Abstract

Chemokines are a large group of low molecular weight cytokines that are known to selectively attract and activate different cell types. Although the primary function of chemokines is well recognized as leukocyte attractants, recent evidences indicate that they also play a role in number of tumor-related processes, such as growth, angiogenesis and metastasis. Chemokines activate cells through cell surface seven trans-membranes, G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCR). The role played by chemokines and their receptors in tumor pathophysiology is complex as some chemokines favor tumor growth and metastasis, while others may enhance anti-tumor immunity. These diverse functions of chemokines establish them as key mediators between the tumor cells and their microenvironment and play critical role in tumor progression and metastasis. In this review, we present some of the recent advances in chemokine research with special emphasis on its role in tumor angiogenesis and metastasis.

Keywords: Chemokines, Tumor growth, Angiogenesis, Metastasis, Tumor microenvironment

1 Introduction

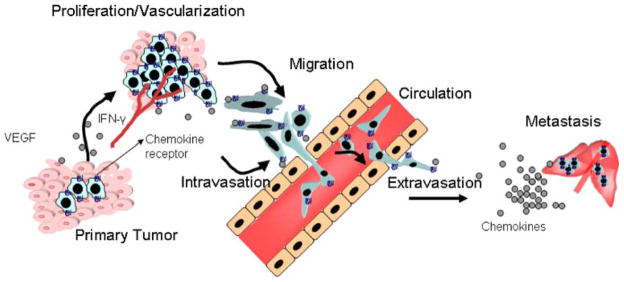

The process of cancer metastasis consists of a series of sequential interrelated steps, each of which can be rate-limiting [1]. The major steps in the formation of a metastasis are as follows: (1) following initial transforming event, growth of neoplastic cells must be progressive, which requires extensive vascularization if a tumor mass is to exceed 2-mm in diameter; (2) local invasion of the host stroma by some tumor cells occurs as thin-walled venules, like lymphatic channels, offer very little resistance to penetration by tumor cells and provide the most common pathway for tumor cell entry into the circulation; (3) detachment and embolization of tumor cell aggregates occurs with subsequent arrest in the capillary beds of organs; (4) extravasation to secondary organ; and (5) proliferation and neovascularization within the distant organ parenchyma to produce detectable metastatic lesions. Intrinsic properties of the tumor cells, as well as their surrounding microenvironment, are crucial in defining the progression of cancer and the fate of metastases. Several factors have been identified that facilitate the interplay between tumor cells and their microenvironment. Proliferation, neovascularization, invasion and migration of malignant cells to distinct organs are crucial steps for tumor progression and metastasis that can be regulated by chemokines (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The multifaceted role of chemokines in tumor growth, invasion and metastasis: Chemokines produced by tumor cells attract infiltrating leukocyte and/or promote proliferation and can also affect the microenvironment by promoting vascularization. Chemokines can stimulate their specific receptors that alter the adhesive capacity of tumor cells and their migration/invasion into circulation, and extravasation towards distant organs

Over the last 20 years, it has been increasingly recognized that chemokines play an important part in regulation of the metastatic cascade, as they are known to be expressed by tumor cells, as well as by host cells in their proximity and at metastatic sites. A clear understanding of emerging roles of chemokines and the mechanisms of their actions in the processes of malignant progression and metastasis will open new doors for therapeutic interventions. In this review, we will highlight functional roles of the chemokines and their receptors, with a focus on angiogenesis and distant metastasis.

2 Chemokines and their receptors

The chemokine superfamily includes a large number of low molecular weight chemotactic proteins that regulate the trafficking of leukocytes to inflammatory sites [2–4]. Chemokines are generally 8–11 kDa in size and contain four conserved cysteine amino acid residues linked by disulfide bonds. Structurally, chemokines are classified into four (CXC, CC, C and CX3C) subfamilies [3, 4]. There are more than 50 chemokines, the majority of which belong to the major CC and CXC chemokine subfamilies (Tables 1 and 2). According to a new classification, chemokine ligands/receptors are named ‘L’ or ‘R’, respectively [4]. Receptors are further grouped into four subfamilies, as each receptor binds to one of the four chemokine subfamilies (Tables 1 and 2). To avoid confusion, we have used the new designations and have listed their old and new names along with their respective receptors in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Human CXC, C and CX3C chemokines

| Chemokines | Alternate name (mouse protein) | Known receptor(s) |

|---|---|---|

| CXC (alpha chemokines) | ||

| CXCL1 | GRO-α/SCYB-1/MGSA/GRO-1/NAP-3 (MIP-2α/KC) | CXCR1, CXCR2 |

| CXCL2 | GRO-β/SCYB-2/GRO-2/MIp-2 α (MIP-2 β/KC) | CXCR2 |

| CXCL3 | GRO-γ/SCYB-3/GRO-3/MIp-2 β (KC) | CXCR2 |

| CXCL4 | PF-4/SCYB-4 | Unknown |

| CXCL5 | ENA-78/SCYB-5 (LIX) | CXCR2 |

| CXCL6 | GCP-2/SCYB-6 | CXCR1, CXCR2 |

| CXCL7 | NAP-2/(SCYB-7/PBP/CTAP-III/β-TG | CXCR1, CXCR2 |

| CXCL8 | SCYB-8/GCP-1/NAP-1/MDNCF | CXCR1, CXCR2 |

| CXCL9 | MIG/SCYB-9 | CXCR3 |

| CXCL10 | IP-10/SCYB-10 | CXCR3, KSHV-GPCR |

| CXCL11 | I-TAC/SCYB-11/β-R1/H174/IP-9 | CXCR3 |

| CXCL12 | SDF-1/SCYB-12/PBSF | CXCR4 |

| CXCL13 | BCA-1/SCYB-13 | CXCR5 |

| CXCL14 | BRAK/SCYB-14/Bolekine | unknown |

| CXCL16 | Small inducible cytokine B6 | CXCR6 |

| C (gamma chemokines) | ||

| XCL1 | Lymphotactin/SCYC1/SCM-1α/Lymphotactin α | XCR1 |

| XCL2 | SCM-1b/SCYC2/ymphotactin β | XCR1 |

| CX3C (delta chemokines) | ||

| CX3CL1 | Fractalkine/SCYD1 | CX3CR1 |

Table 2.

Human CC chemokines

| Chemokines (beta chemokines) | Alternate name (mouse protein) | Known receptor(s) |

|---|---|---|

| CCL1 | I-309/SCYA1 (TCA-3) | CCR8 |

| CCL2 | MCP-1/SCYA2/MCAF/HC11 (JE) | CCR2, CCR5, CCR10 |

| CCL3 | MIP-1α/SCYA 3/LD78α/SIS-α | CCR1, CCR5 |

| CCL4 | MIP-1β/SCYA4/ACT-2/G-26/HC21/LAG-1/SIS-γ | CCR5, CCR10 |

| CCL5 | RANTES/SCYA5/SIS-δ | CCR1, CCR3, CCR5, CCR10 |

| CCL7 | MCP-3/SCYA7 | CCR1, CCR2, CCR3 CCR5, |

| CCL8 | MCP-2/SCYA8/HC14 (MARC) | CCR2, CCR3, CCR5 CCR1, |

| CCL11 | Eotaxin/SCYA11 | CCR3 |

| CCL13 | MCP-4/SCYA13/Ck β10/NCC-1 | CCR1, CCR2, CCR3, CCR5 |

| CCL14 | HCC-1/SCYA14/Ck β1/MCIF/NCC-2/CC-1 | CCR1 |

| CCL15 | MIP-1 δ/SCYA15/Lkn-1/HCC-2/MIP-5/NCC-3/CC-2 | CCR1, CCR3 |

| CCL16 | HCC-4/SCYA16/Ck β12/LEC/LCC-1/NCC-4/ILINCK/LMC/Mtn-1 | CCR1 |

| CCL17 | TARC/SCYA17 (ABCD-2) | CCR4 |

| CCL18 | PARC/SCYA18/Ckβ7/DC-CK1/AMAC-1/MIP-4/DCtactin | unknown |

| CCL19 | MIP-3β/SCYA19/Ckβ11/ELC/Exodus-3 | CCR7 |

| CCL20 | MIP-3α/SCYA20/LARC/Exodus-1 | CCR6 |

| CCL21 | 6Ckine/SCYA21/Ckβ9/SLC/Exodus-2 | CCR7 |

| CCL22 | MDC/SCYA22 (ABCD-1) | CCR4 |

| CCL23 | MPIF/SCYA23/Ckβ8/Ckβ8–1/MIP-3/MPIP-1 | CCR1 |

| CCL24 | Eotaxin-2/SCYA24/Ckβ6/MPIF-2 | CCR3 |

| CCL25 | TECK/SCYA25/Ckβ15 | CCR9 |

| CCL26 | Eotaxin-3/SCYA26/MIP-4α/TSC-1/IMA | CCR3 |

| CCL27 | CTACK/SCYA27/ESkine/Skinkine | CCR3, CCR2, CCR10 |

| CCL28 | CCL28/SCYA28/MEC | CCR10, CCR3 |

2.1 CXC chemokines

Members of the CXC (or α-chemokine) subfamily contain one non-conserved amino acid (X) between the first and second cysteine residues. Based on the presence or absence of a Glu-Leu-Arg (ELR) motif, the CXC chemokines can be further subdivided into two groups (ELR+ and ELR−) [3–5]. The ELR motif is located at the N-terminus immediately before the first cysteine amino acid residue [6]. Extensive investigations regarding the functions of the CXC subfamily have revealed that the presence/absence of the ELR motif determines the chemokine is angiogenic or angiostatic [7, 8]. The ELR+ chemokines are primarily chemotactic for neutrophils, and hence, are potent promoters of angiogenesis [7–10]. On the other hand, the main target(s) for ELR− members are T cells and B cells and they are potent inhibitors of angiogenesis [11]. The angiogenic CXC chemokine family members include CXCL1–3 and CXCL5–8 [7] whereas, angiostatic CXC chemokine members include CXCL4 (12) and CXCL9–11 [8, 11–13]. Although CXCL12, an ELR− chemokine, was originally described as a pre B-cell growth stimulating factor [14], it has also been shown to exhibit angiogenic activity [15–18]. Furthermore, ELR− CXC chemokines have been shown to inhibit neovascularization induced by classical angiogenic factors, such as basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2) and vascular endothelial cell growth factor (VEGF) [11].

