Abstract

Background:

Cigarettes smoking is a common mode of consuming tobacco in India. This habit usually starts in adolescence and tracks across the life course. Interventions like building decision making skills and resisting negative influences are effective in reducing the initiation and level of tobacco use.

Aims and Objectives:

The purpose of this study was to assess the prevalence of adolescent current cigarette smoking behavior and to investigate the individual and social factors, which influence them both to and not to smoke.

Methodology:

A cross-sectional study was carried out among school going adolescents in Shimla town of North India. After obtaining their written informed consent, a questionnaire was administered.

Results:

The overall prevalence of current cigarette smoking was 11.8%. The binary logistic regression model revealed that parents’ and peers’ smoking behavior influence adolescent smoking behavior. Individual self-harm tendency also significantly predicted cigarette smoking behavior. Parental active participation in keeping a track of their children's free time activities predicted to protect adolescents from taking this habit.

Conclusion:

Our research lends support to the need for intervention on restricting adolescents from taking up this habit and becoming another tobacco industries’ addicted customer. Parents who smoke should quit this habit, which will not only restore their own health, but also protect their children. All parents should be counseled to carefully observe their children's free time activities.

Keywords: Adolescent, smoking, social environment

Introduction

Tobacco smoking is the biggest public health threat of the current era. Worldwide, smoking-related diseases kill an estimated 4 million people every year. This number is predicted to rise to a staggering 10 million a year over the next two decades. There is an overwhelming body of evidence of increased cancer risk in cigarette smokers.[1,2]

Adolescence is a developmental period where behavior is influenced by emotional and social functions. Tobacco companies use sophisticated marketing campaigns to attract people to initiate this habit early. This is precisely based on the premise that, an adolescent once initiated into tobacco use will continue using it lifelong, with very low quit rates. For the tobacco companies, this translates into lifetime revenues, while on the contrary for adolescents it leads to chronic illnesses later in life.[3,4] The rate of adolescent addiction to cigarettes is high in India. According to Global Adult Tobacco Survey 2009, India, more than half of the smokers initiate smoking in their adolescence.[5]

Effort to prevent adolescent smoking focuses on building their individual resistance to social influences.[6] The current study aimed to assess the prevalence of current adolescent cigarette smoking and to investigate the individual and social factors, which influence them both to and not to smoke.

Methodology

A cross-sectional study was conducted among school going adolescents of Shimla town, capital city of Himachal Pradesh. This town has ten government senior secondary schools. The study was conducted during the period from September 2012 to November 2013. In the absence of previous data on cigarette smoking among adolescents in the study area, an estimated prevalence of 50% was used to arrive at the sample size of 384 (n = [1.96]2 × 0.50 × 0.50/[0.05]2) considering 95% confidence level and ±0.5 precision. In order to compensate for design defect, the required sample was multiplied by 2. For student nonresponse/absenteeism the sample size was a further increase by 20%. Thus, the final arrived sample size was 720.

Stratified cluster sampling was used to draw a representative sample of students from grades 9th, 10th, 11th and 12th of the schools. Each class room was considered to be a cluster (38 clusters in 10 schools). From these, 21 classes (primary sampling unit) were selected through probability proportionate to size sampling. In each class, 36 students were selected using simple random sampling to obtain the sample size of 720.

Current cigarette smoker was defined as a student who had smoked cigarettes on one or more days in the preceding month (30 days) of the survey. The individual factors included questions on “feeling sad”, self-body image consciousness”, and “self-harm”. The social factors, included questions on family (sample question: “Do your parents know what you are doing in the free time”) friends (sample question: “Do your friends smoke?”) and school environment (sample question: “Are you happy regarding school relation with your teacher”).

Formal approval was obtained from the State Education Department of Himachal Pradesh and Principals of the selected schools. Informed written consent was obtained from all the study participants and their parents/guardians. Collected data was analyzed using Epi-info software 6.04 for DOS (Centre for Disease Control, Atlanta). Possible predictors of adolescent smoking behaviors’ were identified using a logistic regression model.

