Abstract

Polyglutamine repeat expansion in ataxin-3 causes neurodegeneration in the most common dominant ataxia, Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 3 (SCA3). Since reducing levels of disease proteins improves pathology in animals, we investigated how ataxin-3 is degraded. Here we show that, unlike most proteins, ataxin-3 turnover does not require its ubiquitination, but is regulated by Ubiquitin-Binding Site 2 (UbS2) on its N terminus. Mutating UbS2 decreases ataxin-3 protein levels in cultured mammalian cells and in Drosophila melanogaster by increasing its proteasomal turnover. Ataxin-3 interacts with the proteasome-associated proteins Rad23A/B through UbS2. Knockdown of Rad23 in cultured cells and in Drosophila results in lower levels of ataxin-3 protein. Importantly, reducing Rad23 suppresses ataxin-3-dependent degeneration in flies. We present a mechanism for ubiquitination-independent degradation that is impeded by protein interactions with proteasome-associated factors. We conclude that UbS2 is a potential target through which to enhance ataxin-3 degradation for SCA3 therapy.

Keywords: Deubiquitinase, Drosophila, Neurodegeneration, Neuroprotection, Polyglutamine, Proteasome, hHR23, Spinocerebellar Ataxia, Ubiquitin

INTRODUCTION

Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 3 (SCA3), which is also known as Machado-Joseph Disease, is an age-related neurodegenerative disease that belongs to the family of polyglutamine (polyQ)-dependent disorders1, 2. The maladies that comprise this group result from abnormal expansions in the polyQ region of different proteins. PolyQ diseases also include Huntington's, Spinobulbar Muscular Atrophy, Dentatorubral-Pallidoluysian Atrophy and five more SCAs2, 3, 4.

SCA3, considered to be the most common dominantly inherited ataxia in the world, is caused by an abnormal CAG expansion in the ATXN3 gene that is normally 12–42 repeats in length, but is expanded to ~52–84 repeats in diseased individuals1. PolyQ expansion occurs in the protein ataxin-3, a deubiquitinase (DUB) that is involved in protein quality control. Ataxin-3 protects mammalian cells against various forms of stress5 and serves a protective role against toxic polyQ proteins in Drosophila6, 7. How pathogenic expansion of the polyQ region of ataxin-3 causes SCA3 is unknown. There is presently no cure for this disease.

Reducing the levels of disease proteins improves degeneration in various animal models of proteinopathies, including polyQ diseases3, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17. Consequently, a potential therapeutic strategy for SCA3 entails reducing the levels of the ataxin-3 protein. This concept is supported by recent work that used viral-mediated delivery of RNA-interference (RNAi) constructs to reduce levels of ataxin-3 protein in mouse brain18, and alleviated SCA3-like pathology in one study19.

The mechanism of degradation of the ataxin-3 protein is not clear1. Most cellular proteins are degraded by being post-translationally modified with the small protein ubiquitin, which targets them for proteasomal degradation20. Here, we present evidence that ubiquitination of ataxin-3 is not necessary for its proteasomal degradation, and find that the turnover of this polyQ protein is regulated by Ubiquitin-Binding Site 2 (UbS2) on its N terminus. UbS2 mediates the interaction of ataxin-3 with the proteasome-associated proteins Rad23A and Rad23B21, 22, 23, 24. According to our studies, this interaction prevents the proteasomal turnover of ataxin-3. Our findings describe a precise molecular target through which to enhance the degradation of ataxin-3 protein for SCA3 therapeutics, perhaps by designing molecules that bind UbS2 and prevent its interaction with Rad23A/B.

RESULTS

Ataxin-3 does not require ubiquitination to be degraded

Previous reports presented evidence that the turnover of normal and pathogenic ataxin-3 (figure 1A) depends on the proteasome1, and we showed that ataxin-3 protein is ubiquitinated in mammalian cells, in mouse brain and in Drosophila7, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29. Based on these observations, one would expect ataxin-3 to be degraded by becoming ubiquitinated and thus targeted for the proteasome. Yet, while the role of the proteasome in ataxin-3 degradation is well supported1, it is not entirely clear that ataxin-3 needs be ubiquitinated in order to be degraded.

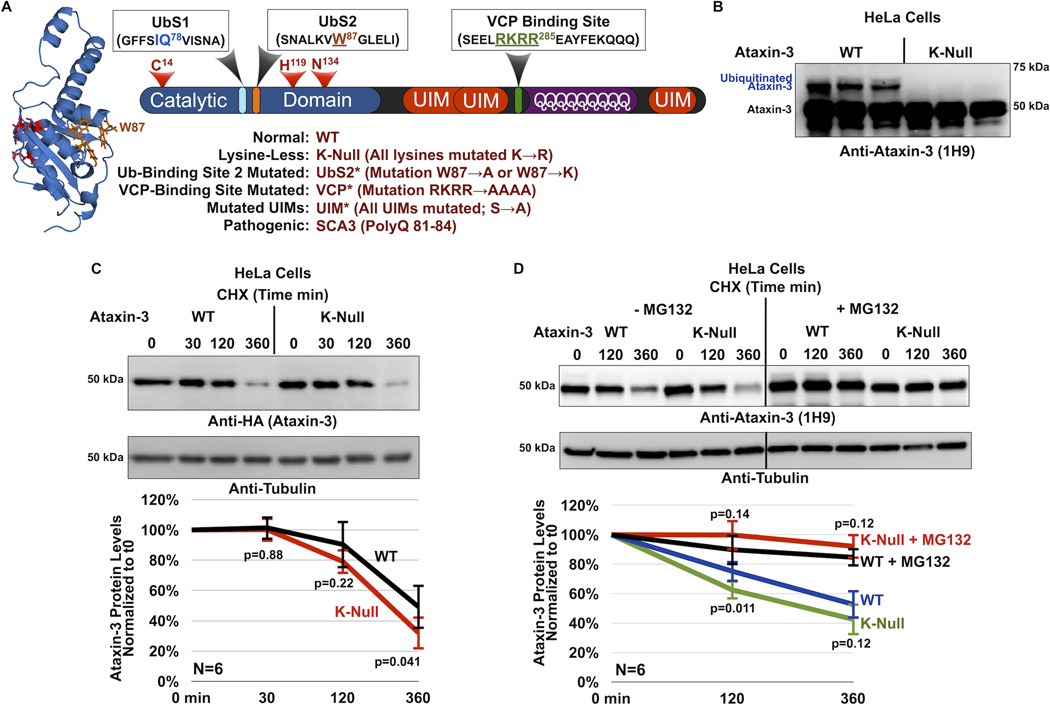

Figure 1. Cellular degradation of ataxin-3 does not require its own ubiquitination.

A) Schematic of ataxin-3. The catalytic triad (red) and two ubiquitin-binding sites (UbS1, light blue and UbS2, orange) are on the catalytic domain (blue). Next are three ubiquitin-interacting motifs (UIMs; red), separated by the polyglutamine (polyQ) region. Preceding the polyQ is the VCP-binding site (green). The NMR-based structure of the catalytic domain of ataxin-3 was reported in ref. [22]. The file for the structure depicted here was obtained from NCBI (PDB: 1YZB) and was rendered and annotated using the software application MacPyMOL. Legend: abbreviations used in this report.

B) Western blot of whole cell lysates. HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated constructs and treated with MG132 (6 hours, 15µM) 24 hours post transfection to enhance the capture of ataxin-3 ubiquitination, as we have described before26, 27. We previously showed through stringent immunopurification protocols and mass spectrometry that the more slowly migrating band of ataxin-3 is ubiquitinated ataxin-325, 26, 27, 28, 54. Equal total protein loaded (50µg/lane). Transfections were performed independently in triplicate. Overexposed blot to highlight ubiquitinated ataxin-3.

C) Top: Western blots of whole cell lysates. HeLa cells were transfected as indicated and treated for the specified amounts of time with cycloheximide (CHX) 48 hours post-transfection. Bottom: Means of ataxin-3 signal quantified from blots on the top and other similar experiments. P values are from Student T-tests comparing protein levels of K-Null ataxin-3 to the wild type counterpart. Error bars: standard deviations. N=6 independently conducted experiments.

D) Top: Western blots of whole cell lysates of HeLa cells transfected as indicated, treated or not for 2 hours with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (10µM) 24 hours after transfection, then treated for the specified amounts of time with cycloheximide (CHX). Bottom: Means of ataxin-3 signal quantified from western blots on the top and other similar, independent experiments. P values are from Student T-tests comparing protein levels of K-Null ataxin-3 to the normal version of the protein. Error bars: standard deviations. N=6 independently conducted experiments.

