Abstract

Biocompatible surfaces hold key to a variety of biomedical problems that are directly related to the competition between host-tissue cell integration and bacterial colonisation. A saving solution to this is seen in the ability of cells to uniquely respond to physical cues on such surfaces thus prompting the search for cell-instructive nanoscale patterns. Here we introduce a generic rationale engineered into biocompatible, titanium, substrates to differentiate cell responses. The rationale is inspired by cicada wing surfaces that display bactericidal nanopillar patterns. The surfaces engineered in this study are titania (TiO2) nanowire arrays that are selectively bactericidal against motile bacteria, while capable of guiding mammalian cell proliferation according to the type of the array. The concept holds promise for clinically relevant materials capable of differential physico-mechanical responses to cellular adhesion.

Nanoscale surface features and patterns underpin various biomedical applications1. Substantial progress achieved over the last decade in implant technologies and regenerative medicine emphasises the importance of surface topographies that can guide tissue development from the cell up2. Recent examples may include nanotubes and nanodots that mimic bone patterning and promote osteoblast adhesion and differentiation3,4,5 or microscopic grooves that show direct correlations with cell migration and alignment6,7,8. Major challenges remain in the provision of those patterns that are also capable of preventing bacterial adhesion and colonisation. Transplant medicine imposes particularly strict requirements for bacteria-free cell proliferation9. Concomitantly, the emergence of antimicrobial resistance compromises the use of traditional antibiotics10, prompting the need for alternative approaches11,12,13. A saving solution can be found in biological strategies that rely on physical rather than biochemical mechanisms of action. Cicada wings, Psaltoda claripennis, offer a notable lead14. Cicada wing surfaces are covered with dense patterns of nanoscale pillar structures that prevent bacterial fouling by rupturing individual cells15. Each pillar is approximately 200 nm tall, peaked with a spherical cap of 60 nm in diameter and separated from adjacent pillars at 170 nm distances. Such nanopatterns enable membrane poration in multiple sites tearing bacteria apart16. The mechanism is likely to be efficient at static and mechanical equilibria, but may also be less pronounced for more rigid membranes, which is partly confirmed for cicada wings shown to be selective against more elastic Gram-negative membranes15. However, synthetic nano-pillar protrusions do not necessarily discriminate bacterial adhesion on the basis of membrane elasticity17. In this respect, medically relevant cicada-like materials possessing appreciable bactericidal and cell-supporting properties may provide an efficient solution, but are lacking. Herein we introduce cicada-wing-inspired nanowire topographies that deter bacterial colonization while supporting the growth and proliferation of human osteoblast-like cells.

Results

Engineering titanium surface with titania nanowire arrays

Titanium is the material of choice for dental and orthopaedic implants. It meets all necessary criteria for biocompatibility and mechanical properties, but its smooth surfaces lack topographical cues that would be significant enough to influence cell adhesion in a specific manner18. At least partly for this reason, titanium is often surface-roughened to enhance the osseointegration of orthopaedic and dental implants19. Recently, it has been shown that titania nanodots as well as longer and intertwined nanowire structures can be produced to favour stem cell adhesion and differentiation20,21. Similar to mammalian cells, bacteria can adhere, colonise and disperse – processes that in principle can be influenced by analogous surface topographies. However, approaches relying on surface chemistry modifications remain to be most common. Typical examples include silver nanoparticle coatings, antimicrobial gels or polymer brushes22,23. Although efficient, all these materials are short of prolonged efficacy and often depend on active modifier concentrations and external stimuli. Potential antimicrobial resistance against chemical cues is of an additional concern. Encouraging evidence exists in support of bactericidal effects by water dispersions of single-walled carbon nanotubes13. By the analogy of surface patterns these physical agents are free-standing nanowires or nanopillars dispersed in solution. Yet, their ready incorporation and accumulation in circulating biological fluids and general cytotoxicity make their medical use impractical. By contrast, surface topographies are introduced and can be immobilised on a material surface and if made bactericidal would deter bacterial attachment only upon physical contact.

