Abstract

A culturally sensitive educational intervention that encouraged sun protection behaviors among kidney transplant recipients was developed and the short-term efficacy was evaluated. Non-Hispanic White, Hispanic/Latino, and non-Hispanic Black patients, who received a transplant 2–24 months prior to the study, were randomized into two study groups: intervention versus standard of care. Electronic reminders tailored to the weather conditions were sent every two weeks by text message or email. Self-reported surveys and biologic measurements were obtained prior to the intervention and six weeks later. Among the 101 study participants, there was a statistically significant increase in knowledge, recognition of personal risk of developing skin cancer, willingness to change sun protection behavior, and self-reported performance of sun protection in participants receiving the intervention in comparison with those receiving standard of care (p <0.05). The pigment darkening of the sun–exposed forearm and sun damage of the forearm and sunburns/ skin irritation from the sun were significantly less in participants receiving the intervention (p <0.05). Providing sun protection education at the beginning of summer with reminders tailored to weather conditions helped KTRs adopt sun protection practices. This sun protection program for KTRs may be incorporated into the care provided by the nephrologist or transplant surgeon.

Introduction

With advances in immunosuppression, long-term survival among kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) has improved, leading to approximately 180,000 extant recipients in the United States (US). (1) However, immunosuppressive therapy is associated with developing skin cancer, especially squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). (2) Squamous cell carcinoma afflicts approximately 19%–21% of KTRs by 8 years post-transplant, (3, 4) 10–45% by 10 years post-transplant (3–6), and 53%–61% between 15 to 20 years. (3, 4) While the greatest risk of developing SCC is among KTRs with fair skin with 19% developing SCC in 4–9 years post -transplant, SCC also occurs in patients with darker skin tones with 5% developing SCC at 4 to 9 years. (7, 8) Education concerning the importance of protection from ultraviolet radiation (UVR) for all KTRs is necessary for the effective use of sun protection to prevent skin cancer. Use of sun protective clothing, sunscreen, and seeking shade when outdoors are effective ways to reduce exposure to UVR. (9)

Barriers to regular use of sun protection occur at both provider and patient levels. Sixty percent of transplant centers provide a verbal sun protection warning, and 20% provide written information. (10) Clinicians rarely provide education about skin cancer risk after transplantation, nor do they educate effectively enough to promote sun protective behaviors. (10, 11) Typically, sun protection education is delivered during the acute post-operative period (12), when KTRs are focused on recovery and preventing kidney rejection. Hence, most KTRs do not recall having learned that they are at increased risk to develop skin cancer. (12) As a result, sun protective educational messages are not delivered when KTRs are most ready to receive them. Education about sun protection must be delivered to KTRs prior to the first summer after transplantation in climates with seasonal changes in UVR. (13)

People with skin of color comprise 38% of KTRs. (1) People with skin of color have a range of skin tones and come from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds, including African Americans, Asians, Hispanics or Latinos, Native Americans, and Pacific Islanders as well as those of mixed racial and ethnic heritage. A key barrier to regular use of sun protection by KTRs is that people with skin of color have limited personal experience with sunburns (13, 14), and with using sun protection. (15) People of all races/ethnicities with darker complexions may perceive themselves as either at low or no risk for skin cancer because of the belief that dark complexions are protective and they rarely experience sunburn, which is recognized as placing the person at risk to develop skin cancer (16).

This study aimed to develop and evaluate the short-term efficacy of a culturally sensitive educational intervention that encourages sun protection behaviors among KTRs to prevent skin cancer. In contrast to delivery of sun protection education by a dermatologist, we developed an educational intervention intended to be delivered in nephrologists’ or transplant surgeons’ offices and a series of automated electronic reminders sent via text messages or email. It was expected that KTRs would be more receptive to the sun protection information when it is incorporated into a routine visit with a nephrologist or a transplant surgeon than can be achieved by requiring KTRs to make an additional visit to a dermatologist. We hypothesized that KTRs receiving the intervention would engage in more sun protective behaviors, experience fewer sunburns, and have less forearm pigment darkening than participants receiving standard of care.

Materials and Methods

Educational Sun Protection Workbook

The theoretical framework guiding development of the educational workbook was the Theory of Reasoned Action and Planned Behavior. (17) The eleven page sun protection workbook consisted of ten sections devoted to increasing KTRs’ understanding of their probability of developing skin cancer and the relevance of sun protection to avoid skin cancer, a description of skin cancer with pictures of skin cancers in skin of various tones, and presentation of effective sun protection strategies. (18) The sections were titled: Why protect against the sun?, What is skin cancer?, How quickly can skin cancer develop after a kidney transplant?, Why do kidney transplant recipients have a greater chance of getting skin cancer?, People get more sun than they realize, How to protect your skin, Frequently asked questions about sunscreens, Should I use a sunscreen spray, stick, gel or cream?, How much sunscreen do I need to use?, What type of clothing should I wear?, and Remember to protect your skin every day.

