Abstract

Recent studies have significantly improved our understanding of the role microRNAs (miRNAs) play in regulating normal hematopoiesis. miRNAs are critical for maintaining hematopoietic stem cell function and the development of mature progeny. Thus, perhaps it is not surprising that miRNAs serve as oncogenes and tumor suppressors in hematologic malignancies arising from hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, such as the myeloid disorders. A number of studies have extensively documented the widespread dysregulation of miRNA expression in human acute myeloid leukemia (AML), inspiring numerous explorations of the functional role of miRNAs in myeloid leukemogenesis. While these investigations have confirmed that a large number of miRNAs exhibit altered expression in AML, only a small fraction has been confirmed as functional mediators of AML development or maintenance. Herein, we summarize the miRNAs for which strong experimental evidence supports their functional roles in AML pathogenesis. We also discuss the implications of these studies on the development of miRNA-directed therapies in AML.

Keywords: microRNAs, leukemia, hematopoiesis, hematologic malignancies, leukemogensis

INTRODUCTION

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) exhibit the unique ability to undergo self-renewal and to give rise to all cells of the hematopoietic system throughout the lifetime of an organism (Weissman, 2000; Kondo et al., 2003). In order for HSCs to maintain hematopoiesis, the balance between self-renewal and differentiation is finely regulated under both steady-state and stress conditions. Several molecular networks that control these processes have been identified in recent years (Ramalho-Santos et al., 2002; Park et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2006; Miyamoto et al., 2007; Deneault et al., 2009; Hope et al., 2010; Aguilo et al., 2011; Ting et al., 2012). As a part of this effort, microRNAs (miRNAs) have been identified as regulators of HSC maintenance and lineage commitment (Kluiver et al., 2007; Vasilatou et al., 2010). For example, miR-223 regulates granulopoiesis (Fazi et al., 2005), miR-221 and miR-222 negatively control erythropoiesis (Felli et al., 2005), and miR-146, miR-150, and miR-181 promote B-lymphocyte development (Chen et al., 2004; Zhou et al., 2007; Cameron et al., 2008).

Given the role of miRNAs in regulating normal hematopoiesis, it is perhaps not surprising that miRNA misexpression may contribute to the development of hematopoietic malignancies such as acute myeloid leukemia (AML). AML consists of a heterogeneous group of malignancies characterized by the accumulation of immature blasts and limited production of normal blood cell components in the bone marrow (BM). While better supportive care practices have mildly improved the prognosis of AML in the past two decades, approaches to treat AML have remained essentially unchanged. Thus, understanding the molecular mechanisms regulating the pathogenesis of AML is of great interest.

The importance of miRNAs in carcinogenesis has been inferred by their localization to genomic regions that are frequently deleted or amplified, and to their presence near translocation breakpoints, in various human cancers (Calin et al., 2004). The relevance of miRNAs to hematologic malignancies was first established when miR-15 and miR-16 were shown to be the critical genetic elements deleted from chromosome 13q14 in a significant proportion of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients. In the context of AML, gene expression profiling of AML patient blasts revealed a widespread deregulation of miRNAs. These studies also established associations between different miRNA signatures and specific molecular subtypes of disease, suggesting their potential role in AML pathogenesis (Dixon-McIver et al., 2008; Garzon et al., 2008a; Jongen-Lavrencic et al., 2008). The results of these studies can be found in a number of previously published reviews (Kluiver et al., 2006; Havelange et al., 2009; Vasilatou et al., 2010; Chung et al., 2011).

While these gene expression analyses have been used to document the transcriptional dysregulation of miRNAs in AML and to identify potential diagnostic and prognostic miRNAs, they have provided limited definitive evidence regarding the roles of miRNAs in AML pathogenesis. In fact, few miRNAs have been experimentally validated as mediators of initiation and/or maintenance of AML. In this review, we will focus our discussion on miRNAs for which a functional link between miRNA dysregulation and the development of AML has been established, including miRNAs-125, -146, -155, -142, and -29.

miR-125

miR-125 is among one of the most extensively studied miRNAs in the hematopoietic system. Members of the miR-125 family are located in three highly conserved miRNA clusters throughout the human genome. These clusters include miR-125a/miR-99b/let-7e, miR-125b-2/miR-99a/let-7c-1, and miR-125b-1/miR-100/let-7a-2 located on human chromosomes 19, 21, and 11, respectively. The miR-125 family is highly conserved across species, with the same clusters identified on chromosomes 17, 16, and 9 in the mouse genome.

miR-125 IN HSC SELF-RENEWAL AND SURVIVAL

A number of groups have observed high expression of miR-125 family members in HSCs and decreased expression during myeloid differentiation, suggesting that miR-125 positively regulates HSC function (O’Connell et al., 2010; Ooi et al., 2010; Gerrits et al., 2012). O’Connell et al. (2010) ectopically expressed miR-125b in human CD34+ cells and showed that this leads to a significant increase in the number of CD45+ cells and to the expansion of human stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) in the bone marrow of xenotransplanted mice (O’Connell et al., 2010). Similarly, Ooi et al. (2010) ectopically expressed miR-125b at levels 35-fold higher than endogenous levels via lentiviral transduction in mouse HSCs. Upon transplantation of these transduced HSCs, recipient mice displayed increased numbers of HSCs, but not of other immature hematopoietic cells, in both primary and secondary recipients. miR-125b overexpression was also shown to reduce the levels of apoptosis in HSCs, a process likely mediated through miR-125b inhibition of the pro-apoptotic genes Klf13 and Bmf. Thus, these findings suggest that miR-125b promotes HSC self-renewal by promoting HSC survival (Ooi et al., 2010). Consistent with this prediction, overexpression of miR-125b by 100-1000 fold in HSC-enriched bone marrow significantly improved engraftment in lethally irradiated recipients (Gerrits et al., 2012). Similarly, Guo et al. (2010) described an 8-fold increase in HSC number following enforced expression of miR-125a. Lastly, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)-treated BM cells overexpressing miR-125a displayed increased HSC function as measured by day-35 cobblestone-area forming cell (CAFC) activity and long-term transplantation assays (Gerrits et al., 2012). Therefore, both miR-125a and miR-125b appear to be potent mediators of HSC self-renewal.

miR-125 IN HEMATOPOIESIS AND LEUKEMIA

miR-125b can act as a tumor suppressor or an oncogene depending upon tumor type. In breast cancer, miR-125b appears to act as a tumor suppressor, as high levels of miR-125b inhibit the expression of the proto-oncogenic proteins ERBB2 and ERBB3 (Sonoki et al., 2005; Bousquet et al., 2008). In contrast, in prostate cancer, miR-125b exhibits pro-oncogenic activity, with high miR-125b expression inducing androgen-independent growth through the negative regulation of Bak1, a pro-apoptotic Bcl2 family member (Shi et al., 2007). In AML, miR-125b is strongly up-regulated in patient blasts, and both in vivo and in vitro models suggest that miR-125b can promote the transformation of normal hematopoietic cells into malignant cells.

Insight into the biological effects of miR-125b comes from both in vitro and in vivo ectopic expression studies. miR-125b overexpression blocks terminal (monocytic and granulocytic) differentiation in HL60 and NB4 AML cell lines (Bousquet et al., 2008; Klusmann et al., 2010) and confers interleukin-3 (IL-3) growth independence to the leukemic cell line, 32Dclone3 (Bousquet et al., 2012). ABTB1 and CBFB have been identified as miR-125b targets that may mediate these anti-apoptotic and pro-proliferative effects (Lin et al., 2011; Bousquet et al., 2012). In vivo, primary recipients of HSCs overexpressing miR-125b (35-fold) display myeloid-biased differentiation and expansion at the expense of B cells, while secondary recipients develop a lymphoproliferative disease. This increase in lymphocyte output is likely due to the preferential expansion of lymphoid-biased Slam- HSCs, as they display intrinsically higher basal apoptotic rates, which makes them more prone to miR-125’s anti-apoptotic effects. Furthermore, a 35-fold overexpression of miR-125b was also associated with an expansion of common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs; Ooi et al., 2010). Consistent with these studies, enforced expression of miR-125a in BM cells by 1000-fold enhanced long-term reconstitution of all blood lineages following transplantation. This effect persisted in secondary transplants, although it was also associated with increased myeloid cell output (Guo et al., 2010; Gerrits et al., 2012). The majority of these mice also exhibited a myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN)-like phenotype that occasionally progressed to AML beginning ∼5 months post-transplant. The AML phenotype persisted upon serial transplantation (Gerrits et al., 2012). In a separate study, however, engraftment of HSCs ectopically expressing miR-125a declined over time in secondary recipients (Gerrits et al., 2012), suggesting that miR-125a cannot maintain long-term HSC self-renewal.

The pro-apoptotic gene, Bak1, was shown to be a bona fide target of miR-125a since its co-expression with miR-125a in 5-FU-treated BM blocked hematopoietic expansion in vitro. However, Bak1-null mice displayed a different hematopoietic phenotype, suggesting that miR-125a targets multiple genes to produce the myeloproliferative phenotype (Lindsten et al., 2000, 2003). In another study, Lin28a, a known target of miR-125, was suggested to partially mediate miR-125’s effects on lineage commitment since knocking down Lin28a in bone marrow cells increased myeloid cell number and reduced the number of B cells in mice, a phenotype reminiscent of the effects of miR-125b overexpression. However, leukemia did not develop in mice transplanted with Lin28a knockdown HSCs, suggesting that Lin28a is necessary, but not sufficient, for miR-125-driven leukemogenesis (Chaudhuri et al., 2012).

