Abstract

Speckle-type POZ (pox virus and zinc finger protein) protein (SPOP) is an E3 ubiquitin ligase adaptor protein that is frequently mutated in prostate and endometrial cancers. All the cancer-associated SPOP mutations reported to date are clustered in the meprin and TRAF homology (MATH) domain, presumably affecting substrate binding. SPOP mutations in prostate cancer are mutually exclusive with the ETS family gene rearrangements and define a distinct molecular subclass of prostate cancer. SPOP mutations contribute to prostate cancer development by altering the steady-state levels of key components in the androgen-signaling pathway.

Introduction

Ubiquitination is a post-translational mechanism that regulates crucial cellular processes such as cell proliferation, differentiation, transcription, apoptosis, among others [1]. In an evolutionarily conserved, highly orchestrated process an enzymatic cascade catalyzes the covalent attachment of ubiquitin, a 76-amino-acid polypeptide, to a wide array of substrate proteins. Ubiquitination can dictate several distinct fates for the substrate proteins; for example, targeting them to the proteasome for degradation or altering their subcellular localization. Briefly, ubiquitin is activated in an ATP-dependent reaction catalyzed by the E1 activating enzyme. The activated ubiquitin is then transiently carried by the E2 conjugating enzyme, which, along with the E3 ubiquitin ligase, transfers the ubiquitin to its specific substrate. The E3 ubiquitin ligases confer substrate specificity for ubiquitin ligation. Mammalian cells typically contain a few E1, 30–40 E2 and several hundred different E3 ubiquitin ligases. The complex interplay between the E1, E2 and E3 ubiquitin ligases permits an enormous number of substrates to be modified and thereby contributes toward the specificity and diversity of the ubiquitination process. The most prominent E3 ligase family is the Cullin-RING E3 ubiquitin ligase that consists of a molecular scaffold (Cullin) connecting the substrate-specific adaptor protein to a catalytic component consisting of a RING finger domain and an E2 ubiquitin conjugating enzyme. Mammalian cells express a number of Cullin scaffold proteins, for example Cullin 1, Cullin 2, Cullin 3, Cullin 4A, Cullin 4B, Cullin 5, Cullin 7 and Cullin 9 [2,3]. The binding of the Cullins to their unique substrate-binding adaptor proteins provides specificity to the E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. One such substrate-binding adaptor protein that has gained increased attention owing to its far-reaching effects in cellular physiology and in pathological conditions like prostate cancer is the speckle-type POZ (pox virus and zinc finger protein) protein (SPOP).

Historically, antibodies from patients with autoimmune disorders have been crucial in the discovery of novel nuclear antigens [4,5]. For example, immunostaining of COS7 cells with the serum from a scleroderma patient revealed a unique speckled pattern in the nuclei that could not be attributed to known antigens. Further characterization revealed that the novel nuclear antigen was a part of a 374-amino-acid protein with a POZ domain [6] and a meprin and TRAF homology (MATH) domain [7]. The novel protein was named SPOP owing to its discrete speckled nuclear staining pattern and the presence of a POZ domain [6]. From an evolutionary standpoint, SPOP appears to be rather conserved; its orthologs, MEL-26 in Caenorhabditis elegans and HIB in Drosophila melanogaster exhibit sequence similarity and carry out functions analogous to their mammalian counterparts [7,8].

