Abstract

Alterations in embryonic neural stem cells play crucial roles in the pathogenesis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. We hypothesized that embryonic neural stem cells from SOD1G93A individuals might be more susceptible to oxidative injury, resulting in a propensity for neurodegeneration at later stages. In this study, embryonic neural stem cells obtained from human superoxide dismutase 1 mutant (SOD1G93A) and wild-type (SOD1WT) mouse models were exposed to H2O2. We assayed cell viability with mitochondrial succinic dehydrogenase colorimetric reagent, and measured cell apoptosis by flow cytometry. Moreover, we evaluated the expression of the adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) α-subunit, paired box 3 (Pax3) protein, and p53 in western blot analyses. Compared with SOD1WT cells, SOD1G93A embryonic neural stem cells were more likely to undergo H2O2-induced apoptosis. Phosphorylation of AMPKα in SOD1G93A cells was higher than that in SOD1WT cells. Pax3 expression was inversely correlated with the phosphorylation levels of AMPKα. p53 protein levels were also correlated with AMPKα phosphorylation levels. Compound C, an inhibitor of AMPKα, attenuated the effects of H2O2. These results suggest that embryonic neural stem cells from SOD1G93A mice are more susceptible to apoptosis in the presence of oxidative stress compared with those from wild-type controls, and the effects are mainly mediated by Pax3 and p53 in the AMPKα pathway.

Keywords: nerve regeneration, neuroderegeneration, embryonic neural stem cells, adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase α, paired box 3, p53, SOD1G93A mouse, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, oxidative stress, hydrogen peroxide, apoptosis, NSFC grants, neural regeneration

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is a fatal neurodegenerative disease. To date, many related genes and loci have been identified in this disease (Beleza-Meireles and Al-Chalabi, 2009; Maruyama et al., 2010; DeJesus-Hernandez et al., 2011). Mutations in superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) account for 20% of cases of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and 5% of sporadic cases (Rosen, 1993). Several mutations of human SOD1 (SOD1G93A, SOD1G37R, and SOD1G85R) have been investigated in a mouse model (Gurney et al., 1994; Bruijn et al., 1997; Cai and Fan, 2013; Ye et al., 2013). Of these mutant forms, SOD1G93A is the most common. Initial studies detected no significant pathology during the early course of the disease (Gurney et al., 1994). However, several recent reports have shown that pathological and physiological changes occur much earlier than previously thought, even at the embryonic stage. Embryonic alterations in motor neuronal morphology induce hyperexcitability in adult-onset SOD1G93A mice (Martin et al., 2013). Studies on neonatal neuronal circuitry have also shown a hyperexcitable disturbance in SOD1G93A mice (van Zundert et al., 2008). Progressive degeneration of lumbar motor neurons in SOD1G93A transgenic mice has also been suggested to occur at birth (Lowry et al., 2001). In addition to mature neural cells, Luo et al. (2007) recently reported an impairment of SDF1/CXCR4 signaling, which regulates neural development via the promotion of cell survival and proliferation, in neural stem cells (NSCs) derived from SOD1G93A mice. Abnormalities in embryonic NSCs might result in susceptibility to neurodegeneration at a later stage. Thus, identification of early alterations in NSCs might be crucial to understand amyotrophic lateral sclerosis pathogenesis.

Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a central regulator of cellular metabolism. It consists of a catalytic α-subunit and regulatory β- and γ-subunits (Ma et al, 2012). The Thr172 residue of the α-subunit is phosphorylated under specific conditions such as exercise, hypoxia, and oxidative stress (Hardie, 2007). However, the full array of AMPK functions has not yet been elucidated in NSCs, although there have been studies on other neural cell types. For example, AMPK protects embryonic hippocampal neurons from hypoxia-induced cell death and partially guards against oxidative stress-induced cell death in an immortalized cerebellar cell line (Culmsee et al., 2001; Park et al., 2009). Nuclear translocation of AMPK potentiates striatal neurodegeneration (Ju et al., 2011). Furthermore, AMPK regulates forkhead box, class O, mammalian target of rapamycin, and mammalian silent information regulator 2 ortholog (Fulco et al., 2003; Cheng et al., 2004; Greer et al., 2007; Canto et al., 2009), which have been implicated in NSC regulation. Recently, Loken et al. (2012) suggested that AMPK mediates the effects of oxidative stress on neural tube development. It remains to be determined whether AMPK exhibits protective or cell death-inducing effects on NSCs under conditions of oxidative stress.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the effects of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)-induced oxidative stress on embryonic NSCs in the SOD1G93A mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and evaluate whether AMPK has certain effects on NSCs under conditions of oxidative stress.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and culture of NSCs

