Abstract

Background

Cefadroxil, a cephalosporin antibiotic, is a substrate for several membrane transporters including peptide transporter 2 (PEPT2), organic anion transporters (OATs), multidrug resistance-associated proteins (MRPs), and organic anion transporting polypeptides (OATPs). These transporters are expressed at the blood–brain barrier (BBB), blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier (BCSFB), and/or brain cells. The effect of these transporters on cefadroxil distribution in brain is unknown, especially in the extracellular and intracellular fluids within brain.

Methods

Intracerebral microdialysis was used to measure unbound concentrations of cefadroxil in rat blood, striatum extracellular fluid (ECF) and lateral ventricle cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The distribution of cefadroxil in brain was compared in the absence and presence of probenecid, an inhibitor of OATs, MRPs and OATPs, where both drugs were administered intravenously. The effect of PEPT2 inhibition by intracerebroventricular (icv) infusion of Ala-Ala, a substrate of PEPT2, on cefadroxil levels in brain was also evaluated. In addition, using an in vitro brain slice method, the distribution of cefadroxil in brain intracellular fluid (ICF) was studied in the absence and presence of transport inhibitors (probenecid for OATs, MRPs and OATPs; Ala-Ala and glycylsarcosine for PEPT2).

Results

The ratio of unbound cefadroxil AUC in brain ECF to blood (Kp,uu,ECF) was ~2.5-fold greater during probenecid treatment. In contrast, the ratio of cefadroxil AUC in CSF to blood (Kp,uu,CSF) did not change significantly during probenecid infusion. Icv infusion of Ala-Ala did not change cefadroxil levels in brain ECF, CSF or blood. In the brain slice study, Ala-Ala and glycylsarcosine decreased the unbound volume of distribution of cefadroxil in brain (Vu,brain), indicating a reduction in cefadroxil accumulation in brain cells. In contrast, probenecid increased cefadroxil accumulation in brain cells, as indicated by a greater value for Vu,brain.

Conclusions

Transporters (OATs, MRPs, and perhaps OATPs) that can be inhibited by probenecid play an important role in mediating the brain-to-blood efflux of cefadroxil at the BBB. The uptake of cefadroxil in brain cells involves both the influx transporter PEPT2 and efflux transporters (probenecid-inhibitable). These findings demonstrate that drug-drug interactions via relevant transporters may affect the distribution of cephalosporins in both brain ECF and ICF.

Keywords: Blood–brain barrier, Blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier, Intracerebral microdialysis, Brain slice, Cefadroxil, Multidrug resistance-associated proteins, Organic anion transporters, Organic anion transporting polypeptides, Peptide transporter 2, Probenecid

Background

Cephalosporins, a class of beta-lactam antibiotics, have been widely used for the prophylaxis and treatment of a variety of infections [1]. In addition to their antibacterial activity, the therapeutic effects of different cephalosporins depend on their pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution, which are affected by multiple membrane transporters. Some cephalosporins are substrates of proton-coupled oligopeptide transporters (POTs) [2], organic anion transporters (OATs) [3], organic anion transporting polypeptides (OATPs) [4, 5], and multidrug resistance-associated proteins (MRPs) [6, 7]. These transporters are widely distributed in several tissues including the kidney, liver, intestine, and brain [8], influencing cephalosporin absorption, distribution, and elimination.

Among all tissues, drug delivery to brain is the most challenging because of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), situated at the cerebral endothelium, and blood-CSF barrier (BCSFB) at the choroid plexus epithelium [9]. In addition to tight junctions limiting paracellular diffusion [10, 11], the BBB and BCSFB express many transporters responsible for chemical exchange between brain and blood including efflux transporters important for protecting the brain from waste products and potential toxins [12]. Among the cephalosporin transporters, the MRPs and OATs at the BBB and BCSFB are believed to transport substrates from brain (and CSF) to blood as efflux transporters [13–15]. Peptide transporter 2 (PEPT2, a member of POTs) at the apical side (CSF facing) of the BCSFB is able to transport substrates from the CSF side towards blood [16]. The OATPs are expressed both at the BBB and BCSFB as bidirectional transporters [17, 18]. The above mentioned transporters are also expressed on the cell membrane of brain cells (neurons, astrocytes, and microglia) [13, 14, 18, 19], potentially affecting cephalosporin distribution after their entry into brain. Thus, membrane transporters may influence the brain distribution of cephalosporins and influence their effectiveness for treating central nervous system (CNS) infections.

Cefadroxil is a first-generation cephalosporin and used clinically mainly to treat urinary tract infections [1]. The current study employed cefadroxil as a model drug to examine the potential impact of transporters on the brain distribution of cephalosporins, as it has been reported to be a substrate of POTs, OATs, MRPs, and OATPs [5, 6, 20–22]. In small intestine, PEPT1, a member of POTs, mediates peptide/mimetic uptake at the apical side of enterocytes, leading to a high oral bioavailability [23, 24]. Thus, PEPT1 knockout led to a 23-fold reduction in peak plasma concentrations and a 14-fold decrease in systemic exposure of cefadroxil in mice [24]. Also, MRP3 and MRP4, at the basolateral side of enterocytes, may contribute to the further transport of cefadroxil from enterocyte to blood [22]. The kidney is the main elimination organ for cefadroxil and studies in PEPT2 null mice indicate that this is the principal transporter involved in cefadroxil reabsorption [20]. Moreover, the clearance of cefadroxil is significantly reduced by co-administration of probenecid [20, 25]. Probenecid is widely known as an inhibitor of OATs, which mediates renal secretion at the basolateral membrane of proximal tubule epithelia. However, probenecid can also inhibit the MRPs and OATPs that transport substrates from blood to urine via the kidney [26, 27].

Studies on the distribution of cefadroxil in brain have focused on the function of PEPT2 at the BCSFB and brain cells. PEPT2 in choroid plexus removes cefadroxil from CSF. As a result, the CSF-to-blood concentration ratio of cefadroxil in wild-type mice was markedly lower than that in PEPT2 knockout mice [20, 28]. In addition, cefadroxil inhibited the uptake of PEPT2 substrates in rodent neonatal astrocytes, demonstrating an uptake function of PEPT2 in brain cells [19, 29, 30]. However, there are no studies on the influence of transporters on the distribution of cefadroxil in brain extracellular fluid (ECF). A deeper understanding of the effect of transporters on CNS cephalosporin distribution is helpful for the more efficient use of cephalosporins for treating brain infections like meningitis.

The present study examined the impact of transporters on cefadroxil distribution in brain ECF and CSF using probenecid, an inhibitor of OATs, MRPs and OATPs, as well as Ala-Ala, a substrate of PEPT2. In vivo microdialysis was applied to measure cefadroxil concentrations in rat brain ECF, CSF and blood. In addition, an in vitro brain slice method was performed to study cefadroxil distribution within the rat brain parenchyma.

Methods

Chemicals

Cefadroxil, cefadroxil-D4 (deuterated), probenecid, Ala-Ala, glycylsarcosine (GlySar), and amoxicillin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), isoflurane from Baxter Medical AB (Kista, Sweden), and 100 IU/mL heparin from Leo Pharma AB (Malmö, Sweden). Acetonitrile and formic acid were obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). All other chemicals were of analytical grade or better. Ringer’s solution was used to perfuse the microdialysis probes and consisted of 145 mM NaCl, 0.6 mM KCl, 1.0 mM MgCl2, and 1.2 mM CaCl2 in 2 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. Artificial extracellular fluid (aECF), used to buffer the brain slices, was comprised of 10 mM glucose, 129 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 0.4 mM K2HPO4, 1.4 mM CaCl2, and 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.6, at room temperature. Normal saline was obtained from Braun Medical AB (Stockholm, Sweden) and the Milli-Q system (Millipore, Bedford, Massachusetts) was used to purify the water.