Cultural Sensitivity of the Workbook

The workbook was designed to be culturally sensitive to Non-Hispanic White (NHW), Non-Hispanic Black (NHB), or Hispanic/Latino (H/L) KTRs. Originally, three versions of the workbook, tailored to each racial/ethnic group, were developed with respect for KTRs’ culturally-shaped perceptions of preferred skin tone, approaches to describing skin color changes, and outdoor activities commonly enjoyed, which were derived from cognitive interviews. Cognitive interviews to evaluate the workbook were conducted with 24 KTRs comprised of self-identified NHW, NHB, and H/L KTRs. Iterative refinements to the workbook were made until the final set of 3 interviewees accepted the material as respectful of cultural diversity among the users of the workbook. Almost all (23/24) of the KTR respondents reported preferring one workbook that addressed all racial/ethnic group concerns together, rather than three separate workbooks.

When the workbook was identified with only one racial/ethnicity group, NHB or H/L KTRs perceived that only “people like me can get skin cancer from the sun”, which immediately cast doubt on the veracity of the workbook content because NHB and H/L KTRs did not know any NHB or H/L people having a skin cancer. By making the workbook inclusive in scope, the concept that all KTRs needed to use sun protection regardless of racial/ethnicity identity or skin tone became meaningful to the readers.

The workbook presented photographs of skin cancers occurring in all skin types, and addressed NHW, NHB, and H/L values and beliefs about preferences for and the ability to get darker skin color and skin cancer from exposure to the sun. Additionally, the workbook used culturally appropriate language e.g., the term “skin irritation” from the sun was used in place of “sunburn” to describe the response of people with skin of color (e.g., those who self-identified as NHB, H/L) to the sun. Sunburn and skin irritation from sun exposure were depicted as occurring in skin of color as well as in the skin of NHW people after “getting some sun.” Language such as “tan” as a response to sun exposure was explicitly avoided because in our prior research, NHBs and H/Ls reported that they do not think they get a tan rather they stated that they “get dark”. (19) Since many NHB KTRs do not know how to swim, examples of outdoor activities commonly enjoyed by NHW, such as swimming, were not used in the workbook. Family outdoor activities were emphasized because H/L KTRs noted the importance of time spent with the extended family, e.g., a picnic in the park.

Recruitment of Kidney Transplant Recipients

A list of KTRS was created from a database of all patients receiving ambulatory care at Northwestern Medicine within the last 2–24 months. Research coordinators requested permission from the current treating physician to contact his or her patients about participation in the randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of sun protection workbook and electronic reminders. Upon receiving permission from current treating physicians, letters were sent from the treating nephrologist to patients explaining the research study and inquiring about their interest in participation. After a two-week period, research coordinators called patients to inquire about their interest in the study; thus, all eligible patients were recruited. When a racial/ethnic category was filled, then recruitment of KTRs from that category ceased; therefore, not all of the eligible NHW KTRs were recruited. Patients were eligible for study inclusion if they: 1) had a history of kidney transplantation within the last 2–24 months, 2) spoke and read English, 3) could see to read, 4) were between 18–85 years old, and 5) lived in the greater Chicago area. Patients were excluded from the study if they had a prior history of skin cancer, as noted in the medical record or self-reported, or a history of dermatologic disease treated with ultraviolet light, e.g., psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, or under the care of a dermatologist within the last 5 years.

Accrual and randomization were purposefully stratified to assure representation of all three racial/ethnic groups. The accrual goal was 156 subjects (46 NHW, 56 H/L, and 54 NHB) with oversampling of minorities. The power analysis was based on the use of sun protection, our primary outcome. Our prelimiary data showed that 67% of KTRs used sun protection after counseling. The sample size required to sensitively detect a 20% difference in using sun protection between the control and the intervention groups (67% vs. 87%) was 156, assuming an alpha < 0.05 and power >= 0.8 in a two-tailed test.

Educational Workbook Intervention

From May 2013 to July 2013, participants were randomized into the following two study groups: educational intervention versus standard of care sun protection recommendations. Randomization was performed using stratified random blocks using R Core Team (20), to assure equal allocation to groups over the accrual period, in total, as well as within ethnic/racial groups. Sequentially blinded sealed envelopes were provided by the statistician to the study coordinator, to be opened by the participant after the baseline visit. During the first one hour study visit that usually occurred concurrently with a regularly scheduled visit with the nephrologist, all participants provided written informed consent and completed a self-reported survey that collected demographic information and items about the importance of skin cancer, sun protection and sun protection behaviors. During the second 30 minute study visit, the same self-reported survey was administered.

Participants randomized into the intervention group received the sun protection workbook to read at the time of the visit and take home. Over a period of five weeks, three seasonal sun protection reminders were sent by a telephone text message, or email depending on the participant’s preference. The reminders were scheduled to arrive on the Saturday of a summer long holiday weekend, e.g., Fourth of July, in the middle of a week, and on a Friday afternoon preceding a sunny weekend. Participants randomized into the standard of care group did not receive any messages during the study and received the sun protection workbook only after completing the measures at the second visit, at the end of the study.

The pigmentation of all participants, the melanin index, was assessed with non-invasive measures at each visit in the following locations: 1) right forearm in sun exposed skin, 2) right upper inner arm in sun protected skin, and 3) left cheek below the cheekbone. These skin pigmentation measurements were taken using a Mobile Datacollector® DC 3000 spectrophotometer including a Mexameter MX18 probe (Corage + Khazaka Electronic GmbH, Koln, Germany).

