Abstract

Background

To date, no therapeutic option has been established for sudden deafness refractory to systemic corticosteroids. This study aimed to examine the efficacy and safety of topical insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) therapy in comparison to intratympanic corticosteroid therapy.

Methods

We randomly assigned patients with sudden deafness refractory to systemic corticosteroids to receive either gelatin hydrogels impregnated with IGF-1 in the middle ear (62 patients) or four intratympanic injections with dexamethasone (Dex; 58 patients). The primary outcome was the proportion of patients showing hearing improvement (10 decibels or greater in pure-tone average hearing thresholds) 8 weeks after treatment. The secondary outcomes included the change in pure-tone average hearing thresholds over time and the incidence of adverse events.

Results

In the IGF-1 group, 66.7% (95% confidence interval [CI], 52.9–78.6%) of the patients showed hearing improvement compared to 53.6% (95% CI, 39.7–67.0%) of the patients in the Dex group (P = 0.109). The difference in changes in pure-tone average hearing thresholds over time between the two treatments was statistically significant (P = 0.003). No serious adverse events were observed in either treatment group. Tympanic membrane perforation did not persist in any patient in the IGF-1 group, but did persist in 15.5% (95% CI, 7.3–27.4%) of the patients in the Dex group (P = 0.001).

Conclusions

The positive effect of topical IGF-1 application on hearing levels and its favorable safety profile suggest utility for topical IGF-1 therapy in patients with sudden deafness.

Trial registration

UMIN Clinical Trials Registry Number UMIN000004366, October 30th, 2010.

Keywords: Dexamethasone, Drug delivery system, IGF-1, Local application, Sudden sensorineural hearing loss

Background

Sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSHL), an unexplained unilateral hearing loss with an onset of less than 72 h, is a common disease with acute onset hearing impairment. The incidence of SSHL is reportedly 5 to 20 patients per 100,000 persons per year [1]. Approximately 35,000 patients with SSHL consult a doctor each year in Japan [2]. The standard treatment for SSHL is systemic corticosteroid treatment [3,4]. Hearing improvement after systemic corticosteroids occurs in 50% of the patients, but approximately 20% of the patients show no response [5]. Further, systemic corticosteroid treatment often causes adverse events [6] that can occasionally be life-threatening [7]. As an alternative for systemic corticosteroids, intratympanic corticosteroid treatment by direct injection into the middle ear has recently gained wide popularity because of the low risk for systemic adverse events and because of the potential delivery of high concentrations of a corticosteroid into the inner ear [8]. Intratympanic corticosteroid therapy is commonly used for the treatment of SSHL, after the failure of systemic corticosteroid treatment [9-15]. However, the supporting evidence for its use is weak because of the limitation in the study design and power [16].

A major difficulty in treating sensorineural hearing loss is the poor regeneration capacity of the mammalian cochlea. Therefore, protecting the cochlea from irreversible degeneration is a practical strategy. Several growth factors have been investigated for their protective effects on the sensory hair cells of the cochlea [17,18]. The focus of this study was on insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), which has been used for the treatment of insulin-resistant diabetes and dwarfism. IGF-1 also plays crucial roles in both the development and maintenance of the cochlea [19,20]. We used a gelatin hydrogel, which enables the sustained release of proteins or peptides, for the delivery of IGF-1 into the cochlear fluid [21]. We previously performed a successful series of animal experiments using this method [21,22]. A prospective, single-armed clinical trial in patients with SSHL refractory to systemic corticosteroids was then performed, the results of which indicated the safety and efficacy of topical IGF-1 therapy in comparison to the historical control of hyperbaric oxygen therapy [23].

The goal of the current study was to investigate the efficacy and safety of topical IGF-1 therapy as a novel therapeutic option for SSHL. We conducted a multicenter, randomized clinical trial to compare topical IGF-1 therapy and intratympanic corticosteroid therapy for treating SSHL refractory to systemic corticosteroids.

