Abstract

Osteoclasts (OC), specialized cells derived from monocytes, maintain skeletal homeostasis under normal conditions but degrade bone in patients with rheumatoid (RA) and psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Monocytes initially develop in the bone marrow (BM), circulate in peripheral blood, and differentiate into distinct cell types with diverse functions. Imaging studies in (RA) patients and murine arthritis models demonstrate that bone marrow edema detected on MRI is the result of enhanced myelopoiesis which precedes the development of bone erosions detected on plain radiographs several years later. A major knowledge gap, however, is whether OC develop in the BM and circulate to the joint and if the differentiation to OC takes place in the joint space in response to differentiation signals such as RANKL and TNF. We have previously demonstrated that osteoclast precursors (OCP) are increased in the circulaton of patients with RA and PsA. We showed that DC-STAMP (Dendritic Cell-Specific Transmembrane protein), a 7-pass transmembrane protein expressed on the surface of monocytes, is essential for cell-to-cell fusion during OC differentiation and is a valid biomarker of OCP. Herein, we examined OCP in human bone marrow and identified one novel subset of DC-STAMP+CD45intermediate monocytes which was absent in the blood. We also found that OCPs reside in human BM with a higher frequency than in the peripheral blood. These findings support the notion that the BM is a major reservoir of circulating OCPs. In addition, we demonstrated that a higher frequency of DC-STAMP+ cells in the BM have detectable intracellular IFN-γ, IL-4 and IL-17A than DC-STAMP+ cells circulating in the peripheral blood. Finally, the frequency of DC-STAMP+ monocytes and T cells is signficantly higher in PsA BM compared to healthy controls, suggesting an enhanced myelopoiesis is a central event in inflammatory arthritis.

Keywords: Osteoclasts, Monocytes, Myelopoiesis, Inflammatory arthritis

Introduction

Bone is a dynamic tissue that maintains homeostasis through continuous bone remodeling by bone-forming osteoblasts (OB) and bone-resorbing osteoclasts (OC) [1,2]. Bone houses the haematopoietic system and is the origin of many immune cells including monocytes and lymphocytes. Bone homeostasis can be profoundly disrupted by the innate and adaptive immune responses and the central importance of crosstalk between the immunocytes and bone cells is highlighted by an exciting new research field, osteoimmunology [3]. Results from osteoimmunology studies have unraveled complex mechanisms by which immune cells promote bone inflammation and destruction via actions on resident cells in the bone marrow (BM) [3]. The close relationship between the immune cells and bone is most evident in patients with inflammatory arthritis including rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) as evidenced by the following observations. First, bone marrow edema (BME) was detected by MRI in RA patients, findings which precede subsequent bone erosion by several years [4]. Second, bone marrow aspirates (BMA) are a great autologous source of osteoprogenitors containing stem cells with potential to regenerate bone that has been damaged by trauma or inflammatory arthritis [5]. Third, local bone inflammation was shown to promote osteoclast differentiation in the subchondral bone, indicating a functional role of BM as a matrix to promote local bone/joint damage [6].

Our research centers on the pathological and molecular mechanisms that underlie abnormal bone remodeling in PsA. Similar to RA, the majority of PsA patients develop bone erosions, leading to increased morbidity and decreased quality of life [7]. Psoriasis (Ps) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that affects 7.5 million Americans. Approximate 20-30% of Ps patients develop PsA charactized by joint and soft tissue inflammaton [7,8]. Our previous studies demonstrated that circulating OCPs are elevated in a subset of PsA patients and the frequency of these cells correlates with radiographic bone erosions [9]. To identify a biomarker of OCP that is expressed on the cell surface and can be identified by flow cytometry, we concentrated our studies on dendritic cell-specific transmembrane protein (DC-STAMP) [10,11], a seven-pass transmembrane protein which is required for multinucleated OC formation [12-14], for differentiation of myeloid cells [15], and for maintenance of immune tolerance [16]. Importantly, we demonstrated that DC-STAMP-expressing cells are elevated in PsA patients and showed a positive correlation between DC-STAMP+ monocytes and OCP frequency [17]. All of our previous studies were performed on cells isolated from the peripheral blood. In contrast to several lines of evidence demonstrating BM is involved in lymphoid neogenesis and in OC recruitment in RA [4,6,18], little is known regarding the role of the BM in OCP generation and its contribution to the pathogenesis of PsA. Several critical questions remain to be addressed: What are the interactions between OCPs in the peripheral blood and BM during the progression to PsA? Is there a positive correlation between OCP frequency in blood and BM? Do the elevated OCPs originate in the marrow or do they leave the marrow as monocytes, differentate into OCP, and become mature OC in response to signals expressed in the joint and/or lymph nodes [6]?

