Abstract

Background

Increasing evidence suggests that chronic stress plays an important role in the pathophysiology of several functional gastrointestinal disorders. We investigated whether CB1 and TRPV1 receptors are involved in stress induced visceral hyperalgesia.

Methods

Male rats were exposed to 1-hour water avoidance (WA) stress daily for 10 consecutive days. The visceromotor response (VMR) to colorectal distension (CRD) was measured. Immunofluorescence and Western blot analysis were used to assess the expression of CB1 and TRPV1 receptors in DRG neurons.

Results

WA stressed rats demonstrated a significant increase in the serum corticosterone levels and fecal pellet output compared to controls supporting stimulation of the HPA axis. The VMR increased significantly at pressures of 40 and 60 mmHg in WA stress rats compared with controls, respectively, and was associated with hyperalgesia. The endogenous CB1 agonist anandamide was increased significantly in DRGs from stressed rats. Immunofluorescence and Western blot analysis showed a significant decrease in CB1 and reciprocal increase in TRPV1 expression and phosphorylation in DRG neurons from stressed rats. These reciprocal changes in CB1 and TRPV1 were reproduced by treatment of control DRGs with anandamide in vitro. In contrast, treatment of control DRGs in vitro with the CB1 receptor agonist WIN 55,212-2 decreased the levels of TRPV1 and TRPV1 phosphorylation. Treatment of WA stress rats in situ with WIN or the TRPV1 antagonist capsazepine prevented the development of visceral hyperalgesia and blocked the up-regulation of TRPV1.

Conclusions

These results suggest that the endocannabinoid (CB1) and TRP (TRPV1) pathways may play a potentially important role in stress-induced visceral hyperalgesia.

Keywords: TRPV1, CB1, visceral hyperalgesia, stress, dorsal root ganglion

INTRODUCTION

Stress is an adaptive response that affects endocrine, autonomic and visceral functions in order to maintain homeostasis of the organism in the face of internal or external threats (stressors). Stress is associated with symptom onset, exacerbation and perpetuation in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders.1 A variety of stressors appear to have an important role in the pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which is characterized by altered bowel evacuation, bloating and visceral pain, in the absence of anatomical or biochemical abnormalities.2 Thus, stress-induced visceral hyperalgesia has been suggested as an important biological feature of IBS based on both human and animal studies.1, 3

Accumulating evidence suggests that the endogenous cannabinoid system is involved in the regulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis.4 The endogenous cannabinoid system consists of two receptors: cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) that is expressed primarily in the central and peripheral nervous system, and CB2 receptor that is localized primarily in immune cells. The CB1 receptor is known to play a role in modulating a number of important body functions including pain perception4 and is expressed at high levels in the brain. CB1 agonists suppress the secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and plasma corticosterone levels.5 Mice deficient in the CB1 display increased levels of adrenocorticotrophin and corticosterone and an enhanced susceptibility to chronic variable stress.6 Furthermore, CB1 inhibits gastrointestinal motility in the enteric nervous systems, mainly by inhibition of contractile neurotransmitter release.7 Therefore, there is a rationale for the use of cannabinoid drugs to treat IBS in humans.

Apart from activation of cannabinoid receptors, the endocannabinoid anandamide directly activates the vanilloid receptor 1 (TRPV1) in nociceptive neurons.8 TRPV1 is a ligand-gated ion channel that plays a key role in modulation of the sensation of pain and thermal hyperalgesia.9 Activation of TRPV1 leads to influx of the cations and consequently results in depolarization, neuronal hyperexcitability and pain sensation. In the gastrointestinal tract, TRPV1 is located on the visceral primary afferent neurons.10 Electrophysiological recordings in retrograde labeled neurons innervating the colon reveal that a significant number are capsaicin- and TRPV1-sensitive,11 supporting a role for the TRPV1 channel in visceral sensation and nociception. Taken together, the available data support the involvement of CB1 and TRPV1 receptors in the modulation of visceral nociception. However, the potential relationship between visceral hypersensitivity and, CB1 and TRPV1 receptors in chronic psychological stress has not been examined.

In the present study, we investigated whether CB1 and TRPV1 receptor expression and function play roles in the regulation of sustained visceral hyperactivity in a validated rat model of psychological stress that demonstrates many characteristics of IBS in the human.12

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (200–220 g) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Animals were housed in the animal facility that was maintained at 22°C with an automatic 12 h light/dark cycle. The animals received a standard laboratory diet and tap water ad libitum. All experiments were approved by the University of Michigan Committee on Use and Care of Animals according to National Institutes of Health guidelines. The experimenter was blinded to animal treatment during behavioral experiments.

Water avoidance stress

Repeated water avoidance (WA) stress to adult rats was conducted as described previously.12 The rats were placed on the glass platform in the middle of a test Plexiglas tank that was filled with water (25°C) to 1 cm below the height of the platform. The animals were maintained on the block for 1 hour daily for 10 consecutive days. This repeated WA procedure represents a potent psychological stressor.13 The sham control rats were placed similarly for 1 hour daily for 10 days in the container without water. In a separate study, a group of 8 rats were subcutaneously injected with WIN (2 mg/kg) consecutively for 10 days after rats were subjected to WA stress. A group of 9 WA stress rats were injected IP with capsazepine (5 mg/kg) one hour before the VMR assessment. WIN 55,212-2 and capsazepine were dissolved in 10% DMSO/5% Tween 80/85% saline and the doses were selected based on published reports.14, 15

Measurement of serum corticosterone

Blood was collected from the rat after 1 hour WA stress on day 10 of the stress procedure. Total corticosterone in serum samples was analyzed by the Correlate-EIA corticosterone enzyme immunoassay kit (Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All samples were run in triplicates with standard corticosterone controls and kit calibrators in each analysis. Absorbance at 405 nm was measured with a reference wavelength of 680 nm.

Measurement of fecal pellet output

Fecal pellet output was used to estimate the regulation of distal colonic motility as a validated procedure as described previously.12 Fecal pellets found in the tank were counted at the end of 1-hour WA stress. Control rats were left in home cage for 60 min to count the fecal pellets.