A clinical dermatologist (JKR) trained the research coordinators, who were blinded to the group of the participant, to assess the amount of sun damage on each participant’s left forearm (21). The research coordinators and the clinical dermatologist assessed the forearms of 25 individuals used for training purposes and achieved 90% agreement. Sun damage assessment was performed prior to randomization of the individual. At 6 weeks, the research coordinator who assessed sun damage was not the one who distributed the workbook at baseline.

The second visit was scheduled approximately 6 weeks after the first visit and was completed prior to September 3, 2013. A reminder call, email or letter was sent to all participants one week before their second appointment. Participants received a $20 check after the first visit and a $40 check after the second visit in appreciation of their time along with a 6-hour parking voucher for each visit. The Institutional Review Board of Northwestern University approved the research and all participants provided written informed consent.

Measures

Reliability of measures

Survey items were adapted from those published by Glanz et al (22) and used by Robinson in prior research (23). The modified survey items were changed from “In the past 12 months, how many times did you have a red or painful sunburn that lasted a day or more?” to “In the past month, how many times did you have …”. (22) An additional item included in the survey intended to elicit a response from people with skin of color who do not experience sunburn, was “In the past month, how many times did you have skin irritation from the sun, including anytime that even a small part of your skin was irritated for a day or more?” (23) (Supplementary Table. Survey)

The modified survey items were tested and validated by 60 NHW KTRs, 36 of whom were men and 24 were women with a mean age of 47. Participants were accrued from the Department of Dermatology registry. The self-reported measures were validated in a series of telephone interviews at 2 week intervals. With the test and re-test, items that failed to attain the same response 80% of the time were removed. The validated measures were then qualitatively assessed for face validity during cognitive interviews with 24 KTRs consisting of 8 KTRs from each racial/ethnic category. Then the self-reported measures were validated in a series of telephone interviews with 60 people with skin of color, who were not KTRs, using test- re-test methodology. All items attained the same response with at least 80% of the participants.

Survey

The survey consisted of 79 items with responses at baseline and six weeks. The following demographic items were assessed at baseline with 18 items: age, gender, marital status, race/ethnicity, education, employment, annual household income, and skin type (freckling, color of untanned skin, ease of sun burning/sun tanning). Most participants completed the survey in 45 minutes.

Moderators of sun protection performance included perceived personal risk of developing SCC, perceived SCC importance, perceived efficacy of sun protection in preventing skin cancer, and perceived importance of sun protection to self (hat wearing, sunscreen application). Mediators of sun protection performance examined self-efficacy in use of sun protection and intentions to use sunscreen (on a warm sunny day) on the face, neck and ears, trunk, arms and hands, legs and feet; wearing a hat; wearing a shirt with sleeves that covered the shoulders; staying in the shade; intentions to use sun protection regularly in summer even if it is cloudy; knowledge of sun protection; and concern about developing skin cancer.

Outcome Measures

Outcome measures obtained at baseline and 6 weeks were assessed by self-report in the following categories:

The primary outcome was sun protection behaviors, which consisted of hours spent outdoors per week and performance of sun protection with the use of sunscreen, wearing protective clothing and seeking shade. (Supplementary Table Part One, Survey items 1–4, Part Two, Survey items 12–13, Performance of sun protection is presented as a composite of self-reported use of sun protection during the summer on a warm sunny day and on a cloudy day with sunscreen, a shirt with sleeves, a hat, and seeking shade. (Table 2)

Willingness to use sun protection (Supplementary Table Part Three. Survey items 1–20 and Part Six. Survey items 1–9),

Knowledge of skin cancer and sun protection (Supplementary Table Part Four. Survey items 1–9)

Attitudes about concern of developing skin cancer and personal risk of skin cancer, importance of skin cancer and sun protection, attitude about having a tan, confidence that sun protection prevents skin cancer and confidence in using sun protection (concern of developing skin cancer Part Five. Survey item 1, and personal risk of developing skin cancer Part Six. Survey item 10; importance of skin cancer Part Five. Survey item 3, and Part Six Survey item 11); importance of sun protection, Part Five. Survey items 4–9, Part Six. Survey items 12–14, having a tan Part Six. Survey items 15 and 16, and confidence that sun protection prevents skin cancer Part Five Survey item 2, confidence in performing sun protection Part Seven. Survey items 1–5,). (Table 2)

Table 2.

