Abstract

Background

Modulation of γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptors (GABAARs) by general anesthetics may contribute to their ability to produce amnesia. Receptors containing α5 subunits, which mediate tonic and slow synaptic inhibition, are co-localized with β3 and γ2 subunits in dendritic layers of the hippocampus and are sensitive to low (amnestic) concentrations of anesthetics. Since α5 and β3 subunits influence performance in hippocampus-dependent learning tasks in the presence and absence of general anesthetics, and the experimental inhaled drug 1,2-dichlorohexafluorocyclobutane (F6) impairs hippocampus-dependent learning, we hypothesized that F6 would modulate receptors that incorporate α5 and β3 subunits. We hypothesized further that the β3(N265M) mutation, which controls receptor modulation by general anesthetics, would similarly influence modulation by F6.

Methods

Using whole-cell electrophysiological recording techniques, we tested the effects of F6 at concentrations ranging from 4 μM to 16 μM on receptors expressed in human embryonic kidney293 cells. We measured drug modulation of wild type α5β3 and α5β3γ2L GABAARs, and receptors harboring the β3(N265M) mutation. We also tested the effects of F6 on α1β2γ2L receptors, which were reported previously to be insensitive to this drug when expressed in Xenopus oocytes.

Results

F6 enhanced the responses of wild type α5β3γ2L but not α1β2γ2L receptors to low concentrations of GABA in a concentration-dependent manner. Receptors that incorporated the mutant β3(N265M) subunit were insensitive to F6. When applied together with a high concentration of GABA, F6 blocked currents through α5β3 but not α5β3γ2L receptors. F6 did not alter deactivation of α5β3γ2L receptors after brief, high concentration pulses of GABA.

Conclusions

The nonimmobilizer F6 modulates GABAARs in a manner that depends on subunit composition and on mode of receptor activation by GABA, supporting a possible role for α5-containing receptors in suppression of learning and memory by F6. Furthermore, common structural requirements indicate that similar molecular mechanisms may be responsible for the enhancing effects of F6 and conventional general anesthetics.

Introduction

The ionotropic γamma-aminobutyric acid receptor (GABAAR) is a target of considerable interest for the mechanism of action of general anesthetics.1 The precise roles that GABAergic mechanisms play in bringing about the various endpoints of the clinical anesthetic state (sedation, amnesia, loss of consciousness and immobility in response to a noxious stimulus) remain, however, largely undefined for inhaled drugs.2

One “pharmacological tool” introduced into the experimental paradigm to bridge the gap between receptors and behavior is a group of compounds termed “nonimmobilizers.” These drugs, despite being predicted to act as anesthetics by their lipid solubility, lack many of the behavioral effects of anesthetics, including the ability to prevent movement in response to a noxious stimulus at predicted concentrations,i.e., they disobey the “Meyer-Overton rule.”3 However, they do possess some anesthetic properties, such as the capacity to produce amnesia, with impairment of hippocampus-dependent learning occurring at a fraction of the predicted immobilizing concentration.4 Another strategy uses point mutations that alter or eliminate the responsiveness of specific receptors and ion channels to various general anesthetic drugs.1 Specifically, point mutations in the transmembrane (TM) regions of the α and β subunits in recombinant GABAARs have been described that reduce or eliminate positive modulation of the receptors by some general anesthetics.5–7 One of these mutations, replacement of the asparagine residue with methionine in position 265 in TM2 of the β3 subunit (N265M), when expressed as α2β3(N265Mγ2, leads to GABAARs that are substantially less sensitive to modulation by the IV anesthetic etomidate and by the inhaled drug enflurane.8,9 Its impact on nonimmobilizers remains unknown.

We combined these 2 approaches and tested whether the nonimmobilizer 1,2-dichlorohexafluorocyclobutane (F6, also referred to in the literature as 2N) modulates α5-containing receptors, and whether the β3(N265M) mutation affects that modulation. We chose the α5β3γ2L subunit combination because the β3 subunit is highly co-localized with the α5 subunit in the dendritic layers of the hippocampus,10 the β3 subunit has been linked to memory impairment by isoflurane,11 and several in vivo studies have shown that α5-containing receptors influence hippocampus-dependent learning,12–15 possibly by modulating the threshold for induction of long-term enhancement.16 We found that F6, at concentrations ranging from 4 to 16 μM,17 did indeed enhanceα5β3γ2L receptors activated by a low concentration of GABA in a concentration-dependent manner, and that the β3(N265M) mutation prevented this enhancement. However, unlike conventional anesthetics, which typically prolong current decay, F6 did not alter deactivation of α5β3γ2L receptors after brief, high concentration pulses of GABA. We conclude that there are common structural requirements, but different kinetic mechanisms, for the enhancing effects of the nonimmobilizer F6 and volatile anesthetics, and that enhancement of specific types of GABAA receptorR-mediated inhibition may underlie their amnestic effects.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Receptor Expression

Cell culture materials were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) unless stated otherwise. Transformed human embryonic kidney 293 cells purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) were cultured under standard conditions in minimum essential medium with L-glutamine supplemented with minimum essential medium amino acids solution (0.1 mM), sodium pyruvate (1 mM), 1% streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum on 12-mm glass coverslips in 60 × 15 mm dishes. Cells were transiently transfected with α5β3 (1:1), α5β3γ2L (1:1:5), α5β3(N265M)γ2L (1:1:5), or α1β2γ2L (1:1:5) subunits individually inserted in the mammalian expression vector pCEP4 (Invitrogen) and enhanced green fluorescence protein using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). After incubating for 6 hours, the culture medium was replaced with supplemented minimum essential medium. Cells were used for electrophysiological recordings 24–48 hours after transfection.