Fetal mice used in this study were bred under the strain designations B6SJL-Tg(SOD1G93A)1Gur/J and B6SJL-Tg (SOD1)2Gur/J for SOD1G93A transgenic and wild-type SOD1 transgenic mice. They were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Gurney et al., 1994). Brains were removed from the embryos at embryonic day 14 to isolate NSCs, as described previously (Park et al., 2012), with slight modifications. Animal care and experimental protocols were performed in strict accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Animal Care and Ethics Committee at Peking University Third Hospital, China.

Each embryo was genotyped by genomic polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers for the hSOD1 transgene (forward: 5′-CAT CAG CCC TAA TCC ATC TGA-3′; reverse: 5′-CGC GAC TAA CAA TCA AAG TGA-3′). NSCs prepared from SOD1G93A fetal mice (carrying the human SOD1G93A gene) and SOD1WT fetal mice (carrying the human wild-type SOD1 gene) were used for experiments. SOD1WT NSCs served as controls. After the meninges were removed, single cell suspensions were obtained by mechanical dissociation. Then, the cell suspensions were centrifuged at 100 × g for 5 minutes. After discarding the supernatant, the cells were re-suspended with 1 mL complete neurosphere medium. The cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 105/mL in 10 mL complete NSC medium. NSCs were cultured in maintenance medium containing Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium/Ham's F-12 medium (DMEM/F12) supplemented with serum-free neurobasal growth supplement 2% v/v (B27, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), recombinant human basic fibroblast growth factor (20 ng/mL, PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA), and recombinant human epidermal growth factor (20 ng/mL, PeproTech) in a humidified incubator (37°C, 5% CO2). Neurospheres with diameters of about 200 μm were sub-cultured after 3–5 days.

Test groups

After genotyping, SOD1G93A NSCs and SOD1WT NSCs were exposed to 0.5 mmol/L H2O2, 1 mmol/L H2O2, or normal conditions. To elucidate the role of AMPK in H2O2-induced apoptosis of NSCs, we employed an AMPK activator (5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxyamide ribonucleoside, AICAR) or inhibitor (compound C). The NSCs were divided into four groups: normal, H2O2, AICAR (positive control), and H2O2 plus compound C. The 3% (w/w) H2O2 solution, AICAR, and compound C were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA).

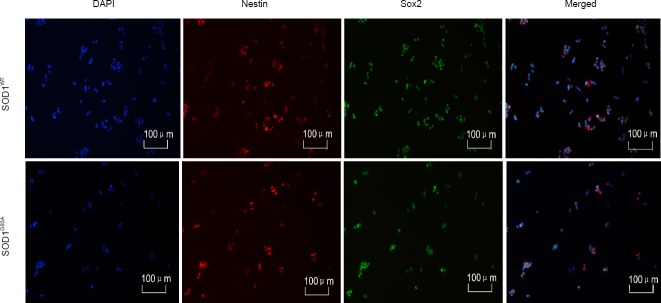

Immunocytochemistry

NSCs (4 × 105/mL) were cultured on coverslips coated with poly-L-ornithine (Sigma-Aldrich) for 36 hours. The cells were then incubated with the following primary antibodies at 4°C overnight for double immunolabeling: mouse anti-Nestin monoclonal antibody (1:100; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and rabbit anti-Sox2 monoclonal antibody (1:100; Epitomics, Burlingame, CA, USA). Then, the cells were incubated with anti-rabbit IgG (1:100) and anti-mouse IgG (1:100) secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor® 488 or 594 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at room temperature for 1 hour. Lastly, the cells were mounted in mounting medium containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Fluorescence images were captured using an upright fluorescence microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Hesse-Darmstadt, Germany). Controls for negative staining were prepared with PBS in place of the primary antibodies.

