Abstract

Over half of the adults in Hawai‘i are overweight or obese, exposing them to increased risk for chronic diseases and resulting in higher health care expenses. Poor dietary habits and physical inactivity are important contributors to obesity and overweight. Because adults spend most of their waking hours at work, the workplace is an important setting for interventions to solve this growing problem. Changing the nutrition environment to support healthy eating is a recommended practice for worksite wellness interventions. Following this recommendation, the Hawai‘i State Department of Health (DOH) launched the Choose Healthy Now! Healthy Vending Pilot Project to increase access to healthy options in worksites. Choose Healthy Now! utilized an education campaign and a traffic light nutrition coding system (green = go, yellow = slow, red = uh-oh), based on federal nutrition guidelines, to help employees identify the healthier options in their worksite snack shops. Inventory of healthy items was increased and product placement techniques were used to help make the healthy choice the easy choice. DOH partnered with the Department of Human Services' Ho‘opono Vending Program to pilot the project in six government buildings on O‘ahu between May and September of 2014. Vendors added new green (healthy) and yellow (intermediate) options to their snack shop and cafeteria inventories, and labeled their snacks and beverages with green and yellow point-of-decision stickers. The following article outlines background and preliminary findings from the Choose Healthy Now! pilot.

Introduction

Obesity in Hawai‘i is prevalent and it is costly. The most recent data shows that in Hawai‘i, 23.6% of adults are obese, and another 32.5% are overweight, totaling 56.1% of adults with weight above recommended standards for their height.1 In 2009, the estimated annual direct medical care costs for obesity among adults in Hawai‘i was $470 million.2 Estimates of indirect costs, which include absenteeism, presenteeism (work lost due to illness when present on the job), and disability, vary based on methodology.3,4 Conservative estimates show $610 million in added costs, for a total of over $1 billion in obesity-related costs in Hawai‘i each year.3,4

For most adults in the United States, poor diet and physical inactivity are the most important contributors to overweight and obesity.5,6 Snacks and beverages play an important role in diet quality. According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), about one-third of calories consumed come from snacks.7 Many studies have shown that beverages, particularly sugar-sweetened beverages, have contributed to overweight and obesity.8,9 Healthy eating carries with it multiple benefits including decreased rates of chronic disease, overweight, and obesity, and improved overall health.5 Because adults spend the majority of their waking hours at work and often eat meals or snacks there, worksites represent an important area for public health interventions. The Community Guide to Preventive Services (The Community Guide) recommends implementing worksite nutrition and physical activity interventions, including informational and educational strategies, behavioral and social strategies, and policy and environmental approaches, to improve health outcomes related to obesity.10 In addition, the Hawai‘i Obesity Prevention Task Force Report identified worksites as a focus area, and recommended the formation of a work group to develop nutrition guidelines for food sold in vending machines, stores, and cafeterias, among other settings.11

In response to the growing obesity epidemic and recommendations from both The Community Guide and the Hawai‘i Obesity Prevention Task Force, the Hawai‘i Department of Health (DOH), Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Division, with funding provided through a cooperative agreement with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), launched the Choose Healthy Now! Healthy Vending Pilot Project. Choose Healthy Now! works by making evidence-based changes in the environment such as improved access, availability, and identification of healthier foods to support healthier eating.12–15 There is also evidence that traffic light labeling does not reduce revenue, which is important for the sustainability of this and similar projects.15 Using easy-to-understand labels (go, slow, and uh-oh), the project aims to enable customers to make informed choices on what they are purchasing and eating. The long-term goal is to bring worksite food and beverage environments into line with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans,5 and to transform social norms around food and beverage choices.