The miR-125 overexpression studies have revealed numerous phenotypes including lineage bias, enhanced HSC function, and the induction of leukemia, raising questions regarding the physiologic role of miR-125. It appears that the varying phenotypes are likely due to differences in miR-125 expression levels. Mice transplanted with human fetal liver (FL) cells expressing miR-125b at ∼1500-fold higher than endogenous levels develop a MPN-like disorder, while slightly lower levels of miR-125b expression (500-1000 fold) induce B- or T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemias (B-ALL, T-ALL; Bousquet et al., 2010). Similarly, mice transplanted with 5-FU-treated BM cells expressing approximately 100-fold higher levels of miR-125b-1 and miR-125b-2 display expansion of all leukocyte lineages including lymphocytes, while mice expressing miR-125b at significantly higher levels (500-1000 fold) develop a MPN-like disorder. Although other experimental factors, such as starting HSPC populations and methods of handling of HSCs in vitro during viral transduction were not completely identical in these studies, the data suggest a strong gene dose:phenotype correlation.

Consistent with miR-125b’s leukemogenic function, co-transducing 5-FU-treated BM cells with miR-125b (overexpressed 500-fold) and the BCR-ABL fusion gene or mutant C/EBPα accelerated the development of leukemia (B-ALL, MPN, or mixed leukemia with BCR-ABL, and myeloid leukemia with C/EBPα; Bousquet et al., 2010; Enomoto et al., 2012). Furthermore, a number of studies have implicated miR-125b in the development of acute megakaryocytic leukemia (AMKL), particularly in patients with Down’s syndrome (DS). DS is characterized by trisomy 21; miR-125b-2 is located on chromosome 21, and is expressed at markedly higher levels in patients with AMKL (both DS and non-DS related). Consistent with its role in determining the differentiation characteristics of AMKL, ectopic expression of miR-125b in K562 cells promotes megakaryocytic differentiation, and enforced expression of miR-125b in megakaryocytic progenitors (MPs) and megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors (MEPs) isolated from mouse E12.5 FL leads to increases in the size, frequency, and re-plating capacity of megakaryocyte colony-forming units (Klusmann et al., 2010).

To better understand the mechanism by which miR-125 promotes megakaryocytic differentiation, investigators have studied two miR-125b target genes, DICER1 and the tumor suppressor ST18, both characterized as negative regulators of megakaryopoiesis. Knocking down DICER1 or ST18 in FL cells leads to megakaryocytic expansion, reminiscent of the phenotype observed upon miR-125b overexpression. However, the expansion was milder when compared to the miR-125b-driven phenotype, suggesting that other miR-125b targets are likely involved in this process. These studies also suggest that miR-125b aberrantly induces self-renewal in fetal committed MPs and MEPs, as miR-125b-2 overexpression in these cells causes them to continue to proliferate in the presence of limited growth factors (e.g., TPO alone) in liquid culture for >1 month. Similar results were obtained using CD34+ cells from human cord blood (Klusmann et al., 2010), but not adult bone marrow MEPs, suggesting that miR-125 plays distinct roles in adult and fetal hematopoiesis. These results provide a potential molecular basis for the robust association between DS and the development of AMKL, and likely explains the higher incidence of AMKL in pediatric populations relative to adults (Hasle, 2001).

In summary, the miR-125 family regulates self-renewal, both in HSCs as well as fetal MP and MEPs. The variance in hematopoietic phenotypes induced by miR-125 overexpression can be attributed, in large part, to the level of overexpression, with lower levels of miR-125 expression regulating hematopoietic differentiation and proliferation and leading to myeloid (and sometimes T-cell) expansion at the expense of B cells, while the highest levels induce the development of a MPN-like phenotype that progresses to AML (Table 1). The relevance of these studies to human disease is worth considering, as miR-125 is upregulated by no more than 90-fold in myeloid malignancies (Bousquet et al., 2008). Therefore, the high levels of miR-125 expression in these studies raise concerns for possible non-physiologic and/or off-target effects that may not entirely reflect miR-125’s normal biological contribution to these processes. These concerns could be addressed by developing miR-125 seed sequence mutants or through overexpression at levels similar to that observed in patient samples. In addition, complementary studies using additional knockdown approaches [e.g., locked nucleic acids (LNA’s) and sponges], and miR-125-targeted deletions could be used to determine whether miR-125 is required for the development of leukemia in mouse models and if it regulates the function of leukemic stem cells or HSCs (Elmen et al., 2005; Ebert and Sharp, 2010; Chu et al., 2012). Unfortunately, the presence of multiple miR-125 family members and their potentially overlapping and/or redundant functions make the generation of a miR-125-null mouse technically challenging. Finally, while the two miR-125 paralogs share the same seed sequence, they differ in their mature sequence; thus, understanding the target genes mediating the specific effects of miR-125a and miR-125b will be an important area of investigation in the future.

Table 1.

Summary of studies on miR-125 in hematopoiesis and leukemia.

| miRNA | Study | Cell type | 1° transplant |

2° transplant |

Potential targets | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timepoint analyzed | Hematopoietic phenotype | Timepoint analyzed | Hematopoietic phenotype | ||||

| miR-125b | Ooi et al. (2010), PNAS | HSC | 2.5 months | 35X expression: • Increased hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) number • Reduced HSC apoptosis • GM expansion • Reduced B cells |

2.5 months | • GM expansion • Increased B cells • Lymphoproliferative disease with low penetrance |

Pro-apoptotic Klf13 and Bmf |

| miR-125b-1, miR-125b-2 | O’Connell et al. (2010), PNAS | 5-FU-treated BM cells | 2 months | 100X expression: • Expansion of all WBCs including myeloid cells and lymphocytes 500–1000X expression: • Myeloproliferative disease (MPD), as evidenced by granulocyte/monocyte (GM) expansion • Reduced B cells, • Reduced platelets and RBCs, • Splenomegaly • Myeloid cell infiltration in the liver |

• Not investigated | ||

| miR-125b | Bousquet et al. (2008, 2010), JEM, PNAS | Fetal liver (FL) cells | 4 months | 500X expression: • T-ALL 1000X expression: • B-ALL 1500X expression: • Myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) |

• Not investigated | ABTB1, CBFB | |

| miR-125a | Guo et al. (2010), PNAS | 5 × 105 Total BM | 4 months | 1000X expression: • Enhanced reconstitution • >8-fold HSC expansion using limiting dilution analysis • The number of myeloid cells predominated with a reduced proportion of lymphoid cells |

5 months | • Enhanced reconstitution | Pro-apoptotic Bak1 |

| miR-125a | Gerrits et al. (2012), Blood | 5–10 × 106 5-FU-treated BM cells |

2.5–5 months | 1500X expression: • Increased stem cell number • The number of GM and T-cells predominated with a reduced proportion of B lymphoid cells |

1.5–6 months | • Unlike Guo et al. (2010), reduced engraftment of HSCs | |

miR-146

miR-146a is located on chromosomes 5 and 11 in the human and mouse genomes, respectively. Mature miR-146a is differentially expressed during hematopoietic development, with relatively low expression levels in HSPCs, and higher levels upon differentiation, especially in activated macrophages and T-cells (Boldin et al., 2011; Starczynowski et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2012), pointing to a potential role in hematopoiesis. However, miR-146a is expressed ∼1.5-fold higher in HSCs and in myeloid progenitors compared to other progenitor subtypes (Zhao and Starczynowski, 2014). miR-146a expression is regulated by several lineage-dependent transcription factors including the myeloid-specific transcription factor, PU.1 (Jurkin et al., 2010; Ghani et al., 2011), and the megakaryocyte-specific transcription factor, PLZF (Labbaye et al., 2008). In this section, we will focus on the role of miR-146a in the innate immune system, myelopoiesis and the development of myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and AML.

miR-146 AND INNATE IMMUNITY

miR-146a has been shown to both regulate, and be regulated by, the NF-kB pathway, a critical mediator of inflammatory signaling, cell survival, differentiation, and proliferation (Silverman and Maniatis, 2001; Taganov et al., 2006; Hayden and Ghosh, 2008; Figure 1). NF-kB positively regulates miR-146a expression by binding two consensus-binding sites in the miR-146a promoter (Taganov et al., 2006). In contrast, miR-146a negatively regulates the NF-kB pathway by targeting of two positive regulators of NF-kB, tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) and IL-1 receptor-associated kinase-1 (IRAK1; Taganov et al., 2007; Figure 1). Consistent with miR-146a’s negative regulation of NF-kB signaling, miR-146a knockout mice display hypersensitivity in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) challenge, as evidenced by significantly elevated pro-inflammatory cytokine production (Boldin et al., 2011). Thus, miR-146a is an important negative regulator of innate immune activation.

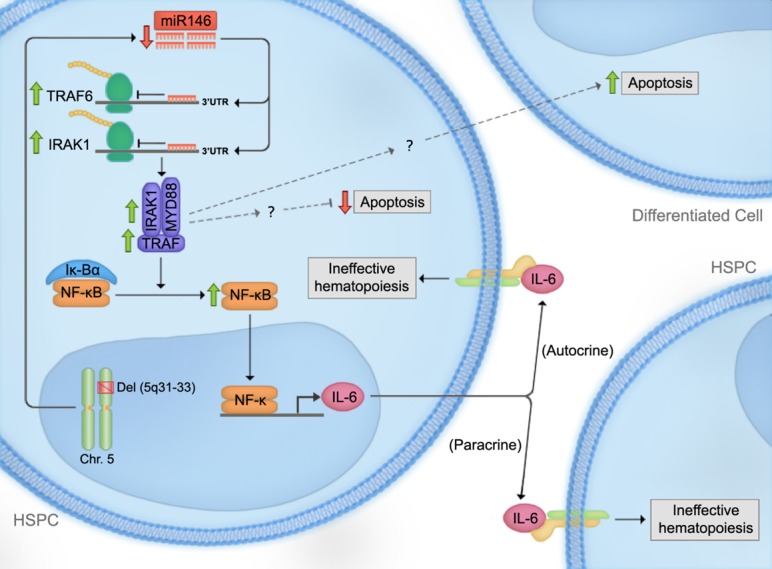

FIGURE 1.

