Introduction

Variably protease-sensitive prionopathy (VPSPr) is a recently described novel prion disease biochemically characterized by abnormal prion protein (PrP) which has various degrees of sensitivity to proteases and generates a distinct profile on Western blots 1. VPSPr is the second most common sporadic prion protein disease after CJD 2. All reported cases to date have exhibited cognitive, behavioral, and psychiatric deficits with an age at onset range of 48-81 years and disease duration range of 7-72 months 1-4. Initial clinical diagnoses included normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), or frontotemporal dementia (FTD) 1,5, but Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) often was considered clinically after rapid decline became apparent 1.

All VPSPr cases evaluated have lacked mutations in the prion protein gene (PRNP) 1,2,5. Initial reports indicated all cases were homozygous for valine at codon 129 (VV) in PRNP 1. However, more recent reports have found VPSPr in all three codon 129 genotypes 2,5-7.

Here we report a case of VPSPr in which there were no known clinical manifestations of prion disease during life and yet pathognomonic findings were revealed at autopsy.

Methods

The individual described herein was enrolled in an ancillary study of cognitively normal individuals at the Knight Alzheimer's Disease Research Center at Washington University, St Louis, MO. She had 2 in-person assessments (1996 and 1999), although limited objective testing (Mini-Mental Status Exam (MMSE) 8) was obtained only at initial assessment. At death, her family was administered a postmortem dementia interview to ascertain any cognitive or neurological changes that may have occurred since her last in-person assessment 9. Pre-terminal hospitalization records were also reviewed. Genomic DNA had been extracted from blood during life for APOE genotyping by Knight Alzheimer's Disease Research Center Genetics Core 10.

After death, the brain was examined macroscopically. Paraffin sections from formalin-fixed blocks taken from 12 areas were obtained. These were processed using standard neuropathologic methods including hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and a modified Bielschowsky silver impregnation. Spongiform changes were noted and prompted further detailed evaluation in conjunction with the National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center (NPDPSC), Case Western University, Cleveland, OH, USA. Monoclonal antibodies used for immunohistochemistry were as follows: phosphorylated tau (PHF-1, a gift of Dr. P. Davies, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, NY, USA), beta-amyloid (10D5, Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN, USA), alpha-synuclein (LB509, Zymed Laboratories, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA), and PrP (3F4, EMD Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA )10.

DNA was extracted from frozen brain tissue for PRNP sequence analysis by the NPDPSC. The PRNP coding region was sequenced to determine the codon 129 genotype and the absence of pathogenic mutations 2. Frozen brain tissue was obtained and sent to the NPDPSC for prion protein characterization by proteinase K (PK) digestion and Western blot analysis 2,10. The brain tissue from the frontal cortex was used for Western blot analysis. Other brain regions were examined including occipital cortex, cerebellum, temporal cortex, striatum, midbrain, thalamus, and substantia nigra, in which much less PK-resistant protein was detected compared to the frontal cortex.

Results

Clinical Assessment

This individual was determined to be cognitively intact during her initial visit at age 87 with a MMSE 29 (only error was that she missed the date by 4 days) 8. Furthermore, she was determined to be cognitively intact at her death at age 93 with a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) score of 0, 11 as assessed by the retrospective collateral dementia interview (RCDI) 9. The RCDI is a structured telephone interview conducted by a clinician experienced in dementia evaluation with a knowledgeable collateral source. In particular, questions about memory and orientation are asked to elicit the onset, course, and nature of any problems (i.e., recent memory, orientation, and activities of daily living). Because the participant was asymptomatic, no additional clinical studies such as EEG, CSF (14-3-3) or imaging were obtained to evaluate the possibility of prion disease. Specifically, no neurologic abnormalities associated with prion disease were reported 2.