Electrophysiological Recordings

Coverslips with transfected cells were transferred to a culture dish filled with HEPES-buffered extracellular solution containing (mM): 130 NaCl, 3.1 KCl, 10.9 Na-HEPES, 1.44 MgCl2, and 2.17 CaCl2, pH = 7.3. Recording pipettes were filled with (mM): 140 CsCl, 10 Na-HEPES, 10 EGTA, and 2 MgATP. For concentration-response experiments with F6, the extracellular solution contained (mM): NaCl 145, KCl 5, MgCl2 1, CaCl2 1.8 HEPES 10; pH 7.4, and recording pipettes were filled with (mM): 130 KCl, 10 Na-HEPES, 1 MgCl2, 5 EGTA, and 5 MgATP.

Electrophysiological recordings were performed on the stage of a Nikon inverted microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Tokyo, Japan) with Hoffman-modulated optics. Glass pipettes were prepared from borosilicate glass (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT, or Garner Glass Company, Claremont, CA) with a multistage puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) and fire polished. Open tip resistances were typically 2–5 MΩ. Cells were visualized using a mercury arc lamp and an enhanced green fluorescence protein filter set. Data were acquired using equipment from Axon Instruments (now a division of Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Currents were recorded with the whole-cell configuration of the patch clamp technique using an Axopatch 200B amplifier, sampled at 10kHz (Digidata 1200 AD converter), filtered at 1kHz (-3dB, four-pole Bessel) and stored on an IBM-compatible computer running pCLAMP 9 software.

Solution Application

Extracellular saline and test solutions containing GABA (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and/or F6 (Lancaster Synthesis Inc., Pelham, NH) were transiently applied to fluorescing whole cells lifted from the coverslip and placed before flowing streams of extracellular solutionusing 3 different methods. (1) For rapid (~3ms) solution exchanges between limited numbers of solutions, we used a gravity-fed 2-barrel theta application pipette connected to solution reservoirs using polyimide and Teflon™ (DuPont, Wilmington, DE) tubing, and mounted to a stacked piezoelectric translator (Physik Instrumente, Irvine, CA); (2) for slower (~30ms) solution exchanges between larger numbers of nonvolatile solutions, we used a 16-channel Dynaflow pressurized microfluidic chip (DF-16, Cellectricon, Gaithersburg, MD) with open reservoirs; (3) for solution exchanges (~30ms) between larger numbers of solutions that included the volatile compound F6, we used a custom-fabricated multibarrel application device consisting of Teflon™ and polyimide tubing connected to closed gravity-fed Teflon™ solution reservoirs. Test solutions were applied by delivering a filtered (100 Hz, filter model 902 LFP; Frequency Devices, Haverhill, MA) voltage pulse to a high voltage amplifier (model P-270, Physik Instrumente, Auburn, MA) that drove a translator to which the theta-pipette was mounted (method 1), or using a stepper motor-based microscope translation stage (Corvus, iTK, Dr. Kassen, GmbH, Germany) (method 2). Solution exchange rates were estimated using the open tip junction potential method.18

Test solution pulses (20 ms or 2 sec) were applied at a frequency that prevented accumulation of desensitization, manifested as a decline in peak current amplitudes triggered by saturating concentrations of GABA (1–3 mM) of less than 5% (data not shown). Concentration-response relationships for α5β3 and α5β3γ2L receptors were constructed by delivering a range of GABA solutions (0.01 μM – 3 mM) to single cells using a series of low volume manually controlled Teflon™ (DuPont, USA) valves. For α5β3(N265M)γ2L and α1β2γ2L receptors this was accomplished using the Dynaflow df-16 chip. Deactivation kinetics were assessed by applying 20 ms pulses of 1 mM GABA in the absence or continuous presence of F6.

Solutions were prepared as described previously.17,19 Briefly, GABA-containing solutions were prepared from a freshly made stock solution. F6-containing solutions were made using F6-saturated air as a “stock,” added to the experimental solution in gas-tight Chemware Teflon FEP gas sampling bags (North Safety Products, Cranston, RI). The targeted concentrations of F6 ranged from 4 μM to 16 μM. (An aqueous concentration of 16 μM corresponds to the predicted minimum alveolar concentration (MACpred) that would inhibit movement in response to a noxious stimulus if F6 were to obey the Meyer-Overton rule17). Concentrations of F6 were confirmed using a Varian 3700 gas chromatograph (Varian Inc., Walnut Creek, CA) equipped with a flame ionization detector and a 80/100 Poropak Q packed stainless steel column. Measured concentrations were all within ~5% of targeted concentrations.