Proposed model for the effect of miR-146a deficiency in the pathogenesis of del(5q) myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS). Loss of one copy of miR-146a results in a decrease in its inhibitory effect on tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6). TRAF6-mediated increase in IL-6 expression leads to autocrine and paracrine effects on HSPCs. Moreover, while TRAF6 exerts autocrine anti-apoptotic roles in HSPCs, it leads to increased apoptosis in a paracrine manner. Thus, these observations could provide a possible mechanism for the observed bone marrow hypercellularity in MDS bone marrows, despite the presence of increased overall apoptosis. Downstream mediators of TRAF6 leading to these effects are currently under investigation.

miR-146a AND NORMAL HEMATOPOIESIS

In normal hematopoiesis, miR-146a is a negative regulator of megakaryopoiesis and granulocyte/macrophage differentiation. Labbaye et al. (2008) showed that miR-146a is downregulated during megakaryopoiesis and that this downregulation is important for normal megakaryopoiesis. Overexpressing miR-146a in human CD34+ cells impaired megakaryocytic proliferation, differentiation, and maturation in vitro, while knocking down miR-146 reversed this phenotype. These phenotypes appear to be mediated by at least two mechanisms: (i) circumventing the negative regulation of miR-146a by PLZF, a megakaryocytic lineage promoting transcriptional repressor, that binds to the miR-146a promoter (Labbaye et al., 2002), and (ii) directly inhibiting CXCR4, which is indispensible for megakaryopoiesis and contains a 3′UTR miR-146a binding site (Avecilla et al., 2004). Together, these studies suggest that megakaryopoiesis is controlled by the PLZF suppression of miR-146a, which in turn relieves the inhibition of CXCR4 by miR-146a. In support of this model, Starczynowski et al. (2010) showed that knocking down miR-146 using a miRNA decoy system in mouse HSPCs increased megakaryopoiesis in vivo through a TRAF6-dependent pathway, and that overexpressing TRAF6 in mouse bone marrow cells resulted in a similar phenotype (Figure 1).

Despite these data supporting a negative role for miR-146a in megakaryopoiesis, other studies have generated contradictory results. For instance, Opalinska et al. (2010) showed that overexpressing miR-146a in mouse HSCs fails to alter megakaryocyte development or platelet production in vivo and in vitro; these findings were confirmed in a separate study by Starczynowski et al. (2011). These conflicting results may stem from the attenuation of miRNA inhibition in the presence of abundant target transcripts, which has been previously described in other contexts (Arvey et al., 2010). As such, miR-146a expression may be sufficiently high in HSCs for maximal target gene inhibition; thus ectopic expression of miR-146a would not be expected to induce a substantial phenotypic change, while knocking down miR-146a would still be expected to release its inhibition of TRAF6 and increase megakaryopoiesis, consistent with early findings of Starczynowski et al. (2010). Alternatively, the effect of miR-146a may be context-specific, since miR-146a overexpression in human HSPCs, specifically, has been shown to impair megakaryocytic differentiation (Labbaye et al., 2008). Bioinformatic approaches assigning miR-146a “inhibition indices” to its key target gene(s) (e.g., TRAF6) in human and mouse HSPCs might help resolve these paradoxical results (Arvey et al., 2010).

While miR-146a seems to a play a role in normal megakaryopoiesis, it also appears to be a negative regulator of granulocyte/macrophage differentiation in the context of aging. miR-146a-null mice display no detectable hematopoietic phenotypes under normal conditions during the first 2 months of life. While the absence of such a phenotype might be explained, in part, by compensatory effects of other members of the miR-146 family, it might also be explained by a model in which miR-146a exerts its effects under non-homeostatic and/or stress conditions. Consistent with the latter, miR-146a-null mice produce increased numbers of granulocyte/monocyte (GM) cells with advancing age (Boldin et al., 2011). Such GM expansions have also been detected in young miR-146a-null mice upon repeated exposure to LPS (Zhao et al., 2013), suggesting that chronic inflammation may contribute to the myeloproliferative phenotype observed in aging miR-146-null mice. Furthermore, overexpressing miR-146a in young HSPCs results in opposite effects on granulopoiesis in young mice, suggesting that miR-146a functions as a transient positive regulator of myelopoiesis in young mice (Opalinska et al., 2010; Starczynowski et al., 2011). Consistent with this, transplantation of miR-146a knockdown HSPCs into lethally irradiated mice results in mild neutropenia (Starczynowski et al., 2010).

In addition to its regulation of myelopoiesis, miR-146a plays a role in HSC maintenance. miR-146a-null mice harbor decreased numbers of CD150+CD48- LT-HSCs by 8 months of age and HSC exhaustion by 12 months. In addition, a functional decline in HSCs is apparent as early as 2 months of age in competitive repopulation assays. These effects are predominantly cell-intrinsic since transplanting WT HSCs into miR-146a-null and normal donors results in minor differences. Intriguingly, miR-146a-deficient lymphocytes display a hyper-activated phenotype with dysregulated cytokine production, suggesting a lymphocyte-mediated mechanism for the reduction of HSC numbers. To test this possibility, miR-146a and Rag1, a gene required for lymphocyte maturation, were simultaneously deleted, leading to a partial rescue of the HSC exhaustion and the myeloproliferative phenotypes observed in miR-146a-null mice (Zhao et al., 2013). These findings are consistent with the systemic autoimmunity observed in some MDS patients (Nimer, 2008).

miR-146a AND MYELOID MALIGNANCIES

miR-146a is located within the common deleted region (CDR) of del(5q) MDS. This deletion is associated with significantly reduced levels of miR-146a in human bone marrow cells compared to other subtypes of MDS. Similar reductions in expression are also observed with miR-145, which is also present in the 5q CDR (Starczynowski et al., 2010). To elucidate the role of these miRNAs in MDS, Starczynowski et al. (2010) knocked down miR-146a and miR-145 in mouse HSPCs and transplanted them into lethally irradiated mice. Eight weeks following transplantation, recipient mice exhibited thrombocytosis, variable neutropenia, and hypolobated megakaryocytes in the bone marrow—all features observed in human del(5q) MDS patients. Using luciferase reporter assays, TIRAP and TRAF6 were identified as target genes of miR-145 and miR-146a, respectively. In order to determine whether TRAF6 is a mediator of the del(5q) MDS phenotype, TRAF6 was overexpressed in mouse bone marrow cells and transplanted into recipient mice. By 12 weeks, the recipient mice developed neutropenia, thrombocytosis, and increased hypolobated megakaryocytes in the bone marrow, and most progressed to bone marrow failure or AML at ≥5 months post-transplantation. In addition, knocking down miR-146a in TRAF6-null cells failed to increase megakaryocyte colony formation in vitro. Similarities between the TRAF6-induced mouse hematopoietic phenotype and human del(5q) MDS strongly suggest that down-regulation of miR-146a in HSPCs plays a critical role in the development of MDS, largely by inhibiting TRAF6. As TRAF proteins are key intermediaries in the activation of canonical NF-kB signaling pathway (Bradley and Pober, 2001), these data suggest that NF-kB may be downstream of miR-146a and responsible for mediating a significant part of the miR-146a phenotype. Support for this model was provided by experiments in which the NF-kB p50 subunit was knocked down and confirmed to rescue some aspects of the myeloproliferative phenotype of miR-146a-null mice (Zhao et al., 2011). Nevertheless, other signaling pathways, including non-canonical NF-kB pathways, contribute to the miR-146a phenotype as well (Etzrodt et al., 2012). For instance, TRAF6 is known to regulate additional signaling pathways through its E3 ubiquitin ligase domain (Yang et al., 2009). Future studies are needed to identify pathways regulated by this activity of TRAF6 in miR-146a-deficient HSPCs.

The co-occurrence of peripheral blood cytopenias with bone marrow hypercellularity and apoptosis is frequently observed in MDS (Boldin et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2011). To explain this apparent paradox, it has been proposed that the increase in apoptosis is counterbalanced by a simultaneous increase in HSPC proliferation (Lepelley et al., 1996). This possibility was investigated in TRAF6-mutant mice that had progressed to bone marrow failure or AML. Non-TRAF6 transduced regions of the bone marrow exhibited elevated levels of apoptosis relative to transduced regions. This finding raises the possibility that TRAF6 protects HSPCs from cell death in a cell autonomous manner while simultaneously promoting apoptosis in non-TRAF6-expressing cells in a non-autonomous manner (Figure 1). Furthermore, megakaryocyte expansions observed in both the transduced and non-transduced cells in mice transplanted with miR-146a knockdown cells suggest a potential paracrine mechanism inducing thrombocytosis (Figure 1). To investigate this possibility, cytokines and growth factors involved in megakaryopoiesis were measured. Increased circulating IL-6, but not other cytokines, was detected in the serum of miR-146a-chimeric mice (Kishimoto, 2005). Concurrent transduction of dominant-negative TRAF6 into mouse HSPCs reversed the phenotype, indicating that IL-6 induction by miR-146a knockdown is mediated through TRAF6. Interestingly, the leukemogenic activity of TRAF6 was not affected when overexpressed in IL-6-null HSPCs, suggesting that a non-IL-6 dependent mechanism mediates the role of TRAF6 in the development of leukemia.