Visceromotor response (VMR) to colorectal distention (CRD)

Rats were deeply anaesthetized with subcutaneous injection of a mixture of ketamine (60 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg), and teflon-coated, 32-gauge stainless steel wires were inserted into the external oblique pelvic muscles superior to the inguinal ligament 5–7 days before the beginning of the experimental procedures. Measurement of VMR to CRD was conducted in rats on the following day after the WA stress procedure was completed as described.12, 16 A flexible latex balloon (4–5 cm) was inserted intra-anally with its end was 1 cm proximal to the anus. Animals with balloon inserted were placed in the animal cage for 30 min before CRD was initiated. The VMR was quantified by measuring electromyographic activity in the external oblique musculature. A series of CRD was conducted to constant pressures of 20, 40, 60 mmHg by a custom-made distension control device. Each distention consisted three segments: a 20-second predistention baseline period, a 20-second distention period, and a 20-second after termination of CRD with a 4-minute inter-stimulus interval. The responses were considered stable if there was less than 20% variability between 2 consecutive trials of CRD at 60 mm Hg. Spike bursts higher than 0.3 mV were regarded as significant and therefore used to estimate the pain response. Rats showing a VMR signal/ratio < 0.05 were excluded from the study. The increase in the area under curve (AUC), which is the sum of all recorded data points multiplied by the sample interval (in seconds) after baseline subtraction, was presented as the overall response during the course of the CRD test.

Mass Spectrometry (LC-APCI/MS-MS)

DRG samples used for mass spectrometry analysis were prepared according to the method described.17 Briefly, L6-S2 DRGs from control and WA stressed rats (n = 5 each group) from rats that had not undergone surgery or CRD were dissected on day 11 of the WA stress procedure, combined and homogenized in 2.0 ml acetonitrile containing 114 pmol of deuterated Arachidonic Acid. The supernatants were concentrated under a constant stream of nitrogen and subjected to LC-APCI/MS analysis. Analysis of anandamide was performed using a ThermoFinnigan Surveyor HPLC system in conjunction with a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (ThermoFinnigan TSQ Quantum Ultra AM). For quantitative analysis, the peak area of AEA ions from the test samples was compared and normalized. The standard curve was obtained by injecting known amounts of anandamide ranging between 1 pM and 100 μM and plotting peak area versus molar concentration.

Administration of cannabinoids in vitro

L6-S2 DRGs from control rats were isolated, chopped and incubated in Minimal Essential Medium (Gibco) supplemented with 3% fetal bovine serum and 50 ng/ml nerve growth factor in 95% air + 5% CO2 at 37°C. A series doses of cannabinoids containing 0–2 μg/ml anandamide or 0–20 μg/ml CB1 agonist WIN were added to the incubation chambers and incubated for 16 hours. The DRGs were then collected for Western blot analysis.

Western blot analysis

L6-S2 DRGs from rats that had not undergone surgery or CRD were taken on day 11 of WA stress procedure and homogenized in ice-cold lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 50 mM NaF, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10% v/v glycerol, 1% v/v Triton X-100, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM Na3VO4, and “Complete” protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Proteins were separated and transblotted to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). The membranes were blocked and incubated with CB1 antibody raised against amino acids 1–77 of the rat CB1 receptor (1:2000; Sigma-Aldrich Co., St Louis, MO) or TRPV1 antibody raised against the N-terminus of TRPV1 of rat origin (1:3000; Santa Cruz Biotech, CA), at 4°C, overnight, and subsequent with secondary antibodies (1:5000; Santa Cruz Biotech) for 1 h and developed using X-ray films by the West Dura Supersignal chemiluminescence kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). In some experiments, equal amounts of total proteins were mixed with anti-TRPV1 antibody (1:50) for immunoprecipitation and probed with anti-phosphorylation antibodies (1:4000, Chemicon) as described previously.18

Immunohistochemistry

L6-S2 DRGs from rats that had not undergone surgery or CRD were removed on day 11 of WA stress procedure and fixed for 2–3 h in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer. Transverse sections through the DRG (10 μm) were cut on a cryostat for immunohistochemistry. Sections were permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 for 2 hours, and then blocked with 10% normal goat serum in PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 for 4 hours at room temperature. Primary antibodies used for overnight incubation were anti-TRPV1 raised against C-terminus of TRPV1 of rat origin (1:400; Chemicon) and anti-CB1 (1:400; Sigma) antibodies. Secondary antibodies Alexa Fluor 488, 594 (1:500) from Molecular Probes were used with 2-hour incubation. Sections were mounted with an anti-fade fluorescence mounting medium for microscope viewing.

Imaging analysis

Immunostained DRG sections were viewed under a Zeiss Axioplan fluorescence microscope, and digitized images were acquired covering the entire DRG in one field under low magnification. Images from 4 to 5 different DRG sections from each rat were pooled for counting in each group. In each rat, 1000–1500 total DRG neurons were counted. Neurons were judged to be positive if they had mean brightness values greater than the corresponding control value stained with the secondary antibody alone. For quantitative analysis of immunofluorescence intensity in DRG neurons, stained DRG sections were randomly selected and the intensity of immunofluorescence staining from the digitized images were converted to gray values ranging from 0 to 255. An appropriate threshold was set such that only specific immunoreactivity was accurately represented and light nonspecific background labeling was not detected. The threshold was the same for all images. The density limited to threshold in the stained cell area was measured for each section and normalized to cell area (100 μm2) by NIH Image-J software.

Statistical analysis

To examine the VMR in response to pressures, the electromyographic amplitudes, represented by calculating AUC, were normalized as percentage of baseline response for the highest pressure (60 mmHg) for each rat and then averaged for each group of rats. This type of normalization has been validated in a similar model to account for individual variations of the electromyographic signals.19 The effects of stress and/or pharmacologic treatment on the VMR to CRD was analyzed by comparing the poststress or posttreatment measurements with the baseline or pretreatment values at each distention pressure using a repeated-measures two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni posttest comparisons. The VMR measurements at day 11 for rats treated with compound or vehicle were expressed as the mean change from baseline for different pressures of distention as described.20 Unpaired Student’s t test was used to examine the data for the expression of TRPV1 and CB1 obtained from Western blot and immunohistochemistry, for corticosterone and fecal pellet output measurements. Results were expressed as means ± SEM. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