Knowledge, Attitudes, and Sun Protection Behavior Prior to Education

| Baseline Variables | Intervention (n=52) Median (25,75%ile) [Range] |

Standard of Care (n=51) Median (25,75%tile) [Range] |

Wilcoxon Rank Sum p |

|---|---|---|---|

| SELF-REPORTED MEASURES [Range] |

|||

| Knowledge [9–18] | 13 (10, 15) [9, 18] | 15 (11, 16) [9, 18] | 0.051 |

| Attitude Importance of skin cancer, sun protection, having a tan [13–35] |

23 (27, 29) [19, 30] | 25 (24, 26) [14, 28] | 0.259 |

| Concern about developing skin cancer [1–5] |

3 (2,3) [1,5] | 3 (2,4) [1,5] | 0.999 |

| Confidence sun protection prevents skin cancer [1–5] |

3 (2,3) [1,4] | 3 (3, 4) [1,4] | 0.069 |

| Recognize personal skin cancer risk [1–5] |

4 (3,4) [1,4] | 4 (2,5) [1,4] | 0.42 |

| Willingness to change behavior [29–145] |

69 (53, 79) [29, 100] | 75 (58, 88) [29, 100] | 0.137 |

| Confident can regularly do behavior [5–25] |

20 (10, 19) [5, 23] | 21 (8, 22) [5, 24] | 0.121 |

| Sun protection performed [13–66] |

52.5 (42.5, 62.5)[13,62.5] | 55 (45, 65) [13, 61] | 0.422 |

| Sunburn | |||

| None | 46 (85%) | 48 (94%) | 0.109 |

| One | 4 (7%) | 2 (4%) | |

| Two or more | 4 (8%) | 1 (2%) | |

| Skin irritation from sun | |||

| None | 46 (85%) | 44 (86%) | 0.823 |

| One | 4 (7%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Two or more | 4 (8%) | 7 (14%) | |

| BIOLOGIC MEASURES | |||

| Melanin index | |||

| Right upper inner arm (sun protected) [10–2000] |

201 (105, 1022) | 198 (82, 920) | 0.741 |

| Right forearm (sun exposed) [10–2000] |

333 (172, 928) | 332 (158, 874) | 0.432 |

| Cheek (sun exposed)[10– 2000] |

250 (107, 866) | 260 (100, 1119) | 0.870 |

| Sun damage assessment forearm [1–10] |

3 (1, 8) | 3 (1, 8) | 0.825 |

Biologic measures at baseline and 6 weeks included forearm sun damage as assessed by the research coordinator blinded to the study group of the participant. In addition, spectrophotometry measures of right forearm and left mid-cheek pigmentation, which are both potentially sun exposed locations, and the non-sun exposed upper inner aspect of the arm as each subject’s constitutive pigmentation were taken (24). (Table 2) The research coordinator compared each participant’s left forearm with clinical images of chronic sun damage (range 1–10, kappa 0.28–0.76) and selected a score for the sun damage. (20)

Statistical analysis

Demographics, baseline outcome measures, and change in outcomes were compared between groups using Chi-squared tests of association and Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests. Summary statistics are presented as counts and percentages, or median (25th percentile, 75th percentile) and [minimum, maximum] as appropriate. All analyses were run at a nominal type I error rate of 5%, and performed in SASv9.2 (Cary, NC).