Chart review revealed no known risk factors for prion exposure. There was no family history of dementia. The RCDI was conducted with both her surviving spouse and their daughter, and neither had concerns about her memory and thinking abilities. She was oriented to her home and hometown. She continued to manage the household finances and paid the bills. She maintained her appointments but was less engaged in activities at her retirement home due to physical frailty. She continued to cook and work crossword puzzles. She maintained her activities of daily living and was only occasionally incontinent due to diuretics and physical limitations. She may have been depressed according to family. There was no history of seizures, strokes, unusual movements, tremors, visuospatial deficits, hallucinations, aphasia. This individual transitioned from assisted living to hospice care one month prior to expiration due to end-stage congestive heart failure. Her cause of death was due to inanition and congestive heart failure.

Genetic Findings

Genetic analysis of this individual was performed by the NPDPSC and confirmed both the absence of a mutation in the coding region of PRNP and the codon 129 genotype as being homozygous for methionine (MM). Her APOE genotype was ε3:ε3.

Neuropathology

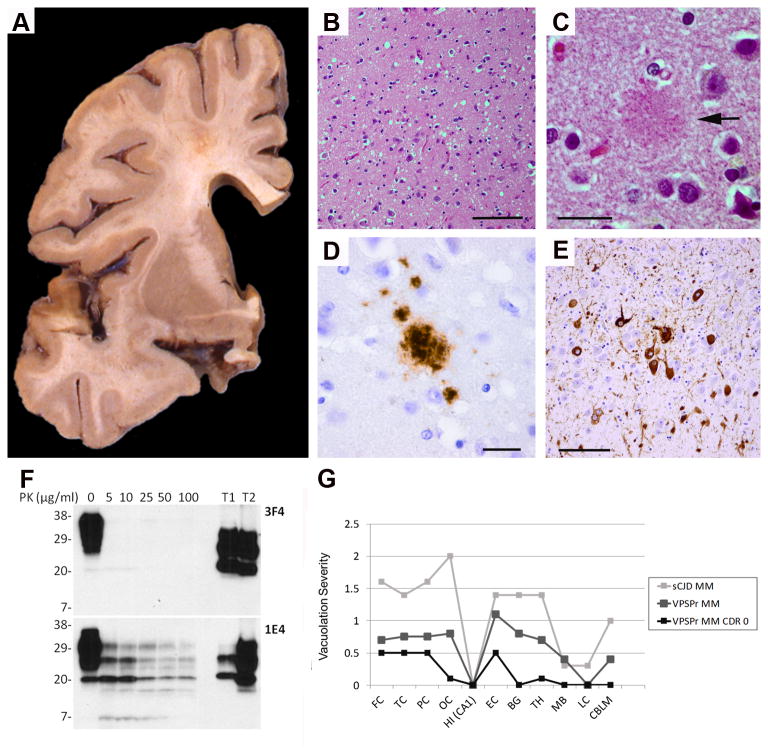

The fresh, unfixed brain weighed 1,180 g. There was mild atrophy of the frontal lobes and mild to moderate dilatation of the lateral ventricles. The amygdala and hippocampus were small in size. The basal ganglia and cerebellum were unremarkable (Figure A). Microscopic examination revealed pathognomonic changes for prion disease: neuronal loss and astrocytosis with spongiform changes in the deeper cortical layers of the frontal, parietal, and temporal neocortices were noted – in areas where initial pathological changes may precede the detection of PrP deposition by immunohistochemistry in CJD 12-14 (Figure B-E, Table). Furthermore, the current case exhibited a distinct and decreased vacuolation (“spongiform change”) profile as compared to sporadic CJD MM and previously described VPSPr MM cases (Figure G) 2. The cerebellum was unremarkable with a well-preserved complement of Purkinje and granule cells and neurons in the dentate nucleus. Weak PrP immunostaining revealed PrP deposits in the neocortex and none in the cerebellum (Figure D, Table). Mild Alzheimer's disease (AD) pathology was noted in the parahippocampal gyrus (Figure E, Table). Western blot analysis of frozen brain tissue from the frontal lobe of this case demonstrated the presence of a five band ladder-like electrophoretic profile of PrP that is fairly resistant to proteinase K (PK) digestion as expected in VPSPr-129MM, and that is distinct from sporadic CJD 2 (Figure F). As no beta-amyloid plaques were present, the neuropathologic diagnosis of AD was excluded 15. However, some neurofibrillary tangles (Braak neurofibrillary tangle stage III) were present in the medial temporal lobe. In conclusion, sufficient neuropathologic and biochemical evidence were present to support the diagnoses of VPSPr.

