Abstract

Inherited primary arrhythmias, namely congenital long QT syndrome, Brugada syndrome and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, account for a significant proportion of sudden cardiac deaths in young and apparently healthy individuals. Genetic testing plays an integral role in the diagnosis, risk-stratification and treatment of probands and family members. It is increasingly obvious that collaborative efforts are required to understand and manage these relatively rare but potentially lethal diseases. This article aims to update readers on the recent developments in our knowledge of inherited arrhythmias and to lay the foundation for a national synergistic effort to characterize them in the Indian population.

Keywords: Cardiac channelopathies, Family screening, Genetic testing, Inherited arrhythmias, Sudden cardiac death

Inherited primary arrhythmia syndromes are electrical abnormalities of the heart caused by derangements in the structure and function of the cardiac ion channels. Since a majority of the primary arrhythmias are due to mutations in the genes encoding the ion channels of the heart, namely Na+, K+ and Ca++ channels, they are referred to as “cardiac ion channelopathies”.1 These are typically monogenic disorders, that is, disorders that follow a clear Mendelian pattern of inheritance, although for some of them a more complex pattern emerges.2 They are most often inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, which explains the strong role for family screening in the management of affected patients.3 Autosomal recessive inheritance and the occurrence of de novo mutations are also seen but less frequently.

Sudden cardiac death (SCD), defined as death from a cardiac cause occurring shortly after the onset of symptoms, is most often due to an organic cardiac abnormality, such as coronary artery disease or structural heart disease. However, death in young, active and previously healthy individuals with no identifiable cause on autopsy, termed sudden arrhythmic death syndrome (SADS), constitutes up to 5% of SCD in the general population aged 16–64 years and almost 25–35% of sudden deaths in the <40 years age group.4 When sudden death of unknown aetiology occurs in a child <1 year of age, it is termed sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), and has a current annual incidence of about 50/100,000 in the United States.4,5 Unravelling the mystery surrounding SADS and SIDS has been the focus of numerous research efforts recently. As a result of this increased interest as well as the concurrent advances in the molecular, genetic, experimental and clinical aspects of medicine, we have witnessed an exponential increase in knowledge on the genetic background of SCD in the recent past. Inherited arrhythmia syndromes play an integral role in this ever-expanding realm of young unexpected deaths and are currently implicated in about 20–35% of cases as shown by post-mortem genetic testing, also termed molecular autopsy.6–8

The flow of ions into and out of the cardiac myocyte is so delicately balanced that neither a loss nor a gain of the ionic channel function is tolerated by the intricately functioning electrical system of the heart. Based on whether the functional derangement caused by the underlying genetic abnormality is a decrease or an increase in ionic conduction, the channelopathies are categorized as loss-of-function or a gain-of-function channelopathies. The three main groups of channelopathies contributing to the majority of genotype positive patients are congenital long QT syndrome (LQTS), catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) and Brugada syndrome (BrS) and related phenotypes; the less common entities being short QT syndrome (SQTS), early repolarization syndrome (ERS) and idiopathic ventricular fibrillation (IVF).9

Cardiac channelopathies, together with cardiomyopathies, account for a wide spectrum of genetically inherited heart rhythm disorders, the diagnosis and management of which is the core purpose of the multidisciplinary ‘inherited heart disease clinics’ being established around the globe.4 With the establishment of a strong link between genetic mutations and life-threatening arrhythmias, and with the availability of solid scientific evidence for marked reduction in morbidity and mortality by early identification and appropriate treatment of diseased individuals, there is a pressing need for countries like India to incorporate genetic testing into the routine management of patients with inherited arrhythmias. This article aims to provide an update on the diagnostic and therapeutic aspects of the channelopathies and to lay the foundation for a national collaborative effort to study these relatively rare but vastly unexplored and preventable causes of death in the Indian subcontinent.

1. Congenital long QT syndrome (LQTS)

LQTS encompasses a heterogeneous family of disorders characterized by delayed cardiac repolarization and a propensity to syncope and SCD.10 Torsades de Pointes (TdP), an often self-limiting ventricular tachyarrhythmia, is the mechanism behind the transient syncope in affected patients. TdP, however, has the potential to degenerate into ventricular fibrillation and has to be treated aggressively. The estimated prevalence of LQTS is ∼1:2000 in the western world.11 Heart rate corrected QT (QTc) interval prolongation on the surface electrocardiogram (ECG) is the hallmark feature of LQTS; but we know that due to incomplete disease penetrance and variable expressivity, genetically affected individuals may have a normal ECG.12 Sixteen genes have so far been identified as responsible for or associated with LQTS.13 The three main genes, KCNQ1 (LQT1), KCNH2 (LQT2) and SCN5A (LQT3) account for 75% of clinically definite cases of LQTS and the minor genes together account for another 5%. The genetic underpinnings of about 20% of LQTS are yet to be unravelled.