Animals

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (260–300 g) were obtained from Taconic (Lille Skensved, Denmark). Rats were acclimated for at least 7 days in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment with 12-hour light/dark cycles before study. The protocols in this study were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Uppsala University, Sweden (C351/11 and C328/10).

Microdialysis study of cefadroxil in the absence and presence of probenecid

Surgery was performed one day before microdialysis in order to implant vessel catheters and microdialysis probes as described previously [31] with modification. Briefly, under isoflurane anesthesia and with body temperature controlled at 38°C (CMA/150 temperature controller, CMA, Stockholm, Sweden), catheters were inserted into the left femoral vein for cefadroxil infusion, the left jugular vein for control (Day 1) or probenecid infusion (Day 2), and the left femoral artery for blood sampling. A CMA/20 probe with 10 mm polyarylethersulphone (PAES) membrane was inserted into the right jugular vein. The rat was then fixed on a stereotaxic frame equipped with an anesthesia mask. Two guide cannulas were implanted into the brain striatum (ST coordinates, +0.2 mm anteroposterior, −4.7 mm lateral, −3.8 mm dorsoventral with an angle of 15° at the coronal plane towards midline) and lateral ventricle (LV coordinates, −0.9 mm anteroposterior, +1.6 mm lateral, −2.9 mm dorsoventral), and fixed to the skull by a screw and dental cement. A CMA 12 probe with 3 mm PAES membrane was inserted into the striatal guide cannula for monitoring brain ECF and a CMA 12 probe with 1 mm PAES membrane was inserted into the ventricular guide cannula for CSF sampling. At the end of the surgery, the rat was placed in a CMA 120 system for freely moving animals in which it had free access to food and water, and allowed to recover for 24 hours before experimentation.

On Day 1, a 90-min stabilization period was performed in which Ringer’s solution, containing cefadroxil-D4, was perfused through the microdialysis probes by pump (CMA 400, Solna, Sweden) at a flow rate of 0.5 μL/min. During this period, and throughout the entire experiment (another 420 min), microdialysis samples (10 μL each) were collected every 20 min using a fraction collector (CMA 142, Solna, Sweden) and stored at 4°C until analysis. To quantify unbound drug concentrations in brain and blood, cefadroxil-D4 was used to calibrate the probes using retrodialysis [32]. Because cefadroxil levels in brain and blood were quite different, 1 μg/mL cefadroxil-D4 was used to perfuse the blood probe and 0.1 μg/mL for the brain probe. At 90 min, cefadroxil solution (6 mg/mL in normal saline) was administered intravenously (iv) as a bolus infusion of 0.3 mg/kg/min for 20 min followed by a constant-rate infusion of 0.15 mg/kg/min for 160 min (for a total of 180 min). In addition to the microdialysis samples, arterial blood samples (100 μL) were drawn predose and at 5, 18, 90, 150, 185, 190, 210, 240, 300, and 420 min after initiating the cefadroxil bolus infusion. Plasma was harvested from blood after centrifuging at 7200 g for 5 min and then frozen at −20°C until analysis. On Day 2, the cefadroxil experiment was repeated, however, 15 mg/mL probenecid in 5% NaHCO3 in saline (as opposed to 5% NaHCO3 in saline only on Day 1) was added as a 20 mg/kg bolus followed by 20 mg/kg/hr infusion for 420 min (i.e., cefadroxil in the presence of probenecid).

Microdialysis study of cefadroxil in the absence and presence of Ala-Ala

The surgery and microdialysis method for this study was similar to that described before for probenecid except, in this case, the dipeptide Ala-Ala was administered instead and by intracerebroventricular (icv) infusion. In order to perform the microdialysis sampling and icv infusion simultaneously, a microdialysis probe with an additional infusion cannula passing through the lumen of probe (IBR combination probe with 1 mm polyacrylanitrile membrane, BASi, West Lafayette, IN, USA) was implanted into the lateral ventricle (coordinates, −0.9 mm anteroposterior, −1.6 mm lateral, −2.9 mm dorsoventral). For these studies (i.e., cefadroxil in the absence and presence of Ala-Ala), the experiment was performed in one day. In brief, following the 90-min stabilization period, cefadroxil saline solution was infused iv at 0.3 mg/kg/min for 20 min followed by 0.15 mg/kg/min for 400 min (for a total of 420 min). An icv infusion of Ringer’s solution, 0.3 μL/min, was started 30 min prior to cefadroxil administration and maintained for another 240 min (control phase). At this time, an icv infusion of 0.32 mg/mL Ala-Ala in Ringer’s solution was started and then maintained for another 180 min.

In vitrobrain slice study

The brain slice protocol was based on a previously published method with minor modifications [33]. Briefly, fresh brains were collected in which six 300-μm coronal slices were prepared from each animal using a microtome (Leica VT1200, Leica Microsystems AB, Sweden). Resultant slices were transferred to an 80-mm diameter beaker with 15 mL aECF containing 0.8 μM cefadroxil with or without 5 mM GlySar, 5 mM Ala-Ala, or 1 mM probenecid. Covered by a lid comprised of a Teflon fluorinated ethylene-propylene film (DuPont, Katco Ltd, UK), the beaker was incubated in a shaker (MaxQ4450, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Nino Lab, Sweden) at 45 rpm, 37°C, for 2 hr. Throughout the incubation, there was a constant flow of oxygen into the shaking chamber to maintain slice viability. After incubation, 200 μL of blank rat brain homogenate without cefadroxil was added to 200 μL of buffer sample to keep the matrix consistent among all the samples for the following analysis. The brain slices were then weighed, after drying on filter paper, and homogenized individually in aECF (9:1 ratio, w/v) using an ultrasonic processor (VCX-130, Sonics, Chemical Instruments AB, Sweden). All samples were stored at −20°C until analysis.

In all experiments, coronal slices were prepared from the same anatomical plane corresponding to the striatal region (no midbrain structures) in order to avoid potential discrepancies in the assessment of the unbound volume of distribution of cefadroxil in brain (Vu,brain). In our studies, the Vu,brain values of cefadroxil were similar in each rat with little variability (mean coefficient of variation ≤5.4%). Potential regional differences in the Vu,brain of cefadroxil were not studied.

Chemical analysis

The analysis of cefadroxil (and cefadroxil D-4) was carried out using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Specifically, 5 μL microdialysis samples were injected into the LC-MS/MS after adding amoxicillin solution as an internal standard. For plasma and homogenate samples, the proteins were precipitated by adding acetonitrile at a ratio of 1:3. After centrifuging at 7200 g for 3 min, the supernatant was diluted with 0.1% formic acid before injecting into the LC-MS/MS. Standard curves and quality control samples were used to quantify and validate the concentrations of cefadroxil in all biological matrices from the study.