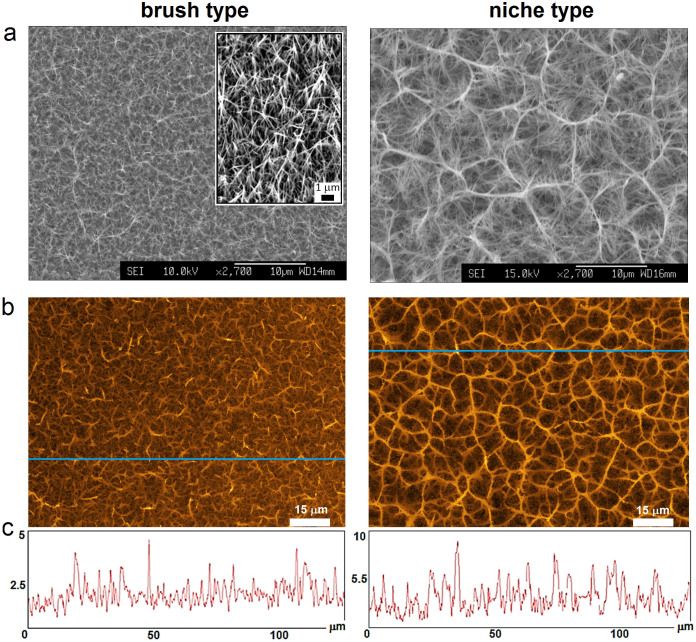

To provide such topographies, we engineered patterned titanium surfaces by applying an alkaline hydrothermal process as a function of time20. The method enabled the modification of titanium surfaces with controllable patterns of titania (TiO2) nanowires with a conserved diameter of ca. 100 nm. A three-hour hydrothermal treatment (240°C) was used to generate a homogenously dense coverage of spike-like structures with averaged heights of ca. 3 μm – a brush type (Fig. 1). A longer treatment, eight hours, produced longer structures that intertwined at their tips with the formation of dispersed niches or pockets – a niche type. These niches were ca. 10–15 μm in diameter and peaked at ca. 3 μm (Fig. 1). It should be noted here that within the timeframe of the hydrothermal treatments the topography of the background titanium surface does not change20,21.

Figure 1. Titania nanowire arrays.

Scanning electron (a) and confocal (b) micrographs of brush and niche type patterns. A 30° tilted view of (a) for the brush type showing sharp nanowire tips. (c) Height profile plots for the Z-stack blue areas (b) showing typical nanowire height distributions.

The resulting nanowires are an order of magnitude taller when compared with the nanopillars on cicada wings or black silicon15,16,17. In contrast to the short nanopillars, which can only porate membranes and may have little effect on bacterial adhesion in aggressive, dynamic and complex cellular environments, taller titania spikes have the capacity to pierce bacterial cells and resist extensive bacterial adhesion.

With this in mind, the two titania patterns, which differ only in their resulting topographies, were created to discriminate bacterial cell adhesion, by persistent nanowire coverage (brush type), and mammalian cell migration, between the isolated nanowire pockets (niche type).

The brush type is a disperse pattern of individual spikes that are capable of equally piercing bacterial and larger mammalian cells. Importantly, this pattern is sufficiently dense for mammalian cells to proliferate in a monolayer fashion as they do on flat surfaces, albeit with mechanically inhibited motility, which is in drastic contrast to much smaller bacterial cells that can be trapped in a nanowire array. Conversely, the isolated pockets in the niche type are meant to be easily colonised by bacteria, but are not sufficiently large to confine mammalian cells and arrest their spreading. Instead, these are envisaged to direct the migration of mammalian cells by engulfing their mobile edges, lamellipodia, without arresting cell proliferation.

Titania nanowire patterns are selectively bactericidal

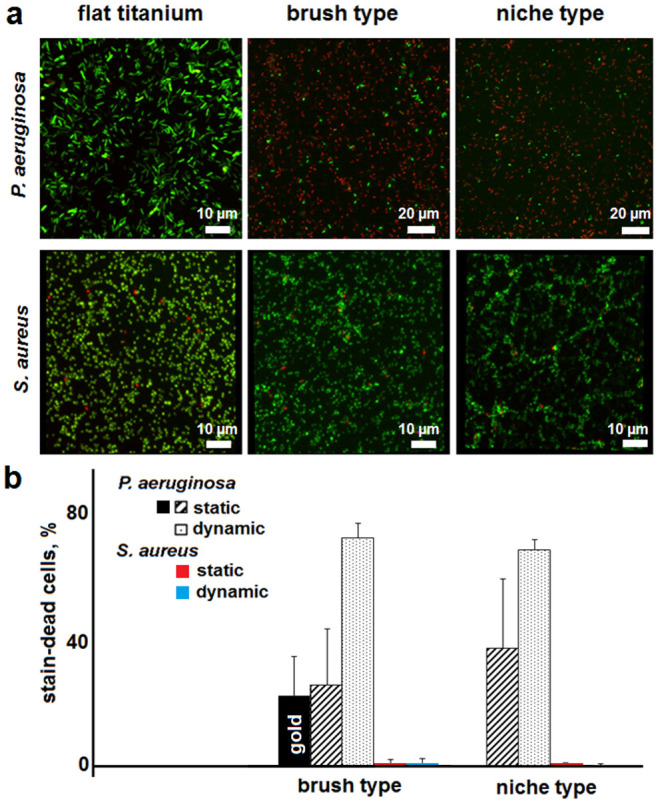

Consistent with the experimental rationale, the titania protrusions were found to be strongly bactericidal against P. aeruginosa. LIVE/DEAD® BacLight™ assays, which provide a measure of bacterial viability as a function of membrane integrity, showed comparable efficiencies for both surface types with clear cell-piercing effects (Fig. 2a,b). The results were comparable with those obtained for gold-plated patterns used as controls to mitigate potential contribution of residual photocatalytic oxidation on bacterial adhesion (Fig. 2b), thus confirming the physical nature of the bactericidal activity of the nanowires.