LQT1 and LQT2 are caused by loss-of-function mutations in the genes encoding the α subunits of two different cardiac K+ channels, responsible for the ionic currents IKs and IKr, respectively. Each of the types accounts for approximately 40% of genotype-positive LQTS patients.14 LQT3, on the other hand, is caused by gain-of-function mutations of the SCN5A gene encoding the α subunit of the cardiac Na+ channel, causing an increase in persistent inward sodium current (INaL) during myocardial repolarization.15 Although predominantly of autosomal dominant inheritance, a severe recessive form of LQTS, termed Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome occurs rarely and is associated with congenital deafness and severe QTc prolongation.16,17 Since the identification of the three major LQTS genes in the early to mid-90's, not only has our understanding of the genotype–phenotype correlations of LQTS broadened significantly but also mutations in other associated genes and their regulatory proteins have become known, paving the way for genotype-specific management. Recently, the calmodulin genes, CALM1 and CALM2, have been discovered to play a role in the causation of an extremely severe form of LQTS. QT prolongation >600 ms, T-wave alternans, cardiac arrest in infancy, multiple episodes of ICD-terminated ventricular fibrillation mostly triggered by sympathetic activation, and poor response to pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions are observed to be the characteristics of these mutations.18 Another interesting revelation has been that of the influence of genetic modifiers on disease expression in LQTS patients. For instance, common variants in the NOS1AP gene, originally tagged in association with variable QT interval duration in the healthy population, have been demonstrated to be modifiers of both the QT interval and the probability of symptoms in LQTS.19 Also, common variants in the 3′ untranslated region of KCNQ1 have been shown to modify disease severity in an allele-specific manner.20

2. Brugada syndrome (BrS)

BrS is the best described of the loss-of-function sodium (Na+) channelopathies where a loss or a reduction of Na+ channel function is caused by mutations in the SCN5A gene and its associated proteins.21 BrS is primarily a clinical diagnosis. Nevertheless, fourteen genes are currently implicated in the causation of BrS and its related phenotypes and about a third of all BrS probands exhibit genotype positivity. Some of the newly identified but rarer genes are Na+ channel β-subunits (SCN1B and SCN3B), L-type calcium channels (CACNA1C, CACNB2b and CACNA2D1), glycerol-3-phophate dehydrogenase 1-like enzyme gene (GPD1L), KCNE3, KCNJ8, KCND3, Ankyrin-G and MOG1.22 Very recently, the concept that BrS is a monogenetic disease has been challenged. Indeed, an extended genome-wide association study provided evidence that the presence of a combination of relatively common genetic variants in the right genes might be sufficient to produce the signature ECG pattern.2

Syncope, polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and SCD are the commonest manifestations of the disease. BrS is typically diagnosed by the ECG finding of a coved ST segment and J-point elevation ≥0.2 mV followed by a negative T wave, termed Type 1 Brugada pattern, in two or more right precordial leads in a symptomatic individual with a structurally normal heart (Fig. 1).4 Drug challenge with sodium channel blockers such as flecainide or ajmaline is quite often used to unmask the concealed Type 1 Brugada pattern. Also featuring in the continuum of conduction abnormalities caused by loss-of-function Na+ channelopathies are progressive cardiac conduction disease, familial atrial fibrillation and sick sinus syndrome. Although predominantly a disease of middle-aged men, BrS spectrum of diseases have been documented in infants and young children of both sexes.23 In this age group (<2 years of age), rapid wide complex (monomorphic) ventricular tachycardia and/or prolonged conduction intervals are frequent signs of underlying genetic aberrations.24 In contrast to affected adults, young children rarely exhibit the typical Type 1 Brugada pattern on their ECG.25 Fever, a common entity in the pediatric population as well as an established arrhythmia trigger in BrS patients, often plays a significant role in exposing the young patients harbouring these channelopathies.26

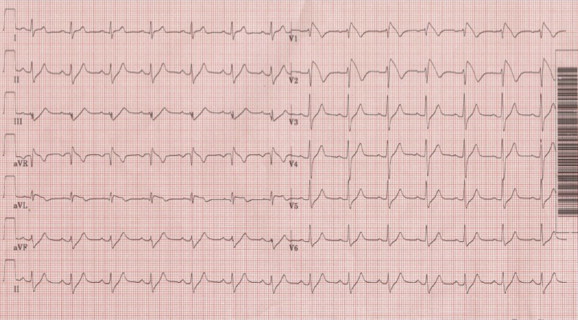

Fig. 1.

Standard 12-lead ECG showing coved ST segment and J-point elevation ≥0.2 mV followed by a negative T wave, termed Type 1 Brugada pattern, in the right precordial leads V1 and V2.

3. Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT)

An adrenergic-mediated disease initially described in children, CPVT is characterized by bidirectional or polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in a setting of physical exercise or emotional stress.27 A Holter recording and/or an exercise stress test quite often help to clinch the diagnosis in a young patient presenting with syncope or cardiac arrest and with a normal resting ECG and normal echocardiography. CPVT is a highly penetrant autosomal dominant disease with SCD often being the presenting symptom; hence family screening is an absolute prerequisite to catch disease early and to initiate treatment. Mutations in the cardiac ryanodine receptor (RYR2) gene are present in 55–65% of probands while cardiac calsequestrin (CASQ2) gene mutations, inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, account for about 2% cases.10 Both genes are involved in the release of calcium ions from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, for excitation–contraction coupling. Early onset of symptoms, particularly before the age of 5, is associated with a poor prognosis and male carriers have a fourfold greater risk of cardiac events than the female counterparts.

4. Other channelopathies

Short QT syndrome (SQTS), a rare channelopathy, is diagnosed in the presence of a QTc ≤330 ms. or a QTc <360 ms and one or more of the following: a pathogenic mutation, family history of SQTS, family history of sudden death at age ≤40, survival of a VT/VF episode in the absence of heart disease.4 So far, gain-of-function DNA variants in 3 potassium channel genes (KCNH2, KCNQ1, KCNJ2) have been described to associate with SQTS. Not surprisingly, loss-of-function mutations of the same genes are responsible for LQTS variants.

Idiopathic ventricular fibrillation (IVF), as the term suggests, refers to spontaneous ventricular fibrillation in patients with structurally normal hearts, the cause of which remains unknown after detailed cardiac and extracardiac evaluation.28 The last decade has witnessed significant revelations concerning IVF and its association with early repolarization,29 SCN5A mutations,30 and with DPP6, a founder mutation causative of a highly lethal form of familial IVF in The Netherlands.31 With more and more information becoming available on the plausible pathogenetic mechanisms of what was considered ‘idiopathic’ earlier, our understanding of the pathophysiology of SCD is also rapidly expanding.

5. The channelopathic approach to diagnosis

The key components in establishing a diagnosis of a channelopathy are a thorough evaluation of the presenting symptom(s), systematic retrieval of the relevant historical clues and a prudent approach to investigative procedures. Since affected patients may first present to their family doctors, paediatricians or neurologists, it is imperative that all physicians and not just cardiologists are aware of and can identify the signs of an underlying inherited cardiac pathology.

5.1. Presenting symptom(s)

Syncope (transient loss of consciousness), resuscitated SCD (sudden cardiac arrest requiring external defibrillation) and SCD are the most commonly encountered symptoms in channelopathies while palpitation, breath-holding spells, seizure-like episodes and extracardiac findings (for example congenital deafness) are the rarer presentations. As far as syncope is concerned, it is considered one of the most challenging dilemmas for a clinician because on one hand, it could be as innocent as a vasovagal syncope, and on the other as lethal as a TdP-related syncope. Probing the circumstances under which the syncope occurred and performing a tilt-table test might help to differentiate the pathologies.32 Syncope is such an integral part of neurology and cardiology practice that several hospitals run a syncope clinic to address the needs of patients. The circumstances of occurrence of symptoms often serve to raise suspicion of the underlying pathology in many of the channelopathies. Any cardiac event triggered by physical exercise, particularly swimming, is suggestive of LQT1 while that associated with sudden loud auditory stimuli such as wake-up alarms or telephone bells are more likely to be LQT2 related.33,34 Syncope mediated by an emotional upset, for instance while being reprimanded by the teacher, could be suggestive of either LQT1 or LQT2. As both physical and emotional stimuli are physiologically linked with a catecholaminergic surge, it should be remembered that CPVT could also manifest with syncope or sudden death during adrenergic upheavals. Events during sleep or rest are shown to be suggestive of an SCN5A abnormality namely LQT3 or BrS. Fever, either documented at the time of the event or mentioned during history taking, is an important clue to a channelopathic cause of disease, particularly loss-of-function sodium channelopathies.

5.2. History-taking

Systematic history-taking, carried out with care for detail, goes a long way in establishing or excluding a diagnosis of channelopathies in an index patient.35 Apart from elaborating on the history of presenting symptoms, the family history and medication history have to be dealt with in length. Asking if any family member has died suddenly and unexpectedly will not suffice. Ideally, a pedigree chart should be drawn which includes at least three generations. History of syncope, palpitation, pacemaker implant, suspected seizures, recurrent abortions, young unexplained SCD or any other cardiac diagnosis should be elicited in all first degree family members, that is parents, siblings and offsprings in case of an adult, and in siblings, maternal and paternal relatives and grandparents in case the proband is a child. History of drug intake and electrolyte status at the time of event occurrence is extremely relevant in order to rule out a possible acquired cause for the presentation. There is a definite and clear-cut role for a nurse specialist and a genetic counsellor, as part of the multidisciplinary cardiogenetic team, in the initial evaluation and subsequent counselling of patients and family members.4