Cell viability and proliferation assays

NSCs were seeded onto poly-L-ornithine-coated 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104/mL for 36 hours, and then cultured under the four conditions listed above. Then, the culture medium was removed and replaced with normal medium. A total of 10 μL mitochondrial succinic dehydrogenase colorimetric reagent (Cell Counting Kit-8 reagent, Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan) was added to each well according to the manufacturer's protocol, followed by incubation for 3 hours at 37°C with 5% CO2. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm on a microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) at a reference wavelength of 600 nm.

Flow cytometric analysis

Fluorescein isothiocyanate and propidium iodide (FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit, BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) were used to assess NSC apoptosis. Intact cells were Annexin V(–)/PI(–). Early and late apoptotic cells were Annexin V(+)/PI(–) and Annexin V(+)/PI(+), respectively. Necrotic cells were Annexin V(–)/PI(+).

Western blot analysis

NSCs were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer (Apply Technologies, Beijing, China) in the presence of protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich) on ice according to the manufacturer's instructions. The protein concentration was measured with a BCA™ Protein Assay Kit (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL, USA). Samples containing 30 μg protein were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose filter membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The membranes were incubated at 4°C overnight with the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti-AMPKα (1:1,000), rabbit anti-phospho-AMPKα (1:1,000), mouse anti-p53 (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA, USA), and goat anti-paired box 3 (Pax3, 1:250; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). A mouse anti-β-actin antibody (1:1,000; Earthox, San Francisco, CA, USA) was used to label β-actin for normalization. The gray value of protein bands was detected using an infrared imaging system (Odyssey, LICOR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA).

RNA preparation and real-time PCR

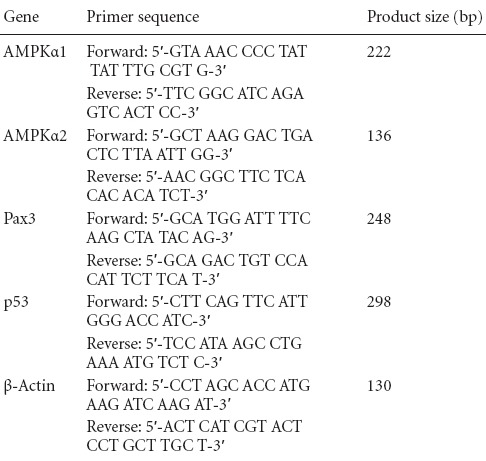

Total RNA from NSCs was isolated using a single-step RNA extraction reagent (Trizol, Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg total RNA using avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (Reverse Transcription System, Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and amplified by PCR (GoTaq® qPCR Master Mix, Promega). The PCR conditions were as follows: 95°C for 2 minutes and then 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 58°C for 30 seconds. The primer sequences are listed in Table 1. The expression level of the target gene was normalized to mouse β-actin, and the relative gene expression (2-ΔΔCt) was calculated using the previous method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

Table 1.

Primer sequence and product size of real-time PCR analyses

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 19.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) using one-way analysis of variance followed by the least significant difference post-hoc test. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

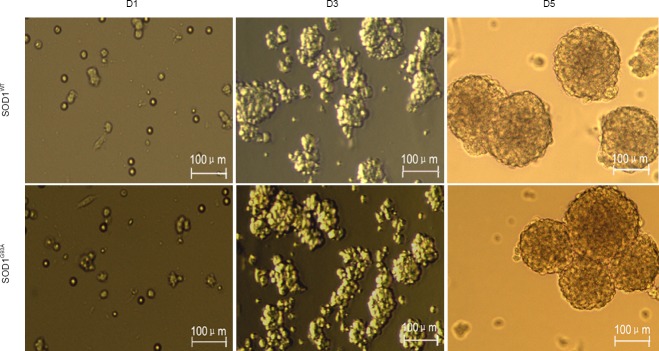

Culture and identification of mouse embryonic NSCs

SOD1G93A and SOD1WT NSCs were isolated from fetal brains, expanded as neurospheres, and passaged every 3–5 days (Figure 1). There was no substantial difference in the formation of neurospheres between the two types of NSCs. In immunofluorescence analyses, most of the cells were positive for the intermediate filament protein Nestin and the transcription factor Sox2 (Figure 2), which are markers of NSCs.

