Abstract

BACKGROUND

Self-inflicted burn injuries carry considerable mortality and morbidity among otherwise fit young individuals. This study assessed the epidemiologic pattern and outcome of these injuries in a burn care facility in Pakistan.

METHODS

The study was carried out at Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences (PIMS) Burn Care Centre in Islamabad over a period of 2 years. It included all adult patients of either gender, aged over 14 years who presented as cases of burn suicides and attempted burn suicides during the study period. Convenience sampling technique was employed. The sociodemographic profile of the patients, motives underlying the act of self-immolation, any underlying psychiatric illness, alcohol abuse, total body surface area (TBSA) burnt, depth of burn injury, associated inhalation injury, duration of hospital stay, and mortality were all recorded.

RESULTS

Seventy five patients (80.64%) were female while 18 patients (19.35%) were male. The overall mean age was 26.89±6.1 years (range=15-52 years). The affected TBSA ranged from 15%-100% with an overall mean of 69.30±25.42%. The hospital stay ranged from 1-37 days with a mean of 7.16±6.60 days. Marital conflicts constituted the most frequent motive underlying the suicidal attempts (n=57; 61.29%) followed by failed love affairs (n=9; 9.67%). There was an overall mortality of 84.95%. The most common sufferers of self inflicted burn injuries were young, married, illiterate housewives who were resident of rural area. Getting marriage was the most common triggering cause for such injuries.

CONCLUSION

There is need to institute appropriate preventive measures to address the issue in a national perspective.

Key Words: Burn, Suicide, Burn, Injury, Pakistan

INTRODUCTION

Burn injury as a major cause of death and disability has a high cost in health care with an increasing trend in mortality and morbidity in patients.1,2 Healing in burn wounds is still a challenge even some medications were introduced in the literature. So every effort is done to provide a shorter in-patient care for burn patients.3 Pseudomonas aeruginosa as an important cause of nosocomial infection may result into septicemia and death in burn patients denoting to its public health importance.4 So it seems that there is a need for burn dressings and more effective therapeutic medications for burn patients. Several products were shown to have therapeutic efficacy and to be with less toxicity when compared with synthetic drugs.5-8

Burn suicide (self-immolation or self-inflicted burns) constitutes one of the most bizarre suicidal approaches that continue to plague humanity even today. Self-immolation represents one extreme of the burn injury spectrum while the other extreme is constituted by assault burn injuries.9-12

Globally, the reported rates of burn suicides vary considerably from country to country and centre to centre. These account for less than 1% of all suicides in high-income countries (such as the United States), however these figures are alarmingly higher in many low and middle income countries like Iran, India, Sri Lanka, Iraq and Afghanistan. Burn suicide accounts for up to 40% of all suicidal deaths in some parts of the developing world and as high as 71% of the suicides in their specific locales.10-20

Generally, the burden of burn injuries is disproportionately shared across the globe with over 95% of burn deaths occurring among the developing nations.21 This imbalance is further compounded by the menace of burn suicide which predominantly affects the developing nations. Overall, burn suicides account for 2-36.6% of all burn injury admissions worldwide.21-24 The present study was carried out to document the prevalent sociodemographic pattern and outcome of self-inflicted burns in our centre at Islamabad, and hence generate evidence base to better address this menace in a national perspective.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This observational study of self-inflicted burns spanned over a period of two years from June 2010 to May 2012. It was carried out at Burn Care Centre of Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences (PIMS) in Islamabad, Pakistan and included all adult patients of either gender, aged over 14 years who presented as cases of burn suicides and attempted burn suicides during the study period.

Convenience sampling technique was employed. Those cases were excluded from the study where either the patient or the accompanying attendants refused to be consent for inclusion in the study. Self-inflicted burn was defined as the purposeful act of self burning with suicidal intention. As the study was an observational one and did not involve any new intervention, it was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975, as revised in 2008 and anonymity of the participants was guaranteed. Informed consent was taken from all the patients or their attendants for inclusion in the study.

