Abstract

Previous studies have described racial and socioeconomic disparities in the treatment of infertility. Patient factors such as attitudes and awareness may be contributing factors. Since primary care is often the setting that serves as an entry into other areas of medicine, we sought to evaluate men's attitudes and awareness of male infertility in the primary care setting. To do this, we performed a cross-sectional survey of men's attitudes toward men's health issues in 210 men from two primary care clinic waiting rooms in Atlanta, Georgia. The survey was self-administered with closed-ended question items and was approximately 20 min in length. Of the 310 men approached, 210 agreed to participate and returned completed surveys. Overall, 52% of men said they were “very” or “somewhat” familiar with infertility and 25% were familiar with treatments for infertility. Some men had heard of surgery (21%) and medication (35%) as treatments for male infertility. Awareness and familiarity with the condition was greater in high socioeconomic status men (i.e. college graduates or those with income >$100 k per year) but did not differ by race on multivariate analysis. Attitudes toward infertility varied by race with non-Caucasian men being more likely to indicate that infertility is a serious condition, to be concerned about infertility, and to believe it decreases a man's quality-of-life. Therefore, a lack of awareness, but not negative attitudes, may contribute to previously-described disparities in the treatment of infertility.

Keywords: cross-sectional study, health disparities, infertility, patient attitudes and awareness, survey

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, the prevalence of infertility is estimated between 7% and 10%1,2 with 7.3 million couples seeking care for this condition.3 Despite significant scientific advances in assisted reproduction, the high cost of treatment, lack of access to service, and lack of awareness of treatment options make infertility an area especially prone to treatment disparities.4

Factors such as race or ethnicity, measures of socioeconomic status (SES) and gender have all been studied as barriers to care for infertility. A recent systematic review of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology data suggested that in vitro fertilization outcomes do vary by race, but a significant limitation of these data was incomplete race reporting in 35% of cases, and SES factors were not included in the analysis.4 In their study Smith et al.5 found that household income and education, but not race, were important predictors of seeking treatment. Finally, studies from states in the United States with legally-mandated insurance coverage of infertility show that racial disparities persist,6 suggesting that factors besides cost contribute to the disparities described. Drivers of disparities are certainly many, but patient factors, such as beliefs and awareness of infertility and its treatment remain poorly understood.

Up to 50% of infertility cases will involve a male factor, and a male factor is the only identifiable one in approximately 20% of couples.7,8 Despite this, men are less likely to seek services for infertility than women,9 and many men from infertile couples do not undergo a male evaluation,10 despite recommendations from the American Society of Reproductive Medicine in 2012, which advocates evaluation of both partners.11,12 Much of the available information on attitudes and treatment-seeking behaviors pertaining to infertility is based on data collected from women.9,13 Data about men's beliefs and awareness of infertility and its treatment are scant and understudied.

To examine the awareness and attitudes of men on infertility and its treatments, we conducted a cross-sectional survey of a diverse group of men presenting to their primary care doctors. The study was administered with the following objectives: (1) to describe awareness of, attitudes towards and treatment desire for infertility and its treatment, (2) to examine racial and socioeconomic differences in awareness and beliefs as possible explanatory factors for previously-described disparities, (3) to examine demography, awareness or attitudes as predictors of desire for treatment.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study design

We conducted a cross-sectional survey among men at two primary care clinics in Atlanta, Georgia, USA. The infertility questions were part of a larger survey that examined men's health topics, including erectile dysfunction and testosterone deficiency syndrome. The survey was self-administered and required approximately 20 min to complete. Men were recruited in April and May 2012 from clinic waiting rooms. The two clinic sites were selected to capture a socioeconomically and racially diverse population. One clinic site was located in an urban county hospital and the other clinic was part of a university-affiliated internal medicine practice. Inclusion criteria included being at least 20 years of age and able to read English or Spanish. Questions and scales not available in Spanish were translated by two experienced bilingual, native Spanish speakers, and back-translated to ensure accuracy. We estimated a sample size of 200 was needed to find a 20% difference between two groups in response to survey items with two answer choices assuming a power of 80% with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI). A total of 210 men completed the survey. All men in clinic waiting rooms were invited to participate and offered $10 compensation for their time.

Survey

Our survey was developed from existing literature and modified iteratively through expert opinion. Before administration the survey was tested on clinic patients (n = 10) and exit interviews indicated that the survey was understandable and of reasonable length. Selected people underwent one round of cognitive interviewing (n = 5) where men were encouraged to speak their thoughts to the interviewer to ensure that the questions were interpreted as intended. A majority of questions had closed-ended responses with yes/no/not sure answers or a five-point Likert scales.