Figure 1.

Morphology of neural stem cells prepared from embryos of SOD1WT and SOD1G93A mice at 1, 3, and 5 days after culture (D1, 3, and 5) (inverted microscope).

Embryonic neural stem cells formed typical neurospheres after in vitro culture. SOD1: Superoxide dismutase 1.

Figure 2.

Identification of neural stem cells by double immunofluorescence staining of Nestin (red) and Sox2 (green) (immunocytochemistry, fluorescence microscope).

Nestin and Sox2 were expressed in the neural stem cells derived from mouse embryos. Blue: DAPI-labeled nuclei. SOD1: Superoxide dismutase 1.

Effect of H2O2-induced oxidative stress on the apoptosis of NSCs from SOD1G93A mice

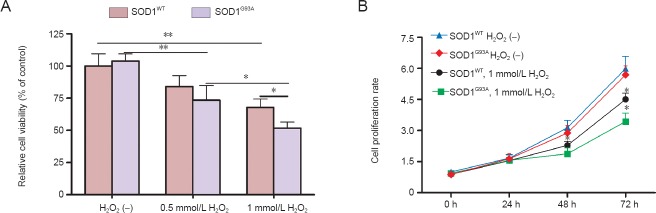

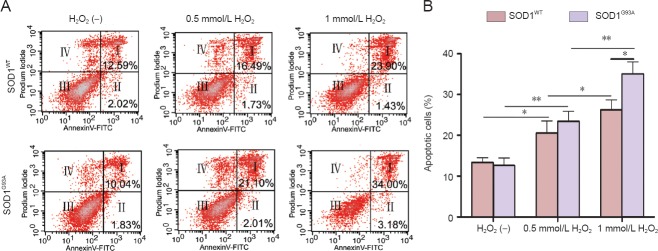

To evaluate differences in the susceptibilities of SOD1G93A and SOD1WT NSCs to oxidative stress, the NSCs were exposed to H2O2 (0.5 and 1 mmol/L) for 12 hours. As expected, the viability of the NSCs was significantly decreased by H2O2 treatment in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3A, P = 0.004, P = 0.016). Importantly, the viability of SOD1G93A NSCs was significantly more decreased than that of SOD1WT cells when treated with 1 mmol/L H2O2 (P = 0.026). To further investigate the effects of H2O2 on NSC proliferation, cell viability was examined at several time points (0, 24, 48, and 72 hours). In untreated controls, no significant difference was observed in the proliferation of SOD1G93A and SOD1WT cells (Figure 3B). However, when 1 mmol/L H2O2 was added at 24 hours, cell proliferation was inhibited to 72 hours, and the viability of SOD1G93A NSCs at 72 hours was significantly lower than that of the SOD1WT NSCs. To evaluate the degree of injury induced by H2O2 in NSCs, apoptosis was assessed by Annexin V-FITC and PI staining using flow cytometry (Figure 4A). Consistent with the observations in the cell viability assay, apoptosis was significantly enhanced by H2O2 treatment. When SOD1WT and SOD1G93A NSCs were not treated with H2O2, the percentages of apoptotic cells were 13.31 ± 1.21% and 12.57 ± 1.87%, respectively. When SOD1WT and SOD1G93A NSCs were treated with 0.5 mmol/L H2O2, the percentages of apoptotic cells increased from 13.31 ± 1.21% and 12.57 ± 1.87% to 20.52 ± 3.04% and 23.43 ± 2.45% (P = 0.01 and P = 0.002), respectively. When SOD1WT and SOD1G93A NSCs were treated with 1 mmol/L H2O2, the percentage of apoptotic cells increased from 13.31% ± 1.21% and 12.57 ± 1.87% to 26.22 ± 2.47% and 35.06 ± 2.95% (P = 0.026 and P = 0.001), respectively (Figure 4B). In the 1 mmol/L H2O2 group, the percentage of apoptotic SOD1G93A NSCs was significantly higher than that of SOD1WT cells (P = 0.029). These results suggest that SOD1G93A NSCs are more susceptible to oxidative stress induced by H2O2.