Data Analysis

Whole cell currents were analyzed using Origin 6.1 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA) and Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). For generation of concentration-response relationships, peak currents were measured relative to baseline and normalized to the peak current evoked by a saturating concentration (1–3 mM) of GABA, and plotted as a function of agonist concentration. Curves were fitted to the equation I = 1 − [1 + ([GABA]/EC50)n]−1, where EC50 is a concentration that yields a half-maximal response, and n is the slope coefficient of the sigmoidal fit. Current deactivation triggered by 20 ms pulses of 1 mM GABA was fit by exponential functions beginning shortly after the peak of the response using a Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm. During the fitting process, the goodness of fit was evaluated by the χ2 value, and adequacy of fit to triexponential functions was judged by eye. To generate a single time constant for comparison between control and F6 deactivation responses, a weighted time constant (τw) was calculated according to the equation τw = (ΣτiAi/ΣAi), where τi and Ai are the time constant and amplitude of the individual exponential components.

Results are presented as mean ± S.D. or S.E.M. as indicated. The numbers of observations (n=) reflect the number cells tested under a specific combination of conditions, such as the receptor subunit combination that was expressed, the concentration of GABA that was used to activate the receptors, and the concentration of F6 that was applied. Since only 1 excised patch was obtained from any individual cell, this number applies to experiments using rapid solution exchange with excised patches as well as slower solution exchange with whole-cell recordings. For the concentration-response studies for F6 using slow solution exchange, each cell was exposed to all concentrations. For other experiments, each cell was exposed to only a single concentration of GABA as indicated, as well as a saturating concentration to permit normalization. The number of observations obtained for each experimental dataset was based on prior experience with similar types of experiments, together with an ongoing qualitative assessment of electrophysiologic responses; once a consistent effect (or lack of effect) under a specific set of conditions was evident, a formal statistical evaluation of the dataset or a representative subset (e.g.,1 specific concentration of GABA in a concentration-response series) was performed. Unpaired t-tests were used to test for differences between mean values; statistical significance was evaluated using p < 0.005.

Results

Effects on α5β3 receptors

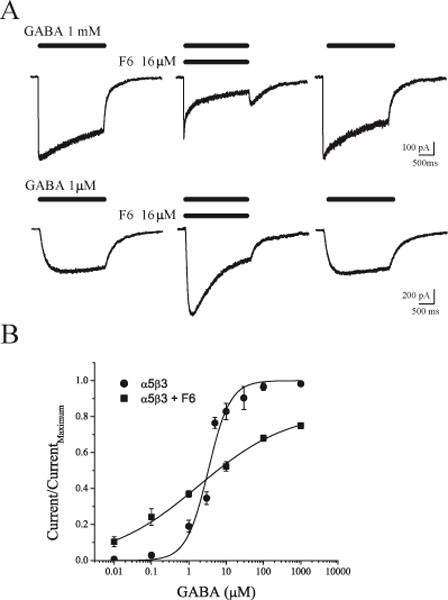

Using rapid (~3ms) solution exchange methods, we tested the effects of F6 on responses of α5β3 receptors activated by saturating concentrations of GABA (1 mM), and on receptors activated by a lower concentration of GABA (1 μM). An example of the response from an individual cell is shown in Figure 1. Co-application of F6 and 1 mM GABA resulted in inhibition of peak currents and the emergence of a rebound current after drug washout (Figure 1A, top). This finding is similar to our previous results obtained using α1β2 receptors and F6.19 However, when receptors were activated by 1 μM GABA, F6 enhanced peak currents (Figure 1A, bottom). The results of a series of experiments using a range of GABA concentrations are summarized in Figure 1B. The effects of 1 MACpred F6 ranged from enhancement of the responses to low concentrations of GABA (+96 ± 11% at 1 μM, p=0.003) to inhibition at high concentrations (−24 ±4%, vs. control at 1 mM, p<0.0001).

Figure 1.

Differential effects of F6 on heterodimeric α5β3 GABAA receptors. A. Responses to a two-second-long application of 1 mM GABA (top) and of 1 μM GABA (bottom). Middle traces were obtained during co-application of GABA and 16 μM F6. B. Concentration-response relationships for α5β3 GABAA receptors in the absence (circles, EC50 = 3.3 μM, slope = 1.48, n = 3–9) and presence (squares, EC50 = 1.83 μM, slope = 0.36, n = 4–6) of F6 (mean ± S.E.M).

Effects on α5β3γ2L receptors

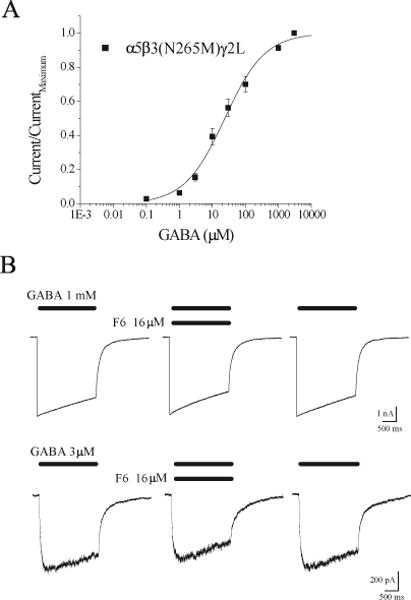

We also examined the effects of F6 on responses of heterotrimeric α5β3γ2L receptors activated by low and high concentrations of GABA. An example of1 such experiment is shown in Figure 2. In contrast to its effects on heterodimeric receptors, F6 did not block responses to 1 mM GABA (Figure 2A, top traces). Responses to low concentrations of GABA were, however, still markedly enhanced by F6 (Figure 2A, bottom trace). A summary of the results obtained with α5β3γ2L receptors is shown in Figure 2B. On average, F6 increased the responses of receptors activated by 1 μM GABA from 14 ± 2% (n=12) to 35 ±5% (n=8) of the maximal response (p=0.0002). The leftward shift in the GABA concentration-response relationship indicates that F6 either increased the affinity of GABA for its site or increased the efficacy of GABA to open the channel.