To examine this possibility, we used a version of ataxin-3 whose lysine residues are mutated into the similar but non-ubiquitinatable amino acid arginine (K-Null). We do not detect ubiquitinated species with K-Null ataxin-3 in cultured mammalian cells (figure 1B) or in Drosophila (figure 2B, as well as other supportive data published by us7, 27). Mutating all of the fifteen lysine residues of ataxin-3 into arginines does not affect its subcellular localization in mammalian cells, or disrupt its ability to cleave ubiquitin chains in reconstituted systems in vitro27. Lysine-less ataxin-3 retains some of its functions: similarly to the wild type version of this DUB, the K-null variant is able to somewhat suppress neurodegeneration in Drosophila, although this function cannot be enhanced by its own ubiquitination in order to reach the full protective effect of ubiquitinatable ataxin-37.

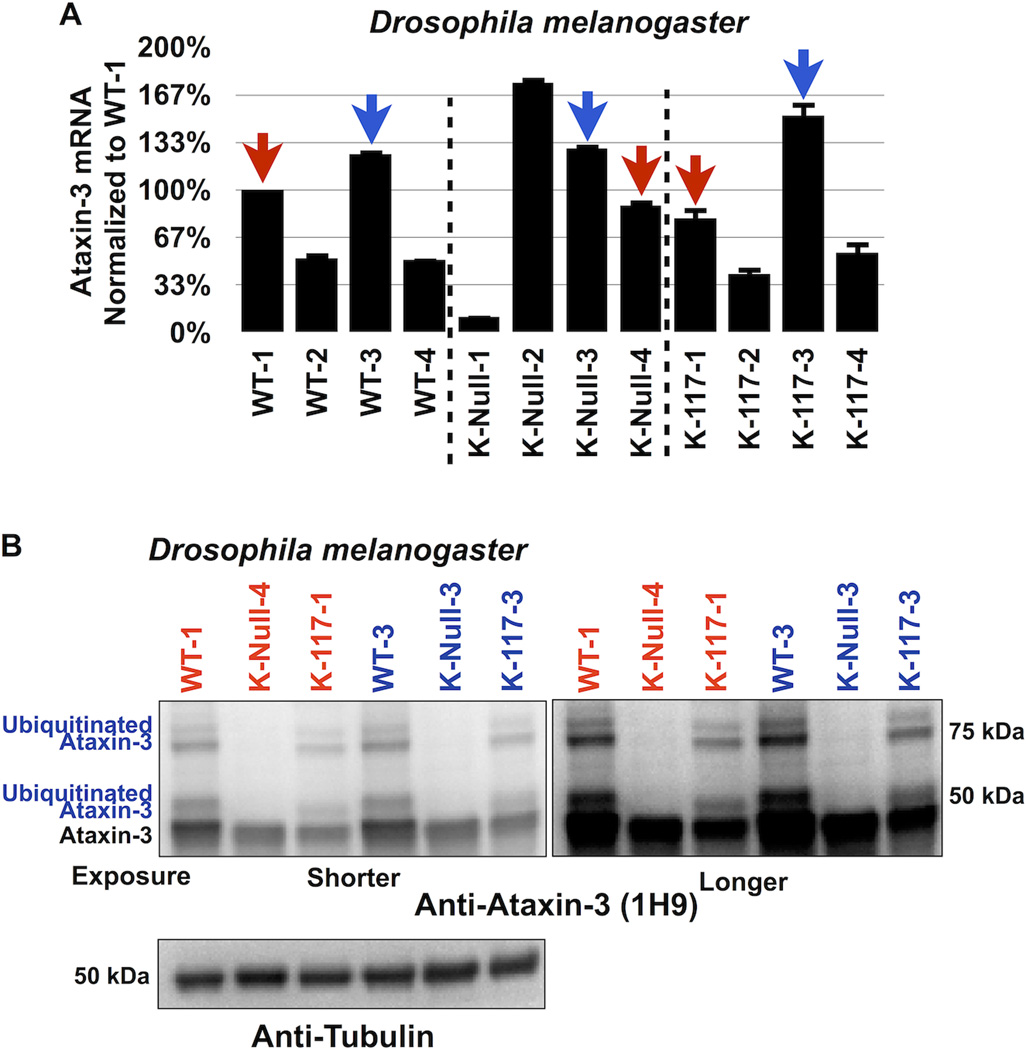

Figure 2. Lysine-less ataxin-3 does not accumulate in vivo in Drosophila.

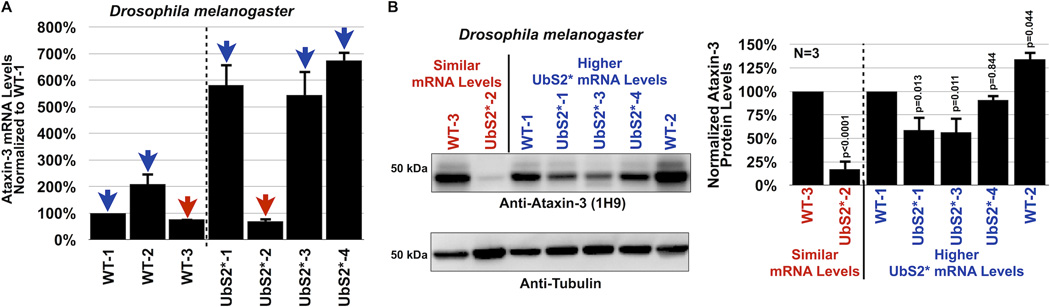

A) Selection of transgenic fly lines that express similar levels of ataxin-3 variants. Quantitative RT-PCR results from whole flies expressing the versions of UAS-ataxin-3 noted in the panel. At least 5 flies were used per genotype per experiment. Driver was sqh-Gal4 (ubiquitous expression31, 32). All flies were heterozygous for UAS-ataxin-3 and sqh-Gal4 transgenes. Red and blue arrows: lines that we chose for western blotting shown in panel B. Experiment performed independently in triplicate. Shown are mean ataxin-3 mRNA levels normalized to WT-1. Error bars: standard deviations. Flies were 1–3 days old.

B) Western blots from whole fly lysates expressing the indicated UAS-ataxin-3 constructs based on qRT-PCR data from panel A. Driver was sqh-Gal4. All flies were heterozygous for UAS-ataxin-3 and sqh-Gal4 transgenes, as in panel A. Ten or more flies per genotype were homogenized. Blots are representative of experiment performed independently in triplicate, with similar results. Flies were 1–3 days old.

We first examined the turnover of K-Null ataxin-3 protein compared to its wild type counterpart in cultured cells. Figure 1C summarizes cycloheximide (CHX)-based pulse-chase studies, where we observe that the turnover of K-Null ataxin-3 is not slower than that of WT ataxin-3. In fact, based on quantification of data from multiple western blots, K-Null ataxin-3 might be degraded slightly more quickly than the normal version of this DUB in cells (figure 1C, 360 min time point; 1D, 120 min time point). Both WT and K-Null ataxin-3 proteins are stabilized in cells by the addition of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Figure 1D), a finding that is in accordance with previous reports that ataxin-3 turnover in cells is proteasome-dependent1, 25.

Subsequently, we used the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster to investigate whether K-Null ataxin-3 accumulates in vivo in an intact organism. We utilized the Gal4-UAS system30 to express ataxin-3 constructs throughout the fly7. We generated flies that express WT, K-Null or K-117 (the lysine predominantly ubiquitinated in vitro and in mammalian cell culture27) ataxin-3 by using the ubiquitous Gal4 driver sqh-Gal431, 32. We compared fly lines that express the various ataxin-3 transgenes at similar mRNA levels, according to quantitative RT-PCR (figure 2A). As shown in figure 2B, K-Null ataxin-3 protein does not accumulate compared to WT or K-117 ataxin-3. Together, results in figures 1 and 2 lead us to conclude that ubiquitination of ataxin-3 is not absolutely necessary for its degradation.