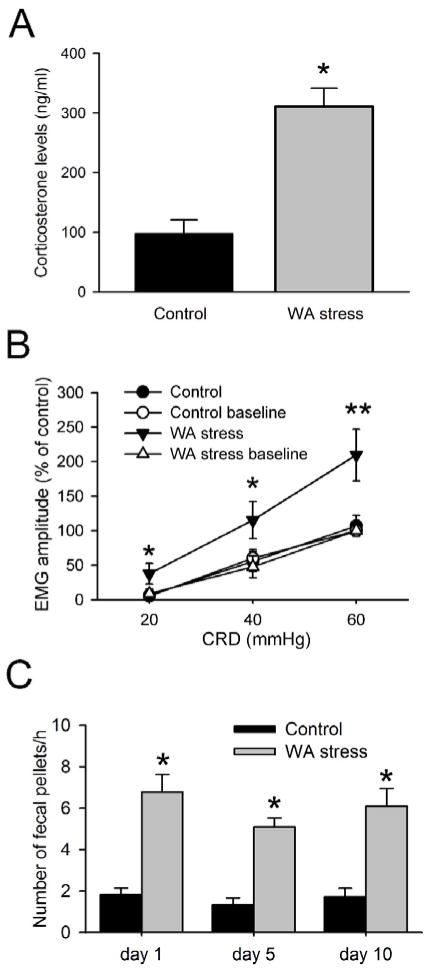

Chronic WA stress resulted in increased visceral nociception

The serum corticosterone level was significantly higher in chronic WA rats compared with the controls (P < 0.05). In control rats, the serum corticosterone level was 97.8 ± 23.2 ng/ml, while it was 310.8 ± 30.9 ng/ml in stressed rats (Fig. 1A). The VMR to grades intensities of CRD was recorded on day 0 before the start of WA stress and sham stress as the baseline level and recorded again on day 11 after chronic stress. In response to CRD, the VMR mean change, expressed as AUC percentage, was significantly higher in the WA stress rats at day 11 compared with the baseline level for the pressures of 20 and 40 mmHg (Fig 1B; P < 0.05). The AUC in the WA stress rats increased 109.7 ± 37.2% compared with the controls for the pressure 60 mmHg (P < 0.01). The VMR in rats following sham stress did not change significantly at day 11 compared with the baseline level. All 8 rats after repeated WA stress showed increased VMR to CRD, which is consistent with visceral hyperalgesia observed in the rats following repeated WA stress.12 Moreover, fecal pellet outputs were significantly increased in rats on day 1, day 5 and day 10 of WA stress compared with the controls (Fig 1C, P < 0.05), indicating the altered colonic motor function following repeated WA stress.

Figure 1. Effect of chronic water avoidance (WA) stress on serum corticosterone level, visceromotor response (VMR) to colorectal distension (CRD), and colonic motor function.

(A) The level of serum corticosterone level was significantly increased in rats following chronic WA stress (n = 8). (B) Electromyographic amplitude expressed as area under curve (AUC) of the raw electromyographic response was significantly increased following chronic WA stress at day 11 compared with the baseline level and the controls (n = 8). (C) Effect of WA stress on distal colonic motor function. Fecal pellets were counted at the end of 1 hour WA stress session from day 1 to day 10. Data are expressed as mean ± SE, n = 12 in each group. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Chronic WA stress increased the level of the endocannabinoid anandamide in DRGs

Representative chromatographs depicting the content of anandamide in DRG tissue extracts are shown in Fig. 2A. The value from control L6-S2 DRGs was 111.3 ng/g tissue weight for anandamide, whereas it was 160.3 ng/g tissue weight in chronic WA stress rats, corresponding to 44% higher anandamide content than that of the controls (Fig. 2B). This percentage increase in anandamide content was similar to the significant increase in anandamide observed in lumbar DRG in a model of neuropathic pain.21 We also measured the content of 2-arachidonylglycerol (2-AG). However, the levels of 2-AG in DRG extracts from both control and WA stressed rats were too low to be detected, possibly due to the natural significant lower content of 2-AG as compared with anandamide in DRGs.21

Figure 2. The level of the endocannabinoid anandamide was increased in L6-S2 DRGs from WA rats.

(A) Representative chromatograph from DRG extracts from control and WA stress rats depicting the relative abundance of endocannabinoid anandamide. (B) The bar graph illustrated the increase in anandamide content in L6-S2 DRGs in rats following chronic WA stress compared to controls. L6-S2 DRGs from 5 rats in each group were combined for sample extraction to reach the adequate weight for LC-APCI/MS-MS analysis.

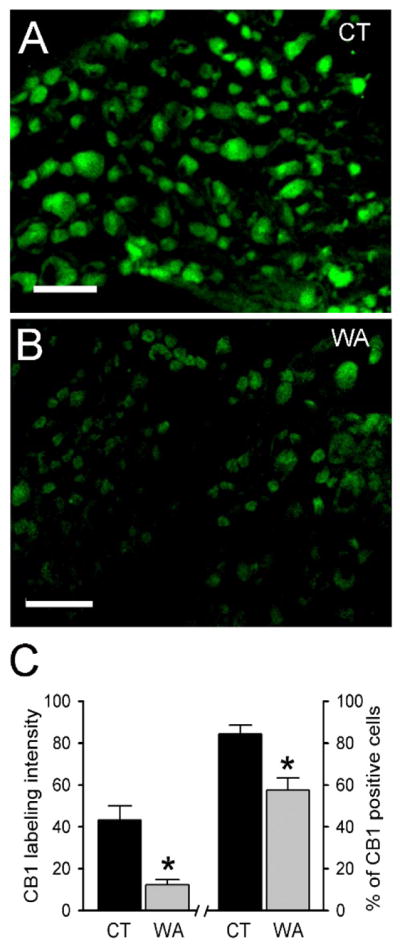

Chronic WA Stress decreased CB1 Expression in DRG neurons

To determine the expression of CB1 receptors, the colonic DRGs (L6-S2) corresponding to the distension area for VMR measurement were identified by retrograde labeling (data not shown). As shown in Fig 3A–B, The CB1 immunoreactivity (IR) signal was greatly reduced in L6-S2 DRGs from chronic WA stress rats compared with controls. In chronic WA stress rats, the CB1 labeling intensity was 43.2 ± 6.7, whereas it was significantly decreased to 12.3 ± 2.4 in DRGs from control animals. The number of CB1 IR-positive neurons was also significantly decreased in stress rats (57.5 ± 5.8 %) compared with the control (84.3 ± 4.2 %) (Fig. 3C; P < 0.05). The decreased CB1 expression was further confirmed by Western blotting analysis. The mean immunoblot band density for CB1 in stressed rats was significantly decreased to 39.8 ± 11.5 % of the control (Fig. 4A–B; P < 0.05). However, the expression level of CB2 was not altered in the rats following repeated WA stress compared with the controls (Fig. 4C–D).

Figure 3. Immunofluorescence staining of endocannabinoid CB1 receptor was decreased in L6-S2 DRGs in WA stress rats.