Methods

Study design and patients

This was a multicenter, randomized, open, parallel-group trial. The study was conducted from November 2010 through October 2013 at 9 tertiary referral hospitals in Japan. The trial followed the guiding principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol, manual of procedures, and informed consent form were approved by the institutional review boards of all participating sites (Ethical Committee of the Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University [C470], Ethical Committee of the Graduate School of Medicine, Hirosaki University [2011–145], Ethical Committee of University of Tsukuba Hospital [H23-13], Ethical Committee of Toranomon Hospital [2011-4-15], Ethical Committee of Shinshu University Hospital [1705], Ethical Committee of Nagoya City University Hospital [45-11-0005], Ethical Committee of Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital [1], Ethical Committee of Ehime University Hospital [1105003], and Ethical Committee of the Graduate School of Medicine, Kyushu University [23011]). All patients provided written informed consent. Eligible participants were all adults, 20 years or older, who had SSHL defined as a unilateral sensorineural hearing loss of at least 30 decibels (dB) sound pressure level (SPL) over at least three test frequencies that developed within 3 days. They also met the following eligibility criteria: they had been diagnosed as having SSHL within 25 days of onset; they presented with an abnormality in the distortion product of otoacoustic emissions; and they showed less than 30 dB hearing improvement in the mean hearing level, based on pure-tone audiometry (PTA) at five tested frequencies (0.25 kHz, 0.5 kHz, 1.0 kHz, 2.0 kHz, and 4.0 kHz) after more than 7 days of systemic corticosteroid treatment. Similar to our previous trial [23], we excluded patients with active chronic otitis media, acute otitis media, otitis media with effusion or dysfunction of the auditory tube, malignant tumors, and systemic diseases. All patients underwent imaging examinations to rule out retrocochlear pathology.

Randomization and masking

Patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive either topical IGF-1 therapy or intratympanic dexamethasone (Dex) therapy. Randomization was performed centrally with stratification by the study sites and the mean hearing thresholds, based on the PTA at the five frequencies tested at registration (lower than 90 dB SPL vs. 90 dB SPL or higher). The randomization sequence was generated by a third-party contract clinical research organization (independent from the trial investigators). Local investigators used a web-based system during enrolment, which then automatically assigned patients to either treatment group. Besides central randomization, no further masking was used in this open-label study.

Procedures

The treatment was performed within 7 days of enrolment and systemic corticosteroid treatment was completed by the time of enrolment. Gelatin hydrogels were produced from porcine skin gelatin (Nitta Gelatin Inc., Osaka, Japan), based on a previously described method [23,24]. Mecasermin (Somazon [10 mg for injection]; Astellas Pharma, Inc., Tokyo, Japan), a recombinant human IGF-1, was dissolved in physiological saline at a final concentration of 10 mg/mL. Sixty minutes before application, a 30 μL sample of mecasermin solution was mixed with 3 mg of gelatin hydrogel. After tympanostomy under local anesthesia with 1% lidocaine, the hydrogel (which contained 300 μg of mecasermin) was placed in the round window niche of the middle ear; a single application was used. The control group received four 0.5 mL doses containing 3.8 mg/mL dexamethasone sodium phosphate (Orgadrone injection [1.9 mg]; MSD, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) that was injected into the middle ear through the tympanic membrane. In the literature [9-15], a variety of regimens for intratympanic injections of corticosteroids have been used. Considering practical use in common clinical settings, we chose four doses. Injections were performed over 4 consecutive days in principle. Within at least 7 days, four injections were administered. Patients were placed in the supine position with the affected ear slightly raised and remained in this position for 30 min after the injection. For 16 weeks after treatment, the patients were examined at the outpatient clinics of the participating sites. The PTA was measured on the day of enrolment, and then at 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks after treatment. During the observation period, which totaled 16 weeks, all adverse events were recorded.

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure was the proportion of patients showing hearing improvement of 10 dB or greater in the mean hearing level. Hearing improvement was based on PTA at five tested frequencies and was defined as better than slight recovery, based on the criteria for hearing improvement determined by the Sudden Deafness Research Committee of the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare in 1984 (Table 1) at 8 weeks after treatment. Briefly, the complete recovery includes patients showing recovery of a hearing level within 20 dB SPL or to the similar level to the opposite side, the marked recovery is more than 30 dB recovery, and the no recovery is less recovery than 10 dB. Secondary outcome measures included the change in the pure-tone average hearing thresholds over time (i.e., from the first audiogram to the 16-week follow-up audiogram), the proportion of patients showing hearing improvement at 12 and 16 weeks after treatment, and the incidence of adverse events during the observation period. In addition to checking vital signs in the physical examination at each visit, laboratory studies were performed at registration, and then at 1 week, 8 weeks, and 16 weeks after treatment.

Table 1.