UbS2 regulates ataxin-3 protein levels and turnover in cells

Since ubiquitination of ataxin-3 does not appear to be necessary for its turnover (figures 1 and 2), we wondered whether protein-binding domains of this DUB are involved in its degradation. Several domains on ataxin-3 enable its direct interaction with other proteins (figure 1A). Starting at the N-terminus, first is UbS1 on the catalytic domain. UbS1 binds ubiquitin and is necessary for the catalytic activity of ataxin-323. Next is UbS2, which binds ubiquitin as well as Rad23A and Rad23B21, 23. Rad23A/B facilitate substrate protein degradation by reversibly associating with the proteasome33, 34. Previous structural work focusing on the catalytic domain of ataxin-3 indicated that mutating the amino acid tryptophan (W) at position 87 disrupts the ability of UbS2 to interact with the isolated ubiquitin-like domain of Rad2321, 23. Through an in vitro pulldown assay that utilized recombinant, full-length ataxin-3 and Rad23A, we confirmed that mutating W87 into an alanine residue diminishes the ability of these two proteins to interact (supplementary figure 1A). We also verified in mammalian cell culture that this mutation reduces the capacity of an otherwise normal, full-length ataxin-3 to co-immunoprecipitate endogenous Rad23A and Rad23B (supplementary figure 1B). Mutating UbS2 does not abrogate the catalytic activity of ataxin-323 or affect its subcellular localization (supplementary figure 2). In the C-terminal half of ataxin-3 are three ubiquitin-interacting motifs (UIMs), which bind ubiquitin chains at least four moieties long29. The C-terminal portion also contains an arginine-rich region that binds the AAA ATPase protein VCP (also known as p97)35, 36, 37. VCP functions at least in part as a proteasomal shuttle protein33. Mutating one or more of the arginine residues of the VCP-binding site of full-length ataxin-3 into histidines or alanines has been demonstrated to disrupt its interaction with VCP in reconstituted systems in vitro and in mammalian cells35, 36, 37.

Because ataxin-3 binds to proteins that associate with the proteasome, we examined whether UbS2 or the VCP-binding site regulates its stability. For the experiments described in figure 3A–3F, we utilized ataxin-3 constructs that do not contain lysine residues in order to eliminate any potentially confounding effects from ubiquitination at this stage of our study.

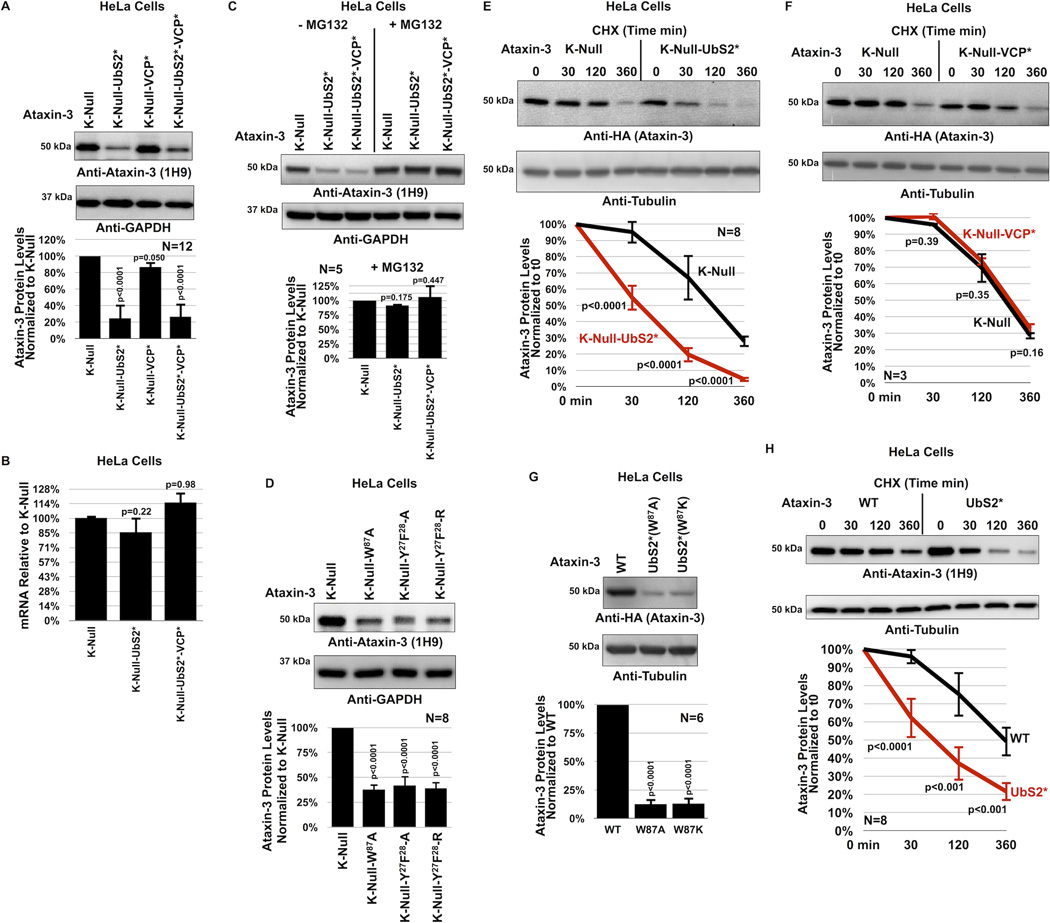

Figure 3. UbS2 of ataxin-3 regulates its degradation in cells.

A) Top: Western blots of whole cell lysates. HeLa cells were transfected as indicated and harvested 24 hours later. Bottom: Means of ataxin-3 signal quantified from blots on the top and other similar experiments. Error bars: standard deviations.

B) qRT-PCR of HeLa cells expressing the indicated constructs. Endogenous control: GAPDH. N=3 independently conducted experiments. Shown are mean ataxin-3 mRNA levels −/+ standard deviations.

C, D) Top: Western blots of whole cell lysates of HeLa cells transfected as indicated, treated or not with MG132 (4 hours, 15µM) 48 hours later and harvested. Bottom: Means of ataxin-3 signal quantified from blots on the top and other similar experiments. Error bars: standard deviations.

E, F) Top: HeLa cells were transfected as indicated and 24 hours later were treated with CHX for the specified amounts of time. For panel E, to have comparable protein amounts of both ataxin-3 versions at time 0 min, we transfected 3× more K-Null(UbS2*) construct than K-Null, which was supplemented with empty vector to equate total DNA per group. Western blots of whole cell lysates. Bottom: Means of ataxin-3 signal quantified from blots on the top and other independent experiments. Error bars: standard deviations.

G) Top: Western blots of whole cell lysates. Two different mutations were used to disrupt UbS2: W87A and W87K, with similar results. Bottom: Means of ataxin-3 signal quantified from blots on the top and other independent experiments. Error bars: standard deviations.

H) Top: HeLa cells were transfected as indicated and 24 hours later were treated with CHX for the specified time points. 3× more ataxin-3(UbS2*) construct was transfected than ataxin-3(WT) to have comparable protein levels at time 0 min. Bottom: Means of ataxin-3 signal quantified from blots on the top and other independent experiments. Error bars: standard deviations.

For panels A, B, C, D and G, P values are from ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc correction comparing the various versions of ataxin-3 to their panel controls. For panels E, F and H, P values are from Student t-tests. N of independently repeated experiments is specified in panels.

Surprisingly, mutating UbS2 (denoted as UbS2*; mutation is W87A unless noted otherwise) markedly reduces ataxin-3 steady-state protein levels in cultured mammalian cells (figure 3A). Mutating the VCP-binding site (denoted as VCP*) does not consistently alter steady-state protein levels. In most experimental repeats we did not detect a difference in the steady-state levels of K-Null ataxin-3 with the VCP-binding site mutated compared to versions with intact VCP-binding, as shown in figure 3A. There were a few instances where the levels of ataxin-3 with mutated VCP-binding were lower, as summarized by the quantification of multiple blots in figure 3A, but this difference did not reach statistical significance. Mutating both UbS2 and the VCP-binding site has an effect similar to that observed when only UbS2 is mutated (figure 3A). The studies in figure 3A were conducted in HeLa cells. A similar effect is observed in HEK-293 cells (supplementaey figure 3A).

The effect from mutating UbS2 does not result from differences at the mRNA level, as those levels are not significantly different (figure 3B). However, the difference in steady-state levels depends on the proteasome. Inhibiting proteasomal activity with MG132 equalizes the levels of ataxin-3 protein with mutated UbS2 to those of ataxin-3 with intact UbS2 (figure 3C and supplementary figure 3B). Two other amino acid residues important for UbS2 are tyrosine (Y) at position 27 and phenylalanine (F) at position 2821, 22. Mutating those amino acids also leads to reduced steady-state levels of ataxin-3 protein in cultured cells (figure 3D).

Next, we examined the turnover rate of ataxin-3 with intact or mutated UbS2 by using CHX-based pulse-chase assays. As shown in figure 3E, ataxin-3 protein with mutated UbS2 is turned over markedly more rapidly than ataxin-3 with intact UbS2. Mutating only the VCP-binding site does not significantly affect turnover (figure 3F). CHX-based analyses are consistent with steady-state examinations, indicating that UbS2 inhibits ataxin-3 degradation in cells, while VCP-binding does not appear to have a significant effect. Based on these findings, we focus the rest of the studies in this report on UbS2.