Chromatographic separation was achieved on a HyPurity C18 column (50 × 4.6 mm, particle size 3 μm) protected by a HyPurity C18 guard-column (10 × 4.0 mm, particle size 3 μm; Thermo Hypersil-Keystone, PA, USA). A gradient elution involving mobile phase A (0.1% formic acid) and mobile phase B (0.1% formic acid in 1:1 acetonitrile:water) was delivered by two Shimadzu LC-10ADvp pumps (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) at 0.8 mL/min, which was split to 0.3 mL/min before entering the MS detector. A Quattro Ultima Pt mass spectrometer (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) was used for detection on positive electrospray ionization (ESI+) mode. The transition mode was m/z 363.9 → 207.9 for cefadroxil, m/z 368.0 → 212.0 for cefadroxil-D4, and m/z 366.0 → 348.9 for amoxicillin. All data were acquired and processed using Masslynx 4.1 (Waters, Milford, MA, USA).

Data analysis

The relative recovery of cefadroxil in each microdialysis probe was estimated from retrodialysis of the calibrator, cefadroxil-D4, and calculated as:

| 1 |

where Cin,CEF-D4 is the concentration of cefadroxil-D4 in perfusate and Cout,CEF-D4 is the concentration of cefadroxil-D4 in dialysate. The unbound concentrations of cefadroxil in blood (Cu,blood), brain ECF (Cu,ECF), and CSF (Cu,CSF) were calculated from their respective concentrations in dialysate (Cdialysate) as:

| 2 |

For the microdialysis study of cefadroxil (with and without probenecid), the trapezoidal method was used to calculate area under the curve for unbound cefadroxil (AUCu) in blood, ECF, and CSF from 0–420 min. AUCu values from 420 min to infinity were determined by extrapolation from the time of the last measured concentration Clast according to  , in which λz is the terminal rate constant obtained from the slope of the last 7 observations. The blood concentration of cefadroxil at steady-state (Cu,ss,blood) was calculated from the average of concentrations during the 120–180 min time period. The unbound partition coefficient of cefadroxil in brain ECF (Kp,uu,ECF) and CSF (Kp,uu,CSF) was obtained as follows:

, in which λz is the terminal rate constant obtained from the slope of the last 7 observations. The blood concentration of cefadroxil at steady-state (Cu,ss,blood) was calculated from the average of concentrations during the 120–180 min time period. The unbound partition coefficient of cefadroxil in brain ECF (Kp,uu,ECF) and CSF (Kp,uu,CSF) was obtained as follows:

| 3 |

| 4 |

Non-compartmental analyses were performed using the microdialysis samples from blood to obtain the pharmacokinetic parameters of unbound cefadroxil, in which area under the moment curve (AUMCu) was also obtained by trapezoidal method. The mean input time (MIT) was 66 min calculated from  , where R0 and Tin denote the infusion rate and infusion time of the two consecutive cefadroxil infusions. With the correction of MIT, the mean residence time with an iv bolus (MRTiv) was obtained:

, where R0 and Tin denote the infusion rate and infusion time of the two consecutive cefadroxil infusions. With the correction of MIT, the mean residence time with an iv bolus (MRTiv) was obtained:

| 5 |

The total clearance (CL), volume of distribution steady-state (Vss), and half-life (t1/2) were calculated based on the total cefadroxil dose (30 mg/kg, which includes both the bolus and constant-rate infusions), along with AUCu and AUMCu from times zero to infinity (inf):

| 6 |

| 7 |

| 8 |

For the microdialysis study of cefadroxil with and without Ala-Ala, Kp,uu was calculated from the unbound concentration of drug at steady-state (Cu,ss,ECF or Cu,ss,CSF) by:

| 9 |

where Cu,ss was calculated during the 120–200 min time period for the control phase (i.e., without Ala-Ala) and during the 320–420 min time period for the dipeptide phase (i.e., with Ala-Ala).

In analyzing brain slice data, the unbound volume of distribution in brain (Vu,brain, in mL/g brain) was calculated for cefadroxil as:

| 10 |

where Abrain is the total amount of cefadroxil in brain slice, Cbuffer is the concentration of cefadroxil in buffer at the end of incubation, and Vi is the volume of buffer film surrounding the brain slice because of incomplete adsorption by the filter paper; Vi was reported as 0.094 mL/g brain [34].

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. A two-tailed paired t-test was used to compare cefadroxil parameters between the control and inhibition phases. A value of p <0.05 was considered statistically significant. For the brain slice study, a one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test was performed to compare each treatment group to the control. GraphPad Prism v5.04 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Microdialysis study of cefadroxil in the absence and presence of probenecid

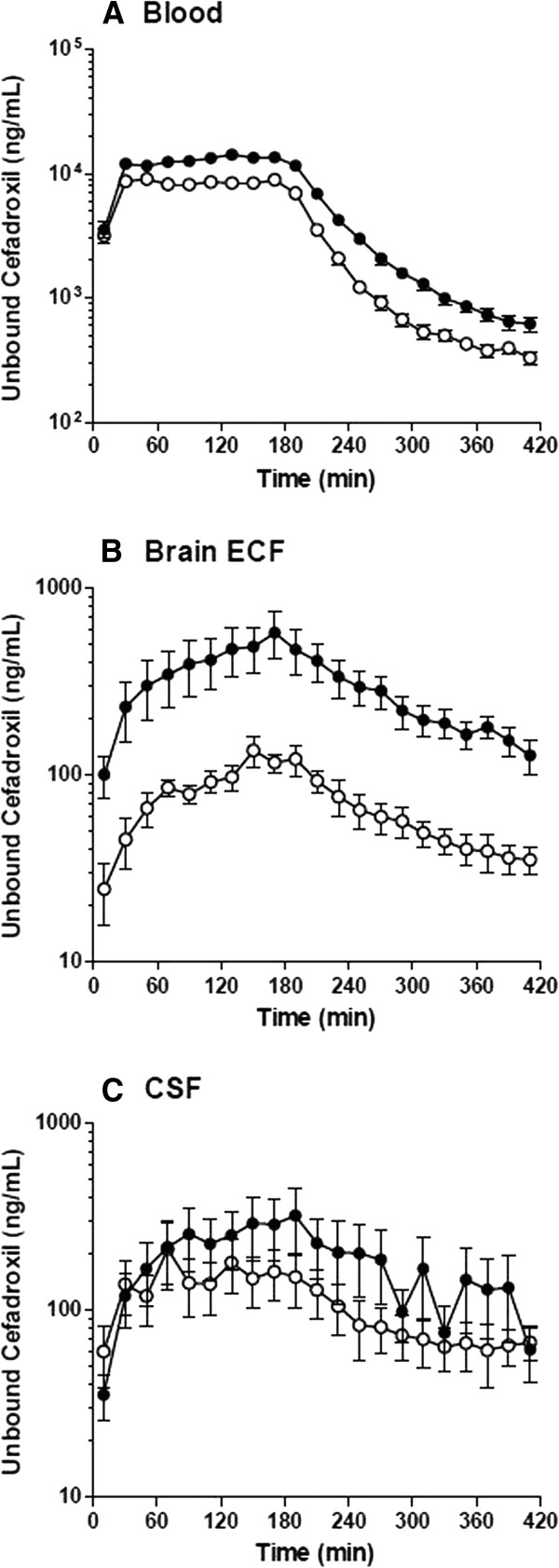

There were no significant differences in probe relative recoveries between the two days. The recoveries were 14 ± 1% for the 3-mm probe in brain ECF, 6.7 ± 1.1% for the 1-mm probe in lateral ventricle, and 71 ± 2% for the 10-mm probe in blood. As shown in Figure 1A, steady-state concentrations of cefadroxil in blood were quickly achieved after the bolus infusion of 0.3 mg/kg/min for 20 min followed by the constant-rate infusion of 0.15 mg/kg/min for 160 min. Compared to Day 1 (control phase), probenecid infusion increased Cu,ss,blood and AUCu of cefadroxil by ~60%. The elevated systemic exposure probably resulted from a decrease in cefadroxil clearance from 16.9 ± 1.0 to 10.7 ± 0.7 mL/min/kg (Table 1). However, the MRT and t1/2 did not differ significantly between days, reflecting a reduced volume of distribution (Vss) with probenecid, indicating probenecid may decrease the accumulation of cefadroxil in certain tissues. Plasma cefadroxil concentrations (data not shown) were comparable to the unbound blood concentrations from microdialysis, consistent with previous studies showing that the unbound fraction of cefadroxil in plasma (fu) is nearly 1.0 [35].