Criteria for hearing improvement determined by Sudden Deafness Research Committee of the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in 1984

| Complete recovery | Recovery of a hearing level within 20 decibels (dB) at all five frequencies tested (0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 and 4.0 kHz) or recovery to the same level as the opposite side in pure-tone auditometry |

| Marked recovery | 30 dB and over recovery in the mean hearing level at the five frequencies tested |

| Slight recovery | Recovery of better than 10 dB and less than 30 dB in the mean hearing level at the five frequencies tested |

| No response | Less recovery than 10 dB in the mean hearing level at the five frequencies tested |

Statistical analysis

The null hypothesis was that the effect of topical IGF-1 treatment on the proportion of patients showing hearing improvement would not be superior to intratympanic injection of Dex. The sample size was determined based on our previous findings and on published papers. In our previous clinical trial of topical IGF-1 therapy, no patient that had been enrolled later than 26 days after sudden hearing loss recovered their hearing [23]. The proportion of patients with hearing improvement after topical IGF-1 treatment was 62.5% (10 of 16 patients) at 12 weeks and 68.8% (11 of 16 patients) at 24 weeks, using the eligibility criteria of patients with SSHL within 25 days after onset of sudden hearing loss. Based on these findings, we hypothesized that the expected proportion of patients showing hearing improvement with topical IGF-1 therapy would be 65%. To determine the expected proportion of patients showing hearing improvement for intratympanic Dex therapy, we referred to the information in several publications [9-15] that were available in October 2010 and used the following criteria: i) the sample size had more than 10 participants and ii) intratympanic Dex therapy was a salvage treatment (Table 2). In these previous reports, the mean proportion of patients showing hearing improvement was 39% (range, 21–58%). Therefore, the proportion of patients who would show hearing improvement with intratympanic Dex therapy was expected to be approximately 40%. The sample size was based on the continuity-adjusted arcsine test with a one-sided significance level of 0.05 and a power of 0.80. The required sample size was 120 participants, assuming that 5% of the patients would be excluded from the analysis.

Table 2.

Previous studies of intratympanic dexamethasone therapy as a salvage treatment

| No. of patients | PTA recovery | Dexamethasone concentration | Doses | Proportion of recovery (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ho et al. [9] | 15 | 28 dB | 4 mg/mL | 3 doses, once a week | 53% |

| Choung et al. [10] | 34 | 9 dB | 5 mg/mL | 4 doses, twice a week | 39% |

| Roebuck et al. [11] | 31 | 12 dB | 24 mg/mL | Single | 29% |

| Haynes et al. [12] | 40 | 5 dB | 24 mg/mL | Single | 27.5% |

| Plontke et al. [13] | 11 | 14 dB | 4 mg/mL | Pump for 14 days | 45% |

| Kakehata et al. [14] | 24 | 17 dB | 4 mg/mL | 15 doses | 58% |

| Lee et al. [15] | 34 | NA | 4 mg/mL | 6 doses for 14 days | 21% |

| Mean (95% CI) | 27 (21–33) | 39% (30%–48%) |

PTA, Pure-tone audiometry; NA, Not available; CI, Confidential interval.

All statistical analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat basis. The safety analyses were conducted on all patients who underwent randomization and received at least one dose of the study drugs. Efficacy was analyzed in all patients except those who had been excluded from the safety analyses due to eligibility violations. The differences between treatments in the proportion of patients showing hearing improvement at 8, 12, and 16 weeks after treatment were evaluated with Fisher’s exact test at a one-sided significance of 0.05. The difference between treatments in changes in pure-tone average hearing thresholds over time was investigated with repeated measures linear mixed model containing terms for treatment, time, and treatment-by-time interaction with an unstructured covariance structure [25]. The effect of treatment-by-treatment interaction was analyzed with the t-test at a one-sided significance of 0.05. The differences between treatments in the incidence of adverse events and in the baseline characteristics were analyzed with either Fisher’s exact test or the t-test at a two-sided significance of 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed by using SAS version 9.3 software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Study overview

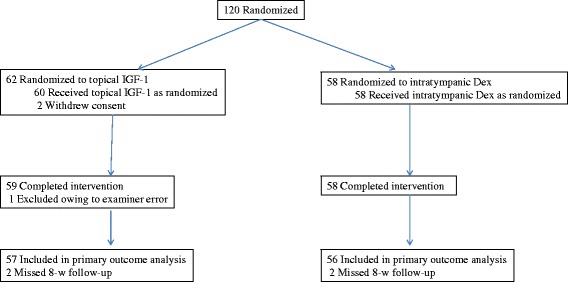

Patients from nine participating sites were enrolled between March 2011 and October 2013. The recruitment and enrollment period was originally planned to close in February 2013, but it was extended to meet the recruitment targets. There were 120 patients who consented to participate (Figure 1). All patients were randomized to either the IGF-1 group or the Dex group; 118 patients were included in the safety analysis (60 IGF-1, 58 Dex) because 2 patients from the IGF-1 group withdrew consent. Of the 118 patients who were included, 4 patients completed the treatments, but missed the 8-week follow-up (2 IGF-1, 2 Dex) and 1 patient was excluded owing to examiner error (1 IGF-1).