Figure 3.

Neural stem cells (NSCs) in SOD1G93A mice are more susceptible to oxidative injury induced by H2O2 (cell viability and proliferation assays).

(A) Effects of H2O2 on the cell viability of NSCs. The absorbance value of untreated SOD1WT NSCs was set as 100%. (B) Effect of H2O2 on the pro-liferation of NSCs. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Data are presented as the mean ± SD and analyzed using one-way analysis of variance followed by the least significant difference post-hoc test. Each set of measurements was performed in triplicate in at least five independent experiments. H2O2 (–) indicates no treatment; h: hour(s); SOD1: superoxied dismutase 1.

Figure 4.

Neural stem cells (NSCs) in SOD1G93A mice are more susceptible to apoptosis induced by H2O2 (flow cytometry).

(A) Representative scatter plots showing apoptosis in H2O2-treated NSCs by Annexin V-FITC and PI staining and flow cytometry. (I) Late apoptotic cells; (II) early apoptotic cells; (III) intact cells; (IV) necrotic cells. (B) Quantification of apoptotic cells. NSCs were cultured for 36 hours and then treated with H2O2 for 12 hours, followed by apoptosis detection. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. The values are the mean ± SD of five independent experiments (one-way analysis of variance followed by the least significant difference post-hoc test). H2O2 (–) indicates no treatment. SOD1: Superoxide dismutase 1.

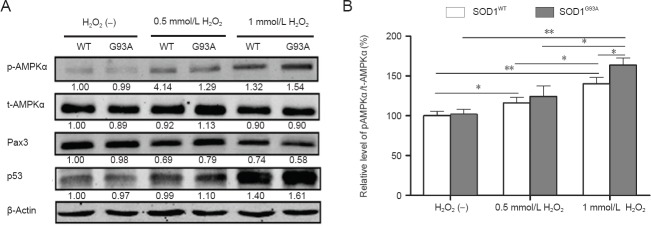

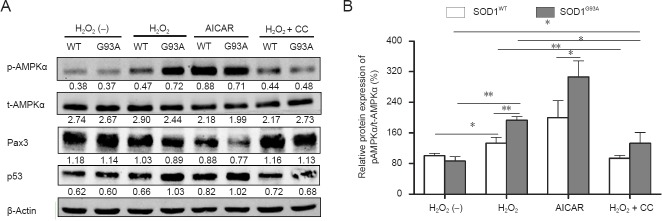

AMPK phosphorylation was enhanced in H2O2-treated SOD1G93A NSCs together with changes in Pax3 and p53 levels

To address the potential role of AMPK in the apoptosis of SOD1G93A and SOD1WT NSCs, we evaluated phosphorylation of AMPKα (Figure 5A). Cells were cultured for 36 hours followed by H2O2 treatment. Significant increases in the phosphorylation of AMPKα occurred after 12 hours of H2O2 exposure, which was markedly higher in SOD1G93A NSCs than that in SOD1WT cells in the 1 mmol/L H2O2 group (Figure 5B; P = 0.019). AMPK has been also shown to inhibit Pax3 expression in a mouse model of diabetic embryopathy (Wu et al., 2012). To confirm our hypothesis that Pax3 expression is also regulated by AMPK in this model, we examined Pax3 protein levels (Figure 5A). As a result, we found that Pax3 protein levels were clearly decreased in NSCs exposed to H2O2, and these changes were more obvious in SOD1G93A NSCs treated with 1 mmol/L H2O2. A loss of Pax3 expression has been shown to increase p53 protein levels and apoptosis, resulting in neural tube defects (Chappell et al., 2009). When we examined p53 protein levels (Figure 5A), we found an inverse correlation in the concentrations of p53 and Pax3 proteins, i.e., downregulation of Pax3 protein levels enhanced the levels of p53 protein. The above data indicated that the AMPK pathway might be involved in the apoptosis of NSCs induced by H2O2.

Figure 5.

Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) phosphorylation levels are increased in SOD1G93A neural stem cells (NSCs) by H2O2 exposure with corresponding changes in Pax3 and p53 levels (western blot analysis).

(A) Representative western blots displaying expression or activation of AMPK α-subunit (AMPKα), paired box 3 (Pax3), and p53 in NSCs treated with or without H2O2. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Data below each lane represent the relative gray scale compared with β-actin control bands. Values below SOD1WT NSCs treated without H2O2 were set as 1. (B) Phosphorylation levels of AMPKα were quantified relative to the total AMPKα level. The expression level in untreated SOD1WT NSCs was set at 100%. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Data are presented as the mean ± SD and analyzed using one-way analysis of variance followed by the least significant difference post-hoc test. (–): Untreated; WT: superoxide dismutase 1 wild-type neural stem cells; G93A: SOD1G93A neural stem cells; p-AMPKα: phosphorylated AMPKα; t-AMPKα: total AMPKα. SOD1: Superoxide dismutase 1.

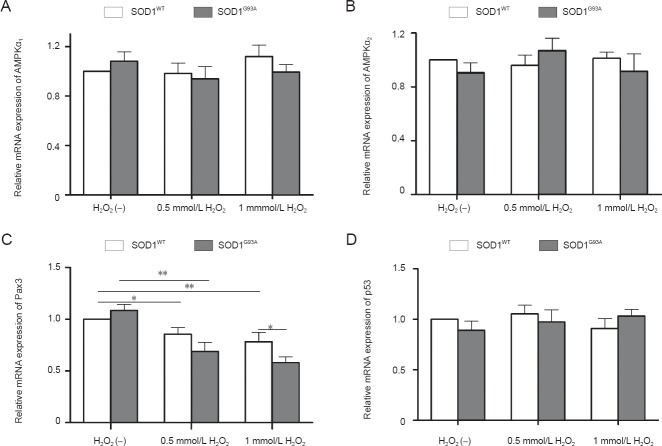

In addition, we found that the mRNA levels of AMPKα1, AMPKα2, and p53 were unaffected by H2O2 treatment (Figure 6A, B, and D). The downregulation of Pax3 mRNA by H2O2 treatment was statistically significant, and Pax3 mRNA was significantly lower in SOD1G93A NSCs compared with that in SOD1WT NSCs in the 1 mmol/L H2O2 group (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of the mRNA expression of adenosine monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase α1 subunit (AMPKα1) (A), AMP-activated protein kinase α2 subunit (AMPKα2) (B), paired box 3 (Pax3) (C), and p53 (D) in neural stem cells under different treatment conditions.

H2O2 (–): Untreated. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Data are presented as the mean ± SD and analyzed using one-way analysis of variance followed by the least significant difference post-hoc test. SOD1: Superoxide dismutase 1.

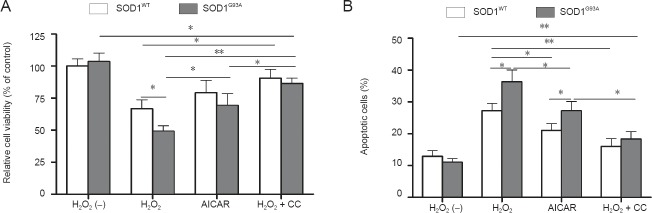

Inhibition of AMPK activity cancelled the effects of H2O2 on the apoptosis of NSCs