BME and lymphangiogenesis have been shown to play a critical role in inflammatory-erosive arthritis [19-21]. In the murine models of arthritis TNF-α transgenic mice, like humans with RA, showed BME on the joints by MRI. Histologic analysis of these lesions revealed prominent red marrow with little fatty change, increased myelopoiesis and elevated BM permeability [20], suggesting that the BM is a reservoir of inflammatory cells capable of degrading bone. In support of this interpretation was the finding that the majority of cells in the bone marrow lesions were CD11b monocytes. Intriguingly, BM has recently been shown to mirror the disease progression of Crohn’s disease (CD), an inflammatory bowel disease with granulomatous changes in the small and sometimes the large intestine [22]. Both PsA and CD belong to the Immune Mediated Inflammatory Disorders (IMIDs), a cluster of diseases characterized by over-production of Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) and the infiltration of target organs by inflammatory cells, leading to altered cell function and tissue pathology [23]. Studies of BM in these disorders are of interest, because TNF not only facilitates the trafficking of osteoclast precursors from the bone marrow to the lymphoid organs, but also renders them more susceptible to further differentiation into osteoclasts by inducing the receptors of key differentiation factors for osteoclasts, such as M-SCF and RANKL. When colitis was induced the murine model of CD, a rapid increase in monocytes and neutrophils was observed in BM, suggesting the myelopoiesis is an early event in inflammatory colotis [22]. Results from the CD study are clinically important, because they suggest that gut disorders can be potentially treated by reduction or alteration of the differentiation pathway in the BM.

Based on the enhanced myelopoiesis noted in the BM from the TNF transgenic arthritis model and from CD patients, , we surmised that the OCPs first develop in the bone marrow and after release, home to the joint where they undergo terminal differentiation to mature OC and erode bone. To address this paradigm, we expanded our research on DC-STAMP expressing cells from PBMC (Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell) to BM. Briefly, we identified a novel DC-STAMP+ monocyte subset in human BM which was absent in the blood, found an increased frequency of OCPs in BM, noted increased cytokine levels in DCSTAMP+ cells isolated from BM compared to blood, and observed an expansion DC-STAMP+ monocytes and T cells in PsA bone marrow compared to samples from healthy controls.

Materials and Methods

Study populations

Studies were carried out with the approval of the University of Rochester Medical Center Research Subjects Review Board. PsA was diagnosed based on the Moll and Wright Criteria [24].

Reagents

RANKL and MCSF were purchased from the R&D systems. Defined Fetal Bovine Serum was obtained from Hyclone. The fix & perm cell permeabilization reagents (Invitrogen) were used for intracellular staining of cytokines. Intracellular cytokine staininig was performed following vendor’s instructions for the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm Kit (BD Biosciences). The concentration of RANKL, M-CSF, IL-17, IL-23 for cell cultures were 100 ng/ml, 25 ng/ml, 100 ng/ml, and 200 ng/ml, respectively.

Cell staining and flow cytometry analysis

For flow cytometry analysis, cells were harvested, washed once with PBS, blocked with 5% normal mouse sera for 10 min at room temperature and stained with antibodies for 20 min. Cells were washed with PBS and fixed in 2% formaldehyde. FACS data were acquired using Canto or LSRII and analyzed using CellQuest (Becton Dickinson) or FlowJo (TreeStar) software.

Cell isolation from bone marrow and peripheral blood

All human subject studies were reviewed and approved by the Univeristy of Rochester IRB. Human bone marrow (BM) samples were collected from the ileac crest. BM cells were diluted by sterile PBS at 1:1 ratio before Ficol gradient separation. Monocytes were enriched by the Human Monocyte Enrichment Cocktail (StemCell) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Both BM and blood were processed following the PBMC isolation protocol published previously [17].