Attitudes toward infertility and its treatment were evaluated by responses to statements by the use of a five-point Likert scale: “strongly disagree,” “disagree,” “neutral,” “agree,” and “strongly agree.” Treatment desire was measured by responses to the following question: “if the doctor said you had the following condition (infertility), would you desire treatment with “yes, definitely,” “yes, probably,” “not sure,” “no, probably not,” and “no, definitely not” as possible answer choices. Awareness was assessed with yes/no/not sure responses to the question “have you read or heard of…” for several items including “infertility,” “medications to treat infertile men,” “surgeries to treat infertile men,” “medications to treat infertile women,” and “surgeries to treat infertile women.” Men were also asked “how familiar are you with the following conditions: (infertility)” and “how familiar are you with treatments for the following conditions: (infertility)” with the following answer choices: “not at all familiar,” “not too familiar,” “somewhat familiar,” “very familiar” and “not sure.” The five-point Likert scale results were dichotomized for analysis.

Additional information on each study participant included age, race, education, income, marital status, insurance coverage, religious affiliation, number of living children, and desire for more children at this point in their life. Race was compared as Caucasian (n = 67) versus non-Caucasian (n = 143) respondents. To examine disparities by SES a single binary variable was created to include education and income. High SES was defined as respondents who reported either a college degree or an income over $100 k per year.

Statistical analysis

The variables under study were examined by using JMP statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) to describe all infertility-related and demographic questionnaire items (n = 210). Attitude items measured on five-point Likert scales were initially analyzed as ordinal variables and subsequently dichotomized. Bivariate analyses accompanied using Pearson chi-squared tests were carried out to examine the relation of awareness, attitudes and demographic categories. All associations found to be statistically significant with a two-sided alpha error of <0.05 were further characterized by calculating crude odds ratios (OR) and 95% CI. To assess demographic determinants of awareness, attitudes, and treatment desire more fully, multivariate logistic regression models were used for each of these measures. Independent variables in each multivariable model included age (20–39, 40–59, ≥60), race (Caucasian vs non-Caucasian) and SES (college degree or income >$100 000 vs the rest). For treatment desire, the analysis was limited to men <60 years old, because it was assumed that most men over 60 years old would not want to have more children. Therefore, only 161 men were included in the sub-analysis for predictors of treatment desire. All multivariate analyses demonstrated goodness-of-fit and were checked for interacting effects of covariates. Only completed surveys were included in the final analysis.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board at Emory University approved this study before recruitment of participants.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