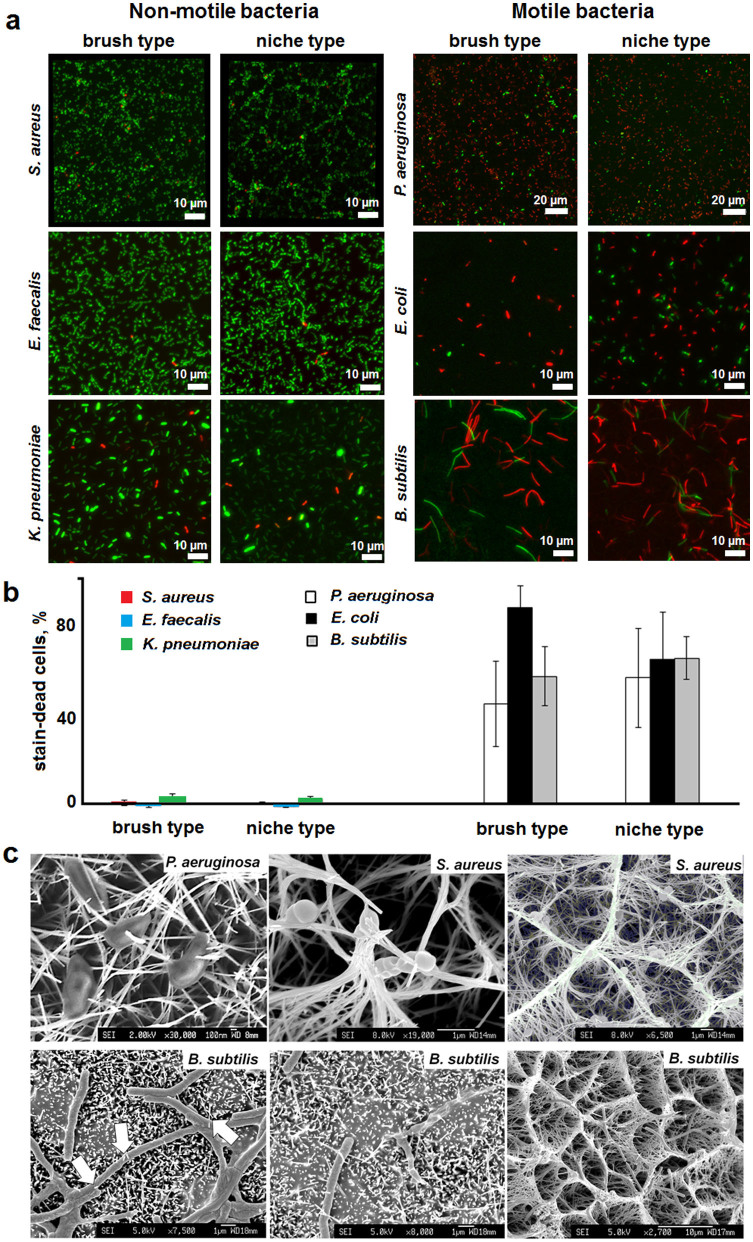

Figure 2. Bactericidal activity of nanowire titania surfaces.

(a) Fluorescence micrographs of P. aeruginosa and S. aureus after one-hour incubations on different surfaces. Bacterial viability LIVE/DEAD® BacLight™ assays simultaneously stain cells with intact (SYTO® 9, green) and damaged (propidium iodide, red) membranes. (b) Average number of stain-dead cells on nanowire surfaces, including gold-plated brush type (black bar), after subtracting the background adhesions (corresponding titanium and gold-coated flat surfaces).

In marked contrast, virtually no bactericidal activity was found against S. aureus under the same conditions; while cell-piercing was evident (Fig. 2b). Although these results were in good agreement with the earlier reports on the selectivity of cicada-wing pillars against Gram-negative bacteria15, further observations suggested an alternative mechanism for bactericidal selectivity.