(A–B) Representative immunofluorescence images of CB1 immunoreactivity (IR)-positive neurons in L6-S2 DRGs from control rats (A) and rats after WA stress (B). Scale bar: 80 μm. (C) CB1 labeling intensity and the number of CB1 IR-positive neurons were significantly decreased in L6-S2 DRGs in rats after WA stress (WA) compared with controls (CT). Data are expressed as mean ± SE, n = 4 in each group. *, P < 0.05.

Figure 4. The protein level of CB1 receptor in L6-S2 DRGs was decreased in WA stress rats.

(A) Levels of CB1 protein measured by Western immunoblot analysis. A significant decrease in the level of CB1 protein was observed in samples from WA stress rats compared with controls. (B) Representative Western blot for CB1 receptor in extracts from L6-S2 DRGs showing a prominent band at ~60 kDa. (C) Level of CB2 protein did not change significantly in the WA stress rats compared with the control (P = 3.87). (D) Representative Western blot for CB2 receptor in extracts from L6-S2 DRGs. Data are expressed as normalized density to β-actin, mean ± SE, n = 5 in each group. *, P < 0.05.

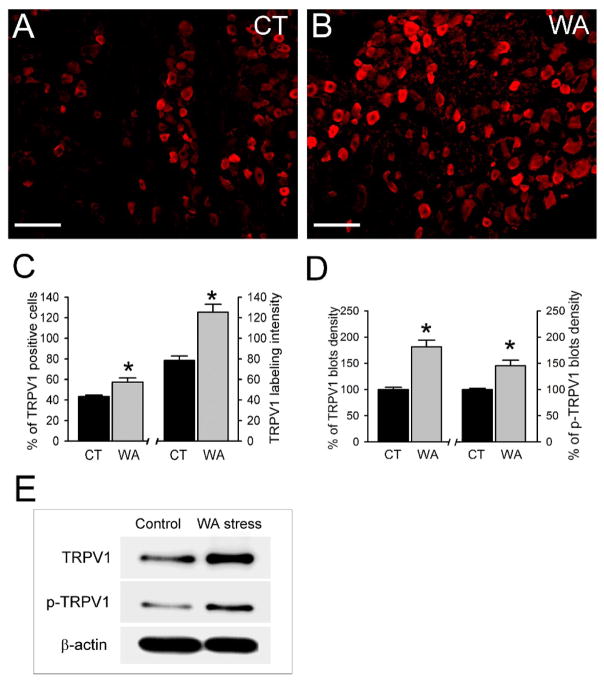

Chronic WA stress increased TRPV1 expression in DRG neurons

As shown in Fig 5A–B, the TRPV1 immunoreactivity signal was increased in L6-S2 DRGs from chronic WA stress rats compared with controls. The number of TRPV1 IR-positive neurons was 43.2 ± 1.4 % in controls rats and increased significantly to 57.3 ± 4.1 % in chronic WA stress rats, while the labeling intensity was increased to 125.3 ± 7.9 in stress rats compared with the control (78.3 ± 4.6) (Fig. 5C; P < 0.05). The changes in TRPV1 expression in chronic WA stress rats was confirmed using Western immunoblot analysis. The protein level of TRPV1 and the level of phosphorylated TRPV1 increased 81% and 45% in L6-S2 DRGs in chronic WA stress rats, respectively, compared with controls as shown by quantitative densitometry of the immunoblots (Fig. 5D–E; P < 0.05).

Figure 5. TRPV1 receptor protein level was increased in L6-S2 DRGs in WA stress rats.

(AB) Representative immunofluorescence images of TRPV1 immunoreactivity (IR)-positive neurons in L6-S2 DRGs from control rats (A) and rats after chronic WA stress (B). Scale bar: 100 μm. (C) Quantification of TRPV1 IR-positive neurons and TRPV1 labeling intensity in L6-S2 DRGs from control and chronic WA stress rats (n = 5). (D) Significant increases in the levels of TRPV1 and phosphorylated TRPV1 (p-TRPV1) were observed in DRGs from chronic WA stress rats compared with controls. Data are expressed as normalized density to β-actin and expressed as % of controls, (E) Representative Western blot for TRPV1 in DRG extracts. *, P < 0.05.

Treatment of control DRGs in vitro with anandamide resulted in decreased CB1 and increased TRPV1 receptor levels

It has been reported that the function of TRPV1 receptor is modulated by the cannabinoid system. We examined whether CB1 and TRPV1 receptor levels in control DRGs were affected by the preferential CB1 agonist anandamide (AEA). Isolated DRGs from control rats were incubated with AEA (0–2 μg/ml) in the culture media for 16 hours. As shown in Figure 6A–B, AEA treatment (2μg/ml) induced significant up-regulation of TRPV1 receptor in control DRGs. Moreover, the levels of CB1 were significantly decreased in DRGs after treatment of AEA at the concentration of 0.5 μg/ml and 2 μg/ml (P < 0.05). Moreover, the phosphorylated TRPV1 significantly increased 85% in DRGs treated with 2 μg/ml AEA compared with the non-treated control (data not shown). These results support the interpretation that the endogenous preferential CB1 agonist AEA can induce reciprocal alterations in the levels of CB1 and TRPV1 receptors in isolated healthy DRG neurons similar to the pattern observed in the WA stressed rats in vivo.

Figure 6. Effects of the endogenous anandamide (AEA) on the expression of CB1 and TRPV1 receptor protein levels in control DRG neurons in vitro.

(A) Treatment with AEA in isolated control DRGs significantly decreased the expression level of CB1 and increased the level of TRPV1 receptor protein levels. (B) Representative Western blotting for TRPV1 and CB1 in extracts from isolated DRGs after AEA treatment for 16 h. Data are expressed as normalized density to β-actin, mean ± SE, n = 4 in each group. *, P < 0.05.