Figure.

A: There is mild dilatation of the lateral ventricle and some increase in space in the Sylvian fissure. The basal ganglia are unremarkable. B: There is mild and widespread moderate spongiform degeneration with vacuoles of intermediate size throughout the cortical ribbon of the frontal lobe. C: A rounded eosinophilic structure (arrow) indicates a possible prion plaque in the temporal cortex. D: Granular PrP plaques-like deposits in the temporal lobe. E: Neurofibrillary tangles in the parahippocampal gyrus. B and C, hematoxylin and eosin; D, PrP (3F4) immunohistochemistry; E, phosphorylated tau (PHF1) immunohistochemistry. Scale bars: B and E, 100μm; C and D, 20μm. F: Detection of prion protein by Western blotting. Brain homogenates from the frontal cortex of this case were subjected to treatment with different amounts of proteinase K (PK) prior to Western blotting with 3F42 or 1E4 21. T1 and T2: Disease causing PrP isoform (PrPSc) type 1 and type 2 from sporadic CJD positive controls. 3 μl of brain homogenate (∼120 μg protein) was loaded per lane. Numbers on the left sides of the blots refer to the molecular weights of standards used. G: Vacuolation profiles. The current VPSPr MM CDR 0 case exhibits a distinct and decreased vacuolation profile as compared to sporadic CJD MM and previously described VPSPr MM cases 2. Semi-quantitative assessment of vacuolation scored on the y-axis on a 0 to 4 scale (0 = not detectable; 1 = mild; 2 = moderate; 3 = severe; 4 = confluent) 1. X-axis abbreviations: FC – Frontal cortex; TC – Temporal cortex; PC – Parietal cortex; OC – Occipital cortex; HIP (CA1)– Hippocampus CA1 subfield; EC – Entorhinal cortex; BG – Basal ganglia; TH – Thalamus; MB – Midbrain; LC – Locus coeruleus; CBLM – Cerebellum.

Table.

Neuron loss, gliosis, and prion protein (PrP) deposits

| Area | Neuron loss/gliosis | Vacuolation | PrP | NFT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FC | + | ++ | + | 0 |

| TC | + | ++ | + | 0 |

| PC | + | ++ | + | 0 |

| OC | +/- | +/- | 0 | 0 |

| HIP | +/- | 0 | 0 | + |

| EC | + | ++ | + | ++ |

| BG | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TH | + | + | + | 0 |

| SN | +/- | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| LC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MED | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CBLM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Abbreviations: FC – Frontal cortex; TC – Temporal cortex; PC – Parietal cortex; OC – Occipital cortex; HIP – Hippocampus; EC – Entorhinal cortex; BG – Basal ganglia; TH – Thalamus; SN – Substantia nigra; LC – Locus coeruleus; MED – Medulla; CBLM – Cerebellum.

Discussion

We describe herein the first report of histopathologically diagnosed VPSPr in a 93-year-old individual lacking clinically recognized cognitive, behavioral, or neurologic deficits at the time of death, as based on the RCDI and pre-terminal hospitalization records. Although it is possible that she may have had undetected neurological signs and symptoms, they were not appreciated by her family or her medical team. While other VPSPr cases of long duration have been reported, they were all symptomatic with findings consistent with Parkinson's disease or an underlying psychiatric illness, or else they exhibited myoclonus, ataxia, or aphasia 1,2,4,5,16-18. Our asymptomatic case had no prion disease exposures and had no family history of dementing illnesses.