5.3. Electrocardiogram (ECG)

A standard 12-lead resting ECG is an integral part of evaluating a suspected case of channelopathy. However, we have to recognize that there are situations such as a failed resuscitation setting or an intrauterine arrhythmia where a 12-lead ECG might not be readily available but alternatives could be utilized. A systematic scrutiny of all aspects of the ECG should be carried out as atrial and/or ventricular depolarization and repolarization abnormalities may coexist. Accurate measurement of the conduction intervals is a definite requirement in the evaluation of patients with suspected channelopathies. The QT interval is measured manually from the beginning of the QRS complex to the end of the T wave in lead II or V5. The end of the T wave is the intersection point between the isoelectric baseline and the tangent representing the maximal downward slope of the positive T wave or maximal upward slope of the negative T wave.36 The mean of three consecutive QT intervals is calculated and QTc is obtained using the Bazett's formula (QT/√RR). Different repolarization patterns on the ECG are associated with different genotypes: broad based prolonged T wave in LQT1, low amplitude moderately delayed T wave in LQT2, and the late appearing non-distinct T wave in LQT3 (Fig. 2). The PR interval and QRS duration can be prolonged in BrS-like phenotypes and should be scrutinized. The typical coved ST segment pattern of BrS in the precordial leads should not be missed. Any type of arrhythmia, such as atrial fibrillation, sinus bradycardia, monomorphic or polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, TdP and ventricular fibrillation could be the manifestation of an arrhythmia syndrome.

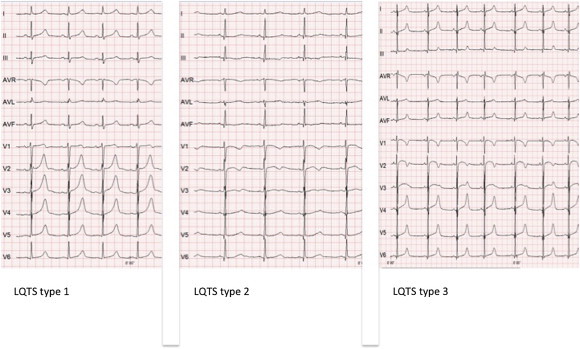

Fig. 2.

Standard 12-lead ECGs of LQTS types 1, 2 and 3. Note the prolonged QTc in all three ECGs and the broad based prolonged T wave in LQTS type 1, low amplitude moderately delayed T wave in type 2, and the late appearing non-distinct T wave in type 3.

In patients with symptoms suggestive of channelopathies and an apparently normal resting ECG (Fig. 3), exercise ECG, lying-standing test, Holter ECG, or an implantable loop recorder may provide additional clues to diagnosis. The QTc values during recovery phase of an exercise test aid in the diagnostic process of LQTS as well as to predict the type of LQTS.37 The lying-standing test has also been shown to have diagnostic value in patients with LQTS.38 The appearance of bidirectional or polymorphic ventricular tachycardia during exercise and the resolution of the same during the recovery phase is a classical sign of CPVT (Fig. 4). Drug challenge with Na+ channel blockers such as flecainide, procainamide and ajmaline is used in better characterization of the not-so-typical ECG signs of BrS and epinephrine provocation is used in patients with a clinical suspicion of LQTS. Although prompt recognition of disease and application of established interventions lead to a significant reduction in mortality, delayed diagnosis of channelopathies is not uncommon. The most common alternative diagnoses are seizure disorder in LQTS patients, atypical febrile seizures in pediatric patients with fever related events, and SIDS in infants with an undiagnosed channelopathy who die suddenly. An elaborate family history together with the recording of an ECG is therefore mandatory in all patients presenting with an EEG-negative seizure disorder, in young children with atypical seizures during pyrexia and (if warranted) in the first-degree family members of SIDS cases. While diagnosing patients with a clearly prolonged QTc (>500 ms) is usually straightforward, challenges arise when QTc values lie in the normal or borderline zone.

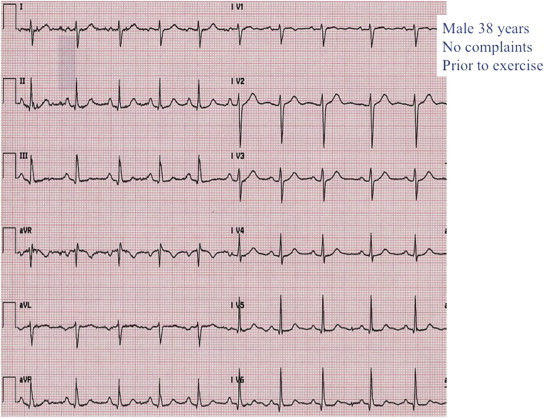

Fig. 3.

Normal resting ECG in a 38-year-old asymptomatic male sibling of a CPVT patient.

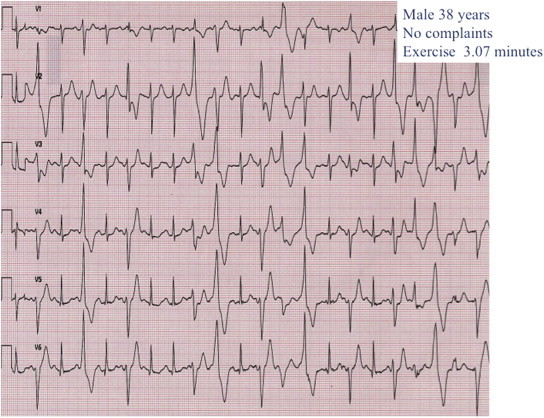

Fig. 4.