Results

Demographics

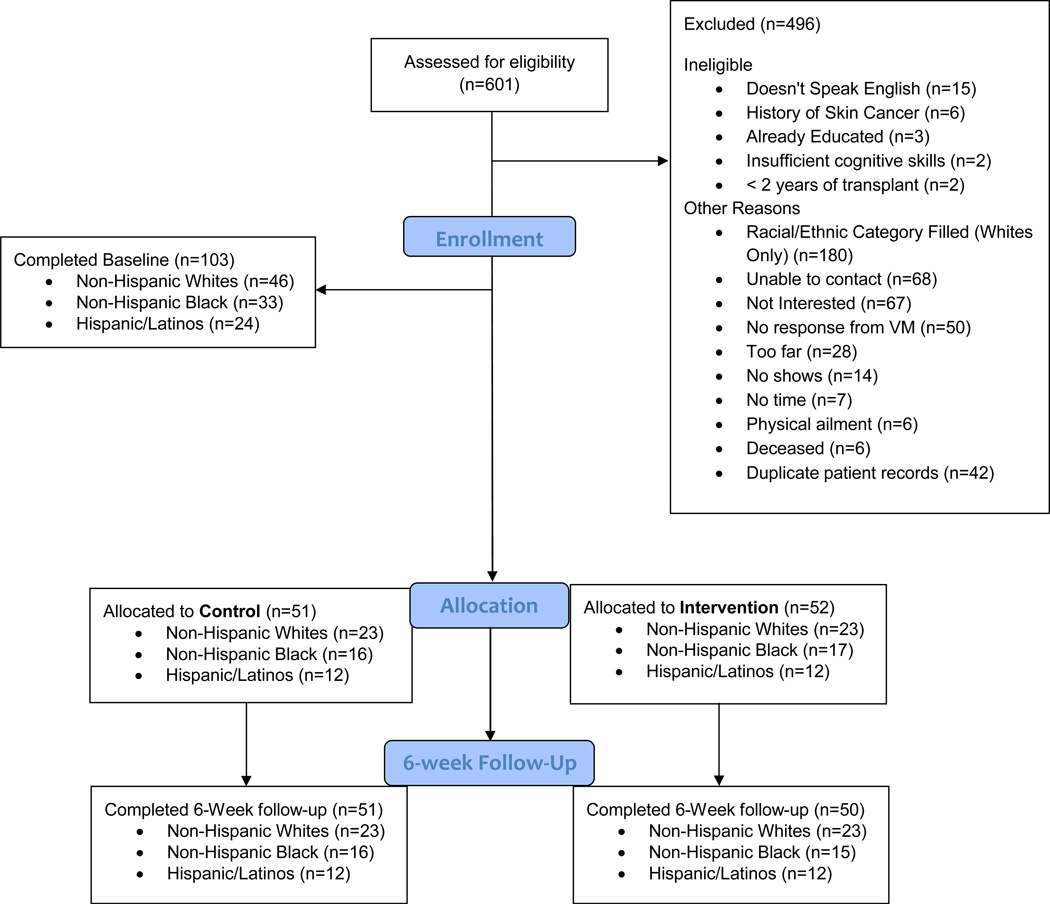

Among the 601 eligible KTRs, there were 103 participants accrued to the study. The participation rate among those asked on the telephone was 71% among NHW, 40% for NHB, and 27% for H/L KTRs. The most common reason for non-participation was the NHW racial/ethnic category was filled. (Figure 1 Consort Diagram) All KTRS unable to speak English were H/L (15 H/L). Those, who remembered being told about sun protection by a health care professional or having a history of skin cancer, were NHW. Refusal to participate for lack of interest (42 NHB, 22 H/L, 3 NHW), or the study location being too far away (8 NHB, 20 H/L) was more common among the racial/ethnic minorities. Failing to keep scheduled baseline appointments was more common among H/L KTRs (13 H/L, 1 NHW). Participants failing to complete the 6 week follow-up visit (n=2) were excluded from the analyses; therefore, the analyses were performed with a sample of 101 participants.

Figure 1.

Consort diagram for the Sun Protection of Kidney Transplant Recipients Study

Among the initial 103 study participants, there were no significant demographic differences between the educational intervention and standard of care groups in terms of demographic variables, time since transplantation, living outside the Midwest or the United States, and work related sun exposure. (Table 1) Among those reporting living outside the United States (n= 26), the most frequent response was Mexico (97%), which has high ambient UVR. All participants remained in the original assigned group for the duration of the study.

Table 1.

Demographics of population

| Characteristics | Intervention (n=52) N (%) |

Standard of Care (n=51) N (%) |

p-value * |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 23 (44) | 23 (45) | 0.95 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 12 (23) | 12 (24) | |

| African American | 17 (33) | 16 (31) | |

| Male | 34 (63) | 34 (67) | 0.69 |

| Married | 31 (57) | 28 (55) | 0.80 |

| College education or higher | 19 (35) | 24 (50) | 0.13 |

| Annual household income | 0.89 | ||

| <10,000 | 5 (10) | 4 (8) | |

| 10,000–19,999 | 8 (15) | 7 (14) | |

| 20,000–34,999 | 10 (19) | 6 (12) | |

| 35,000–50,999 | 10 (19) | 13 (25) | |

| 51,000–100,000 | 11 (21) | 13 (25) | |

| >100,000 | 8 (15) | 8 (16) | |

| Age, years (range), [SD] | 54 (44, 62) [21, 75] | 54 (44, 60) [26, 69] | 0.92 |

| Months since transplant, (range), [SD] |

16 (12, 20) [5, 30] | 13 (8, 20) [3, 29] | 0.09 |

| Lived outside Midwest | 19 (35) | 20 (39) | 0.669 |

| Lived outside United States | 14 (27) | 12 (25) | 0.782 |

| Ever work related sun exposure |

19 (35) | 26 (51) | 0.102 |

p-values from Chi-square test of association and Wilcoxon Rank Sum test (age. Months since transplant).

Knowledge, Attitudes, and Sun Protection Behavior

At baseline, there was no significant difference between the educational intervention and standard of care groups in self-reported measures of knowledge about skin cancer, concern about getting skin cancer, confidence in sun protection preventing skin cancer, willingness to change sun protective behaviors, and sun protection behavior. (Table 2) The lack of reported sunburn or skin irritation from sun exposure may be attributed to participants in this study completing the initial survey prior to seasonal sun exposure in Chicago. There was no difference in the biologic measures of pigmentation and sun damage of the forearm between the two groups.

From baseline to the six week follow-up, there were statistically significant increases in knowledge, concern about developing skin cancer, recognition of personal risk of developing skin cancer, attitudes about the benefit of sun protection, and willingness to change behavior in the intervention group compared to the standard of care group (p<0.01, Wilcoxon rank sum test). (Table 3) KTRs in both groups were not confident that they could regularly perform sun protection. (Table 3)

Table 3.

Change in Knowledge, Attitudes, Sun Protection Behavior and Skin Pigmentation from Baseline to 6 weeks Post-Transplant

| Change in variables | Intervention (n=50) Median (25,75%tile) [Range of Change] |

Standard of Care (n=51) Median (25,75%tile) [Range of Change] |

Wilcoxon Rank Sum p |

|---|---|---|---|

| SELF-REPORTED MEASURES [Range] |

|||

| Knowledge [9–18] | 9 (0, 9) [−9, 18] | 0 (0, 4) [−9, 18] | 0.015* |

| Attitude Importance of skin cancer, sun protection, having a tan [13–35] |

7 (0, 21) [−13, 35] | 0 (0, 4) [−13, 21] | 0.003* |

| Concern about developing skin cancer [1–5] |

2 (0, 1) [1, 3] | 0 (0, 0) [−1, 2] | 0.001* |

| Confidence sun protection prevents skin cancer [1–5] |

1 (0, 1) [−3, 3] | 1 (0, 1) [−3, 3] | 0.159 |

| Recognize personal skin cancer risk [1–5] |

0.5 (1, 2) [−1,3] | 0 (0,0) [−1, 4] | 0.017* |

| Willingness to change behavior [29–145] |

8 (3, 22) [−28, 72] | 0 (−9, 8) [−38, 100] | 0.001* |

| Confidence can regularly do behavior [5–25] |

0 (−5, 20) [−25, 35] | 0 (−10, 10) [−60, 45] | 0.045 |

| Sun protection performed [13–66] | 12.5 (5, 20) [−12.5, 66] | 2.5 (−2.5, 17.5) [−20, 50] |