2.2 CC chemokines

The CC chemokines (or β-chemokines) represent the largest family of chemokines and have adjacent cysteine residues. The known members of this family are CCL1–5, CCL7–8, CCL11 and CCL13–28, which are listed in Table 2. Members of this family exhibit the most diverse range of target cell specificities. They generally attract leukocytes, including monocytes, macrophages, T cells, B cells, basophils, eosinophils, dendritic cells, mast cells and natural killer cells [19–27]. So far, neutrophils have not been shown to respond to chemotactic stimuli from any of the CC chemokines.

2.3 C chemokines

Chemokines of the C subfamily (γ-chemokines) have only one of the cysteine residues and XCL1 (lymphotactin) [28] is the only member of this subfamily, with a molecular size of 16 kDa. This chemokine seems to be lymphocyte specific [28].

2.4 CX3C chemokines

The CX3C chemokine (δ-chemokines) have three non-conserved amino acids between the first two cysteines [29]. This family also has only one known member CX3CL1 (Fractalkine), which has been shown to induce both the migration and the adhesion of leukocytes [30, 31]. In general, chemokines are secretory proteins, and CX3CL1 is the only exception being a membrane-bound chemokine [32].

2.5 Chemokine receptors

All chemokines exert their biological function by binding to G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR) [3, 5, 33]. Chemokine receptors have an N-terminus outside the cell, three extracellular and three intracellular loops, and a C-terminus containing serine and threonine phosphorylation sites in the cytoplasm. In addition, they also possess seven hydrophobic trans-membrane domains, three extracellular and three intracellular loops. Currently, six CXC receptors, ten CC receptors, and one receptor each for C and CX3C have been identified (Tables 1 and 2). Of the six CXC receptors, CXCR1 binds both CXCL8 and CXCL6 with high affinity [34, 35]. CXCR2, another receptor for CXCL8 has 78% identity with CXCR1 at the amino acid level. It has also been reported that CXCR2 can bind to all of the ELR+ CXC chemokines with high affinity [35–37]. The third receptor, CXCR3, has been shown to bind the ELR− CXC chemokines (CXCL9–11) [38–40]. CXCR4 has been shown to be a cofactor for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection of T lymphocytes [41]. For CXCR4, the only known ligand is CXCL12, and this ELR− CXC chemokine can inhibit HIV infection by competing with lymphotropic HIV virus for binding of CXCR4 [42]. CXCR5, identified as a receptor on B lymphocytes, is responsible for B cell chemotaxis mediated by CXCL13 [43]. CXCR6 is a receptor for CXCL16, and was described previously as a fusion cofactor for HIV-1 and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) [44, 45].

Among the CC chemokine receptors, CCR1 is a receptor for CCL3, CCL5, CCL7–8, CCL13–16 and CCL23 [46–50]. CCR2 exists as two splice variants, CCR2a and CCR2b, among them CCR2b is the most studied and appears to bind at least CCL2, CCL7–8, CCL13, and CCL27 [51–53]. CCR3 binds to CCL5, along with CCL7–8, CCL11, CCL13, NNY-CCL14 (CCL14 analogue), CCL15, CCL24 and CCL26–28 [26, 54–57]. CCR4 is a receptor for CCL17 and CCL22 [58, 59], whereas CCR5 is a major co-receptor for macrophage (M)-tropic HIV-1, HIV-2 and SIV strains [60]. CCR5 can bind to other CC chemokines (CCL2, CCL7–8 and CCL13) with decreased affinity [61]. CCR6 has been shown to be a receptor for CCL20 [62]. CCL19 and CCL21 bind to CCR7 [63] while CCR8 appears to bind CCL1 specifically [64]. CCR9 is a receptor for CCL25 [65]. Functional studies conducted on CCR10 indicate that it has high binding affinity for CCL2, CCL4, CCL27 and CCL28 [66, 67]. So far, one receptor each for C (XCR1) and CX3C (CX3CR1) chemokines have been identified (Table 1).

One of the remarkable features of the chemokine receptor superfamily is their promiscuity in ligand binding [68]. This suggests that the regulation of chemokine activities and the response in target cells are complex events. The intricate functional and regulatory nature of chemokine activities gives rise to diverse responses in normal homeostasis and pathological conditions, including angiogenesis and tumor metastasis.

3 Chemokines in angiogenesis

Angiogenesis is a biological process of new blood vessel formation from preexisting blood vessels and hence is also referred to as neovascularization. It is fundamental to many physiological as well as pathological processes in living organisms [69–72]. The process of angiogenesis is regulated by many angiogenic growth factors, enzymes, lipids and carbohydrates, including the members of the chemokine superfamily [8, 73]. Specific members of the chemokine superfamily can act as pro-angiogenic molecules and support the formation of new blood vessels, while others can antagonize these activities and therefore are angiostatic [9, 73].

Among all the chemokines, CXCL8 is extensively studied as a potent mediator of angiogenesis. The pro-angiogenic activity of CXCL8 in vivo was confirmed through the use of the rat mesenteric window assay, the rat and rabbit corneal assay, and a subcutaneous sponge model [74–77]. Human recombinant CXCL8 was shown to be angiogenic when implanted in the rat cornea and induced proliferation and chemotaxis of human umbilical vein endothelial cells [75]. In addition, the angiogenic properties of conditioned media from activated monocytes and macrophages were attenuated by CXCL8 anti-sense oligonucleotides [75]. Furthermore, it was shown that CXCL8 can act directly on vascular endothelial cells by promoting their survival [78]. Studies from our lab and other groups suggest that CXCL8 stimulates both endothelial proliferation and capillary tube formation in vitro in a dose dependent manner, and both of these effects can be blocked by monoclonal antibodies to CXCL8 [79, 80]. In addition, CXCL8 was shown to inhibit apoptosis of endothelial cells [81]. CXCL8 exerts its angiogenic activity by up-regulating MMP-2 and MMP-9 in tumor and endothelial cells [81–83]. Degradation of the extracellular matrix by MMPs is required for endothelial cell migration, organization, and, hence, angiogenesis [84]. It has been demonstrated by our group that CXCL8 directly enhances endothelial cell proliferation, survival, and MMP expression in CXCR1- and CXCR2-expressing endothelial cells, thus may be an important player in the process of angiogenesis [79].

Several investigators have suggested the angiogenic effect of CXCL8 is independent of its chemotactic and pro-inflammatory effects, since CXCL8 promotes angiogenesis in the absence of inflammatory cells [74, 77]. In addition, it has been reported that there is a direct correlation between high levels of CXCL8 and tumor angiogenesis, progression and metastasis in nude xenograft models of human cancer cells [83, 85]. In an experimental model of ovarian cancer, the expression of CXCL8 was directly correlated with neovascularization and poor survival [86]. CXCL8 may also play an important role in angiogenesis in prostate and breast cancer as serum levels of CXCL8 are elevated in patients with prostate and breast cancer, and correlate with disease stage [87–91]. The ability of CXCL8 to elicit angiogenic activity depends on the expression of its receptor by endothelial cells.

CXCL8 and its receptors, CXCR1 and CXCR2, have been observed on endothelial cells and have been shown to play a role in endothelial cell proliferation [75, 92, 93]. Recent studies indicate that CXCR1 is highly and CXCR2 is moderately expressed on human microvascular endothelial cells (HMEC), whereas human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) show low levels of CXCR1 and CXCR2 expression [93]. Neutralizing antibodies to CXCR1 and CXCR2 abrogated CXCL8-induced migration of endothelial cells, indicating that these two receptors are critical for the CXCL8 angiogenic response [81, 93]. Of these two high affinity receptors for CXCL8, the importance of CXCR2 in mediating chemokine-induced angiogenesis was demonstrated to be fundamental to CXCL8-induced neovascularization [73, 94]. The role of CXCR2 in promoting tumor-associated angiogenesis has been confirmed in other tumor systems [95, 96].