Figure 1.

The concentration-time profiles of unbound cefadroxil in rat blood (A), brain ECF (B), and CSF (C) in the absence and presence of probenecid. Open circles represent the results from Day 1 (no probenecid) and solid circles the results from Day 2 (with probenecid). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6).

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of unbound cefadroxil in rat blood and brain on Day 1 (Control, Ctrl) and Day 2 (with probenecid, Pro)

| Parameters | Unit | Day 1 (Ctrl) | Day 2 (Pro) | Pro/Ctrl |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | ||||

| AUCu (0–420) | μg*min/mL | 1747 ± 90 | 2801 ± 175*** | 1.60 |

| AUCu (0-inf) | μg*min/mL | 1802 ± 97 | 2873 ± 177*** | 1.59 |

| Cu,ss,blood | μg/mL | 8.5 ± 0.4 | 13.8 ± 0.9*** | 1.62 |

| MRTiv | min | 71 ± 4 | 77 ± 4 | 1.05 |

| t1/2 | min | 49 ± 2 | 53 ± 3 | 1.09 |

| CL | mL/min/kg | 16.9 ± 1.0 | 10.7 ± 0.7*** | 0.63 |

| Vss | L/kg | 1.19 ± 0.12 | 0.82 ± 0.10*** | 0.69 |

| Brain ECF | ||||

| AUCu (0–420) | μg*min/mL | 31 ± 5 | 122 ± 31* | 3.93 |

| AUCu (0-inf) | μg*min/mL | 40 ± 7 | 174 ± 35** | 4.37 |

| Kp,uu,ECF (0–420) | 0.018 ± 0.003 | 0.042 ± 0.009* | 2.35 | |

| Kp,uu,ECF (0-inf) | 0.022 ± 0.003 | 0.058 ± 0.009* | 2.63 | |

| Brain CSF | ||||

| AUCu (0–420) | μg*min/mL | 39 ± 12 | 73 ± 27 | 1.88 |

| AUCu (0-inf) | μg*min/mL | 57 ± 15 | 117 ± 50 | 2.04 |

| Kp,uu,CSF (0–420) | 0.022 ± 0.006 | 0.024 ± 0.008 | 1.13 | |

| Kp,uu,CSF (0-inf) | 0.031 ± 0.007 | 0.039 ± 0.015 | 1.26 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6). A paired t-test was performed to compare cefadroxil parameters between the control (without probenecid) and treatment (with probenecid) phases of the study. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001. Abbreviations: AUC u, Area under the unbound concentration-time curve from time zero to 420 min (0–420) or from time zero to infinity (0-inf); C u,ss,blood, Unbound steady-state blood concentration; MRT iv, Mean residence time; t1/2, Half-life; CL, Total clearance; V ss, Volume of distribution steady-state; K p,uu,ECF, Ratio of AUCu in brain ECF to AUCu in blood; and K p,uu,CSF, Ratio of AUCu in CSF to AUCu in blood.

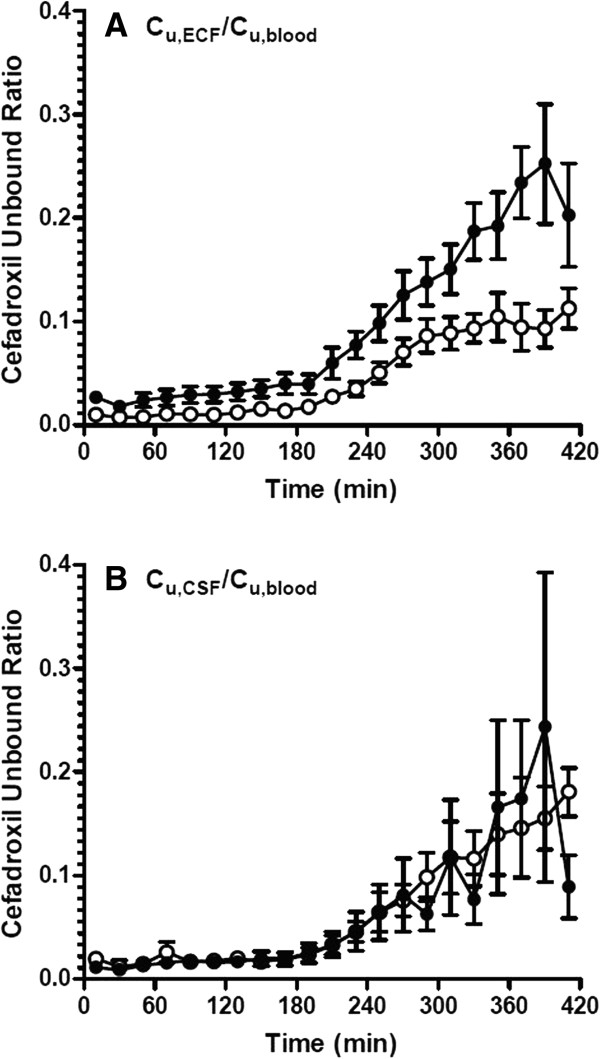

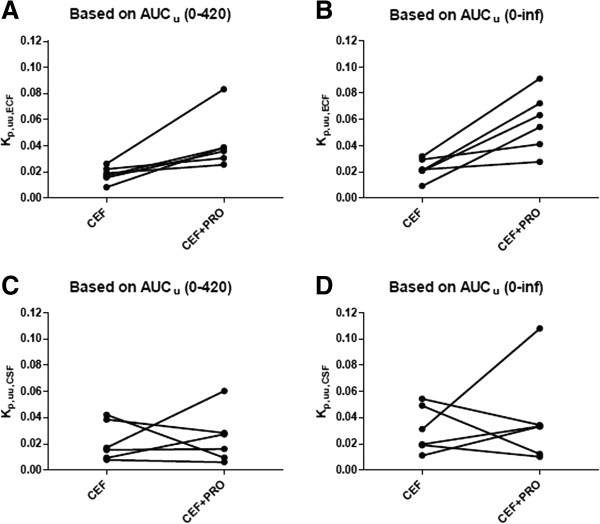

In addition to increasing unbound cefadroxil blood concentrations, probenecid increased the AUCu of drug in brain ECF 4-fold (p <0.05) and the AUCu of drug in CSF 2-fold (p >0.05) (Figures 1B and 1C, and Table 1). To determine if cefadroxil penetration into brain was affected by probenecid, brain drug concentrations were corrected by the corresponding values in blood (Figure 2). During probenecid infusion (Day 2), the Cu,ECF values of cefadroxil, relative to blood, were higher than control (Day 1) at all time points. In contrast, the Cu,CSF values of cefadroxil, relative to blood, were comparable. To evaluate the effect of probenecid on cefadroxil penetration into brain, the unbound partition coefficient Kp,uu was calculated for both brain ECF and CSF using AUCu values from 0–420 min and from 0-infinity (Figure 3). Kp,uu was around 0.02 in both brain ECF and CSF in the control situation, indicating limited penetration of cefadroxil into brain and extensive efflux at the BBB (Table 1). Kp,uu,ECF values were about 2.5-fold greater with probenecid treatment as compared to control. In contrast, there were no significant differences in Kp,uu,CSF between control and probenecid treatments. This may reflect, in part, greater experimental variability in the direction of change for this parameter (Figures 3C and 3D).