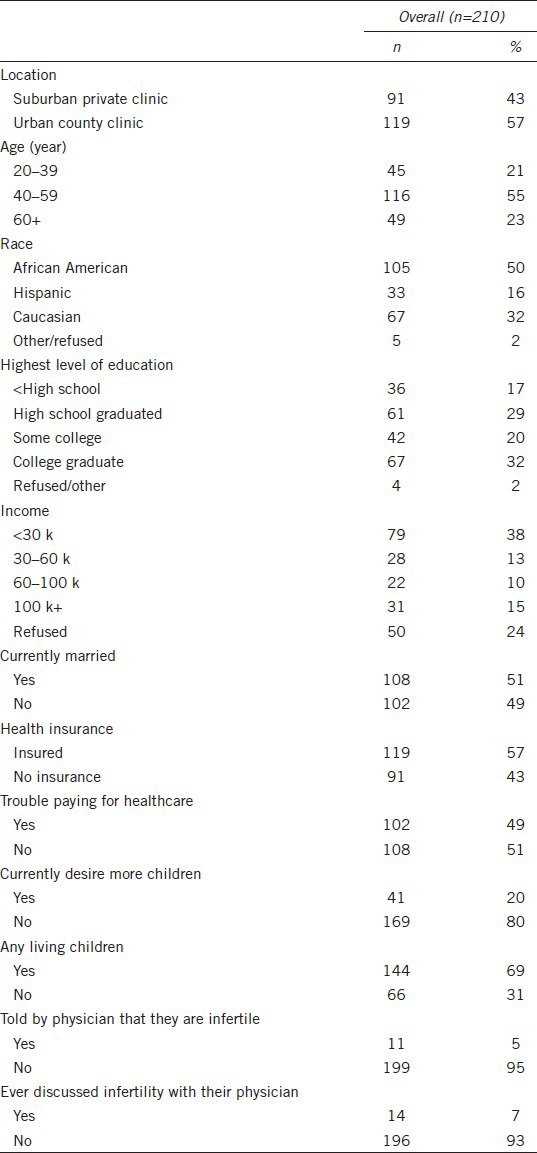

Of the 310 men eligible for the study, 210 (68%) agreed to participate and returned completed surveys. The baseline characteristics of these 210 respondents are shown in Table 1. About half of the study participants were African American, 32% non-Hispanic caucasian, 16% Hispanic, and 2% identified themselves as “other” or preferred not to answer. About a third (35%) of men reported either a college degree or an income over $100 k per year and thus were considered in the “high SES” cohort. A majority (81%) had graduated from high school and about half (49%) reported difficulty in paying for healthcare. Among the respondents, 69% of men reported having living children, and 20% said they currently desire more children. Only 7% had ever discussed infertility with their physician and 5% had been told that they are infertile.

Table 1.

Characteristics of respondents

Awareness about infertility and its treatment

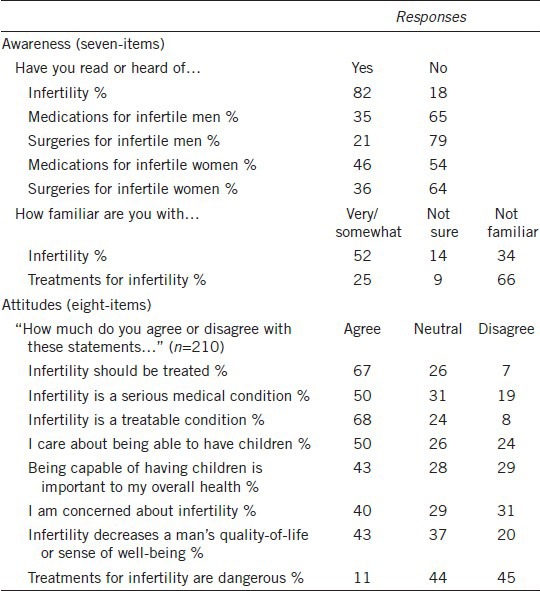

In all, 82% of men said they had heard of infertility, whereas 52% were “very” or “somewhat” familiar with the condition and 25% were familiar with treatments for infertility (Table 2). Only 21% of men were familiar with both condition and treatments. Some men had heard of surgery (21%) and medication (35%) to treat infertile men with 15% reporting awareness of both treatment options.

Table 2.

Summary of responses to questions about awareness of and attitude towards infertility (n=210)

Attitudes about infertility and its treatment

A majority of participants agreed that infertility should be treated (67%), and that infertility was a treatable condition (68%), and relatively few (11%) believed treatments for infertility were dangerous (Table 2). Over half of the men agreed with the statement “infertility is a serious medical condition,” 43% agreed that “being capable of having children is important to my overall health,” 43% agreed that “infertility decreases a man's quality-of-life,” and 40% agreed to the statement “I am concerned about infertility.”