One possibility is that the autopsy-confirmed VPSPr in our cognitively normal case may have led to symptomatic disease had she continued to live. Pathologically, VPSPr MM typically has medium-sized vacuoles and microplaques in the cerebellum 4. In our case, the characteristic vacuolation pattern found in VPSPr was notably reduced, which suggests overall low pathological burden. PrP grains and plaques were found in the temporal lobe while the cerebellum was normal. There is a VPSPr MV case report with normal cerebellum but that case was also symptomatic with cognitive and visuospatial deficits in the context of coexisting tau, beta-amyloid, and alpha-synuclein lesions 19. It is possible that longer duration was needed in this case to increase vacuole and PrP burden to a threshold at which point symptoms would manifest. In transgenic mouse models an age-dependent accumulation of prions and their infectivity has been shown to be inversely proportional to incubation time 20. Presymptomatic Tg2866 mice sacrificed at 56 days conferred no infectivity to Tg196 mice, but presymptomatic mice sacrificed at 112 days were able to induce disease in the Tg196 mice and after a shorter incubation time than if sacrificed at 84 days 20.

The VPSPr MM subtype also appears to be less prevalent and less severe in disease presentation (less severe histopathology and less prominent PrP immunostaining) when considering that 25 of 28 VPSPr cases in one series had at least one valine (V) allele 2,5. VPSPr MM is characteristically more resistant to PK such that a ladder of fragments persists even after relatively high concentration PK exposure as is seen in our case 2,4-6. Although the brain tissue in this case was not evaluated for infectivity, it is theoretically possible based on animal data 20 that even minimal pathology could be transmissible. To our knowledge, this is the first case report of VPSPr in a cognitively and neurologically intact person and adds to the growing spectrum of prion disease phenotypes.

Acknowledgments

Support: P50 AG005681, P01 AG003991 (NG, NJC, JCM); K12 HD001459 (NG); The Patrick Yobs Gerstmann-Straussler-Sheinker Grant (GP); P01 AG014359, CDC UR8/CCU515004 and the Charles S. Britton Fund (PG)

Support for this work was provided by the NIA and NICHD of the National Institutes of Health. Detailed support listed under Acknowledgments.

Author Disclosure Information

N. Ghoshal

Role: design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript

Dr. Ghoshal had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Neither Dr. Ghoshal nor her family owns stock or has equity interest (outside of mutual funds or other externally directed accounts) in any pharmaceutical or biotechnology company. Dr. Ghoshal has participated or is currently participating in clinical trials of antidementia drugs sponsored by: Elan/Janssen, Eli Lilly and Company, Wyeth, Pfizer, Novartis, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, Other financial or material support. None.

A. Perry –Per CTA

Role: Collection and interpretation of the data; and approval of the manuscript

D. McKeel – Per CTA

Role: Collection and interpretation of the data; and approval of the manuscript

R.E. Schmidt – Per CTA

Role: Collection and interpretation of the data; and approval of the manuscript

D. Carter – Per CTA

Role: Collection, management of the data; and approval of the manuscript

J. Norton – Per CTA

Role: Collection, management of the data; and approval of the manuscript

W-Q. Zou – Per CTA

Role: design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and approval of the manuscript

X. Xiao – Per CTA

Role: design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and approval of the manuscript

G. Puoti, None

Role: design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and approval of the manuscript

S. Notari, Per CTA

Role: design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and approval of the manuscript

P. Gambetti.

Role: design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript

Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Grants/Research Support; Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Consultant; Member of the TSE Advisory Board, Board Member/Officer;

J.C. Morris:

Role: design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript

Neither Dr. Morris nor his family owns stock or has equity interest (outside of mutual funds or other externally directed accounts) in any pharmaceutical or biotechnology company. Dr. Morris has participated or is currently participating in clinical trials of antidementia drugs sponsored by: Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Program, Pfizer, and Eli Lilly/Avid Radiopharmaceuticals. Dr. Morris as served as a consultant or has received speaking honoraria from: Lilly USA. Other financial or material support. None.