Initial assessment and diagnosis of burn injury was made by a thorough history, physical examination and ancillary investigations. The total body surface area (TBSA) of burn was calculated by employing ‘rule of nines’. All the patients were admitted for indoor management. Data collection was performed with the help of a comprehensively designed proforma that encompassed all relevant epidemiologic and clinical variables of interest. The sociodemographic profile of the patients (i.e. age, gender, marital status, educational status, employment status, rural versus urban origin), motives underlying the act of self-burning, any underlying psychiatric illness, alcohol abuse, TBSA burnt, depth of burn injury, associated inhalation injury, duration of hospital stay, and mortality etc. were all recorded on the proforma.

Serial personal interviews with the patient and the accompanying attendants (i.e. spouse, parents, in-laws, siblings, family members and other accompanying supporting neighbors) in separate sessions (through the entire course of management) were carried out to ascertain the circumstances and dynamics surrounding the act of self-burning. The main outcome measures were mortality and length of hospital stay.

As per protocol of our centre, all these patients were managed according to standard management protocols of burn injury. Additionally, the medico-legal issues surrounding the act of burn suicide and attempted burn suicide were dealt with by the medico legal officer of the hospital.

The data were subjected to statistical analysis using statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) (Version 17, Chicago, IL, USA) and various descriptive statistics were employed to calculate frequencies, percentages, means and standard deviation. The numerical data such as age, TBSA burnt and duration of hospitalization were expressed as mean ± standard deviation while the categorical data such as the motives for suicides and various associated risk factors were expressed as frequency and percentages. The percentages were compared by employing Chi-Square test and a P value of less than 0.05 was regarded statistically significant.

RESULTS

During the study period, a total of 93 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Out of these, 75 (80.64%) were females while 18 (19.35%) were males. The age of the patients ranged from 15 to 52 years with an overall mean age of 26.89±6.1 years. The mean age for females was slightly less than that for the males (i.e. 26.26±6.35years versus 29.50±4.4years).

The affected TBSA ranged from 15 to 100% with an overall mean of 69.30±25.42%. The involved TBSA was significantly greater among those who died when compared with those who survived the suicidal attempts (i.e. 76.83±19.25% versus 26.78±7.75%; P<0.05).

The hospital stay ranged from 1-37 days with a mean of 7.16±6.60 days. The hospital stay was significantly shorter among those who died than those who survived. (i.e. 5.31±4.53 days; range= 1-21 days versus 17.57±6.94; range=10-37 days) (P<0.05).

The various sociodemographic and injury characteristics found among the patients were summarized in Table 1. Getting marriage was the most frequent motive underlying the suicidal attempts (n=57; 61.29%) followed by failed love affairs (n=9; 9.67%) as shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

The various sociodemographic and injury characteristics observed among the patients (n=93).

| Variables | Number (%) | P value (%) |

|---|---|---|

| GENDER | ||

| Females | 75 (80.64) | <0.001* |

| Males | 18 (19.35) | |

| AGE | ||

| Upto 35 years | 90 (96.77) | <0.001* |

| >35 years | 3 (3.22) | |

| TBSA burnt | ||

| >50% | 67 (72.04) | <0.001* |

| <50% | 26 (27.95) | |

| Depth of Burn Injury | ||

| Deep | 86 (92.47) | <0.000* |

| Superficial/Mixed | 7 (7.52) | |

| Inhalation Injury | ||

| Present | 59 (63.44) | <0.05* |

| Absent | 34 (36.55) | |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 66 (70.96) | <0.001* |

| Un-married | 23 (24.73) | |

| Widowed/ Divorced | 4 (4.30) | |

| Educational Status | ||

| Illiterate | 79 (84.94) | <0.001* |

| Literate/educated | 14 (15.05) | |

| Employement Status | ||

| Housewife | 58 (62.36) | <0.001* |

| Others | 35 (37.63) | |

| Place of Living | ||

| Rural areas | 86 (92.47) | <0.001* |

| Urban areas | 7 (7.52) | |

Significant P <0.05

Table 2.