Racial and socioeconomic variation in awareness and attitudes

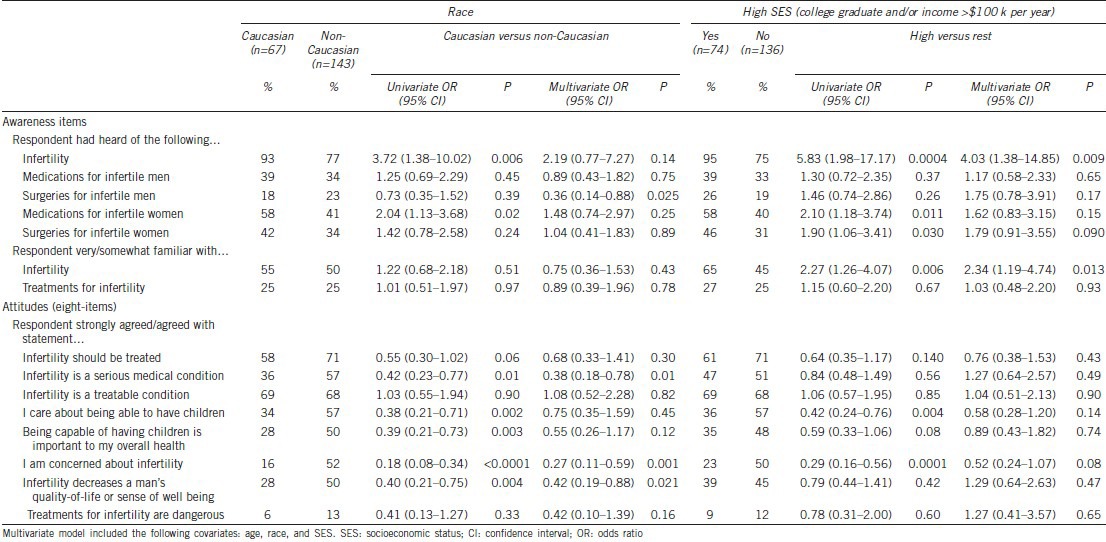

Racial and socioeconomic associations with all infertility awareness and attitude items were examined (Table 3). Significant variation by SES was observed in two awareness items. High SES men (vs rest of cohort) were more likely to have heard of infertility (95% vs 75%, OR: 4.03, 95% CI: 1.38–14.85, P = 0.009), to be very or somewhat familiar with the condition (65% vs 45%, OR: 2.34, 95% CI: 1.19–4.74, P = 0.013). Caucasian men were more likely to have heard of infertility, however when adjusted for age and SES this association was no longer statistically significant. Three of the eight attitude measures varied by race, but no attitudes items varied by SES. Caucasian men (vs non-Caucasian men) were less likely to agree with the following statements: “infertility is a serious medical condition” (36% vs 57%, OR: 0.38, 95% CI: 0.18–0.78, P = 0.01), “I am concerned about infertility” (16% vs 52%, OR: 0.27, 95% CI: 0.11–0.59, P = 0.001), and “infertility decreased a man's quality-of-life” (28% vs 50%, OR: 0.42, 95% CI: 0.19–0.88, P = 0.021).

Table 3.

Association between participant demographic characteristics and measures of awareness and attitudes toward infertility (n=210, includes all age groups)

Predictors of treatment desire

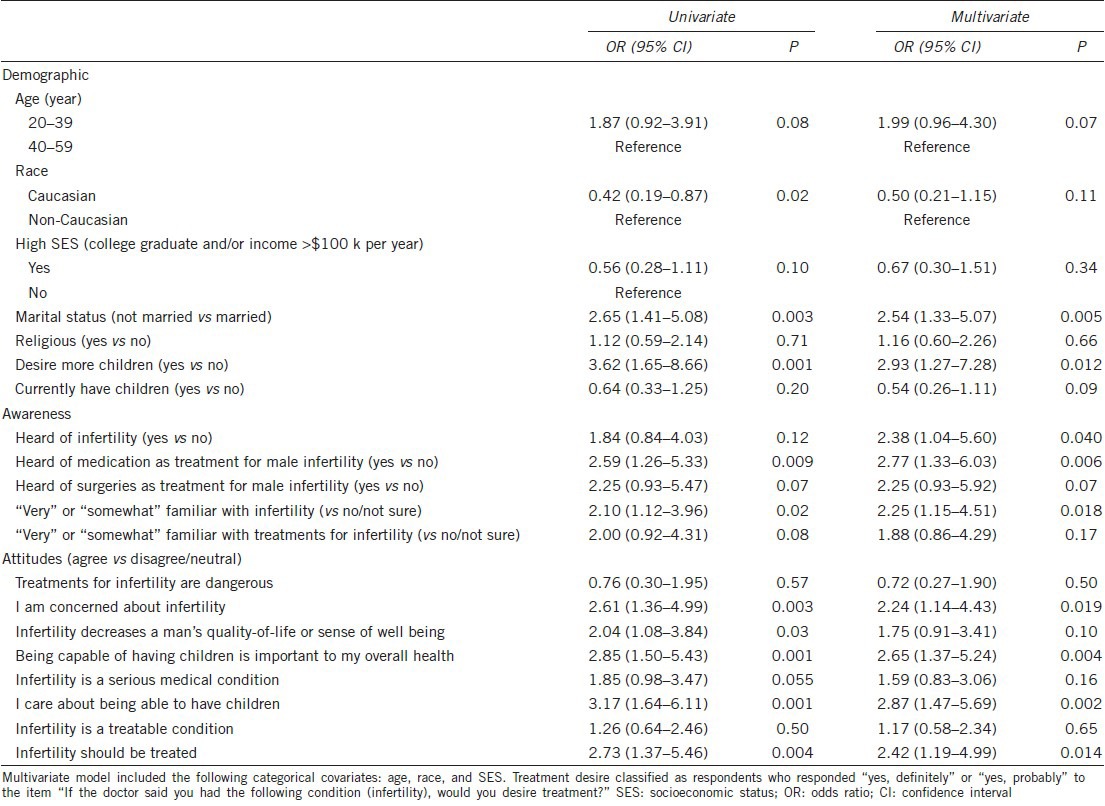

We examined demographic, awareness and attitude items as predictors of treatment desire among men under the age of 60 years (n = 161), since it was assumed that men over 60 will likely not desire more children. Of these men, when asked if they would desire treatment for infertility if the doctor said they had infertility, 34% responded “yes, definitely,” 22% “yes, probably,” 14% “not sure,” 17% “no, probably not,” 13% “no, definitely not.” Those who responded “yes, definitely” and “yes, probably” were considered to desire treatment.