Figure 1.

Study overview.

Baseline characteristics were comparable between the two treatment groups (Table 3). Between the IGF-1 and Dex groups, no significant baseline differences in demographics, physical characteristics, ear examination, or PTA thresholds were found except the proportion of patients presenting with aural fullness (Table 3). The mean age of all participants was 49.3 years, and 45.8% of the participants were male. The mean PTA thresholds in the affected and unaffected ears were 85.2 dB SPL (95% confidence interval [CI], 81.3–89.1) and 18.1 dB SPL (95% CI, 14.9–21.3), respectively. The mean number of days from symptom onset to study entry was 16.0 days (95% CI, 15.2–16.9). At enrolment, dizziness or vertigo was present in 45.8% of the patients, tinnitus was present in 84.8% of the patients, and aural fullness was present 64.4% of the patients.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of patients

| Characteristics | Intratympanic Dex (n = 58) | Topical IGF-1 (n = 60) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age-yr, mean ± SD | 50.1 ± 13.0 | 48.6 ± 14.0 | 0.557 |

| Male sex-no. (%) | 26 (44.8) | 28 (46.7) | 0.855 |

| No. of days for study entry from onset, mean (95% CI) | 16.3 (15.1–17.5) | 15.8 (14.6–17.0) | 0.574 |

| Hearing improvement by pre-treatment-no. (%) | |||

| >10 dB, <30 dB | 13 (22.4) | 17 (28.3) | 0.528 |

| <10 dB | 45 (77.6) | 43 (71.7) | |

| Hearing-dB pure-tone average, mean (95% CI) | |||

| Affected ear | 84.8 (79.1–90.4) | 85.6 (80.0–91.2) | 0.835 |

| Unaffected ear | 15.8 (12.4–19.2) | 20.4 (15.0–25.7) | 0.160 |

| Other symptoms-no. (%) | |||

| Dizziness/Vertigo | 23 (39.7) | 31 (51.7) | 0.202 |

| Tinnitus | 49 (84.5) | 51 (85) | >0.999 |

| Aural fullness | 44 (75.9) | 32 (53.3) | 0.013* |

An asterisk indicates statistical significance with Fisher’s exact test. Dex: dexamethasone.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients showing hearing improvement (10 dB or greater in pure-tone average hearing thresholds) at 8 weeks after treatment. In the Dex group, 53.6% (95% CI, 39.7–67.0%) of patients showed hearing improvement at 8 weeks after treatment, whereas in the IGF-1 group, 66.7% (95% CI, 52.9–78.6%) of patients showed hearing improvement (Table 4). The null hypothesis for the primary outcome was not rejected (P = 0.109). However, a trend was observed in the higher proportion of patients in the IGF-1 group showing complete or marked recovery (30 dB or greater in pure-tone average hearing thresholds) over that in the Dex group (Table 2).

Table 4.

Primary and secondary outcomes

| Intratympanic Dex | Topical IGF-1 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |||

| Proportion of patients showing hearing recovery at 8 weeks | 53.6% (30/56) | 66.7% (38/57) | 0.109 |

| [95% CI: 39.7–67.0] | [95% CI: 52.9–8.6] | ||

| Complete recovery | 0.0% (0/56) | 3.5% (2/57) | |

| Marked recovery | 16.1% (9/56) | 24.6% (14/57) | |

| Slight recovery | 37.5% (21/56) | 38.6% (22/57) | |

| No recovery | 46.4% (26/56) | 33.3% (19/57) | |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| Proportion of patients showing hearing recovery at 12 weeks | 55.4% (31/56) | 70.7% (41/58) | 0.066 |

| [95% CI: 41.5–68.7] | [95% CI: 57.3–81.9] | ||

| Complete recovery | 0.0% (0/56) | 5.2% (3/58) | |

| Marked recovery | 21.4% (12/56) | 31.0% (18/58) | |

| Slight recovery | 33.9% (19/56) | 34.5% (20/58) | |

| No recovery | 44.6% (25/56) | 29.3% (17/58) | |

| Proportion of patients showing hearing recovery at 16 weeks | 54.7% (29/53) | 67.9% (36/53) | 0.116 |