0.013* |

| Sunburn in the past month | |||

| None | 50 (96%) | 39 (76%) | 0.032* |

| One | 2 (4%) | 12 (24%) | |

| Two or more | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Skin irritation from the sun in the past month |

|||

| None | 50 (96%) | 37 (72%) | 0.001* |

| One | 2 (4%) | 4 (8%) | |

| Two | 0 (0%) | 10 (20%) | |

| BIOLOGIC MEASURES | |||

| Melanin Index | |||

| Right upper inner arm (sun protected) [10–2000] |

−0.8 (−110, 186) | 5 (−193, 108) | 0.497 |

| Right forearm (sun exposed) [10– 2000] |

16.3 (−113, 132) | 44 (−56, 317) | 0.036* |

| Cheek (sun exposed)[10–2000] | −1 (−59, 240) | 15 (−63, 246) | 0.114 |

| Sun damage assessment: right forearm [1–10] |

0 (−4, 2) | 2 (−5, 8) | 0.031* |

Statistically significant Wilcoxon rank sum tests.

Intervention group participants engaged in significantly more sun protection behaviors than standard of care group participants. (p =0.013, Wilcoxon rank sum test). (Table 3) The preferred method of sun protection differed by racial/ethnic group with H/L and NHB KTRs wearing protective clothing, especially long sleeved shirts, and NHW using sunscreen (p = 0.05, Wilcoxan rank sun test, data not shown). Intervention group participants of all racial/ethnic groups reported significantly reduced their average weekly sun exposure from 14 hours a week to 10.5 hours. a week (p <0.001, Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests). During the 6 weeks of the study, the participants in the standard of care group decreased their average weekly sun exposure from 13.5 hours per week to 11 hours per week. The reduction of 3.5 hours of weekly sun exposure in the intervention group compared to 2.5 hours of weekly sun exposure among the standard of care group does not approach statistical significance (p =0.244). At six weeks, the reported absence of sunburns and skin irritation from the sun by the intervention group in comparison with the control group also demonstrated the effectiveness of the use of sun protection (sunburns, p=0.032; skin irritation, p=0.001). (Table 3)

Biologic Measures of Sun Protection

At baseline the melanin index of the right upper inner arm, representing the KTRs’ natural or constitutive pigmentation was the same for the two study groups. [Intervention, Mean 201 (range 105, 1022), Control, Mean 198 (range 82, 920), p=0.741). (Table 2. Biologic Measures) Other biologic measures of sun exposure, melanin index of the right forearm and chronic sun damage of the right forearm, were the same for the two groups.

At 6 weeks, the intervention group demonstrated statistically significant less darkening of the sun exposed forearm skin by spectrophotometry and less sun damage of the forearm than the standard of care group. (Table 3) The lack of pigmentary change in the sun protected skin of the upper inner arm demonstrated that there were no systemic changes that may have influenced skin pigmentation. At the six week follow-up visit, most of the KTRs participating in the intervention group asked to be told their melanin index from the baseline visit because they wanted to know if their sun protection was successful.

Discussion

The KTRs receiving the workbook reported improvement in knowledge, greater recognition of the personal risk of getting skin cancer, greater concern about getting skin cancer, and greater recognition of the need for sun protection to reduce the chance of getting skin cancer. The change in knowledge and attitudes was associated with a reduction in the total amount of sun exposure and use of more sun protection, especially clothing. The reduction of 3.5 hrs of weekly sun exposure in the intervention group has biological significance. SCC development is based upon chronic cumulative sun exposure, thus, reduction in weekly sun exposure will be beneficial over many years. (25) Furthermore, the standard of care group reduced their sun exposure by 2.5 hours per week, which was likely due to awareness of the need for sun protection prompted by the survey and informed consent process, e.g. Hawthorne effect. Both groups initially reported relatively high confidence in their ability to perform sun protection that diluted the effect of the intervention to produce between group differences at six weeks. Thus in clinical practice a significant difference in sun exposure can be expected between the KTRs receiving sun protection education and KTRs who are not educated. The self-reported behavioral change was confirmed by two biologic assessments: pigmentation of the sun exposed forearm, which is a response to unprotected sun exposure, and sun damage of the forearm.

Since clothing was the form of sun protection commonly adopted by people with skin of color, the reduction in darkening of forearm skin among those in the intervention group may be attributed to protection offered by long sleeved shirts. Protection of the forearm in the intervention group was not associated with a significant difference in cheek pigmentation between the two groups, thus, the biologic findings corroborate the self-reported lack of adoption of wearing a hat with a 4 inch brim. KTRs were not confident about their regular performance of sun protection; however, they were willing to try to adopt sun protection behaviors.