Two demographic items were significant predictors of treatment desire on both unadjusted and adjusted analyses (Table 4). The strongest demographic predictor of desire for treatment included currently desiring more children, compared with men who did not want children (OR: 3.62, 95% CI: 1.65–8.66, P = 0.001). Men who were not married (vs married) were also more likely to desire treatment (OR: 2.65, 95% CI: 1.41–5.08, P = 0.0025). Age (20–39 vs 40–59), race, and SES were not significant predictors on the adjusted analyses, however non-Caucasian men were more likely to desire treatment on unadjusted analyses.

Table 4.

Factors associated with desire for treatment among men under 60 years of age (n=161)

A majority of awareness and attitude items were statistically significant predictors of treatment desire on both unadjusted and adjusted analyses. In multivariate analysis, the following awareness items were predictors of desire for treatment: being very or somewhat familiar with infertility (OR: 2.25, 95% CI: 1.15–4.51), having heard of the condition (OR: 2.38, 95% CI: 1.04–5.60) and having knowledge of medication being a treatment for male infertility (OR: 2.77, 95% CI: 1.33–6.03). Agreeing with the following attitude statements (vs disagree/neutral) were also significant predictors of treatment desire: “I am concerned about infertility” (OR: 2.24, 95% CI: 1.14–4.43), “being capable of having children is important to my overall health (OR: 2.65, 95% CI: 1.37–5.24), “I care about being able to have children” (OR: 2.87, 95% CI: 1.47–5.69) and “infertility should be treated” (OR: 2.42, 95% CI: 1.19–4.99).

DISCUSSION

Attitudes of and awareness toward medical conditions and their treatment are significant contributors to health-seeking behavior14 and possible determinants of health disparities. We sought to examine these factors as related specifically to infertility in a diverse group of men in the primary care setting. Overall, awareness of male infertility and its treatment was found to be poor with a substantial number of responders indicating that they were not familiar with the condition or had not heard of treatment options for its management. However, when queried about concern about infertility, most participants agreed that it is a serious, but treatable, medical condition. Only a few men believed treatments for infertility were dangerous. Familiarity with the condition and its treatments were significant predictors of treatment desire. Several attitude items were also associated with desire for treatment including the belief that infertility decreases a man's quality-of-life and that the condition should be treated. Race and SES, however, were not significant predictors of desire for treatment. Overall, men had greater awareness of treatments for female infertility, with 35% indicating they had heard of surgery and 46% had heard of medication as treatment for infertile women.

High SES, but not race, was significantly associated with greater awareness of infertility. On multivariate analysis, the odds of having heard of infertility was over 4 times higher, and the odds of being somewhat/very familiar with infertility was nearly 3 times higher in men of high SES (vs the rest of the cohort). Lack of awareness among men of lower SES in our study is consistent with previously-described disparities in infertility treatment. In their study Smith et al.5 found that household income and education were important predictors of those using fertility treatments and proposed several explanations for their findings, including knowledge of health care options and cultural differences in the acceptance of specific fertility treatments. A telephone survey of nearly 2000 unmarried men and women aged 18–29 found that 13% of men and 19% of women believed that they were “very likely” to be infertile.15 About 20% of African American and Hispanic men and <10% of Caucasian men in the sample believed they were infertile. Although it is possible that some of the respondents in were indeed infertile, the important contribution of this study is that it highlights the general lack of knowledge about infertility and potential racial variation in the level of awareness.