Motives triggering burn suicides among the patients (n=93).

| Motives | Number of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Marital conflicts | 57 (61.29) |

| Failed love affairs | 9 (9.67) |

| Political protests | 2 (2.15) |

| Known depression | 1 (1.07) |

| Alcohol use | 1 (1.07) |

| Unknown/ Undisclosed reasons | 23 (24.73) |

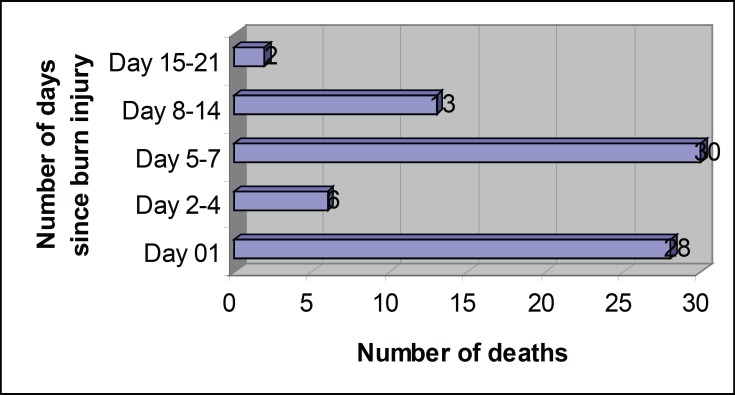

There were 79 deaths accounting for an overall mortality rate of 84.95%. First peak of high number of deaths (n=28; 35.44%) was observed during the first 24 hours, followed by the second high peak in number during 5-7 days after sustaining burn injury (n=30; 37.97%). The time intervals between sustaining burn injury and deaths are shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Number of deaths in relation to the number of days following burn injury (n=79).

DISCUSSION

Self-inflicted burns are prevalent in Pakistan, however there is scarcity of published literature on the issue. Most of the recently published local studies are either focused on the epidemiology of burns in general or pertain to some particular aspect of burn injury management.24-28

Hence our study serves to represent the sociodemographic pattern and outcome of self-inflicted burn injuries in our country. Owing to lack of burn suicides registry in our country, the exact incidence of such injuries is difficult to estimate, however our study with 93 cases over two years period signifies the fact that it is one of our prevalent but neglected medical issues. In our series, the female patients were in overwhelming majority.

Predominant involvement of females in burn suicides is also reported by most of the published studies from developing countries including Iran, India, Sri Lanka, Iraq, Uzbekistan, and Afghanistan.13,16-20,29-35 In sharp contrast to the female predominance in burn suicides in the developing world, studies from the European countries, Australia and North America have reported more frequent involvement of males than females.36,37

In our series, adult females in their second and third decades of life constituted bulk of the patients. This conforms to most of the published studies from countries like Iran, India, and Iraq,11-18,38-40 however Chan et al.41 from Hong Kong, Seoighe et al.42 from Ireland and several other studies from the West and Australia have reported more frequent involvement of higher age groups.43-46 In our series, the bulk of patients was constituted by married women. This observation is in conformity to what is reported by most of the published studies from other developing countries.11-19,23,29-33,47-53

Marital conflict and failure in love affairs were the most frequently admitted underlying motives for self inflicted burns in our patients. This observation conforms to many reported studies from Iran, India, Afghanistan and Iraq. There exists a considerable body of published literature on self-inflicted burns from Iran wherein marital and interpersonal conflicts, and various forms of oppression and violence against women have been recognized as the triggering factors. Such domestic and spousal disharmony is further compounded by low family income, unemployment of the spouses, and low levels of literacy among women.11-13,16,29-31,40,47,53-55

As the victims are physically, emotionally, or mentally tortured by their husband, husband’s family, or even their own family members, the young women’ act has been referred to as a ‘‘cry for help’’ with the victims finding this self-humiliating act as a means of both escaping from intolerable conditions as well as speaking out against their abuse.11,16,29 Groohi et al.30 identified quarrel with a family member/relative and marital conflicts as the major factors precipitating suicidal burns.