Figure 2.

The ratio of unbound cefadroxil in rat brain ECF (A) or CSF (B) to that in blood versus time. Open circles represent the results from Day 1 (no probenecid) and solid circles the results from Day 2 (with probenecid). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6).

Figure 3.

The unbound partition coefficient (K p,uu ) of cefadroxil in rat brain ECF (A, B) and CSF (C, D) for each of the six animals. CEF represents the study in which cefadroxil is given alone (Day 1) and CEF + PRO is when cefadroxil is given in the presence of probenecid (Day 2). See Table 1 for statistical analyses.

Microdialysis study of cefadroxil in the absence and presence of Ala-Ala

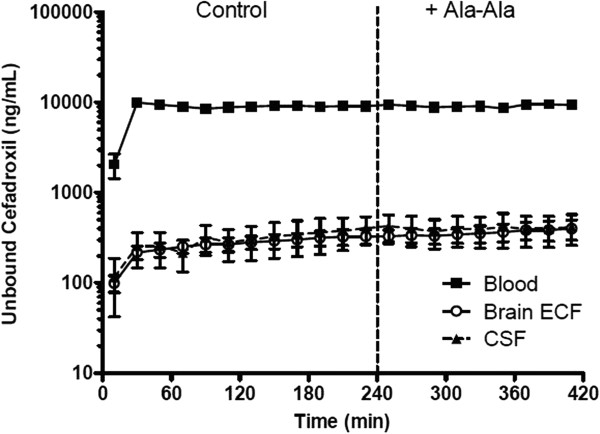

Recoveries were 16 ± 2%, 12 ± 1%, and 72 ± 1% for probes in the striatum, lateral ventricle and blood, respectively. Ala-Ala is a natural dipeptide that can be degraded in the body; thus, Ala-Ala was infused by the icv route in order to achieve high concentrations in CSF. The goal of the study was to determine if Ala-Ala affects the distribution of cefadroxil by comparing levels in ECF and CSF between vehicle control phase and during Ala-Ala infusions. As shown in Figure 4, the unbound concentrations of cefadroxil did not change substantially in brain ECF or CSF during Ala-Ala infusions. Furthermore, there was no significant difference between control and Ala-Ala infusions in Kp,uu,ECF (0.033 ± 0.004 to 0.041 ± 0.008, p = 0.15) or Kp,uu,CSF (0.038 ± 0.017 to 0.043 ± 0.016, p = 0.43).

Figure 4.

The concentration-time profiles of unbound cefadroxil in rat blood, brain ECF, and CSF in the absence and presence of Ala-Ala. Solid squares represent the results in blood, open circles the results in brain ECF, and solid triangles the results in CSF. The vertical dashed line separates the two treatment phases (CEF ± Ala-Ala). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 7).

In vitrobrain slice study

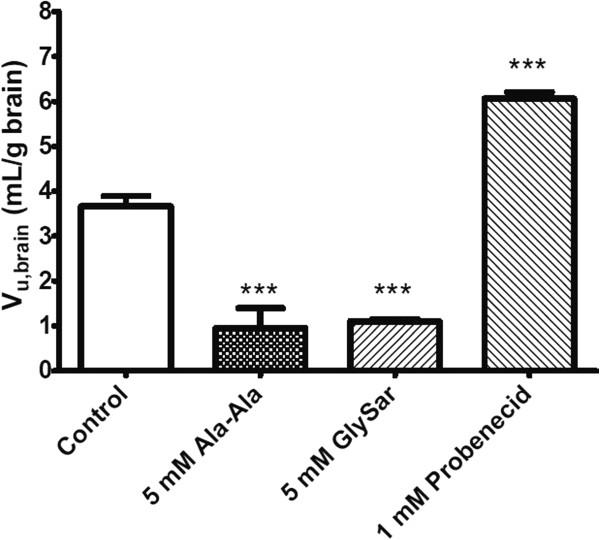

Vu,brain describes the relationship between the total amount of drug in brain and the unbound concentration of drug in ECF, and is useful as a measure of intra-parenchymal distribution [36]. A higher value Vu,brain suggests that more drug accumulates inside the brain cells. For control brain slices, the Vu,brain of cefadroxil was 3.67 ± 0.23 mL/g brain (Figure 5). Two PEPT2 substrates, Ala-Ala and GlySar, reduced the Vu,brain of cefadroxil to 0.95 ± 0.45 and 1.10 ± 0.05 mL/g brain, respectively, indicating that they reduced the accumulation of cefadroxil inside brain cells (p < 0.001). In contrast, probenecid increased the Vu,brain of cefadroxil to 6.06 ± 0.15 mL/g brain, suggesting that probenecid led to more accumulation of cefadroxil inside brain cells (p < 0.001).

Figure 5.

The unbound volume of distribution of cefadroxil (V u,brain ) in rat brain slices. Studies were performed with 0.8 μM cefadroxil alone (Control) and in the presence of inhibitors (Ala-Ala, GlySar and Probenecid treatments). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3-4). One-way ANOVA followed by the Dunnett’s test was performed to compare the inhibitor and control phases. ***p < 0.001 compared to control.

Discussion

The current study used microdialysis and brain slice methods to examine the transport mechanisms affecting the distribution of cefadroxil, a cephalosporin antibiotic, in brain. The results demonstrated that: 1) co-administration of probenecid increased blood cefadroxil levels; 2) probenecid markedly increased brain ECF cefadroxil concentrations; 3) the probenecid effect on brain ECF levels were partially due to increased blood concentrations but also due to inhibition of cefadroxil efflux at the BBB (OATs, OATPs and/or MRPs); 4) in contrast, increased CSF cefadroxil concentrations with probenecid were only due to elevated blood concentrations of antibiotic; 5) intracerebroventricular infusion of the PEPT2 substrate, Ala-Ala, did not increase brain ECF or CSF cefadroxil levels; and 6) brain slice experiments demonstrated that PEPT2 was involved in the uptake of cefadroxil into brain cells and that probenecid blocked a mechanism transporting cefadroxil out of cells.