In addition to CXCL8, other members of the chemokine family have been shown to play important roles in angiogenesis. Elevated levels of CXCL5 and CXCL8 correlated with the vascularity of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [73, 97]. In a severe combined immune-deficient (SCID) mouse model system, depletion of CXCL5 resulted in the attenuation of both tumor growth, angiogenesis and spontaneous metastasis [98]. In renal cell cancer, elevated levels of CXCL1, CXCL3, CXCL5 and CXCL8 were found to be expressed in the tumor tissue and detected in the plasma, and CXCR2 was found to be expressed on endothelial cells within the tumor biopsies [96]. Thus, multiple studies mentioned above demonstrate the important role of ELR+ CXC chemokines in tumor angiogenesis.

Despite of being a non-ELR, CXC chemokine, CXCL12 is of major interest in tumor angiogenesis. Several lines of evidence indicate that CXCL12 induces endothelial cell migration, proliferation, tube formation and increases in VEGF release by endothelial cells [99–101]. Blockade of CXCL12/CXCR4 results in decreased tumor growth in vivo due to inhibition of angiogenesis in a VEGF-independent manner [102]. The source of CXCL12 that drives angiogenesis is likely to be derived from specialized stromal cells and tumor cells [103]. In a recent study, it has been suggested that CXCL12 is partly responsible for the ability of breast carcinoma-associated fibroblasts to promote angiogenesis [16]. However, the effects of CXCL12 on angiogenesis cannot be generalized to all tumor systems, as inhibition of metastasis in a model of NSCLC by CXCL12 neutralization did not show reduction of tumor angiogenesis [104]. These observations suggest that the action of CXCL12 may be tumor specific and/or may act in cooperation with other angiogenic proteins.

As mentioned above, the ELR− CXC chemokines include angiostatic members that are known to inhibit neovascularization [9, 73, 101]. The angiostatic role of these chemokines has been demonstrated in several studies. For example, CXCL10 potently inhibited CXCL8- and FGF-2-induced angiogenesis [11]. Delivery of CXCL9 or CXCL10 into tumors by injection or by genetic manipulation to express the chemokines has been shown to suppress tumor angiogenesis [105–107]. In murine cancer models, intratumoral delivery of immunotherapeutic agents correlates with increased expression of CXCL9 and/or CXCL10 [108, 109]. Clinical studies of renal carcinoma patients have also indicated that intratumoral expression of CXCL9 and CXCL10 results in decreased tumor size [110]. It has been shown that CXCR3 is expressed on endothelial cells in a cell cycle-dependent manner, and its expression mediates the angiostatic activity of CXCL9–11 [111]. Recently, it has been suggested that overexpression of CXCL10 in human prostate LNCaP cells activates CXCR3 expression and inhibits cell proliferation [112]. These findings provide definitive evidence of CXCR3-mediated angiostatic activity by angiostatic ELR− CXC chemokines. The presence of angiogenic and angiostatic regulators in the CXC chemokine family suggests that tumor angiogenesis may also be affected by the relative expression/activities of the different chemokines in the tumor microenvironment.

Recent reports demonstrate that CC chemokines can also participate in angiogenic activity in addition to members of CXC chemokine [113]. CCL2 has been added to the growing list of angiogenic modulators [113, 114]. Previous studies suggest that CCL2 indirectly stimulates angiogenesis [115, 116], however, recently it has been shown that CCL2 may also mediate angiogenic effects by acting directly on endothelial cells and increasing vascularity [114].

Fractalkine (FKN, CX3CL1), a member of the CX3C chemokine family, also belongs to the list of angiogenesis regulators [117–119]. Recent studies have suggested that the interaction of FKN and CX3CR1 contributes to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis [120, 121] and kidney diseases through the firm adhesion of leukocytes to endothelial cells [30, 122]. FKN has been also shown to participate in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis, probably by increasing the angiogenic process through endothelial cell activation [117–119]. The in vivo effect of FKN on angiogenesis has clearly shown that FKN plays a significant role in facilitating inflammatory angiogenesis by activating the GPCR [123].

Several lines of evidence suggest that a biological imbalance in the production of angiogenic and angiostatic factors, such as chemokines, contributes to the pathogenesis of several angiogenesis-dependent disorders, including cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, and psoriasis [11, 124–127]. However, the relative levels of these chemokines and their role in regulating tumor angiogenesis are not clear. More studies are needed to provide evidence that the imbalance in the expression of angiogenic or angiostatic chemokines regulates tumor angiogenesis. Based on published reports, one can predict that a shift in the balance of expression of these angiogenic and angiostatic chemokines dictates whether the tumor grows and develops metastasis or regresses. If this is correct, it will provide an opportunity to shift this imbalance in favor of angiostasis by modulating the expression of the specific chemokine by pharmacological intervention to inhibit tumor growth and metastasis.

4 Chemokines and their receptors in tumor growth and metastasis

Cancer metastasis consists of multiple, complex interactions and interdependent steps [124, 128–131] where tumor cells exploit the host responses, which are a part of normal, physiological processes, in order to grow and metastasize, and chemokines play important roles in tumor-host interaction. To begin with, chemokines can provide chemo-attractive signaling that can be critical for cellular trafficking to distant organ sites. Different tumors express several chemokine receptors, and their corresponding ligands are expressed at the site of metastasis [132–134]. It has been shown that the site of metastasis depends on the characteristics of neoplastic cells and the specific microenvironment of the secondary organ [135]. Similar to leukocyte trafficking, the secondary organ of metastasis expresses constitutive levels of chemo-attractants that can provide signaling cues for malignant cell homing. The role of chemokines in organ specific metastasis was initially suggested in breast cancer. It was demonstrated that CCR7 and CXCR4 that are highly expressed in breast cancer cells determine the invasion and organ specificity of breast cancer metastasis [133] The ligands CCL21 and CXCL12 for these receptors exhibit higher expression in the organs (lung and liver) that are preferred sites for breast cancer metastasis [133]. Recently, it has been suggested that osteoclasts may promote metastasis of lung cancer cells expressing CCR4 to the bone marrow by producing its ligand CCL22 [136]. Stimulation of osteoclast-like cells with CCR4 results in up-regulation of its ligand, CCL22. In addition, it has been demonstrated that a human lung cancer cell line, which expresses CCR4 metastasizes to bone when injected intravenously into NK cell-depleted SCID mice [136]. Together, the above data supports that the expression of chemokine ligands or their receptors in the organ environment or by malignant cells plays a major role in organ-specific metastasis.

CXCR4 appears to be the major chemokine receptor expressed on cancer cells. The expression of CXCR4 has been reported in more than 23 different types of cancer cell [137]. The accumulating evidence suggests that CXCR4 is an important regulator of breast cancer metastasis and can be predictive of lymph node metastasis [138–140]. In experimental studies, treatment of CXCR4-expressing breast cancer cells with neutralizing anti-CXCR4 antibody reduced metastasis to lung in a mouse model [133]. Gene array analysis of human breast cancer myoepithelial cells and myofibroblasts demonstrated up-regulation of both CXCR4 and CXCL12 which serve to enhance migration and invasion [141]. CXCR4 expression also mediates organ-specific metastasis of pancreatic cancer cells and a strong association of CXCR4 with advanced pancreatic cancer has also been suggested [142, 143]. In vitro stimulation of CXCR4-positive cancer cells with CXCL12 resulted in directed migration/invasion of ovarian cancer cells [144]. Stimulation with CXCL12 also up-regulated integrin expression and facilitated adhesion in lung cancer cells [145]. Furthermore, it has been shown that the expression of CXCR4 on human renal cells carcinoma (RCC) correlates with their metastatic ability in both heterotopic and orthotopic SCID mouse models [146]. Treatment with specific anti-CXCL12 antibodies markedly abrogated metastasis of RCC expressing high levels of CXCL12 to target organs in an orthotopic model of RCC, without significant changes in tumor cell proliferation, apoptosis, or tumor-associated angiogenesis [146]. The above findings support the notion that the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis plays a critical role in regulating tumor growth and metastasis.

In addition, the clinical relevance of CXCR4 expression has been demonstrated in various types of cancers. In oesophageal cancer and melanoma, CXCR4 expression is associated with poor clinical outcome [147, 148]. In breast cancer, CXCR4 expression predicted lymph node metastasis [138]. Patients with high CXCR4 expression in NSCLC, colorectal or prostate cancer were more prone to metastasis [149–151]. The expression of CXCR4 in nasopharyngeal carcinoma and osteosarcoma is also associated with metastasis [152, 153]. In colorectal cancer, CXCR4 expression in primary tumors demonstrated significant association with recurrence, survival, and liver metastasis [154]. In contrast, a study of neuroblastoma patients found that, although neuroblastoma cells expressed CXCR4, this was not functional [155] and a study of approximately 300 breast cancer patients found that expression of CXCR4 was not associated with metastasis [156]. Above data strongly suggest the role of CXCR4 in regulating the progression of tumor cells to metastasize; however, additional investigations are needed to resolve the ambiguities in different studies.