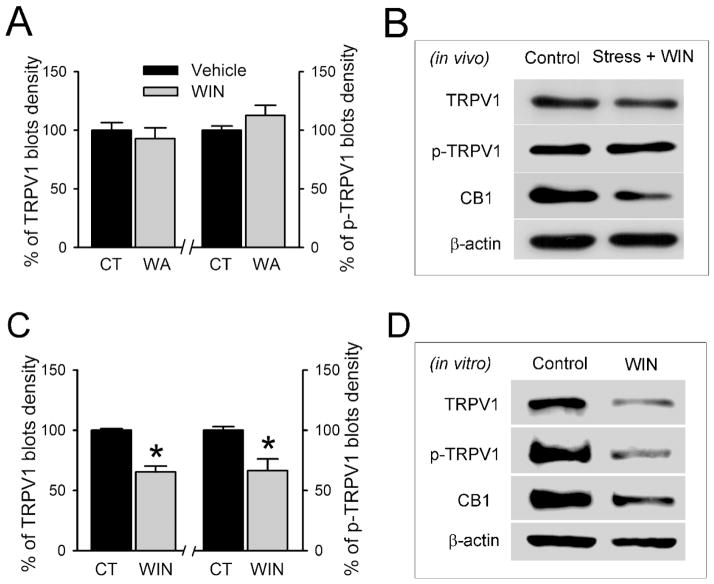

Effect of the exogenous CB1 agonist WIN on CB1 and TRPV1 receptor protein levels in situ and in vitro

It has been shown that cannabinoid agonists have antinociception effects in several pain models.4 In view of our results demonstrating up-regulation of TRPV1 receptors in the stressed rat in situ and that anandamide up-regulates the level of TRPV1 in control DRGs in vitro, we next examined whether the stable CB1 receptor agonist WIN 55,212-2 affects the expression and function of TRPV1 in situ in stressed rats. After rats were injected with WIN (2 mg/kg, s.c. injection) daily for 10 days during the WA stress-induction period, CB1 and TRPV1 receptor levels were examined in L6-S2 DRGs. As shown in Fig. 7B, WIN-injection prevented the up-regulation of TRPV1 but had little effect on CB1 expression level in stress rats. Quantitative densitometry of the immunoblot bands showed that the level of TRPV1 protein after WIN treatment in chronic WA stress rats was 92.9 ± 9.1 % of the vehicle-treated controls (P = 0.48) and that phosphorylated TRPV1 was 112.6 ± 8.7% of the vehicle-treated controls (P = 0.19; Fig. 7A). The effects of WIN treatment on TRPV1 expression in situ was confirmed by in vitro studies. As shown in Fig. 7C–D, WIN treatment in isolated control DRGs in vitro significantly decreased the levels of TRPV1 and phosphorylated TRPV1 compared with the control (P < 0.05). Thus, the effects of anandamide and WIN on the expression TRPV1 receptors in L6-S2 DRGs were quite different, anandamide causing up-regulation and WIN down-regulation in TRPV1 receptor levels and phosphorylation.

Figure 7. Effects of the exogenous CB1 agonist WIN in vivo and in vitro on the expression of TRPV1 and CB1 receptor levels in DRGs.

(A) Repeated WIN treatment in vivo prevents the changes of TRPV1 and phosphorylated TRPV1 (p-TRPV1), but not the CB1 protein, in L6-S2 DRGs in rats following chronic WA stress. (B) Representative Western blotting for TRPV1 and CB1 after repeated WIN treatment. (C) Treatment with WIN in isolated control DRGs in vitro significantly decreased the level of TRPV1 and phosphorylated TRPV1 (p-TRPV1). (D) Representative Western blotting for TRPV1 and CB1 in extracts from isolated DRGs after WIN treatment for 16 h. Data are expressed as normalized density to β-actin, mean ± SE, n = 4 in each group. *, P < 0.05.

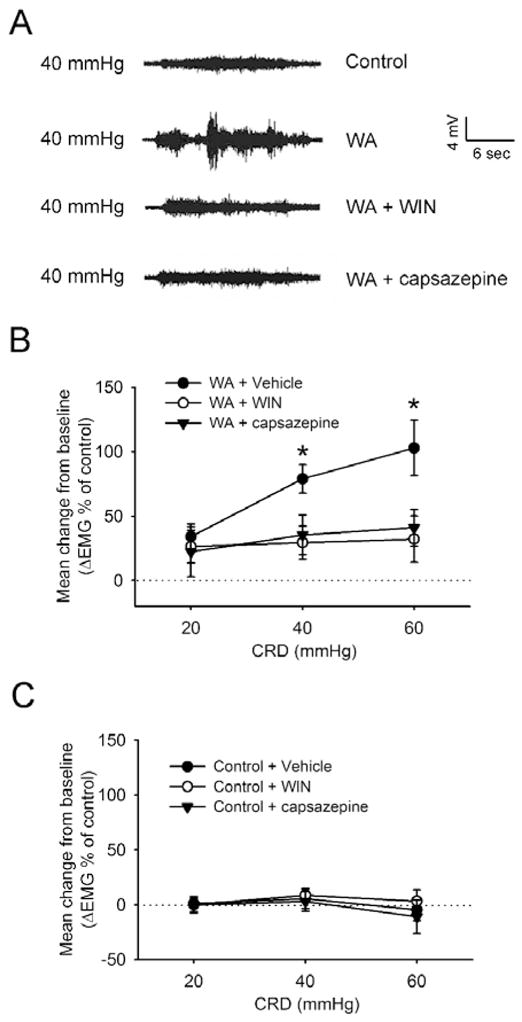

Administration of the CB1 agonist WIN or TRPV1 antagonist capsazepine prevented hypersensitivity in chronic WA stress rats

To further assess the potential therapeutic effect of the CB1 agonist WIN on visceral hyperalgesia in WA stress rats, we measured VMR to CRD in rats that were injected with WIN (2 mg/kg) daily for 10 days during the WA stress-induction period. Another group of rats received IP injection of capsazepine (5 mg/kg) 1 hour before the measurement of VMR. Consistent with previous results, repeated WA stress resulted in an increase in the VMR to CRD (Fig. 8A). As shown in Fig. 8A–B, repeated treatment with WIN significantly decreased the stress-induced increase in the VMR at pressures of 40 and 60 mmHg. The VMR amplitude was significantly decreased to 29.5 ± 2.9% and 32.3 ± 17.8% at CRD pressures of 40 and 60 mmHg compared with vehicle-treated stress rats (77.8 ± 11.8% over baseline level at 40 mmHg and 102.7 ± 23.3% over baseline level at 60 mmHg), respectively (P < 0.05). Similarly, TRPV1 antagonist capsazepine significantly decreased the stress-induced increase in the VMR to CRD (35.4 ± 15.4% at 40 mmHg, 41.0 ± 14.0 % at 60 mmHg, respectively) in stress rats. No significant effects of WIN or capsazepine were observed on the VMR to CRD at all the pressures examined in sham control rats (Fig. 8C).

Figure 8. Treatment of WA rats with the CB1 agonist WIN or TRPV1 antagonist capsazepine reversed visceral hyperalgesia.

