system utilized for the first time in patients. Available at www.evaluategroup.com/Universal/View.aspx?type=Story&id=15695§ionID=&isEPVantage=no (accessed October10, 2014)

- Giannelli F., Green P.M., High K.A., et al. (1990). Haemophilia B: database of point mutations and short additions and deletions. Nucleic Acids Res. 18, 4053–4059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannelli F., Green P.M., Sommer S.S., et al. (1998). Haemophilia B: database of point mutations and short additions and deletions—eighth edition. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 265–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitschier J., Wood W.I., Goralka T.M., et al. (1984). Characterization of the human factor VIII gene. Nature 312, 326–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog R.W., Hagstrom J.N., Kung S.H., et al. (1997). Stable gene transfer and expression of human blood coagulation factor IX after intramuscular injection of recombinant adeno-associated virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 5804–5809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog R.W., Yang E.Y., Couto L.B., et al. (1999). Long-term correction of canine hemophilia B by gene transfer of blood coagulation factor IX mediated by adeno-associated viral vector. Nat. Med. 5, 56–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- High K.A. (2012). The gene therapy journey for hemophilia: are we there yet? Blood 120, 4482–4487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- High K.A., and Skinner M.W. (2011). Cell phones and landlines: the impact of gene therapy on the cost and availability of treatment for hemophilia. Mol. Ther. 19, 1749–1750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M.N., Kasper C.K., Roberts H.R., et al. (1989). Molecular defect in factor IXHilo, a hemophilia Bm variant: Arg–Gln at the carboxyterminal cleavage site of the activation peptide. Blood 73, 718–721 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay M.A., Manno C.S., Ragni M.V., et al. (2000). Evidence for gene transfer and expression of factor IX in haemophilia B patients treated with an AAV vector. Nat. Gen. 24, 257–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Hirsch M., Asokan A., et al. (2007a). Adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV2) capsid-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes eliminate only vector-transduced cells coexpressing the AAV2 capsid in vivo. J. Virol. 81, 7540–7547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Murphy S.L., Giles-Davis W., et al. (2007b). Pre-existing AAV capsid-specific CD8+ T cells are unable to eliminate AAV-transduced hepatocytes. Mol. Ther. 15, 792–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H.F., Maeda N., Smithies O., et al. (1997). A coagulation factor IX-deficient mouse model for human hemophilia B. Blood 90, 3962–3966 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozier J.N., Monroe D.M., Stanfield-Oakley S., et al. (1990). Factor IX New London: substitution of proline for glutamine at position 50 causes severe hemophilia B. Blood 75, 1097–1104 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozier J.N., Thompson A.R., Hu P.C., et al. (1994). Efficient transfection of primary cells in a canine hemophilia B model using adenovirus-polylysine-DNA complexes. Hum. Gene Ther. 5, 313–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozier J.N., Dutra A., Pak E., et al. (2002). The Chapel Hill hemophilia A dog colony exhibits a factor VIII gene inversion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 12991–12996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manno C.S., Chew A.J., Hutchison S., et al. (2003). AAV-mediated factor IX gene transfer to skeletal muscle in patients with severe hemophilia B. Blood 101, 2963–2972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manno C.S., Pierce G.F., Arruda V.R., et al. (2006). Successful transduction of liver in hemophilia by AAV-Factor IX and limitations imposed by the host immune response. Nat. Med. 12, 342–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massie R.K. (2012). The Romanovs: The Final Chapter. (Random House, New York, NY: ) [Google Scholar]

- Mingozzi F., and High K.A. (2011). Therapeutic in vivo gene transfer for genetic disease using AAV: progress and challenges. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12, 341–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mingozzi F., and High K.A. (2013). Immune responses to AAV vectors: overcoming barriers to successful gene therapy. Blood 122, 23–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe D.M., McCord D.M., Huang M.N., et al. (1989). Functional consequences of an arginine180 to glutamine mutation in factor IX Hilo. Blood 73, 1540–1544 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mount J.D., Herzog R.W., Tillson D.M., et al. (2002). Sustained phenotypic correction of hemophilia B dogs with a factor IX null mutation by liver-directed gene therapy. Blood 99, 2670–2676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy S.L., and High K.A. (2008). Gene therapy for haemophilia. Br. J. Haematol. 140, 479–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathwani A.C., Tuddenham E.G.D., Rangarajan S., et al. (2011). Adenovirus-associated virus vector-mediated gene transfer in hemophilia B. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 2357–2365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterud B., and Flengsrud R. (1975). Purification and some characteristics of the coagulation factor IX from human plasma. Biochem. J. 145, 469–474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak E.S., and High K.A. (2003). Genetic disorders of coagulation. In Oxford Textbook of Medicine. 4th ed. vol. 3, ch 22.6.4. Warrell D.A., Cox T.M., and Firth J.D., eds. Oxford University Press, Inc. New York, NY, pp. 757–767 [Google Scholar]

- Powell J.S., Ragni M.V., White G.C., et al. (2003). Phase 1 trial of FVIII gene transfer for severe hemophilia A using a retroviral construct administered by peripheral intravenous infusion. Blood 102, 2038–2045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee (2001). Minutes of Meeting, December6, 2001. Available at http://osp.od.nih.gov/sites/default/files/Dec01minutes.pdf (accessed Oct. 10, 2014)

- Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee (2002). Minutes of Meeting, March7–8, 2002. Available at http://osp.od.nih.gov/sites/default/files/March2002_0.pdf (accessed Oct. 10, 2014)

- Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee (2007). Immune responses to adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors: NIH Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee Meeting. Available at http://osp.od.nih.gov/sites/default/files/AAV%20summary%20June%202007f.pdf (accessed October10, 2014)

- Rogaev E.I., Grigorenko A.P., Faskhutdinova G., et al. (2009). Genotype analysis identifies the cause of the “royal disease.” Science 326, 817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth D.A., Tawa N.E., O'Brien J.M., et al. (2001). Nonviral transfer of the gene encoding coagulation factor VIII in patients with severe hemophilia A. N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 1735–1742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuettrumpf J., Liu J-H., Couto L.B., et al. (2006). Inadvertent germline transmission of AAV2 vector: findings in a rabbit model correlate with those in a human clinical trial. Mol. Ther. 13, 1064–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simioni P., Tormene D., Tognin G., et al. (2009). X-linked thrombophilia with a mutant factor IX (factor IX Padua). N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 1671–1675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder R.O., Miao C., Meuse L., et al. (1999). Correction of hemophilia B in canine and murine models using recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors. Nat. Med. 5, 64–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner B.H., McLester W.D., Smith M., and Brinkhous K.M. (1964). Purification of antihemophilic factor (Factor VIII) by amino acid precipitation. Thromb. Diath. Haemorrh. 11, 64–74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter J., You Q., Hagstrom J.N., et al. (1996). Successful expression of human factor IX following repeat administration of adenoviral vector in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 3056–3061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Figueredo J., Calcedo R., et al. (2007). Cross-presentation of adeno-associated virus serotype 2 capsids activates cytotoxic T cells but does not render hepatocytes effective cytolytic targets. Hum. Gene Ther. 18, 185–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]