Abstract

The calculation of binding free energies of charged species to a target molecule is a frequently encountered problem in molecular dynamics studies of (bio-)chemical thermodynamics. Many important endogenous receptor-binding molecules, enzyme substrates, or drug molecules have a nonzero net charge. Absolute binding free energies, as well as binding free energies relative to another molecule with a different net charge will be affected by artifacts due to the used effective electrostatic interaction function and associated parameters (e.g., size of the computational box). In the present study, charging contributions to binding free energies of small oligoatomic ions to a series of model host cavities functionalized with different chemical groups are calculated with classical atomistic molecular dynamics simulation. Electrostatic interactions are treated using a lattice-summation scheme or a cutoff-truncation scheme with Barker–Watts reaction-field correction, and the simulations are conducted in boxes of different edge lengths. It is illustrated that the charging free energies of the guest molecules in water and in the host strongly depend on the applied methodology and that neglect of correction terms for the artifacts introduced by the finite size of the simulated system and the use of an effective electrostatic interaction function considerably impairs the thermodynamic interpretation of guest-host interactions. Application of correction terms for the various artifacts yields consistent results for the charging contribution to binding free energies and is thus a prerequisite for the valid interpretation or prediction of experimental data via molecular dynamics simulation. Analysis and correction of electrostatic artifacts according to the scheme proposed in the present study should therefore be considered an integral part of careful free-energy calculation studies if changes in the net charge are involved. © 2013 The Authors Journal of Computational Chemistry Published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Keywords: computer simulation, molecular dynamics, free-energy calculations, charging free energies, electrostatic artifacts

Introduction

The calculation of binding free energies is a standard task in the thermodynamic analysis of multicomponent molecular systems involving an association reaction between two system constituents, as, for example, an enzyme and a substrate, a receptor and a drug, or a nanocage and a guest compound. Physics-based approaches to compute binding free energies rely on statistical mechanics, which expresses the free energy as the natural logarithm of the system partition function (multiplied by the negative of the thermal energy, , where kB is Boltzmann's constant). The underlying configurational ensembles can be generated by, for example, molecular dynamics (MD) simulation. A wealth of methodological improvements, along with increased computational resources allow (in principle) the accurate calculation of binding free energies, as extensively reviewed in the case of protein-ligand association.1–9 However, if conducted without a proper eye on all potential pitfalls, binding free energies may be spuriously affected by limitations of MD simulations, such as, for example, an inadequate force-field description, approximations or/and assumptions in the free-energy calculation methodology, insufficient configurational sampling, or spurious configurational sampling due to the use of an effective electrostatic interaction function. These points are briefly discussed in turn below.

, where kB is Boltzmann's constant). The underlying configurational ensembles can be generated by, for example, molecular dynamics (MD) simulation. A wealth of methodological improvements, along with increased computational resources allow (in principle) the accurate calculation of binding free energies, as extensively reviewed in the case of protein-ligand association.1–9 However, if conducted without a proper eye on all potential pitfalls, binding free energies may be spuriously affected by limitations of MD simulations, such as, for example, an inadequate force-field description, approximations or/and assumptions in the free-energy calculation methodology, insufficient configurational sampling, or spurious configurational sampling due to the use of an effective electrostatic interaction function. These points are briefly discussed in turn below.

First, besides intrinsic deficiencies of classical force fields such as, for example, the neglect or mean-field treatment of electronic polarizability10,11 and the use of effective interaction energy functions12–14 with empirical parameters, additional problems arise if the system under consideration involves molecular species for which no force-field parameters are available. For instance, standard (bio-)molecular force fields may not provide parameterizations of certain metal ions, cofactors, or drug molecules. Ideally, the corresponding parameters should be parameterized against experimental data using a strategy consistent with the parameterization of the used force field. In practice, however, they are either inferred based on chemical intuition and comparison with similar compounds or taken from automatized parameterization protocols.15,16 In addition, although the solvent representation in most (bio-)molecular force fields is already highly simplistic (rigid three-site models17), its structural characteristics may be relinquished for the sake of computational savings, the solvent then being modeled implicitly and the solvent-generated electrostatic potential computed via numerical or empirical (generalized Born) solutions of the Poisson-Boltzmann equation.18–20

Second, because they rely on a thorough characterization of the phase space of the system, simulations involving free-energy calculations are computationally expensive, which is why a number of approximate methods are sometimes applied. For instance, the free energy of charging a neutral particle may be estimated from an electrostatic linear-response approximation21,22 or cumulant expansions at the endpoints of thermodynamic integration (TI).23–25 Similarly, the free energy of growing the van der Waals envelope of a particle is sometimes approximated using physics-based26,27 or empirical21 relationships. Furthermore, assumptions in the ansatz of free-energy calculation methods, such as, for example, sufficient overlap of the phase-space distribution functions in different states of relative free-energy calculations,28 or electrostatic linear response22,29 may limit the scope of their applicability. Lastly, discretization errors in numerical free-energy calculation methods, for example, the window width in potential of mean force calculations30,31 or the integration method in TI,32,33 limit the precision of the obtained results, although usage of optimal methods for statistical analysis [e.g., Bennett acceptance ratio (BAR)34,35 or multistate BAR36,37 approaches] may lead to significant gains in computational efficiency and statistical certainty.

Third, the phase space accessible to the system should be sampled exhaustively and according to the Gibbs measure appropriate for the desired thermodynamic ensemble, for example, canonical Boltzmann weighting in the case of simulations at constant particle number, temperature and volume. However, exhaustive sampling of phase space is complicated by the shear number of possible configurations, growing exponentially with the system size, and by energy barriers higher than , usually not amenable to transitions in plain MD simulation. Enhanced sampling methods can be used to improve coverage of the relevant phase space. A widely-used technique to address this problem involves the alteration of the potential energy function, for example, through local38,39 or nonlocal40,41 biasing, or more complex smoothening procedures,42,43 along with subsequent reweighting of the sampled configurations to the Gibbs measure corresponding to the unaltered potential energy function.

, usually not amenable to transitions in plain MD simulation. Enhanced sampling methods can be used to improve coverage of the relevant phase space. A widely-used technique to address this problem involves the alteration of the potential energy function, for example, through local38,39 or nonlocal40,41 biasing, or more complex smoothening procedures,42,43 along with subsequent reweighting of the sampled configurations to the Gibbs measure corresponding to the unaltered potential energy function.

Finally, even if the phase space accessible to the system is sampled exhaustively and according to the Gibbs measure appropriate for the desired thermodynamic ensemble, the sampled configurations might not be representative of the real (experimental) situation because of an approximate or incorrect calculation of interatomic interactions. This is generally the case for electrostatic interactions which, due their long-range nature, are treated in an effective manner during MD simulations.44–49 Ensuing artifacts become strongly apparent in the configurational sampling of systems involving charged particles or in free-energy calculations involving the change of the net charge of the system (charging free energy calculations), and have been reviewed extensively.48–56 For instance, if electrostatic interactions are calculated via lattice-summation (LS) over a periodic system in charging free energy calculations, the orientational polarization of the environment of the particle to be charged will be affected by the influence of the periodic copies of this particle, which is an inappropriate contribution if actually a truly nonperiodic system is to be described. The magnitude of the introduced errors may be strongly dependent on the parameters of the system or the interaction function (e.g., the box-edge length), giving rise to so-called methodology-dependent charging free energies.54 It has been shown before how charging free energies of monoatomic54,57,58 and polyatomic59–61 ions in infinitely dilute aqueous solution can be corrected for these errors, such that methodology-independent values are obtained.

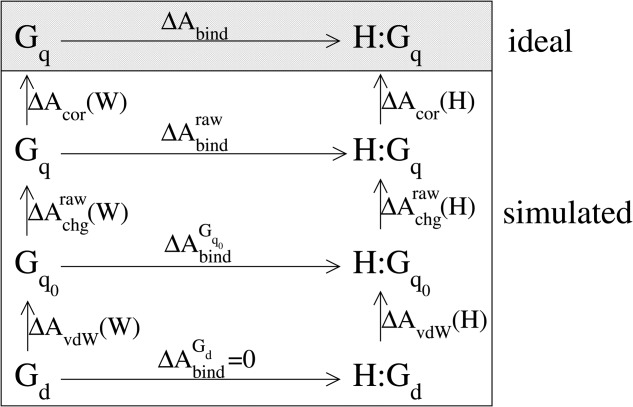

The goal of the present article is to address the last point above for model systems representative of a protein-ligand complex in aqueous solution, that is, to present a correction scheme for the charging of polyatomic ions in a low-dielectric cavity functionalized with different chemical groups (section “Simulated guest-host systems”), such that the raw charging free energy of a ligand bound to a host molecule can be corrected to a methodology-independent value

of a ligand bound to a host molecule can be corrected to a methodology-independent value (Fig. 1). Comparison with the corresponding raw or corrected charging free energies in bulk water,

(Fig. 1). Comparison with the corresponding raw or corrected charging free energies in bulk water, or

or , respectively, yields the raw or corrected binding free energies of the charged ligand to the host molecule relative to a neutralized analog of the ligand, in the following denoted as

, respectively, yields the raw or corrected binding free energies of the charged ligand to the host molecule relative to a neutralized analog of the ligand, in the following denoted as and

and , respectively (Fig. 1). The possible occurrence of methodology-dependent artifacts (caused by the use of an approximate electrostatic interaction function, an improper summation scheme and simulated systems of finite size) in

, respectively (Fig. 1). The possible occurrence of methodology-dependent artifacts (caused by the use of an approximate electrostatic interaction function, an improper summation scheme and simulated systems of finite size) in directly impairs calculations of the (absolute) binding free energy of a charged ligand and of relative binding free energies between ligands of different net charge. The value obtained for

directly impairs calculations of the (absolute) binding free energy of a charged ligand and of relative binding free energies between ligands of different net charge. The value obtained for is not representative of a macroscopic nonperiodic system with Coulombic electrostatic interactions, and only

is not representative of a macroscopic nonperiodic system with Coulombic electrostatic interactions, and only allows a meaningful comparison to or prediction of experimental data measured in systems of macroscopic extent (Fig. 1). This issue was, however, not duly appreciated in previous work. Examples from the authors' own research include, for example, the calculation of ligand binding free energies25,62,63 or redox potentials.64

allows a meaningful comparison to or prediction of experimental data measured in systems of macroscopic extent (Fig. 1). This issue was, however, not duly appreciated in previous work. Examples from the authors' own research include, for example, the calculation of ligand binding free energies25,62,63 or redox potentials.64

Figure 1.