Additionally, the role of miR-146a as a tumor suppressor in MDS is supported by the development of pancytopenia and myeloproliferation involving the spleen, bone marrow, and secondary lymphoid organs in aging miR-146-null mice. Consistent with its negative regulation of myeloproliferation, miR-146a-null BM derived macrophages (BMDM) exhibit increased rates of proliferation, likely due to elevated levels of M-CSF receptor (CSF1R) expression and M-CSF signaling (Boldin et al., 2011).

In summary, miR-146a regulates HSC maintenance as well as megakaryocytic differentiation. It also regulates GM differentiation in an age-dependent manner. Moreover, miR-146a down-regulation contributes to the development of del(5q) MDS and promotes disease progression to AML through the TRAF6-mediated induction of NF-kB and apoptosis. Additional studies are necessary to elucidate the relative contribution of miR-146a to del(5q) MDS pathogenesis by investigating the potential additive or synergistic effects of miR-146a with other genes located in the 5q deleted region (e.g., ribosomal protein RPS14; Ebert et al., 2008) using both mouse models and primary MDS patient samples.

miR-155

Human miR-155, located on human chromosome 21, resides in a spliced and polyadenylated non-coding RNA transcript called the B-cell integration cluster (BIC; Tam, 2001). BIC is an evolutionarily conserved RNA that was initially shown to cooperate with c-Myc to induce lymphomas in chickens when aberrantly activated by pro-viral integrations at a common retroviral integration site (Tam et al., 1997; Tam and Dahlberg, 2006). More recently, studies suggest that miR-155 may also play a role in mediating leukemogenesis. While the mechanisms underlying the transformative activity of this non-coding RNA were a mystery for some time, it has now become clear that BIC contains the pre-miR-155 sequence and that it mediates its oncogenic functions by giving rise to the mature miR-155 transcript (Lagos-Quintana et al., 2002; van den Berg et al., 2003; Eis et al., 2005; Kluiver et al., 2005). In this section, we will review studies that have established a role for miR-155 in the pathogenesis of myeloid malignancies.

miR-155 IN NORMAL AND MALIGNANT MYELOPOIESIS

During steady state hematopoiesis, miR-155 is expressed at high levels in HSPCs and at low levels in most mature hematopoietic cells; for example, miR-155 is expressed at high levels in erythroblasts relative to maturing erythroid progenitors (Georgantas et al., 2007; Masaki et al., 2007; O’Connell et al., 2008). Moreover, miR-155 expression increases during B- (Tam, 2001; van den Berg et al., 2003; Eis et al., 2005; Tam and Dahlberg, 2006; Masaki et al., 2007; Garzon et al., 2008b) and T-cell activation (Rodriguez et al., 2007), and upon exposure of innate immune cells (e.g. monocytes) to inflammatory stimuli such as LPS (Gorgoni et al., 2002; Hayden and Ghosh, 2008; O’Connell et al., 2009). The latter likely explains miR-155’s role in mediating innate immune responses (Georgantas et al., 2007).

Overexpressing miR-155 in HSCs leads to the expansion of GM cells, extramedullary hematopoiesis, and the development of GM cells with morphologic dysplasia in C57BL/6 mice, compatible with a myeloproliferative-like disorder (Garzon et al., 2008a,b; Jongen-Lavrencic et al., 2008). miR-155 is also expressed at low levels in mature erythroid cells, and overexpression of miR-155 in HSCs is associated with a reduction in Ter119+ erythroid progenitors in the mouse bone marrow. This latter finding is consistent with observations in human CD34+ cells overexpressing miR-155 (Georgantas et al., 2007). miR-155 may concurrently inhibit megakaryopoiesis, as miRNA-155-transduced K562 cells treated with hemin, an inducer of megakaryocytic differentiation, exhibit reduced expression of CD41 (Georgantas et al., 2007). While these studies collectively indicate that miR-155 regulates myeloid lineage commitment, the mechanisms by which miR-155 exerts its effects – whether by negatively regulating apoptosis, promoting commitment to the common myeloid progenitor (CMP) lineage in HSPCs, or by increasing the rate of proliferation among myeloid progenitors or their maturing progeny – remains unresolved and will need to be explored in future studies.

Consistent with ectopic overexpression of miR-155 inducing a myeloproliferative phenotype, several studies have shown the upregulation of miR-155 in the bone marrow of NPM1 and FLT3-ITD-mutant AML patients (Garzon et al., 2008a,b; Jongen-Lavrencic et al., 2008). It is also possible that the miR-155 myeloproliferative phenotype was observed due to the effects of miR-155 overexpression being only assessed in the transplantation setting, which requires lethal irradiation, the induction of strong inflammatory responses, and the up-regulation of miR-155 expression in the bone marrow of recipient mice. Consistent with this idea, altered myeloid phenotypes have not been observed in the bone marrow or peripheral blood of miR-155-null mice (Rodriguez et al., 2007).

MECHANISM OF ACTION OF miR-155

To determine which miR-155 target genes are required to induce the miR-155 overexpression phenotype, O’Connell et al. (2008) overexpressed miR-155 in RAW 264.7 myeloid cells and showed reductions in the transcripts of several genes (Bach1, Sla, Cutl1, Csf1r, Jarid2, Cebpβ, PU.1, Arntl, Hif1α, and Picalm) known to play critical roles in hematopoiesis; subsequent studies have established that miR-155 directly inhibits src homology 2 domain-containing inositol-5-phosphatase (SHIP1) as well as CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein-beta (CEBP-β) to mediate leukemogenesis (Gorgoni et al., 2002; O’Connell et al., 2009). The functional link between SHIP1 and miR-155 was strongly suggested by showing that knocking down SHIP1 or overexpressing miR-155 in HSPCs induces similar myeloproliferative phenotypes characterized by increased numbers of CD11b+ myeloid cells in the bone marrow and spleen, decreased erythropoiesis in the bone marrow, and splenomegaly (O’Connell et al., 2009). In contrast to miR-155, which may require previous irradiation to mediate myeloproliferation, SHIP1-null mice display a myeloproliferative phenotype in the absence of stress/inflammatory stimuli. This is likely due to higher baseline levels of cell-intrinsic inflammation in SHIP1-null mice as they are hyper-responsive to cytokine stimulation in vitro (Helgason et al., 2000) due to the loss of SHIP1’s negative regulation of cytokine signaling (Kalesnikoff et al., 2003; Leung et al., 2009). This functional interaction is of great interest since SHIP1 was previously shown to be a tumor suppressor in AML (Luo et al., 2003).

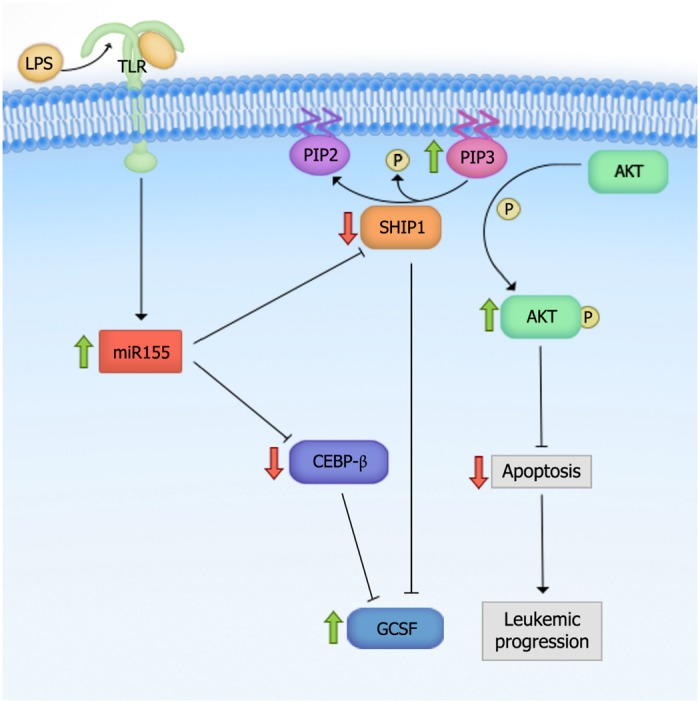

SHIP1 is a phosphatase that mediates the conversion of phosphatidylinositol triphosphate (PIP3) to phosphatidylinositol diphosphate (PIP2). PIP3 normally acts as a docking site for signaling molecules in the PI3K-Akt pathway (e.g., Akt and PLC) and helps relay the signal (Figure 2). Thus, SHIP1 blocks the activation of the PI3K-Akt pathway (Damen et al., 1996; Ono et al., 1996). SHIP1’s ability to suppress the development of AML is probably mediated through this pathway (Luo et al., 2003). Since SHIP1 has been shown to negatively regulate PI3K/Akt signaling, it would be interesting to investigate whether miR-155-induced phenotypes depend on the activation of this pathway. Moreover, in these studies, the phenotypes of SHIP1 and miR-155 were investigated independently. However, the importance of SHIP1 in the miR-155 overexpression phenotype has not been explored by testing the ability of miR-155 to induce phenotypes in the context of SHIP1 loss-of-function or deficiency. It is also unclear at which stage of hematopoietic development the miR-155:SHIP1 interaction is required to induce these phenotypes. It would presumably be in an early progenitor population based on miR-155’s high levels of expression in HSPCs.

FIGURE 2.

Proposed mechanism for miR-155-mediated myeloid leukemogenesis. Overexpression of miR-155 leads to the activation of the PI3K-Akt pathway through negative regulation of Src Homology 2 domain-containing Inositol-5-Phosphatase (SHIP1). SHIP1 is a phosphatase that mediates the conversion of phosphatidylinositol triphosphate (PIP3) to phosphatidylinositol diphosphate (PIP2). PIP3 normally acts as a docking site for signaling molecules in the PI3K-Akt pathway and helps relay the signal. Upon miR-155 overexpression and thus, SHIP1 downregulation, PIP3 level is increased, which leads to the activation of the PI3K-Akt pathway. Green arrows indicate increased, and red arrows decreased activity upon miR-155 overexpression.