Theoretical Basis

Choose Healthy Now! is based on the social ecological model and the Analysis Grid for Environments Linked to Obesity (ANGELO) framework, which posit that a person's nutrition behaviors are influenced not only by individual factors, such as taste preferences, self-efficacy, and motivations, but also by a myriad of environmental factors: the social environment (eg, social norms, role modeling), the physical environment (eg, settings and the foods that are available in them), and the macro-environment (eg, food systems, advertising, prices).12,16–18 Addressing obesity at environmental levels has the potential to be more cost effective than individual approaches, as it can reach larger groups of people, can lead to systems changes that can be sustained over time,18 and does not require individuals to self-select into programs.19

Research has shown that modifications to the physical nutrition environment can improve eating behaviors in school settings.20 Although there is a gap in high-quality research studies of environmental modification interventions in worksites,12 one systematic review of thirteen worksite health promotion programs with environmental changes (including point-of- purchase labeling, increased availability of healthy foods, and use of promotional materials) showed a positive effect on employee diets with increased intake of fruits and vegetables, and decreased intake of fat.21

Simple labeling schemes such as the one used in this intervention (traffic light colors to indicate overall healthfulness of a snack or beverage) have been found to be an effective means to drive sales towards healthier items.13,15 Additionally, it was found that people who noticed the traffic light labels were more likely to purchase the healthier items than people who didn't notice them.13 The effectiveness of traffic light labels can been enhanced by choice architecture interventions, a strategy for making healthy choices more accessible through placement of healthy items at eye level, at the cash register, or making them more visible in other ways.15 With or without a choice architecture intervention, traffic light labels have been found to support sustainable improvements in healthful purchasing patterns and motivate employees from all racial and economic backgrounds to choose healthier items.14,15,22 Expanding the proportion of healthy snack choices in a snack shop (to 75% from 25%, in one study) is another way to increase selection of healthy choices without reducing employees' sense of freedom of choice.23 A study showed that even health-conscious customers often misidentify unhealthy choices as healthy and that customers' preference for healthy items increased once simpler nutrition information was provided.13 There is also evidence that the traffic light symbols do not reduce cafeteria or snack shop revenue.15 This is important when considering the sustainability of these interventions.

The Choose Healthy Now! Healthy Vending Pilot Project

DOH partnered with the Department of Human Services' Division of Vocational Rehabilitation Ho‘opono Vending Program (Ho'opono) to increase healthy options in snack bars and cafeterias in government buildings. Six vendors participated in the pilot project between May and September 2014. They represent snack shops in both state and federal buildings, with small, medium, and large operations. Vendors have been encouraged to continue carrying healthy items after September 2014. The lead Ho'opono vendor for the state, Kyle Aihara, said, “The vendors in our program pretty much all know someone with diabetes or heart disease. Vendors realize that offering healthier foods and beverages can help others to avoid these diseases. We also realize healthy vending is coming, and we need to stay ahead of the trend by increasing healthy foods and beverages now.” (Oral communication, August 11, 2014).

In preparation for the pilot project, an employee survey was distributed, via email and in-person, to government employees in the six worksite locations. The purpose of the survey was to gauge interest in having healthy options, to establish the current purchasing habits of employees, and to gather feedback on the types of healthy products employees would be willing to buy. The survey was distributed to approximately 1,350 people, with 436 people responding (an approximate response rate of 32%). The employee survey revealed that employees were most often visiting their worksite snack shops to purchase red items such as chips, candy and other sweets, and sugary drinks. However, respondents were interested in having healthy options available to them. Of the 436 respondents, 75% felt it was important for them to have healthy snacks available to them in their worksite snack shops and 76% reported they were willing to purchase those healthier items. In addition, when employees who did not regularly shop at the snack shop were asked to indicate why they did not shop, the top response was that they wanted healthier options. Employees' preferences for specific healthy products revealed by the employee survey were shared with vendors so they could bring in new products tailored to their customers' needs and preferences.