| [95% CI: 40.4–68.4] | [95% CI: 53.7–80.1] | ||

| Complete recovery | 0.0% (0/53) | 5.7% (3/53) | |

| Marked recovery | 22.6% (12/53) | 24.5% (13/53) | |

| Slight recovery | 32.1% (17/53) | 37.7% (20/53) | |

| No recovery | 45.3% (24/53) | 32.1% (17/53) | |

| Adverse events | |||

| Serious | 0.0% (0/58) | 0.0% (0/59) | >0.999 |

| Non-serious | 43.1% (25/58) | 35.0% (21/59) | 0.452 |

| Tympanic membrane perforation | 15.5% (9/58) | 0.0% (0/59) | 0.001* |

| Otitis media | 1.7% (1/58) | 6.8% (4/59) | 0.364 |

| Otitis externa | 0.0% (0/58) | 1.7% (1/59) | >0.999 |

| Tinnitus | 8.6% (5/58) | 0.0% (0/59) | 0.027* |

| Nausea/Vomit | 3.4% (2/58) | 3.4% (2/59) | >0.999 |

| Others | 24.1% (14/58) | 30.5% (18/59) | 0.535 |

Asterisks indicate statistical significance with Fisher’s exact test.

Secondary outcomes

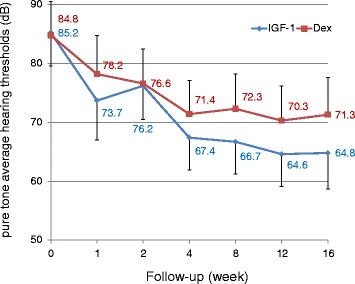

The changes in the pure-tone average hearing thresholds occurring over time in both treatments are shown in Figure 2. The difference in the changes in the pure-tone average hearing thresholds over time between the treatments was statistically significant with repeated measures linear mixed model containing terms for treatment, time, and treatment-by-time interaction with an unstructured covariance structure (the effect for the interaction term [standard error]: −0.28 [0.10], P = 0.003). This demonstrated that pure-tone average hearing thresholds of the IGF-1 group significantly reduced over time, if changes in pure-tone average hearing thresholds over time in the Dex group were set to zero.

Figure 2.

Changes in pure-tone average hearing thresholds over time. The difference between IGF-1 and dexamethasone (Dex) treatments in changes in pure-tone average hearing thresholds over time was statistically significant. Captions in the graph show mean values. Bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

The proportions of patients showing hearing improvement (i.e., 10 dB or greater) at 12 weeks and 16 weeks after treatment were estimated as the secondary outcomes (Table 4). The null hypothesis for the proportions of patients showing hearing improvement at 12 weeks or 16 weeks after treatment was not rejected (P = 0.066 for 12 weeks; P = 0.116 for 16 weeks). At 12 and 16 weeks after treatment, there was a trend in the IGF-1 group showing a larger number of patients with complete and marked recovery when compared to the Dex group (Table 4).

Adverse events

No serious adverse events were observed in either treatment group. During the observation period, moderate adverse events occurred in 43.1% (95% CI, 30.2–56.8) of the patients in the Dex group and in 35.0% (95% CI, 23.1–48.4) of the patients in the IGF-1 group (Table 4). No significant difference in the incidence of adverse events was found between treatments (P = 0.452). Most adverse events, such as otitis media, otitis externa, tinnitus, and nausea or vomiting disappeared during the observation period. However, tympanic membrane perforation persisted in 15.5% (95% CI, 7.3–27.4%) of the patients in the Dex group at the end of the observation period. On the other hand, no patient in the IGF-1 group showed residual perforation in the tympanic membrane. The difference in the incidence of tympanic membrane perforation was statistically significant (P = 0.001).

Discussion

This is the first randomized controlled clinical trial to test the efficacy of a growth factor for the treatment of sensorineural hearing loss. In the current study, we locally applied IGF-1 to patients with SSHL refractory to systemic steroids. The null hypothesis of the primary outcome was that the proportion of patients showing hearing improvement after topical IGF-1 therapy would not be better than that after intratympanic Dex therapy. The null hypothesis was not rejected in the present study. The major reason for this is an unexpectedly high proportion of patients showing hearing improvement after intratympanic Dex therapy. The proportion of patients showing hearing improvement after topical IGF-1 therapy was 66.7 to 70.7%, which was nearly identical to our hypothesized value of 65%, whereas the proportion of patients showing hearing improvement after intratympanic Dex therapy (range, 53.6– 55.4%) was higher than our hypothesized value of 40%.