Maghsoudi et al.39 reported domestic violence against women as one of the precipitating factors for suicidal burns. In contrast to the societal picture in Pakistan and Iran, the social dynamics in India are yet different and young wives commit burn suicides in response to the pressure of dowry disputes. Additionally, the young bride is typically living in a joint family where she is expected to perform majority of the household chores. She is not given say over choice of husbands. Historically in the past, the Indian widow women were forced to set themselves ablaze at the funeral of their husbands in the name of “sati”.17,56

In Afghanistan, the situation is even more sinister with majority of burn suicides occurring among women as a reaction to their gross social deprivation. For instance, women are strictly under the authority of the father or husband and cannot have the opportunity to assert economic and social independence. They are also faced with inhuman acts of Badal, wherein women are exchanged for material goods and money.20,57,58

Al-Zacko et al. in Iraq have related the burn suicides among women to the major changes happening at their age; the transition from youth to adulthood and adolescent marriages, with all the responsibilities coming particularly on young girls who are quite often ill-prepared to play the role of housewives.19

Contrary to all the aforementioned observations in studies from the developing economies, the situation in the developed and Western nations is different and burn suicides have been reported to be more common among men, slightly of higher age group, and among individuals with co-morbid substance abuse, and psychiatric and adjustment disorders.37,41,46,59-63

In our series, majority of the patients were illiterate. This observation conforms to the published literature from developing countries like Iran and India.11-17,29-32,39,46,53-58 One possible explanation for this is that education greatly improves the personality of the individual and enhances her understanding of daily life situations and family dynamics. Also education empowers women who can better voice their concerns about any injustices and get their rights more efficiently. This helps to avert the possibility of self-defeating behavior and indulgence in suicidal activities.46,53-58

In our series, majority of the patients were from rural areas. The published literature has also reported a higher rate of suicidal burns among the rural population than the urban population.11-16 In our series, the bulk of patients was constituted by those with over 50% TBSA burnt. Our observation conforms to most studies on self-immolation which have reported a greater total body surface area affected, with higher incidence of smoke inhalation injury, and with more difficult course of illness.17-19,64,65

The mortality rate in our series was 84.95%. Other published studies have also reported high mortality rates, ranging from 25 to 90%.17-19,64,65 In developing countries, the course and outcome is reported to be generally more severe with most women not reaching the hospital and most dying within the first 24 h.17,66 Two of our patients presented with self inflicted burns in the court premises as a symbolic measure of protest. Political protest is a relatively rare motivation for self-immolation. Published literature has similar examples of political protesting with self-immolation.34 Such protests often receive vast coverage by the mass media and trigger political and civil unrests.

Not surprising we faced great difficulty in extracting true story of the events underlying burn suicides among our patients. At the very outset, the patients as well as the attending family members denied the case as one of self-inflicted burns and insisted on its being an accidental event. They often narrated different false stories, which an experienced burn care provider would prudently tamper with clinical judgments of the circumstantial evidences surrounding the suicidal event plus the typical stereotyped distribution of the burn injuries. Several published studies have expressed similar observations of their patients’ behavior and related them to social and religious factors and the tendency to hide the precipitating social stressors.9,67

Our study has some strength as well as presents some limitations. It is the first local study which has tried to identify factors associated with self inflicted burn injuries among adults in Pakistan and hence established evidence base regarding this important health issue. As it was a hospital based study, we could not measure the exact incidence of burn suicides and attempted burn suicides at our typical population level. Although all the surviving individuals were routinely referred to psychiatrist, our study did not include their long term follow up to document the residual post-burn physical and psychiatric morbidity amongst them. We recommend the conduct of further local studies to improve upon these limitations.

The most common sufferers of self inflicted burn injuries were young, married, illiterate, housewives belonging to a rural background. Marital conflicts constituted the most common triggering cause for such injuries. These injuries carry considerable mortality and morbidity of prolonged hospitalization among otherwise fit young individuals. Our study highlights the gravity of this major but neglected catastrophe in our resource constrained economy. There is dire need to institute appropriate measures to address the issue in a national perspective.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footenote

Please cite this paper as:

Saaiq M, Ashraf B. Epidemiology and Outcome of Self-Inflicted Burns at Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences, Islamabad. World J Plast Surg 2014;3(2):107-114.