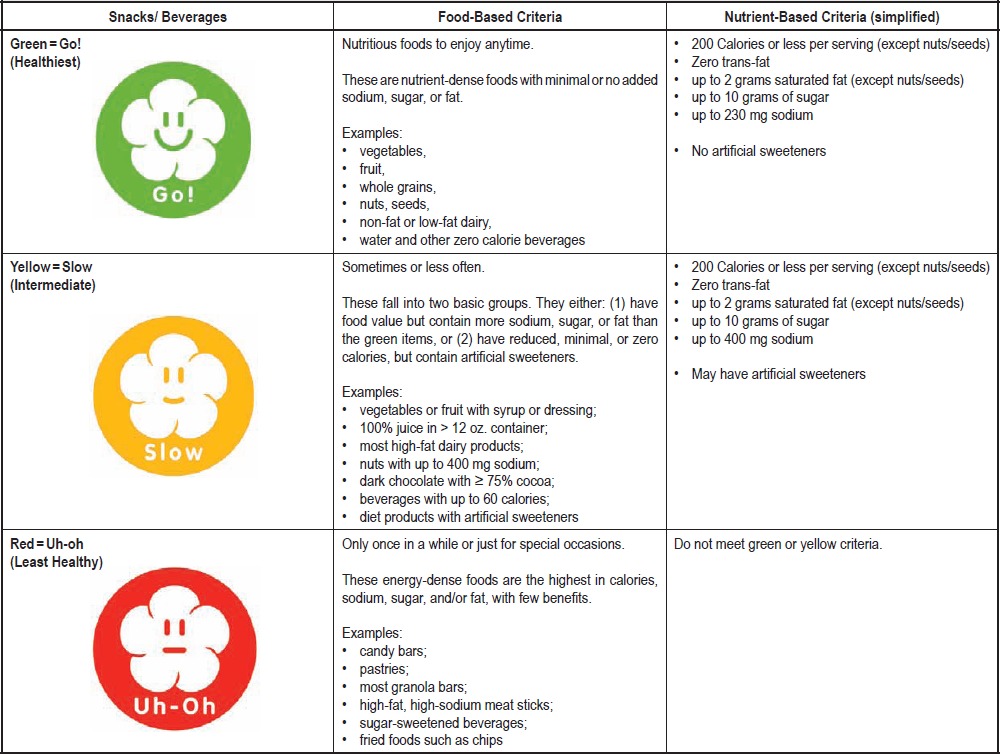

One of the first tasks of the project was to develop a nutrition-based rating system. Criteria were developed for pre-packaged snacks and beverages that have published nutrition and ingredient information. The Choose Healthy Now! criteria (Table 1) were developed by a registered dietitian and are based upon national standards set forth in the Health and Sustainability Guidelines for Federal Concessions and Vending Operations24,25 and the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans,5 and were modified to fit the availability of snacks and beverages in Hawai‘i. Snacks and beverages were subdivided into categories: green (healthiest), yellow (intermediate), and red (least healthy), corresponding with other uses of traffic-light ratings of foods such as “Go, Slow, Whoa” in US schools,26 and two similar worksite projects, the Iowa Department of Public Health Nutrition Environment Measurement Survey - Vending (NEMS-V) Project,27,28 and “Go for Green” developed by the US Army.29

Table 1.

Snack and Beverage Criteria used by Choose Healthy Now! Healthy Vending Pilot Project (Green, Yellow, Red)

|

Prior to the implementation of the pilot project, a baseline inventory of the snacks and beverages being sold in each of the participating locations was conducted using the Choose Healthy Now! criteria. Of the 960 items that were evaluated in the six snack shops, 7% were green, 21% were yellow, and 72% were red items. Given the impact of the nutrition environment on diet and the high percentage of unhealthy options available in workers' food environments, it is very likely that employees are consuming more energy-dense, nutrient-deficient foods relative to healthy, nutrient-dense foods. In fact, this was confirmed by the employee survey which showed that employees most often visit their worksite snack shops to purchase red items.

To aid employees in making healthier choices, point-of-decision stickers in green, yellow, and red were developed to nudge customers toward healthier options. In addition, materials, such as posters, signs, table tents, newsletters and emails were developed to educate employees about making healthy decisions, explain the meaning of the colored stickers, and promote the new healthy items in their worksite snack shops. All materials were designed with a Hawai‘i feel by a local graphic design firm. Before adoption, words and images were focus group tested with eight men and women from a variety of positions in multiple departments of DOH. Focus group feedback was used to revise the Choose Healthy Now! materials and ensure that they resonated with government employees. Once materials were modified, they were tested again among a random sample of 20–30 additional employees to ensure that they gave the intended message.