Structure of the SPOP protein

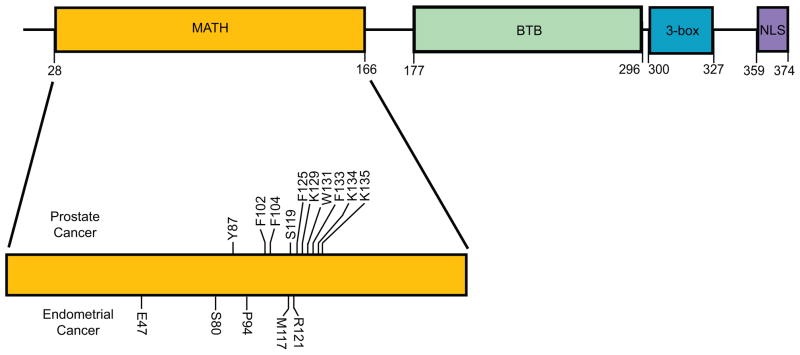

Structurally, the 42 kDa protein SPOP comprises an N-terminal MATH domain, a bric-a-brac, tramtrack and broad complex (BTB)/POZ domain, a 3-box domain and a C-terminal nuclear localization sequence (Figure 1). The MATH domain is primarily involved in substrate recognition and binding. Substrate binding is promoted by characteristic amino acid residues Y87, F102, Y123, W131 and F133 present in the MATH domain of SPOP. In turn, the substrate proteins require the presence of a characteristic SPOP-binding consensus (SBC) motif ϕ-π-S-S/T-S/T (ϕ = nonpolar, π = polar) as a prerequisite for binding to SPOP [9]. Such signature SBC motifs have been reported in SPOP substrates like Macro H2A, Puc, Daxx, Gli, among others. Phosphorylation of the SBC motif could block the binding of substrates to SPOP, although more studies are needed to clarify this point [9].

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the speckle-type POZ (pox virus and zinc finger protein) protein (SPOP) protein. The various domains are shown as boxes. The locations of amino acid residues mutated in prostate and endometrial cancers are shown.

As the MATH domain of SPOP binds to the substrate, the domain that connects it to the Cullin 3-RING box 1 scaffold protein is the conserved hydrophobic BTB domain [10–12]. A α3-β4 loop consisting of ten amino acid residues in the BTB domain is essential for the SPOP-Cullin 3 interaction. The presence of a motif ϕ-x-E (ϕ represents a hydrophobic residue, often Met or Leu, x represents any residue and E represents a glutamate residue) corresponding to residues M233, E234 and E235 in SPOP, in the α3-β4 loop common to many Cullin 3 adaptor proteins, appears to be important for binding to the scaffold. Recent research reveals that the binding of SPOP to Cullin 3 might not be entirely restricted to its BTB domain. A pair of α-helices stretching beyond the BTB domain, called 3-box, has been suggested to enhance the binding with Cullin 3 [9,13]. In addition to binding to the scaffold protein, the BTB domain is involved in dimerization of SPOP. Four key residues, L186, L190, L193 and I217, are involved in creating a hydrophobic interface that allows the residues 177–297 to form SPOP dimers. Dimerization-defective SPOP mutants continue to bind to Cullin 3 without a significant decrease in affinity, but exhibit impaired ubiquitination. The functional SPOP-Cullin 3-RING box 1 ubiquitin ligase complex contains two substrate-binding sites from SPOP and two catalytic cores from Cullin 3-RING box 1 [9]. The E3 ligase activity is further enhanced when the BTB domain and the C-terminal domain of SPOP function together to form higher-order SPOP-Cullin 3-RING box 1 ubiquitin ligase complex oligomers. Such oligomers augment the E3 activity by enhancing the substrate avidity and by increasing the effective concentration of the E2 ubiquitin conjugating enzyme [13,14]. Interestingly, the Cullin 3-RING box 1 ubiquitin ligase complex requires a neddylation post-translational modification for its function. There is evidence suggesting SPOP as a promoter of the NEDD8 modification of Cullin 3 [15], although the exact mechanisms are unclear.

SPOP as a regulator of cellular function

SPOP substrates are implicated in several essential cellular functions (Table 1) [16–25]. For example, death-associated protein 6 (DAXX), a protein involved in transcription, cell-cycle regulation and apoptosis, is a substrate of SPOP. DAXX binds to the MATH domain of SPOP and is subsequently ubiquitinated and targeted for degradation in the proteasome [15,19]. When DAXX interacts with ETS-1, it represses the transcriptional activation of ETS-1 target genes [26]. Degradation of DAXX by the SPOP-Cullin 3-RING box 1 ubiquitin ligase results in the reversal of transcription repression of ETS-1 target genes and represents one of the mechanisms by which SPOP regulates gene expression. The primary function of SPOP-Cullin 3-RING box 1 ubiquitin ligase is to target various substrates to the proteasome for degradation. However, specialized functions involving subcellular localization of proteins involved in X-inactivation have been attributed to SPOP. The process by which one of the two X chromosomes in XX females is stably silenced, referred to as X-inactivation, is essential for normal physiological functioning. One of the steps involved is the concentration of a histone variant Macro H2A on the X chromosome marked for inactivation. The MATH domain of SPOP binds to the leucine zipper region of Macro H2A and subsequently localizes it to the inactivated X chromosome [16,18]. Other examples of substrates that might not undergo proteolysis upon binding to SPOP are phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and the polycomb group protein Bmi1 [18,20].