Figure 2.

Differential effects of F6 on heterotrimeric α5β3γ2L GABAA receptors. A. In contrast to its inhibition of heterodimeric receptors, 16 μM F6 (middle trace) did not block responses to 1 mM GABA (top), but it did enhance responses to 1 μM GABA (bottom) mediated by heterotrimeric receptors B. Concentration response relationships for α5β3γ2L receptors in the absence (squares, EC50 = 10.8 μM, slope = 0.68, n = 5–13) and presence (circles, EC50 = 4.7 μM, slope = 0.45, n = 3–8) of F6 (mean ± S.E.M). C. F6 had no effect on the time course of desensitization or deactivation. Normalized whole cell responses to 20 ms pulses of 1 mM GABA in the absence and continuous presence of F6 (16 μM).

Kinetic analysis

To help define the possible kinetic mechanisms by which F6 enhanced subsaturating responses of heterotrimeric channels, we analyzed deactivation trajectories for α5β3γ2L receptors triggered to open by 20 ms pulses of 1 mM GABA in the absence and the continuous presence of F6 (Figure 2C). Unlike conventional anesthetics, which typically prolong current decay,2 F6 failed to alter deactivation (τwt F6/control = 105 ± 5.2%, n=14, p=0.70). This observation indicates that the molecular mechanisms by which F6 and conventional anesthetics modulate GABAARs differ, and it places limits on the possible kinetic mechanisms by which F6 might enhance low concentration responses (Discussion below contains more detail).

Effects on mutant receptors

To test whether the enhancement of responses to low GABA concentrations by F6 shares structural requirements with other volatile drugs, we tested whether a mutation at the N265 position of the β3 subunit that interferes with positive receptor modulation by enflurane8,9 also influences modulation by F6. In order to compare equi-effective concentrations in the wild type and mutant receptors, we first established a GABA concentration-response relationship for α5β3(N265M)γ2L subunit-containing GABAARs (Figure 3A). The mutant heterotrimeric receptor displayed a nearly 2-fold higher EC50 for GABA compared to wild type receptors (compare with Figure 2B), consistent with previous results using α2β3γ2 receptors.8 An example of the effect of F6 on these mutant receptors is shown in Figure 3B. Similar to its effect on wild 3type receptors, F6 had no effect on the peak amplitude of responses triggered by 1 mM GABA (Figure 3B, upper traces). Most remarkably, however, F6 failed to enhance the responses of mutant receptors to 3 μM GABA (~EC20) (Figure 3B, bottom traces). On average, whereas F6 enhanced EC20 responses from wild type receptors by 310 ± 215% (1 μM GABA, p=0.0015, n=5), mutant receptors may have been blocked by 21.7 ± 8.6% (3 μM GABA, p=0.0095, n=5). These data indicate that the N265 position is critical for the enhancing effect of F6 on GABA-activated receptors, as it is for the volatile anesthetic enflurane acting on α2β3γ2 GABAARs.8

Figure 3.

The β3 N265M mutation prevents potentiation by F6. A. Concentration-response relationship. The mutant α5β3(N265M)γ2L receptors are less sensitive to GABA than the wild type (EC50 = 23.6 μM, slope = 0.71, n = 8) (mean ± S.E.M). B. In contrast to the wild type, F6 failed to enhance responses to 3 μM GABA (EC20, bottom), and slightly reduced responses to 1 mM GABA (top).