Characterization of OCP

Enumeration of OCP was carried out on purified monocytes as previously described [17,25]. One million monocytes were placed in eight-well chamber slides containing 0.5 ml 10% FCS-RPMI (Gibco, Grand Island, NY). Cultures were incubated in 6% CO2 at 37°C for 14 days in the absence of M-CSF and RANKL. Medium was replenished every 3 days. After 14 days, slides were stained for tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP; Sigma Diagnostics, St. Louis, MO) and viewed by light microscopy. TRAP-positive cells with ≥ 3 nuclei were counted as OC and scored as OC# per 106 monocytes. Cultures containing M-CSF (25 ng/ml) and RANKL (100 ng/ml) served as positive controls of OCP formation.

Statistics

Data analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 19 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests were carried out to verify Gaussian distribution of sampling means. Results were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Differences between experimental groups were tested using 2-tail paired t-test. The numbers shown below were mean ± standard deviation.

Results

Identification of a novel monocyte subset DC-STAMP+CD45intermediate in human bone marrow

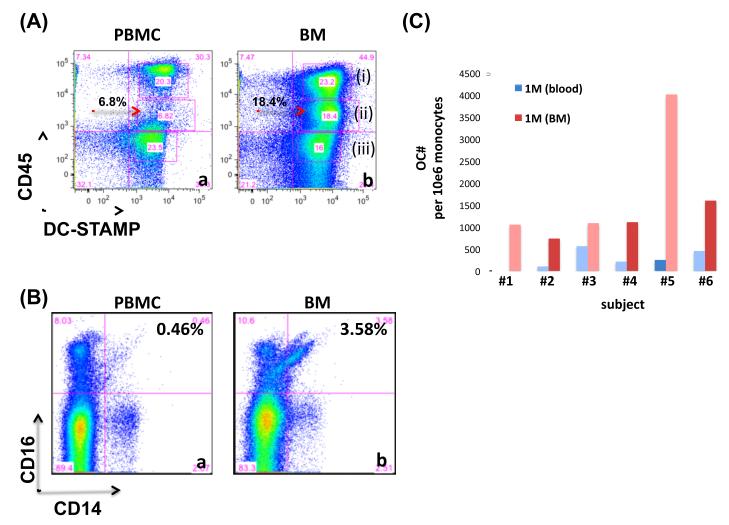

CD45 is an abundant receptor-linked tyrosine phosphatse that is expressed on all leucocytes and is required for efficient lymphocyte signaling [26-28]. The importance of CD45 is highlighted by the observation that CD45 is essential for lymphocyte development and signaling and that deficiency on CD45 is associated with SCID in humans [29]. We previously identified the presence of an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM) [17], on the cytoplasmic tail of DC-STAMP. Based on the abundace of CD45 on leukocytes and the tyrosine residue on the ITIM of DC-STAMP, CD45 is a candidate for the regulation of DC-STAMP-mediated signaling through phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. To this end, we examined the co- expression of CD45 and DC-STAMP on the cell surface. Based on the level of CD45 expression, DC-STAMP+ monocytes in human bone marrow could be separated into 3 subsets (Figure 1A and 1A-b(i) to 1A-b(iii)). Interestingly, one subset of the monocytes, DC-STAMP+CD45intermediate, was absent in the peripheral blood (red arrow in Figure 1(A)-a).

Figure 1.

(A) Identification of one CD14+ monocyte subset DC-STAMP+CD45int that is present in human bone marrow but absent in the peripheral blood. Monocytes isolated from bone marrow (BM) and peripheral blood (PBMC) were stained with an 11-color antibody cocktail and analyzed by flow analysis. CD14+ monocytes in PBMC (a) and BM (b) were analyzed by the cell surface expression of DC-STAMP (X-axis) and CD45 (Y-axis). The DC-STAMP+CD45int cell population was located by red arrows. Three cell populations DC-STAMP+CD45+, DC-STAMP+CD45int; and DC-STAMP+CD45− were labeled with (i), (ii), and (iii), respectively. Data shown were live cells after dead cells and doublet exclusion. Representative of 6 subjects including 3 healthy controls and 3 patients with psoriatic diseases.

(B) More non-traditional CD14+CD16+ monocytes reside in human bone marrow than peripheral blood. Cells were isolated from peripheral blood (a) and bone marrow (b), stained with one 11-color antibody cocktail, and analyzed by flow cytometry.