CXCL8, a potent chemoattractant, has been demonstrated to contribute to human cancer progression through its potential function as a mitogenic and angiogenic factor. Elevated levels of CXCL8 have been detected in variety of tumors, such as ovarian carcinoma [157], NSCLC [158], metastatic melanoma [159], and colon carcinoma [160]. Studies from our laboratory and others suggest that the expression of CXCL8 correlates positively with disease progression [161–164].

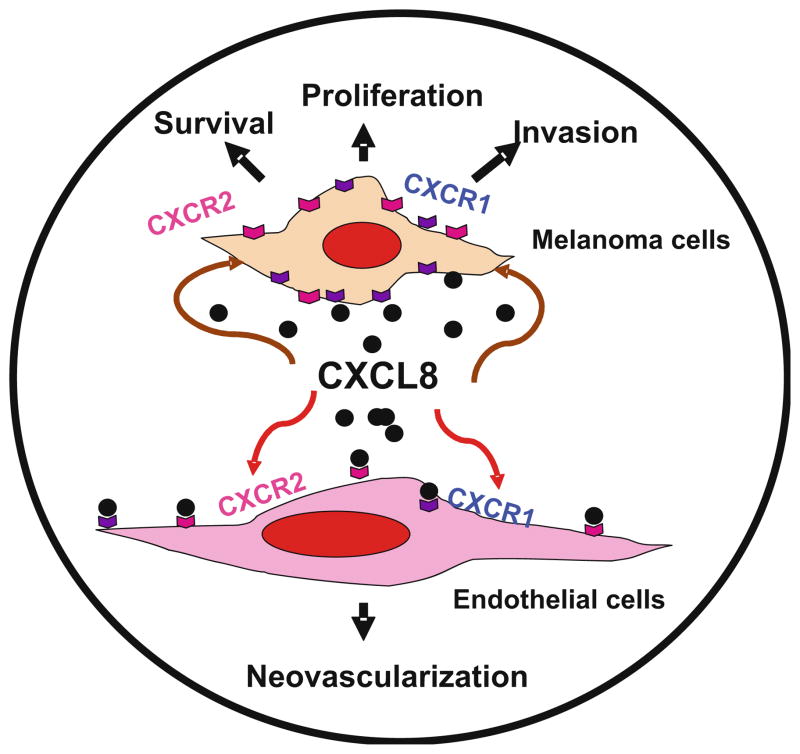

A concomitant up-regulation of one of the two putative CXCL8 receptors has been reported in human melanoma specimens. Analysis of CXCR1 in human melanoma specimens from different Clark levels demonstrated that it was expressed ubiquitously in all Clark levels. In contrast, CXCR2 was expressed predominantly by higher grade melanoma tumors and metastases, suggesting an association between expression of CXCL8 and CXCR2 with vessel density in advanced lesions and metastasis [159]. In fact, the effect of CXCL8 can be mediated by CXCR1 and CXCR2, with CXCR1 being a selective receptor for CXCL8 [94]. Together, these data implicate that CXCL8 can directly modulate growth and the metastatic phenotype of cancer cells (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

CXCL-8 in melanoma growth, angiogenesis and metastasis. CXCL-8 functions as an autocrine/paracrine growth factor for malignant melanoma cells [200–202], up-regulates expression of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 and MMP-9, regulates the migratory and invasive potential of melanoma cells and functions as a paracrine and autocrine angiogenic factor [200, 203–208]

CCR7 is another chemokine receptor highly expressed by several tumor types. CCR7 plays a critical role in lymphocyte and dendritic cell trafficking into and within lymph nodes. Human cancer cells from malignant breast, gastric, oesophageal, NSCLC, squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck and colorectal carcinomas express functional CCR7 [133, 165–169]. Cancer cells that over-express CCR7 can migrate towards its ligand CCL21, which is strongly expressed in lymph nodes [167, 170]. It has been reported that when CCR7 was overexpressed in a murine melanoma cell line, metastasis to lymph nodes was increased in vivo [171]. Recently, it has been reported that CCR7 activation on thyroid carcinoma cell by CCL21 favors tissue invasion and cell proliferation, and therefore may promote thyroid carcinoma growth and lymph node metastasis [172]. CCR7 is a potential marker to predict metastasis in breast and colorectal cancer and is correlated with disease progression [138, 166]. In addition, patients with oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas that express CCR7 have lower survival rates than those with CCR7-negative tumors [173].

In addition, there are many more chemokines that have been detected in various cancers and are known to play role in metastasis. Recently, CCL2 was also shown to be extremely important in tumorigenesis and bone metastasis of several solid tumors [174]. The expression of CCR2 correlates with prostate cancer progression [175] and CCR3 in human renal cell carcinoma [176]. Co-expression of CCR4 and CCR10, the known pair of skin-homing chemokine receptors, may play an important role in adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL) invasion into the skin [177]. CCL5 and its receptor CCR5 has been detected on prostate cancer cell lines [178]. CCR6 and its ligand have been shown to be involved in colorectal cancer and its metastasis [179]; CCR9 on prostate and melanoma cells [180, 181]; and CCR10 on melanoma cells [133]. The expression of CCR10 and CCL27 in human melanomas increases the ability of neoplastic cells to grow, invade and disseminate to lymph node [182]. Expression of CXCR5 in carcinomas seems highly unlikely, but recently it has been shown that CXCR5 is expressed by colon carcinoma cells and promotes tumor growth and metastasis to liver [183]. In addition, prostate cancer cells express CX3CR1 and stimulation with its ligand CX3CL1 resulted in increased adhesion and migration [184].

It is possible that the cancer cell can exploit interferon-inducible chemokines for their own propagation, survival and metastasis. For example, CXCL9 and CXCL10 induce the migration and invasion of melanoma cell lines and multiple myeloma cells [185–187]. CXCR3, the receptor for CXCL9 and CXCL10 was shown to be expressed by cancer cells of solid tumors, such as breast tumor cells, renal carcinoma cells and melanoma cells [185, 188–190]. A direct role for CXCR3 in inducing tumor cell migration to metastatic sites was suggested by observations showing that the expression of this chemokine receptor by melanoma cells is causally involved in metastasis to lymph nodes [187]. Recently, it has also been demonstrated that CXCR3 plays a critical role in colon cancer cell metastasis to lymph nodes by inducing diverse cellular effects [191]. These data suggest that anti-malignant or pro-malignant behavior of these chemokines (such as CXCL9 and CXCL10) would be in part dictated by their receptor expression by the cancer cell.

Overall, the aberrant expression of chemokines and their receptors may be a common feature of various epithelial cancers. Although, the functional significance of some of these chemokines is yet to be elucidated, we can contemplate that the expression of certain chemokines and their receptors plays a key role in dictating the fate of developing tumors and their ability to metastasize to certain preferred organ sites.

5 Chemokine receptor signaling in tumor growth and metastasis

Despite the recent advances in our understanding of chemotaxis, the precise mechanisms through which tumor and endothelial cells respond to chemokines remains unclear. A conformational change in the GPCR trans-membrane domain is believed to be responsible for receptor activation. The initial events in chemokine-induced signal transduction determine the outcome of the response and must take place in the proximity of the receptor. Here we will describe a simple schematic which is not meant to be complete, but to present the most evident effectors in chemokine receptor signaling. Activation of the receptor by a chemokine ligand induces the exchange in the α-subunit of the G-protein from GDP to the GTP bound state dissociating the α from β and γ from G-protein subunits. These subunits activate phospholipase (PL) Cβ1 and Cβ2, followed by hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4, 5-biphosphate (PIP2), which leads to formation of inositol triphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG) with a subsequent increase in intracellular Ca2+ mobilization [33]. Although chemokine receptors lack tyrosine kinase activity, they can stimulate the phosphorylation of cytoskeletal proteins, p130 Cas and paxillin [192] and induce activation of the related focal adhesion kinases (FAKs) (also known as Pyk2 and CAKβ) [193], mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPK) (ERK1/2, p38 and JNK) [193], phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) (193) and Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) [194, 195]. Extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK1 and ERK2) also termed p44/42 kinases, are important mediators of growth and other cell signaling [196, 197]. Because most of the G protein coupled receptors can activate a variety of effector pathways via various G protein subunits, considerable heterogeneity exists in signaling pathways leading to ERK1/2 phosphorylation and subsequent activation of transcription factors [33]. In addition, recent data suggests that signals dependent on G proteins mediated through Rho and Rac pathways result in actin polymerization, reconstitution of adhesion molecules and other cellular components leading to cell migration [198].

Chemokine-mediated signal transduction is more complex especially if one takes into account the cross-regulatory mechanism(s) of the integrated network [33, 199]. The analysis of signaling events further downstream from receptor activation is more complicated because of the potential contributions from various pathways since many pathways are shared by different receptor systems. For example, binding of CXCL8 to its receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 can initiate many overlapping responses and might be mediated by diverse signal transduction mediators leading to distinct responses such as cell proliferation, survival and migration/invasion.

6 Conclusion and perspective

Overexpression of chemokines and chemokine receptors appears to be a hallmark of cancer. Furthermore, identifying the specific networks of chemokines and their receptors and understanding the effect of chemokines and their receptors expression on local immune response, angiogenesis and their interaction with other factors at the tumor milieu will reveal novel approaches for restricting tumor growth and metastasis.