Another miR-155 target gene, CEBP-β, appears to ensure that the hyperproliferation under stress is myeloid in nature. CEBP-β is a transcription factor involved in macrophage activation and the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines and acute phase reactants (Gorgoni et al., 2002). In one study, LNA-induced in vivo silencing of miR-155 in the splenocytes of LPS-treated mice led to the de-repression of CEBP-β compared to LNA-control LPS-treated mice. Moreover, antagonism of miR-155 in an AML cell line was also accompanied by a reduction in the inflammatory cytokine G-CSF (Worm et al., 2009). These findings suggest that miR-155 overexpression induces GM expansion by targeting CEBP-β. However, it is unclear whether such a reduction in G-CSF production is dependent on CEBP-β, SHIP1, or both. We speculate that it is likely mediated through SHIP1 since SHIP1-deficient mice have been shown to exhibit increased G-CSF production (Figure 2; Hazen et al., 2009).

Interestingly, miR-155-mediated hematopoietic malignancies exhibit longer latencies compared to more aggressive miRNA leukemia models, such as those induced by miR-125 overexpression. This raises the possibility that additional mutations are required for full transformation. Intriguingly, miR-155 targets mismatch repair genes such as hMLH1, hMSH2, and hMSH6 (Valeri et al., 2010), as well as cell-cycle regulators such as WEE1 (Tili et al., 2011). Thus, miR-155 may increase spontaneous mutation rates in HSPCs, in agreement with observations made in some solid tumor cell lines (Mantovani et al., 2008; Valeri et al., 2010; Tili et al., 2011). It would be interesting to investigate this hypothesis in the context of AML and to determine whehter such mutations are required for the full manifestation of disease phenotypes.

While the cumulative data indicate that miR-155 can initiate early events in myeloid leukemogenesis, it is not clear whether miR-155 is required for leukemic progression or maintenance. Knocking down miR-155 in fully transformed AML cells or reversibly expressing miR-155 in a progressive model of AML would help address these important questions. If miR-155 can be shown to regulate disease maintenance or resistance to therapy, it would be an excellent target in the treatment of AML.

miR-142

miR-142 is located on human chromosome 17. While miR-142 is expressed in all hematopoietic tissues including the bone marrow, spleen and thymus, it is not expressed in non-hematopoietic tissues. Perhaps it is not surprising that the first role ascribed to miR-142 was in promoting the development of the T-cell and myeloid lineages (Chen et al., 2004). miR-142’s importance as a regulator of hematopoiesis was recently underscored by the fact that it is the only miRNA that is recurrently mutated in AML (Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, 2013).

miR-142 IN NORMAL AND MALIGNANT HEMATOPOIESIS

miR-142 regulates normal hematopoiesis as well as the development of lymphoid and myeloid leukemias. By enforcing the expression of miR-142 in Lin- mouse bone marrow cells, Chen et al. (2004) showed that miR-142 increases the absolute numbers of T-cells, leads to a minimal decrease in B-cell differentiation (CD19+), and slightly reduces the number of Mac1+ Gr1- myeloid cells. miR-142 also appears to play a role in the development of mature lymphoid malignancies, as the miR-142 locus is 50bp from the breakpoint of t(8;17), a cytogenetic alteration present in a subset of aggressive mature B-cell leukemias (Gauwerky et al., 1989). This suggests that MYC, located on chromosome 8, is translocated and regulated by the upstream miR-142 promoter (Lagos-Quintana et al., 2002). Interestingly, miR-142-3p is significantly downregulated in ALL patients expressing the MLL-AF4 fusion gene. Ectopic expression of miR-142-3p in MLL-AF4+ cell lines supresses cell proliferation, induces apoptosis, and down-regulates multiple genes known to regulate self-renewal including MLL-AF4, HOXA9, HOXA7, and HOXA10. Thus, miR-142-3p likely functions as a tumor suppressor in MLL-AF4+ ALL (Dou et al., 2013).

In addition to its role in lymphopoiesis and lymphoid malignancies, miR-142 also regulates myeloid differentiation and the development of AML. It is up-regulated during myeloid differentiation in both normal and leukemic HSPCs. Overexpressing miR-142 promotes phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA)-induced monocytic and all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA)-induced granulocytic differentiation in AML cell lines by directly targeting the cyclin T2 (CCNT2) and “TGFβ–activated kinase 1/MAP3K7 binding protein 2” (TAB2) transcripts. In addition, miR-142-3p levels are significantly reduced in CD34+ cells from primary AML samples. This decrease is associated with the increased expression of CCNT2 and TAB2, two predicted miR-142 targets. Conversely, enforced expression of miR-142-3p in HSPCs from healthy controls and AML patients down-regulates the expression of CCNT2 and TAB2 and promotes myeloid differentiation (Wang et al., 2012b). Thus, reductions in miR-142-3p likely result in the differentiation blockade that is characteristic of AML. In support of this model, independent expression profiling studies revealed that miR-142-3p is down-regulated in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from AML patients (Wang et al., 2012a). Furthermore, higher miR-142 expression correlates with a better prognosis in patients with intermediate-risk AML (Wang et al., 2012b; Dahlhaus et al., 2013). Perhaps the most compelling evidence supporting the role of miR-142-3p in leukemogenesis comes from RNA-sequencing studies of AML. Of the samples examined, 7/200 (3.5%) harbored mutations in miRNAs, of which 4/7 (57%) were present in the seed sequence of miR-142-3p. Other non-recurrent mutations identified in miRNAs were found in miR-516b1, miR-1267, miR-891a, and miR-632. Additional studies will be required to elucidate how miR-142 and other mutated miRNAs contribute to AML pathogenesis. This is particularly important because the novel seed sequences generated are predicted to alter target specificity and it is unclear whether these mutations are loss- and/or gain-of-function in nature (Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, 2013).

miR-29

miR-29 family members have been shown to function both as tumor suppressors and oncogenes in myeloid malignancies. The miR-29 family consists of three members, miR-29a, miR-29b, and miR-29c. The miR-29a/miR-29b-1 and miR-29b-2/miR-29c clusters are present on chromosomes 7q32 and 1q23, respectively (Hwang et al., 2007; Garzon et al., 2009a). In this section, we describe the role of miR-29 in regulating epigenetic modifiers, cellular proliferation, apoptosis, and hematopoietic differentiation, and the role of these functional changes in AML pathogenesis.

miR-29 AND EPIGENETIC REGULATION

Myeloid malignancies frequently exhibit epigenetic alterations, and subsets of patients with MDS, MPN, and AML have been shown to harbor activating mutations and loss-of-function mutations in master epigenetic regulators such as DNA methyltransferase 3 (DNMT3) and TET-eleven translocation 2 (TET2); the combination of these mutations account for 33% of the somatic mutations identified in AML (Delhommeau et al., 2009;Langemeijer et al., 2009; Tefferi et al., 2009a,b,c; Patel et al., 2012). Interestingly, the up-regulation of DNMT transcripts (including DNMT1, 3A, and 3B) and reductions in TET2 enzymatic activity have been identified in patients harboring wild-type DNMT and TET2, suggesting that their activity is regulated by transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms (Mizuno et al., 2001; Ko et al., 2010). In a subset of these patients, IDH mutations are likely to account for the dysregulation of TET2 activity, while other unidentified factors also likely alter TET2 activity (Shih et al., 2012).

The down-regulation of miR-29b is thought to promote DNA hypermethylation in AML since miR-29b can directly target DNMT3A, DNMT3B, and Sp1 (a transcriptional regulator of DNMT1; Figure 3A; Garzon et al., 2009b). This link between miR-29 expression and methylation status in AML cells prompted the evaluation of miR-29b as a therapeutic target in AML. Investigators have shown that miR-29b oligonucleotide mimics recapitulate the effects of hypomethylating agents, 5-azacytidine and decitabine, by demethylating the promoters of tumor suppressors estrogen receptor 1 (ESR1) and p15INK4b, and by promoting the re-expression of these genes in AML cell lines (Garzon et al., 2009b). These results indicate that miR-29b oligonucleotides may be an effective therapeutic strategy in the treatment of AML.

FIGURE 3.

miR-29 family members target multiple genes to mediate their biologic effects. (A) miR-29 directly targets DNA methyltransferase 3 (DNMT3a) and DNMT3b, and indirectly targets DNMT1 by down-regulating Sp1, to mediate global DNA hypomethylation in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells. (B) miR-29 targets TET-eleven translocation (TET) family members, TET1, TET2, and TET3, which may or may not mediate global DNA hypermethylation. The down-regulation of TETs induces aberrant self-renewal and the development of myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN’s). (C) miR-29 targets cyclin T2 (CCNT2) and CDK6 to promote myeloid differentiation. (D) miR-29 promotes the down-regulation of c-Kit during normal hematopoiesis. However, the down-regulation of miR-29 in malignant hematopoiesis promotes c-kit-driven AML by up-regulating Sp1, which increases c-Kit expression and suppresses miR-29 expression.