Exercise ECG of a 38-year-old asymptomatic male sibling of a CPVT patient showing bidirectional polymorphic ventricular tachycardia.

5.4. Other investigations

Echocardiography is a very useful tool in the evaluation of a young symptomatic patient, particularly because an abnormal echocardiographic examination is not expected in the pure channelopathic spectrum of diseases and also because the more common diagnoses of cardiomyopathies and structural heart defects pertaining to this age group are primarily diagnosed by imaging. Electrophysiological studies are believed to play a role in the risk-stratification of BrS but the findings from various studies are not confirmatory and its role is still arguable.39

5.5. Clinical scoring systems

Clinical criteria incorporating family history, nature of symptoms and ECG characteristics are normally used in the initial evaluation of patients presenting with evidence of LQTS. Based on the revised Schwartz criteria of 2011, ≤1 point indicates low probability of LQTS, 1.5 to 3 points indicates intermediate probability of LQTS, and ≥3.5 points indicates high probability of LQTS.40 For patients with suspected SQTS, the Gollob score could be a useful tool to facilitate evaluation.41

5.6. Genetic testing for channelopathies

The evolution of genetic testing into a clinical diagnostic tool has undoubtedly revolutionized the management of patients with inherited arrhythmia syndromes. Advances in DNA sequencing technology, namely next generation sequencing platforms, have paved the way for rapid, reliable and relatively less expensive genetic diagnostics and have also made possible whole exome and whole genome sequencing whereby previously undescribed genetic variants are being identified in the causation of SCD.

While the pathogenetics of various human diseases are beginning to unfold, LQTS is one disease where impact of genetics is felt in at least three different areas: diagnosis, risk-stratification and treatment.7 Genetic testing has significantly altered the dynamics of diagnosing LQTS, especially in patients with a nondiagnostic QTc where clinical scoring loses efficacy. In addition to the genotype–phenotype correlations that have emerged from genetic testing of large cohorts of LQTS patients from the International LQTS registry and a few nationwide registries, an abundance of information has become available on the location, type, and biophysical function of mutations as independent risk factors influencing the clinical course of the disorder. Age, gender, QTc, nature of genetic mutation, and response to beta-blocker therapy, are the five major determinants of risk of SCD in an individual with LQTS.42 While LQT1 males are at increased risk for cardiac events in childhood in particular, LQT2 females, probably due to sensitivity to changes in sex hormones, experience events mainly after the onset of adolescence or menopause and in the postpartum period. Occurrence of a cardiac event in the first year of life leaves the patient at a very high risk of subsequent SCA/SCD during the next 10 years of life. QTc >500 ms is a powerful indicator of risk; however, a quarter of LQTS mutation carriers have a normal range QTc but still exhibit a greater than 10-fold increase in life-threatening events compared to unaffected family members.43 Combined assessment of clinical and mutation specific data, such as their site of occurrence in the ion channels, has recently been identified as relevant in the risk stratification of LQTS. Patients, particularly women, with intracellular cytoplasmic loop (C-loop) missense mutations in the KCNQ1 gene exhibit a high risk for life-threatening events, whereas among LQT2 patients, men with pore-loop KCNH2 mutations are more prone to SCA/SCD.44

A patient with a robust clinical diagnosis of LQTS has a 75% chance that a mutation will be found in one of the disease-causing genes. However, genetic testing is still a time and cost consuming tool and should not be applied without appropriate phenotype evaluation and validation. It is imperative that readily available tools like clinical scoring, ECG, exercise stress test and Holter monitoring are effectively utilised to assess the need for genotyping in all probands, as well as in asymptomatic relatives of affected patients. As with any clinical test, understanding the spectrum of background noise within a given genetic test is critical to interpreting the test results. Specifically, systematic evaluation of a genetic test's “signal-to-noise” ratio is crucial to determine whether a previously unidentified variant might be the biomarker responsible for disease or whether it is a rare genetic variant with no relevance to the disease in question.45

For patients with BrS, genetic testing helps in confirming the diagnosis but hardly plays any role in risk stratification and treatment. The nature of the mutation, however, has been proposed to be a predictor of disease severity.46 The significance of obtaining a genetic diagnosis of loss-of-function sodium channelopathies in preventing sudden death among the younger relatives of affected probands has been documented beyond doubt. In case of a clinical suspicion of CPVT, genotyping for the RYR2 and CASQ2 mutations not only has a high yield but also helps to initiate treatment in the proband and the disease carrying family members in a timely manner and to reduce mortality due to this highly lethal disease.