The accumulating evidence resulting from the experimental studies points towards a critical role of chemokines and their receptors in cancer progression and metastasis. Many retrospective studies have now demonstrated that the expression of various chemokines and their receptors is associated with poor prognosis. This advocates that the measurement of chemokines and their receptor expression in tumor samples has the potential of becoming a biomarker of relative tumor aggressiveness. This will be helpful in selecting appropriate treatments for certain cancer patients. From the scientific perspective, we foresee that a better understanding of the biological and molecular mechanisms of chemokine-dependent regulation of cellular phenotypes associated with tumor growth, angiogenesis and metastasis, will identify the cellular and molecular targets, which might be important in the distinct functional interactions of chemokines with their receptors on malignant cells and endothelial cells. An understanding of the mechanism(s) regulating modulation of chemokine-receptor pathways will be critical in prognosis and designing effective strategies for the development of novel targeted molecular therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants CA72781 from National Institutes of Health and Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services and Nebraska Research Initiative.

References

- 1.Fidler IJ. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: The ‘seed and soil’ hypothesis revisited. Nature Review Cancer. 2003;3(6):453–458. doi: 10.1038/nrc1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Locati M, Otero K, Schioppa T, Signorelli P, Perrier P, Baviera S, et al. The chemokine system: Tuning and shaping by regulation of receptor expression and coupling in polarized responses. Allergy. 2002;57(11):972–982. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2002.02166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy PM, Baggiolini M, Charo IF, Hebert CA, Horuk R, Matsushima K, et al. International union of pharmacology. XXII. Nomenclature for chemokine receptors. Pharmacological Reviews. 2000;52(1):145–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zlotnik A, Yoshie O. Chemokines: a new classification system and their role in immunity. Immunity. 2000;12(2):121–127. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy PM. International Union of Pharmacology. XXX. Update on chemokine receptor nomenclature. Pharmacological Reviews. 2002;54(2):227–229. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baggiolini M, Dewald B, Moser B. Human chemokines: An update. Annual Review of Immunology. 1997;15:675–705. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strieter RM, Polverini PJ, Kunkel SL, Arenberg DA, Burdick MD, Kasper J, et al. The functional role of the ELR motif in CXC chemokine-mediated angiogenesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270(45):27348–27357. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.27348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strieter RM, Burdick MD, Mestas J, Gomperts B, Keane MP, Belperio JA. Cancer CXC chemokine networks and tumour angiogenesis. European Journal of Cancer. 2006;42(6):768–778. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belperio JA, Keane MP, Arenberg DA, Addison CL, Ehlert JE, Burdick MD, et al. CXC chemokines in angiogenesis. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2000;68(1):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luster AD. Chemokines–chemotactic cytokines that mediate inflammation. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;338(7):436–445. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802123380706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strieter RM, Kunkel SL, Arenberg DA, Burdick MD, Polverini PJ. Interferon gamma-inducible protein 10 (IP-10), a member of the C-X-C chemokine family, is an inhibitor of angiogenesis. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1995;210(1):51–57. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maione TE, Gray GS, Petro J, Hunt AJ, Donner AL, Bauer SI, et al. Inhibition of angiogenesis by recombinant human platelet factor-4 and related peptides. Science. 1990;247(4938):77–79. doi: 10.1126/science.1688470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagpal ML, Chen Y, Lin T. Effects of overexpression of CXCL10 (cytokine-responsive gene-2) on MA-10 mouse Leydig tumor cell steroidogenesis and proliferation. Journal of Endocrinology. 2004;183(3):585–594. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.05795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagasawa T, Nakajima T, Tachibana K, Iizasa H, Bleul CC, Yoshie O, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of a murine pre-B-cell growth-stimulating factor/stromal cell-derived factor 1 receptor, a murine homolog of the human immunodeficiency virus 1 entry coreceptor fusin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93(25):14726–14729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mirshahi F, Pourtau J, Li H, Muraine M, Trochon V, Legrand E, et al. SDF-1 activity on microvascular endothelial cells: Consequences on angiogenesis in in vitro and in vivo models. Thrombosis Research. 2000;99(6):587–594. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(00)00292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orimo A, Gupta PB, Sgroi DC, renzana-Seisdedos F, Delaunay T, Naeem R, et al. Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through elevated SDF-1/CXCL12 secretion. Cell. 2005;121(3):335–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salcedo R, Wasserman K, Young HA, Grimm MC, Howard OM, Anver MR, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor induce expression of CXCR4 on human endothelial cells: in vivo neovascularization induced by stromal-derived factor-1alpha. American Journal of Pathology. 1999;154(4):1125–1135. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65365-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tachibana K, Hirota S, Iizasa H, Yoshida H, Kawabata K, Kataoka Y, et al. The chemokine receptor CXCR4 is essential for vascularization of the gastrointestinal tract. Nature. 1998;393(6685):591–594. doi: 10.1038/31261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baggiolini M, Dewald B, Moser B. Interleukin-8 and related chemotactic cytokines–CXC and CC chemokines. Advances in Immunology. 1994;55:97–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bischoff SC, Krieger M, Brunner T, Rot A, von TV, Baggiolini M, et al. RANTES and related chemokines activate human basophil granulocytes through different G protein-coupled receptors. European Journal of Immunology. 1993;23(3):761–767. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dahinden CA, Geiser T, Brunner T, von TV, Caput D, Ferrara P, et al. Monocyte chemotactic protein 3 is a most effective basophil- and eosinophil-activating chemokine. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1994;179(2):751–756. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia-Zepeda EA, Rothenberg ME, Ownbey RT, Celestin J, Leder P, Luster AD. Human eotaxin is a specific chemoattractant for eosinophil cells and provides a new mechanism to explain tissue eosinophilia. Nature Medicine. 1996;2(4):449–456. doi: 10.1038/nm0496-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imai T, Yoshida T, Baba M, Nishimura M, Kakizaki M, Yoshie O. Molecular cloning of a novel T cell-directed CC chemokine expressed in thymus by signal sequence trap using Epstein-Barr virus vector. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(35):21514–21521. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.35.21514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jose PJ, Griffiths-Johnson DA, Collins PD, Walsh DT, Moqbel R, Totty NF, et al. Eotaxin: A potent eosinophil chemoattractant cytokine detected in a guinea pig model of allergic airways inflammation. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1994;179(3):881–887. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.3.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kameyoshi Y, Dorschner A, Mallet AI, Christophers E, Schroder JM. Cytokine RANTES released by thrombin-stimulated platelets is a potent attractant for human eosinophils. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1992;176(2):587–592. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.2.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ponath PD, Qin S, Ringler DJ, Clark-Lewis I, Wang J, Kassam N, et al. Cloning of the human eosinophil chemoattractant, eotaxin. Expression, receptor binding, and functional properties suggest a mechanism for the selective recruitment of eosinophils. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1996;97(3):604–612. doi: 10.1172/JCI118456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rot A, Krieger M, Brunner T, Bischoff SC, Schall TJ, Dahinden CA. RANTES and macrophage inflammatory protein 1 alpha induce the migration and activation of normal human eosinophil granulocytes. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1992;176(6):1489–1495. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.6.1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelner GS, Kennedy J, Bacon KB, Kleyensteuber S, Largaespada DA, Jenkins NA, et al. Lymphotactin: A cytokine that represents a new class of chemokine. Science. 1994;266(5189):1395–1399. doi: 10.1126/science.7973732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bazan JF, Bacon KB, Hardiman G, Wang W, Soo K, Rossi D, et al. A new class of membrane-bound chemokine with a CX3C motif. Nature. 1997;385(6617):640–644. doi: 10.1038/385640a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Segerer S, Hughes E, Hudkins KL, Mack M, Goodpaster T, Alpers CE. Expression of the fractalkine receptor (CX3CR1) in human kidney diseases. Kidney International. 2002;62(2):488–495. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Umehara H, Imai T. Role of fractalkine in leukocyte adhesion and migration and in vascular injury. Drug News & Perspectives. 2001;14(8):460–464. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2001.14.8.858415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pan Y, Lloyd C, Zhou H, Dolich S, Deeds J, Gonzalo JA, et al. Neurotactin, a membrane-anchored chemokine upregulated in brain inflammation. Nature. 1997;387(6633):611–617. doi: 10.1038/42491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thelen M. Dancing to the tune of chemokines. Nature Immunology. 2001;2(2):129–134. doi: 10.1038/84224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee J, Horuk R, Rice GC, Bennett GL, Camerato T, Wood WI. Characterization of two high affinity human interleukin-8 receptors. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267(23):16283–16287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wuyts A, Proost P, Lenaerts JP, Ben-Baruch A, Van DJ, Wang JM. Differential usage of the CXC chemokine receptors 1 and 2 by interleukin-8, granulocyte chemotactic protein-2 and epithelial-cell-derived neutrophil attractant-78. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1998;255(1):67–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2550067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baggiolini M, Loetscher P. Chemokines in inflammation and immunity. Immunology Today. 