As already stated, for experiments in panels 3A–F we used K-Null ataxin-3 that contains intact or mutated UbS2. We next investigated whether the protein levels of ataxin-3 with all of its lysines present are also regulated by UbS2. Mutating UbS2 in an otherwise normal ataxin-3 dramatically reduces its steady-state protein levels (figure 3G) and turnover (figure 3H), similar to what we observed with non-ubiquitinatable ataxin-3. Collectively, these results from mammalian cell culture indicate that UbS2 inhibits the proteasomal turnover of non-pathogenic ataxin-3.

UIMs of ataxin-3 have an opposite effect to UbS2 on turnover

For ataxin-3 to be degraded by the proteasome, it needs to come into contact with this cellular machinery. One possibility through which this interaction could occur would be through ataxin-3 ubiquitination. However, our results argue against ubiquitination being necessary for ataxin-3 degradation (figures 1 and 2). Another mechanism that could bridge ataxin-3 to the proteasome could be the poly-ubiquitin binding UIMs of this polyQ protein, which could bind ubiquitinated proteins targeted for the proteasome.

We mutated a conserved serine residue in each UIM of non-pathogenic ataxin-3 into an alanine, disrupting its interaction with ubiquitin chains26, 29, 38. Results in figure 4 indicate that the UIMs regulate the turnover of ataxin-3. Mutating all three UIMs counteracts the degradative effect of UbS2 mutation both at the steady-state level (figure 4A and supplementary figure 4) and turnover rate (figure 4B). We conclude that the UIMs of ataxin-3 have a positive effect on its cellular turnover.

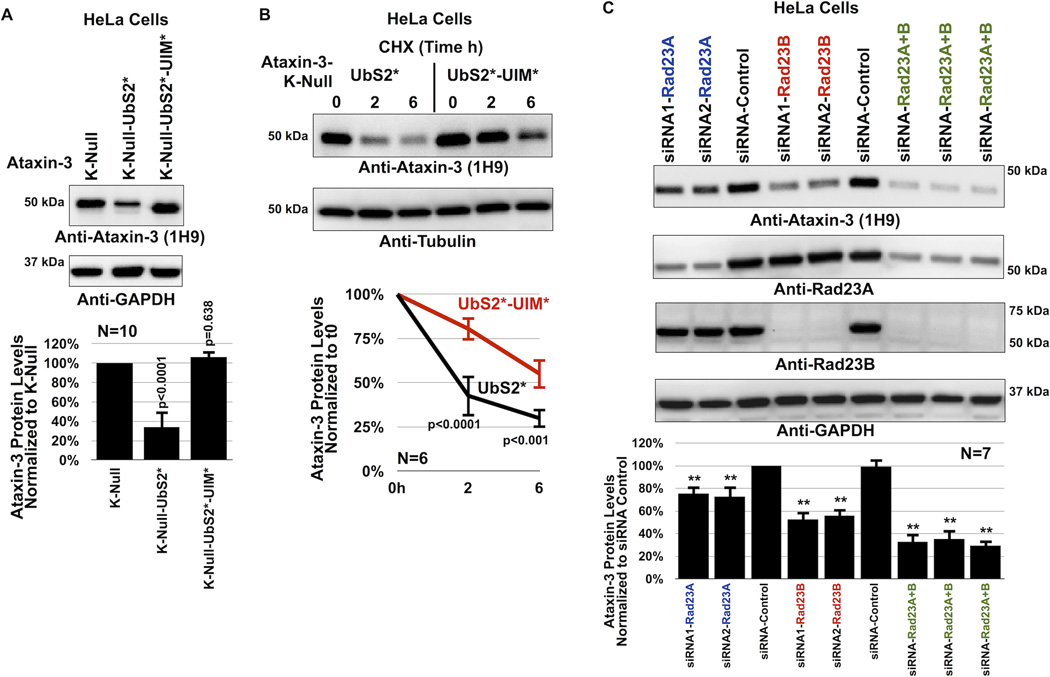

Figure 4. UIMs of ataxin-3 oppose the effect of UbS2 mutation.

A) Top: HeLa cells were transfected as indicated and harvested 48 hours later. Western blots from whole cell lysates. Bottom: Means of ataxin-3 signal quantified from blots on the top and other similar experiments. P values are from ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc correction comparing K-Null ataxin-3 with UbS2 mutated and K-Null ataxin-3 with UbS2 and UIMs mutated to K-Null ataxin-3 with intact domains. Error bars: standard deviations. N=10 independently conducted experiments.

B) Top: HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated constructs. 3× more UbS2* DNA was used than UbS2*-UIM* to begin with approximately the same amount of protein at time 0h. CHX was added to cells 24 hours post transfection for the specified time points. Western blots of whole cell lysates. Bottom: Means of ataxin-3 signal quantified from blots on the top and other similar experiments. P values are from Student T-tests comparing ataxin-3 with UbS2 mutated to ataxin-3 with UbS2 and UIMs mutated. Error bars: standard deviations. N=6 independently conducted experiments.

C) Top: HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated siRNA constructs to knock down endogenous Rad23A, endogenous Rad23B or both, and harvested 48 hours later. Shown are western blots of whole cell lysates. siRNA control: scramble controls. Bottom: Means of ataxin-3 signal quantified from blots on the top and other similar experiments. P values of less than 0.01 are indicated by “**”, and are from ANOVA/Tukey comparing the levels of ataxin-3 protein in RNAi lanes to those in scramble control. Error bars: standard deviations. N=7 independently conducted experiments.

Rad23 regulates ataxin-3 protein levels in mammalian cells

Two proteins that bind ataxin-3 directly at UbS2 are Rad23A and Rad23B21, 23. Therefore, we examined whether Rad23A/B affect ataxin-3 protein levels in cultured cells by using RNA-interference (RNAi). Knockdown of endogenous Rad23A or Rad23B through different, non-overlapping siRNA constructs noticeably decreases levels of Rad23A or Rad23B protein. Their reduction is concomitant with a statistically significant reduction in the levels of endogenous ataxin-3 protein (figure 4C). Simultaneous knockdown of Rad23A and Rad23B has an even stronger effect in reducing normal, endogenous ataxin-3 protein levels (figure 4C). Together, these RNAi-based data are indicative of a protective role from Rad23A and Rad23B on ataxin-3.

UbS2 regulates normal ataxin-3 protein levels in Drosophila

Data in figures 3 and 4 make the case that UbS2 of ataxin-3 is important for its stability in cultured cells. Next, we examined the significance of UbS2 in ataxin-3 protein levels in Drosophila. We generated new transgenic fly lines that express non-pathogenic ataxin-3 with mutated UbS2 and selected lines that express WT and UbS2* ataxin-3 transgenes at similar mRNA levels, as well as ones that express the UbS2* variant more strongly (figure 5A). As shown in figure 5B, the protein levels of UbS2* ataxin-3 are dramatically lower than those of WT ataxin-3 that is expressed similarly at the mRNA level. Even in transgenic lines where the mRNA levels of UbS2* ataxin-3 are approximately 6 fold higher than WT ataxin-3, those protein levels don’t quite approach the levels of normal ataxin-3. These data from an intact organism are consistent with our findings from cultured cells, and collectively support our overall conclusion that UbS2 regulates ataxin-3 protein levels by inhibiting its degradation.

Figure 5. UbS2 mutation leads to reduced ataxin-3 protein levels in Drosophila.

A) Quantitative RT-PCR results from whole flies expressing the noted versions of UAS-ataxin-3 driven by sqh-Gal4. All flies were heterozygous for UAS-ataxin-3 and sqh-Gal4 transgenes. Red arrows: WT and UbS2* lines that have comparable ataxin-3 mRNA levels. Blue arrows: UbS2* lines that have markedly higher ataxin-3 mRNA levels than WT versions. Experiment performed independently in triplicate, utilizing at least 5 flies per genotype per experiment. Shown are mean ataxin-3 mRNA levels normalized to WT-1. Error bars: standard deviations.

B) Left: Western blots from whole flies based on qRT-PCR results from panel A. At least 5 flies were homogenized per genotype. Driver was sqh-Gal4. All flies were heterozygous for UAS-ataxin-3 and sqh-Gal4 transgenes, as in panel A. Note that for this blot 1.5× more lysate was loaded for the line that expresses UbS2*-2 to enable visualization of ataxin-3 protein in this line by western blotting without saturating the signal from other lysates. Right: Means of ataxin-3 signal quantified from blots on the left and other independent experiments. P values are from Student T-test (WT-3 and UbS2*-2) and ANOVA/Tukey (the other lines). Error bars: standard deviations. N=3 independently conducted experiments. Flies were 1–3 days old.