(A) Representative electromyography (EMG) recordings depicting the VMR to CRD at 40 mmHg in control rats, WA stress rats, WIN-treated stress rats, and capsazepine-treated stress rats. (B) EMG amplitude expressed as mean change from baseline after treatment with WIN for 10 days or one-time treatment with capsazepine in rats following chronic WA stress. Treatment with WIN or capsazepine abolished the WA stress-induced increase in the VMR to CRD at pressures of 40 and 60 mmHg. (C) EMG amplitude expressed as mean change from baseline after treatment with WIN or capsazepine in sham control rats. Data are expressed as mean ± SE, n = 8 in each group. *, P < 0.05

Discussion

The present study supports a potentially important novel role for the TRPV1 receptor in mediating visceral hyperalgesia in a chronic stress rat model that is modulated by the endocannabinoid CB1 receptor pathway. Water avoidance-induced stress was associated with: i) increased serum corticosterone levels; ii) increased stool output; iii) visceral hyperalgesia in response to colorectal distension; iv) increased levels of the endocannabinoid anandamide (AEA) in DRGs from stressed rats; v) decreased levels of CB1 receptor and increased levels of TRPV1 receptor and TRPV1 receptor phosphorylation in L6-S2 DRGs from stressed rats in vivo and in anandamide-treated DRGs isolated from control rats in vitro; vi) decreased levels of TRPV1 receptor and TRPV1 phosphorylation in control L6-S2 DRGs treated with the selective CB1 receptor agonist WIN in vitro and vii) prevention of visceral hyperalgesia in WA stressed rats treated in vivo with WIN or the TRPV1 receptor antagonist capsazepine.

Evidence supports the concept that visceral hypersensitivity measured in response to colorectal distension is an important factor in IBS.1 We observed that the expression of TRPV1 and TRPV1 phosphorylation were up-regulated in L6-S2 DRG neurons in the WA stressed rats, as well as an increased number of TRPV1 IR-positive neurons. It is likely that the increased number of TRPV1 IR-positive neurons includes DRG neurons innervating the colon the in chronic WA stress rats since >50% of the rodent colon DRG neurons respond to capsaicin and that this response is blocked by capsazepine.11 Up-regulation of TRPV1 has been reported in a variety of gastrointestinal diseases,22,23 including the IBS in human patients.24 Capsaicin-induced pain and hyperalgesia has also been reported in human.25 It has been suggested that intrinsic modulators, such as substance P26 and 5-HT27, can sensitize TRPV1 via phosphorylation and thereby enhance the probability of channel gating by heat or other stimuli.28 The substance P/neurokinin 1 receptor (NK1R) has recently been suggested to play an important role in the maintenance of visceral hyperalgesia in chronic WA stress rats.19 Thus, the increased expression of TRPV1 in L6-S2 DRG neurons may act to facilitate pain signals and maintain peripheral or central sensitization in chronic stress.

The antinociception effects of cannabinoids have an important physiological role in modulating pain sensitivity.4 Recent electrophysiological and neurochemical studies provide new evidence to support a role of endocannabinoids in the modulation of visceral pain. We hypothesized that in chronic stress-induced visceral hyperalgesia endocannabinoids such as AEA act to down-regulate the CB1 receptor in visceral nociceptive pathways which, in turn, results in up-regulation of TRPV1 receptor expression and function. Consistent with this hypothesis, chronic WA stress was associated with increased endogenous AEA, reduced levels of CB1 receptor and increased levels of TRPV1 receptor in L6-S2 DRGs. The majority of CB1 IR-positive DRG neurons also express the TRPV1 receptor.29 This co-localization of CB1 and TRPV1 in DRG neurons provides the anatomical basis for the interaction of these receptors. TRPV1 is a non-selective cation channel and the activity is modulated by its phosphorylation status through PKA/PKC dependent pathways. Activation of CB1 activates inhibitory Gi/o proteins and leads to inhibition of adenylyl cyclase, reduces production of the second messenger cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and inhibits calcium channels,30 which enables the functional basis for interaction with the TRPV1 receptor. Recent reports suggest that application of a CB1 agonist inhibits TRPV1 activation when cAMP-mediated signaling is activated31 and reverses capsaicin-induced thermal hyperalgesia.32 We observed that in chronic WA stress rats, the CB1 receptor level decreased whereas the TRPV1 and its phosphorylation levels increased in colonic DRG neurons. This response was reproduced in control DRGs by treatment with anandamide (AEA) in vitro, possibly through phosphorylation by G-protein-coupled receptor kinases followed by desensitization, internalization, and degradation.33 We hypothesize that the down-regulation of CB1 receptor levels is linked to enhanced expression and function of TRPV1 receptors in DRG neurons in WA stress rats. Of interest, the up-regulation of TRPV1 receptor levels in WA stress rats was attenuated by serial treatment with the selective CB1 receptor agonist WIN in vivo, supporting a potential therapeutic role of WIN or another peripherally acting CB1 receptor agonist in stress-induced visceral hyperalgesia. Consistent with this, WIN reduces visceromotor responses to distension and a CB1, but not CB2, antagonist enhances colitis-induced hyperalgesia.34 Thus, the endocannabinoid anandamide and CB1 receptor agonist WIN had different effects on TRPV1 receptor expression and function and visceral nociception. Endocannabinoids such as anandamide are synthesized “on demand” at the cell surface membrane and act locally as paracrine/autocrine factors. Under conditions of chronic stress, our data suggests that endocannabinoids modulate CB1 (down-regulate) and TRPV1 (up-regulate) receptors in L6-S2 DRGs. Therefore, the endogenous expression of synthetic/degradation enzymes and receptor targets at the cellular level are likely to play a particularly important role in the differential, tissue-specific actions of endocannabinoids. On the other hand, exogenous delivery of cannabinoids such as WIN appears to produce antihyperalgesic and antinociceptive effects via different mechanisms. For example, it has been reported that WIN dephosphorylates and desensitizes TRPV1 via the TRPA1 receptor and contributes to the peripheral antihyperalgesic effects of cannabinoids.31, 32 Therefore, our data demonstrating the prevention of visceral hyperalgesia by WIN in a chronic stress model is consistent with the reported analgesic effect of cannabinoids.4