In a family that is bereaving the unexpected death of a young relative, post-mortem genetic testing of the stored blood sample is the only way of identifying a channelopathic cause of death and it also provides a lead for evaluating family members. In case a sample is unavailable, the first-degree relatives are interrogated and examined for any clues to a possible cause. As most countries screen newborns for genetic conditions with a Guthrie test, it could also serve as a source of DNA to perform postmortem genetic testing. However, as heelprick samples are not routinely stored long-term, their retrieval at a later stage is not always feasible. Comprehensive cardiac and genetic examination of relatives of young resuscitated SCD victims has a diagnostic yield as high as 60%.47

The role of genetic counselling in the management of patients and families cannot be overemphasized. It is the lynchpin in obtaining a thorough family history, in providing the pertinent information to the patients regarding the disease in question and in ensuring that both the proband and the family members have a good understanding of what to expect from a genetic test. An experienced counsellor also talks to the affected persons about what could be the long-term implications in the health front as well as in other areas like insurability, employment and having a family of their own for young adults.4

6. Treatment strategies in channelopathies

The treatment modalities employed can be largely grouped into general preventive measures, specific lifestyle modifications, pharmacotherapy, device therapy and surgical interventions. Counselling patients and parents about avoiding drugs that are known to trigger arrhythmias (QT-prolonging drugs and drugs to avoid in BrS), about aggressive fever management in young children, about avoidance of competitive sports in case of LQT1 and CPVT, and avoidance of loud alarms and doorbells for LQT2 patients are some strategies used to prevent arrhythmias. Potassium supplementation has been proven to help control arrhythmias in LQT2 patients.

β-Blockers are the mainstay in the pharmacotherapy of LQTS and CPVT. They represent the first choice therapy in symptomatic LQTS patients, unless specific contraindications exist. The impairment in the IKs current makes LQT1 patients particularly sensitive to catecholamines and quite responsive to β-blockade; so they seldom need more than antiadrenergic therapy. Although β-blockers are the first-line treatment in LQT2 and LQT3 patients as well, their risk of cardiac events while receiving therapy (i.e. breakthrough cardiac events, BCE), is higher than in LQT1 patients. The occurrence of BCE has largely been attributed to a high-risk status prior to start of therapy, noncompliance and use of other QT-prolonging drugs. Suspicion that not all β-blockers offer equivalent protection in LQTS has been confirmed by a recent study showing that propranolol and nadolol are the preferred choice of β-blockers in symptomatic LQT1 and LQT2 patients.48 Pharmacological management of LQT3 has remained a challenge particularly due to its high-risk profile and the relative paucity of literature (which is closely associated with the low disease prevalence). A large multicentre study on nearly 400 LQT3 patients supports the belief that β-blockers are generally extremely effective in treating those LQT3 patients who do not have cardiac events in the first year of life.49

The cornerstone in the treatment of affected CPVT patients, both symptomatic and asymptomatic, are β-blockers. Most symptomatic patients become symptom-free with an adequate dosage of β-blockers but should be counselled about the potentially lethal implications of drug noncompliance. The second line of therapy in patients with an inadequate response to β-blockers is flecainide, a class 1c antiarrhythmic agent, which is usually added to the β-blocker treatment. Device therapy and surgical denervation are reserved for the high-risk cases where medical management is ineffective or poorly tolerated.4 Quinidine, mexiletine and ranolazine are the other drugs showing some promise in controlling the inherited arrhythmias.4

Device therapy with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) aborts the ventricular arrhythmias that arise in affected patients while surgical left cardiac sympathetic denervation (LCSD) inhibits the adrenergic overdrive mediated electrical instability of the heart. In LQTS and CPVT, both these therapies are reserved for patients with symptoms despite β-blockers and the survivors of SCA.4 β-Blocker therapy is normally continued with the adjunctive therapy, unless contraindicated. When syncope recurs despite full dose β-blockers, LCSD should be considered first and implemented if possible. Surgical LCSD has also been used successfully in some LQT3 patients. ICD therapy, though life-saving in many instances, has the inherent drawback of inappropriate shocks, mechanical failures, and poor psychological impact, leading to major setbacks in patients of all ages, more so in the pediatric population. In BrS patients with a high risk of SCD, the lack of an ideal pharmacological agent makes ICD the only proven tool to prevent fatalities.

Prophylactic treatment in genotype-positive individuals who have a high possibility of developing arrhythmias is one of the major advantages of cascade screening of family members of affected probands. ECG markers, age at diagnosis and genotype should help guide decision to treat in asymptomatic patients. It should be remembered that drug compliance could be an issue in this population, particularly since a good proportion of affected patients are in their adolescence and would require age-appropriate counselling.

7. The India perspective

With the mind-boggling developments in our understanding of the genotype–phenotype correlations and the management of patients with channelopathies, the fact that there is a large lacuna in this field of medicine in India cannot be disputed. The scope for systematic genetic analyses of cases with a suspicious phenotype is huge given that even rare conditions can affect a large number of people in a highly populated country like India. Moreover, due to the unique genetic variation of the Indian subcontinent,50 western genetic data cannot be simply extrapolated to the local population but we will have to build a database of our own. Knowing that simple (and economical) pharmacotherapy together with specific lifestyle changes is all that is required to prevent sudden death in most of the affected children and young adults, the case for genotyping of all index patients and cascade screening of families is very strong.