(C) Human bone marrow is the major reservoir of ostoeclast precursors (OCPs). Numbers of osteoclasts derived from enriched monocytes purified from human peripheral blood and bone marrow. Enriched monocytes were isolated from peripheral blood and bone marrow, cultured in OC-promoting media (RANKL+M-CSF) for 8 days, and TRAP-stained for OC enumeration. Enriched monocytes has a purity >80%.

Our previous studies showed that CD14+CD16+ monocytes are elevated in PsA patients and are the major reservoir of OCP [30]. Based on these observations, we compared the frequency of CD14+CD16− and CD14+CD16+ monocyte subsets in the compartments of peripheral blood and BM. As show in Figure 1B, human BM has a higher frequency of CD14+CD16+ monocytes than peripheral blood (3.58% vs. 0.46). To enumerate OCP in BM and peripheral blood, enriched monocytes were isolated from these 2 compartments and cultured in OC-promoting media (RANKL+MCSF) for 8 days followed by TRAP-staining. Figure 1C summarized the numbers of OC derived from 6 subjects. The average numbers of OC per million of enriched monocytes are 3,423 +/− 306 and 1.340 +/− 120 for BM and peripheral blood, respectively.

Characterization of the DC-STAMP+CD45intermediate monocytes in human BM

The phenotypes of the novel monocyte subset DC-STAMP+CD45int (red arrows in Figure 1A) present in BM but absent in the peripheral blood was further characterized. Three discrete DC-STAMP+CD45+ cell populations were identified (Figure 1(A), (i) to (iii)) and these subsets were analyzed with an antibody cocktail composed of the following hemopoietic markers: CD34, CD11b, and CD105. Figure 2 summarizes the expression of these markers on these 3 subsets of BM monocytes. Comparison of the expression of these hemopoietic markers on monocytes isolated from the peripheral blood (Supplemental Figure S1) revealed 2 unique cell subsets in the DC-STAMP+CD45int monocyte population (red arrows in Figure 2b and 2e). In contrast, no difference in the expression of these markers was detected on the other 2 cell subsets, DC-STAMP+CD45+ and STAMP+CD45− (Figures 2a, 2c, 2d and 2f) between BM and peripheral blood (Supplemental Figure S1, a, c, d, f). Thus, the CD34-CD11b+CD105-CD45intDC-STAMP+CD14+ monocyte subset was present only in the BM (red arrows in Figure 1A).

Figure 2.

Phenotypical characterization of DC-STAMP+CD45int monocytes in human bone marrow. Analysis of CD34, CD14, CD105 and CD11b expression on three distinct DC-STAMP+ cell populations (i, ii and iii shown in Figure 1A) separated by the expression level of CD45. Red arrows locate two cell populations absent in the peripheral blood (supplemental Figure 1).