In contrast to DNMTs, which methylate CpG islands and generally mediate transcriptional suppression, TET family members (TET1, TET2, and TET3) demethylate DNA by catalyzing the conversion of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) into intermediates of DNA methylation, including 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), 5-formylcytosine (5fC), and/or 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC; He et al., 2011; Ito et al., 2011). Cheng et al. (2013) found that overexpressing any of the three miR-29 family members in mouse bone marrow cells reduced the level of TET2 as well as its metabolic by-product, 5hmC (Figure 3B). The reduction in 5hmC was rescued by ectopically expressing TET2. Of note, however, reductions in 5hmC levels in the wild-type mice transplanted with miR-29b-transduced bone marrow cells were attributed to global DNA hypermethylation, while direct evaluation of the global DNA methylation (GDM) status of these cells was not performed. Performing mass spectrometry on miR-29 overexpressing cells and evaluating whether the reductions in 5hmC correlate with increases in GDM are critical, as studies identifying reduced 5hmC as a surrogate for global DNA hypomethylation have yielded conflicting results (Ko et al., 2010; Shih et al., 2012). It would also be interesting to evaluate the levels of the DNMTs, TETs, and GDM simultaneously upon miR-29 overexpression in leukemic blasts and normal HSPCs. This would help elucidate whether the effect of miR-29 on DNMTs and TETs are cell context-specific, or whether DNMTs and TETs function to promote the methylation and demethylation of distinct target genes simultaneously.

miR-29 AND MYELOID DIFFERENTIATION

Numerous studies have demonstrated that miR-29 family members are regulators of myeloid differentiation. Han et al. (2010) showed that transplanting mice with HSPCs overexpressing miR-29a results in increased myeloid and reduced lymphoid chimerism 8–12 weeks post-transplant, and is accompanied by splenomegaly as well as megakaryocytic and granulocytic hyperplasia in the bone marrow and spleen, consistent with a myeloproliferative phenotype. Similarly, Wang et al. (2012b) reported that miR-29a expression increases with PMA-induced monocytic differentiation and ATRA-induced granulocytic differentiation in AML cell lines. The latter study showed that the increase in miR-29a expression was associated with reductions in CDK6 levels upon myeloid differentiation and reductions in CCNT2 upon monocytic differentiation. In this study, CCNT2 and CDK6 were shown to be authentic targets of miR-29a, and their reduced expression was necessary and sufficient for enhanced PMA and ATRA-induced myeloid differentiation. These findings were validated in human samples, as miR-29a overexpression partially reversed the differentiation arrest phenotype in primary AML blasts. Moreover, enforced expression of miR-29a in healthy CD34+ cells promoted monocytic and granulocytic differentiation (Wang et al., 2012b). These findings indicate that miR-29a regulates myeloid differentiation, at least partially through the targeting of CCNT2 and CDK6 (Figure 3C). Additional studies have shown that overexpressing another member of the miR-29 family, miR-29b, promoted partial differentiation of an AML cell line, while both miR-29b and miR-29c promoted myeloid differentiation in AML patient CD34+ blasts (Fujimoto et al., 2007; Garzon et al., 2009b; Cheng et al., 2013; Gong et al., 2014). Furthermore, transplanting mouse bone marrow cells overexpressing miR-29b led to biased myeloid differentiation, splenomegaly, and an increased percentage of donor-derived monocytes in the bone marrow, inducing a chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML)-like disease (Cheng et al., 2013). Given these findings, it would be interesting to determine whether miR-29 oligonucleotides can act synergistically with ATRA, arsenic trioxide, or ATRA-arsenic trioxide combinations in primary AML patient blasts to evaluate the potential therapeutic efficacy of miR-29 mimics in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL). Combinatorial regimens including miR-29 with cytarabine and/or daunorubicin could also help elucidate its therapeutic efficacy as a stimulant of myeloid differentiation in non-APL myeloid leukemias.

miR-29 IN CELLULAR PROLIFERATION AND APOPTOSIS

In addition to their roles in epigenetic regulation and differentiation, miR-29a and miR-29b have been shown to regulate a number of cellular processes. A transcriptomal analysis of human leukemia cell lines transfected with synthetic miR-29b revealed the enrichment of genes that regulate apoptosis, cell cycle progression, and cellular proliferation. Altered expression of some of these genes (e.g., MCL-1 and CDK6) was confirmed in primary AML blasts following transfection with miR-29b mimics (Garzon et al., 2009a). These changes were also accompanied by a reduction in phosphorylated Rb (pRb) due to the miR-29 targeting of CDK6 and CCNT2. Similar findings were generated by Gong et al. (2014), who showed that overexpressing miR-29 family members in AML cell lines stimulates apoptosis and inhibits the G1 to S phase cell cycle transition, phenotypes attributed to the miR-29 targeting of CCND2 and AKT2 (Gong et al., 2014; Figure 3D). In contrast, Han et al. (2010) found that overexpressing miR-29a in 293T cells enhanced cell cycle entry without altering apoptosis. In addition, mice overexpressing miR-29a demonstrated a developmental stage-specific increase in proliferation, as multipotent progenitors (MPPs) showed increased numbers of cycling cells while more committed GMP and CMPs did not (Han et al., 2010). These findings suggest that the cellular consequences of miR-29 overexpression are cell-type specific and may depend on the state of differentiation and/or transformation.

miR-29 AS AN ONCOGENE AND TUMOR SUPPRESSOR

While overexpression studies in leukemic cell lines have shown that miR-29 family members are able to regulate leukemic cell growth and survival, other studies have revealed the leukemogenic potential of the miR-29 family. Han et al. (2010) showed that CMPs and GMPs from mice overexpressing miR-29a establish long-term, differentiating grafts in transplantation studies, suggesting that miR-29a overexpression is sufficient to induce aberrant self-renewal in CMPs and GMPs, but not a fully transformed phenotype. Mice serially transplanted with bulk splenocytes or bone marrow cells from these miR-29a overexpressing mice developed organomegaly and increased myeloid blasts in the bone marrow and spleen, consistent with transformation into AML. Similarly, Cheng et al. (2013) showed that mice transplanted with bone marrow cells overexpressing miR-29b developed splenomegaly and an increase in myeloid bias index, which are accompanied by reductions in 5hmC levels. Interestingly, the authors found that expression of TET2 partially rescued this malignant phenotype. It remains unclear whether overexpression of TET1, TET2, and TET3 together could completely rescue the phenotype. All of the TET family members regulate DNA methylation and are bona fide targets of miR-29b, making this a possibility. Nevertheless, these studies indicate that the enforced expression of miR-29a in immature hematopoietic cells drives leukemic transformation, and that this phenotype can be attributed, at least in part, to the targeting of TET2. Moreover, the Han et al. (2010) study emphasizes the need to investigate the function of potential leukemia-modifying genes in a cell-specific manner since the functional consequences can vary dramatically based on cell context. This point is well-illustrated by the finding that miR-29a is up-regulated in patient LSC-enriched fractions and not in non-LSC fractions, which in contrast to other studies that have shown reduced miR-29a levels in whole PBMNC’s and BM CD34+ leukemic blasts (Wang et al., 2012b; Gong et al., 2014). Thus, the down-regulation of miR-29’s observed in previous studies may be due to the inclusion and dominance of non-LSC’s in the evaluated cells.

Consistent with miR-29’s role in promoting leukemogenesis, it appears that inhibiting miR-29 in established blasts may be a promising therapeutic strategy. Injection of precursor miR-29b oligonucleotides in mice engrafted with K562 tumors significantly reduce their size (Garzon et al., 2009a). Subsequent studies showed that a transferrin-conjugated nanoparticle delivery system for synthetic miR-29b (Tf-NP-miR-29b) suppressed AML growth, impaired colony formation, and reduced cell viability in AML patient samples. Tf-NP-miR-29b also reduced spleen weight and increased overall survival in NSG mice transplanted with AML cell lines (Huang et al., 2013). Similarly, intravenous injections of NOD/SCID mice engrafted with AML with viral particles expressing miR-29a, -29b, and -29c reduced the number of CD33+ leukemic cells in the bone marrow and spleen by inhibiting proliferation and stimulating apoptosis (Gong et al., 2014). While the mechanism of leukemic blast clearance was not examined in these studies, others have suggested that the therapeutic effect of miR-29b may be mediated through its regulation of c-Kit through a feedback-loop (Liu et al., 2010). This is not surprising considering that increased c-Kit activation, either through stimulation by its ligand or secondary gain-of-function mutations, has been shown to drive leukemogenesis. In this study, c-Kit was shown to activate the transcription factor, MYC, which subsequently binds to, and inhibits, the miR-29b promoter (Liu et al., 2010). The reduction in miR-29b expression was shown to positively regulate Sp1 levels, thus allowing the formation of the Sp1/NF-kB complex, which binds regulatory sequences to increase c-Kit expression. It was also shown to positively regulate the formation of a complex with HDAC1, which further suppresses miR-29b expression. In support of this model, pharmacologic inhibition of c-Kit with bortezomib in NOD/SCID mice transplanted with c-Kit mutant AML cells (FDC-P1/KITmut) abrogated c-Kit mRNA levels and increased miR-29b expression. In addition, FDC-P1/KITmut cells exhibited reduced tumor size, tumor weight, and engraftment efficiency upon transfection with synthetic miR-29b. These findings demonstrate the therapeutic potential of miR-29 oligonucleotides and suggest that the down-regulation of miR-29b is particularly critical to leukemogenesis in c-Kit-driven AML (Liu et al., 2010).

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Although numerous miRNAs are dysregulated in AML, only a few have been shown to play functional roles in myeloid leukemogenesis (Table 2). Collectively, the data indicate that these miRNAs induce hematopoietic malignancies by exerting their biologic effects in developmental stage-specific manners. A summary of the predicted stage at which each of these miRNAs exerts its leukemogenic function is indicated in Figure 4. It is also worth mentioning that miRNAs may act in non-hematopoietic cell-intrinsic manners to promote leukemogenesis, as demonstrated by Raaijmakers et al. (2010), who showed that deleting the miRNA processing enzyme, DICER1, in mouse osteoprogenitors induces MDS which progresses to AML. These studies suggest that the absence of one or more miRNAs in bone marrow stromal cells may increase the predisposition towards developing myeloid malignancies (Raaijmakers et al., 2010).