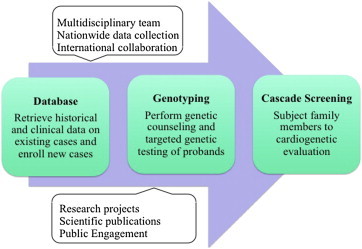

The way forward is summarized in Fig. 5. There are a few things that have to go hand in hand to be able to achieve this. First, initiation of programs to spread awareness among general practitioners, pediatricians and neurologists and steps to incorporate teaching on the genetics of SCD in medical schools. Second, collaborative efforts among the cardiology teams in various healthcare settings should allow for a database to be constructed. Third, the establishment of multidisciplinary inherited heart disease clinics should pave the way for systematic care and counselling of affected patients and their families.

Fig. 5.

Flowchart for necessary action to establish a comprehensive approach to clinical and genetic evaluation of patients with inherited arrhythmias in India.

In conclusion, inherited arrhythmias are a complex set of potentially lethal diseases, the management of which includes a thorough cardiologic evaluation, systematic genetic diagnostics and effective therapeutic measures. The wealth of knowledge that has become available to us from the various registries of the western world should encourage a unanimous national effort to better characterize and control these diseases in the Indian population.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Ackerman M.J. Cardiac channelopathies: it's in the genes. Nat Med. 2004;10:463–464. doi: 10.1038/nm0504-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bezzina C.R., Barc J., Mizusawa Y. Common variants at SCN5A-SCN10A and HEY2 are associated with Brugada syndrome, a rare disease with high risk of sudden cardiac death. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1044–1049. doi: 10.1038/ng.2712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cirino A.L., Ho C.Y. Genetic testing for inherited heart disease. Circulation. 2013;128:e4–e8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Priori S.G., Wilde A.A., Horie M. Executive summary: HRS/EHRA/APHRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of patients with inherited primary arrhythmia syndromes. Europace. 2013;15:1389–1406. doi: 10.1093/europace/eut272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trachtenberg F.L., Haas E.A., Kinney H.C. Risk factor changes for sudden infant death syndrome after initiation of Back-to-Sleep campaign. Pediatrics. 2012;129:630–638. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tester D.J., Ackerman M.J. The role of molecular autopsy in unexplained sudden cardiac death. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2006;21:166–172. doi: 10.1097/01.hco.0000221576.33501.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ackerman M.J., Priori S.G., Willems S. HRS/EHRA expert consensus statement on the state of genetic testing for the channelopathies and cardiomyopathies this document was developed as a partnership between the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) and the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) Europace. 2011 Aug;13(8):1077–1109. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klaver E.C., Versluijs G.M., Wilders R. Cardiac ion channel mutations in the sudden infant death syndrome. Int J Cardiol. 2011;152:162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilde A.A., Behr E.R. Genetic testing for inherited cardiac disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10:571–583. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz P.J., Periti M., Malliani A. The long Q-T syndrome. Am Heart J. 1975;89:378–390. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(75)90089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwartz P.J., Stramba-Badiale M., Crotti L. Prevalence of the congenital long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2009;120:1761–1767. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.863209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Priori S.G., Napolitano C., Schwartz P.J. Low penetrance in the long-QT syndrome: clinical impact. Circulation. 1999;99:529–533. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.4.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwartz P.J., Ackerman M.J., George A.L., Jr. Impact of genetics on the clinical management of channelopathies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:169–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giudicessi J.R., Ackerman M.J. Potassium-channel mutations and cardiac arrhythmias–diagnosis and therapy. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012;9:319–332. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chockalingam P., Wilde A. The multifaceted cardiac sodium channel and its clinical implications. Heart. 2012;98:1318–1324. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-301784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winbo A., Stattin E.L., Diamant U.B. Prevalence, mutation spectrum, and cardiac phenotype of the Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome in Sweden. Europace. 2012;14:1799–1806. doi: 10.1093/europace/eus111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goyal J.P., Sethi A., Shah V.B. Jervell and Lange-Nielson syndrome masquerading as intractable epilepsy. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2012;15:145–147. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.95003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crotti L., Johnson C.N., Graf E. Calmodulin mutations associated with recurrent cardiac arrest in infants. Circulation. 2013;127:1009–1017. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.001216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crotti L., Monti M.C., Insolia R. NOS1AP is a genetic modifier of the long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2009;120:1657–1663. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.879643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amin A.S., Giudicessi J.R., Tijsen A.J. Variants in the 3' untranslated region of the KCNQ1-encoded Kv7.1 potassium channel modify disease severity in patients with type 1 long QT syndrome in an allele-specific manner. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:714–723. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilde A.A., Coronel R. The complexity of genotype-phenotype relations associated with loss-of-function sodium channel mutations and the role of in silico studies. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H8–H9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00494.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li A., Saba M.M., Behr E.R. Genetic biomarkers in Brugada syndrome. Biomark Med. 2013;7:535–546. doi: 10.2217/bmm.13.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Probst V., Denjoy I., Meregalli P.G. Clinical aspects and prognosis of Brugada syndrome in children. Circulation. 2007;115:2042–2048. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.664219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanter R.J., Pfeiffer R., Hu D. Brugada-like syndrome in infancy presenting with rapid ventricular tachycardia and intraventricular conduction delay. Circulation. 