Thermodynamic cycle illustrating the connection between the binding free energy of a noninteracting (dummy) guest molecule

of a noninteracting (dummy) guest molecule , the binding free energy

, the binding free energy of a neutral guest molecule

of a neutral guest molecule , the raw binding free energy

, the raw binding free energy of a charged guest molecule

of a charged guest molecule (full atomic partial charges), and the corrected binding free energy

(full atomic partial charges), and the corrected binding free energy of the latter guest to a host molecule H. Corresponding complexes formed by the host and the bound guest molecules are denoted H:G

of the latter guest to a host molecule H. Corresponding complexes formed by the host and the bound guest molecules are denoted H:G , H:G

, H:G , H:G

, H:G , and H:G

, and H:G , respectively. The free energies of growing the van der Waals envelope of the guest molecule,

, respectively. The free energies of growing the van der Waals envelope of the guest molecule, , raw free energies of charging,

, raw free energies of charging, , and correction terms,

, and correction terms, , of the guest in environment E (either water W or the host molecule H) are associated with the reversible work of creating neutral van der Waals particles (

, of the guest in environment E (either water W or the host molecule H) are associated with the reversible work of creating neutral van der Waals particles ( mutated into

mutated into ), installing partial charges (

), installing partial charges ( mutated into

mutated into ) and applying corrections for approximate-electrostatics, summation, and finite-size artifacts (

) and applying corrections for approximate-electrostatics, summation, and finite-size artifacts ( represented in the simulated situation associated with these artifacts versus in the ideal situation, i.e., a macroscopic nonperiodic system with Coulombic electrostatic interactions). The differences

represented in the simulated situation associated with these artifacts versus in the ideal situation, i.e., a macroscopic nonperiodic system with Coulombic electrostatic interactions). The differences and

and are the raw and corrected charging contributions to the binding free energy, that is, the raw and corrected binding free energies of the charged guest G

are the raw and corrected charging contributions to the binding free energy, that is, the raw and corrected binding free energies of the charged guest G relative to its neutralized analog G

relative to its neutralized analog G [eqs. (1) and (21)].

[eqs. (1) and (21)].

On the long term, increases in computational power as currently mainly driven by graphics processing unit-based electrostatic interaction calculation65–67 and advances in multiscale simulation methodologies targeted to an improved representation of electrostatic interactions68,69 may eventually allow for the simulation of macroscopic nonperiodic systems with Coulombic electrostatic interactions, or electrostatic interactions truncated at sufficiently large distances, such that an adequate representation of experimental bulk systems is achieved. Before such techniques have become state of the art, however, a scheme that corrects for methodology-induced artifacts will prove valuable in the calculation of binding free energies of charged ligands to (bio-)macromolecular host compounds.

Methods

Simulated guest-host systems

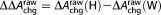

A previously described70 simplified guest-host system was used to assess the size of methodology-induced artifacts in the calculation of (relative) charging free energies (Table1). Two oppositely-charged guest molecules, methylammonium (MAM) and acetate (ACE), binding to a host C60 molecule (buckyball), or derivatives thereof, were considered. In comparison to a realistic buckyball model, here all C-C bonds were artificially extended to 0.2 nm. For the host molecules, four variants were used: (i) an empty, apolar C60 cavity (CAPO); (ii) a C60 cavity containing a covalently-bound amide group, representing a neutral polar cavity with hydrogen-bonding capability (CHB); (iii) a C60 cavity containing a covalently-bound methylammonium group, representing a positively-charged cavity (CPOS); (iv) a C60 cavity containing a covalently-bound carboxylate group, representing a negatively-charged cavity (CNEG). Because of the high symmetry and low flexibility in these systems, the observed artifacts can be expected to be solely due to methodological aspects rather than, in addition, insufficient sampling. Figure 2a provides a graphical illustration of an example guest-host complex used in the present study. GROMOS molecular topology71 files for the eight guest-host complexes are provided as supporting information.

Table 1.

Abbreviations used throughout the text for the names of guest molecules and chemical groups functionalizing the host cavity.

| Charge (e) | Abbreviation | |

|---|---|---|

| Guest | ||

| Methylammonium ion | 1.0 | MAM |

| Acetate ion | −1.0 | ACE |

| Host functionalization | ||

| – | 0 | CAPO |

| Formamide | 0 | CHB |

| Methylammonium | 1.0 | CPOS |

| Formate | −1.0 | CNEG |

Figure 2.

a) Stick representation of the guest-host complex MAM-CNEG. All guest-host complexes used in the present study are similarly composed of a noncovalently-bound oligoatomic ion (guest) and an artificial buckyball molecule possibly functionalized with a covalently-bound chemical group (host), as explained in section “Simulated guest-host systems.” In the following, they are depicted by a simplified schematic where the ion is drawn as a filled black circle and the buckyball is drawn as the gray surrounding structure. b) Graphic illustration of the meaning of correction terms ,

, ,

, , and

, and [eqs. (10), (11), (14), (15), (16), (17), (18)] to be applied to the raw charging free energy

[eqs. (10), (11), (14), (15), (16), (17), (18)] to be applied to the raw charging free energy [eq. (7)], for charging of a guest molecule in a solvated host to get a corrected charging free energy

[eq. (7)], for charging of a guest molecule in a solvated host to get a corrected charging free energy [eq. (20)] for the LS and BM electrostatic schemes. The guest, host, and water molecules are depicted in black, dark gray, and light gray colors, respectively. Periodic copies of the computational system are depicted with dashed lines. Arrows labeled with the above correction terms depict the concerned interactions, that is, guest-solvent interactions (

[eq. (20)] for the LS and BM electrostatic schemes. The guest, host, and water molecules are depicted in black, dark gray, and light gray colors, respectively. Periodic copies of the computational system are depicted with dashed lines. Arrows labeled with the above correction terms depict the concerned interactions, that is, guest-solvent interactions ( ,

, ), guest-host interactions (

), guest-host interactions ( ), and environment-mediated guest-guest interactions (

), and environment-mediated guest-guest interactions ( ). [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

). [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

The raw charging component of binding free energies of charged guests MAM and ACE to host molecules CAPO, CHB, CPOS, and CNEG was calculated with MD simulation according to a thermodynamic cycle (Fig. 1) involving the free energies of guest-charging in water

of binding free energies of charged guests MAM and ACE to host molecules CAPO, CHB, CPOS, and CNEG was calculated with MD simulation according to a thermodynamic cycle (Fig. 1) involving the free energies of guest-charging in water and in the host cavity

and in the host cavity ,

,

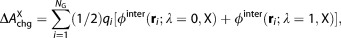

| 1 |

The MD simulations involved cubic computational boxes containing one guest molecule at multiple charge states qG varying from 0.0 to the full charges or

or for MAM and ACE, respectively, in either pure water or the hydrated host cavity. Each system was simulated in four different box sizes of edge lengths

for MAM and ACE, respectively, in either pure water or the hydrated host cavity. Each system was simulated in four different box sizes of edge lengths , and Ll, of about 2.46–2.53, 2.90, 3.21–3.25, or 3.80–3.81 nm, respectively, differing by the number of water molecules. Furthermore, two different methods were used to calculate electrostatic interactions (section “MD simulations”), namely either LS72,73 or molecule-based cutoff truncation in combination with a Barker–Watts reaction-field correction74 (BM). Simulations with the LS scheme were performed in boxes of edge length

, and Ll, of about 2.46–2.53, 2.90, 3.21–3.25, or 3.80–3.81 nm, respectively, differing by the number of water molecules. Furthermore, two different methods were used to calculate electrostatic interactions (section “MD simulations”), namely either LS72,73 or molecule-based cutoff truncation in combination with a Barker–Watts reaction-field correction74 (BM). Simulations with the LS scheme were performed in boxes of edge length , and Ll, and are in the following referred to as LS,ss, LS,s, LS,m, and LS,l, respectively. Simulations with the BM scheme were performed in boxes of edge length Lm and Ll, and are in the following referred to as BM,m and BM,l, respectively.

, and Ll, and are in the following referred to as LS,ss, LS,s, LS,m, and LS,l, respectively. Simulations with the BM scheme were performed in boxes of edge length Lm and Ll, and are in the following referred to as BM,m and BM,l, respectively.

MD simulations

All MD simulations were performed either with a modified version of the GROMOS96 program71 or with the GROMOS11 program.75 The former was exclusively used for free-energy calculations in simulations using the particle-particle-particle-mesh (P3M) method72,73 for the treatment of electrostatic interactions. Water was represented by means of the three-site simple point charge (SPC) model.76 Host and guest molecules were described with the GROMOS 53A6 force-field parameter set as in the previous study of Ref.70. For CNEG, the appropriate GROMOS improper dihedral type 1 (reference value of 0°) was used for the improper dihedral angle in the formate group rather than an erroneous type 2 (reference value of 35° as in Ref.70).