Table 2.

Summary of miRNAs with validated functional relevance in the pathogenesis of myeloid malignancies.

| miRNA | Location |

Expression | In vitro phenotype | In vivo phenotype | Bona fide targets | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | Mouse | |||||

| miR-125 | Chr 19, 21, 11 | Chr 17, 16, 9 | • Highly expressed in HSCs • Reduced with differentiation |

• Increases HSC self- renewal, decreases apoptosis, confers aberrant self-renewal in FL megakaryocyte erythroid progenitors (MEPs) and megakaryocytic progenitors (MPs) | • Enhances long-term reconstitution, reduces apoptosis in HSCs and progenitors, increases myeloid output at the expense of B cells. can lead to ALL at high doses as well as MPN/AML at very high doses | Klf13, Bmf, Bak1, Dicer, ST18, ABTB1, CBFB |

| miR-142 | Chr 17 | Chr 11 | • Most highly expressed in lymphoid and myeloid progenitors • Downregulated in AML patient samples |

• Ectopic expression in MLL-AF4+ cell lines suppressed cell proliferation, induced apoptosis, and downregulated multiple genes known to regulate self-renewal • Ectopic expression in in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cell lines increases PMA– and ATRA-induced differentiation |

Not investigated | Cyclin T2, TAB2 |

| miR-146 | Chr 5 | Chr 11 | • Expressed at relatively low levels in stem and progenitors and upregulated upon differentiation • Highly expressed in macrophages and T cells • Low expression in megakaryocytic progenitors (MPs) |

• Overexpression leads to decreased megakaryopoiesis in human CD34+ HSPCs | • miR-146-null mice display hypersensitivity to LPS challenge, increased megakaryopoiesis. They also display pancytopenia and GM expansion with aging • miR-146 KD in murine HSPCs followed by transplantation results in increased megakaryopoiesis, and an MDS phenotype with thrombocytosis and neutropenia |

TRAF6, IRAK1 |

| miR-155 | Chr 21 | Chr 16 | • Relatively higher basal expression in HSPCs compared to more mature populations, such as erythroid progenitors • Induced in innate immune cells upon inflammatory stimuli as well as activated B and T cells |

• Ectopic expression of miR-155 in K562 cells leads to a decreased CD41+ megakaryocytic differentiation | • Enforced expression in HSCs leads to development of a MPN/MPD with abnormal GM morphology, along with a reduction in erythroid progenitors in the bone marrow | SHIP1, Cebpβ |

| miR-29 | Chr 7, 1 | Chr 6, 1 | • Highest levels of expression in HSCs and MPPs, followed by LSCs, CMPs, MEPs, and GMPs; levels decrease with differentiation • Increased in patient LSCs, but not in non-LSCs |

• Ectopic miR-29 expression in AML cell lines leads to global DNA hypomethylation and reduces 5hmC levels; • Positively regulates myeloid differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis |

• Ectopic expression reduces the size of K562-laden tumors, via inhibiting proliferation and stimulating apoptosis and increases OS of mice with AML • Ectopic expression in early hematopoietic cells leads to induction of aberrant GMP self-renewal and the development of MPD with progression to AML |

DNMT3A, DNMT3B, Sp1, TET family, CDK6, CCNT2, AKT2, HBP1 |

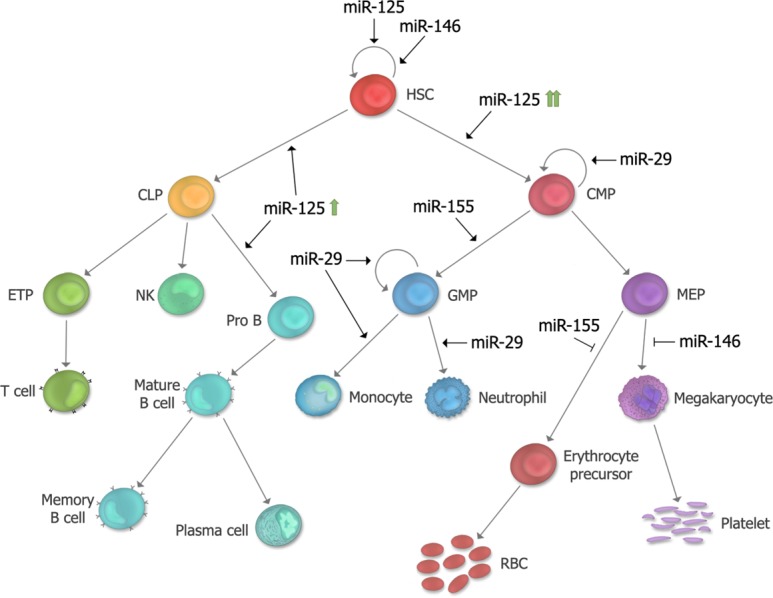

FIGURE 4.

Summary of proposed developmental stages at which microRNAs (miRNAs) functionally contribute in leukemogenesis. The stages at which each of the five miRNAs described in this review exert their effect in hematopoiesis and leukemogensis are depicted. miR-125 is a positive regulator of HSC self-renewal, and depending on its level of expression, can lead to biased myeloid or lymphoid differentiation. miR-146a regulates HSC maintenance as well as megakaryocytic differentiation. miR-155 is a positive regulator of GM differentiation and a negative regulator of erythroid differentiation. miR-29 is a positive regulator of myeloid differentiation, and overexpression can induce aberrant self-renewal of GMP’s. HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; CMP, common myeloid progenitor; MEP, megakaryocyte erythroid progenitor; RBC, red blood cell; GMP, granulocyte macrophage progenitor; CLP, common lymphoid progenitor; ETP, early thymic progenitor; NK, Natural Killer cell.

miRNAs with leukemogenic roles have been identified predominantly through high-throughput gene expression analyses. Despite the high number of miRNAs exhibiting altered expression in AML, sequencing of patient samples has revealed that somatic mutations in miRNAs are relatively rare events in human AML (Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, 2013). Thus, miRNA deregulation in AML patients is largely due to alterations in transcriptional and/or post-transcriptional regulation. Furthermore, miRNAs are normally processed post-transcriptionally in a multi-step process involving DROSHA and DICER, each of which is regulated by several signaling molecules and RNA-binding proteins (Obernosterer et al., 2006; Thomson et al., 2006; Winter et al., 2009; Saj and Lai, 2011). Thus, understanding the complex regulation of the miRNAs that have been implicated in AML may provide novel avenues for therapeutic development. Moreover, many miRNAs are organized in clusters throughout the genome, and are expressed in a concerted manner. Paradoxically, however, individual members of a cluster can function in different or even opposite manners. For example, while miR-125 can serve as an oncogene in the context of breast cancer (Iorio et al., 2005; Scott et al., 2007), its cluster partner, let-7, functions as a tumor suppressor in the same context (Lee and Dutta, 2007). These results suggest that miRNAs residing in clusters undergo different modes of post-transcriptional regulation. Thus, differing modes of post-transcriptional regulation of miRNAs within the same cluster might explain how such miRNAs serve opposing roles.

Although few miRNAs are mutated in human AML, many are known to be located in the proximity of breakpoints in chromosomal translocations/deletions (Calin et al., 2004). These observations suggest that miRNAs may contribute to disease pathogenesis, while the presence of additional genes in the deleted/translocated regions implies a potential cooperativity with miRNAs in leukemogenesis. In line with this idea, it is known that AML is a multi-step process, the understanding of which requires functional analyses of co-occurring disease alleles (Jan et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2014). This raises the possibility that genetic interaction studies between miRNAs and concurrently dysregulated or mutated genes might provide more accurate models to study disease. For instance, miR-146a is located in the del(5q) region observed in some MDS patients along with about 40 other genes, including the ribosomal protein RPS14 (Ebert et al., 2008). While miR-146a studies have provided precious insight into our understanding of MDS biology, they only partially recapitulate features of MDS. Thus, experiments employing approaches that evaluate loss-of-function del(5q) genes in combination with miR-146a loss might provide a more nuanced understanding of MDS pathogenesis.

Identification of target genes through which the pathogenic miRNAs in AML exert their effects is critical to understanding disease biology. A limited number of targets have been validated for each of these miRNAs and thus identification of bona fide target genes remains a major challenge in the field. Whereas some miRNAs mediate their function through a limited number of key target genes, others exert their action through many. To identify target genes mediating the effect of individual miRNAs, advanced target identification methods such as whole proteomics approaches and biochemical analyses of miRNA:mRNA interactions will be required. These techniques include RISC complex pull-down, RIP-Seq, HITS-CLIP and PAR-CLIP, which have been summarized in other reviews (Carroll et al., 2014). Furthermore, selective generation of knockin mouse models with mutations in the miRNA binding sites in the 3′-UTR of potential target genes (Jan et al., 2012) would assist the identification of relevant miRNA targets. Finding such target genes may provide additional promising therapeutic targets that have not yet been described (Garzon et al., 2010).

There are documented examples of the successful delivery of miRNA oligonucleotides to target tissues in vivo including the lung (Trang et al., 2011) and liver (Kota et al., 2009). Given the critical role of miRNAs in leukemogenesis, investigators have evaluated whether they might be effective therapeutic targets in AML. The potential use of miRNAs as therapeutic agents or targets in AML is underscored by their ability to regulate multiple signaling pathways that contribute to leukemogenesis (Li et al., 2007; Croce, 2008).