Table 1.

The mammalian substrates of SPOP that bind to its MATH domain and the diverse effects they exert on the cells

| Mammalian SPOP-binding substrate | Pathway or process involved | Refs |

|---|---|---|

| Macro H2A | X-inactivation | [16] |

| Pancreatic–duodenal homeobox 1 | Development and differentiation in pancreas, transcription regulation | [17] |

| Death-domain-associated protein | Apoptosis | [19] |

| Polycomb group protein Bmi1 | Transcriptional repressor | [18] |

| Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase | Secondary messenger formation | [20] |

| Gli2 | Transcription regulation in the Hedgehog pathway | [25] |

| Gli3 | Transcription regulation in the Hedgehog pathway | [25] |

| Breast cancer metastasis suppressor 1 | Transcriptional repressor | [21] |

| Steroid receptor co-activator-3 | Co-activator in estrogen and androgen receptor signaling | [22] |

| Androgen receptor | Ligand-activated transcription factors in hormone-dependent signaling | [23] |

| Phosphatase and tensin homolog | Phosphatase in PI3K signaling pathway | [24] |

| Dual specificity phosphatase 7 | Phosphatase in MAP kinase pathway | [24] |

Abbreviations: MAP, mitogen-activated protein; MATH, meprin and TRAF homology; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase; SPOP, speckle-type POZ protein.

SPOP in human cancers

SPOP was first reported as a significantly mutated gene in human prostate cancers in a study that analyzed somatic mutations in 58 tumors [27]. Next, whole-genome sequencing of seven primary prostate tumors and matched normal tissue biopsies revealed SPOP mutations in two of the tumor samples, but none in the matched normal samples [28]. In subsequent studies, SPOP mutations were identified in 6–13% of primary prostate adenocarcinomas and 14.5% of metastatic prostate cancers [29–31]. The observation of SPOP mutations in high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HG-PIN) adjacent to invasive adenocarcinoma suggests that SPOP mutations are early events in prostate tumorigenesis. Comprehensive analysis of SPOP in 720 prostate cancer samples from six international cohorts spanning Caucasian, African American and Asian patients resulted in the identification of SPOP mutations in 4.6–14.4% of patients with prostate cancer across different ethnic and demographic backgrounds [32]. From these results, it appears that SPOP mutations are not associated with ethnicity, biochemical recurrence, clinical or pathologic parameters. A recent study conducted on a single patient described the evolution of prostate cancer from the primary cancer to metastasis by longitudinal sampling during disease progression and at the time of death. Interestingly, SPOP was mutated in the lethal metastatic cell clone and the primary cancer lesion sharing characteristics of the lethal clone [33]. Taken together, these studies suggest that SPOP mutations are early and recurrent events in prostate cancer.

The TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusions are observed in >50% of human prostate cancers [34]. Prostate cancers with SPOP mutations are inversely associated with ERG rearrangements, but are highly enriched for chromodomain-helicase-DNA-binding protein (CHD)1 deletions across multiple cohorts [29,32]. A recent exome-sequencing study revealed that 8% of serous endometrial cancers and 9% of clear cell endometrial cancers have SPOP mutations [35]. All the SPOP mutations identified to date in prostate and endometrial cancers cluster in the MATH domain, presumably affecting substrate binding (Figure 1). Phenylalanine 133 in the MATH domain is the most frequently mutated residue in prostate cancers. Although SPOP has a definitive tumor suppressor role in prostate and endometrial cancers, it has a tumor promoting role in kidney cancer [24]. SPOP protein is highly expressed in 99% of clear cell renal cell carcinomas (RCCs), the most prevalent form of kidney cancer [36]. However, there are no reports of SPOP mutations in kidney cancers. The paradoxical observation of tumor-promoting and tumor-suppressing activities of SPOP can be partially explained by (i) altered substrate availability owing to differential subcellular localization of SPOP or (ii) differential expression of SPOP substrates in various cell and cancer types. If the majority of substrates that bind to SPOP in a cell type have tumor-suppressor roles, SPOP overexpression can have a tumor promoting role. Similarly, SPOP mutations that abrogate substrate binding can have a tumor promoting role if a majority of the substrates also have a tumor promoting role. Hence, the role of SPOP expression levels and mutation status in cancer development is context dependent.