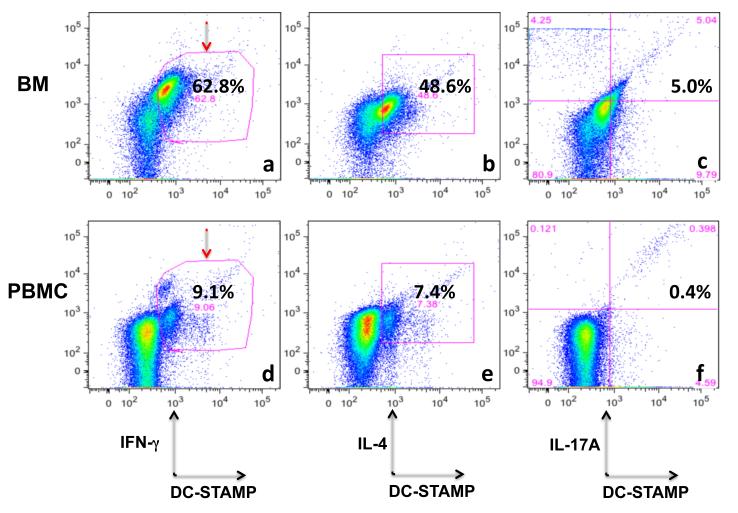

Elevated levels of intracellular cytokines in BM DC-STAMP+ cells

Elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines are observed in the BM of RA patients and anemia of chronic disease [31]. Mobilization of cells in BM, that home to the peripheral inflammatory sites or circulate into the blood, is also modulated by the inflammatory cytokines present in BM [32,33]. To evaluate the phenotype of DC-STAMP+ cells in BM, we examined three signature cytokines IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL17A associated with Th1, Th2 and Th17 polarization in BM. Figure 3 summarizes the frequencies of DC-STAMP+IFN-γ, DC-STAMP+IL-4+, and DC-STAMP+IL17A+, on total cells isolated from BM (Figures 3a-3c) and peripheral blood (Figures 3d-3f). The frequencies of IFN-γ+DC-STAMP+, IL-4+DC-STAMP+ and IL-17A+DC-STAMP+ cells in BM and PBMC were 62.8% and 9.1% (Figure 3a and 3d), 48.6% and 7.4% (Figure 3b and 3e), and 5.0% and 0.4% (Figure 3c and 3f), respectively. Of note, among three cytokines, the intracellular IFN-γ showed the highest elevation in DC-STAMP+ cells (62.8% in BM vs. 9.1% in PBMC, Figure 3a vs. 3d). Overall, the intracellular cytokine levels of IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-17A on DC-STAMP+ cells were higher in BM than peripheral blood (Figures 3a-3c vs. 3d to 3f), suggesting that BM is a major source of inflammatory effector cells in PsA.

Figure 3.

DC-STAMP+ cells in BM have a higher concentration of intracellular cytokines prominent in IFN-γ (red arrows) than DC-STAMP+ cells circulating in blood. Cells were isolated from bone marrow and intracellular cytokine staininig was performed following instructions provided by the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm Kit (BD Biosciences). Cells were stained with a 12-color antibody cocktail including anti-DC-STAMP, anti-IFNγ, anti-IL4 and anti-IL17A antibodies. Representative of 3 PsA patients.

Presence of DC-STAMP+ monocytes and T cells in BM and peripheral blood

OCPs are dramatically elevated in a subset of PsA patients and this increased frequency is associated with x-ray damage [9]. Currently, OC enumeration is based on the analysis of OCPs circulating in the peripheral blood [9,17]. It is unknown whether OCPs develop in the BM or at peripheral sites such as the lymph node or peripheral joint. Furthermore, if they do develop in the BM, the ability of these cells to recirculate between the BM and peripheral sites has not been carefully analyzed in inflammatory arthritis. Recent data showing that myelopoiesis is a critical event in murine models of arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease highlight the potential importance of understanding the role of the BM in disease pathogenesis. To this end, we examined the frequencies of DC-STAMP+ monocytes and T cells in the peripheral blood and BM in 3 HC and 3 PsA patients. Figure 4 summarizes the data on DC-STAMP+ cell subsets in these 6 subjects. On average, more DC-STAMP+CD14+ monocytes were found in the BM of PsA patients (Figure 4a vs. 4b, 30.1 +/− 10.8 vs. 8.9 +/− 5.2), whereas more DC-STAMP+CD3+ T cells were present in the BM of healthy controls (Figure 4c vs. 4d, 8.2 +/− 4.5 vs. 18.8 +/− 9.4). Of note, the distribution patterns of DC-STAMP+ T cells are significantly different between PsA and healthy controls (Figure 4c vs. 4d), suggesting that T cells regulation may be more of a peripheral event whereas OCP preferentially develop on the BM.

Figure 4.

Comparison of DC-STAMP+ cells between PsA patients and healthy individuals in the bone marrow. Cells were isolated from bone marrow and stained with a cocktail including anti-DC-STAMP, anti-CD14, and anti-CD3 antibodies. Data shown was after the exclusion of dead cells and doublets. Representative of 3 healthy controls and 3 PsA patients. (a) and (c): PsA patients, (b) and (d): HC. (a-b) CD14+ monocytes; (c-d) CD3+ T cells.