Our study has shown that several attitude items were significantly associated with race even after adjusting for SES. Non-Caucasian race (vs Caucasian) was associated with being concerned about the condition and that infertility decreases a man's quality-of-life. A recent paper examining data from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth found that African American men were significantly more likely to indicate that being infertile would bother them “a great deal” than Caucasian men were.16 Our survey also found that non-Caucasian participants were significantly more likely to agree with the statements “I am concerned about infertility” and “infertility decreases a man's quality-of-life” than their Caucasian counterparts. This observation appears to indicate that infertility may be particularly burdensome for non-Caucasian. Thus, it is particularly troublesome that disadvantaged racial minorities are less likely to receive treatment for infertility. For example, Jain6 found that even in states in the United States with mandated insurance coverage of infertility treatment, African American women tended to wait longer before seeking infertility treatments than Caucasian. There are certainly several contributing factors to this observation; however, our data suggest that differences in awareness and attitudes are unlikely to explain racial disparities in infertility treatment. For this reason, other factors including cost, access to care, and provider's cultural competence should be examined.

The interpretation of our results warrants caution because of the modest study size, which limits statistical power. In the addition, the clinic-based, rather than population-based, recruitment of participants may affect the generalization of our findings. On the other hand, the main strengths of our study include the racial and socioeconomic diversity of the population and the use of men in a general medical practice, as opposed to specialized fertility-clinic setting. Of course, interest in this topic would be significantly higher in an infertility clinic.

CONCLUSIONS

Patient factors such as attitudes and awareness are one of many possible determinants of health disparities. Our findings suggest that racial disparities in the treatment of infertility may are not explained by negative attitudes or a lack of awareness. However, in socioeconomic disparities, lack of awareness but not attitudes may be a contributing factor. Future research should be aimed at understanding further the determinants of disparities with particular focus on modifiable factors. As recently proposed elsewhere,17 other contributors to disparities include health care system factors (cost, access to care, organizational characteristics, and complexity of clinic operations), provider factors (bias and stereotyping, competing demands), the clinical encounter (provider communication, cultural competence) and additional patient factors such as preferences and knowledge. As infertility and its treatment involve both men and women, additional research should focus on awareness of and attitudes towards this condition in couples rather than individuals.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

RSG conceived of this study, collected data, and performed data analysis, and prepared the manuscript. CWMR conceived of this study. MG performed data analysis and prepared the manuscript. DV collected data. WH conceived of this study and performed data analysis, and prepared the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Part of this research was supported by unrestricted educational grants from the Parker-Fraser Foundation and the Robert A. and Mary P. Daniels Family Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chandra A, Stephen EH. Impaired fecundity in the United States: 1982-1995. Fam Plann Perspect. 1998;30:34–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stephen EH, Chandra A. Declining estimates of infertility in the United States: 1982-2002. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:516–23. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.02.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandra A, Martinez GM, Mosher WD, Abma JC, Jones J. Fertility, Family Planning, and Reproductive Health of U.S. Women: data from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Vital and Health Statistics Series 23, Data from the National Survey of Family Growth Vital Health Statistics. 2005:1–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wellons MF, Fujimoto VY, Baker VL, Barrington DS, Broomfield D, et al. Race matters: a systematic review of racial/ethnic disparity in Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology reported outcomes. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:406–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith JF, Eisenberg ML, Glidden D, Millstein SG, Cedars M, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in the use and success of fertility treatments: analysis of data from a prospective cohort in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.04.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jain T. Socioeconomic and racial disparities among infertility patients seeking care. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:876–81. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.07.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simmons FA. Human infertility. N Engl J Med. 1956;255:1186–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195612202552505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thonneau P, Marchand S, Tallec A, Ferial ML, Ducot B, et al. Incidence and main causes of infertility in a resident population (1,850,000) of three French regions (1988-1989) Hum Reprod. 1991;6:811–6. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson JE, Farr SL, Jamieson DJ, Warner L, Macaluso M. Infertility services reported by men in the United States: National Survey data. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:2466–70. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eisenberg ML, Lathi RB, Baker VL, Westphal LM, Milki AA, et al. Frequency of the male infertility evaluation: data from the National Survey of Family Growth. J Urol. 2013;189:1030–4. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.08.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Diagnostic evaluation of the infertile female: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:302–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Diagnostic evaluation of the infertile male: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Missmer SA, Seifer DB, Jain T. Cultural factors contributing to health care disparities among patients with infertility in Midwestern United States. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:1943–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Polis CB, Zabin LS. Missed conceptions or misconceptions: perceived infertility among unmarried young adults in the United States. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2012;44:30–8. doi: 10.1363/4403012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sherrod RA, DeCoster J. Male infertility: an exploratory comparison of African American and white men. J Cult Divers. 2011;18:29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kilbourne AM, Switzer G, Hyman K, Crowley-Matoka M, Fine MJ. Advancing health disparities research within the health care system: a conceptual framework. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:2113–21. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.077628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]