Although numerous studies have demonstrated that activation of cannabinoid receptors can reduce nociceptive transmission in a variety of animal models, the clinical significance of the analgesic effect remains controversial, along with elucidation of the relevant site(s) of action. The increase in the content of anandamide as well as the reciprocal changes in CB1 and TRPV1 in L6-S2 DRGs in chronic WA stress rats supports a peripheral action for endocannabinoids. Consistent with this interpretation, specific loss of CB1 receptors in nociceptive neurons in the peripheral nervous system significantly reduces analgesic effects produced by endocannabinoids, as well as systemically administered cannabinoids. This suggests that peripheral CB1 receptors are the primary target for cannabinoid-mediated analgesia.35 Our study was not designed to dissect the relative contribution of central vs. peripheral mechanisms to the visceral hyperalgesia observed in the water avoidance-stressed rat. We administered the CB1 agonist WIN and TRPV1 antagonist capsazepine systemically; therefore, WIN and capsazepine could act on receptors in the brain and spinal cord since CB1 and TRPV1 are broadly expressed in the brain and spinal cord. Previous studies support that endocannabinoids can act at CB1 receptors in the central nervous system to modulate pain processing.36 It will be interesting to investigate whether both central and peripheral mechanisms involving CB1 and TRPV1 receptors contribute to chronic stress-induced visceral hyperalgesia in future studies.

Recent studies support the hypothesis that functional interactions occur between glucocorticoids and the endocannabinoid system in situ. For example, mice deficient in the CB1 receptor have high levels of corticotrophin releasing factor, enhanced circadian drive to the HPA axis as well as elevated plasma corticosterone levels,6 suggesting endocannabinoids provide a tonic feedback to control the HPA axis. Exposure of animals to chronic unpredictable stress causes a significant reduction in the expression of CB1 in hippocampus.37 These data support the hypothesis that glucocorticoids exert negative regulation of the expression of CB1 receptors. In accordance with this, we observed elevated serum corticosterone level and decreased expression of CB1 receptor in colonic DRG neurons in chronic WA stress rats. It is possible that the decreased expression of CB1 receptors might be linked to the increased corticosterone level in stressed rats. Supporting this, repeated administration of glucocorticoids or corticosterone increases the contents of anandamide and 2-AG, both in vitro and in situ,38 and significantly reduces the CB1 protein level. Future studies will explore the detailed mechanism(s) underlying the neuroplastic alterations of CB1 and TRPV1 receptors that are associated with chronic stress-induced visceral hyperalgesia.

In summary, visceral hyperalgesia in response to psychological stress is associated with reciprocal changes in the expression and function of CB1 (decreased) and TRPV1 (increased) receptors in L6-S2 DRGs. This novel observation suggests that the endocannabinoid (CB1) and TRP (TRPV1) pathways may play an important role in stress-induced visceral hyperalgesia.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant R01DK052387 and R01DK056997 to JWW from National Institute of Health, by ANMS/SmartPill grant to SH from the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society and by Pilot/Feasibility grant to SH from the Michigan Gastrointestinal Peptide Research Center (NIH grant 5 P30 DK34933).

Abbreviations: The abbreviations used in this paper

- AEA

anandamide

- CB1

cannabinoid receptor 1

- CRD

colorectal distension

- CZP

capsazepine

- DiI

1.1′-dioctadecyl-3, 3, 3, 3′-tetramethlindocarbocyanine methanesulfonate

- DRG

dorsal root ganglion

- HPA

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal

- IR

immunoreactivity

- TRPV1

transient receptor potential vanilloid 1

- VMR

visceromotor response

- WA

water avoidance

- WIN

(R)-(+)-WIN 55,212-2 mesylate salt

Footnotes

The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive licence (or non exclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and its Licensees to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in Gut editions and any other BMJPGL products to exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our licence (http://gut.bmjjournals.com/ifora/licence.dtl).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: All animal procedures were approved by the University of Michigan Committee on Use and Care of Animals according to National Institutes of Health guidelines.