All simulations were carried out under periodic boundary conditions (PBC) based on cubic computational boxes. The equations of motion were integrated using the leap-frog scheme77 with a timestep of 2 fs. The solute bond-length distances and the rigidity of the water molecules were enforced by application of the SHAKE algorithm78 with a relative geometric tolerance of 10−4. The center of mass translation of the computational box was removed every 2 ps. The temperature was maintained at 300 K by weak coupling to a heat bath79 using a coupling time of 0.1 ps and the volume was kept constant. Electrostatic interactions were either calculated using LS based on the P3M algorithm with tinfoil boundary conditions,72,73 or using the BM scheme.74 The LS scheme was applied with72,80,81 a spherical hat charge-shaping function of width 1.0 nm, a triangular shaped cloud assignment function, a finite-difference (FD) scheme of order two and a grid spacing of about 0.08–0.12 nm in the different systems. The self-energy term23,73,82–84 of the guest molecule was not included in the electrostatic potential at the guest atom sites to be consistent with the previously developed correction scheme for single-ion solvation free energies.54,57 In simulations with the LS scheme, Lennard–Jones interactions were truncated at an atom-based cutoff distance . Both real-space electrostatic and Lennard–Jones interactions were calculated at each timestep based on a pairlist updated at each timestep. The BM scheme was applied with a value

. Both real-space electrostatic and Lennard–Jones interactions were calculated at each timestep based on a pairlist updated at each timestep. The BM scheme was applied with a value for the relative permittivity of the dielectric continuum surrounding the cutoff sphere, as appropriate85 for the SPC water model. Here, too, the self-energy term84,86 of the guest molecule was not included in the calculation of the electrostatic potential at the guest atom sites to be consistent with previous work.54,57 In simulations with the BM scheme, electrostatic and Lennard–Jones (van der Waals) interactions were truncated at a charge-group cutoff distance

for the relative permittivity of the dielectric continuum surrounding the cutoff sphere, as appropriate85 for the SPC water model. Here, too, the self-energy term84,86 of the guest molecule was not included in the calculation of the electrostatic potential at the guest atom sites to be consistent with previous work.54,57 In simulations with the BM scheme, electrostatic and Lennard–Jones (van der Waals) interactions were truncated at a charge-group cutoff distance , and calculated at each timestep based on a pairlist that was updated at each timestep.

, and calculated at each timestep based on a pairlist that was updated at each timestep.

The calculation of the charging component to the binding free energy was performed in two TI procedures87 considering the free energies of charging the guest molecules in water and in the host cavity (Fig. 1). All production simulations for the free-energy calculations were preceded by an equilibration period of 0.3 ns and lasted 1 ns. The configurations sampled along these simulations were written to file every 0.3 ps for subsequent analysis, whereas the corresponding energetic data was written every timestep.

Structural properties

The configurations sampled in simulations LS,ss, LS,l, and BM,l of the fully charged guests MAM and ACE in hydrated host molecules CAPO, CHB, CPOS, and CNEG were analyzed in terms of the solvent radial distribution function g(r) around the buckyball center of mass, and the solvent radial polarization P(r) around the charged guest. These functions were calculated as

| 2 |

and

| 3 |

where denotes ensemble averaging,

denotes ensemble averaging, is the solvent number density,

is the solvent number density, is the number of water molecules j for which

is the number of water molecules j for which (

( denoting all possible minimum-image vectors connecting the center of mass of the 60 buckyball carbon atoms to the oxygen atom of any periodic copy of water molecule j),

denoting all possible minimum-image vectors connecting the center of mass of the 60 buckyball carbon atoms to the oxygen atom of any periodic copy of water molecule j), is the number of water molecules j for which

is the number of water molecules j for which (

( here denoting all possible minimum-image vectors connecting the MAM nitrogen atom or the ACE carboxylate carbon atom to the oxygen atom of any periodic copy of water molecule j),

here denoting all possible minimum-image vectors connecting the MAM nitrogen atom or the ACE carboxylate carbon atom to the oxygen atom of any periodic copy of water molecule j),

| 4 |

is the bin width,

is the bin width, is the molecular dipole moment of the SPC water model76 and

is the molecular dipole moment of the SPC water model76 and is defined as

is defined as

| 5 |

being a unit vector along the dipole moment of molecule j. For systems MAM-CAPO, MAM-CHB, MAM-CPOS, ACE-CAPO, ACE-CHB, and ACE-CNEG, P(r) was compared to a radial continuum-electrostatics analog, here approximated by the Born polarization

being a unit vector along the dipole moment of molecule j. For systems MAM-CAPO, MAM-CHB, MAM-CPOS, ACE-CAPO, ACE-CHB, and ACE-CNEG, P(r) was compared to a radial continuum-electrostatics analog, here approximated by the Born polarization around a charge of

around a charge of (MAM-CAPO, MAM-CHB),

(MAM-CAPO, MAM-CHB), (MAM-CPOS),

(MAM-CPOS), (ACE-CAPO, ACE-CHB), or

(ACE-CAPO, ACE-CHB), or (ACE-CNEG) centered at the MAM nitrogen or the ACE carboxylate carbon atom,

(ACE-CNEG) centered at the MAM nitrogen or the ACE carboxylate carbon atom,

| 6 |

where is the relative dielectric permittivity of the SPC water model.85 Equation (6) is an approximation because in the considered systems the charge

is the relative dielectric permittivity of the SPC water model.85 Equation (6) is an approximation because in the considered systems the charge is actually spread out over multiple atom sites. In addition, the dielectric permittivity around the highly-charged MAM-CPOS and ACE-CNEG systems may be lower than the bulk value of 66.6.

is actually spread out over multiple atom sites. In addition, the dielectric permittivity around the highly-charged MAM-CPOS and ACE-CNEG systems may be lower than the bulk value of 66.6.

Free-energy calculations

Raw charging free energy

Raw charging free energies and

and [eq. (1)] were calculated with the TI approach87 along progressive installation of λ-dependent intermolecular electrostatic interactions

[eq. (1)] were calculated with the TI approach87 along progressive installation of λ-dependent intermolecular electrostatic interactions ,

,

| 7 |

where the subscript E denotes the environment of the guest (either W or H), denotes the

denotes the -dimensional coordinate vector of the system containing

-dimensional coordinate vector of the system containing guest atoms and

guest atoms and water and host atoms, λ denotes the scaling parameter of the TI procedure, and

water and host atoms, λ denotes the scaling parameter of the TI procedure, and denotes ensemble averaging over configurations sampled during a simulation where the guest is in environment E, and guest partial atom charges are scaled by λ. The term

denotes ensemble averaging over configurations sampled during a simulation where the guest is in environment E, and guest partial atom charges are scaled by λ. The term in eq. (7) was calculated based on the sampled configurations as

in eq. (7) was calculated based on the sampled configurations as

| 8 |

where is the permittivity of vacuum and qi is the partial charge of atom i.

is the permittivity of vacuum and qi is the partial charge of atom i. is the effective pairwise electrostatic interaction function which describes the implementation of the particular electrostatics scheme.71 The exact details of this function depend on the implementation in a simulation program, and can be found elsewhere.71,86 Note that the electrostatic interaction energy

is the effective pairwise electrostatic interaction function which describes the implementation of the particular electrostatics scheme.71 The exact details of this function depend on the implementation in a simulation program, and can be found elsewhere.71,86 Note that the electrostatic interaction energy is exempt of intramolecular contributions.

is exempt of intramolecular contributions.

During the simulations of a given charge state, the partial charges of the guest atoms were scaled by λ. For all free-energy estimates, eleven charge states ( , 0.1, …, 0.9, 1.0) were used and, the integral in eq. (7) was evaluated numerically with the trapezoidal rule. Statistical error estimates on ensemble averages pertaining to particular λ-values were obtained from block averaging.88 Errors on the free-energy values were calculated by numerical integration (trapezoidal rule) of the individual errors and amounted to about 0.2–1.9 kJ mol−1.

, 0.1, …, 0.9, 1.0) were used and, the integral in eq. (7) was evaluated numerically with the trapezoidal rule. Statistical error estimates on ensemble averages pertaining to particular λ-values were obtained from block averaging.88 Errors on the free-energy values were calculated by numerical integration (trapezoidal rule) of the individual errors and amounted to about 0.2–1.9 kJ mol−1.

Free-energy correction terms

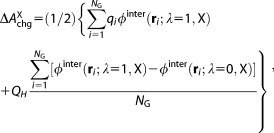

The raw charging free energies [eq. (7)] were used to calculate corresponding methodology-independent values

[eq. (7)] were used to calculate corresponding methodology-independent values as54,57,58

as54,57,58

| 9 |

where is a free-energy correction for the various methodology-dependent errors committed during the simulation. These errors have been discussed extensively for the case of monoatomic54,56,58 and polyatomic61 single-ion hydration. In simulations with the LS and BM schemes, they arise from:

is a free-energy correction for the various methodology-dependent errors committed during the simulation. These errors have been discussed extensively for the case of monoatomic54,56,58 and polyatomic61 single-ion hydration. In simulations with the LS and BM schemes, they arise from:

The deviation of the solvent polarization around the charged solute from the polarization in an ideal macroscopic system with Coulombic electrostatic interactions. This is a consequence of the use of a finite (microscopic) system during the simulation, for example, a computational box simulated under PBC, of the use of approximate (non-Coulombic in the limit of infinite system sizes) electrostatic interaction functions, for example, involving cutoff truncation, and of the use of a solvent model with an inaccurate dielectric permittivity. The corresponding correction term is here denoted

. Note that in previous work,61 this correction term was denoted

. Note that in previous work,61 this correction term was denoted , or split up into three terms54,57,58

, or split up into three terms54,57,58 , and

, and .