Functional consequences of SPOP mutations in prostate cancer

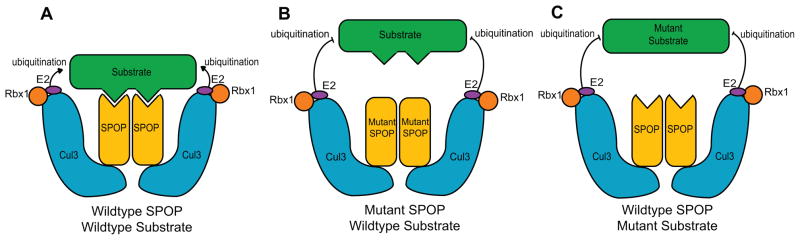

SPOP has recently been shown to be a component of the DNA damage response (DDR) machinery. SPOP depletion results in an impaired DDR and hypersensitivity to ionizing radiation [37]. The tumor suppressor role of SPOP in prostate and endometrial cancers is supported by the clustering of mutations in the MATH domain. Knockdown of SPOP using siRNA or overexpression of the F133V MATH domain variant enhanced the invasive properties of prostate cancer cells [29]. The MATH domain mutations are predicted to result in loss of SPOP function, thereby impairing substrate binding and targeting for ubiquitin-mediated degradation (Figure 2). Two classic examples for SPOP substrates in the context of prostate cancer are androgen receptor (AR) and steroid receptor coactivator (SRC)-3.

Figure 2.

Proposed mechanism for the role of speckle-type POZ (pox virus and zinc finger protein) protein (SPOP) mutations in prostate cancer. Wild-type SPOP binds to its substrates, which are then targeted for ubiquitin-mediated degradation by the SPOP-Cullin 3-RING box 1 ubiquitin ligase and E2 conjugating enzyme (a). Mutations in SPOP, which block its interaction with the substrate (b), or substrate mutations that block the interaction with SPOP (c), help the substrate to escape from ubiquitin-mediated degradation.

A recent study has implicated AR as a direct target of SPOP [23]. AR, a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily, is essential for normal prostate cell growth and survival, and is also important for initiation and progression of prostate cancer. AR harbors a SPOP-binding consensus motif, and binds to SPOP in vitro and in vivo. Upon binding to SPOP, AR undergoes ubiquitin-mediated degradation. AR splice variants that lack the SPOP-binding consensus motif escape this degradation. Interestingly, prostate-cancer-associated SPOP mutants do not bind to AR or promote its degradation. SPOP-mediated degradation of AR is promoted by antiandrogens and blocked by androgens. Because glucocorticoid receptor (GR), another member of the nuclear receptor superfamily, has been recently implicated in acquired resistance to antiandrogens [38], future studies should address whether SPOP can interact with other nuclear receptors.

SRC-3, a preferred co-activator for hormone-activated AR, is a member of the p160 SRC family that also includes SRC-1 and SRC-2 [39,40]. Genetic ablation of SRC-3 inhibits spontaneous prostate cancer progression in the transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate (TRAMP) model [41]. SRC-3 directly interacts with SPOP, which promotes its Cullin-3-dependent ubiquitination and degradation [22]. Similar to AR, prostate-cancer-associated mutants of SPOP do not interact with SRC-3 protein, and thereby fail to promote its ubiquitination and degradation, indicative of a common theme [42]. Because SRC-3 is overexpressed in endometrial carcinomas [43], it will be interesting to determine whether endometrial-cancer-associated SPOP mutants also interact with SRC-3 protein and alter its steady-state levels. In summary, SPOP mutations promote prostate cancer development by altering the steady-state levels of the key components of the androgen signaling pathway.