Prior studies showed that KTRs have poor understanding about skin cancer risk and the need to use sun protection. Only 5% of KTRs routinely applied sunscreen with high sun protection factors (26) and 35% reported sunburn (27). Compliance with sun protection practices and skin cancer awareness was improved in KTRs highly educated in sun protection and skin cancer awareness by dermatologists. (28, 29) In contrast to the approach of intensive delivery of education by a dermatologist, we developed a brief educational intervention intended to be delivered in nephrologists’ and transplant surgeons’ offices.

In addition to sun protection, KTRs are advised by transplant providers to comply with other behaviors including taking medication, infection prevention, fluid balance, and exercise. (30, 31) Incorporating these self-care practices into KTRs’ life-style involves setting priorities and gaining the confidence to perform the requested behavior. Most of the KTRs participating in the intervention group asked to be told the difference in their melanin index because it was a way to measure the success of their use of sun protection. It is expected that KTRs will continue to engage in sun protection behavior if they observe their own success in achieving effective sun protection.

A limitation of this study is that the KTRs were not surveyed to determine their confidence in their ability to perform sun protection after they knew the change or lack of change in the pigmentation of their forearm skin. Change in pigmentation of their forearm skin would be expected to reinforce KTRs’ confidence in their performance of sun protection. Another way to improve the KTRs’ confidence in their ability to perform sun protection would be keeping a diary to monitor their sun exposure and assess their adherence to sun protection. Since KTRs were offered the option of reading the workbook at home in addition to reading it during the visit, the dosage of the intervention was not controlled. Furthermore, it is not known if subjects opened the text or email reminders. A further limitation is the small size of the study sample, which precluded detailed analyses by racial/ethnic group and the ability to validate the survey with H/L and NHB KTRs. Additional limitations of this study are the limited enrollment of H/L and NHB participants. Recruitment was hampered by not having the workbook and measures available in Spanish for H/L KTRs. For both H/L and NHB KTRs, another barrier to recruitment was transportation to the medical center.

The optimal time for sun protection education is at least 2 months after transplantation during the first sunny month after transplantation. (13) Patients suffering end-organ failure in the pre-transplantation period may not retain health care information as well as they do in the post-transplantation period, when they may be feeling better and have less pressing medical concerns. Additionally, there are logistic considerations to delivery of sun protection education in the pre-transplantation period. Practically, dermatologists’ ability to deliver customized care and sun protection education to each potential KTR in the pre-operative period is limited. Therefore, many transplant programs have provided the sun protection information in the acute post-operative period; however, KTRs are focused on other matters at this time, e.g., ensuring that they take their anti-rejection medicines appropriately. (13)

Presenting sun protection education at the time when KTRs are receptive to adopting sun protection, and when they are becoming active outdoors, contributed to the effectiveness of our educational intervention. Providing sun protection education at the beginning of summer, as recommended by the National Kidney Foundation, and sending electronic reminders tailored to weather conditions every 2 weeks during the study period helped KTRs in this study adopt sun protection. (11) These two elements of a sun protection program for KTRs may be readily incorporated into the care provided by the nephrologist or transplant surgeon. Future research will explore ways to provide the educational program in Spanish as well as English, to examine the role of the KTRs’ skin type in adoption of sun protection behavior, and to explore the sustainability of sun protection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: Supported by R03 CA-159083 to June K. Robinson, MD, from the National Cancer Institute

Abbreviations

- EDW

enterprise data warehouse

- IPA

interpretative phenomenological analysis

- KTR

kidney transplant recipient

- H/L

Hispanic/Latino

- NHB

Non-Hispanic Black

- NHW

Non-Hispanic White

- NKF

National Kidney Foundation

- SCC

squamous cell carcinoma

- UVR

ultraviolet radiation

Footnotes

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01646099

IRB: STU00069552

Author Contributions: June Robinson takes responsibility for the integrity of the paper.

Concept and design: Robinson

Drafting the manuscript: Guevara, Robinson

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Clayman, Gordon, Guevara, Gaber, Friedewald

Statistical analysis and interpretation of the data: Gaber, Guevara, Robinson

Disclosure

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Table S1: Survey

References

- 1. [Accessed February 10, 2014];US Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. Transplant year all organs. Available at: http://www.optn.org/latestData/rptData.asp.