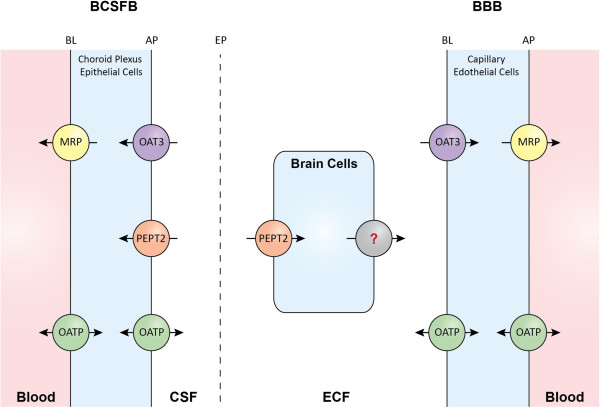

In the interaction study between cefadroxil and probenecid, intravenous co-administration of probenecid reduced the clearance of cefadroxil. This finding was consistent with previous studies [20, 25] showing that probenecid inhibits the renal secretion of many cephalosporins by OATs (and perhaps MRPs and OATPs) at the kidney proximal tubule [37]. Even though steady-state concentrations were achieved quickly for unbound cefadroxil in blood, steady-state concentrations in brain ECF were not fully reached within the infusion period of 3 hr. As a consequence, Cu,ECF decreased more slowly than Cu,blood after termination of the cefadroxil infusion. The above phenomenon may be due to low permeability of passive diffusion of cefadroxil at the BBB, considering its high hydrophilicity. The Kp,uu of brain ECF is determined by the net influx and efflux clearances at the BBB, as Kp,uu = CLin/CLout [36]. If only passive transport occurs at the BBB, Kp,uu is equal to unity due to the equal values for CLin and CLout. However, the Kp,uu,ECF of cefadroxil was about 0.02, indicating that cefadroxil CLout is much higher than CLin. Thus, it appears that there is net efflux transport for cefadroxil at the BBB. It has been reported that cefadroxil is a substrate of OATs and MRPs [6, 21, 22]. Specifically, OAT3 located at the basolateral (abluminal) side of the BBB and MRPs at the apical (luminal) side of the BBB mediate brain-to-blood transport as efflux transporters, thus possibly contributing the low Kp,uu,ECF of cefadroxil [13, 15, 38]. Inhibition of OAT3 and/or MRPs at the BBB is the probable reason why probenecid increased the Kp,uu,ECF of cefadroxil ~2.5 fold. In addition to OATs and MRPs, cefadroxil was reported to be a substrate of OATPs. However, OATPs are bidirectional transporters [12, 17, 18] and their net effect on cefadroxil transport at the BBB is unknown. A schematic representation of the membrane transporters involved in the CNS distribution of cefadroxil is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Membrane transporters (potentially) involved in the CNS distribution of cefadroxil. Several references were used to inform this schematic representation [16, 39–41]. There is much debate regarding the isoforms and membrane localization of MRPs at the BBB. There is, though, considerable evidence for some MRPs having an apical distribution clearing substrates to blood as depicted. There is also functional evidence for the probenecid-inhibitable efflux of cefadroxil from brain cells  , the nature of which is uncertain but may include OAT, MRP and/or OATP transporters. BL represents the basolateral membrane, AP the apical membrane, and EP the ependyma.

, the nature of which is uncertain but may include OAT, MRP and/or OATP transporters. BL represents the basolateral membrane, AP the apical membrane, and EP the ependyma.

OATs and MRPs [13, 14] are also responsible for the transport of substrates from CSF to blood at the BCSFB. Therefore, it was expected that inhibition of OATs and MRPs by probenecid would increase the Kp,uu,CSF of cefadroxil. However, no significant change was found for this parameter. The differential effect of transporter inhibition by probenecid on the distribution of cefadroxil in brain ECF and CSF may be related to the physiological and structural differences between BBB and BCSFB. The complement of efflux transporters, their expression levels, and cellular location may affect the relative importance of individual transporters in each of the two systems. In addition, the endothelial BBB is tighter than the epithelial BCSFB (choroid plexus), affecting paracellular diffusion [42]. A recent study on the effects of probenecid on methotrexate transport found a different modulation of methotrexate distribution in brain ECF and CSF [43]. There was a dose-dependent effect, in which probenecid increased the brain ECF-to-plasma ratio for two dose regimens of methotrexate (40 mg/kg and 80 mg/kg), whereas probenecid only significantly increased the CSF-to-plasma ratio at the higher dose [43]. The differential effects of probenecid on cefadroxil at the BBB and BCSFB in our study are unlikely to be due to differences in inhibitor concentration at the two sites as Deguchi et al. [44] found higher probenecid concentrations in CSF than ECF after systemic dosing.

In a previous study, PEPT2 ablation resulted in a marked increase in the CSF-to-blood concentration ratio of cefadroxil, indicating the importance of PEPT2 in eliminating cefadroxil from CSF at the BCSFB [20]. However, in the present study, an icv infusion of the PEPT2 substrate Ala-Ala did not significantly change CSF cefadroxil concentrations. This lack of effect may reflect insufficient concentrations of Ala-Ala reaching the BCSFB. Ala-Ala was chosen to inhibit PEPT2 because it has a relatively high affinity for that transporter (Ki = 6.3 μM, similar to that of cefadroxil with a Ki = 3.0 μM) [2]. However, Ala-Ala has the disadvantage of being degraded by peptidases, many of which are found in the choroid plexus and brain [45].

Vu,brain is a measure of drug distribution within brain parenchyma. The water volume in brain parenchyma is 0.8 mL/g brain and a Vu,brain of around 0.8 mL/g brain indicates a drug is distributed evenly through the whole brain tissue [36]. From a previous study using equilibrium dialysis in brain homogenate (data not published), cefadroxil had a fraction unbound (fu) of nearly 1, indicating little, if any, drug binding to brain tissues. This, together with the cefadroxil Vu,brain of 3.67 mL/g brain in the present study indicates the presence of uptake transporter(s) at the membrane of brain cells. The PEPT2 substrates, 5 mM Ala-Ala and GlySar, reduced the Vu,brain of cefadroxil, indicating that competitive inhibition of PEPT2 decreased the uptake of cefadroxil into brain cells. This is consistent with previous findings that PEPT2 is expressed on neurons and responsible for cellular uptake [46]. In contrast, probenecid increased the Vu,brain of cefadroxil, indicating there may also be efflux transporters (e.g., OATs, MRPs or OATPs) removing cefadroxil from brain cells. Interestingly, a previous study demonstrated that probenecid increased the intracellular levels of valproic acid by 1.5-fold in rabbit brain during in vivo microdialysis [47].

By using intracerebral microdialysis in vivo and brain slices in vitro, a better understanding was obtained about the effect of transporters on cefadroxil distribution in brain and, specifically, in brain extracellular and intracellular fluids, and CSF. From our study, it appears that transporters which are probenecid inhibitable (i.e., OATs, MRPs and/or OATPs) move cefadroxil in a vectorial direction from brain ECF to blood, and that PEPT2 transports cefadroxil into brain cells. In addition, as probenecid increased cefadroxil uptake into brain slices, there is an as yet unidentified cefadroxil transporter effluxing this cephalosporin from brain cells. It is concluded that multiple transporters play a role in the distribution of cefadroxil into and within the brain. The impact of these transporters on specific cephalosporins will depend on transporter affinities and drug levels in brain. Microdialysis is a useful tool to study the kinetics of unbound drug concentrations in ECF and CSF [48]. The brain slice method, together with other tools like equilibrium dialysis, provides an approach to study the distribution of drugs within brain after passing the BBB and BCSFB [34, 49].