Posters (Figure 1) were placed throughout the buildings in high traffic areas with the suggestion that people “check out the new healthy choices” at their cafeteria or snack bar. Posters inside the cafeteria encouraged employees to “choose green.” Signs and table tents (Figure 2) were used to educate employees on the meaning of the colored stickers. Newsletters and emails were adapted from the Iowa NEMS-V online materials.30 During the 12-week pilot, a total of 6 emails, each with a newsletter attachment, was sent out to educate staff about nutrition and to remind them to select healthy snacks and beverages in support of their vendor's efforts. Incentive cards were offered that enabled customers to receive 1 free green item for every 7 green items they purchased. Four out of six vendors decided to use the incentive cards to encourage employees to purchase green items. Other incentive items (green chopsticks and green lanyards, each with the Choose Healthy Now! logo) were provided free to vendors to pass out with the purchase of a green item during the first days and weeks of the campaign to encourage early participation by employees.

Figure 1.

Example posters from Choose Healthy Now!

Figure 2.

Example educational sign from Choose Healthy Now!

The Choose Healthy Now! Healthy Vending Project launched in May 2014 with a press event where pilot vendors were recognized for their initiative and participation. Vendors were encouraged to add 5–10 new green and yellow products to their inventory for the pilot project, and many added more than that. Vendors chose new products that both fit with their business models, and met the needs and preferences of the employees in their buildings, as revealed by the employee survey. By the public launch of the pilot project, on average, vendors had increased the number of green products they were selling by 128% and the number of yellow products by 10%. To encourage sales of healthier items, green and yellow products in each snack shop were stickered with the point-of-decision prompts and, wherever possible, given prime placement at eye-level to encourage purchasing.15,31 During the project, green and yellow 1-inch round stickers were placed in front of healthiest and intermediate items, respectively. However, because the vendors were concerned about discouraging purchases of their top selling red items, they chose not to use red stickers, so the least healthy items were left undesignated. In addition to the distribution of promotional and educational materials, each snack shop had a kick-off event, where employees were able to sample the new products, learn about the Choose Healthy Now! coding system, and receive an incentive item for purchasing healthy items.

A variety of evaluation methods are being utilized to assess the outcomes of the project. The project will be evaluated for its impact on snack and beverage choices in work environments, and to see what changes occurred in vendors' total snack shop revenue. Exit surveys will be conducted at each of the snack shops to ascertain the effectiveness of the point-of-decision prompts on employee purchases. Data from exit surveys will be used to revise messaging in order to improve awareness of the stickers and healthy items. One of the goals of Choose Healthy Now! was to see that vendors' revenue was maintained or increased to ensure that the changes are sustainable. Because vendor cash registers do not have the capacity to track sales of individual products, each snack shop's total sales during the pilot project will be compared with the same period of time in the previous year. In addition, vendors will be interviewed on their experience with the project to assess vendor perceptions of the campaign's impact, and to gather feedback to improve the campaign moving forward.

Next Steps

At the end of the 12-week pilot, participating vendors were encouraged to continue with Choose Healthy Now! As evaluation data is analyzed, efforts are being directed towards improving and expanding the project. Work will continue on identifying and increasing the number of offerings of healthy foods and beverages from warehouse stores and distributors that sell to retail snack shops and cafeterias. Choose Healthy Now! will also focus on recruiting participation from additional Ho‘opono vendors, with special emphasis on engaging those on the neighbor islands. Expansion to private businesses and other worksites is already in progress. Castle Medical Center (CMC) on O‘ahu, is adopting Choose Healthy Now! beginning with items offered in their employee and visitor cafeteria. CMC is in the process of rolling out the campaign with snacks and beverages and will be expanding to other foods, such as entrees, side dishes, soups, and salads, as criteria for such foods are developed. They will be using all three of the colored stickers, green, yellow, and red to mark foods and beverages.