References

- 1.Mayer EA, Naliboff BD, Chang L, Coutinho SVV. Stress and irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;280:G519–G524. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.280.4.G519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tache Y, Bonaz B. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptors and stress-related alterations of gut motor function. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:33–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI30085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez V, Tache Y. CRF1 receptors as a therapeutic target for irritable bowel syndrome. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:4071–4088. doi: 10.2174/138161206778743637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carrier EJ, Patel S, Hillard CJ. Endocannabinoids in neuroimmunology and stress. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord. 2005;4:657–665. doi: 10.2174/156800705774933023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel S, Roelke CT, Rademacher DJ, Cullinan WE, Hillard CJ. Endocannabinoid signaling negatively modulates stress-induced activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Endocrinology. 2004;145:5431–5438. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barna I, Zelena D, Arszovszki AC, Ledent C. The role of endogenous cannabinoids in the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis regulation: in vivo and in vitro studies in CB1 receptor knockout mice. Life Sci. 2004;75:2959–2970. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pertwee RG. Cannabinoids and the gastrointestinal tract. Gut. 2001;48:859–867. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.6.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zygmunt PM, Petersson J, Andersson DA, Chuang H, Sorgard M, Di MV, Julius D, Hogestatt ED. Vanilloid receptors on sensory nerves mediate the vasodilator action of anandamide. Nature. 1999;400:452–457. doi: 10.1038/22761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caterina MJ, Leffler A, Malmberg AB, Martin WJ, Trafton J, Petersen-Zeitz KR, Koltzenburg M, Basbaum AI, Julius D. Impaired nociception and pain sensation in mice lacking the capsaicin receptor. Science. 2000;288:306–313. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5464.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geppetti P, Trevisani M. Activation and sensitisation of the vanilloid receptor: role in gastrointestinal inflammation and function. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141:1313–1320. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sugiura T, Bielefeldt K, Gebhart GF. Mouse colon sensory neurons detect extracellular acidosis via TRPV1. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C1768–C1774. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00440.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bradesi S, Schwetz I, Ennes HS, Lamy CM, Ohning G, Fanselow M, Pothoulakis C, McRoberts JA, Mayer EA. Repeated exposure to water avoidance stress in rats: a new model for sustained visceral hyperalgesia. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G42–G53. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00500.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Million M, Tache Y, Anton P. Susceptibility of Lewis and Fischer rats to stress-induced worsening of TNB-colitis: protective role of brain CRF. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G1027–G1036. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.4.G1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Costa B, Giagnoni G, Franke C, Trovato AE, Colleoni M. Vanilloid TRPV1 receptor mediates the antihyperalgesic effect of the nonpsychoactive cannabinoid, cannabidiol, in a rat model of acute inflammation. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;143:247–250. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Germano MP, D’Angelo V, Mondello MR, Pergolizzi S, Capasso F, Capasso R, Izzo AA, Mascolo N, De PR. Cannabinoid CB1-mediated inhibition of stress-induced gastric ulcers in rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2001;363:241–244. doi: 10.1007/s002100000360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cao Z, Wu X, Chen S, Fan J, Zhang R, Owyang C, Li Y. Anterior cingulate cortex modulates visceral pain as measured by visceromotor responses in viscerally hypersensitive rats. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:535–543. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel HH, Fryer RM, Gross ER, Bundey RA, Hsu AK, Isbell M, Eusebi LO, Jensen RV, Gullans SR, Insel PA, Nithipatikom K, Gross GJ. 12-lipoxygenase in opioid-induced delayed cardioprotection: gene array, mass spectrometric, and pharmacological analyses. Circ Res. 2003;92:676–682. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000065167.52922.F6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong S, Wiley JW. Early painful diabetic neuropathy is associated with differential changes in the expression and function of vanilloid receptor 1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:618–627. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408500200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradesi S, Kokkotou E, Simeonidis S, Patierno S, Ennes HS, Mittal Y, McRoberts JA, Ohning G, McLean P, Marvizon JC, Sternini C, Pothoulakis C, Mayer EA. The role of neurokinin 1 receptors in the maintenance of visceral hyperalgesia induced by repeated stress in rats. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1729–1742. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradesi S, Eutamene H, Garcia-Villar R, Fioramonti J, Bueno L. Stress-induced visceral hypersensitivity in female rats is estrogen-dependent and involves tachykinin NK1 receptors. Pain. 2003;102:227–234. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitrirattanakul S, Ramakul N, Guerrero AV, Matsuka Y, Ono T, Iwase H, Mackie K, Faull KF, Spigelman I. Site-specific increases in peripheral cannabinoid receptors and their endogenous ligands in a model of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2006;126:102–114. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan CL, Facer P, Davis JB, Smith GD, Egerton J, Bountra C, Williams NS, Anand P. Sensory fibres expressing capsaicin receptor TRPV1 in patients with rectal hypersensitivity and faecal urgency. Lancet. 2003;361:385–391. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)12392-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Facer P, Knowles CH, Tam PK, Ford AP, Dyer N, Baecker PA, Anand P. Novel capsaicin (VR1) and purinergic (P2X3) receptors in Hirschsprung’s intestine. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:1679–1684. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.27959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akbar A, Yiangou Y, Facer P, Walters JR, Anand P, Ghosh S. Increased capsaicin receptor TRPV1-expressing sensory fibres in irritable bowel syndrome and their correlation with abdominal pain. Gut. 2008;57:923–929. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.138982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drewes AM, Schipper KP, Dimcevski G, Petersen P, Gregersen H, Funch-Jensen P, rendt-Nielsen L. Gut pain and hyperalgesia induced by capsaicin: a human experimental model. Pain. 2003;104:333–341. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gazzieri D, Trevisani M, Springer J, Harrison S, Cottrell GS, Andre E, Nicoletti P, Massi D, Zecchi S, Nosi D, Santucci M, Gerard NP, Lucattelli M, Lungarella G, Fischer A, Grady EF, Bunnett NW, Geppetti P. Substance P released by TRPV1-expressing neurons produces reactive oxygen species that mediate ethanol-induced gastric injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:581–589. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sugiuar T, Bielefeldt K, Gebhart GF. TRPV1 function in mouse colon sensory neurons is enhanced by metabotropic 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor activation. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9521–9530. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2639-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holzer P. TRPV1 and the gut: from a tasty receptor for a painful vanilloid to a key player in hyperalgesia. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;500:231–241. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Binzen U, Greffrath W, Hennessy S, Bausen M, Saaler-Reinhardt S, Treede RD. Co-expression of the voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1.4 with transient receptor potential channels (TRPV1 and TRPV2) and the cannabinoid receptor CB1 in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Neuroscience. 2006;142:527–539. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hermann H, De PL, Bisogno T, Schiano MA, Lutz B, Di MV. Dual effect of cannabinoid CB1 receptor stimulation on a vanilloid VR1 receptor-mediated response. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:607–616. doi: 10.1007/s000180300052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeske NA, Patwardhan AM, Gamper N, Price TJ, Akopian AN, Hargreaves KM. Cannabinoid WIN 55,212-2 regulates TRPV1 phosphorylation in sensory neurons. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32879–32890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603220200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patwardhan AM, Jeske NA, Price TJ, Gamper N, Akopian AN, Hargreaves KM. The cannabinoid WIN 55,212-2 inhibits transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) and evokes peripheral antihyperalgesia via calcineurin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11393–11398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603861103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sim-Selley LJ, Schechter NS, Rorrer WK, Dalton GD, Hernandez J, Martin BR, Selley DE. Prolonged recovery rate of CB1 receptor adaptation after cessation of long-term cannabinoid administration. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:986–996. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.019612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ibrahim MM, Rude ML, Stagg NJ, Mata HP, Lai J, Vanderah TW, Porreca F, Buckley NE, Makriyannis A, Malan TP., Jr CB2 cannabinoid receptor mediation of antinociception. Pain. 2006;122:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agarwal N, Pacher P, Tegeder I, Amaya F, Constantin CE, Brenner GJ, Rubino T, Michalski CW, Marsicano G, Monory K, Mackie K, Marian C, Batkai S, Parolaro D, Fischer MJ, Reeh P, Kunos G, Kress M, Lutz B, Woolf CJ, Kuner R. Cannabinoids mediate analgesia largely via peripheral type 1 cannabinoid receptors in nociceptors. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:870–879. doi: 10.1038/nn1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cota D, Marsicano G, Tschop M, Grubler Y, Flachskamm C, Schubert M, Auer D, Yassouridis A, Thone-Reineke C, Ortmann S, Tomassoni F, Cervino C, Nisoli E, Linthorst AC, Pasquali R, Lutz B, Stalla GK, Pagotto U. The endogenous cannabinoid system affects energy balance via central orexigenic drive and peripheral lipogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:423–431. doi: 10.1172/JCI17725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hill MN, Patel S, Carrier EJ, Rademacher DJ, Ormerod BK, Hillard CJ, Gorzalka BB. Downregulation of endocannabinoid signaling in the hippocampus following chronic unpredictable stress. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:508–515. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hill MN, Carrier EJ, Ho WS, Shi L, Patel S, Gorzalka BB, Hillard CJ. Prolonged Glucocorticoid Treatment Decreases Cannabinoid CB1 Receptor Density in the Hippocampus. 18. 2008. pp. 221–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]