Two strategies may be employed to modulate miRNA activity: (i) enhancing the function of tumor supressor miRNAs using miRNA mimics, and (ii) inhibiting the function of oncogenic miRNAs by limiting their ability to bind to gene targets using antisense oligos or miRNA sponges (Garzon et al., 2010). For such therapies to find their way into the clinic, efficient and safe delivery of the targeting agents are required. Several groups have developed different delivery systems for miRNA targeting treatments (van Rooij and Kauppinen, 2014), including: (i) non-viral oligonucleotides; (ii) viral constructs overexpressing the miRNA or its antagomir (anti-sense oligo); and (iii) small-molecule delivery systems, where miRNA oligonucleotides are conjugated to small-molecules to ensure more efficient delivery (Ibrahim et al., 2011; Pramanik et al., 2011). Validating the optimal method of delivery will represent a significant challenge for miRNA-directed therapy in the future.

Among the leukemogenic miRNAs discussed in this review, miR-155 and miR-29 have been extensively studied as therapeutic targets in other contexts. Successful delivery of miR-155 oligonucleotides to the bone marrow has been confirmed, with the inhibition of miR-155 using a LNA (Takeshita et al., 2010) antagomir that was shown to alleviate symptoms of graft-versus-host disease (Ranganathan et al., 2012). In addition, systemically administered LNA antagonists against miR-155 in a mouse inflammation model inhibited miR-155’s inflammatory effects in mouse splenocytes (Worm et al., 2009). In the context of AML, miR-29b oligonucleotide mimics appear to be promising therapies based on their effects on AML patient samples in vitro (Garzon et al., 2009b) and in K562-driven tumors in vivo (Garzon et al., 2009a). While miR-29b directed treatments show promise, these studies have not been performed using systemically delivered miRNA mimics. We expect to see such studies in the future aimed at identifying and validating more efficient and specific in vivo delivery systems for the treatment of AML.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Alec W. Stranahan is supported by NIH T32 training grant GM008539. Montreh Tavakkoli is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Medical Research Fellow.

REFERENCES

- Aguilo F., Avagyan S., Labar A., Sevilla A., Lee D. F., Kumar P., et al. (2011). Prdm16 is a physiologic regulator of hematopoietic stem cells. Blood 117 5057–5066 10.1182/blood-2010-08-300145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvey A., Larsson E., Sander C., Leslie C. S., Marks D. S. (2010). Target mRNA abundance dilutes microRNA and siRNA activity. Mol. Syst. Biol. 6:363 10.1038/msb.2010.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avecilla S. T., Hattori K., Heissig B., Tejada R., Liao F., Shido K., et al. (2004). Chemokine-mediated interaction of hematopoietic progenitors with the bone marrow vascular niche is required for thrombopoiesis. Nat. Med. 10 64–71 10.1038/nm973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldin M. P., Taganov K. D., Rao D. S., Yang L., Zhao J. L., Kalwani M., et al. (2011). miR-146a is a significant brake on autoimmunity, myeloproliferation, and cancer in mice. J. Exp. Med. 208 1189–1201 10.1084/jem.20101823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousquet M., Harris M. H., Zhou B., Lodish H. F. (2010). MicroRNA miR-125b causes leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 21558–21563 10.1073/pnas.1016611107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousquet M., Nguyen D., Chen C., Shields L., Lodish H. F. (2012). MicroRNA-125b transforms myeloid cell lines by repressing multiple mRNA. Haematologica 97 1713–1721 10.3324/haematol.2011.061515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousquet M., Quelen C., Rosati R., Mansat-De Mas V., La Starza R., Bastard C., et al. (2008). Myeloid cell differentiation arrest by miR-125b-1 in myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia with the t(2;11)(p21;q23) translocation. J. Exp. Med. 205 2499–2506 10.1084/jem.20080285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley J. R., Pober J. S. (2001). Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factors (TRAFs). Oncogene 20 6482–6491 10.1038/sj.onc.1204788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calin G. A., Sevignani C., Dumitru C. D., Hyslop T., Noch E., Yendamuri S., et al. (2004). Human microRNA genes are frequently located at fragile sites and genomic regions involved in cancers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 2999–3004 10.1073/pnas.0307323101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron J. E., Yin Q., Fewell C., Lacey M., McBride J., Wang X., et al. (2008). Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 induces cellular MicroRNA miR-146a, a modulator of lymphocyte signaling pathways. J Virol. 82 1946–1958 10.1128/JVI.02136-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. (2013). Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 368 2059–2074 10.1056/NEJMoa1301689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll A. P., Goodall G. J., Liu B. (2014). Understanding principles of miRNA target recognition and function through integrated biological and bioinformatics approaches. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 5 361–379 10.1002/wrna.1217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri A. A., So A. Y., Mehta A., Minisandram A., Sinha N., Jonsson V. D., et al. (2012). Oncomir miR-125b regulates hematopoiesis by targeting the gene Lin28A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 4233–4238 10.1073/pnas.1200677109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. Z., Li L., Lodish H. F., Bartel D. P. (2004). MicroRNAs modulate hematopoietic lineage differentiation. Science 303 83–86 10.1126/science.1091903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Liu Y., Rappaport A. R., Kitzing T., Schultz N., Zhao Z., et al. (2014). MLL3 is a haploinsufficient 7q tumor suppressor in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell 25 652–665 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J., Guo S., Chen S., Mastriano S. J., Liu C., D’Alessio A. C., et al. (2013). An extensive network of TET2-targeting MicroRNAs regulates malignant hematopoiesis. Cell Rep. 5 471–481 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.08.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu S. H., Heiser D., Li L., Kaplan I., Collector M., Huso D., et al. (2012). FLT3-ITD knockin impairs hematopoietic stem cell quiescence/homeostasis, leading to myeloproliferative neoplasm. Cell Stem Cell 11 346–358 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S. S., Hu W., Park C. Y. (2011). The role of micrornas in hematopoietic stem cell and leukemic stem cell function. Ther. Adv. Hematol. 23 17–334 10.1177/2040620711410772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croce C. M. (2008). Oncogenes and cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 358 502–511 10.1056/NEJMra072367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlhaus M., Roolf C., Ruck S., Lange S., Freund M., Junghanss C. (2013). Expression and prognostic significance of hsa-miR-142-3p in acute leukemias. Neoplasma 60 432–438 10.4149/neo_2013_056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damen J. E., Liu L., Rosten P., Humphries R. K., Jefferson A. B., Majerus P. W., et al. (1996). The 145-kDa protein induced to associate with Shc by multiple cytokines is an inositol tetraphosphate and phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate 5-phosphatase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93 1689–1693 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delhommeau F., Dupont S., Della Valle V., James C., Trannoy S., Massé A., et al. (2009). Mutation in TET2 in myeloid cancers. N. Engl. J. Med. 360 2289–2301 10.1056/NEJMoa0810069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deneault E., Cellot S., Faubert A., Laverdure J. P., Fréchette M., Chagraoui J., et al. (2009). A functional screen to identify novel effectors of hematopoietic stem cell activity. Cell 137 369–379 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-McIver A., East P., Mein C. A., Cazier J. B., Molloy G., Chaplin T., et al. (2008). Distinctive patterns of microRNA expression associated with karyotype in acute myeloid leukaemia. PLoS ONE 3:e2141 10.1371/journal.pone.0002141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou L., Li J., Zheng D., Li Y., Gao X., Xu C., et al. (2013). MicroRNA-142-3p inhibits cell proliferation in human acute lymphoblastic leukemia by targeting the MLL-AF4 oncogene. Mol. Biol. Rep. 40 6811–6819 10.1007/s11033-013-2798-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert B. L., Pretz J., Bosco J., Chang C. Y., Tamayo P., Galili N., et al. (2008). Identification of RPS14 as a 5q-syndrome gene by RNA interference screen. Nature 451 335–339 10.1038/nature06494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert M. S., Sharp P. A. (2010). MicroRNA sponges: progress and possibilities. RNA 16 2043–2050 10.1261/rna.2414110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eis P. S., Tam W., Sun L., Chadburn A., Li Z., Gomez M. F., et al. (2005). Accumulation of miR-155 and BIC RNA in human B cell lymphomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 3627–3632 10.1073/pnas.0500613102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmen J., Thonberg H., Ljungberg K., Frieden M., Westergaard M., Xu Y., et al. (2005). Locked nucleic acid (LNA) mediated improvements in siRNA stability and functionality. Nucleic Acids Res. 33 439–447 10.1093/nar/gki193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto Y., Kitaura J., Shimanuki M., Kato N., Nishimura K., Takahashi M., et al. (2012). MicroRNA-125b-1 accelerates a C-terminal mutant of C/EBPalpha (C/EBPalpha-C(m))-induced myeloid leukemia. Int. J. Hematol. 96 334–341 10.1007/s12185-012-1143-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etzrodt M., Cortez-Retamozo V., Newton A., Zhao J., Ng A., Wildgruber M., et al. (2012). Regulation of monocyte functional heterogeneity by miR-146a and Relb. Cell Rep. 1 317–324 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazi F., Rosa A., Fatica A., Gelmetti V., De Marchis M. L., Nervi C., et al. (2005). A minicircuitry comprised of microRNA-223 and transcription factors NFI-A and C/EBPalpha regulates human granulopoiesis. Cell 123 819–831 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felli N., Fontana L., Pelosi E., Botta R., Bonci D., Facchiano F., et al. (2005). MicroRNAs 221 and 222 inhibit normal erythropoiesis and erythroleukemic cell growth via kit receptor down-modulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 18081–18086 10.1073/pnas.0506216102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]