.The deviation of the solvent-generated electrostatic potential at the atom sites of the charged solute as calculated from the simulated trajectory from the “correct” electrostatic potential. This is a consequence of the possible application of an inappropriate summation scheme for the contributions of individual solvent atomic charges to this potential, that is, summing over individual point charges (“P-summation”89) versus summing over charges within individual solvent molecules (“M-summation”89), as well as of the possible presence of a constant offset in this potential, due to the presence of an interfacial potential at the surface of the solute along with the constraint of vanishing average potential in the LS scheme. The corresponding correction term is here denoted

. Note that in previous work,54,57,58,61 this correction term was denoted

. Note that in previous work,54,57,58,61 this correction term was denoted .

.The spurious calculation of guest-host interactions with an effective electrostatics scheme rather than with Coulombic electrostatic interactions. The corresponding correction term is denoted

. Note that it is only pertinent to systems containing the host moiety, that is, it only occurs in

. Note that it is only pertinent to systems containing the host moiety, that is, it only occurs in .

.The presence of electrostatic interactions between excluded atoms in the guest molecule. The corresponding correction term is denoted

. Note that it is absent in the case of monoatomic guest compounds and that it was not explicitly listed in Ref.61, because there these interactions were considered an integral part of the environment-induced electrostatic potential at the solute atoms.

. Note that it is absent in the case of monoatomic guest compounds and that it was not explicitly listed in Ref.61, because there these interactions were considered an integral part of the environment-induced electrostatic potential at the solute atoms.

Figure 2b illustrates the interactions addressed by the afore mentioned correction terms ,

, , and

, and for the case of a guest molecule binding noncovalently to a solvated host. In the following, the calculation of these terms is explained.

for the case of a guest molecule binding noncovalently to a solvated host. In the following, the calculation of these terms is explained.

As in previous work,61 can be deduced from the results of two continuum-electrostatics calculations,

can be deduced from the results of two continuum-electrostatics calculations,

| 10 |

for the LS scheme and

| 11 |

for the BM scheme, where is the charging free energy of the guest molecule in a macroscopic nonperiodic system with Coulombic electrostatic interactions based on the experimental solvent permittivity (CB).

is the charging free energy of the guest molecule in a macroscopic nonperiodic system with Coulombic electrostatic interactions based on the experimental solvent permittivity (CB). and

and are the charging free energies of the guest molecule in a periodic system with LS or BM electrostatic interactions based on the model solvent permittivity, respectively. Here, the relative dielectric permittivity is set to 66.6 in the calculation of

are the charging free energies of the guest molecule in a periodic system with LS or BM electrostatic interactions based on the model solvent permittivity, respectively. Here, the relative dielectric permittivity is set to 66.6 in the calculation of and

and as appropriate for the SPC water model85 and to 78.4 in the calculation of

as appropriate for the SPC water model85 and to 78.4 in the calculation of , as appropriate for water,56 to account for the inaccurate dielectric permittivity of the SPC water model. As the guest molecules considered in this study are essentially rigid,

, as appropriate for water,56 to account for the inaccurate dielectric permittivity of the SPC water model. As the guest molecules considered in this study are essentially rigid, and

and are essentially configuration-independent. Also, the rotational and translational sampling of the guest molecules in the host cavities does not lead to significant fluctuations in

are essentially configuration-independent. Also, the rotational and translational sampling of the guest molecules in the host cavities does not lead to significant fluctuations in (data not shown). Therefore, the calculations of

(data not shown). Therefore, the calculations of ,

, , and

, and were only performed based on a single structure, taken as the final solute configuration of the simulation at guest charge states

were only performed based on a single structure, taken as the final solute configuration of the simulation at guest charge states in the system with box-edge length Ll, as

in the system with box-edge length Ll, as

| 12 |

where , LS, or BM, and

, LS, or BM, and is the environment-generated electrostatic potential evaluated at guest atom site i and charge state λ for the given boundary conditions and electrostatics scheme X. For both the LS and BM scheme,

is the environment-generated electrostatic potential evaluated at guest atom site i and charge state λ for the given boundary conditions and electrostatics scheme X. For both the LS and BM scheme, was evaluated using the FD Poisson equation solver of Refs.90–92 with the appropriate boundary conditions, and solvent permittivity. The FD solver was also used to evaluate

was evaluated using the FD Poisson equation solver of Refs.90–92 with the appropriate boundary conditions, and solvent permittivity. The FD solver was also used to evaluate . Because the FD solver does not offer the option of using the BM scheme, a combination with the fast fourier transform (FFT) Poisson equation solver of Refs.93–94 was used to evaluate

. Because the FD solver does not offer the option of using the BM scheme, a combination with the fast fourier transform (FFT) Poisson equation solver of Refs.93–94 was used to evaluate as

as

| 13 |

where the first and the last two terms on the right-hand side are calculated based on the FD and FFT Poisson equation solvers, respectively. This is done to enhance cancellation of grid-discretization and boundary-smoothing errors in the two different Poisson equation solvers. In both algorithms, the grid spacing was set to about 0.02 nm and the convergence threshold for the electrostatic free energy was set to . A van der Waals envelope was used to define the guest-host system, where the atomic radii were based on distances at the minimum of the Lennard–Jones potential between the different solute atoms and the oxygen atom of a SPC water molecule76 using the Lennard–Jones interaction parameters of the GROMOS 53A6 force-field parameter set,95 reduced by an estimate96 for the radius of a water molecule (0.14 nm). Polar hydrogen atoms were treated differently53,55 and assigned an atomic radius of 0.05 nm. Instead of using eq. (12) to evaluate

. A van der Waals envelope was used to define the guest-host system, where the atomic radii were based on distances at the minimum of the Lennard–Jones potential between the different solute atoms and the oxygen atom of a SPC water molecule76 using the Lennard–Jones interaction parameters of the GROMOS 53A6 force-field parameter set,95 reduced by an estimate96 for the radius of a water molecule (0.14 nm). Polar hydrogen atoms were treated differently53,55 and assigned an atomic radius of 0.05 nm. Instead of using eq. (12) to evaluate , less computationally intensive but more approximate approaches can be used, which are discussed in Appendix section “Calculation of

, less computationally intensive but more approximate approaches can be used, which are discussed in Appendix section “Calculation of ”.

”.

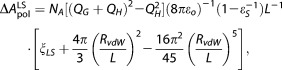

The term corrects for the atom-based summation scheme implied by the LS and BM schemes in comparison to a proper molecule-based summation scheme.89 In the present study, it is calculated as

corrects for the atom-based summation scheme implied by the LS and BM schemes in comparison to a proper molecule-based summation scheme.89 In the present study, it is calculated as

| 14 |

for the LS scheme and

| 15 |

for the BM scheme, where NA is Avogadro's constant, is the quadrupole-moment trace of the water model relative to its single van der Waals interaction site, Nw is the number of water molecules,

is the quadrupole-moment trace of the water model relative to its single van der Waals interaction site, Nw is the number of water molecules, the reaction-field permittivity, RC the cutoff distance, L3 the box volume (here, a constant box-edge length L is adopted because all simulations were performed at constant volume), and

the reaction-field permittivity, RC the cutoff distance, L3 the box volume (here, a constant box-edge length L is adopted because all simulations were performed at constant volume), and is the average number of water molecules present within the cutoff sphere around the center of mass of the 60 buckyball carbon atoms for in-host charging, or around the MAM nitrogen or ACE carboxylate carbon atoms in the case of in-water charging. For the SPC water model,76,89

is the average number of water molecules present within the cutoff sphere around the center of mass of the 60 buckyball carbon atoms for in-host charging, or around the MAM nitrogen or ACE carboxylate carbon atoms in the case of in-water charging. For the SPC water model,76,89 . Equation (15) differs from the equation used in Ref.61 for the calculation of

. Equation (15) differs from the equation used in Ref.61 for the calculation of . The corresponding equation used in Ref.61, as well a derivation of eq. (15) and a comparison in terms of root-mean-square deviations of corrected charging free energies are reported in Appendix section “Calculation of

. The corresponding equation used in Ref.61, as well a derivation of eq. (15) and a comparison in terms of root-mean-square deviations of corrected charging free energies are reported in Appendix section “Calculation of ”.

”.

The additional contribution to related to the quadrupole-moment trace of the guest and host molecules is implicitly accounted for through the presence of these molecules in the continuum-electrostatics calculations [eq. (12)], because the boundary conditions in the FD Poisson solver calculations under PBC enforce zero average electrostatic potential over the computational box, which is equivalent to the situation in the MD simulations. On the contrary, in the FD Poisson solver calculations under nonperiodic boundary conditions (NPBC), there is no such shifting of the average electrostatic potential. That means that the correction

related to the quadrupole-moment trace of the guest and host molecules is implicitly accounted for through the presence of these molecules in the continuum-electrostatics calculations [eq. (12)], because the boundary conditions in the FD Poisson solver calculations under PBC enforce zero average electrostatic potential over the computational box, which is equivalent to the situation in the MD simulations. On the contrary, in the FD Poisson solver calculations under nonperiodic boundary conditions (NPBC), there is no such shifting of the average electrostatic potential. That means that the correction , which involves a difference between calculations under NPBC and PBC [eqs. (10) and (11)] also corrects for the spurious vanishing average (over the computational box) electrostatic potential contribution due to the guest and host quadrupole moments in the MD simulations. Note that this implicit inclusion of the solute-associated

, which involves a difference between calculations under NPBC and PBC [eqs. (10) and (11)] also corrects for the spurious vanishing average (over the computational box) electrostatic potential contribution due to the guest and host quadrupole moments in the MD simulations. Note that this implicit inclusion of the solute-associated correction in

correction in was not recognized in previous work.61

was not recognized in previous work.61

Similar to Ref.61, the term was neglected in the present study because this term is proportional to the ratio of the guest volume to the box volume, that is, its magnitude is very small for the systems considered here.

was neglected in the present study because this term is proportional to the ratio of the guest volume to the box volume, that is, its magnitude is very small for the systems considered here.