References

- 1.Mohammadi AA, Amini M, Mehrabani D, Kiani Z, Seddigh A. A survey on 30 months electrical burns in Shiraz University of Medical Sciences Burn Hospital. Burns. 2008;34:111–3. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pasalar M, Mohammadi AA, Rajaeefard AR, Neghab M, Tolidie HR, Mehrabani D. Epidemiology of burns during pregnancy in southern Iran: Effect on maternal and fetal outcomes. World Appl Sci J. 2013;28:153–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gore MA, Akolekar D. Evaluation of banana leaf dressing for partial thickness burn wounds. Burns. 2003;29:487–92. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(03)00050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manafi A, Kohanteb J, Mehrabani D, Japoni A, Amini M, Naghmachi M, Zaghi A, Khalili N. Active immunization using exotoxin A confers protection against Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in a mouse burn model. BMC J Microbiol. 2009;9:19–23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hosseini SV, Tanideh N, Kohanteb J, Ghodrati Z, Mehrabani D, Yarmohammadi H. Comparison between Alpha and silver sulfadiazine ointments in treatment of Pseudomonas infections in 3rd degree burns. Int J Surg. 2007;5:23–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hosseini SV, Niknahad H, Fakhar N, Rezaianzadeh A, Mehrabani D. The healing effect of honey, putty, vitriol and olive oil in Psudomonas areoginosa infected burns in experimental rat model. Asian J Anim Vet Adv. 2011;6:572–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hazrati M, Mehrabani D, Japoni A, Montasery H, Azarpira N, Hamidian-shirazi AR, Tanideh N. Effect of honey on healing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infected burn wounds in rat. J Appl Anim Res. 2010;37:161–5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amini M, Kherad M, Mehrabani D, Azarpira N, Panjehshahin Mr, Tanideh N. Effect of Plantago major on burn wound healing in rat. J Appl Anim Res. 2010;37:53–6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mabrouk AR, Mahmod Omar AN, Massoud K, Sherif MM, El Sayed N. Suicide by burns: a tragic end. Burns. 1999;25:337–9. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(98)00179-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Burn Association. National burn repository (R): report of data from 1999–2008; version 5. 0 [Internet] Chicago, IL: American Burn Association; 2009. Available from: http://www.ameriburn.org/2009NBRAnnualReport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmadi A. Suicide by self-immolation: comprehensive overview, experiences and suggestions. J Burn Care Res. 2007;28:30–41. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013E31802C8878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramim T, Mobayen M, Shoar N, Naderan M, Shoar S. Burnt wives in Tehran: a warm tragedy of self-injury. Int J Burn Trauma. 2013;3:66–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohammadi AA, Danesh N, Sabet B, Jalaeian H, Mohammadi MK. Self-burning: a common and tragic way of suicide in Fars province, Iran. Iran J Med Sci. 2008;33:110–3. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suhrabi Z, Delpisheh A, Taghinejad H. Tragedy of women’s self-immolation in Iran and developing communities: a review. Int J Burn Trauma. 2012;2:93–104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rezaeian M. Epidemiology of self-immolation. Burns. 2013;39:184–6. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lari AR, Joghataei MT, Adli YR, Zadeh YA, Alaghehbandan R. Epidemiology of suicide by burns in the province of Isfahan, Iran. J Burn Care Res. 2007;28:307–11. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0B013E318031A27F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar V. Burnt wives -- a study of suicides. Burns. 2003;29:31–5. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(02)00235-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laloe V, Ganesan M. Self-immolation a common suicidal behavior in eastern Sri Lanka. Burns. 2002;28:475–80. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(02)00047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Zacko SM. Self-inflicted burns in Mosul: a cross-sectional study. Ann Burns Fire Disaster. 2012;25:121–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Astill J. Desperate Afghan women seek escape in self-immolation: distributing rise in suicide despite the fall of the misogynist taliban. UK: 2004. avialble at: http://www.rense.com.general52/self.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. Health Statistics and Health Information Systems. Cause-specific mortality: World Bank income groups estimates for 2008. Geneva [CH]: World Health Organization; 2008. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates_regional/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saadat M. Epidemiology and mortality of hospitalized burn patients in Kohkiluye va Boyerahmad province (Iran):2002-2004. Burns. 2005;31:306–9. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsati E, Iconomou T, Tzivaridou D, Keramidas E, Papadopoulos S, Tsoutsos D. Self inflicted burns in Athens: a six year retrospective study. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2005;26:75–8. doi: 10.1097/01.bcr.0000150304.30777.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iqbal T, Saaiq M. Epidemiology and outcome of burns: Early experience at the country’s first national burns center. Burns. 2013;39:358–62. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmed I, Farooq U, Afzal W, Salman M. Medicolegal aspect of burn victims: A ten years study. Pak J Med Sci. 2009;25:797–800. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saaiq M, Zaib S, Ahmad Sh. Early excision and grafting versus delayed excision and grafting of deep thermal burns up to 40% total body surface area: A comparison of outcome. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2012;25:143–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tahir SM, Memon AR, Kumar M, Ali SA. Self inflicted burn; a high tide. J Pak Med Assoc. 2010;60:338–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saaiq M, Zaib S, Ahmad Sh. The menace of postburn contractures: A developing country’s perspective. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2012;25:152–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alaghehbandan R, Lari AR, Joghataei MT, Islami A Motavalian A. A prospective population-based study of suicidal behavior by burns in the province of Ilam, Iran. Burns. 2011;37:164–9. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Groohi B, Rossignol AM, Barrero SP, Alaghehbandan R. Suicidal behavior by burns among adolescents in Kurdistan, Iran: a social tragedy. Crisis. 2006;27:16–21. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.27.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmadi A, Mohammadi R, Stavrinos D, Almasi A, Schwebel DC. Self-immolation in Iran. J Burn Care Res. 2008;29:451–60. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31817112f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zarghami M, Khalilian A. Deliberate self-burning in Mazandaran, Iran. Burns. 2002;28:115–119. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(01)00092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campbell E. Perspectives on self-immolation experiences among Uzbek women. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peck MD. Epidemiology of burns throughout the World Part II: intentional burns in adults. Burns. 2012;38:630–7. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2011.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raj A, Gomez C, Silverman JG. Driven to a firy death- the tragedy of self-immolation in Afghanistan. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2201–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0801340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ben Meir P, Sagi A, Ben Yakar Y, Rosenberg L. Suicide attempts by self-immolation—our experience. Burns. 1990;16:257–8. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(90)90135-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cameron DR, Pegg SP, Muller M. Self-inflicted burns. Burns. 1997;23:519–21. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(97)00039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laloe V. Patterns of deliberate self-burning in various parts of the world A review. Burns. 2004;30:207–15. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2003.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maghsoudi H, Garadagi A, Jafary GA, Azarmir G, Aali N, Karimian B, Tabrizi M. Women victims of self-inflicted burns in Tabriz, Iran. Burns. 2004;30:217–20. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Forjuoh SN. Burns in low- and middle-income countries: A review of available literature on descriptive epidemiology, risk factors, treatment, and prevention. Burns. 2006;32:529–37. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chan RC, Burd A. Suicidal burn in Hong Kong. Burns. 2012;38:937–41. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seoighe DM, Conroy F, Hennessy G, Meagher P, Eadie P. Self-inflicted burns in the Irish national burns unit. Burns. 2011;37:1229–32. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Donoghue J, Panchal J, O’Sullivan S, O’Shaughnessy M, O’Connor TP, Keeley H, Kelleher MJ. A study of suicide and attempted suicide by self-immolation in an Irish psychiatric population: an increasing problem. Burns. 1998;24:144–6. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(97)00096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Henderson A, Wijewardena A, Streimer J, Vandervord J. Self-inflicted burns: A case series. Burns. 2013;39:335–40. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Poeschla B, Combs H, Livingstone S, Romma S, Klein MB. Self-immolation: Socioeconomic, cultural and psychiatric patterns. Burns. 2011;37:1049–57. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Malic CC, Karoo ROS, Austin O, Phipps A. Burns inflicted by self or by others—An 11 year snapshot. Burns. 2007;33:9 2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rezaie L, Khazaie H, Soleimani A, Schwebel DC. Is self-immolation a distinct method for suicide? A comparison of Iranian patients attempting suicide by self-immolation and by poisoning. Burns. 2011;37:159–63. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mohammadi AA, Danesh N, Sabet B, Amini M, Jalaeian H. Self inflicted burn injuries in southwest Iran. Burn Care Res. 2008;29:778–83. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31818481ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ansari-Lari M, Askarian M. Epidemiology of burns presenting to an emergency department in Shiraz, south Iran. Burns. 2003;29:579–81. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(03)00066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hosseini RS, Askarian M, Assadian O. Epidemiology of hospitalized female burns patients in a burn center in Shiraz. East Mediterr Health. 2007;13:113–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ytterstad B, Ahmadi A. Prevention of self-immolation by community-based intervention. Burns. 2007;33:1032–40. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2006.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ahmadi A, Mohammadi M, Schwebel DC, Hassanzadeh M, Yari M. Classic philosophy lessons and prevented self-inflicted burns: a call for action. Burns. 2009;35:154–5. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2008.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ahmadi A, Mohammadi R, Schwebel DC, Yeganeh N, Soroush A, Bazargan-Hejazi S. Familial risk factors for self-immolation: a case–control study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009;18:1025–31. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rastegar Lari A, Alaghehbandan R, Panjeshahin MR, Joghataei MT. Suicidal behavior by burns in the province of Fars, Iran: a socio-epidemiologic approach. Crisis. 2009;30:98–101. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.30.2.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Razaeian M. Suicide among young Middle Eastern Muslim females. Crisis. 2010;31:36–42. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bhugra D. Sati: a type of nonpsychiatric suicide. Crisis. 2005;26:73–7. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.26.2.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gall C. For more Afghan women, immolation is escape. The New York Times; [Google Scholar]