- 2.Jensen P, Hansen S, Moller B, et al. Skin cancer in kidney and heart transplant recipients and different long-term immunosuppressive therapy regimens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:177–186. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70185-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bordea C, Wojnarowska F, Miullard PR, Doll H, Welsh K, Morris PJ. Skin cancers in renal transplant recipients occur more frequently than previously recognized in a temperate climate. Transplantation. 2004;77(4):574–579. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000108491.62935.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernat García J, Morales Suárez-Varela M, Vilata JJ, Marquina A, Pallardó L, Crespo J. Risk factors for non-melanoma skin cancer in kidney transplant patients in a Spanish population in the Mediterranean region. Acta Dermato-Venereol. 2013;93:422–427. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mackenzie KA, Wells JE, Lynn KL, Simcock JW, Robinson BA, Roake JA, et al. First and subsequent nonmelanoma skin cancers: incidence and predictors in a population of New Zealand renal transplant recipients. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation: official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2010;25(1):300–306. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp482. Epub 2009/09/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramsay HM, Reece SM, Fryer AA, Smith AG, Harden PN. Seven-year prospective study of nonmelanoma skin cancer incidence in U.K. renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2007;84:437–439. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000269707.06060.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buoy AG, Yoo S, Alam M, Ortiz S, West DP, Gordon EJ, Robinson JK. Distribution of skin type and skin cancer in organ transplant recipients. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:344–345. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gogia R, Binstock M, Hirose R, Boscardin J, Chren MM, Arron ST. Fitzpatrick skin phototype is an independent predictor of squamous cell carcinoma risk after solid organ transplantation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:585–591. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saraiya M, Glanz K, Briss PA, et al. Interventions to prevent skin cancer by reducing exposure to ultraviolet radiation: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(5):422–466. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Kidney Foundation. [Accessed February 17, 2014];Cancer risk after transplantation: a report to transplant professionals on recipients’ knowledge, awareness of risk, and preventive actions related to malignancy. 2006 www.kidney.org/atoz/pdf/TransMaligReport.pdf.

- 11.Feurstein I, Geller AC. Skin cancer education in transplant recipients. Prog Transplant. 2008;18(4):232–241. doi: 10.1177/152692480801800405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cowen EW, Bilingsley EM. Awareness of skin cancer by kidney transplant patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:697–701. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70149-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim N, Boone S, Ortiz S, Mallet K, Stapleton J, Turrisi R, Yoo S, West D, Robinson JK. Squamous cell carcinoma in solid organ transplant recipients: influences on perception of risk and optimal time to provide education. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1196–1197. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pipitone M, Robinson JK, Camara C, Chittineni B, Fisher SG. Skin cancer awareness in suburban employees: a Hispanic perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;45:118–123. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson JK, Joshi KM, Ortiz S, Kundu RV. Melanoma knowledge, perception, and awareness in ethnic minorities in Chicago: recommendations regarding education. Psycho-oncology. 2011;20:313–320. doi: 10.1002/pon.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buster KJ, You Z, Fouad M, Elmets C. Skin cancer risk perceptions: a comparison across ethnicity, age, education, gender, and income. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2012;66(5):771–779. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.05.021. Epub 2011/08/31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Org Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50:179. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guevara Y, Gaber R, Clayman ML, Gordon EJ, Friedewald J, Robinson JK. Sun protection for diverse audiences: need for skin cancer pictures. J Cancer Educ. 2014 May 2; doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0661-7. (Epub). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson JK, Joshi KM, Ortiz S, Kundu RV. Melanoma knowledge, perception, and awareness in ethnic minorities in Chicago: recommendations regarding education. Psychooncology. 2011 Mar;20(3):313–320. doi: 10.1002/pon.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: 2013. URL http://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKenzie NE, Saboda K, Duckett LD, Goldman R, Hu C, Curiel-Lewandrowski CN. Development of a Photographic Scale for Consistency and Guidance in Dermatologic Assessment of Forearm Sun Damage. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147(1):31–36. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glanz K, Yaroch AL, Dancel M, Saraiya M, Crane LA, Buller DB, Manne S, O’Riordan DL, Heckman CJ, Hay J, Robinson JK. Measures of sun exposure and sun protection practices for behavioral and epidemiologic research. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:217–222. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2007.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robinson JK, Turrisi R, Stapleton J. Efficacy of a partner assistance intervention designed to increase skin self-examination performance. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:37–41. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pershing LK, Tirumala VP, Nelson JL, Corlett JL, Lin AG, Meyer LJ, Leachman SA. Reflectance spectrophotometer: the dermatologists’ sphygmomanometer for skin phototyping? J Investig Dermatol. 2008;128:1633–1640. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strickland PT, Vitasa BC, West SK, Rosenthal FS, Emmett EA, Taylor HR. Quantitative carcinogenesis in man: solar ultraviolet B dose dependence of skin cancer in Maryland watermen. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81(24):1910–1913. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.24.1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szepietowski JC, Reich A, Nowicka D, et al. Sun protection in renal transplant recipients: urgent need for education. Dermatology. 2005;211:93–97. doi: 10.1159/000086435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson JK, Rigel DS. Sun protection attitudes and behaviors of solid-organ transplant recipients. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:610–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le Mire L, Hollowood K, Gray D, et al. Melanomas in renal transplant recipients. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:472–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.07094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ismail F, Mitchell L, Casabonne D, et al. Specialist dermatology clinics for organ transplant recipients significantly improves compliance with photoprotection and levels of skin cancer awareness. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:916–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07454.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gordon EJ, Prohaska TR, Gallant MP, Sehgal AR, Strogatz D, Conti D, Siminoff LA. Prevalence and determinants of physical activity and fluid intake in kidney transplant recipients. Clin Transplant. 2010;24:E69–E81. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2009.01154.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kobus G, Malyszko J, Malyszko JS, Puza E, et al. Compliance with lifestyle recommendations in kidney allograft recipients. Transplant Proc. 2011;43:2930–2934. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.