P. aeruginosa, unlike S. aureus, is a highly motile bacterium, and may be more susceptible to different incubation conditions. Indeed, the bacterium was more resistant to the nanowire surfaces upon passive, static incubation conditions, than when incubated with agitation, dynamic conditions. Further, measurements performed on surfaces with nanowire arrays in the upright position gave somewhat stronger bactericidal effects than those in the upside-down position (Fig. 2c), while up to three-fold increases in efficiency were apparent for nanowires used in the upright positions and under dynamic conditions when compared to the values obtained without agitation. By contrast, only negligible differences held true for S. aureus which remained largely unaffected (Fig. 2c). Collectively, the data implies that pronounced bacterial motility may be associated with stronger bactericidal effects of the nanowire titania surfaces.

To probe this conjecture, other bacterial strains were incubated on the nanowire surfaces upright under static conditions, without agitation. Gram-negative, E. coli and K. pneumonia, as well as Gram-positive, B. subtilis and E. faecalis, bacteria were used. Based on their motility, these bacteria, together with P. aeruginosa and S. aureus, can be broadly categorised as motile – P. aeruginosa, E. coli and B. subtilis; and non-motile – S. aureus, E. faecalis and K. pneumonia.

Stain-dead bacterial viability assays revealed that none of the titania nanowire types was exclusively selective against Gram-negative bacteria. No obvious correlations of the responses with cell sizes were observed either. Instead, appreciable bactericidal activity was evident against motile cells (Fig. 3). Note should be taken here that the extent of adhesion on the nanowire and flat surfaces varied between the tested bacteria; while P. aeruginosa and S. aureus were strongly adhesive, B. subtilis tended to form less adherent floating pellicles. To address these differences and quantify bactericidal responses, the adhesion of S. aureus on flat titanium surfaces was taken as a control reference, which was subtracted from the adhesion of the other bacteria – S. aureus adhered to all of the tested surfaces with virtually the same efficiency and unaffected cell viability. Significant bactericidal activities resulting in >50% cell death within the first hour for motile bacteria proved to be comparable for both titania types whose nanowire patterns were sufficiently dense to discriminate bacteria as a function of motility (Fig. 3b). Consistent with this, no activity or negligible activity (K. pneumonia, <5% cell death) was observed for non-motile bacteria.

Figure 3. Bactericidal activity of nanowire titania surfaces.

(a) Fluorescence micrographs of bacterial cells incubated on different surfaces for one hour. Bacterial viability LIVE/DEAD BacLight™ assays simultaneously stain cells with intact (SYTO® 9, green) and damaged (propidium iodide, red) membranes. (b) Average number of stain-dead cells after subtracting the adhesion of S. aureus on flat titanium surfaces taken as a reference control. (c) Scanning electron micrographs of nanowire-pierced bacterial cells after one-hour incubations on both titania types (e.g. compare for B. subtilis) under dynamic conditions. White arrows point to exemplar piercing cites.

These results are notable in two regards. Firstly, cell-piercing, which occurred independently of motility, was only efficient against motile cells, that is, when combined with the retained ability of pierced cells to move. Secondly, granted the same effects on mammalian cells, which are larger and migrate in a more cooperative and directed manner, cell-piercing is likely to confine mammalian cell migration to monolayer proliferation. Indeed, subsequent studies using osteoblast-like cells (MG-63) confirmed this to be the case.