A deeper understanding of the brain distribution of cephalosporins may aid in the better use of these antibacterial agents for the prophylaxis and treatment of CNS infections. Bacterial meningitis is an inflammatory process of the leptomeninges caused by bacterial infections. Bacterial meningitis is the most frequent CNS infection with a mortality rate approaching 20% [50]. It is believed that bacteria enter the CNS across BBB or BCSFB via transcytosis and finally enter the CSF [50]. Even though BBB permeability increases during meningitis [51], the barriers and their efflux transporters still play a role in limiting cephalosporin entry to brain. Clinically, the cephalosporins used for meningitis are limited to ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, and cefepime, which have high penetration into CSF [52]. Another CNS infection is cerebritis, a focal brain parenchyma infection, which is often followed by brain abscesses and permanent damage [53]. Treatment for cerebritis and brain abscesses also involves antibiotics. The strategy of blocking the related efflux transporters at the BBB and BCSFB is a promising way to enhance the penetration of relevant cephalosporins into brain ECF and CSF.

Probenecid was firstly widely used to decrease renal clearance of penicillin during World War II, when antibiotic supplies were low. Probenecid decreases the elimination rate and volume of distribution for a variety of medications including most cephalosporins [54]. However, with easier and cheaper production of antibiotics, probenecid is now seldom used with antibiotics. The present study showed that probenecid was able to increase the distribution of cefadroxil in brain ECF not only by reducing the renal clearance (and increasing systemic exposure) but also by specifically increasing the penetration into brain (i.e., increased Kp,uu) and further into brain cells. It should be appreciated that, although this study was not designed to study cefadroxil under clinical dosing conditions, the co-administration of probenecid allowed cefadroxil to reach the lower limit of its minimal inhibitory concentration in brain ECF for some bacteria (i.e., about 0.4 μg/mL). Thus, the combined therapy of cefadroxil (or perhaps other cephalosporins) and probenecid might be useful for some cases of meningitis and brain abscesses. Whether or not this approach is feasible would depend upon the extent of this drug-drug interaction in patients during different dosing combinations of both antibiotic and the inhibitor. Moreover, there is a delicate balance between the dose–response relationships of bacterial kill and CNS toxicity, which of course would have to be taken into account.

Conclusions

Using in vivo microdialysis and in vitro brain slice methods in rat, the present study demonstrated that probenecid increased cefadroxil distribution into brain extracellular and intracellular fluids by blocking related efflux transporters at the BBB and brain cells. Our findings suggest that the combination of probenecid and some cephalosporins may provide a strategy to increase therapeutic drug levels in brain for better treatment of CNS infections like bacterial meningitis and brain abscesses. On the other hand, since multiple transporters are involved in transporting cephalosporins in brain, there is also the potential for drug-drug interactions to enhance cephalosporin-induced neurotoxicity.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant R01-GM035498 (to DES) and by the Dr. Joan B. Kessler Award (a Rackham International Research Award) from the University of Michigan. The authors greatly appreciated the excellent technical support provided by Britt Jansson in the chemical analyses and by Jessica Dunhall in the animal experiments.

Abbreviations

- aECF

Artificial extracellular fluid

- CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid

- BBB

Blood–brain barrier

- BCSFB

Blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier

- CNS

Central nervous system

- POT

Proton-coupled oligopeptide transporter

- OAT

Organic anion transporter

- OATP

Organic anion transporting polypeptide

- MRP

Multidrug resistance-associated protein

- PEPT2

Peptide transporter 2

- CEF

Cefadroxil

- PRO

Probenecid

- GlySar

Glycylsarcosine

- AUC

Area under the curve

- t1/2

Half-life

- inf

Infinity

- CL

Clearance

- MRT

Mean residence time

- AUMC

Area under the moment curve

- Vss

Volume of distribution steady-state

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

XC contributed to the design of the study, carried out all experiments, performed data collection and analysis, and drafted the manuscript. IL participated in the brain slice study. MP participated in all experiments and data collection. RFK, DES, MHU contributed to the design of the study, data interpretation, and drafting of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Xiaomei Chen, Email: xmchen@umich.edu.

Irena Loryan, Email: irena.loryan@farmbio.uu.se.

Maryam Payan, Email: payan@razi.tums.ac.ir.

Richard F Keep, Email: rkeep@med.umich.edu.

David E Smith, Email: smithb@umich.edu.

Margareta Hammarlund-Udenaes, Email: mhu@farmbio.uu.se.