Discussion

Studies on BM have recently drawn the attention of musculoskeletal investigators because these cells possess the capacity for regeneration of bone after trauma or inflammation [5]. The BM also provides therapeutic potential because bone marrow aspirates (BMA) are an autologous source of stem cells including osteoprogenitors. In addition, many BM cells express a more naïve phenotype with the ability to differentiate into distinct lineages including immune and stromal cells. Differentiation of these distinct lineages can result in the formation of effectors that can remove or replace damaged bone [34]. Importantly, BM is also a reservoir of a diverse array of immune cells such as CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells that regulate cell trafficking and immune regulation [35]. The importance of the BM in the chronic inflammatory bone diseases is further highlighted by recent studies showing that BME on MRI in RA patients precedes the appearance of bone erosions mediated by OC [4,6,20]. Herein, we focused our studies on PsA and examined the phenotype DC-STAMP+ cells in human BM. In our previous studies, we showed that the DC-STAMP+ subset contains OCP in the peripheral blood [17]. Briefly, we identified and characterized a novel subset of monocytes, enumerated the frequency of osteoclast precursors (OCPs) in BM, examined intracellular cytokine production by DC-STAMP+ cells, and compared DC-STAMP+ populations between controls and PsA patients.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to characterize DC-STAMP+ cells in human bone marrow. Our findings are novel and important for the following reasons. First, we identified a unique monocyte population in human bone marrow (Figure 1A) which is absent from the peripheral blood. This finding suggests that this monocyte subset in BM may represent a source of OCP or alternatively, inflammatory monocytes. Second, we showed that the frequency of OCP and the precursor populations (DC-STAMP+CD14+ and CD14+CD16+ moncytes) are significantly higher in human BM than that in human peripheral blood (Figure 1C). Thus, the BM may be the major site of OCP generation although additional studies are required to formally examine this possibility. Simulataneous analysis of human bone marrow and inflammed synovial tissue in patients with RA and PsA will determine the major site of OCP generation in these disorders. Lastly, we demonstrated distinct cell distribution patterns of DC-STAMP+ monocytes and T cells in the BM of controls and PsA patients (Figure 4). These initial observations will be confirmed with additional analysis of bone marrow samples in controls and patients with RA and PsA. These findings underscore the central contribution of the BM environment to the generation of OCPs, the primary cells responsble for pathologic bone resorption [22].

The function of the DC-STAMP+CD45int monocyte subset identified in BM is unknown but several possiblities are under consideration. This population may be the reservoir of OCP and in this scenario, OCP mature from monocytes in response to RANKL expressed by osteoblasts and stromal cells in the bone marrow microenvironment. These cells may also represent a naïve monocyte subset or a monocyte subset which is undergoing transition similar to CD14+CD16int monocytes in the peripheral blood of PsA patients [30]. To address these two possibilities, sterile sorting of the DC-STAMP+CD45int monocytes for functional assays such as OC enumeration or Mixed Lymphocyte Assay (MLR) will be required. It will be also of interest to study the physical association between DC-STAMP and CD45 at different stages of OC differentiation by biochemical methods such as Western blotting. Since CD45 is a receptor-linked tyrosine phosphatase, it is likely to bind to the tyrosine residue on the ITIM of DC-STAMP to regulate signaling thru dephosphorylation. The expression of CD45 on the surface of DC-STAMP+CD45int monocytes might undergo internalization after dephosphorylation of tyrosine on DC-STAMP, which may take place only in BM due to the local cytokine and chemokine environment. Immunohistochemical characterization of subchondral bone marrow inflammatory infiltrates which contain these DC-STAMP+CD45int monocytes in eroded bone samples from PsA patients will be necessary to determine the in situ relationship between marrow inflammation and osteoclast recruitment. It is important to note that identification of a novel subset of monocyte population in human BM in this study is of importance, because knowledge of the function of these cells may improve the understanding of mechanisms that link inflammation in the BM and peripheral joint during the course of inflammatory arthritis.

The finding of an elevated levels of DC-STAMP+IL17A+, DC-STAMP+IL4+ and DC-STAMP+IFNγ+ cells in BM (Figure 3) is most intriguing given our current knowledge regarding the pathogenesis of PsA. In the current paradigm, inflammation is promoted by a Th1 and Th17 response [36]. Cytokines released during this combined immune response can trigger inflammation, bone erosion and possibly pathologic bone formation. Many targets can be envisioned including TNF, IL-23, IL-17, IL-17R and I-22. The presence of distinct cell frequencies of DC-STAMP+ monocytes and T cells in BM between healthy control and PsA patients (Figure 4) provide supportive evidence for the important contribution of the BM as a source of these cells. Based on our findings to date, fine dissection of cell populations in bone marrow using CyTOF analysis combined with genomics and proteomics to study the secretome [37] will provide invaluable insights into the mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of psoriatic diseases and reveal new therapeutic targets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all coordinators including Smith M, Moorehead S, Barrette R and Campbell D for patient recruitment and sample collection, Dr. Anolick and Dr. Looney for sharing the IRB protocol of human bone marrow collection. Fundings for this research are from National Institutes of Health AI78907, AR56702 and Janssen.