2000;21(9):418–420. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01672-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Locati M, Murphy PM. Chemokines and chemokine receptors: biology and clinical relevance in inflammation and AIDS. Annual Review of Medicine. 1999;50:425–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.50.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cole KE, Strick CA, Paradis TJ, Ogborne KT, Loetscher M, Gladue RP, et al. Interferon-inducible T cell alpha chemoattractant (I-TAC): a novel non-ELR CXC chemokine with potent activity on activated T cells through selective high affinity binding to CXCR3. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1998;187(12):2009–2021. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.12.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farber JM. Mig and IP-10: CXC chemokines that target lymphocytes. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 1997;61(3):246–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Loetscher M, Loetscher P, Brass N, Meese E, Moser B. Lymphocyte-specific chemokine receptor CXCR3: Regulation, chemokine binding and gene localization. European Journal of Immunology. 1998;28(11):3696–705. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199811)28:11<3696::AID-IMMU3696>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feng Y, Broder CC, Kennedy PE, Berger EA. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 1996;272(5263):872–877. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oberlin E, Amara A, Bachelerie F, Bessia C, Virelizier JL, renzana-Seisdedos F, et al. The CXC chemokine SDF-1 is the ligand for LESTR/fusin and prevents infection by T-cell-line-adapted HIV-1. Nature. 1996;382(6594):833–835. doi: 10.1038/382833a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Legler DF, Loetscher M, Roos RS, Clark-Lewis I, Baggiolini M, Moser B. B cell-attracting chemokine 1, a human CXC chemokine expressed in lymphoid tissues, selectively attracts B lymphocytes via BLR1/CXCR5. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1998;187(4):655–660. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.4.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deng HK, Unutmaz D, KewalRamani VN, Littman DR. Expression cloning of new receptors used by simian and human immunodeficiency viruses. Nature. 1997;388(6639):296–300. doi: 10.1038/40894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matloubian M, David A, Engel S, Ryan JE, Cyster JG. A transmembrane CXC chemokine is a ligand for HIV-coreceptor Bonzo. Nature Immunology. 2000;1(4):298–304. doi: 10.1038/79738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berkhout TA, Gohil J, Gonzalez P, Nicols CL, Moores KE, Macphee CH, et al. Selective binding of the truncated form of the chemokine CKbeta8 (25–99) to CC chemokine receptor 1(CCR1) Biochemical Pharmacology. 2000;59(5):591–596. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00354-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gong JH, Uguccioni M, Dewald B, Baggiolini M, Clark-Lewis I. RANTES and MCP-3 antagonists bind multiple chemokine receptors. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(18):10521–10527. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hwang J, Son KN, Kim CW, Ko J, Na DS, Kwon BS, et al. Human CC chemokine CCL23, a ligand for CCR1, induces endothelial cell migration and promotes angiogenesis. Cytokine. 2005;30(5):254–263. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2005.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Neote K, Darbonne W, Ogez J, Horuk R, Schall TJ. Identification of a promiscuous inflammatory peptide receptor on the surface of red blood cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268(17):12247–12249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsou CL, Gladue RP, Carroll LA, Paradis T, Boyd JG, Nelson RT, et al. Identification of C-C chemokine receptor 1 (CCR1) as the monocyte hemofiltrate C-C chemokine (HCC)-1 receptor. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1998;188(3):603–608. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.3.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Charo IF, Myers SJ, Herman A, Franci C, Connolly AJ, Coughlin SR. Molecular cloning and functional expression of two monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 receptors reveals alternative splicing of the carboxyl-terminal tails. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91(7):2752–2756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moore UM, Kaplow JM, Pleass RD, Castro SW, Naik K, Lynch CN, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-2 is a potent agonist of CCR2B. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 1997;62(6):911–915. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.6.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stellato C, Collins P, Ponath PD, Soler D, Newman W, La RG, et al. Production of the novel C-C chemokine MCP-4 by airway cells and comparison of its biological activity to other C-C chemokines. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1997;99(5):926–936. doi: 10.1172/JCI119257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Forssmann U, Uguccioni M, Loetscher P, Dahinden CA, Langen H, Thelen M, et al. Eotaxin-2, a novel CC chemokine that is selective for the chemokine receptor CCR3, and acts like eotaxin on human eosinophil and basophil leukocytes. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1997;185(12):2171–2176. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.12.2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Forssmann U, Hartung I, Balder R, Fuchs B, Escher SE, Spodsberg N, et al. n-Nonanoyl-CC chemokine ligand 14, a potent CC chemokine ligand 14 analogue that prevents the recruitment of eosinophils in allergic airway inflammation. Journal of Immunology. 2004;173(5):3456–3466. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Uguccioni M, Mackay CR, Ochensberger B, Loetscher P, Rhis S, LaRosa GJ, et al. High expression of the chemokine receptor CCR3 in human blood basophils. Role in activation by eotaxin, MCP-4, and other chemokines. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1997;100(5):1137–1143. doi: 10.1172/JCI119624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Youn BS, Zhang SM, Lee EK, Park DH, Broxmeyer HE, Murphy PM, et al. Molecular cloning of leukotactin-1: a novel human beta-chemokine, a chemoattractant for neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes, and a potent agonist at CC chemokine receptors 1 and 3. Journal of Immunology. 1997;159(11):5201–5205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Imai T, Baba M, Nishimura M, Kakizaki M, Takagi S, Yoshie O. The T cell-directed CC chemokine TARC is a highly specific biological ligand for CC chemokine receptor 4. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(23):15036–15042. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.15036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Imai T, Chantry D, Raport CJ, Wood CL, Nishimura M, Godiska R, et al. Macrophage-derived chemokine is a functional ligand for the CC chemokine receptor 4. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(3):1764–1768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Littman DR. Chemokine receptors: Keys to AIDS pathogenesis. Cell. 1998;93(5):677–680. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81429-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Blanpain C, Migeotte I, Lee B, Vakili J, Doranz BJ, Govaerts C, et al. CCR5 binds multiple CC-chemokines: MCP-3 acts as a natural antagonist. Blood. 1999;94(6):1899–1905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Baba M, Imai T, Nishimura M, Kakizaki M, Takagi S, Hieshima K, et al. Identification of CCR6, the specific receptor for a novel lymphocyte-directed CC chemokine LARC. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(23):14893–14898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yoshida R, Imai T, Hieshima K, Kusuda J, Baba M, Kitaura M, et al. Molecular cloning of a novel human CC chemokine EBI1-ligand chemokine that is a specific functional ligand for EBI1, CCR7. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(21):13803–13809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tiffany HL, Lautens LL, Gao JL, Pease J, Locati M, Combadiere C, et al. Identification of CCR8: a human monocyte and thymus receptor for the CC chemokine I-309. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1997;186(1):165–170. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.1.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zaballos A, Gutierrez J, Varona R, Ardavin C, Marquez G. Cutting edge: Identification of the orphan chemokine receptor GPR-9-6 as CCR9, the receptor for the chemokine TECK. Journal of Immunology. 1999;162(10):5671–5675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bonini JA, Steiner DF. Molecular cloning and expression of a novel rat CC-chemokine receptor (rCCR10rR) that binds MCP-1 and MIP-1beta with high affinity. DNA and Cell Biology. 1997;16(9):1023–1030. doi: 10.1089/dna.1997.16.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang W, Soto H, Oldham ER, Buchanan ME, Homey B, Catron D, et al. Identification of a novel chemokine (CCL28), which binds CCR10 (GPR2) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(29):22313–22323. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001461200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mantovani A. The chemokine system: redundancy for robust outputs. Immunology Today. 1999;20(6):254–257. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01469-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Folkman J, Cotran R. Relation of vascular proliferation to tumor growth. International Review of Experimental Pathology. 1976;16:207–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis. Advances in Cancer Research. 1985;43:175–203. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60946-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Folkman J, Klagsbrun M. Vascular physiology. A family of angiogenic peptides. Nature. 1987;329(6141):671–672. doi: 10.1038/329671a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leibovich SJ, Wiseman DM. Macrophages, wound repair and angiogenesis. Progress in Clinical and Biological Research. 1988;266:131–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Strieter RM, Belperio JA, Phillips RJ, Keane MP. CXC chemokines in angiogenesis of cancer. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2004;14(3):195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hu DE, Hori Y, Fan TP. Interleukin-8 stimulates angiogenesis in rats. Inflammation. 1993;17(2):135–143. doi: 10.1007/BF00916100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Koch AE, Polverini PJ, Kunkel SL, Harlow LA, DiPietro LA, Elner VM, et al. Interleukin-8 as a macrophage-derived mediator of angiogenesis. Science. 1992;258(5089):1798–1801. doi: 10.1126/science.1281554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Norrby K. Interleukin-8 and de novo mammalian angiogenesis. Cell Proliferation. 