Results

The study sample consists of 720 adolescents of which 367 (51%) were males and 353 (49%) were females. Overall, 216 (30%) were enrolled in 9th grade, 216 (30%) in 10th grade, 144 (20%) in 11th grade and 144 (20%) in 12th grade respectively. The mean age of the study population was 15.4 years (standard deviation [SD] =1.4 years).

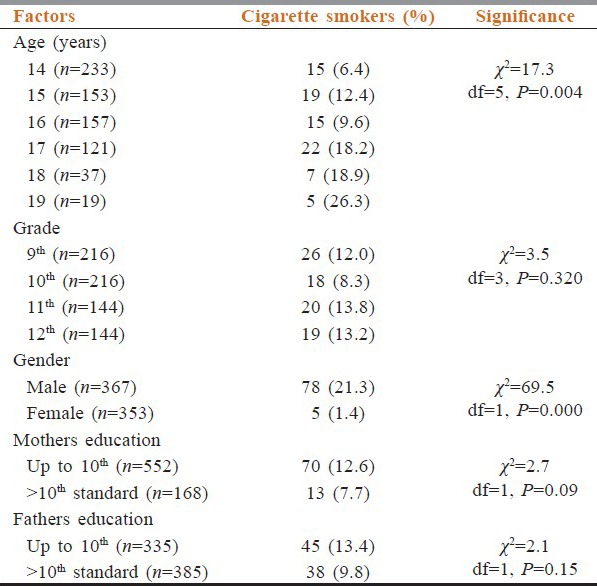

Eighty-three out of 720 students (11.8%) were currently smoking cigarettes. The mean age of initiation of smoking was 13.4 years (SD = 1.9 years). More adolescent boys (22%) when compared to girls (1%) were cigarette smokers (P < 0.001). With increasing age the prevalence of smoking increased. It was 6.4% in adolescent aged 14 years and increased to 26.3% in adolescents aged 19 years [Table 1].

Table 1.

Sociodemographic correlates of adolescent cigarette smokers in Shimla city of North India

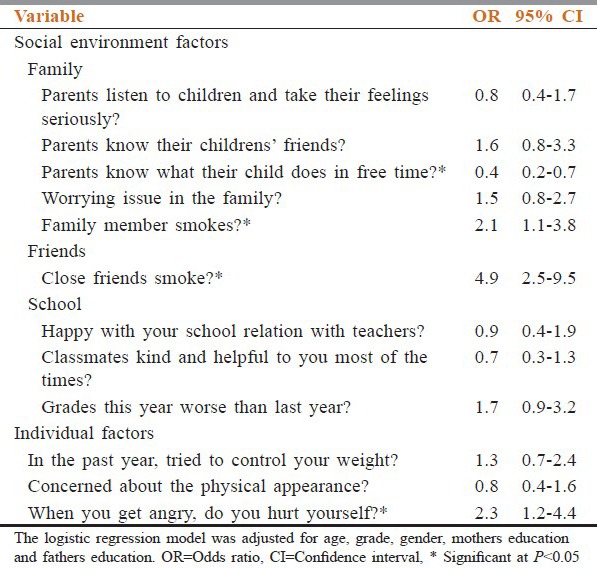

In the binary logistic model, smoking family member (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] =2.1, confidence interval [CI] =1.1-3.8) and smoking friends (AOR = 4.9, CI = 2.5-9.5) and self-harm (AOR = 2.3, CI = 1.2-4.4) were significant risk factors of adolescent smoking behavior. Parental active participation in keeping a track of their children's free time activities can protect adolescents from starting to smoke (AOR = 0.4, CI = 0.2-0.7) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Predictors for cigarette smoking among school going adolescents in Shimla city of North India

Discussion

In this study, the prevalence of current cigarette smoking at 12% was higher against the national average of 6.4% (Global Youth Tobacco Survey [GYTS] India 2009) and the state prevalence of 4% (GYTS Himachal Pradesh 2004).[7,8] The higher prevalence of smoking in our study could be a warning sign of the increasing attitude toward smoking epidemic among adolescents. We observed that the cigarette smoking generally increased with increasing age. The may be explained by the fact that increasing age in the adolescent period is more susceptible to experimentation of risky behaviors like smoking tobacco. Further, in the present study smoking was more among males as compared to females. This observed gender differences can be attributed to societal tolerance attitudes towards male smoking vis-a-vis female smoking in India.