Although the null hypothesis for the primary outcome was not rejected, this randomized controlled trial showed significantly better recovery of pure-tone average thresholds over time in the IGF-1 group, compared to the Dex group. In addition, a trend that the proportion of patients in the IGF-1 group who showed complete or marked recovery was higher than that in the Dex group was observed at 8, 12, or 16 weeks after treatment. Complete recovery of hearing was observed only in the IGF-1 group. These findings strongly suggest the superior efficacy of topical IGF-1 therapy over intratympanic Dex therapy.

In the current study, we used intratympanic corticosteroid therapy as a control treatment because it has widely been accepted as a salvage treatment for SSHL refractory to systemic corticosteroids [9-15]. The current randomized study also provided evidence for the safety and efficacy of intratympanic Dex therapy for SSHL refractory to systemic corticosteroids. Similar to the results of previous studies [9-15], no serious adverse events occurred in the Dex patient group. However, tympanic membrane perforation persisted in 15.5% of these patients, while tympanic membrane perforation was absent in the IGF-1 patient group. The incidence of tympanic membrane perforation in the Dex group in the present study was higher than the 3.9% incidence in a previous randomized trial of intratympanic corticosteroid therapy as the initial treatment [8]. This may be because of a difference in either the application regimen or the influence of the preceding systemic corticosteroid treatment. It is important to note that intratympanic injection of corticosteroids causes tympanic membrane perforation in a certain proportion of treated patients, while both our previous [23] and present results demonstrated no occurrence of residual perforation in tympanic membranes of patients treated with topical IGF-1 therapy. This indicated the superior safety of topical IGF-1 therapy over intratympanic Dex therapy. On the other hand, the high incidence of tympanic membrane perforation in the Dex group might affect hearing recovery outcomes in the Dex group.

The present findings indicate the efficacy and safety of topical IGF-1 therapy for SSHL. However, topical IGF-1 therapy requires surgical procedures and causes uncomfortable symptoms associated with the local application. In addition, spontaneous recovery of hearing occurs in 30 to 60% of patients with SSHL [5,26-28]. Therefore, with the need for balancing the harmful side effects and the benefits, SSHL patients showing insufficient hearing improvement after the administration of oral corticosteroids or after strict observation for 7 days may be good candidates for topical IGF-1 therapy. On the other hand, IGF-1 is a promoter of cell proliferation in some cellular contents. Therefore, a long-term follow-up of patients may be required. Of note, in our previous clinical trial, we locally applied IGF-1 in the middle ear of 25 patients with refractory SSHL [23]; in the 5-year follow-up, no tumor formation was identified in those patients.

Conclusions

We performed a randomized, controlled clinical trial of topical IGF-1 therapy in patients with SSHL refractory to systemic corticosteroids and compared this treatment to intratympanic corticosteroid therapy. Present results suggest the possibility that IGF-1 is superior to intratympanic Dex therapy, but the current study design failed to confirm this possibility. The positive effect of topical IGF-1 application on hearing levels and its favorable safety profile suggest utility for topical IGF-1 therapy as a salvage treatment for SSHL.

Acknowledgements

The corresponding and last authors (TN and JI) had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. This study is funded by a Grant-in-Aid for Researches on Sensory and Communicative Disorders from the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare (H21-Kankaku-ippann-006 to TN). We thank all the participating patients and all the otolaryngologists, physicians, statisticians, audiologists, and members of the research staff from Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan: T Okano, R Horie, E Ogino-Nishimura, M Matsunaga, M Yamamoto; Kyoto University Hospital, Kyoto, Japan: A Kinoshita, K Mukai, A Kuroda, M Oka, H Toyokuni; Toranomon Hospital, Tokyo, Japan: N Imai, T Misawa; Shinshu University Hospital, Matsumoto, Japan: K Tsukada, R Kitoh; Ehime University Hospital, Ehime, Japan: K Gyo, M Okada, T Takagi; University of Tsukuba Hospital, Tsukuba, Japan: A Hara, B Nishimura, Y Hirose; Nagoya City University Hospital, Nagoya, Japan: S Murakami, K Kabaya; Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital, Kobe, Japan: Y Naito; Yamagata University Hospital, Yamagata, Japan: S Kakehata; and Kyushu University Hospital, Fukuoka, Japan: N Matsumoto, T Kimitsuki.