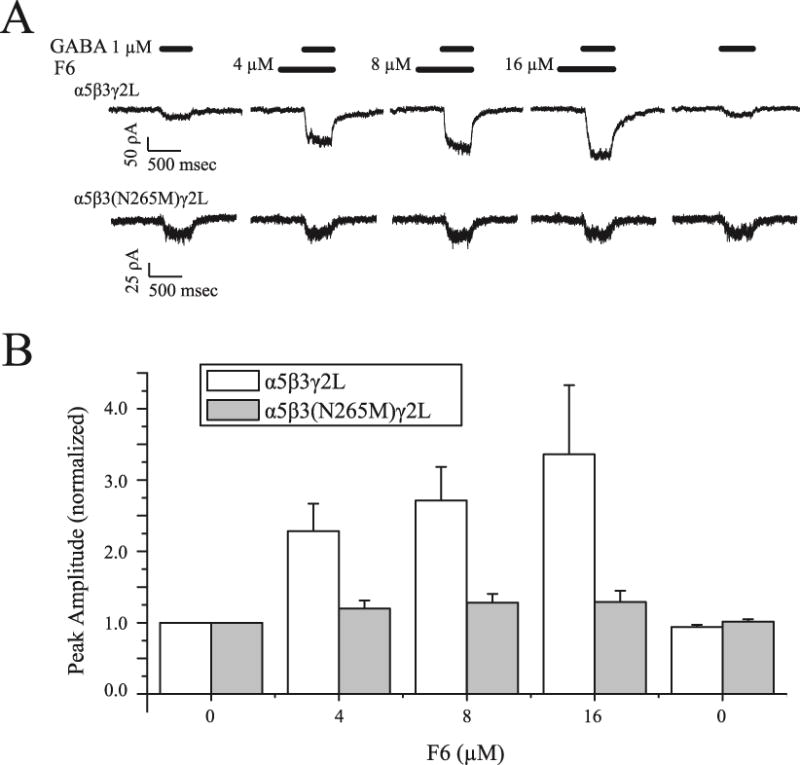

Concentration dependence of modulation

Using slower (~30 ms) solution exchange methods, we tested the concentration dependence of F6 modulation of α5β3γ2L and α5β3(N265M)γ2L receptors. An example of 1 such experiment is shown in Figure 4A. At concentrations ranging from 4 to 16 μM, F6 enhanced responses to 1 μM GABA in a concentration-dependent manner for α5β3γ2L receptors, but there was little or no enhancement of α5β3(N265M)γ2L receptors. A summary of effects at different concentrations is presented in Figure 4B. On average, responses of wild type receptors to 1 μM GABA in the presence of 8 μM F6 (the EC50 concentration for suppressing fear conditioning to context4) were 2.7 ± 0.47 times larger than in the absence of F6 (p=0.0003, n=5), but mutant receptors responses were not significantly larger (1.3 ± 0.12 times, p=0.02, n=5). This strong enhancement of low GABA concentration responses by a low concentration of F6 is consistent with a role for α5-containing receptors that mediate tonic or slow phasic inhibition triggered by ambient GABA or spillover from nearby synapses20 in memory impairment.

Figure 4.

F6 modulates α5β3γ2L but not α5β3(N265M)γ2L receptors at amnestic concentrations. A. Responses to a 500 ms-long application of 1 μM GABA to α5β3γ2L receptors (top) and to α5β3(N265M)γ2L receptors (bottom). B. Concentration-response relationships for α5β3γ2L and α5β3(N265M)γ2L receptors in the presence of F6 ranging from 4 to 16 μM, normalized to the peak amplitude under control conditions (absence of F6).

Effects on α1β2γ2L receptors

We showed previously that F6 neither blocks nor alters deactivation of α1β2γ2s receptors activated by brief pulses of a high concentration of GABA,19 similar to our present results with α5β3γ2L receptors. However, in our previous study we did not test responses to subsaturating GABA concentrations. To test whether F6 enhances responses of α1β2γ2L receptors activated by a low concentration of GABA, we measured peak currents triggered by 1 μM GABA in the absence and presence of F6. At concentrations up to 16 μM, F6 failed to enhance the responses of α1β2γ2L receptors (8 μM 90±7%, p=0.20; 16 μM 99 ± 10%, p=0.99; n=5 for both). Thus, enhancement of low concentration GABA responses by F6 is subunit-specific.

Discussion

We have combined 2 experimental strategies recently introduced to anesthetic research: F6, which is the best-studied representative of the nonimmobilizer class of drugs, and the N265M point mutation of the GABAARβ3 subunit, which conveys resistance to both IV and inhaled anesthetic modulation in vitro8 and in vivo.21 Together, they have allowed us to address the mechanism of enhancement of GABAA receptors to low concentrations of agonist by the nonimmobilizer F6.

The γ-subunit determines sensitivity to block

We found that the presence of the γ-subunit renders receptors incorporating α5 and β3 subunits insensitive to block by F6. That is, whereas heterodimeric α5β3 receptors activated by (near)-saturating concentrations of GABA were blocked by ~25% in the presence of 16 μM F6, no block of α5β3γ2 receptors was measurable. We reported previously that the γ-subunit exerts a similar effect when combined with α1β2 receptors.19 Therefore, this finding supports an emerging general principle that the γ-subunit plays an important modulatory role for the interaction of GABAARs with anesthetics and anesthetic-like compounds.19,22–24

F6 enhances responses to GABA

Similar to conventional inhaled anesthetics, F6 enhanced both α5β3 and α5β3γ2L receptors activated by low concentrations of GABA. This effect of F6 was seen at concentrations of F6 as low as 4 μM, or one-quarter of MACpred. Like conventional anesthetics, which cause amnesia at concentrations that are substantially lower than those required to prevent movement, low concentrations of F6 also impair the formation of long-term memories.4

Previously, enhancement was not observed for α1β2γ2S receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes.25 We replicated this finding for α1β2γ2L receptors, demonstrating that the lack of effect of F6 on α1β2γ2 receptors cannot be attributed to the expression system (mammalian human embryonic kidney 293 cells vs. frog oocytes), other technical factors (e.g., difficulties in preparing aqueous solutions of F626 or slow solution exchange around oocytes), or the specific splice variant of the γ-subunit that was used (γ2S vs. γ2L). Rather, this finding demonstrates that positive modulation by F6 depends on the specific α and/or β subunits incorporated into the GABAAR.

Common molecular sites for non-immobilizers and anesthetics?