N.J. Cairns, None

Role: design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Gambetti P, Dong Z, Yuan J, et al. A novel human disease with abnormal prion protein sensitive to protease. Ann Neurol. 2008 Jun;63(6):697–708. doi: 10.1002/ana.21420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zou WQ, Puoti G, Xiao X, et al. Variably protease-sensitive prionopathy: a new sporadic disease of the prion protein. Ann Neurol. 2010 Aug;68(2):162–172. doi: 10.1002/ana.22094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodriguez-Martinez AB, de Munain AL, Ferrer I, et al. Coexistence of protease sensitive and resistant prion protein in 129VV homozygous sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: a case report. Journal of medical case reports. 2012;6(1):348. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-6-348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Head MW. Human prion diseases: Molecular, cellular and population biology. Neuropathology. 2013 Jan 20; doi: 10.1111/neup.12016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gambetti P, Puoti G, Zou WQ. Variably protease-sensitive prionopathy: a novel disease of the prion protein. J Mol Neurosci Nov. 2011;45(3):422–424. doi: 10.1007/s12031-011-9543-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gambetti P, Puoti G, Kong Q, et al. Novel Human Prion Disease Affecting 3 Prion Codon 129 Genotypes: The Sporadic Form of Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker Disease?. Paper presented at: 85th Annual Meeting of American Association of Neuropathologists, Inc.; May 2009, 2009; San Antonio, Texas. June 11-14, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodriguez-Martinez AB, Garrido JM, Zarranz JJ, et al. A novel form of human disease with a protease-sensitive prion protein and heterozygosity methionine/valine at codon 129: Case report. BMC neurology. 2010;10:99. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-10-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis PB, White H, Price JL, et al. Retrospective postmortem dementia assessment. Validation of a new clinical interview to assist neuropathologic study. Arch Neurol Jun. 1991;48(6):613–617. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1991.00530180069019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghoshal N, Cali I, Perrin RJ, et al. Codistribution of amyloid beta plaques and spongiform degeneration in familial Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease with the E200K-129M haplotype. Arch Neurol Oct. 2009;66(10):1240–1246. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993 Nov;43(11):2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armstrong RA, Cairns NJ. Spatial patterns of the pathological changes in the cerebellar cortex in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD) Folia Neuropathol. 2003;41(4):183–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Armstrong RA. Spatial correlations between the vacuolation, prion protein (PrPsc) deposits and the cerebral blood vessels in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Curr Neurovasc Res Nov. 2009;6(4):239–245. doi: 10.2174/156720209789630339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Armstrong RA, Lantos PL, Cairns NJ. Quantification of the pathological changes with laminar depth in the cortex in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Pathophysiology : the official journal of the International Society for Pathophysiology / ISP. 2001 Dec;8(2):99–104. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4680(01)00072-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol. 2012 Jan;123(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0910-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Head MW, Knight R, Zeidler M, et al. A case of protease sensitive prionopathy in a patient in the UK. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2009 Dec;35(6):628–632. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2009.01040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jansen C, Head MW, van Gool WA, et al. The first case of protease-sensitive prionopathy (PSPr) in The Netherlands: a patient with an unusual GSS-like clinical phenotype. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010 Sep;81(9):1052–1055. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.175646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sikorska B, Liberski PP. Human prion diseases: from kuru to variant creutzfeldt-jakob disease. Subcell Biochem. 2012;65:457–496. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-5416-4_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Head MW, Lowrie S, Chohan G, et al. Variably protease-sensitive prionopathy in a PRNP codon 129 heterozygous UK patient with co-existing tau, alpha synuclein and Abeta pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2010 Dec;120(6):821–823. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0766-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tremblay P, Ball HL, Kaneko K, et al. Mutant PrPSc conformers induced by a synthetic peptide and several prion strains. J Virol. 2004 Feb;78(4):2088–2099. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.4.2088-2099.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuan J, Dong Z, Guo JP, et al. Accessibility of a critical prion protein region involved in strain recognition and its implications for the early detection of prions. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008 Feb;65(4):631–643. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7478-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]