1996;29(6):315–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.1996.tb01583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Strieter RM, Kunkel SL, Elner VM, Martonyi CL, Koch AE, Polverini PJ, et al. Interleukin-8. A corneal factor that induces neovascularization. American Journal of Pathology. 1992;141(6):1279–1284. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yoshida S, Ono M, Shono T, Izumi H, Ishibashi T, Suzuki H, et al. Involvement of interleukin-8, vascular endothelial growth factor, and basic fibroblast growth factor in tumor necrosis factor alpha-dependent angiogenesis. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1997;17(7):4015–4023. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.7.4015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Li A, Dubey S, Varney ML, Dave BJ, Singh RK. IL-8 directly enhanced endothelial cell survival, proliferation, and matrix metalloproteinases production and regulated angiogenesis. Journal of Immunology. 2003;170(6):3369–3376. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shono T, Ono M, Izumi H, Jimi SI, Matsushima K, Okamoto T, et al. Involvement of the transcription factor NF-kappaB in tubular morphogenesis of human micro-vascular endothelial cells by oxidative stress. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1996;16(8):4231–4239. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Li A, Varney ML, Valasek J, Godfrey M, Dave BJ, Singh RK. Autocrine role of interleukin-8 in induction of endothelial cell proliferation, survival, migration and MMP-2 production and angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2005;8(1):63–71. doi: 10.1007/s10456-005-5208-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Inoue K, Slaton JW, Eve BY, Kim SJ, Perrotte P, Balbay MD, et al. Interleukin 8 expression regulates tumorigenicity and metastases in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2000;6(5):2104–2119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Luca M, Huang S, Gershenwald JE, Singh RK, Reich R, Bar-Eli M. Expression of interleukin-8 by human melanoma cells up-regulates MMP-2 activity and increases tumor growth and metastasis. American Journal of Pathology. 1997;151(4):1105–1113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.McCawley LJ, Matrisian LM. Matrix metalloproteinases: multifunctional contributors to tumor progression. Molecular Medicine Today. 2000;6(4):149–156. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(00)01686-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xie K. Interleukin-8 and human cancer biology. Cytokine and Growth Factor Reviews. 2001;12(4):375–391. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(01)00016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yoneda J, Kuniyasu H, Crispens MA, Price JE, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ. Expression of angiogenesis-related genes and progression of human ovarian carcinomas in nude mice. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1998;90(6):447–454. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.6.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Benoy IH, Salgado R, Van DP, Geboers K, Van ME, Scharpe S, et al. Increased serum interleukin-8 in patients with early and metastatic breast cancer correlates with early dissemination and survival. Clinical Cancer Research. 2004;10(21):7157–7162. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Veltri RW, Miller MC, Zhao G, Ng A, Marley GM, Wright GL, Jr, et al. Interleukin-8 serum levels in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer. Urology. 1999;53(1):139–147. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00455-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Aalinkeel R, Nair MP, Sufrin G, Mahajan SD, Chadha KC, Chawda RP, et al. Gene expression of angiogenic factors correlates with metastatic potential of prostate cancer cells. Cancer Research. 2004;64(15):5311–5321. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-2506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lehrer S, Diamond EJ, Mamkine B, Stone NN, Stock RG. Serum interleukin-8 is elevated in men with prostate cancer and bone metastases. Technology in Cancer Research and Treatment. 2004;3(5):411. doi: 10.1177/153303460400300501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Uehara H, Troncoso P, Johnston D, Bucana CD, Dinney C, Dong Z, et al. Expression of interleukin-8 gene in radical prostatectomy specimens is associated with advanced pathologic stage. Prostate. 2005;64(1):40–49. doi: 10.1002/pros.20223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Murdoch C, Monk PN, Finn A. Cxc chemokine receptor expression on human endothelial cells. Cytokine. 1999;11(9):704–712. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1998.0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Salcedo R, Resau JH, Halverson D, Hudson EA, Dambach M, Powell D, et al. Differential expression and responsiveness of chemokine receptors (CXCR1–3) by human microvascular endothelial cells and umbilical vein endothelial cells. FASEB Journal 2000. 2000;14(13):2055–2064. doi: 10.1096/fj.99-0963com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Addison CL, Daniel TO, Burdick MD, Liu H, Ehlert JE, Xue YY, et al. The CXC chemokine receptor 2, CXCR2, is the putative receptor for ELR + CXC chemokine-induced angiogenic activity. Journal of Immunology. 2000;165(9):5269–5277. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Keane MP, Belperio JA, Xue YY, Burdick MD, Strieter RM. Depletion of CXCR2 inhibits tumor growth and angiogenesis in a murine model of lung cancer. Journal of Immunology. 2004;172(5):2853–2860. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mestas J, Burdick MD, Reckamp K, Pantuck A, Figlin RA, Strieter RM. The role of CXCR2/CXCR2 ligand biological axis in renal cell carcinoma. Journal of Immunology. 2005;175(8):5351–5357. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Numasaki M, Watanabe M, Suzuki T, Takahashi H, Nakamura A, McAllister F, et al. IL-17 enhances the net angiogenic activity and in vivo growth of human non-small cell lung cancer in SCID mice through promoting CXCR-2-dependent angiogenesis. Journal of Immunology. 2005;175(9):6177–6189. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.6177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Arenberg DA, Keane MP, DiGiovine B, Kunkel SL, Morris SB, Xue YY, et al. Epithelial-neutrophil activating peptide (ENA-78) is an important angiogenic factor in non-small cell lung cancer. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1998;102(3):465–472. doi: 10.1172/JCI3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kanda S, Mochizuki Y, Kanetake H. Stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha induces tube-like structure formation of endothelial cells through phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(1):257–262. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204771200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Neuhaus T, Stier S, Totzke G, Gruenewald E, Fronhoffs S, Sachinidis A, et al. Stromal cell-derived factor 1alpha (SDF-1alpha) induces gene-expression of early growth response-1 (Egr-1) and VEGF in human arterial endothelial cells and enhances VEGF induced cell proliferation. Cell Proliferation. 2003;36(2):75–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2184.2003.00262.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Salcedo R, Oppenheim JJ. Role of chemokines in angiogenesis: CXCL12/SDF-1 and CXCR4 interaction, a key regulator of endothelial cell responses. Microcirculation. 2003;10(3–4):359–370. doi: 10.1038/sj.mn.7800200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Guleng B, Tateishi K, Ohta M, Kanai F, Jazag A, Ijichi H, et al. Blockade of the stromal cell-derived factor-1/CXCR4 axis attenuates in vivo tumor growth by inhibiting angiogenesis in a vascular endothelial growth factor-independent manner. Cancer Research. 2005;65(13):5864–5871. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Barbero S, Bonavia R, Bajetto A, Porcile C, Pirani P, Ravetti JL, et al. Stromal cell-derived factor 1alpha stimulates human glioblastoma cell growth through the activation of both extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 and Akt. Cancer Research. 2003;63(8):1969–1974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Phillips RJ, Burdick MD, Lutz M, Belperio JA, Keane MP, Strieter RM. The stromal derived factor-1/CXCL12-CXC chemokine receptor 4 biological axis in non-small cell lung cancer metastases. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2003;167(12):1676–1686. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200301-071OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Arenberg DA, Kunkel SL, Polverini PJ, Morris SB, Burdick MD, Glass MC, et al. Interferon-gamma-inducible protein 10 (IP-10) is an angiostatic factor that inhibits human non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) tumorigenesis and spontaneous metastases. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1996;184(3):981–992. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sgadari C, Angiolillo AL, Cherney BW, Pike SE, Farber JM, Koniaris LG, et al. Interferon-inducible protein-10 identified as a mediator of tumor necrosis in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93(24):13791–13796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sgadari C, Farber JM, Angiolillo AL, Liao F, Teruya-Feldstein J, Burd PR, et al. Mig, the monokine induced by interferon-gamma, promotes tumor necrosis in vivo. Blood. 1997;89(8):2635–2643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Dorsey R, Kundu N, Yang Q, Tannenbaum CS, Sun H, Hamilton TA, et al. Immunotherapy with interleukin-10 depends on the CXC chemokines inducible protein-10 and monokine induced by IFN-gamma. Cancer Research. 2002;62(9):2606–2610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ruehlmann JM, Xiang R, Niethammer AG, Ba Y, Pertl U, Dolman CS, et al. MIG (CXCL9) chemokine gene therapy combines with antibody-cytokine fusion protein to suppress growth and dissemination of murine colon carcinoma. Cancer Research. 2001;61(23):8498–8503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kondo T, Ito F, Nakazawa H, Horita S, Osaka Y, Toma H. High expression of chemokine gene as a favorable prognostic factor in renal cell carcinoma. Journal of Urology. 2004;171(6 Pt 1):2171–2175. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000127726.25609.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Romagnani P, Annunziato F, Lasagni L, Lazzeri E, Beltrame C, Francalanci M, et al. Cell cycle-dependent expression of CXC chemokine receptor 3 by endothelial cells mediates angiostatic activity. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2001;107(1):53–63. doi: 10.1172/JCI9775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Nagpal ML, Davis J, Lin T. Overexpression of CXCL10 in human prostate LNCaP cells activates its receptor (CXCR3) expression and inhibits cell proliferation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2006;1762(9):811–818. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Salcedo R, Ponce ML, Young HA, Wasserman K, Ward JM, Kleinman HK, et al. Human endothelial cells express CCR2 and respond to MCP-1: Direct role of MCP-1 in angiogenesis and tumor progression. Blood. 