Originally, a region of 45 amino acids within the TM2 and TM3 domains was identified as being critical for enhancement by enflurane and ethanol of responses to an EC10 concentration of GABA.5 Subsequently, single amino acid mutations in TM2 (N265M) and TM3 (M286W) of the β3 subunit were shown to result in a partial loss of sensitivity of expressed α2β3γ2 receptors to enhancement by etomidate and enflurane.8 The critical residues were proposed to line an intra-subunit cavity that can accommodate either an anesthetic molecule or an amino acid side chain.27 More recent results combining photoaffinity labeling with crystallography and structural modeling indicate that the N265 residue lies at the interface between adjacent α and β subunits.28,29 In either case, our present finding that the β3(N265M) mutation also renders α5β3γ2L receptors insensitive to enhancement by F6 demonstrates that this structural requirement for the enhancement of α5β3-subunit containing GABAARs applies to the nonimmobilizer F6 as well.

Since we did not test other subunit combinations, such as α5 combined with the β2 rather than β3 subunit, or α1 combined with β3 rather than β2, we cannot know with certainty which specific subunit or combination is critical to F6 sensitivity. Both β2- and β3-containing receptors are sensitive to etomidate, and both incorporate an asparagine residue at the 265 position, so both may also be sensitive to F6 when combined with the α5 subunit. Indeed, specific residues in α subunits, such as α1-S270, are key determinants of sensitivity to isoflurane and other inhaled drugs.27,30 If the identity of the α subunit is the critical factor for F6 sensitivity, the key differences must lie outside of the M2 membrane-spanning helix where the S270 residue is located, since the amino acid sequences of α1 and α5 subunits are identical in this region. Therefore, other domains of the α subunits or β subunits, or combinations thereof, must be the determining factors for F6 sensitivity.

Kinetic mechanisms of potentiation

Based on the currently available kinetic models of GABAAR function, the spectrum of macroscopic effects that we observed, enhancement of subsaturating responses with no effect on deactivation time course, limits the kinetic transitions upon which F6 could be acting to produce these effects.

Two agonist-binding sites are present at the 2α-β subunit interfaces,31 and both must be occupied for receptors to reach high levels of activation.32 Drugs that further stabilize the long-lived open state not only enhance responses to low concentrations of GABA, but also lead to a slowing of receptor deactivation after agonist removal.2 Therefore, this common mode of anesthetic action appears not to apply directly to F6. However, F6 could be acting through a slightly different but related mechanism, by stabilizing the short-lived open state produced by a receptor that is bound to a single molecule of GABA. Such an effect would enhance low-concentration responses without prolonging deactivation to the same extent as stabilization of the long-lived open state. Another possibility is that F6 might accelerate an agonist-binding step rather than directly altering channel gating. However, our finding that the N265M mutation in the TM region (near the channel gate but distant from the extracellular GABA binding site) influences F6 sensitivity, together with other studies showing that drugs that are thought to bind in this region increase the efficacy of partial agonists,33,34 suggest that anesthetics, and by analogy nonimmobilizers, alter gating transitions rather than agonist binding. Detailed studies of single-channel characteristics will be necessary to test these possibilities, and to better define the similarities and differences in molecular actions of conventional anesthetics versus F6.

Physiological implications

Pharmacological and physiological evidence indicates that the α5β3γ2L subunit combination is the most prevalent hippocampal form of receptors incorporating the α5 subunit.35–37 These subunits are highly colocalized in the dendritic layers (stratum radiatum and stratum oriens) of the CA1 and CA3 fields of the hippocampus.38,39 Compared with α1 subunits, α5 subunit-containing receptors display high GABA affinity and reduced desensitization.40,41 These properties enable them to mediate tonic inhibition as well as slow phasic inhibition in the dendrites,42 a spillover-mediated response that is produced by a subsaturating concentration of transmitter.43,44 Thus, F6 modulation of either tonic or slow dendritic inhibition may underlie its ability to impair hippocampus-dependent memory. In this regard, F6 might further share cellular- and network-level mechanisms of action with IV and inhaled general anesthetics, which are also proposed to impair memory via modulation of receptors that incorporate α514,41 and β311 subunits.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work supported by the National Institutes of Health [Grants GM55719, GM47818] and the UW Department of Anesthesiology.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Portions of this study were presented at the 2005 Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience (Washington, DC) and the 2006 Annual Meeting of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (Chicago, IL)

DISCLOSURES:

Name: Paul M. Burkat, MD, PhD

Contribution: This author helped conduct the study, analyze the data, and write the manuscript

Attestation: Paul M. Burkat has seen the original study data, reviewed the analysis of the data, and approved the final manuscript

Name: Chong Lor, BS

Contribution: This author helped conduct the study, analyze the data, and write the manuscript

Attestation: Chong Lor has seen the original study data, reviewed the analysis of the data, and approved the final manuscript

Name: Misha Perouansky, MD

Contribution: This author helped design the study and write the manuscript

Attestation: Misha Perouansky has seen the original study data, reviewed the analysis of the data, approved the final manuscript, and is the author responsible for archiving the study files

Name: Robert A. Pearce, MD, PhD

Contribution: This author helped design the study and write the manuscript

Attestation: Robert A. Pearce has seen the original study data, reviewed the analysis of the data, approved the final manuscript, and is the author responsible for archiving the study files

This manuscript was handled by:Markus W. Hollmann, MD, PhD, DEAA

Contributor Information

Paul M. Burkat, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Wisconsin SMPH, Madison, Wisconsin.

Chong Lor, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Wisconsin SMPH, Madison, Wisconsin.