Concluding remarks

SPOP is an adaptor protein that aids in the degradation of several substrates that have important roles in cellular development and physiology. SPOP mutations define a distinct molecular subclass of prostate cancer, and are also observed in endometrial cancers. Future studies should address whether SPOP mutations in prostate cancer have any association with clinical outcome and risk stratification. Further insights into the mechanistic basis of SPOP-mediated cancer development can be obtained by the development of suitable animal models. Systematic identification and characterization of SPOP substrates can potentially help in the development of novel cancer therapeutics.

Highlights.

This article was commissioned for Drug Discovery Today: Therapeutic Strategies

It is now being published as a themed section in Drug Discovery Today

It forms part of a section on cancer and leukemia

Acknowledgments

I apologize to those whose relevant research was not cited owing to space limitations. I thank Susmita Ramanand and Maxwell Tran for insightful comments, and Aparna Ghosh for help with figure preparation. This work was supported in part by a Young Investigator Award from the Prostate Cancer Foundation and the NIH Pathway to Independence (PI) Award (K99/R00) K99CA160640.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hershko A, et al. Basic Medical Research Award. The ubiquitin system. Nat Med. 2000;6:1073–1081. doi: 10.1038/80384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pei XH, et al. Cytoplasmic CUL9/PARC ubiquitin ligase is a tumor suppressor and promotes p53-dependent apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2969–2977. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petroski MD, Deshaies RJ. Function and regulation of cullin-RING ubiquitin ligases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:9–20. doi: 10.1038/nrm1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ascoli CA, Maul GG. Identification of a novel nuclear domain. J Cell Biol. 1991;112:785–795. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.5.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrade LE, et al. Human autoantibody to a novel protein of the nuclear coiled body: immunological characterization and cDNA cloning of p80-coilin. J Exp Med. 1991;173:1407–1419. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.6.1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagai Y, et al. Identification of a novel nuclear speckle-type protein, SPOP. FEBS Lett. 1997;418:23–26. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01340-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zapata JM, et al. A diverse family of proteins containing tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor domains. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:24242–24252. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100354200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Q, et al. A hedgehog-induced BTB protein modulates hedgehog signaling by degrading Ci/Gli transcription factor. Dev Cell. 2006;10:719–729. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhuang M, et al. Structures of SPOP-substrate complexes: insights into molecular architectures of BTB-Cul3 ubiquitin ligases. Mol Cell. 2009;36:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu L, et al. BTB proteins are substrate-specific adaptors in an SCF-like modular ubiquitin ligase containing CUL-3. Nature. 2003;425:316–321. doi: 10.1038/nature01985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furukawa M, et al. Targeting of protein ubiquitination by BTB-Cullin 3-Roc1 ubiquitin ligases. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:1001–1007. doi: 10.1038/ncb1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pintard L, et al. The BTB protein MEL-26 is a substrate-specific adaptor of the CUL-3 ubiquitin-ligase. Nature. 2003;425:311–316. doi: 10.1038/nature01959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Errington WJ, et al. Adaptor protein self-assembly drives the control of a cullin-RING ubiquitin ligase. Structure. 2012;20:1141–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Geersdaele LK, et al. Structural basis of high-order oligomerization of the cullin-3 adaptor SPOP. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2013;69:1677–1684. doi: 10.1107/S0907444913012687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwon JE, et al. BTB domain-containing speckle-type POZ protein (SPOP) serves as an adaptor of Daxx for ubiquitination by Cul3-based ubiquitin ligase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:12664–12672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600204200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takahashi I, et al. MacroH2A1.2 binds the nuclear protein Spop. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1591:63–68. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(02)00249-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu A, et al. Identification of PCIF1, a POZ domain protein that inhibits PDX-1 (MODY4) transcriptional activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4372–4383. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4372-4383.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hernandez-Munoz I, et al. Stable X chromosome inactivation involves the PRC1 Polycomb complex and requires histone MACROH2A1 and the CULLIN3/SPOP ubiquitin E3 ligase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:7635–7640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408918102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.La M, et al. Daxx-mediated transcriptional repression of MMP1 gene is reversed by SPOP. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;320:760–765. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bunce MW, et al. Coordinated activation of the nuclear ubiquitin ligase Cul3-SPOP by the generation of phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:8678–8686. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710222200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim B, et al. Breast cancer metastasis suppressor 1 (BRMS1) is destabilized by the Cul3-SPOP E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;415:720–726. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.10.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li C, et al. Tumor-suppressor role for the SPOP ubiquitin ligase in signal-dependent proteolysis of the oncogenic co-activator SRC-3/AIB1. Oncogene. 2011;30:4350–4364. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.An J, et al. Destruction of full-length androgen receptor by wild-type SPOP, but not prostate-cancer-associated mutants. Cell Rep. 2014;6:657–669. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li G, et al. SPOP promotes tumorigenesis by acting as a key regulatory hub in kidney cancer. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:455–468. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang C, et al. Suppressor of fused and SPOP regulate the stability, processing and function of Gli2 and Gli3 full-length activators but not their repressors. Development. 2010;137:2001–2009. doi: 10.1242/dev.052126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li R, et al. EAP1/Daxx interacts with ETS1 and represses transcriptional activation of ETS1 target genes. Oncogene. 2000;19:745–753. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kan Z, et al. Diverse somatic mutation patterns and pathway alterations in human cancers. Nature. 2010;466:869–873. doi: 10.1038/nature09208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berger MF, et al. The genomic complexity of primary human prostate cancer. Nature. 2011;470:214–220. doi: 10.1038/nature09744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barbieri CE, et al. Exome sequencing identifies recurrent SPOP, FOXA1 and MED12 mutations in prostate cancer. Nat Genet. 2012;44:685–689. doi: 10.1038/ng.2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grasso CS, et al. The mutational landscape of lethal castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nature. 2012;487:239–243. doi: 10.1038/nature11125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baca SC, et al. Punctuated evolution of prostate cancer genomes. Cell. 2013;153:666–677. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blattner M, et al. SPOP mutations in prostate cancer across demographically diverse patient cohorts. Neoplasia. 2014;16:14–20. doi: 10.1593/neo.131704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haffner MC, et al. Tracking the clonal origin of lethal prostate cancer. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:4918–4922. doi: 10.1172/JCI70354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tomlins SA, et al. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science. 2005;310:644–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1117679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Gallo M, et al. Exome sequencing of serous endometrial tumors identifies recurrent somatic mutations in chromatin-remodeling and ubiquitin ligase complex genes. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1310–1315. doi: 10.1038/ng.2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu J, et al. Analysis of Drosophila segmentation network identifies a JNK pathway factor overexpressed in kidney cancer. Science. 2009;323:1218–1222. doi: 10.1126/science.1157669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang D, et al. Speckle-type POZ protein, SPOP, is involved in the DNA damage response. Carcinogenesis. 2014 doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arora VK, et al. Glucocorticoid receptor confers resistance to antiandrogens by bypassing androgen receptor blockade. Cell. 2013;155:1309–1322. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou XE, et al. Identification of SRC3/AIB1 as a preferred coactivator for hormone-activated androgen receptor. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:9161–9171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.085779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu J, et al. Normal and cancer-related functions of the p160 steroid receptor co-activator (SRC) family. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:615–630. doi: 10.1038/nrc2695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chung AC, et al. Genetic ablation of the amplified-in-breast cancer 1 inhibits spontaneous prostate cancer progression in mice. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5965–5975. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Geng C, et al. Prostate cancer-associated mutations in speckle-type POZ protein (SPOP) regulate steroid receptor coactivator 3 protein turnover. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:6997–7002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304502110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glaeser M, et al. Gene amplification and expression of the steroid receptor coactivator SRC3 (AIB1) in sporadic breast and endometrial carcinomas. Horm Metab Res. 2001;33:121–126. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-14938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]