Titania nanowire arrays support different cell proliferation patterns

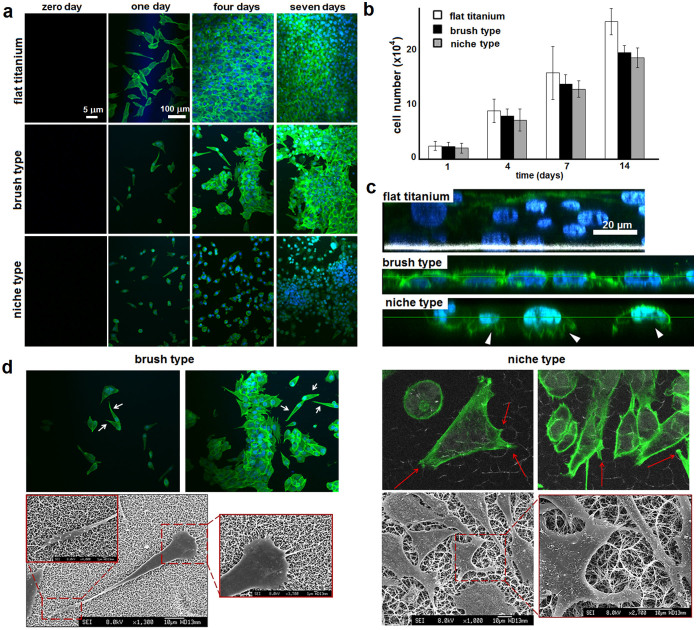

Specifically, the persistent nanowire coverage of the brush type appeared to arrest proliferation of individual cells, when compared to flat titanium, which remained in a monolayer phase over a week without significant changes thereafter (Fig. 4a). As gauged by fluorescence microscopy, the phase gradually developed from surface-fixed cells, day one, into monolayer clusters, by day four, which after several rounds of cell division evenly spread on the available area by day seven. In comparison, a cell monolayer established on flat surfaces by day four developed into a multilayer in subsequent three days (Fig. 4a), which suggests that nanowire arrays should support distinct cell proliferation patterns. Indeed, drastically different were cell responses on the niche type – cells appeared as individually isolated at day one and locally clustered by day four (Fig. 4a). The cells continued to proliferate within the formed clusters over a week without producing a continous monolayer. PrestoBlue® cell proliferation and viability assays, which give a quantitative measure of metabolically active cells, showed that cells on all the substrates remained viable over the course of two weeks (Fig. 4b). The cell viability results indicate that these differences in proliferation are not due to cytoxicity, but are a direct consequence of patterned proliferation defined by the array type.

Figure 4. Cell adhesion and proliferation.

(a) Fluorescence micrographs of MG-63 osteoblast-like cells on different surfaces. (b) Total viable cell count determined by the PrestoBlue® cell viability assay as a function of time. (c) Z-stack fluorescence images after seven-day incubations showing depth profiles of cell multilayers on flat titanium, continuous monolayers on the brush type and cell clustering on the niche type. White arrowheads point to lamellipodia. (d) Fluorescence (upper) and scanning electron (lower) micrographs showing distinctive cell morphologies after four-day incubations. White and red arrows highlight teardrop-shaped cells and lamellipodia reaching into the pockets, respectively.

Furthermore, the observed differences in proliferation patterns correlated with distinctive cell morphologies. While on the flat, non-restricting, surfaces cells were spread and elongated, as expected, cells on the brush type were dominated by a teardrop morphology, most likely reflecting a unipolar migration of cells that were physically held by the spikes. These observations are consistent with findings by others suggesting that persistent nanopillar-type patterns cause elongation of proliferating cells irrespective of their type, with examples including mesenchymal stem cells24, hepatic cells25 and fibroblasts26. By contrast, cells on the niche type tended to maintain their seemingly round and non-elongated shapes (Fig. 4a). Complementarily, images taken at different focus depths (z-stacks) confirmed mono- and multilayer formations for the brush and flat surfaces, while revealing localised proliferation for the niche type with clear evidence of lamellipodia formation, presumably in the pocket sites (Fig. 4c).

With additional evidence from scanning electron microscopy (SEM), both nanowire arrays proved to pierce cells at multiple sites (Fig. 4d, 5). However, unlike the relatively even brush-type coverage, at the cellular scale, the nanowire pockets of the niche type were able to direct cell migration. Upon adhering on to the surface, cells tended to reach and fill surrounding pockets with lamellipodia thereby promoting not only two-dimensional migration, as on the brush type, but also actively engaging the third dimension of pocket sites (Fig. 4d). This effect was particularly evident from the z-stack images (Fig. 4c). In comparison, the teardrop cell morphology supported by the brush type, which completely lacks potentially instructive niches, retained the elongated shape of individual cells, with their migration restricted to single lamellipodium formations (Fig. 4c, d and 5). This behaviour was supported by fluorescence time-lapse images acquired over 24 hours, which revealed that the attachment of an individual cell was immediately followed by one transient lamellipodium extension at a time to initiate migration (Video, white arrows). Evidence of cell division accompanying the phenomenon was also apparent, and confirms uncompromised cell viability despite the caused membrane damage (Video, blue arrows).

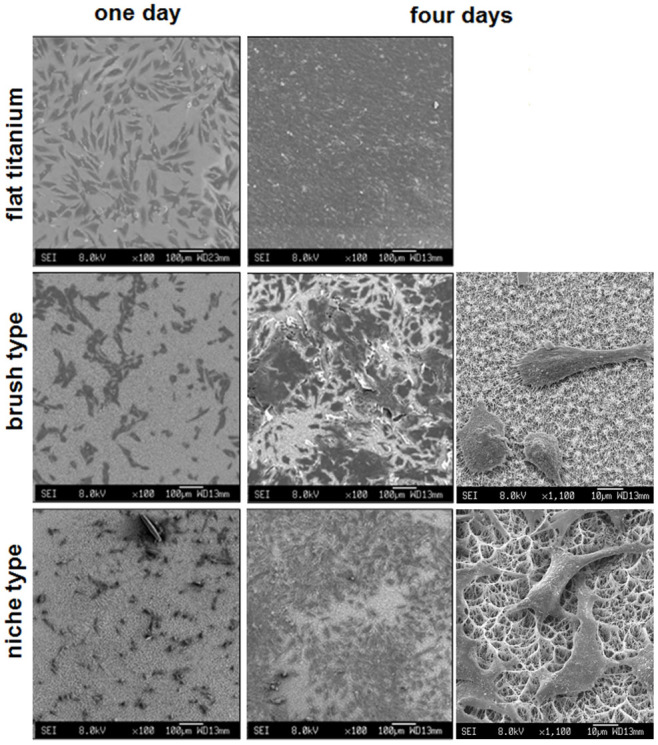

Figure 5. Cell adhesion and proliferation.