UbS2 and Rad23 regulate pathogenic ataxin-3 in Drosophila

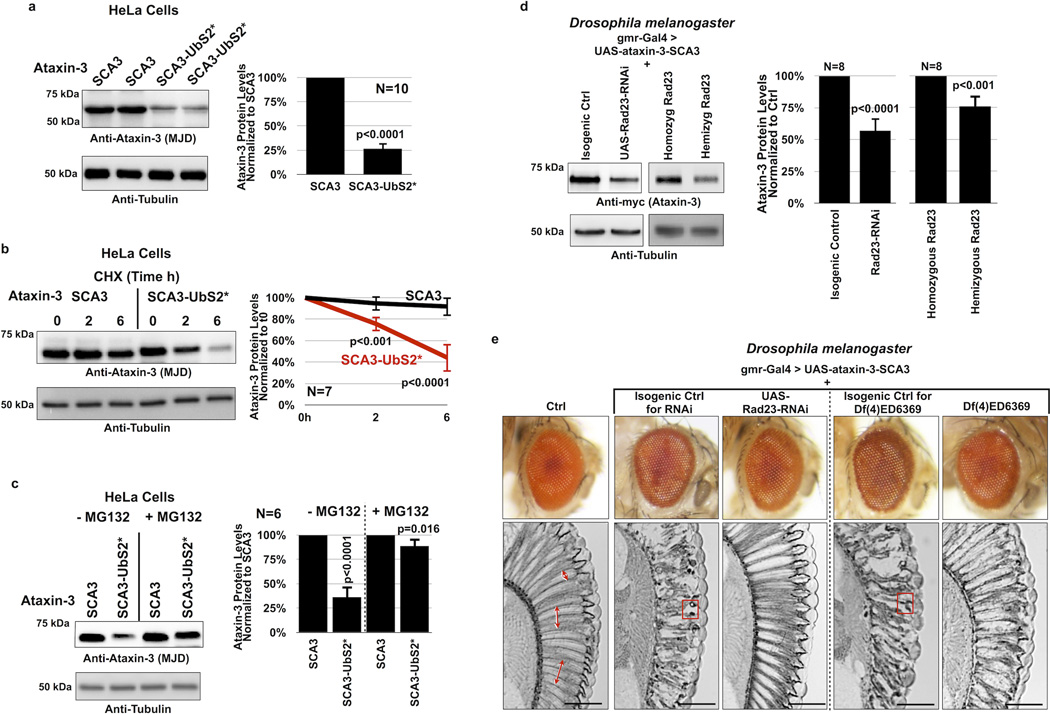

Finally, we examined whether mutating UbS2 on pathogenic ataxin-3 affects its stability (pathogenic variant denoted as SCA3; polyQ length of 81 for the intact version and 84 for UbS2*; these constructs contains all lysine residues). We found that mutating UbS2 of SCA3-causing ataxin-3 reduces its steady-state levels in cultured mammalian cells (figure 6A). Just as we observed with normal ataxin-3, mutating UbS2 enhances the turnover rate of pathogenic ataxin-3 in cells (figure 6B). Also, proteasomal inhibition diminishes the marked difference in protein levels between ataxin-3 versions that have an intact or mutated UbS2 (figure 6C). Together, these data indicate that the proteasomal turnover of pathogenic ataxin-3 in cells is also regulated by UbS2.

Figure 6. Turnover of pathogenic ataxin-3 protein is also regulated by UbS2.

A, C) Left: Western blots from HeLa cells transfected as indicated and treated or not with MG132 (4 hours, 15µM) 24 hours after transfection. Right: Means of ataxin-3 signal quantified from blots on the left and other similar experiments. P values are from Student T-tests. Error bars: standard deviations. N of independently conducted experiments is provided in the respective panels.

B) Left: Western blots of HeLa cells transfected as indicated and treated with CHX 24 hours later. Right: Means of ataxin-3 signal quantified from blots on the left and other similar experiments. P values are from Student T-tests. Error bars: standard deviations. N=7 independently conducted experiments.

D) Left: Western blots from at least 10 dissected fly heads for each indicated group. Right: Means of ataxin-3 signal quantified from blots on the left and other similar experiments. P values are from Student T-tests. Error bars: standard deviations. N=8 independent experiments. Flies were 1–2 days old. All flies were heterozygous for UAS-ataxin-3, UAS-Rad23-RNAi (where indicated), and the gmr-Gal4 driver.

E) External photos and internal sections of fly eyes expressing UAS-ataxin-3(SCA3) in the isogenic background of the UAS-RNAi line targeting Rad23 (2nd column), with UAS-RNAi targeting Rad23 (third column), in the isogenic background of Rad23 deficiency (4th column, which is the control for column 5; see main text for description), or in the presence of one copy of Rad23 (deficiency line; 5th column). Driver: gmr-Gal4. Double headed arrows: ommatidial boundaries. Boxes: proteinaceous inclusions that contain ataxin-3(SCA3)6. Control in 1st column contained only gmr-Gal4. The other lines were heterozygous for the gmr-Gal4 driver and UAS-transgenes. Images are representative of sections from at least six flies per group and experiments were conducted independently in triplicate with similar results. Flies were 14 days old. Scale bars in histological sections: 50µM.

Because knockdown of Rad23A/B leads to lower levels of ataxin-3 protein in cultured cells (figure 4C), we reasoned that reducing Rad23 levels in Drosophila should suppress degeneration caused by its pathogenic version by lowering the levels of the polyQ protein. Whereas humans have separate genes for Rad23A and Rad23B, flies appear to have one gene for Rad2321, 23, 24, 55.

We utilized a transgenic fly line generated by the Bonini lab that expresses a full-length version of pathogenic ataxin-3 with 84 polyQ repeats and has intact UbS2, VCP-binding site and UIMs6. First, we examined ataxin-3(SCA3) protein levels in fly eyes when Rad23 levels are reduced by either knocking down this gene through RNAi, or by using a chromosomal deletion in the genomic area that contains Rad23 (line Df(4)ED6369). This deficiency deletes chromosomal segment 102A1--102C1, which includes Rad23 at locus 102B3; these flies are hemizygous viable. As shown in western blots in figure 6D, knocking down Rad23 or removing one copy of this gene leads to lower levels of ataxin-3 in Drosophila eyes. Knocking down other proteins related to ubiquitin (ubiquilin, nedd8 or SUMO, all of which reportedly interact with ataxin-31) does not reduce ataxin-3 protein levels in vivo (supplementary figure 5), indicating a specific role for Rad23 in regulating ataxin-3.

We then examined whether reduction of Rad23 suppresses degeneration caused by pathogenic ataxin-3. When expressed selectively in fly eyes, this ataxin-3 variant does not greatly impact the external eye compared to wild type controls (figure 6E, compare columns I and II). However, retinal sections show marked degeneration (disruption and loss of the radial ommatidial array and less defined inter-ommatidial boundaries) and the presence of densely staining structures/aggregates, which contain pathogenic ataxin-36. As shown in figure 6E column III, knockdown of Rad23 dramatically suppresses degeneration caused by pathogenic ataxin-3 in fly eyes. We recapitulated these findings from the RNAi targeting Rad23 with the deficiency line described above. When we express pathogenic ataxin-3 on a Rad23 hemizygous background, we again observe suppressed SCA3-dependent retinal degeneration (columns IV and V in figure 6E). Together, data in figure 6 indicate that pathogenic ataxin-3 protein is also regulated by UbS2 and Rad23.

DISCUSSION

The degradation of most short-lived, abnormal and misfolded proteins in eukaryotic cells is accomplished by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway20. In this pathway, proteins destined for the proteasome are tagged post-translationally with ubiquitin chains, which enable their recognition by proteasome-associated ubiquitin-binding proteins. Once bound to the proteasome, these ubiquitinated substrates are deubiquitinated and ultimately degraded20. In our search to determine how the disease protein ataxin-3 is degraded, we collected evidence that the turnover of this polyQ protein does not require its own ubiquitination: ataxin-3 that does not become ubiquitinated is degraded similarly to its wild type version in cells and does not accumulate in vivo in Drosophila.