To further confirm the role of AMPK in H2O2-induced apoptosis of NSCs, we employed an AMPK activator (AICAR, 1 mmol/L) and inhibitor (compound C, 1 μmol/L). Cells were maintained in growth medium for 36 hours prior to treatment with different agents. Based on our previous results, 1 mmol/L H2O2 was used in these experiments. Compared with controls, NSCs treated with AICAR for 12 hours in the absence of H2O2 demonstrated a decrease in viability, although this effect was not significant compared with that in H2O2-treated cells (Figure 7A; P = 0.009 and P = 0.001). When NSCs were preincubated for 1 hour with compound C followed by H2O2 treatment for 12 hours, cell viability was slightly but significantly reversed compared with that in the 1 mmol/L H2O2 group. The cell viability of SOD1G93A NSCs was also similar to SOD1WT cells when treated with 1 mmol/L H2O2 plus compound C (Figure 7A; P = 0.431). Similar results were obtained in cell apoptosis assays (Figure 7B). Next, we investigated the effect of AICAR and compound C on the phosphorylation of AMPKα and protein levels of Pax3 and p53 in NSCs using western blot analyses (Figure 8A). Similar to H2O2 treatment, phosphorylation of AMPKα was increased in response to AICAR. In contrast, compound C inhibited H2O2-induced AMPKα phosphorylation. There was no significant difference in AMPKα phosphorylation of SOD1G93A and SOD1WT NSCs when treated with 1 mmol/L H2O2 plus compound C (Figure 8B). Pax3 expression was inversely correlated with the changes in AMPKα phosphorylation of H2O2- and AICAR-treated NSCs with AICAR treatment producing the most pronounced decrease in Pax3 levels. Pax3 expression was partially restored by compound C in H2O2-treated NSCs (Figure 8A). Moreover, p53 protein levels were enhanced by AICAR, whereas the effects of H2O2 on p53 were partially blocked by compound C. In summary, inhibition of AMPK activity attenuated the effect of H2O2 on NSCs. The above data indicate that AMPK activation triggers p53-dependent apoptosis of NSCs induced by H2O2.

Figure 7.

Effects of adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activator 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxyamide ribonucleoside (AICAR) and inhibitor compound (CC) on the viability and apoptosis of neural stem cells (NSCs).

(A) Cell viability was significantly affected by the addition of AICAR or compound C. The absorbance value of untreated superoxide dismutase 1 wild-type (SOD1WT) NSCs was set at 100%. (B) Quantitative assessment of NSC apoptosis by AnnexinV-FITC and PI staining and flow cytometry under different treatment conditions. H2O2 (–): Untreated. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Data are presented as the mean ± SD and analyzed using one-way analysis of variance followed by the least significant difference post-hoc test. FITC: Fluoresscen isothiocyante; PI: propidium iodide.

Figure 8.

Effects of adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activator 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxyamide ribonucleoside (AICAR) and inhibitor compound (CC) on the phosphorylation of AMPKα and protein levels of Pax3 and p53 in neural stem cells (NSCs) (western blot analysis).

(A) Representative western blots displaying the phosphorylation of AMPKα, paired box 3 (Pax3), and p53 protein in NSCs exposed to different fac-tors. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Data below each lane represent the relative gray scale compared with β-actin control bands. (B) Phos-phorylation levels of AMPKα relative to total AMPKα levels. The expression level in untreated superoxide dismutase 1 wild-type (SOD1WT) NSCs was set at 100%. Data are presented as the mean ± SD and analyzed using one-way analysis of variance followed by the least significant difference post-hoc test. p-AMPKα: Phosphorylated AMPKα; t-AMPKα: total AMPKα; H2O2 (–): Untreated; WT: SOD1WT NSCs; G93A: SOD1G93A NSCs *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; SOD1: Superoxide dismutase 1.

Discussion

The mechanism underlying mutant SOD1 toxicity has not yet been elucidated. Although some mutants of SOD1 (such as A4V and G85R) exhibit reduced dismutase activity, other mutants (such as G37R and G93A) retain full dismutase activity (Yim et al., 1996). Because SOD1G93A displays full dismutase activity, the mutation itself may not result in apoptosis, which is consistent with the observation that the cell viability of SOD1G93A and SOD1WT NSCs is similar under normal conditions. However, the SOD1 mutation might make cells more vulnerable to oxidative stress. For example, Rogers and Schor (2010) indicated that proteins involved in neurodegenerative disease often play critical roles in early development of the central nervous system. SOD1 contributes to the organogenesis of embryos, including neurogenesis (Kase et al., 2012). Therefore, it is unclear why the disease appears later in life. Smith proposed a “two-hit” hypothesis for neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Zhu et al., 2004, 2007). The first “hit” is usually a genetic factor, which presents a vulnerability, and the second “hit” is an environmental factor that triggers the neurodegenerative process. This hypothesis is consistent with our observation that, compared with SOD1WT NSCs, more SOD1G93A NSCs were apoptotic when treated with 1 mmol/L H2O2. This finding demonstrated that expression of the SOD1G93A gene increased the vulnerability of NSCs to oxidative stress. The “two-hit” hypothesis may also explain why Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis are age-related diseases. Reactive oxygen species gradually increase with age. When reactive oxygen species increase to a specific threshold, neuronal degeneration may be triggered in some individuals with the mutant gene.