Role of the funding source

This work was initiated by the investigators and was conducted independently of any commercial entities. The drugs were purchased commercially.

Abbreviations

- CI

Confidence interval

- dB

Decibels

- Dex

Dexamethasone

- IGF-1

Insulin-like growth factor-1

- PTA

Pure-tone audiometry

- SSHL

Sudden sensorineural hearing loss

Footnotes

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing of interests.

Authors’ contributions

TN obtained funding. TN, ST, HT, TI-I, TI, ASh, AY, YT, and JI contributed to the research design. AY and YT designed and prepared gelatin hydrogels. HT and ASh undertook and monitored study conduct with supervision from TN. JI, TN, KK, SU, NH, KT, MT, KF, ASa, SK, TS, HH, and NY recruited patients and undertook patient treatments. HT performed data cleaning and preparations for analysis. MY performed statistical analyses and wrote the statistical sections. TN and MY interpreted data. TN wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the revised draft versions. All authors approved the final version.

Contributor Information

Takayuki Nakagawa, Email: tnakagawa@ent.kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Kozo Kumakawa, Email: kozo3000@hotmail.com.

Shin-ichi Usami, Email: usami@shinshu-u.ac.jp.

Naohito Hato, Email: nhato@m.ehime-u.ac.jp.

Keiji Tabuchi, Email: ktabuchi@md.tsukuba.ac.jp.

Mariko Takahashi, Email: mari-tk@med.nagoya-cu.ac.jp.

Keizo Fujiwara, Email: fuji_ent@kcho.jp.

Akira Sasaki, Email: akiras@cc.hirosaki-u.ac.jp.

Shizuo Komune, Email: komu@qent.med.kyushu-u.ac.jp.