Scanning electron micrographs of MG-63 osteoblast-like cells on titanium and nanowire titania arrays after one and four days of incubation.

Taken together the results indicate that the nanowire arrays, and cell piercing by association, repel bacterial adhesion while supporting, as opposed to preventing, cell proliferation via distinguishable proliferation patterns correlated with the array type.

Discussion

Biocompatibility of materials is requisite for use in medical devices. Granted that their surfaces are chemically inert, the use is defined by altered surface chemistry or topography. Traditional approaches involve specialist molecular modifications or immobilisations, for example, polymeric hydrogels or hydrophobic films27,28,29, which can introduce anti-fouling properties. These approaches however do not differentiate between bacterial and mammalian cells and can equally resist the adhesion of both. Alternative strategies offer extracellular protein matrices that can be applied as soft surface coatings selectively promoting human cell proliferation while discriminating bacterial colonization30. Micro-to-nano-scale modulations of mammalian and bacterial cell adhesion by patterning can also have a differential impact on focal-adhesion formations due to differences in cell sizes31. Yet, permanent surface topographies which can be tailored to selectively discriminate cell adhesion and which can be used and re-purposed in one piece, potentially supporting the desired biological activity over long periods of time, are advantageous for implant technologies21. Natural surfaces such as those of insect wings appear to support this rationale with clear preference for physico-mechanical mechanisms of action, independent of chemistry32. In this regard, two types of engineered titania arrays presented in this study, persistent nanowire coverage (brush type) and isolated nanowire pockets (niche type), provide a promising avenue for designing physical patterns on titanium surfaces that are capable of discriminating one cell type, bacterial, from another, mammalian. Because such discrimination capitalizes on the mechanical and morphological, rather than structural or biochemical, properties of adhering cells, and because these arrays are readily fabricated using a straightforward process, potential applications are not limited by small surface areas and can be extended to essentially any type of biomedical implants, anti-fouling surfaces or biosensors.

Methods

Hydrothermal titania nanowire surfaces

Discs of 14 mm in diameter were cut from a titanium sheet (Titanium Metals Ltd) and polished to a mirror shine (TegraPol-15, Struers). The discs were then sonicated in acetone for 10 minutes, air-dried and slotted into custom-made PTFE holders to keep the discs upright before placing them into a 125 mL acid-digestion vessel (Parr Instrument Company) containing 1 M NaOH (60 mL). The vessel was tightly sealed and placed in an oven for 3 and 8 hours at 240°C. After the reaction, the discs were removed from the holders, rinsed with copious amounts of deionised water and treated at 300°C for 1 hour before immersion into 0.6 M HCl, to exchange sodium ions. The discs were then rinsed with water, placed in a furnace for calcination for 2 h at 600°C, sterilised with absolute ethanol and rinsed with sterile phosphate buffered saline prior to bacterial and cell culture studies. The smooth polished titanium discs were used as controls (flat titanium), and 10-nm gold-plated nanowire patterns were used as non-photocatalytic controls.

Bacterial culture and viability LIVE/DEAD® BacLight™ assays

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 27853), Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25723), Escherichia coli (ATCC PTA-10989), Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 6633), Enterococcus faecalis (OG1X) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (NCTC 5055) were used in this study. Glycerol stocks of bacteria were refreshed into 10 mL of Luria-Bertani for P. aeruginosa, E.coli and K. pneumonia, and nutrient broth for B. subtilis, brain heart yeast infusion broth for E. faecalis and tryptic soy broth for S. aureus for overnight incubation at 37°C prior to use (30°C for B. subtilis). 1 mL of the overnight growth was added to fresh respective broths and incubated until it has reached exponential growth. The suspension was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 min (Rotina 380R) and washed and harvested twice with 10 mM Tris HCl buffer at pH 7.00 (Sigma) and diluted to OD600 = 0.30 ± 0.03 with the Tris HCl buffer. The titanium discs were placed in 12-well plates and filled with 2 mL of the bacterial suspension before incubating for 1 h at 37°C (30°C for B. subtilis) in static conditions.