The term , to be applied only to raw charging free energies of the guest in the host, was calculated as

, to be applied only to raw charging free energies of the guest in the host, was calculated as

| 16 |

and

| 17 |

where ,

, , and

, and are charging free energies of the guest due to the host calculated with Coulombic electrostatic interactions in a nonperiodic system and with effective electrostatic interactions (LS or BM) under PBC, respectively. The guest-host complex configurations sampled in the explicit-water MD simulations at all guest charge states

are charging free energies of the guest due to the host calculated with Coulombic electrostatic interactions in a nonperiodic system and with effective electrostatic interactions (LS or BM) under PBC, respectively. The guest-host complex configurations sampled in the explicit-water MD simulations at all guest charge states (section “Raw charging free energy”) were used to extract

(section “Raw charging free energy”) were used to extract , and

, and in postanalyses under NPBC (guest-host complex in vacuum described with Coulombic electrostatic interactions) and under PBC (guest-host complex described with LS or BM electrostatic interactions), respectively (section “Solute and solvent contributions to the free energy of charging”).

in postanalyses under NPBC (guest-host complex in vacuum described with Coulombic electrostatic interactions) and under PBC (guest-host complex described with LS or BM electrostatic interactions), respectively (section “Solute and solvent contributions to the free energy of charging”).

The term was calculated as

was calculated as

| 18 |

where is a modified LS or BM electrostatic interaction function exempt of self term. The integrand of eq. (18) corresponds to minus the first term in eq. (20) of Ref.61 and corrects for the presence of electrostatic interactions between excluded atoms (first and second covalently-bound neighbors) in the Hamiltonian used in the present simulations. Electrostatic interactions between excluded atoms are equal to the normal interaction function applied to nonexcluded atoms, but reduced by the Coulombic contribution. As a result, excluded atoms may be viewed to interact via a term that depends on the representation of the surroundings of the solute, that is, periodic copies of the computational box in the case of the LS scheme and a continuous medium of homogeneous relative dielectric permittivity in the case of the BM scheme. Therefore, in the present study, interactions between excluded atoms are regarded as contributing in a methodologically-dependent way to the charging free energy. Application of

is a modified LS or BM electrostatic interaction function exempt of self term. The integrand of eq. (18) corresponds to minus the first term in eq. (20) of Ref.61 and corrects for the presence of electrostatic interactions between excluded atoms (first and second covalently-bound neighbors) in the Hamiltonian used in the present simulations. Electrostatic interactions between excluded atoms are equal to the normal interaction function applied to nonexcluded atoms, but reduced by the Coulombic contribution. As a result, excluded atoms may be viewed to interact via a term that depends on the representation of the surroundings of the solute, that is, periodic copies of the computational box in the case of the LS scheme and a continuous medium of homogeneous relative dielectric permittivity in the case of the BM scheme. Therefore, in the present study, interactions between excluded atoms are regarded as contributing in a methodologically-dependent way to the charging free energy. Application of removes the corresponding contribution.

removes the corresponding contribution.

Given the above correction terms, the charging free energy is calculated according to eq. (9) as the sum of the raw charging free energy

is calculated according to eq. (9) as the sum of the raw charging free energy , and the correction terms

, and the correction terms [eqs. (10) and (11)],

[eqs. (10) and (11)], [eqs. (14) and (15)],

[eqs. (14) and (15)], [eqs. (16) and (17)] and

[eqs. (16) and (17)] and [eq. (18)] as

[eq. (18)] as

| 19 |

in the case of charging in water, and as

| 20 |

in the case of charging in the host. These charging free energies were calculated for guests MAM and ACE in water and host molecules CAPO, CHB, CPOS, and CNEG and yield the corrected charging component of binding free energies of the guest to the host,

of binding free energies of the guest to the host,

| 21 |

Solute and solvent contributions to the free energy of charging

The trajectories of guest-host complexes were reanalyzed to obtain the raw free energy of charging the guest molecule due to the host and periodic host copies as

as

| 22 |

where , and

, and are the total electrostatic energies sampled in trajectories pertaining to guest charge states defined by λ using modified interaction parameters with full guest and host charges, full guest and zeroed host charges and zeroed guest and full host charges, respectively. The corresponding raw free energies of charging the guest molecule due to the solvent and periodic solvent copies

are the total electrostatic energies sampled in trajectories pertaining to guest charge states defined by λ using modified interaction parameters with full guest and host charges, full guest and zeroed host charges and zeroed guest and full host charges, respectively. The corresponding raw free energies of charging the guest molecule due to the solvent and periodic solvent copies are calculated as

are calculated as

| 23 |

where is given by eq. (7). Corrected values

is given by eq. (7). Corrected values and

and are calculated as the sum of the raw charging free energies and the correction term

are calculated as the sum of the raw charging free energies and the correction term [eqs. (16) and (17)],

[eqs. (16) and (17)],

| 24 |

in the case of , and as the sum of the raw charging free energies and the correction terms

, and as the sum of the raw charging free energies and the correction terms , and

, and [eqs. (10), (11), (14), (15), and (18)],

[eqs. (10), (11), (14), (15), and (18)],

| 25 |

in the case of .

.

Results

Application of correction terms for spurious solvent polarization and wrong dielectric permittivity of the solvent model ( ) [eqs. (10) and (11)], improper electrostatic potential summation (

) [eqs. (10) and (11)], improper electrostatic potential summation ( ) [eqs. (14) and (15)], effective guest-host direct electrostatic interactions (

) [eqs. (14) and (15)], effective guest-host direct electrostatic interactions ( ) [eqs. (16) and (17)] and the presence of electrostatic interactions between excluded solute atoms in the Hamiltonian (

) [eqs. (16) and (17)] and the presence of electrostatic interactions between excluded solute atoms in the Hamiltonian ( ) [eq. (18)] to raw charging free energies

) [eq. (18)] to raw charging free energies [eq. (7)] yields corrected values

[eq. (7)] yields corrected values [eqs. (19) and (20)] reported in Table2 for charging of guests MAM and ACE in water or in complex with the hydrated host molecules CAPO, CHB, CPOS, or CNEG (Table1). This is illustrated for four different sizes of the computational box (

[eqs. (19) and (20)] reported in Table2 for charging of guests MAM and ACE in water or in complex with the hydrated host molecules CAPO, CHB, CPOS, or CNEG (Table1). This is illustrated for four different sizes of the computational box ( and Ll) and the two different electrostatics schemes (LS and BM) considered (section “MD simulations”). While the root-mean-square deviations for

and Ll) and the two different electrostatics schemes (LS and BM) considered (section “MD simulations”). While the root-mean-square deviations for are 6.6, 6.8, 6.7, 8.1, and 9.0 kJ mol−1 for charging of MAM in CAPO, CHB, CPOS, CNEG, and water, respectively, and 12.4, 12.3, 11.8, 13.9, and 10.2 kJ mol−1 for charging of ACE in CAPO, CHB, CPOS, CNEG, and water, respectively, they are reduced to 0.8, 1.0, 1.5, 2.1, and 1.4 kJ mol−1 for MAM and 0.5, 0.6, 1.6, 2.5, and 0.6 kJ mol−1 for ACE in corresponding corrected free energies

are 6.6, 6.8, 6.7, 8.1, and 9.0 kJ mol−1 for charging of MAM in CAPO, CHB, CPOS, CNEG, and water, respectively, and 12.4, 12.3, 11.8, 13.9, and 10.2 kJ mol−1 for charging of ACE in CAPO, CHB, CPOS, CNEG, and water, respectively, they are reduced to 0.8, 1.0, 1.5, 2.1, and 1.4 kJ mol−1 for MAM and 0.5, 0.6, 1.6, 2.5, and 0.6 kJ mol−1 for ACE in corresponding corrected free energies . Complexes MAM-CNEG and ACE-CNEG exhibit the largest rmsd values in corrected charging free energies (2.1 and 2.5 kJ mol−1). Notably, for these complexes, the

. Complexes MAM-CNEG and ACE-CNEG exhibit the largest rmsd values in corrected charging free energies (2.1 and 2.5 kJ mol−1). Notably, for these complexes, the value from simulation LS,ss has higher magnitudes by up to 6.0 kJ mol−1 (MAM-CNEG) or up to 8.0 kJ mol−1 (ACE-CNEG) compared to simulations LS,s, LS,m, LS,l, BM,m, and BM,l. These deviations might be due to the inability of the continuum-electrostatics representation to capture short-range artifacts in solvent structure.

value from simulation LS,ss has higher magnitudes by up to 6.0 kJ mol−1 (MAM-CNEG) or up to 8.0 kJ mol−1 (ACE-CNEG) compared to simulations LS,s, LS,m, LS,l, BM,m, and BM,l. These deviations might be due to the inability of the continuum-electrostatics representation to capture short-range artifacts in solvent structure.

Table 2.