- 58.Padovese V, De Martino R, Eshan MA, Racalbuto V, Oryakhail MA. Epidemiology and outcome of burns in Esteqlal Hospital of Kabul, Afghanistan. Burns. 2010;36:1101–6. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thombs BD, Bresnick MG, Magyar-Russell G. Who attempts suicide by burning? An analysis of age patterns of mortality by self-inflicted burning in the United States. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:224–50. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rashid A, Gowar JP. A review of trends of self-inflicted burns. Burns. 2004;30:573–6. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Friedman T, Shalom A, Westreich M. Self-inflicted burns. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;58:622–4. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000250844.75189.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Palmu R, Isometsä E, Suominen K, Vuola J, Leppävuori A, Lönnqvist J. Self-inflicted burns: an eight year retrospective study in Finland. Burns. 2004;30:443–7. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2004.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Modjarrad K, McGwin Jr G, Cross JM, Rue 3rd LW. The descriptive epidemiology of intentional burns in the United States: an analysis of the National Burn Repository. Burns. 2007;3:828–32. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Horner BM, Ahmadi H, Mulholland R, Myers SR, Catalan J. Case-controlled study of patients with self-inflicted burns. Burns. 2005;31:471–5. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hadjiiski O, Todorov P. Suicide by self-inflicted burns. Burns. 1996;22:381–3. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(95)00172-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Campbell EA, Guiao IZ. Muslim culture and female selfimmolation: implications for global women’s health research and practice. Health Care Women Int. 2004;25:782–93. doi: 10.1080/07399330490503159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wallace KL, Pegg SP. Self-inflicted burn injuries: an 11-year retrospective study. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1999;20:191–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]