Using the lessons learned from this project, a toolkit will be developed and published online that will give employers access to the marketing materials, simplified criteria for healthy foods and beverages, and model policy for offering healthy foods and beverages in public and private worksites. The toolkit will be made available to use free-of-charge. The project collaborators hope that businesses will not only implement Choose Healthy Now! but also adopt policies that ensure that access to healthy foods and beverages will be sustained in worksites statewide.

Conclusion

Addressing obesity and chronic disease with environmental changes has the potential to reach a broader audience at lower cost overall than programs targeting individuals, and the benefits are more likely to be sustained over time. Promising practices to improve employees' diets include expanding the inventory of healthy foods and beverages in worksite settings, and identifying and highlighting those healthy items with point-of-decision prompts and product placement. Choose Healthy Now! utilized these strategies to modify the nutrition environment in government buildings on O‘ahu and used marketing and nutrition education to promote the purchase and consumption of healthy snacks and beverages. The data analysis at the end of the pilot will be shared and will be used to inform the direction of Choose Healthy Now! as it adds new government worksites and expands into food vending sites in private businesses. More research is needed in Hawai‘i to confirm the effectiveness of strategies currently in use, to identify worksites that will benefit most from a similar intervention, and to identify new worksite wellness strategies that will support healthy eating.

For further information, contact Carolyn Donohoe-Mather at carolyn.donohoemather@doh.hawaii.gov or (808) 586-4526, or write her at the Hawai‘i State Department of Health, Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Division, P.O. Box 3378, Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96801-3378.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the many individuals who helped to make Choose Healthy Now! a successful project and contributed to this article. Specifically, we would like to recognize the vendors and operational staff of the Ho‘opono Program who volunteered to be a part of this project and supported it during the piloting phase. The authors would also like to thank Lola Irvin, Tonya Lowery St. John, Ranjani Starr, Heidi Hansen-Smith, Katie Richards, and Jay Maddock for their feedback and review of this article. Finally, special thanks go to Mary Goldsworthy and Heide Pescador for their assistance in the early stages of the Choose Healthy Now! project, and for their work in identifying articles for the literature review.

Contributor Information

Jay Maddock, Office of Public Health Studies at John A Burns School of Medicine.

Donald Hayes, Hawai‘i Department of Health.

References

- 1.Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, author. Hawai‘i Data BMI Status 2012. 2012. [August 20, 2014]. http://www.hhdw.org/cms/uploads/Data%20Source_%20BRFFS/Weight/BRFSS_Weight%20Control_IND_00001_2011.pdf.

- 2.Trogdon JG, Finkelstein EA, Feagan CW, Cohen JW. State- and payer-specific estimates of annual medical expenditures attributable to obesity. Obesity. 2012 Jan;20(1):214–220. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammond RA, Levine R. The economic impact of obesity in the United States. Diabetes, Metab. Syndr. Obes. Target Ther. 2010;3:285–295. doi: 10.2147/DMSOTT.S7384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dee A, Kearns K, O'Neill C, Sharp L, Staines A, O'Dwyer V, Fitzgerald S, Perry IJ. The direct and indirect costs of both overweight and obesity: a systematic review. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7(242):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), author 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 7th ed. 2010. [August 14, 2014]. http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/dgas2010-policydocument.htm.

- 6.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), author The Surgeon General's call to action to prevent and decrease overweight and obesity. Rockville, MD: 2001. [August 14, 2014]. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44210/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bliss RM. Snacking associated with increased calories, decreased nutrients. [August 14, 2014]. http://www.ars.usda.gov/is/pr/2012/120312.htm. Updated March 2012.

- 8.Hu FB. Resolved: there is sufficient scientific evidence that decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption will reduce the prevalence of obesity and obesity-related diseases. Obesity Rev. 2013;14(8):606–619. doi: 10.1111/obr.12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malik VS, Pan A, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(4):1084–1102. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.058362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guide to Community Preventive Services. Obesity prevention and control: worksite programs. [August 14, 2014]. http://www.thecommunityguide.org/obesity/workprograms.html. Updated September 2013.