Charging free energies  of the guest molecules MAM and ACE in hydrated host molecules CAPO, CHB, CPOS, and CNEG, as well as in water, computed in cubic computational boxes of edge length L containing Nw water molecules using LS or BM electrostatic interactions (sections “Simulated guest-host systems“ and ”MD simulations”). Values obtained with the LS scheme in boxes of edge lengths

of the guest molecules MAM and ACE in hydrated host molecules CAPO, CHB, CPOS, and CNEG, as well as in water, computed in cubic computational boxes of edge length L containing Nw water molecules using LS or BM electrostatic interactions (sections “Simulated guest-host systems“ and ”MD simulations”). Values obtained with the LS scheme in boxes of edge lengths , and Ll are labeled LS,ss, LS,s, LS,m, and LS,l, respectively, and values obtained with the BM scheme in boxes of edge lengths Lm and Ll are labeled BM,m and BM,l, respectively. The charging free energy

, and Ll are labeled LS,ss, LS,s, LS,m, and LS,l, respectively, and values obtained with the BM scheme in boxes of edge lengths Lm and Ll are labeled BM,m and BM,l, respectively. The charging free energy [eqs. (19) and (20)] is calculated as a sum of the raw charging free energy

[eqs. (19) and (20)] is calculated as a sum of the raw charging free energy [eq. (7)], and the correction terms

[eq. (7)], and the correction terms , and

, and [eqs. (10), (11), (14), (15), (16), (17), (18)]. Error estimates on the raw charging free energies refer to the statistical uncertainty obtained from block averaging.88

[eqs. (10), (11), (14), (15), (16), (17), (18)]. Error estimates on the raw charging free energies refer to the statistical uncertainty obtained from block averaging.88

| Guest | Host/water | Scheme | Nw | L (nm) |

(kJ mol−1) (kJ mol−1) |

(kJ mol−1) (kJ mol−1) |

(kJ mol−1) (kJ mol−1) |

(kJ mol−1) (kJ mol−1) |

(kJ mol−1) (kJ mol−1) |

(kJ mol−1) (kJ mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAM | CAPO | LS,ss | 471 | 2.46 | −4.4± 0.2 | −71.2 | −75.4 | 0.0 | −0.2 | −151.2 |

| LS,s | 780 | 2.90 | −12.4± 0.2 | −62.4 | −76.3 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −151.2 | ||

| LS,m | 1095 | 3.24 | −17.6± 0.2 | −56.8 | −76.9 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −151.4 | ||

| LS,l | 1792 | 3.81 | −24.7± 0.2 | −49.2 | −77.1 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −151.1 | ||

| BM,m | 1095 | 3.24 | −8.5± 0.2 | −72.3 | −68.9 | 0.0 | −0.3 | −150.0 | ||

| BM,l | 1792 | 3.81 | −9.7± 0.2 | −71.3 | −67.8 | 0.0 | −0.3 | −149.1 | ||

| CHB | LS,ss | 469 | 2.46 | −38.7± 0.8 | −70.5 | −75.4 | −0.7 | −0.2 | −185.5 | |

| LS,s | 780 | 2.90 | −47.3± 0.9 | −61.8 | −76.3 | −0.4 | −0.1 | −185.9 | ||

| LS,m | 1095 | 3.24 | −53.2± 0.8 | −56.3 | −77.1 | −0.3 | −0.1 | −187.0 | ||

| LS,l | 1781 | 3.81 | −59.7± 0.9 | −48.9 | −77.3 | −0.2 | −0.1 | −186.2 | ||

| BM,m | 1095 | 3.24 | −44.1± 0.3 | −71.2 | −69.0 | −0.9 | −0.3 | −185.5 | ||

| BM,l | 1781 | 3.80 | −44.3± 0.3 | −70.2 | −68.0 | −0.9 | −0.3 | −183.7 | ||

| CPOS | LS,ss | 473 | 2.46 | 115.7± 0.5 | −209.7 | −75.4 | 155.8 | −0.2 | −13.8 | |

| LS,s | 780 | 2.90 | 111.2± 0.5 | −184.6 | −76.3 | 133.3 | −0.1 | −16.5 | ||

| LS,m | 1090 | 3.23 | 107.6± 0.6 | −168.6 | −76.9 | 120.0 | −0.1 | −18.0 | ||

| LS,l | 1772 | 3.80 | 102.8± 0.6 | −146.4 | −77.1 | 102.6 | −0.1 | −18.2 | ||

| BM,m | 1090 | 3.23 | 122.2± 0.5 | −212.8 | −69.1 | 142.4 | −0.3 | −17.6 | ||

| BM,l | 1772 | 3.80 | 119.7± 0.6 | −209.9 | −68.2 | 142.4 | −0.3 | −16.3 | ||

| CNEG | LS,ss | 473 | 2.46 | −234.2± 1.8 | 69.9 | −75.4 | −157.9 | −0.2 | −397.8 | |

| LS,s | 780 | 2.90 | −245.4± 1.8 | 61.5 | −76.3 | −134.6 | −0.1 | −394.9 | ||

| LS,m | 1095 | 3.25 | −252.6± 1.6 | 56.0 | −76.5 | −120.5 | −0.1 | −393.7 | ||

| LS,l | 1785 | 3.81 | −261.2± 1.9 | 48.6 | −77.2 | −102.9 | −0.1 | −392.8 | ||

| BM,m | 1095 | 3.25 | −248.9± 0.4 | 70.8 | −68.3 | −145.1 | −0.3 | −391.8 | ||

| BM,l | 1785 | 3.81 | −248.7± 0.4 | 69.8 | −67.7 | −145.1 | −0.3 | −392.0 | ||

| Water | LS,ss | 533 | 2.54 | −172.6± 0.5 | −75.8 | −77.8 | 0.0 | −0.2 | −326.4 | |

| LS,s | 800 | 2.90 | −181.8± 0.5 | −66.7 | −78.3 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −326.9 | ||

| LS,m | 1091 | 3.21 | −188.1± 0.5 | −60.4 | −78.4 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −327.0 | ||

| LS,l | 1827 | 3.80 | −197.8± 0.5 | −51.3 | −79.2 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −328.4 | ||

| BM,m | 1091 | 3.21 | −173.7± 0.5 | −77.4 | −76.6 | 0.0 | −0.3 | −328.0 | ||

| BM,l | 1827 | 3.80 | −175.5± 0.5 | −75.7 | −79.2 | 0.0 | −0.3 | −330.7 | ||

| ACE | CAPO | LS,ss | 468 | 2.46 | −74.5± 0.2 | −70.8 | 75.4 | 0.0 | −0.3 | −70.2 |

| LS,s | 780 | 2.90 | −84.5± 0.2 | −62.1 | 76.3 | 0.0 | −0.2 | −70.5 | ||

| LS,m | 1095 | 3.24 | −90.8± 0.3 | −56.5 | 76.8 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −70.6 | ||

| LS,l | 1792 | 3.81 | −99.1± 0.3 | −49.0 | 77.1 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −71.1 | ||

| BM,m | 1095 | 3.24 | −65.9± 0.3 | −71.7 | 68.4 | 0.0 | −0.4 | −69.6 | ||

| BM,l | 1792 | 3.81 | −66.2± 0.3 | −70.7 | 67.4 | 0.0 | −0.4 | −69.9 | ||

| CHB | LS,ss | 471 | 2.46 | −117.8± 0.5 | −70.2 | 75.4 | −0.2 | −0.3 | −113.1 | |

| LS,s | 780 | 2.90 | −128.0± 0.6 | −61.7 | 76.3 | −0.1 | −0.2 | −113.7 | ||

| LS,m | 1090 | 3.24 | −134.1± 0.6 | −56.3 | 76.9 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −113.7 | ||

| LS,l | 1784 | 3.81 | −142.7± 0.6 | −48.8 | 77.2 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −114.5 | ||

| BM,m | 1090 | 3.24 | −109.5± 0.4 | −71.0 | 68.5 | −0.3 | −0.3 | −112.6 | ||

| BM,l | 1784 | 3.81 | −110.0± 0.4 | −70.0 | 67.6 | −0.3 | −0.3 | −113.0 | ||

| CPOS | LS,ss | 474 | 2.47 | −288.7± 0.3 | 70.0 | 75.5 | −157.6 | −0.3 | −301.1 | |

| LS,s | 780 | 2.90 | −301.9± 0.3 | 61.6 | 76.3 | −134.5 | −0.2 | −298.7 | ||

| LS,m | 1095 | 3.24 | −310.1± 0.3 | 56.1 | 76.5 | −120.5 | −0.1 | −298.1 | ||

| LS,l | 1781 | 3.80 | −319.8± 0.3 | 48.8 | 77.3 | −103.0 | −0.1 | −296.8 | ||

| BM,m | 1095 | 3.24 | −290.5± 0.3 | 70.8 | 68.3 | −144.8 | −0.3 | −296.5 | ||

| BM,l | 1781 | 3.80 | −289.3± 0.3 | 69.8 | 67.9 | −144.9 | −0.3 | −296.8 | ||

| CNEG | LS,ss | 479 | 2.47 | 37.5± 0.4 | −208.9 | 75.5 | 155.8 | −0.3 | 59.5 | |

| LS,s | 780 | 2.90 | 30.2± 0.4 | −184.6 | 76.3 | 133.7 | −0.2 | 55.4 | ||

| LS,m | 1095 | 3.24 | 25.0± 0.4 | −168.2 | 76.7 | 120.0 | −0.1 | 53.4 | ||

| LS,l | 1788 | 3.81 | 18.0± 0.4 | −146.1 | 77.2 | 102.5 | −0.1 | 51.5 | ||

| BM,m | 1095 | 3.24 | 55.4± 0.4 | −212.9 | 68.4 | 143.2 | −0.3 | 53.8 | ||

| BM,l | 1788 | 3.81 | 53.3± 0.4 | −210.1 | 67.7 | 143.2 | −0.3 | 53.8 | ||

| Water | LS,ss | 526 | 2.53 | −300.8± 0.6 | −76.0 | 77.6 | 0.0 | −0.3 | −299.5 | |