References

- 1.Rucci N, Takayanagi H. Editorial: bone and immune system cross-talk. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2012;11:169. doi: 10.2174/187152812800392779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Komatsu N, Takayanagi H. Inflammation and bone destruction in arthritis: synergistic activity of immune and mesenchymal cells in joints. Front Immunol. 2012;3:77. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zupan J, Jeras M, Marc J. Osteoimmunology and the influence of proinflammatory cytokines on osteoclasts. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2013;23:43–63. doi: 10.11613/BM.2013.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bugatti S, Manzo A, Caporali R, Montecucco C. Inflammatory lesions in the bone marrow of rheumatoid arthritis patients: a morphological perspective. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:229. doi: 10.1186/ar4115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dawson JI, Smith JO, Aarvold A, Ridgway JN, Curran SJ, et al. Enhancing the osteogenic efficacy of human bone marrow aspirate: concentrating osteoprogenitors using wave-assisted filtration. Cytotherapy. 2013;15:242–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bugatti S, Caporali R, Manzo A, Vitolo B, Pitzalis C, et al. Involvement of subchondral bone marrow in rheumatoid arthritis: lymphoid neogenesis and in situ relationship to subchondral bone marrow osteoclast recruitment. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3448–3459. doi: 10.1002/art.21377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ritchlin C. Psoriatic disease--from skin to bone. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2007;3:698–706. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiu YaR CT. Biomarkers to diagnose early arthritis in patinets with psoriasis. Psoriasis Forum. 2012;18:48–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ritchlin CT, Haas-Smith SA, Li P, Hicks DG, Schwarz EM. Mechanisms of TNF-alpha- and RANKL-mediated osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption in psoriatic arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:821–831. doi: 10.1172/JCI16069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kukita T, Wada N, Kukita A, Kakimoto T, Sandra F, et al. RANKL-induced DC-STAMP is essential for osteoclastogenesis. J Exp Med. 2004;200:941–946. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Staege H, Brauchlin A, Schoedon G, Schaffner A. Two novel genes FIND and LIND differentially expressed in deactivated and Listeria-infected human macrophages. Immunogenetics. 2001;53:105–113. doi: 10.1007/s002510100306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yagi M, Miyamoto T, Toyama Y, Suda T. Role of DC-STAMP in cellular fusion of osteoclasts and macrophage giant cells. J Bone Miner Metab. 2006;24:355–358. doi: 10.1007/s00774-006-0697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yagi M, Miyamoto T, Sawatani Y, Iwamoto K, Hosogane N, et al. DC-STAMP is essential for cell-cell fusion in osteoclasts and foreign body giant cells. J Exp Med. 2005;202:345–351. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yagi Mitsuru, Miyamoto Takeshi, Sawatani Yumi, Iwamoto Katsuya, Hosogane Naobumi, et al. DC-STAMP is essential for cell–cell fusion in osteoclasts and foreign body giant cells. JEM. 2005;202:345–351. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eleveld-Trancikova D, Janssen RA, Hendriks IA, Looman MW, Moulin V, et al. The DC-derived protein DC-STAMP influences differentiation of myeloid cells. Leukemia. 2008;22:455–459. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sawatani Y, Miyamoto T, Nagai S, Maruya M, Imai J, et al. The role of DC-STAMP in maintenance of immune tolerance through regulation of dendritic cell function. Int Immunol. 2008;20:1259–1268. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiu YH, Mensah KA, Schwarz EM, Ju Y, Takahata M, et al. Regulation of human osteoclast development by dendritic cell-specific transmembrane protein (DC-STAMP) J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:79–92. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bromley M, Woolley DE. Chondroclasts and osteoclasts at subchondral sites of erosion in the rheumatoid joint. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:968–975. doi: 10.1002/art.1780270902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papuga MO, Proulx ST, Kwok E, You Z, Rubery PT, et al. Chronic axial compression of the mouse tail segment induces MRI bone marrow edema changes that correlate with increased marrow vasculature and cellularity. J Orthop Res. 2010;28:1220–1228. doi: 10.1002/jor.21103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Proulx ST, Kwok E, You Z, Papuga MO, Beck CA, et al. Elucidating bone marrow edema and myelopoiesis in murine arthritis using contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2019–2029. doi: 10.1002/art.23546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwarz EM, Proulx ST, Ritchlin CT, Boyce BF, Xing L. The role of bone marrow edema and lymphangiogenesis in inflammatory-erosive arthritis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;658:1–10. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1050-9_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trottier MD, Irwin R, Li Y, McCabe LR, Fraker PJ. Enhanced production of early lineages of monocytic and granulocytic cells in mice with colitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:16594–16599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213854109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Firestein GS, Corr M. Common mechanisms in immune-mediated inflammatory disease. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2005;73:8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moll JM, Wright V. Psoriatic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1973;3:55–78. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(73)90035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liou SF, Hsu JH, Lin IL, Ho ML, Hsu PC, et al. KMUP-1 Suppresses RANKL-Induced Osteoclastogenesis and Prevents Ovariectomy-Induced Bone Loss: Roles of MAPKs, Akt, NF-κB and Calcium/Calcineurin/NFATc1 Pathways. 2013;8:7–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altin JG, Sloan EK. The role of CD45 and CD45-associated molecules in T cell activation. Immunol Cell Biol. 1997;75:430–445. doi: 10.1038/icb.1997.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bendall SC, Simonds EF, Qiu P, Amir el-AD, Krutzik PO, et al. Single-cell mass cytometry of differential immune and drug responses across a human hematopoietic continuum. Science. 2011;332:687–696. doi: 10.1126/science.1198704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang J, Siraganian RP. CD45 is essential for Fc epsilon RI signaling by ZAP70, but not Syk, in Syk-negative mast cells. J Immunol. 1999;163:2508–2516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tchilian EZ, Wallace DL, Wells RS, Flower DR, Morgan G, et al. A deletion in the gene encoding the CD45 antigen in a patient with SCID. J Immunol. 2001;166:1308–1313. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chiu YG, Shao T, Feng C, Mensah KA, Thullen M, et al. CD16 (FcRgammaIII) as a potential marker of osteoclast precursors in psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R14. doi: 10.1186/ar2915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jongen-Lavrencic M, Peeters HR, Wognum A, Vreugdenhil G, Breedveld FC, et al. Elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines in bone marrow of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and anemia of chronic disease. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:1504–1509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kallinikou K, Anjos-Afonso F, Blundell MP, Ings SJ, Watts MJ, et al. Engraftment defect of cytokine-cultured adult human mobilized CD34(+) cells is related to reduced adhesion to bone marrow niche elements. Br J Haematol. 2012;158:778–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geshi MSHSTKYOTSFTTSSKE. Inflammatory Cytokines Mobilize Bone Marrow Cells to Vascular Wall, Resulting in Neointimal Formation through Their Inflammatory Effects. Circulation. 2006;114 Abstract 1008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Du Rocher B, Mencalha AL, Gomes BE, Abdelhay E. Mesenchymal stromal cells impair the differentiation of CD14(++) CD16(−) CD64(+) classical monocytes into CD14(++) CD16(+) CD64(++) activate monocytes. Cytotherapy. 2012;14:12–25. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2011.594792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zou L, Barnett B, Safah H, Larussa VF, Evdemon-Hogan M, et al. Bone marrow is a reservoir for CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells that traffic through CXCL12/CXCR4 signals. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8451–8455. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raychaudhuri SP, Raychaudhuri SK, Genovese MC. IL-17 receptor and its functional significance in psoriatic arthritis. Mol Cell Biochem. 2012;359:419–429. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-1036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meissner F, Scheltema RA, Mollenkopf HJ, Mann M. Direct proteomic quantification of the secretome of activated immune cells. Science. 2013;340:475–478. doi: 10.1126/science.1232578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.