According to a previous report, the E3 ubiquitin ligase CHIP may ubiquitinate ataxin-3 as well as other polyQ proteins to target them for degradation39. Indeed, we previously showed that ataxin-3 is ubiquitinated in mammalian cells and in Drosophila7, 26, 27, 28, and that ubiquitination directly and dramatically enhances its deubiquitinase activity7, 26, 27, 28. However, recent work indicated that CHIP ubiquitinates ataxin-3 to modify its catalytic activity during the process of substrate ubiquitination, where ataxin-3 and CHIP cooperate to enhance CHIP substrate degradation26, 27, 28. Additionally, CHIP knockout mice do not show accumulation of ataxin-3 protein, and knockdown of CHIP in Drosophila does not detectably impact ataxin-3 protein levels7. Based on these previously published findings and our present results, we propose that ubiquitination of ataxin-3 serves to regulate its DUB functions, rather than directly dictate its proteasomal turnover. This is not to say that ubiquitination of ataxin-3 might not enhance its turnover under some circumstances. What our results indicate is that ataxin-3 does not need to be ubiquitinated to be degraded. Other proteins have been reported to be degraded by the proteasome in the absence of their own ubiquitination, including p21/CiP140, calmodulin41, thymidylate synthase42, tau43, etc.44.

We found that ataxin-3 degradation is regulated by its UbS2. Mutation of this domain accelerates the turnover of ataxin-3 in cells and leads to markedly lower levels of this protein in vivo. The general structural organization of the catalytic domain of ataxin-3 appears to not be impacted by mutating residue W87 of UbS2, according to previously published NMR studies21, 23. The localization of full-length ataxin-3(UbS2*) in cultured mammalian cells is not different from versions of this protein with intact UbS2. Full-length ataxin-3 with mutated UbS2 is capable of cleaving ubiquitin chains in vitro23, and this site is dispensable for the ubiquitination-dependent activation of ataxin-3 that we have reported previously23, 26, 27. Based on these findings, mutating UbS2 does not detrimentally impact ataxin-3’s folding and localization, or abrogate its basic catalytic activities.

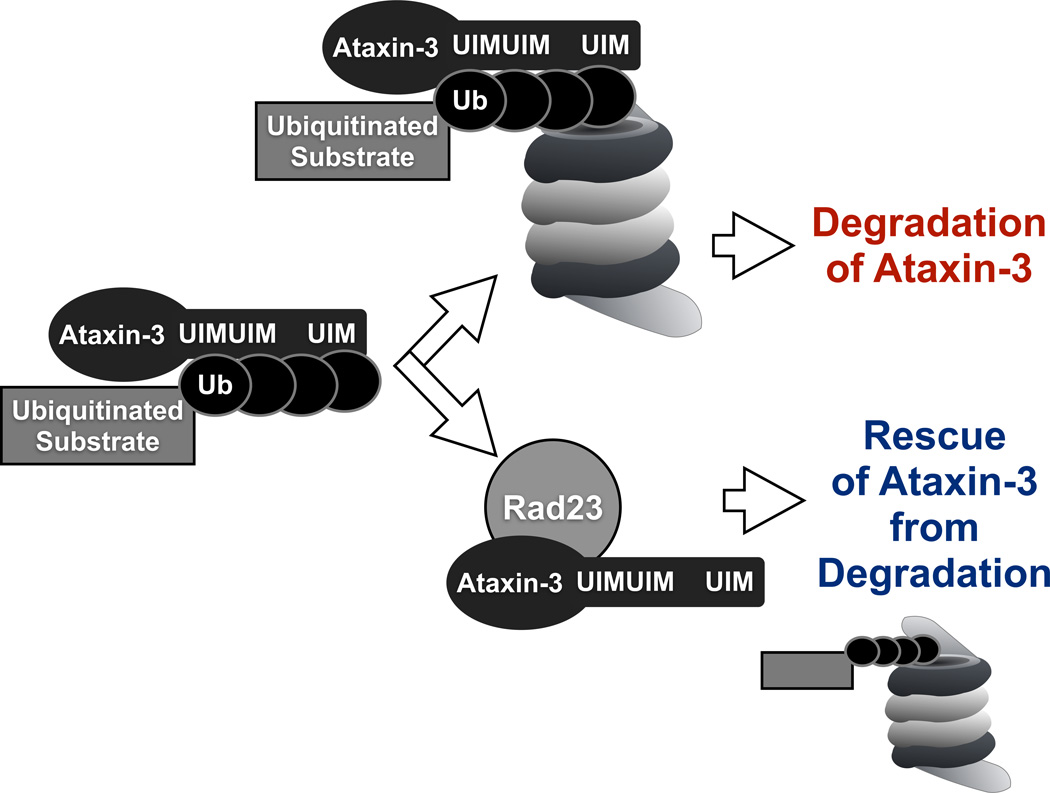

UbS2 binds directly to Rad23A/B21, 22, 23. Knockdown of Rad23A and/or B in cultured cells leads to significantly lower levels of ataxin-3 protein. Importantly, Rad23 knockdown in Drosophila leads to lower levels of pathogenic ataxin-3 and ameliorates retinal degeneration caused by this protein. Based on our collective results, we propose a model for ataxin-3 degradation whereby its UIMs bind ubiquitinated proteasome substrates and “bring” this protein quality control DUB into the proximity of the degradative machinery. Once near the proteasome, the interaction of ataxin-3 with Rad23 prevents it from being degraded, perhaps because the direct binding of this polyQ protein to Rad23 is stronger than its association with the proteasome. If ataxin-3 does not bind Rad23, it is then degraded.

Our finding that UbS2 controls ataxin-3 degradation is of critical importance to SCA3 therapeutics. The structure of the N-terminal half of ataxin3, including UbS2, has been solved by NMR spectroscopy and its interaction with the ubiquitin-like domain of Rad23 has been modeled at this level21, 22, 23. We propose that this structural information be utilized to generate compounds that bind ataxin-3 at UbS2 and inhibit its interaction with Rad23 in order to increase the degradation rate of pathogenic ataxin-3 in SCA3 patients.

The work that we presented might be also of significance to diseases other than SCA3. Rad23A is reported to also interact directly with ataxin-745, mutations in which cause SCA74. It would be of interest to determine if Rad23A inhibits the degradation of ataxin-7, similar to its effect on ataxin-3. Moreover, a recent study by Coulson and colleagues46 provided convincing evidence that ataxin-3 restricts the transcription of the tumor suppressor PTEN. PTEN is considered a viable therapeutic target for various malignancies47, 48. The mechanism of ataxin-3 degradation that we presented leads us to suggest that enhancing the turnover of this enzyme could conceivably be utilized for cancer therapeutics: lowering ataxin-3 levels would be expected to increase the levels of PTEN.

Lastly, our findings suggest additional complexity in basic mechanisms of protein quality control. The general view of proteasome-associated proteins is that they enhance the degradation of client proteins with which they interact34, 49, 50. Our data propose that some proteasome-associated proteins, e.g. Rad23, can also inhibit, not just enhance, protein turnover. This novel finding suggests that proteasome shuttles need not always function in one direction, and expands the overall understanding of how individual components perform during protein quality control.

METHODS

Cell lines

HeLa and HEK-293 cells were purchased from ATCC and were grown in DMEM + 10% FBS under conventional tissue culture conditions.

Constructs

HA-tagged ataxin-3 constructs are in pCDNA3.1-HA; this includes all non-pathogenic ataxin-3 variants. Mutations were generated on the wild type ataxin-3 backbone using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Agilent). FLAG-tagged ataxin-3 constructs are in pFLAG6a (Sigma-Aldrich)25, 26, 29; this includes the pathogenic ataxin-3 variants. Mutations in these constructs were also conducted using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Agilent). Where noted, lysine residues in ataxin-3 were mutated into the similar but non-ubiquitinatable amino acid arginine7, 27. RNAi constructs targeting Rad23A or B in mammalian cells were purchased from Invitrogen. Catalog numbers: s11729, s11730, s11731, s11733.

Transfections

Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine LTX (Invitrogen) as directed by the manufacturer for all constructs, except for siRNA, where we used Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen).

SDS-PAGE

Cells were harvested for SDS-PAGE in boiling 2% SDS lysis buffer (50mM Tris pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 100mM DTT)25, 29, 51, boiled for 10 minutes, centrifuged, loaded onto 10% or 4%–20% SDS-PAGE gels, electrophoresed at 150–180V and transferred onto PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad) for western blotting.

Antibodies

Anti-ataxin-3 (MJD; rabbit polyclonal, 1:15,00052), anti-ataxin-3 monoclonal (clone 1H9, mouse, 1:500–1:1,000; Millipore), anti-HA (rabbit polyclonal Y11, 1:500; Santa Cruz Biotech), anti-Tubulin (mouse monoclonal T5168, 1:10,000; Sigma-Aldrich), anti-GAPDH (mouse monoclonal MAB374, 1:500; Millipore), anti-Rad23A (rabbit polyclonal YH62308, 1:5,000; Origene), anti-Rad23B (rabbit polyclonal A302–306A, 1:2,000; Bethyl Labs), peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit and goat anti-mouse, 1:5,000; Jackson Immunoresearch).