2012;125:14–22. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.054007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chockalingam P., Clur S.A., Breur J.M. The diagnostic and therapeutic aspects of loss-of-function cardiac sodium channelopathies in children. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:1986–1992. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chockalingam P., Rammeloo L.A., Postema P.G. Fever-induced life-threatening arrhythmias in children harboring an SCN5A mutation. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e239–e244. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leenhardt A., Lucet V., Denjoy I. Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in children. A 7-year follow-up of 21 patients. Circulation. 1995;91:1512–1519. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.5.1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Viskin S., Belhassen B. Idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Am Heart J. 1990;120:661–671. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(90)90025-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haïssaguerre M., Derval N., Sacher F. Sudden cardiac arrest associated with early repolarization. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2016–2023. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watanabe H., Nogami A., Ohkubo K. Electrocardiographic characteristics and SCN5A mutations in idiopathic ventricular fibrillation associated with early repolarization. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4:874–881. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.963983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Postema P.G., Christiaans I., Hofman N. Founder mutations in the Netherlands: familial idiopathic ventricular fibrillation and DPP6. Neth Heart J. 2011;19:290–296. doi: 10.1007/s12471-011-0102-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barsheshet A., Goldenberg I. Cardiovascular syncope: diagnostic approach and risk assessment. Minerva Medicoleg. 2011;102:223–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moss A.J., Robinson J.L., Gessman L. Comparison of clinical and genetic variables of cardiac events associated with loud noise versus swimming among subjects with the long QT syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84:876–879. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00458-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilde A.A., Jongbloed R.J., Doevendans P.A. Auditory stimuli as a trigger for arrhythmic events differentiate HERG-related (LQTS2) patients from KVLQT1-related patients (LQTS1) J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:327–332. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00578-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colman N., Bakker A., Linzer M. Value of history-taking in syncope patients: in whom to suspect long QT syndrome? Europace. 2009;11:937–943. doi: 10.1093/europace/eup101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Postema P.G., De Jong J.S., Van der Bilt I.A. Accurate electrocardiographic assessment of the QT interval: teach the tangent. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:1015–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sy R.W., van der Werf C., Chattha I.S. Derivation and validation of a simple exercise-based algorithm for prediction of genetic testing in relatives of LQTS probands. Circulation. 2011;124:2187–2194. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.028258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Viskin S., Postema P.G., Bhuiyan Z.A. The response of the QT interval to the brief tachycardia provoked by standing: a bedside test for diagnosing long QT syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1955–1961. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mizusawa Y., Wilde A.A. Brugada syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012;5:606–616. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.964577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwartz P.J., Crotti L. QTc behavior during exercise and genetic testing for the long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2011;124:2181–2184. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.062182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gollob M.H., Redpath C.J., Roberts J.D. The short QT syndrome: proposed diagnostic criteria. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:802–812. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Priori S.G., Schwartz P.J., Napolitano C. Risk stratification in the long-QT syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1866–1874. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goldenberg I., Horr S., Moss A.J. Risk for life-threatening cardiac events in patients with genotype-confirmed long-QT syndrome and normal-range corrected QT intervals. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Migdalovich D., Moss A.J., Lopes C.M. Mutation and gender-specific risk in type 2 long QT syndrome: implications for risk stratification for life-threatening cardiac events in patients with long QT syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:1537–1543. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.03.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kapa S., Tester D.J., Salisbury B.A. Genetic testing for long-QT syndrome: distinguishing pathogenic mutations from benign variants. Circulation. 2009;120:1752–1760. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.863076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meregalli P.G., Tan H.L., Probst V. Type of SCN5A mutation determines clinical severity and degree of conduction slowing in loss-of-function sodium channelopathies. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:341–348. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van der Werf C., Hofman N., Tan H.L. Diagnostic yield in sudden unexplained death and aborted cardiac arrest in the young: the experience of a tertiary referral center in The Netherlands. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:1383–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chockalingam P., Crotti L., Girardengo G. Not all beta-blockers are equal in the management of long QT syndrome types 1 and 2: higher recurrence of events under metoprolol. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2092–2099. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilde A.A., Kaufman E.S., Shimizu W. Sodium channel mutations, risk of cardiac events, and efficacy of beta-blocker therapy in type 3 long QT syndrome (abstr) Heart Rhythm. 2012;9(suppl l):S321. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tamang R., Singh L., Thangaraj K. Complex genetic origin of Indian populations and its implications. J Biosci. 2012;37:911–919. doi: 10.1007/s12038-012-9256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]