- 11.State of Hawai‘i Department of Health, author. Report to the 27th Legislature State of Hawai‘i: Recommendations from the Childhood Obesity Prevention Task Force. 2013. [August 14, 2014]. http://co.doh.hawaii.gov/sites/LegRpt/2013/Reports/1/ACT%20269.pdf.

- 12.Brug J. Determinants of healthy eating: motivation, abilities and environmental opportunities. Fam Pract. 2008;25(Suppl 1):i50–i55. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sonnenberg L, Gelsomin E, Levy DE, Riis J, Barraclough S, Thorndike AN. A traffic light food labeling intervention increases consumer awareness of health and healthy choices at the point-of-purchase. Prev Med. 2013;57(4):253–257. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thorndike AN, Sonnenberg L, Riis J, Barraclough S, Levy DE. A 2-phase labeling and choice architecture intervention to improve healthy food and beverage choices. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(3):527–533. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thorndike AN, Riis J, Sonnenberg LM, Levy DE. Traffic-light labels and choice architecture: promoting healthy food choices. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(2):143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larson N, Story M. A review of environmental influences on food choices. Ann Behav Med. 2009;38(Suppl 1):S56–S73. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Story M, Kaphingst KM, Robinson-O'Brien R, Glanz K. Creating healthy food and eating environments: policy and environmental approaches. Annu Rev Publ Health. 2008;29:253–272. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swinburn B EG, Raza F. Dissecting obesogenic environments: The development and application of a framework for identifying and prioritizing environmental interventions for obesity. Prev Med. 1999;29:563–570. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sorensen G, Linnan L, Hunt MK. Worksite-based research and initiatives to increase fruit and vegetable consumption. Prev Med. 2004;39:S94–S100. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wordell D, Daratha K, Mandal B, Bindler R, Butkus SN. Changes in a middle school food environment affect food behavior and food choices. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012 Jan;112(1):137–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engbers LH van Poppel MNM, Chin A Paw MJM, van Mechelen W. Worksite health promtion programs with environmetnal changes: A systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(1):61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levy DE, Riis J, Sonnenberg LM, Barraclough SJ, Thorndike AN. Food choices of minority and low-income employees: a cafeteria intervention. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(3):240–248. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Kleef E, van Trijp KO, van Trijp HCM. Healthy snacks at the checkout counter: A lab and field study on the impact of shelf arrangement and assortment structure on consumer choices. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1072):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), General Services Administration (GSA), author Health and sustainability guidelines for federal concessions and vending operations. [August 20, 2014]. http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/guidelines/food-service-guidelines.htm. Updated February 2014.

- 25.Kimmons J, Jones S, McPeak HH, Bowden B. Developing and implementing health and sustainability guidelines for institutional food service. Adv Nutr. 2012;3(3):337–342. doi: 10.3945/an.111.001354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), National Institutes of Health, author. Ways to Enhance Children's Activity and Nutrition. We Can! GO, SLOW, and WHOA foods. [August 22, 2014]. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational/wecan/downloads/go-slow-whoa.pdf.

- 27.Iowa Department of Public Health, author. Nutritional Environment Measures Survey-Vending (NEMS-V): Criteria for coding foods. [August 20, 2014]. http://www.nems-v.com/documents/CriteriaforCodingFoods8.8.14.pdf.

- 28.Iowa Department of Public Health, author. Nutrition Environment Measures Survey-Vending (NEMS-V): Criteria for beverages. [August 20, 2014]. http://www.nems-v.com/documents/CriteriaforCodingBeverages8.8.14_002.pdf.

- 29.U.S. Army food service food and beverage criteria. [August 20, 2014]. http://www.quartermaster.army.mil/jccoe/Operations_Directorate/QUAD/nutrition/Program_Criteria_g4g.pdf.

- 30.Iowa Department of Public Health, author. White collar worksite kit. [August 14, 2014]. http://www.nems-v.com/NEMS-VpromoWhiteCollar.html.

- 31.Foster GD, Karpyn A, Wojtanowski AC, et al. Placement and promotion strategies to increase sales of healthier products in supermarkets in low-income, ethnically diverse neighborhoods: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(6):1359–1368. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.075572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]