Tatsunori Sakamoto, Email: sakamoto@ent.kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Harukazu Hiraumi, Email: hhiraumi@ent.kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Norio Yamamoto, Email: yamamoto@ent.kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Shiro Tanaka, Email: shiro@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Harue Tada, Email: haru.ta@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Michio Yamamoto, Email: michyama@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Atsushi Yonezawa, Email: ayone@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Toshiko Ito-Ihara, Email: itoshi@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Takafumi Ikeda, Email: ikeda@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Akira Shimizu, Email: shimizu@virus.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Yasuhiko Tabata, Email: yasuhiko@frontier.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Juichi Ito, Email: ito@ent.kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Byl FM. Sudden hearing loss: eight years’ experience and suggested prognostic table. Laryngoscope. 1984;94:647–661. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198405000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teranishi M, Katayama N, Uchida Y, Tominaga M, Nakashima T. Thirty-year trends in sudden deafness from four nationwide epidemiological surveys in Japan. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127:1259–1265. doi: 10.1080/00016480701242410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rauch SD. Clinical practice. Idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:833–840. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0802129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schreiber BE, Agrup C, Haskard DO, Luxon LM. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Lancet. 2010;375:1203–1211. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson WR, Byl FM, Laird N. The efficacy of steroids in the treatment of idiopathic sudden hearing loss. A double-blind clinical study. Arch Otolaryngol. 1980;106:772–776. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1980.00790360050013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexander TH, Weisman MH, Derebery JM, Espeland MA, Gantz BJ, Gulya AJ, Hammerschlag PE, Hannley M, Hughes GB, Moscicki R, Nelson RA, Niparko JK, Rauch SD, Telian SA, Brookhouser PE, Harris JP. Safety of high-dose corticosteroids for the treatment of autoimmune inner ear disease. Otol Neurotol. 2009;30:443–448. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181a52773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogino-Nishimura E, Nakagawa T, Tateya I, Hiraumi H, Ito J. Systemic steroid application caused sudden death of a patient with sudden deafness. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2013;2013:734131. doi: 10.1155/2013/734131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rauch SD, Halpin CF, Antonelli PJ, Babu S, Carey JP, Gantz BJ, Goebel JA, Hammerschlag PE, Harris JP, Isaacson B, Lee D, Linstrom CJ, Parnes LS, Shi H, Slattery WH, Telian SA, Vrabec JT, Reda DJ. Oral vs intratympanic corticosteroid therapy for idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2011;305:2071–2079. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ho HG, Lin HC, Shu MT, Yang CC, Tsai HT. Effectiveness of intratympanic dexamethasone injection in sudden-deafness patients as salvage treatment. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:1184–1189. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200407000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choung YH, Park K, Shin YR, Cho MJ. Intratympanic dexamethasone injection for refractory sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:747–752. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000205183.29986.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roebuck J, Chang CY. Efficacy of steroid injection on idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135:276–279. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haynes DS, O'Malley M, Cohen S, Watford K, Labadie RF. Intratympanic dexamethasone for sudden sensorineural hearing loss after failure of systemic therapy. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:3–15. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000245058.11866.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plontke S, Löwenheim H, Preyer S, Leins P, Dietz K, Koitschev A, Zimmermann R, Zenner HP. Outcomes research analysis of continuous intratympanic glucocorticoid delivery in patients with acute severe to profound hearing loss: basis for planning randomized controlled trials. Acta Otolaryngol. 2005;125:830–839. doi: 10.1080/00016480510037898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kakehata S, Sasaki A, Futai K, Kitani R, Shinkawa H. Daily short-term intratympanic dexamethasone treatment alone as an initial or salvage treatment for idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Audiol Neurootol. 2011;16:191–197. doi: 10.1159/000320269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee JD, Park MK, Lee CK, Park KH, Lee BD. Intratympanic steroids in severe to profound sudden sensorineural hearing loss as salvage treatment. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;3:122–125. doi: 10.3342/ceo.2010.3.3.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spear SA, Schwartz SR. Intratympanic steroids for sudden sensorineural hearing loss: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145:534–543. doi: 10.1177/0194599811419466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malgrange B, Rigo JM, Van de Water TR, Staecker H, Moonen G, Lefebvre PP. Growth factor therapy to the damaged inner ear: clinical prospects. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1999;49:S19–S25. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5876(99)00126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romand R, Chardin S. Effects of growth factors on the hair cells after ototoxic treatment of the neonatal mammalian cochlea in vitro. Brain Res. 1999;825:46–58. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(99)01211-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonapace G, Concolino D, Formicola S, Strisciuglio P. A novel mutation in a patient with insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) deficiency. J Med Genet. 2003;40:913–917. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.12.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cediel R, Riquelme R, Contreras J, Díaz A, Varela-Nieto I. Sensorineural hearing loss in insulin-like growth factor I-null mice: a new model of human deafness. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:587–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee KY, Nakagawa T, Okano T, Hori R, Ono K, Tabata Y, Lee SH, Ito J. Novel therapy for hearing loss: delivery of insulin-like growth factor 1 to the cochlea using gelatin hydrogel. Otol Neurotol. 2007;28:976–981. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31811f40db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujiwara T, Hato N, Nakagawa T, Tabata Y, Yoshida T, Komobuchi H, Takeda S, Hyodo J, Hakuba N, Gyo K. Insulin-like growth factor 1 treatment via hydrogels rescues cochlear hair cells from ischemic injury. Neuroreport. 2008;19:1585–1588. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328311ca4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakagawa T, Sakamoto T, Hiraumi H, Kikkawa YS, Yamamoto N, Hamaguchi K, Ono K, Yamamoto M, Tabata Y, Teramukai S, Tanaka S, Tada H, Onodera R, Yonezawa A, Inui K, Ito J. Topical insulin-like growth factor 1 treatment using gelatin hydrogels for glucocorticoid-resistant sudden sensorineural hearing loss: a prospective clinical trial. BMC Med. 2010;8:76. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marui A, Tabata Y, Kojima S, Yamamoto M, Tambara K, Nishina T, Saji Y, Inui K, Hashida T, Yokoyama S, Onodera R, Ikeda T, Fukushima M, Komeda M. A novel approach to therapeutic angiogenesis for patients with critical limb ischemia by sustained release of basic fibroblast growth factor using biodegradable gelatin hydrogel: an initial report of the phase I-IIa study. Circ J. 2007;71:1181–1186. doi: 10.1253/circj.71.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cnaan A, Laird NM, Slasor P. Using the general linear mixed model to analyse unbalanced repeated measures and longitudinal data. Stat Med. 1997;16:2349–2380. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19971030)16:20<2349::AID-SIM667>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nosrati-Zarenoe R, Hultcrantz E. Corticosteroid treatment of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss: randomized triple-blind placebo-controlled trial. Otol Neurotol. 2012;33:523–531. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31824b78da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mattox DE, Simmons FB. Natural history of sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1977;86:463–480. doi: 10.1177/000348947708600406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Filipo R, Attanasio G, Russo FY, Viccaro M, Mancini P, Covelli E. Intratympanic steroid therapy in moderate sudden hearing loss: a randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:774–778. doi: 10.1002/lary.23678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]