Western blotting and signal quantification

Western blots were imaged with a CCD-equipped VersaDoc 5000MP system (Bio-Rad)26, 27, 29. Quantification of signals from sub-saturated blots was conducted in the Quantity One software (Bio-Rad) with universal background subtraction. Signal from the protein of interest was normalized to its own loading control (tubulin or GAPDH). Experimental lanes were normalized to respective controls. Student T-tests with two tails and ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc correction were used for statistical comparisons, as specified in the figure legends. Full western blots for images in figures 1–6 are shown in supplementary figure 6.

Chemicals

Cycloheximide (CHX) was purchased from A.G. Scientific, dissolved in ultra-pure water and used at final concentration of 50 µg/ml. MG132 was purchased from A.G. Scientific, dissolved in DMSO and utilized at final concentrations specified in figure legends.

Drosophila lines

Common stocks and the line expressing pathogenic ataxin-3 (stock number 33610 with genotype w[1118]; P{w[+mC]=UAS-SCA3.fl-Q84.myc}7.2/MKRS) were purchased from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center. The UAS-RNAi line targeting Rad23 and its isogenic background were purchased from the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center (transformants 30498 and 60000). The Rad23 deficiency line was purchased from Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (stock number: 9422 with genotype w[1118]; Df(4)ED6369, P{w[+mW.Scer\FRT.hs3]=3'.RS5+3.3'}ED6369 / l(4)102EFf[1]). Non-pathogenic UAS-ataxin-3 flies were generated by us, using ataxin-3 with a polyQ repeat of 22 residues cloned into the pUASt vector. Injections were done by the Duke University Model System Genomics into the w1118 background7. All fly lines were on a w[−] background. Flies were maintained in a diurnally controlled 25°C environment at ~60% humidity. Whole flies or dissected heads were homogenized in boiling SDS lysis buffer (50mM Tris pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 100mM DTT), sonicated, boiled for 10 minutes, centrifuged to remove debris, loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels, electrophoresed and transferred onto PVDF membrane for western blotting7, 53. We used 5–10 whole flies or 10–15 heads per group, and 50µL lysis buffer per whole fly or 10µL per dissected head. Analysis of Drosophila samples was conducted in a blinded manner. Choice of sample size for Drosophila studies was based on common practices among fly labs. No samples were excluded from analyses.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cultured mammalian cells or 1–3 day-old adult flies using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen). Extracted RNA was treated with TURBO DNAse (Ambion) to eliminate contaminating DNA. Reverse transcription was performed with the High Capacity Kit (ABI) and messenger RNA levels were quantified by using the PlusOne real-time quantitative system with fast SYBR green (ABI). Rp49 and GAPDH were used as internal controls. Primers: Rp49-F: AGATCGTGAAGAAGCGCACCAAG, RP49-R: CACCAGGAACTTCTTGAATCCGG; GAPDH-F: GCTCAGACACCATGGGGAAGGT, GAPDH-R: GTGGTGCAGGAGGCATTGCTGA; ataxin-3 in flies: AT3-F: GAATGGCAGAAGGAGGAGTTACTA AT3-R: GACCCGTCAAGAGAGAATTCAAGT; ataxin-3 in mammalian cells: AT3-F: TTCCAGATTACGCTTCTAGAGGAT, AT3-R: TAGTAACTCCTCCTTCTGCCATTC.

Fly histology

Whole flies with removed proboscises were fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde/2% paraformaldehyde in Tris-Buffered Saline overnight. Fixed flies were then dehydrated in a series of 30%, 50%, 75% and 100 % ethanol and propylene oxide, embedded in Poly/Bed812 (Polysciences) and sectioned at 5 µm. Sections were stained with toluidine blue.

Supplementary Material

Figure 7. Proposed model of ataxin-3 degradation.

According to this model, ataxin-3 comes into physical contact with the proteasome by binding to ubiquitinated proteins through its UIMs in the C-terminal portion. Once at the proteasome, in the absence of interaction with Rad23A/B through UbS2, ataxin-3 is degraded by the proteasome. If UbS2 interacts with Rad23A/B, ataxin-3 is rescued from degradation, perhaps as a result of higher affinity for Rad23A/B compared to the proteasome.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by R00NS064097 and R01NS086778 to SVT from NINDS, by awards to SVT and WL-T from the National Ataxia Foundation, by a T32 training slot to AAB (CA009531), and by R00NS073936 to KMS from NINDS.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Designed experiments: JRB, WL-T, KMS, SVT