For dynamic conditions for P. aeruginosa and S. aureus, the plates were placed in an agitating incubator at 50 rpm, 37°C for 1 h. The titanium discs were held in the upright and upside-down orientations using a plastic clip. After incubation, the discs with surface-settled bacterial cells were rinsed and stained (0.13 μL of the stain added to 1 mL of Tris HCl) using a Live/Dead® BacLight™ bacterial viability kit (Invitrogen) for 15 min in the dark at room temperature and then rinsed with Tris HCl buffer. The chambers with discs were mounted on a confocal microscope for imaging. The amount of live and dead cells was counted using ImageJ (Z-stack images) and plotted as percentage of live cells.

Cell culture and seeding

All chemicals were from Sigma Aldrich unless stated otherwise. MG-63 human osteosarcoma cells were purchased from HPA culture collections. Cells were cultured in Minimal Essential Eagle's Medium (MEM) containing l% glutamine, 1% non-essential amino acids supplemented with heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (10%, v/v), and 0.2% gentamycin/amphotericin (all from Invitrogen, UK). Cells were maintained at 37°C under a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air humidity, and were seeded at 20,000 cells per disc sample, with the media changed twice weekly. All the cells were used between passage 11 and 18.

Fluorescence and viability probes

MG-63 cells on the discs were fixed for 15 min with formalin (Sigma) at room temperature, immersed in permeabilization buffer 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma) in phosphate buffer saline and incubated with AlexaFluor 488 phalloidin (Invitrogen) for 30 min at room temperature. The discs were flipped upside down onto ProLong® gold anti-fade reagent with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Invitrogen) in a chambered cover glass.

For viability studies the PrestoBlue® reagent (Invitrogen) was mixed with the cell medium in a 1:10 ratio, and 700 μL of the solution were dispensed into the wells containing the cells seeded on the discs. Following 1-h incubations at 37°C 100-μL aliquots were taken in quadruplicate from each well and placed into a 96 well plate. Fluorescence was then measured with a multi-label counter (Wallac Victor3 1420, Perkin Elmer) using 544-nm excitation and 590-nm emission filters. Standard calibration curves were generated by plotting measured fluorescence values versus cell numbers. For time-lapse imaging, cells (25 × 104) were incubated with CellLight® Actin-RFP, BacMam 2.0 reagent (50 μL) in a culture flask for over 18 hours at 37°C. The transfected cells were trypsinised and then seeded onto the discs for imaging overnight with 30-min intervals (Video).

Confocal microscopy

An Olympus LEXT OLS3100 confocal laser microscope was used to visualise the topography of the nanowire arrays. A Leica SP5-II confocal laser scanning microscope attached to a Leica DMI 6000 inverted epifluorescence microscope was used to visualise bacterial cells stained with the LIVE/DEAD® BacLight™ using a 100× objective under oil. With excitation at 488 nm, the SYTO® 9 (green) and propidium iodide (red) fluorescence emission was monitored at 515 nm and 625 nm, respectively. The morphology and coverage of MG-63 cells were visualised by the Olympus IX81 inverted confocal microscope using a 20× objective and a 60× objective under oil. A 488-nm laser was used for cytoskeleton and actin visualisation while a 633-nm laser was used to visualise titanium surfaces underneath.

Scanning electron microscopy

The discs rinsed with phosphate buffer saline before fixing cells, bacteria and MG-63, with 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.2 M sodium cacodylate for 2 h were dried with increasing gradients of 20, 40, 60 80 and 100% ethanol before drying with 25, 50, 75 and 100% v/v hexamethylsilizane (reagent grade ≥ 99%, Sigma) in ethanol. These samples were then mounted onto a stub and sputter coated with silver (high resolution sputter coater, Agar Scientific) for analysis on the JEOL 6330 FEG-SEM. Nanowire arrays were analysed without the need for sputter-coating.

Author Contributions

H.F.J., B.S. and M.G.R. designed the study. T.D., N.F., T.S. and B.L. performed the study. M.G.R. wrote the manuscript. All authors analyzed the data and contributed to the editing of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Video

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge funding from the EPSRC Case studentships (T.D.), the UK's Department of Business, Innovation and Skills and the Strategic Research Programme of the National Physical Laboratory. We thank Wolfson Bio-imaging Facility and Electron Microscopy Unit at the University of Bristol for their help with confocal and scanning electron microscopy, respectively.