Misha Perouansky, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Wisconsin SMPH, Madison, Wisconsin.

Robert A. Pearce, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Wisconsin SMPH, Madison, Wisconsin.

References

- 1.Rudolph U, Antkowiak B. Molecular and neuronal substrates for general anaesthetics. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:709–20. doi: 10.1038/nrn1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franks NP. General anaesthesia: from molecular targets to neuronal pathways of sleep and arousal. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:370–86. doi: 10.1038/nrn2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koblin DD, Chortkoff BS, Laster MJ, Eger EI, 2nd, Halsey MJ, Ionescu P. Polyhalogenated and perfluorinated compounds that disobey the Meyer-Overton hypothesis. Anesth Analg. 1994;79:1043–8. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199412000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dutton RC, Maurer AJ, Sonner JM, Fanselow MS, Laster MJ, Eger EI., 2nd Short-term memory resists the depressant effect of the nonimmobilizer 1-2-dichlorohexafluorocyclobutane (2N) more than long-term memory. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:631–9. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200203000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mihic SJ, Ye Q, Wick MJ, Koltchine VV, Krasowski MD, Finn SE, Mascia MP, Valenzuela CF, Hanson KK, Greenblatt EP, Harris RA, Harrison NL. Sites of alcohol and volatile anaesthetic action on GABA(A) and glycine receptors. Nature. 1997;389:385–9. doi: 10.1038/38738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borghese CM, Elsen FP, Werner DF, Topf N, Baron NV, Henderson LA, Boehm Ii SL, Saad A, Dai S, Pearce RA, Harris RA, Homanics GE, Harrison NL. Characterization of an isoflurane insensitive mutant GABAa receptor a1 subunit with near normal affinity for GABA in heterologous systems and knock-in-mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:208–18. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.104406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Werner DF, Blednov YA, Ariwodola OJ, Silberman Y, Logan E, Berry RB, Borghese CM, Matthews DB, Weiner JL, Harrison NL, Harris RA, Homanics GE. Knockin mice with ethanol-insensitive alpha1-containing gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors display selective alterations in behavioral responses to ethanol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:219–27. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.106161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siegwart R, Jurd R, Rudolph U. Molecular determinants for the action of general anesthetics at recombinant alpha(2)beta(3)gamma(2)gamma-aminobutyric acid(A) receptors. J Neurochem. 2002;80:140–8. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drexler B, Jurd R, Rudolph U, Antkowiak B. Dual actions of enflurane on postsynaptic currents abolished by the gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor beta3(N265M) point mutation. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:297–304. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200608000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sperk G, Schwarzer C, Tsunashima K, Fuchs K, Sieghart W. GABA(A) receptor subunits in the rat hippocampus I: immunocytochemical distribution of 13 subunits. Neuroscience. 1997;80:987–1000. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00146-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rau V, Oh I, Liao M, Bodarky C, Fanselow MS, Homanics GE, Sonner JM, Eger EI., 2nd Gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor beta3 subunit forebrain-specific knockout mice are resistant to the amnestic effect of isoflurane. Anesth Analg. 2011;113:500–4. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182273aff. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collinson N, Kuenzi FM, Jarolimek W, Maubach KA, Cothliff R, Sur C, Smith A, Otu FM, Howell O, Atack JR, McKernan RM, Seabrook GR, Dawson GR, Whiting PJ, Rosahl TW. Enhanced learning and memory and altered GABAergic synaptic transmission in mice lacking the alpha 5 subunit of the GABAA receptor. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5572–80. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05572.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crestani F, Keist R, Fritschy JM, Benke D, Vogt K, Prut L, Bluthmann H, Mohler H, Rudolph U. Trace fear conditioning involves hippocampal alpha5 GABA(A) receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8980–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142288699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng VY, Martin LJ, Elliott EM, Kim JH, Mount HT, Taverna FA, Roder JC, Macdonald JF, Bhambri A, Collinson N, Wafford KA, Orser BA. Alpha5GABAA receptors mediate the amnestic but not sedative-hypnotic effects of the general anesthetic etomidate. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3713–20. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5024-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saab BJ, Maclean AJ, Kanisek M, Zurek AA, Martin LJ, Roder JC, Orser BA. Short-term memory impairment after isoflurane in mice is prevented by the alpha5 gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor inverse agonist L-655,708. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:1061–71. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181f56228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin LJ, Zurek AA, MacDonald JF, Roder JC, Jackson MF, Orser BA. Alpha5GABAA receptor activity sets the threshold for long-term potentiation and constrains hippocampus-dependent memory. J Neurosci. 2010;30:5269–82. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4209-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chesney MA, Perouansky M, Pearce RA. Differential uptake of volatile agents into brain tissue in vitro. Measurement and application of a diffusion model to determine concentration profiles in brain slices. Anesthesiology. 2003;99:122–30. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200307000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li X, Czajkowski C, Pearce RA. Rapid and direct modulation of GABAA receptors by halothane. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:1366–75. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200005000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zarnowska ED, Pearce RA, Saad AA, Perouansky M. The gamma-subunit governs the susceptibility of recombinant gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors to block by the nonimmobilizer 1,2-dichlorohexafluorocyclobutane (F6, 2N) Anesth Analg. 2005;101:401–16. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000155264.67729.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mody I, Pearce RA. Diversity of inhibitory neurotransmission through GABA(A) receptors. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:569–75. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jurd R, Arras M, Lambert S, Drexler B, Siegwart R, Crestani F, Zaugg M, Vogt KE, Ledermann B, Antkowiak B, Rudolph U. General anesthetic actions in vivo strongly attenuated by a point mutation in the GABA(A) receptor beta3 subunit. FASEB J. 2003;17:250–2. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0611fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamashita M, Ikemoto Y, Nielsen M, Yano T. Effects of isoflurane and hexafluorodiethyl ether on human recombinant GABA(A) receptors expressed in Sf9 cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;378:223–31. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00468-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheller M, Forman SA. The gamma subunit determines whether anesthetic-induced leftward shift is altered by a mutation at alpha1S270 in alpha1beta2gamma2L GABA(A) receptors. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:123–31. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200107000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benkwitz C, Banks MI, Pearce RA. Influence of GABAA receptor gamma2 splice variants on receptor kinetics and isoflurane modulation. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:924–36. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200410000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mihic SJ, McQuilkin SJ, Eger EI, 2nd, Ionescu P, Harris RA. Potentiation of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor-mediated chloride currents by novel halogenated compounds correlates with their abilities to induce general anesthesia. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;46:851–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borghese CM, Harris RA. Anesthetic-induced immobility: neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are no longer in the picture. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:509–11. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200209000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koltchine VV, Finn SE, Jenkins A, Nikolaeva N, Lin A, Harrison NL. Agonist gating and isoflurane potentiation in the human gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor determined by the volume of a second transmembrane domain residue. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;56:1087–93. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.5.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li GD, Chiara DC, Sawyer GW, Husain SS, Olsen RW, Cohen JB. Identification of a GABAA receptor anesthetic binding site at subunit interfaces by photolabeling with an etomidate analog. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11599–605. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3467-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chiara DC, Dostalova Z, Jayakar SS, Zhou X, Miller KW, Cohen JB. Mapping general anesthetic binding site(s) in human alpha1beta3 gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors with [(3)H]TDBzl-etomidate, a photoreactive etomidate analogue. Biochemistry. 2012;51:836–47. doi: 10.1021/bi201772m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jenkins A, Greenblatt EP, Faulkner HJ, Bertaccini E, Light A, Lin A, Andreasen A, Viner A, Trudell JR, Harrison NL. Evidence for a common binding cavity for three general anesthetics within the GABAA receptor. J Neurosci. 2001;21Rc13:1–4. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-j0002.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boileau AJ, Evers AR, Davis AF, Czajkowski C. Mapping the agonist binding site of the GABAA receptor: evidence for a beta-strand. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4847–54. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-12-04847.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones MV, Sahara Y, Dzubay JA, Westbrook GL. Defining affinity with the GABA A receptor. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8590–604. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-08590.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Topf N, Jenkins A, Baron N, Harrison NL. Effects of isoflurane on gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors activated by full and partial agonists. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:306–11. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200302000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Downie DL, Hall AC, Lieb WR, Franks NP. Effects of inhalational general anaesthetics on native glycine receptors in rat medullary neurones and recombinant glycine receptors in Xenopus oocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;118:493–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15430.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luddens H, Seeburg PH, Korpi ER. Impact of beta and gamma variants on ligand-binding properties of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45:810–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sur C, Quirk K, Dewar D, Atack J, McKernan R. Rat and human hippocampal alpha5 subunit-containing gamma-aminobutyric AcidA receptors have alpha5 beta3 gamma2 pharmacological characteristics. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;54:928–33. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.5.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tietz EI, Kapur J, Macdonald RL. Functional GABAA receptor heterogeneity of acutely dissociated hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:1575–86. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.4.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sur C, Fresu L, Howell O, McKernan RM, Atack JR. Autoradiographic localization of alpha5 subunit-containing GABAA receptors in rat brain. Brain research. 1999;822:265–70. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pirker S, Schwarzer C, Wieselthaler A, Sieghart W, Sperk G. GABA(A) receptors: immunocytochemical distribution of 13 subunits in the adult rat brain. Neuroscience. 2000;101:815–50. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00442-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yeung JY, Canning KJ, Zhu G, Pennefather P, MacDonald JF, Orser BA. Tonically activated GABAA receptors in hippocampal neurons are high-affinity, low-conductance sensors for extracellular GABA. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:2–8. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Caraiscos VB, Elliott EM, You T, Cheng VY, Belelli D, Newell JG, Jackson MF, Lambert JJ, Rosahl TW, Wafford KA, MacDonald JF, Orser BA. Tonic inhibition in mouse hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons is mediated by {alpha}5 subunit-containing {gamma}-aminobutyric acid type A receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3662–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307231101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zarnowska ED, Keist R, Rudolph U, Pearce RA. GABAA receptor alpha5 subunits contribute to GABAA,slow synaptic inhibition in mouse hippocampus. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101:1179–91. doi: 10.1152/jn.91203.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Szabadics J, Tamas G, Soltesz I. Different transmitter transients underlie presynaptic cell type specificity of GABAA,slow and GABAA,fast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:14831–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707204104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Capogna M, Pearce RA. GABA A, slow: causes and consequences. Trends Neurosci. 2011;34:101–12. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]