References

- 1.Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollmann BC. Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 12. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandsch M, Knutter I, Bosse-Doenecke E. Pharmaceutical and pharmacological importance of peptide transporters. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2008;60:543–585. doi: 10.1211/jpp.60.5.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burckhardt G. Drug transport by Organic Anion Transporters (OATs) Pharmacol Ther. 2012;136:106–130. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakakariya M, Shimada T, Irokawa M, Koibuchi H, Iwanaga T, Yabuuchi H, Maeda T, Tamai I. Predominant contribution of rat organic anion transporting polypeptide-2 (Oatp2) to hepatic uptake of beta-lactam antibiotics. Pharm Res. 2008;25:578–585. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9427-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakakariya M, Shimada T, Irokawa M, Maeda T, Tamai I. Identification and species similarity of OATP transporters responsible for hepatic uptake of beta-lactam antibiotics. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2008;23:347–355. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.23.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akanuma S, Uchida Y, Ohtsuki S, Kamiie J, Tachikawa M, Terasaki T, Hosoya K. Molecular-weight-dependent, anionic-substrate-preferential transport of beta-lactam antibiotics via multidrug resistance-associated protein 4. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2011;26:602–611. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.DMPK-11-RG-063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kato Y, Takahara S, Kato S, Kubo Y, Sai Y, Tamai I, Yabuuchi H, Tsuji A. Involvement of multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (Abcc2) in molecular weight-dependent biliary excretion of beta-lactam antibiotics. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36:1088–1096. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.019125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giacomini KM, Huang SM, Tweedie DJ, Benet LZ, Brouwer KL, Chu X, Dahlin A, Evers R, Fischer V, Hillgren KM, Hoffmaster KA, Ishikawa T, Keppler D, Kim RB, Lee CA, Niemi M, Polli JW, Sugiyama Y, Swaan PW, Ware JA, Wright SH, Yee SW, Zamek-Gliszczynski MJ, Zhang L. Membrane transporters in drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:215–236. doi: 10.1038/nrd3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abbott NJ, Patabendige AA, Dolman DE, Yusof SR, Begley DJ. Structure and function of the blood–brain barrier. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;37:13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abbott NJ. Blood–brain barrier structure and function and the challenges for CNS drug delivery. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2013;36:437–449. doi: 10.1007/s10545-013-9608-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saunders NR, Habgood MD, Dziegielewska KM. Barrier mechanisms in the brain, I. adult brain. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1999;26:11–19. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.1999.02986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kusuhara H, Sugiyama Y. Efflux transport systems at the blood–brain barrier and blood CSF barrier. In: DeBoer AG, editor. Drug Transport(ers) and the Diseased Brain. 1277. 2005. pp. 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartz AMS, Bauer B. ABC Transporters in the CNS - an inventory. Curr Pharm Biotechno. 2011;12:656–673. doi: 10.2174/138920111795164020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farthing CA, Sweet DH. Expression and function of organic cation and anion transporters (SLC22 family) in the CNS. Curr Pharm Design. 2014;20:1472–1486. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loscher W, Potschka H. Role of drug efflux transporters in the brain for drug disposition and treatment of brain diseases. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;76:22–76. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith DE, Johanson CE, Keep RF. Peptide and peptide analog transport systems at the blood-CSF barrier. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2004;56:1765–1791. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Westholm DE, Rumbley JN, Salo DR, Rich TP, Anderson GW. Organic anion-transporting polypeptides at the blood–brain and blood-cerebrospinal fluid barriers. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2008;80:135–170. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(07)80004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ronaldson PT, Davis TP. Targeted drug delivery to treat pain and cerebral hypoxia. Pharmacol Rev. 2013;65:291–314. doi: 10.1124/pr.112.005991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiang J, Chiang PP, Hu Y, Smith DE, Keep RF. Role of PEPT2 in glycylsarcosine transport in astrocyte and glioma cultures. Neurosci Lett. 2006;396:225–229. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen H, Ocheltree SM, Hu Y, Keep RF, Smith DE. Impact of genetic knockout of PEPT2 on cefadroxil pharmacokinetics, renal tubular reabsorption, and brain penetration in mice. Drug Metab Dispos. 2007;35:1209–1216. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.015263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khamdang S, Takeda M, Babu E, Noshiro R, Onozato ML, Tojo A, Enomoto A, Huang XL, Narikawa S, Anzai N, Piyachaturawat P, Endou H. Interaction of human and rat organic anion transporter 2 with various cephalosporin antibiotics. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;465:1–7. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(03)01381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Waart DR, van de Wetering K, Kunne C, Duijst S, Paulusma CC, Oude Elferink RP. Oral availability of cefadroxil depends on ABCC3 and ABCC4. Drug Metab Dispos. 2012;40:515–521. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.041731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia-Carbonell MC, Granero L, Torres-Molina F, Aristorena JC, Chesa-Jimenez J, Pla-Delfina JM, Peris-Ribera JE. Nonlinear pharmacokinetics of cefadroxil in the rat. Drug Metab Dispos. 1993;21:215–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Posada MM, Smith DE. Relevance of PepT1 in the intestinal permeability and oral absorption of Cefadroxil. Pharm Res. 2013;30:1017–1025. doi: 10.1007/s11095-012-0937-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marino EL, Dominguezgil A. The pharmacokinetics of Cefadroxil associated with probenecid. Int J Clin Pharm Th. 1981;19:506–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sugiyama D, Kusuhara H, Shitara Y, Abe T, Meier PJ, Sekine T, Endou H, Suzuki H, Sugiyama Y. Characterization of the efflux transport of 17beta-estradiol-D-17beta-glucuronide from the brain across the blood–brain barrier. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298:316–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luna-Tortos C, Fedrowitz M, Loscher W. Evaluation of transport of common antiepileptic drugs by human multidrug resistance-associated proteins (MRP1, 2 and 5) that are overexpressed in pharmacoresistant epilepsy. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58:1019–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ocheltree SM, Shen H, Hu Y, Xiang J, Keep RF, Smith DE. Mechanisms of cefadroxil uptake in the choroid plexus: studies in wild-type and PEPT2 knockout mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308:462–467. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.060400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang H, Hu Y, Keep RF, Smith DE. Enhanced antinociceptive response to intracerebroventricular kyotorphin in Pept2 null mice. J Neurochem. 2009;109:1536–1543. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06090.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiang J, Jiang H, Hu Y, Smith DE, Keep RF. Kyotorphin transport and metabolism in rat and mouse neonatal astrocytes. Brain Res. 2010;1347:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.05.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xie RJ, Bouw MR, Hammarlund-Udenaes M. Modelling of the blood–brain barrier transport of morphine-3-glucuronide studied using microdialysis in the rat: involvement of probenecid-sensitive transport. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;131:1784–1792. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bengtsson J, Bostrom E, Hammarlund-Udenaes M. The use of a deuterated calibrator for in vivo recovery estimations in microdialysis studies. J Pharm Sci. 2008;97:3433–3441. doi: 10.1002/jps.21217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loryan I, Friden M, Hammarlund-Udenaes M. The brain slice method for studying drug distribution in the CNS. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2013;10:6. doi: 10.1186/2045-8118-10-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Friden M, Ducrozet F, Middleton B, Antonsson M, Bredberg U, Hammarlund-Udenaes M. Development of a high-throughput brain slice method for studying drug distribution in the central nervous system. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:1226–1233. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.026377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huh Y, Keep RF, Smith DE. Impact of lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation on the disposition of the aminocephalosporin cefadroxil. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:6171–6178. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01497-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hammarlund-Udenaes M, Friden M, Syvanen S, Gupta A. On the rate and extent of drug delivery to the brain. Pharm Res. 2008;25:1737–1750. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9502-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giacomini KM, Huang SM. Transporters in drug development and clinical pharmacology. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;94:3–9. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2013.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahringer A, Ott M, Reimold I, Reichel V, Fricker G. The ABC of the blood–brain barrier - regulation of drug efflux pumps. Curr Pharm Design. 2011;17:2762–2770. doi: 10.2174/138161211797440221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keep RF, Smith DE. Choroid plexus transport: gene deletion studies. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2011;8:26. doi: 10.1186/2045-8118-8-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Redzic Z. Molecular biology of the blood–brain and the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barriers: similarities and differences. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2011;8:3. doi: 10.1186/2045-8118-8-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller DS. Top Med Chem. 2013. ABC transporters at the blood–brain barrier. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abbott NJ, Ronnback L, Hansson E. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood–brain barrier. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:41–53. doi: 10.1038/nrn1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Westerhout J, van den Berg DJ, Hartman R, Danhof M, de Lange EC. Prediction of methotrexate CNS distribution in different species - influence of disease conditions. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2014;57:11–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2013.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deguchi Y, Nozawa K, Yamada S, Yokoyama Y, Kimura R. Quantitative evaluation of brain distribution and blood–brain barrier efflux transport of probenecid in rats by microdialysis: possible involvement of the monocarboxylic acid transport system. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;280:551–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bourne A, Barnes K, Taylor BA, Turner AJ, Kenny AJ. Membrane peptidases in the pig choroid plexus and on other cell surfaces in contact with the cerebrospinal fluid. Biochem J. 1989;259:69–80. doi: 10.1042/bj2590069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shen H, Smith DE, Keep RF, Brosius FC., 3rd Immunolocalization of the proton-coupled oligopeptide transporter PEPT2 in developing rat brain. Mol Pharm. 2004;1:248–256. doi: 10.1021/mp049944b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scism JL, Powers KM, Artru AA, Lewis L, Shen DD. Probenecid-inhibitable efflux transport of valproic acid in the brain parenchymal cells of rabbits: a microdialysis study. Brain Res. 2000;884:77–86. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(00)02893-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hammarlund-Udenaes M. The use of microdialysis in CNS drug delivery studies - pharmacokinetic perspectives and results with analgesics and antiepileptics. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2000;45:283–294. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(00)00109-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Friden M, Gupta A, Antonsson M, Bredberg U, Hammarlund-Udenaes M. In vitro methods for estimating unbound drug concentrations in the brain interstitial and intracellular fluids. Drug Metab Dispos. 2007;35:1711–1719. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.015222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meli DN, Christen S, Leib SL, Tauber MG. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of meningitis caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2002;15:253–257. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200206000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tunkel AR, Scheld WM. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of bacterial-meningitis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6:118–136. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.2.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tunkel AR, Hartman BJ, Kaplan SL, Kaufman BA, Roos KL, Scheld WM, Whitley RJ. Practice guidelines for the management of bacterial meningitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1267–1284. doi: 10.1086/425368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Robbins SL, Cotran RS. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robbins N, Koch SE, Tranter M, Rubinstein J. The history and future of probenecid. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2012;12:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s12012-011-9145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]