2000;96(1):34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hong KH, Ryu J, Han KH. Monocyte chemo-attractant protein-1-induced angiogenesis is mediated by vascular endothelial growth factor-A. Blood. 2005;105(4):1405–1407. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Goede V, Brogelli L, Ziche M, Augustin HG. Induction of inflammatory angiogenesis by monocyte chemo-attractant protein-1. International Journal of Cancer. 1999;82(5):765–770. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990827)82:5<765::aid-ijc23>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Leung SY, Wong MP, Chung LP, Chan AS, Yuen ST. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression and macrophage infiltration in gliomas. Acta Neuropathologica (Berlin) 1997;93(5):518–527. doi: 10.1007/s004010050647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Blaschke S, Koziolek M, Schwarz A, Benohr P, Middel P, Schwarz G, et al. Proinflammatory role of fractalkine (CX3CL1) in rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Rheumatology. 2003;30(9):1918–1927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Nanki T, Urasaki Y, Imai T, Nishimura M, Muramoto K, Kubota T, et al. Inhibition of fractalkine ameliorates murine collagen-induced arthritis. Journal of Immunology. 2004;173(11):7010–7016. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.7010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Volin MV, Woods JM, Amin MA, Connors MA, Harlow LA, Koch AE. Fractalkine: a novel angiogenic chemokine in rheumatoid arthritis. American journal of Pathology. 2001;159(4):1521–1530. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62537-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Combadiere C, Potteaux S, Gao JL, Esposito B, Casanova S, Lee EJ, et al. Decreased atherosclerotic lesion formation in CX3CR1/apolipoprotein E double knockout mice. Circulation. 2003;107(7):1009–1016. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000057548.68243.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Eriksson EE. Mechanisms of leukocyte recruitment to atherosclerotic lesions: Future prospects. Current Opinion in Lipidology. 2004;15(5):553–558. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200410000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Umehara H, Goda S, Imai T, Nagano Y, Minami Y, Tanaka Y, et al. Fractalkine, a CX3C-chemokine, functions predominantly as an adhesion molecule in monocytic cell line THP-1. Immunology and Cell Biology. 2001;79(3):298–302. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2001.01004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Lee SJ, Namkoong S, Kim YM, Kim CK, Lee H, Ha KS, et al. Fractalkine stimulates angiogenesis by activating the Raf-1/MEK/ERK- and PI3K/Akt/eNOS-dependent signal pathways. American Journal of Physiology, Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2006;291(6):H2836–H2846. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00113.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Singh RK, Fidler IJ. Regulation of tumor angiogenesis by organ-specific cytokines. In: Gunthert U, Birchmeier W, editors. Attempts to understand metastasis formation II. New York: Springer; 1996. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Folkman J. Angiogenesis in cancer, vascular, rheumatoid and other disease. Nature Medicine. 1995;1(1):27–31. doi: 10.1038/nm0195-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Keane MP, Arenberg DA, Lynch JP, III, Whyte RI, Iannettoni MD, Burdick MD, et al. The CXC chemokines, IL-8 and IP-10, regulate angiogenic activity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Journal of Immunology. 1997;159(3):1437–1443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Arenberg DA, Polverini PJ, Kunkel SL, Shanafelt A, Hesselgesser J, Horuk R, et al. The role of CXC chemokines in the regulation of angiogenesis in non- small cell lung cancer. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 1997;62(5):554–562. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.5.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Fidler IJ. Cancer biology: Invasion and metastasis. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Fidler IJ, Ellis LM. The implications of angiogenesis for the biology and therapy of cancer metastasis. Cell. 1994;79:185–188. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Nicolson GL. Tumor and host molecules important in the organ preference of metastasis. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 1991;2(3):143–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Fidler IJ, Singh RK, Yoneda J, Kumar R, Xu L, Dong Z, et al. Critical determinants of neoplastic angiogenesis. Cancer Journal from Scientific American. 2000;6(Suppl 3):S225–S236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Balkwill F. Chemokine biology in cancer. Seminars in Immunology. 2003;15(1):49–55. doi: 10.1016/s1044-5323(02)00127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Muller A, Homey B, Soto H, Ge N, Catron D, Buchanan ME, et al. Involvement of chemokine receptors in breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2001;410(6824):50–56. doi: 10.1038/35065016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Murphy PM. Chemokines and the molecular basis of cancer metastasis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345(11):833–835. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200109133451113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Fidler IJ. The organ microenvironment and cancer metastasis. Differentiation. 2002;70(9–10):498–505. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2002.700904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Nakamura ES, Koizumi K, Kobayashi M, Saitoh Y, Arita Y, Nakayama T, et al. RANKL-induced CCL22/macrophage-derived chemokine produced from osteoclasts potentially promotes the bone metastasis of lung cancer expressing its receptor CCR4. Clinical and Experimental Metastasis. 2006;23(1):9–18. doi: 10.1007/s10585-006-9006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Balkwill F. Cancer and the chemokine network. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2004;4(7):540–550. doi: 10.1038/nrc1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Cabioglu N, Yazici MS, Arun B, Broglio KR, Hortobagyi GN, Price JE, et al. CCR7 and CXCR4 as novel biomarkers predicting axillary lymph node metastasis in T1 breast cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2005;11(16):5686–5693. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Hao L, Zhang C, Qiu Y, Wang L, Luo Y, Jin M, et al. Recombination of CXCR4, VEGF, and MMP-9 predicting lymph node metastasis in human breast cancer. Cancer Letters. 2007;253:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Smith MC, Luker KE, Garbow JR, Prior JL, Jackson E, Piwnica-Worms D, et al. CXCR4 regulates growth of both primary and metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Research. 2004;64(23):8604–4612. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Allinen M, Beroukhim R, Cai L, Brennan C, Lahti-Domenici J, Huang H, et al. Molecular characterization of the tumor microenvironment in breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2004;6(1):17–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Saur D, Seidler B, Schneider G, Algul H, Beck R, Senekowitsch-Schmidtke R, et al. CXCR4 expression increases liver and lung metastasis in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(4):1237–1250. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Wehler T, Wolfert F, Schimanski CC, Gockel I, Herr W, Biesterfeld S, et al. Strong expression of chemokine receptor CXCR4 by pancreatic cancer correlates with advanced disease. Oncology Reports. 2006;16(6):1159–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Scotton CJ, Wilson JL, Scott K, Stamp G, Wilbanks GD, Fricker S, et al. Multiple actions of the chemokine CXCL12 on epithelial tumor cells in human ovarian cancer. Cancer Research. 2002;62(20):5930–5938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Burger M, Glodek A, Hartmann T, Schmitt-Graff A, Silberstein LE, Fujii N, et al. Functional expression of CXCR4 (CD184) on small-cell lung cancer cells mediates migration, integrin activation, and adhesion to stromal cells. Oncogene. 2003;22(50):8093–8101. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Pan J, Mestas J, Burdick MD, Phillips RJ, Thomas GV, Reckamp K, et al. Stromal derived factor-1 (SDF-1/CXCL12) and CXCR4 in renal cell carcinoma metastasis. Molecular Cancer. 2006;5:56. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Kaifi JT, Yekebas EF, Schurr P, Obonyo D, Wachowiak R, Busch P, et al. Tumor-cell homing to lymph nodes and bone marrow and CXCR4 expression in esophageal cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2005;97(24):1840–1847. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Scala S, Ottaiano A, Ascierto PA, Cavalli M, Simeone E, Giuliano P, et al. Expression of CXCR4 predicts poor prognosis in patients with malignant melanoma. Clinical Cancer Research. 2005;11(5):1835–1841. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Arya M, Patel HR, McGurk C, Tatoud R, Klocker H, Masters J, et al. The importance of the CXCL12-CXCR4 chemokine ligand-receptor interaction in prostate cancer metastasis. Journal of Experimental Therapeutics and Oncology. 2004;4(4):291–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Schimanski CC, Schwald S, Simiantonaki N, Jayasinghe C, Gonner U, Wilsberg V, et al. Effect of chemokine receptors CXCR4 and CCR7 on the metastatic behavior of human colorectal cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2005;11(5):1743–1750. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Su L, Zhang J, Xu H, Wang Y, Chu Y, Liu R, et al. Differential expression of CXCR4 is associated with the metastatic potential of human non-small cell lung cancer cells. Clinical Cancer Research. 2005;11(23):8273–8280. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Hu J, Deng X, Bian X, Li G, Tong Y, Li Y, et al. The expression of functional chemokine receptor CXCR4 is associated with the metastatic potential of human nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research. 2005;11(13):4658–4665. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Laverdiere C, Hoang BH, Yang R, Sowers R, Qin J, Meyers PA, et al. Messenger RNA expression levels of CXCR4 correlate with metastatic behavior and outcome in patients with osteosarcoma. Clinical Cancer Research. 2005;11(7):2561–2567. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Kim J, Takeuchi H, Lam ST, Turner RR, Wang HJ, Kuo C, et al. Chemokine receptor CXCR4 expression in colorectal cancer patients increases the risk for recurrence and for poor survival. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(12):2744–2753. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Airoldi I, Raffaghello L, Piovan E, Cocco C, Carlini B, Amadori A, et al. CXCL12 does not attract CXCR4 + human metastatic neuroblastoma cells: clinical implications. Clinical Cancer Research. 2006;12(1):77–82. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]