References

- Mitragotri S. & Lahann J. Physical approaches to biomaterial design. Nat. Mater 8, 15–23 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon H.-J., Simon C. G. & Kim G.-H. Cell response to microscale, nanoscale, and hierarchical patterning of surface structure. J Biomed Mater Res B 102, 1580–1594 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S. et al. Stem cell fate dictated solely by altered nanotube dimension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 2130–2135 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N. et al. Effects of TiO2 nanotubes with different diameters on gene expression and osseointegration of implants in minipigs. Biomaterials 32, 6900–6911 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C.-H., Chen M.-H., Young T.-H., Jeng J.-H. & Chen Y.-J. Interactive effects of mechanical stretching and extracellular matrix proteins on initiating osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Biochem. 108, 1263–1273 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita S., Ohshima M. & Iwata H. Time-lapse observation of cell alignment on nanogrooved patterns. J Royal Soc Interf. 6, S269–S77 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton B. A. et al. Modulation of epithelial tissue and cell migration by microgrooves. J Biomed Mater Res. 56, 195–207 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walboomers X. F. & Jansen J. A. Cell and tissue behavior on micro-grooved surfaces. Odontology 89, 0002–0011 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B. et al. Soft tissue integration versus early biofilm formation on different dental implant materials. Dent Mater. 30, 716–727 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alanis A. J. Resistance to antibiotics: are we in the post-antibiotic era? Arch. Med. Res. 36, 697–705 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holban A. M., Gestal M. C. & Grumezescu A. M. New Molecular Strategies for Reducing Implantable Medical Devices Associated Infections. Curr Med Chem. 21, 3375–3382 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S., Herzberg M., Rodrigues D. F. & Elimelech M. Antibacterial Effects of Carbon Nanotubes: Size Does Matter!. Langmuir 24, 6409–6413 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S. et al. Sharper and Faster “Nano Darts” Kill More Bacteria: A Study of Antibacterial Activity of Individually Dispersed Pristine Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube. ACS Nano 3, 3891–3902 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan J. et al. Selective bactericidal activity of nanopatterned superhydrophobic cicada Psaltoda claripennis wing surfaces. Appl. Microb. Biotech. 97, 9257–9262 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova E. P. et al. Natural Bactericidal Surfaces: Mechanical Rupture of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Cells by Cicada Wings. Small 8, 2489–2494 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogodin S. et al. Biophysical Model of Bacterial Cell Interactions with Nanopatterned Cicada Wing Surfaces. Biophys. J 104, 835–840 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova E. P. et al. Bactericidal activity of black silicon. Nat Commun. 4, 2838 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Guehennec L., Soueidan A., Layrolle P. & Amouriq Y. Surface treatments of titanium dental implants for rapid osseointegration. Dent Mater. 23, 844–854 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anselme K. & Bigerelle M. Topography effects of pure titanium substrates on human osteoblast long-term adhesion. Acta Biomater. 1, 211–222 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjöström T. et al. Fabrication of pillar-like titania nanostructures on titanium and their interactions with human skeletal stem cells. Acta Biomater. 5, 1433–1441 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjöström T., McNamara L. E., Meek R. M., Dalby M. J. & Su B. 2D and 3D nanopatterning of titanium for enhancing osteoinduction of stem cells at implant surfaces. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2, 1285–1293 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L. et al. Antibacterial nano-structured titania coating incorporated with silver nanoparticles. Biomaterials 32, 5706–5716 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G. et al. Antibacterial surfaces based on polymer brushes: investigation on the influence of brush properties on antimicrobial peptide immobilization and antimicrobial activity. Biomacromolecules 12, 3715–3727 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucaro M. A., Vasquez Y., Hatton B. D. & Aizenberg J. Fine-tuning the degree of stem cell polarization and alignment on ordered arrays of high-aspect-ratio nanopillars. ACS Nano 6, 6222–6230 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi S., Yi C., Ji S., Fong C. C. & Yang M. Cell adhesion and spreading behavior on vertically aligned silicon nanowire arrays. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 1, 30–34 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W., Crouch A. S., Miller D., Aryal M. & Luebke K. J. Inhibited cell spreading on polystyrene nanopillars fabricated by nanoimprinting and in situ elongation. Nanotechnology. 21, 385301 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. et al. Broad-spectrum antimicrobial and biofilm-disrupting hydrogels: stereocomplex-driven supramolecular assemblies. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 52, 674–678 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostuni E. et al. Self-assembled monolayers that resist the adsorption of proteins and the adhesion of bacterial and mammalian cells. Langmuir 17, 6336–6343 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Cheng G. et al. Zwitterionic carboxybetaine polymer surfaces and their resistance to long-term biofilm formation. Biomaterials 30, 5234–5240 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faruqui N. et al. Differentially instructive extracellular protein micro-nets. J Am Chem. Soc. 136, 7889–7898 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. et al. Length-scale mediated differential adhesion of mammalian cells and microbes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 21, 3916–3923 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Hasan J., Crawford R. J. & Ivanova E. P. Antibacterial surfaces: the quest for a new generation of biomaterials. Trends Biotechnol. 31, 295–304 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video