Conducted experiments: JRB, WL-T, GR, AAB, MO, HG, KMS, SVT

Analyzed data: JRB, WL-T, GR, AAB, KMS, SVT

Prepared figures: JRB, WL-T, KMS, SVT

Wrote manuscript: WL-T, KMS, SVT

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Costa Mdo C, Paulson HL. Toward understanding Machado-Joseph disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 2012;97:239–257. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Todi SV, Williams A, Paulson HL. Polyglutamine Repeat Disorders, including Huntington’s Disease. In: Waxman SG, editor. Molecular Neurology. 1st edition. Academic Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams AJ, Paulson HL. Polyglutamine neurodegeneration: protein misfolding revisited. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:521–528. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orr HT, Zoghbi HY. Trinucleotide repeat disorders. Ann. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;30:575–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reina CP, Zhong X, Pittman RN. Proteotoxic stress increases nuclear localization of ataxin-3. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010;19:235–249. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warrick JM, Morabito LM, Bilen J, Gordesky-Gold B, Faust LZ, Paulson HL, Bonini NM. Ataxin-3 suppresses polyglutamine neurodegeneration in Drosophila by a ubiquitin-associated mechanism. Mol. Cell. 2005;18:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsou W-L, Burr AA, Ouyang M, Blount JR, Scaglione KM, Todi SV. Ubiquitination regulates the neuroprotective function of the deubiquitinase ataxin-3 in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:34460–34469. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.513903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pedersen JT, Heegaard NH. Analysis of Protein Aggregation in Neurodegenerative Disease. Anal. Chem. 2013;85:8254–8261. doi: 10.1021/ac400023c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez-Lebron E, Gouvion CM, Moore SA, Davidson BL, Paulson HL. Allele-specific RNAi mitigates phenotypic progression in a transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease. Mol. Ther. 2009;17:1563–1573. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alves S, Nascimento-Ferreira I, Dufour N, Hassig R, Auregan G, Nobrega C, Brouillet E, Hantraye P, Pedroso de Lima MS, Deglon N, de Almeida LP. Silencing ataxin-3 mitigates degeneration in a rat model of Machado-Joseph disease: no role for wild-type ataxin-3? Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010;19:2380–2394. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alves S, Regulier E, Nascimento-Ferreira I, Hassig R, Dufour N, Koeppen A, Carvalho AL, Simoes S, de Lima MC, Brouillet E, Gould VC, Deglon N, de Almeida LP. Striatal and nigral pathology in a lentiviral rat model of Machado-Joseph disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008;17:2071–2083. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams AJ, Knutson TM, Colomer Gould VF, Paulson HL. In vivo suppression of polyglutamine neurotoxicity by C-terminus of Hsp70-interacting protein (CHIP) supports an aggregation model of pathogenesis. Neurobiol. Dis. 2009;33:342–353. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harper SQ, Staber PD, He X, Eliason SL, Martins IH, Mao Q, Yang L, Kotin RM, Paulson HL, Davidson BL. RNA interference improves motor and neuropathological abnormalities in a Huntington's disease mouse model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2005;102:5820–5825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501507102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xia H, Mao Q, Eliason SL, Harper SQ, Martins IH, Orr HT, Paulson HL, Yang L, Kotin RM, Davidson BL. RNAi suppresses polyglutamine-induced neurodegeneration in a model of spinocerebellar ataxia. Nat. Med. 2004;10:816–820. doi: 10.1038/nm1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsou WL, Soong BW, Paulson HL, Rodriguez-Lebron E. Splice isoform-specific suppression of the Cav2.1 variant underlying spinocerebellar ataxia type 6. Neurobiol. Dis. 2011;43:533–542. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alves S, Nascimento-Ferreira I, Auregan G, Hassig R, Dufour N, Brouillet E, Pedroso de Lima MC, Hantraye P, de Almedia LP, Deglon N. Allele-specific RNA silencing of mutant ataxin-3 mediates neuroprotection in a rat model of Machado-Joseph disease. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bove J, Martinez-Vicente M, Vila M. Fighting neurodegeneration with rapamycin: mechanistic insights. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011;12:437–452. doi: 10.1038/nrn3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.do Carmo Costa M, Luna-Cancalon K, Fischer S, Ashraf NS, Ouyang M, Dharia RM, Martin-Fishman L, Yang Y, Shakkottai VG, Davidson BL, Rodriguez-Lebron E, Paulson HL. Toward RNAi Therapy for the Polyglutamine Disease Machado-Joseph Disease. Mol. Ther. 2013;21:1898–1908. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nobrega C, Nascimento-Ferreira I, Onofre I, Albuqurque D, Hirai H, Deglon N, de Almeida LP. Silencing mutant ataxin-3 rescues motor deficits and neuropathology in machado-joseph disease transgenic mice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e52396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heride C, Urbe S, Clague MJ. Ubiquitin code assembly and disassembly. Curr. Biol. 2014;24:215–220. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicastro G, Masino L, Esposito V, Menon RP, De Simone A, Fraternali F, Pastore A. Josephin domain of ataxin-3 contains two distinct ubiquitin-binding sites. Biopolymers. 2009;91:1203–1214. doi: 10.1002/bip.21210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicastro G, Menon RP, Masino L, Knowles PP, McDonald NQ, Pastore A. The solution structure of the Josephin domain of ataxin-3: structural determinants for molecular recognition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2005;102:10493–10498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501732102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicastro G, Todi SV, Karaca E, Bonvin AM, Paulson HL, Pastore A. Understanding the role of the Josephin domain in the PolyUb binding and cleavage properties of ataxin-3. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang G, Sawai N, Kotliarova S, Kanazawa I, Nukina N. Ataxin-3, the MJD1 gene product, interacts with the two human homologs of yeast DNA repair protein RAD23, HHR23A and HHR23B. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:1795–1803. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.12.1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Todi SV, Laco MN, Winborn BJ, Travis SM, Wen HM, Paulson HL. Cellular turnover of the polyglutamine disease protein ataxin-3 is regulated by its catalytic activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:29348–29358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704126200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Todi SV, Winborn BJ, Scaglione KM, Blount JR, Travis SM, Paulson HL. Ubiquitination directly enhances activity of the deubiquitinating enzyme ataxin-3. EMBO J. 2009;28:372–382. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Todi SV, Scaglione KM, Blount JR, Basrur V, Conlon KP, Pastore A, Elenitoba-Johnson K, Paulson HL. Activity and cellular functions of the deubiquitinating enzyme and polyglutamine disease protein ataxin-3 are regulated by ubiquitination at lysine 117. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:39303–39313. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.181610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scaglione KM, Zavodszky E, Todi SV, Patury S, Xu P, Rodriguez-Lebron E, Fischer S, Konen J, Djarmati A, Peng J, Gestwicki JE, Paulson HL. Ube2w and Ataxin-3 Coordinately Regulate the Ubiquitin Ligase CHIP. Mol. Cell. 2011;43:599–612. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winborn BJ, Travis SM, Todi SV, Scaglione KM, Xu P, Williams AJ, Cohen RE, Peng J, Paulson HL. The deubiquitinating enzyme ataxin-3, a polyglutamine disease protein, edits Lys63 linkages in mixed linkage ubiquitin chains. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:26436–26443. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803692200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brand AH, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 1993;118:401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Todi SV, Franke JD, Kiehart DP, Eberl DF. Myosin VIIA defects, which underlie the Usher 1B syndrome in humans, lead to deafness in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:862–868. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.03.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franke JD, Boury AL, Gerald NJ, Kiehart DP. Native nonmuscle myosin II stability and light chain binding in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 2006;63:604–622. doi: 10.1002/cm.20148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buchberger A, Bukau B, Sommer T. Protein quality control in the cytosol and the endoplasmic reticulum: brothers in arms. Mol. Cell. 2010;40:238–252. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dantuma NP, Heinen C, Hoogstraten D. The ubiquitin receptor Rad23: at the crossroads of nucleotide excision repair and proteasomal degradation. DNA Repair. 2009;8:449–460. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boeddrich A, Gaumer S, Haacke A, Tzvetkov N, Albrecht M, Evert BO, Muller EC, Lurz R, Breuer P, Schugardt N, Passmann S, Xu K, Warrick JM, Suopanki J, Wullner U, Frank R, Hartl UF, Bonini NM, Wanker EE. An arginine/lysine-rich motif is crucial for VCP/p97-mediated modulation of ataxin-3 fibrillogenesis. EMBO J. 2006;25:1547–1558. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morreale G, Conforti L, Coadwell J, Wilbrey AL, Coleman MP. Evolutionary divergence of valosin-containing protein/cell division cycle protein 48 binding interactions among endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation proteins. FEBS J. 2009;276:1208–1220. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhong X, Pittman RN. Ataxin-3 binds VCP/p97 and regulates retrotranslocation of ERAD substrates. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006;15:2409–2420. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shoesmith Berke SJ, Chai Y, Marrs GL, Wen H, Paulson HL. Defining the role of ubiquitin interacting motifs in the polyglutamine disease protein, ataxin-3. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:32026–32034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506084200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jana NR, Dikshit P, Goswami A, Kotliarova S, Murata S, Tanaka K, Nukina N. Co-chaperone CHIP associates with expanded polyglutamine protein and promotes their degradation by proteasomes. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:11635–11640. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412042200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sheaff RJ, Singer JD, Swanger J, Smitherman M, Roberts JM, Clurman BE. Proteasomal turnover of p21Cip1 does not require p21Cip1 ubiquitination. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:403–410. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80435-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tarcsa E, Szymanska G, Lecker S, O'Connor CM, Goldberg AL. Ca2+-free calmodulin and calmodulin damaged by in vitro aging are selectively degraded by 26 S proteasomes without ubiquitination. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:20295–20301. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001555200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Forsthoefel AM, Pena MM, Xing YY, Rafique Z, Berger FG. Structural determinants for the intracellular degradation of human thymidylate synthase. Biochemistry. 2004;43:1972–1979. doi: 10.1021/bi035894p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blair LJ, Nordhues BA, Hill SE, Scaglione KM, O’Leary JC, 3rd, Fontaine SN, Breydo L, Zhang B, Li P, Wang L, Cotman C, Paulson HL, Muschol M, Uversky VN, Klengel T, Binder EB, Kayed R, Golde T, Berchtold N, Dickey CA. Accelerated neurodegeneration through chaperone-mediated oligomerization of tau. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:4158–4169. doi: 10.1172/JCI69003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoyt MA, Coffino P. Ubiquitin-free routes into the proteasome. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2004;61:1596–1600. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4133-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lim J, Hao T, Shaw C, Patel AJ, Szabo G, Rual JF, Fisk CJ, Li N, Smolyar A, Hill DE, Barabasi AL, Vidal M, Zoghbi HY. A protein-protein interaction network for human inherited ataxias and disorders of Purkinje cell degeneration. Cell. 2006;125:801–814. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sacco JJ, Yau TY, Darling S, Patel V, Liu H, Urbe S, Clague MJ, Coulson JM. The deubiquitylase Ataxin-3 restricts PTEN transcription in lung cancer cells. Oncogene. 2013 doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Song MS, Salmena L, Pandolfi PP. The functions and regulation of the PTEN tumour suppressor. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2012;13:283–296. doi: 10.1038/nrm3330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leslie NR, Foti M. Non-genomic loss of PTEN function in cancer: not in my genes. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2011;32:131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Claessen JH, Kundrat L, Ploegh HL. Protein quality control in the ER: balancing the ubiquitin checkbook. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;22:22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamanaka K, Sasagawa Y, Ogura T. Recent advances in p97/VCP/Cdc48 cellular functions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1823:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blount JR, Burr AA, Denuc A, Marfany G, Todi SV. Ubiquitin-specific protease 25 functions in Endoplasmic Reticulum-associated degradation. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36542. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Paulson HL, Perez MK, Trottier Y, Trojanowski JQ, Subramony SH, Das SS, Vig P, Madel JL, Fischbeck KH, Pittman RN. Intranuclear inclusions of expanded polyglutamine protein in spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. Neuron. 1997;19:333–344. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80943-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsou W-L, Sheedlo MJ, Morrow ME, Blount JR, McGregor KM, Das C, Todi SV. Systematic Analysis of the Physiological Importance of Deubiquitinating Enzymes. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43112. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scaglione KM, Basrur V, Ashraf NS, Konen RJ, Elenitoba-Johnson KS, Todi SV, Paulson HL. The ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) Ube2w ubiquitinates the N terminus of substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:18784–18788. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C113.477596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.A database of Drosophila genes & genomes. 2014 Flybase.org. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.