The logistic regression model revealed that having a cigarette smoker at home significantly increased the likelihood of taking up smoking among adolescents. A possible explanation of this may be the fact that adolescents tend to learn by imitation. This tendency means that they will imitate both positive and unhealthy behaviors. Thus, the parental smoking behavior may outweigh adolescent's knowledge of harms of smoking and they resort to this habit. Similar to our observation, studies done by Kelishadi et al. in Iranian adolescents and Shashidhar et al. in Indian adolescents have reported this relationship.[9,10]

Self-harm is primarily a way to cope and deal with feelings that are distressing. In our study we observed that the self-harm tendency was associated with adolescents taking up cigarette smoking behavior. This may precisely be due to the fact that the self-harm experience may generate many difficult feelings and emotions in them like guilt, self-hatred, anger and thus they start smoking. However, eventually this may exacerbate such children's future self-harming behavior. Furthermore, we observed that parental monitoring of child's free time activity was a significant protective factor against adolescent's smoking behavior. Parents thus need to take the responsibility to constantly monitor their children activities and control their whereabouts.[11,12]

A limitation of this study is the use of self-reported survey, which may have resulted in reporting bias. However, the study investigators ensured that privacy of study participants and thus reliability of the responses. Another limitation is related to the cross-sectional design of the study and thus temporality between predictive factors and smoking aspects cannot be assured.

Conclusion

To conclude, the role of parents in fighting this negative habit remains very important. They should motivate their children not to be tempted by peer pressure, educate them of the ill health effects of smoking and monitor their free time activities. All those children whose parents smoke must be an offer to quit and thus become “anti-smoking role models”. Further, smoke free laws in India should be widened beyond their traditional focus on enforcing the ban. As smoking is individual behavior influenced by individual and societal influences, efforts to foster positive long-term interventions focused at the individual, family, and community levels should be the focus of the program and policy makers in India.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Funding from NRHM, Himachal Pradesh, India.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Tobacco free initiative (TFI): Why is tobacco a public health priority? [Last accessed on 2014 Feb 02]. Available from: http://www.who.int/tobacco/health_priority/en .

- 2.Health effects of smoking among young people. [Last accessed on 2014 Jan 26]. Available from: http://www.who.int/tobacco/research/youth/health_effects/en .

- 3.Forman SF, Emans SJ. Current goals for adolescent health care. Hosp Phys. 2000;36:27–42. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neinstein LS. 4th ed. USA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2002. Adolescent Health Care: A Practical Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 5.GATS India report. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. [Last accessed on 2014 Feb 02]. Available from: http://www.mohfw.nic.in/WriteReadData/l892s/1455618937GATS%20India.pdf .

- 6.Cambell TL, Bray JH. The family influence on health. In: Robert ER, editor. Textbook of Family Practice. 6th ed. Pennsylvania: W B Saunders Company; 2002. pp. 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization (SEARO): GYTS fact sheets and reports for India. 2000-2006. [Last accessed on 2014 Feb 02]. Available from: http://www.searo.who.int/en/Section1174/Section2469/Section2480_14169.htm .

- 8.Sinha DN. New Delhi, India: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2006. Tobacco control in schools in India (India Global Youth Tobacco Survey and Global School Personnel Survey, 2006) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelishadi R, Ardalan G, Gheiratmand R, Majdzadeh R, Delavari A, Heshmat R, et al. Smoking behavior and its influencing factors in a national-representative sample of Iranian adolescents: CASPIAN study. Prev Med. 2006;42:423–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shashidhar A, Harish J, Keshavamurthy SR. Adolescent smoking: A study of knowledge, attitude and practice in high school children, pediatric on call child health care. [Last accessed on 2014 Feb 02]. Available from: http://www.pediatriconcall.com/fordoctor/Medical_original_ .

- 11.Reda AA, Moges A, Yazew B, Biadgilign S. Determinants of cigarette smoking among school adolescents in eastern Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Harm Reduct J. 2012;9:39. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-9-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muttappallymyalil J, Divakaran B, Thomas T, Sreedharan J, Haran JC, Thanzeel M. Prevalence of tobacco use among adolescents in north Kerala, India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:5371–4. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.11.5371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]