| LS,s | 800 | 2.90 | −310.6± 0.7 | −66.6 | 78.3 | 0.0 | −0.2 | −299.1 | ||

| LS,m | 1132 | 3.25 | −318.6± 0.7 | −59.7 | 78.9 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −299.5 | ||

| LS,l | 1826 | 3.81 | −327.0± 0.7 | −51.2 | 79.1 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −299.2 | ||

| BM,m | 1132 | 3.25 | −299.8± 0.6 | −77.2 | 77.0 | 0.0 | −0.3 | −300.3 | ||

| BM,l | 1826 | 3.81 | −301.5± 0.6 | −75.6 | 79.0 | 0.0 | −0.3 | −298.4 |

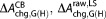

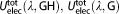

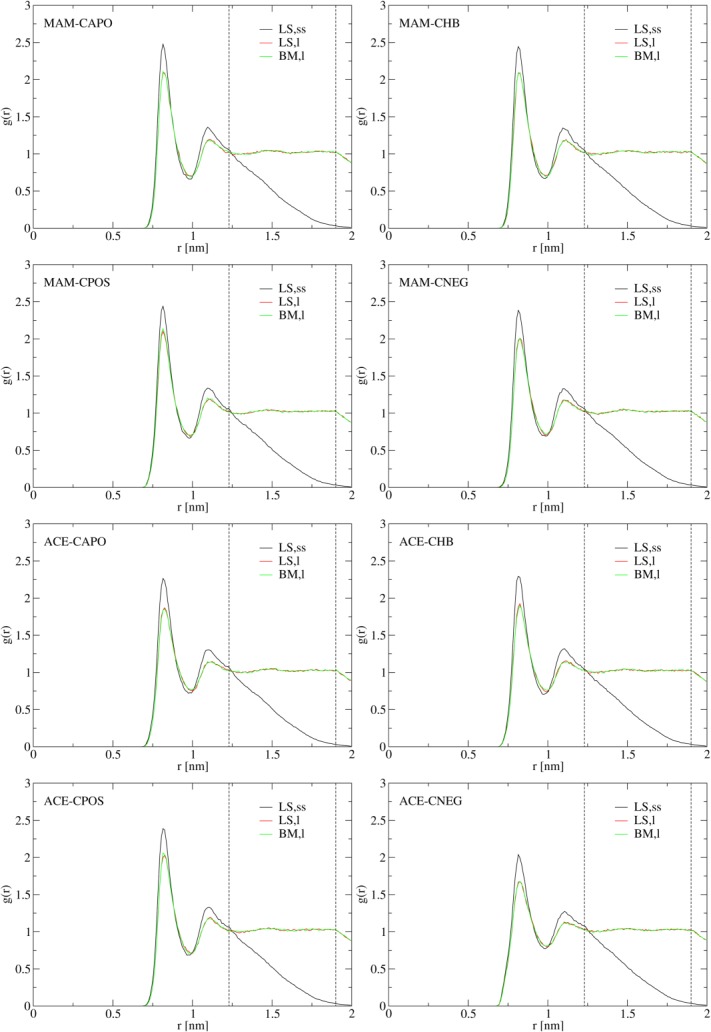

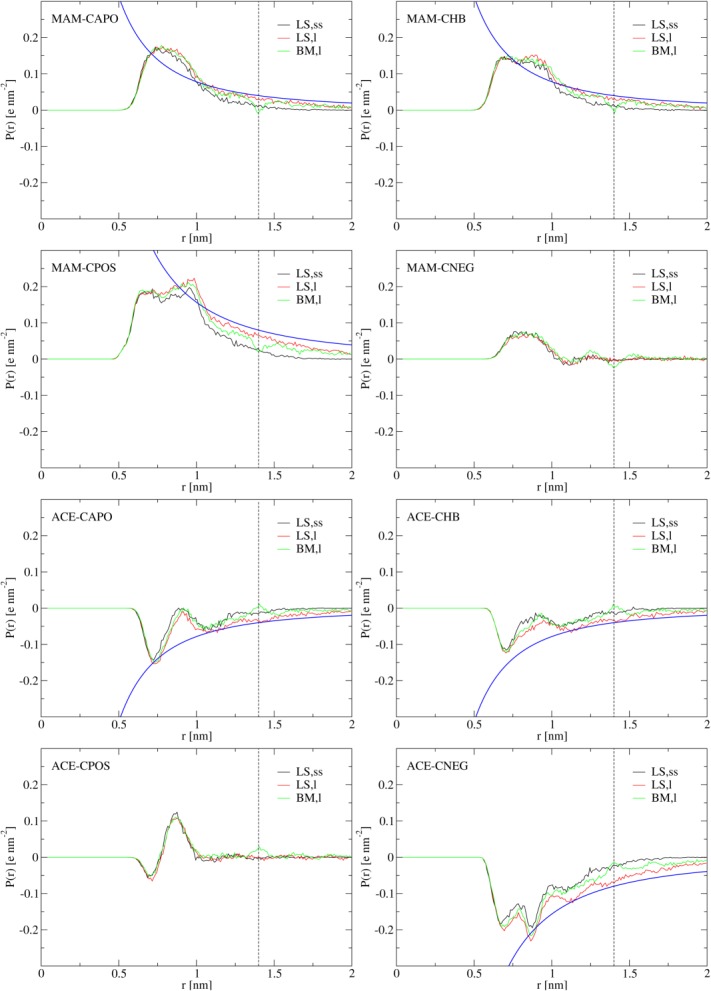

For all guest-host complexes, in simulations LS,ss, g(r) shows spurious density fluctuations (overestimated height of the first and second peaks; Fig. 3) and P(r) shows marked underpolarization in comparison to the Born polarization (due to the large influence of periodic solute copies, a consequence of the small edge length of the computational box; Fig. 4). As discussed in Appendix section “Calculation of

(due to the large influence of periodic solute copies, a consequence of the small edge length of the computational box; Fig. 4). As discussed in Appendix section “Calculation of ”, the former artifact might cause the

”, the former artifact might cause the correction [eq. (14)] to be inadequate. The long-range regime of the latter artifact is corrected by the

correction [eq. (14)] to be inadequate. The long-range regime of the latter artifact is corrected by the correction [eqs. (10) and (11)]. However, short-range artifacts in the solvent polarization, which affect solvation shell structure in the vicinity of the guest-host complex, cannot be represented by a continuum-electrostatics description of the solvent and are thus not captured by the

correction [eqs. (10) and (11)]. However, short-range artifacts in the solvent polarization, which affect solvation shell structure in the vicinity of the guest-host complex, cannot be represented by a continuum-electrostatics description of the solvent and are thus not captured by the correction [eqs. (10) and (11)]. Such artifacts appear especially pronounced in simulation LS,ss of complexes MAM-CNEG and ACE-CNEG. This is evidenced by the relatively large deviation of the short-range P(r) in simulation LS,ss from the corresponding polarization in simulations LS,l and BM,l in the fully-charged complex ACE-CNEG (Fig. 4) and in complex MAM-CNEG containing the uncharged guest molecule (data not shown). Note furthermore that in simulations BM,m and BM,l, P(r) shows marked cutoff artifacts at the cutoff distance of 1.4 nm (a dip in the case of MAM-containing complexes and a crest in the case of ACE-containing complexes) and just before the cutoff distance (overpolarization in the case of MAM-containing complexes). These peculiarities, arising from molecule-based cutoff truncation in an explicit-solvent system, are also not captured by the continuum-electrostatics analog of P(r) for the BM scheme94,97 and can thus not be remedied by

correction [eqs. (10) and (11)]. Such artifacts appear especially pronounced in simulation LS,ss of complexes MAM-CNEG and ACE-CNEG. This is evidenced by the relatively large deviation of the short-range P(r) in simulation LS,ss from the corresponding polarization in simulations LS,l and BM,l in the fully-charged complex ACE-CNEG (Fig. 4) and in complex MAM-CNEG containing the uncharged guest molecule (data not shown). Note furthermore that in simulations BM,m and BM,l, P(r) shows marked cutoff artifacts at the cutoff distance of 1.4 nm (a dip in the case of MAM-containing complexes and a crest in the case of ACE-containing complexes) and just before the cutoff distance (overpolarization in the case of MAM-containing complexes). These peculiarities, arising from molecule-based cutoff truncation in an explicit-solvent system, are also not captured by the continuum-electrostatics analog of P(r) for the BM scheme94,97 and can thus not be remedied by .

.

Figure 3.

Radial distribution g(r) [eq. (2)] of water oxygen atoms around the center of mass of the 60 buckyball carbon atoms, evaluated from simulations LS,ss, LS,l, and BM,l for systems containing guest molecules MAM or ACE in hydrated host molecules CAPO, CHB, CPOS, or CNEG. The vertical dashed lines indicate and

and , that is, the threshold beyond which g(r) decays due to box-corner artifacts.

, that is, the threshold beyond which g(r) decays due to box-corner artifacts.

Figure 4.

Radial polarization P(r) [eq.(3)] of water molecules around the MAM nitrogen atom or the ACE carboxylate carbon atom in hydrated host molecules CAPO, CHB, CPOS, or CNEG, evaluated from simulations LS,ss, LS,l, and BM,l. The blue line depicted for systems MAM-CAPO, MAM-CHB, MAM-CPOS, ACE-CAPO, ACE-CHB, and ACE-CNEG is the Born polarization [eq. (6)] according to a system where the total solute (guest and host) charge is centered at the MAM nitrogen or the ACE carboxylate carbon atom. The vertical dashed line indicates the cutoff distance

[eq. (6)] according to a system where the total solute (guest and host) charge is centered at the MAM nitrogen or the ACE carboxylate carbon atom. The vertical dashed line indicates the cutoff distance nm used in simulations BM,l.

nm used in simulations BM,l.

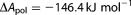

For the systems considered in the present study, the magnitude of correction terms , and

, and (CPOS and CNEG only) is very large (on the order of 50–200 kJ mol−1). For hydration in pure water,

(CPOS and CNEG only) is very large (on the order of 50–200 kJ mol−1). For hydration in pure water, is always negative (independent of the sign of the guest charge) to account for the underhydration of the guest molecule caused by the presence of neighboring periodic copies (LS scheme), or the omission of guest-solvent interactions outside the cutoff sphere (BM scheme). In contrast,

is always negative (independent of the sign of the guest charge) to account for the underhydration of the guest molecule caused by the presence of neighboring periodic copies (LS scheme), or the omission of guest-solvent interactions outside the cutoff sphere (BM scheme). In contrast, is positive for MAM-charging in CNEG and ACE-charging in CPOS because in these complexes the initial state of the TI procedure contains a charged guest-host complex, whereas the final state contains a neutral complex, that is, the electrostatic potential sampled at the guest atom sites is spurious in the initial rather than in the final state. As is the case for hydration in pure water,

is positive for MAM-charging in CNEG and ACE-charging in CPOS because in these complexes the initial state of the TI procedure contains a charged guest-host complex, whereas the final state contains a neutral complex, that is, the electrostatic potential sampled at the guest atom sites is spurious in the initial rather than in the final state. As is the case for hydration in pure water, is negative for the charging of cations (MAM) and positive for the charging of anions (ACE). Because of the absence of electrostatic guest-host interactions,

is negative for the charging of cations (MAM) and positive for the charging of anions (ACE). Because of the absence of electrostatic guest-host interactions, is zero for the charging in CAPO. As the LS and BM electrostatic interaction functions used in the present study are reduced in comparison to the Coulombic component (presence of self- and reaction-field terms71,86),

is zero for the charging in CAPO. As the LS and BM electrostatic interaction functions used in the present study are reduced in comparison to the Coulombic component (presence of self- and reaction-field terms71,86), is negative for charging of MAM in CHB and the oppositely-charged CNEG and of ACE in CHB and the oppositely-charged CPOS. Likewise, it is positive for charging of the guests in the like-charged hosts, that is, MAM in CPOS and ACE in CNEG. In comparison to the other correction terms,

is negative for charging of MAM in CHB and the oppositely-charged CNEG and of ACE in CHB and the oppositely-charged CPOS. Likewise, it is positive for charging of the guests in the like-charged hosts, that is, MAM in CPOS and ACE in CNEG. In comparison to the other correction terms, is of rather small magnitude (0.1–0.4 kJ mol−1), because it is a short-range electrostatic interaction reduced by the short-range singularity associated with the Coulombic component. For the LS scheme, the magnitude of

is of rather small magnitude (0.1–0.4 kJ mol−1), because it is a short-range electrostatic interaction reduced by the short-range singularity associated with the Coulombic component. For the LS scheme, the magnitude of decreases with increasing box-edge length due to decreasing periodicity artifacts. For the BM scheme,

decreases with increasing box-edge length due to decreasing periodicity artifacts. For the BM scheme, is independent of box-edge length.

is independent of box-edge length.

Table3 reports raw free energies of charging the guest molecule due to the host and periodic host copies (LS scheme only), [eq. (22)], or due to the solvent and periodic solvent copies (LS scheme only),

[eq. (22)], or due to the solvent and periodic solvent copies (LS scheme only), [eq. (23)], and corresponding corrected values

[eq. (23)], and corresponding corrected values and

and [eqs. (24) and (25)].

[eqs. (24) and (25)]. differs from

differs from in that it is exempt of interaction of the guest with periodic host copies (LS scheme) or of reaction-field terms (BM scheme) and corrected to have Coulombic electrostatic interactions between the guest and the host within the central computational box (

in that it is exempt of interaction of the guest with periodic host copies (LS scheme) or of reaction-field terms (BM scheme) and corrected to have Coulombic electrostatic interactions between the guest and the host within the central computational box ( ; Table2).

; Table2). differs from

differs from in that it is corrected for all solvent-associated artifacts, that is, spurious solvent polarization and wrong dielectric permittivity of the solvent model, improper electrostatic potential summation and the presence of electrostatic interactions between excluded atoms (

in that it is corrected for all solvent-associated artifacts, that is, spurious solvent polarization and wrong dielectric permittivity of the solvent model, improper electrostatic potential summation and the presence of electrostatic interactions between excluded atoms ( ; Table2). It can be seen that application of the correction terms may cause considerable shifts in the ratio of

; Table2). It can be seen that application of the correction terms may cause considerable shifts in the ratio of and

and . In particular, the relative dominance of the components reverses in the case of MAM-CHB and MAM-CPOS, that is, while interactions with the host dominate

. In particular, the relative dominance of the components reverses in the case of MAM-CHB and MAM-CPOS, that is, while interactions with the host dominate , those with the solvent dominate

, those with the solvent dominate (Table3). Moreover, in the case of ACE-CPOS, the signs of

(Table3). Moreover, in the case of ACE-CPOS, the signs of and

and are different for simulations LS,ss, LS,s, LS,m, BM,m, and BM,l. Corresponding uncorrected values are slightly negative, that is, indicative of favorable ACE-solvent interactions, whereas the corrected values are positive, indicative of a solvent polarization unfavorable for interactions with an anion (solvent polarized by the positively-charged functional group in CPOS, which is located closer to the solvent than is the ACE ion). For complexes MAM-CNEG, ACE-CPOS, and ACE-CNEG, the raw and corrected free energies of charging due to the host molecule,

are different for simulations LS,ss, LS,s, LS,m, BM,m, and BM,l. Corresponding uncorrected values are slightly negative, that is, indicative of favorable ACE-solvent interactions, whereas the corrected values are positive, indicative of a solvent polarization unfavorable for interactions with an anion (solvent polarized by the positively-charged functional group in CPOS, which is located closer to the solvent than is the ACE ion). For complexes MAM-CNEG, ACE-CPOS, and ACE-CNEG, the raw and corrected free energies of charging due to the host molecule, and

and , are the dominant components in the charging contributions to the respective binding free energies

, are the dominant components in the charging contributions to the respective binding free energies and

and , whereas for complex ACE-CHB the charging contributions

, whereas for complex ACE-CHB the charging contributions and

and due to the solvent are dominant.

due to the solvent are dominant.

Table 3.

Charging free-energy contributions due to the solvent,  [eq. (25)], and due the host molecule,

[eq. (25)], and due the host molecule, [eq. (24)], of the guest molecules MAM and ACE in hydrated host molecules CAPO, CHB, CPOS, and CNEG (section “MD simulations”). Values obtained with the LS scheme in boxes of edge lengths

[eq. (24)], of the guest molecules MAM and ACE in hydrated host molecules CAPO, CHB, CPOS, and CNEG (section “MD simulations”). Values obtained with the LS scheme in boxes of edge lengths , and Ll are labeled LS,ss, LS,s, LS,m, and LS,l, respectively, and values obtained with the BM scheme in boxes of edge lengths Lm and Ll are labeled BM,m and BM,l, respectively (section “Simulated guest-host systems”). The charging free energies

, and Ll are labeled LS,ss, LS,s, LS,m, and LS,l, respectively, and values obtained with the BM scheme in boxes of edge lengths Lm and Ll are labeled BM,m and BM,l, respectively (section “Simulated guest-host systems”). The charging free energies and

and are calculated as the sum of the raw charging free energy

are calculated as the sum of the raw charging free energy [eq. (23)] and the correction terms

[eq. (23)] and the correction terms , and

, and [eqs. (10), (11), (14), (15), and (18)] and as the sum of the raw charging free energy

[eqs. (10), (11), (14), (15), and (18)] and as the sum of the raw charging free energy [eq. (22)] and the correction term

[eq. (22)] and the correction term [eqs. (16) and (17)], respectively (section “Solute and solvent contributions to the free energy of charging”).

[eqs. (16) and (17)], respectively (section “Solute and solvent contributions to the free energy of charging”).

| Guest | Host | Scheme |

(kJ mol−1) (kJ mol−1) |

(kJ mol−1) (kJ mol−1) |

(kJ mol−1) (kJ mol−1) |

(kJ mol−1) (kJ mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAM | CAPO | LS,ss | −4.4 | 0.0 | −151.2 | 0.0 |

| LS,s | −12.4 | 0.0 | −151.2 | 0.0 | ||

| LS,m | −17.6 | 0.0 | −151.4 | 0.0 | ||

| LS,l | −24.7 | 0.0 | −151.1 | 0.0 | ||

| BM,m | −8.5 | 0.0 | −150.0 | 0.0 | ||

| BM,l | −9.7 | 0.0 | −149.1 | 0.0 | ||

| CHB | LS,ss | −1.8 | −36.9 | −147.9 | −37.6 | |

| LS,s | −9.9 | −37.4 | −148.1 | −37.8 | ||

| LS,m | −15.0 | −38.2 | −148.5 | −38.5 | ||