Li et al. (2012) examined rat neural progenitor cells and found that SOD1G93A overexpression increases the cellular sensitivity to oxidative stress. However, elucidation of the pathway underlying SOD1G93A susceptibility has not been studied. In the present study, significant increases in the phosphorylation of AMPKα and relevant changes in Pax3 and p53 levels occurred in the presence of H2O2, indicating involvement of the AMPK/Pax3/p53 signaling pathway in the H2O2-induced apoptosis of NSCs. Interestingly, phosphorylation of AMPKα and subsequent changes in Pax3 and p53 levels were markedly greater in SOD1G93A NSCs compared with those in SOD1WT cells in the 1 mmol/L H2O2 group. These data suggest that activation of the AMPK pathway likely leads to excessive apoptosis of SOD1G93A NSCs. Further experiments using the AMPK activator and inhibitor also clearly indicated that activation of the AMPK/Pax3/p53 pathway mediated the susceptibility of SOD1G93A mutant cells to oxidative stress. However, the AMPK activator and inhibitor had partial effects with regard to H2O2 alone, which implies the involment of other cell death signaling pathways such as caspases.

Activated AMPK can also undergo nuclear translocation and regulate gene expression by phosphorylating nuclear proteins (Ju et al., 2011). Based on the data in Figures 5 and 6, AMPK inhibited Pax3 transcription, but the underlying mechanism requires further study. In addition, the protein levels of p53 were inversely correlated with those of Pax3, although the mRNA levels of p53 showed no significant change upon downregulation of Pax3 mRNA. These results were consistent with a previous study demonstrating that Pax3 induces p53 ubiquitination and degradation independent of transcription (Wang et al., 2011). Thus, Pax3 is required to block p53-dependent apoptosis and suppression of Pax3 facilitates p53-dependent apoptosis.

Many recent studies have focused on bioenergetic abnormalities in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Both amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients and two commonly used mutant SOD1 mice (G86R and G93A mice) display increased resting energy expenditure, a hypermetabolic phenotype, and compromised mitochondrial function (Dupuis et al., 2004, 2011; Bouteloup et al., 2009; Funalot et al., 2009; Chiang et al., 2010). These metabolic abnormalities have been associated with activation of the energy sensor AMPK. The activity of AMPK is increased in the spinal cords of mutant SOD1 mice, and reducing AMPK activity either pharmacologically or genetically prevents mutant SOD1-induced motor neuron death in vitro (Lim et al., 2012). In this study, we investigated the correlation of AMPK with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. We found that AMPK activation promoted the apoptosis of embryonic NSCs induced by oxidative stress in SOD1G93A mice. In addition to embryonic NSCs, we should draw attention to adult and transplanted NSCs. The pathological processes of motor neuron degeneration stimulats NSC proliferation and neurogenesis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients and adult SOD1G93A mice (Chi et al., 2006; Guan et al., 2007; Galan et al., 2011). Human NSCs are emerging as a promising cellular therapy for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Implanted NSCs secrete high levels of the trophic factors that protect spared motor neurons, integrate into the parenchyma, and may differentiate into neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes (Hefferan et al., 2012; Teng et al., 2012). However, the survival of transplanted NSCs over time is a challenge because of the altered niche in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Liu and Martin, 2006). Therefore, it is important to assess whether AMPK regulates adult NSC proliferation and the survival of implanted NSCs.

In conclusion, our data indicate that activation of the AMPK/Pax3/p53 pathway promotes the apoptosis of SOD1G93A NSCs induced by oxidative stress. Thus, AMPK/Pax3/p53 might represent a novel target for protecting SOD1G93A NSCs from oxidative injury, which might also contribute to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis therapy.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the staff from Clinical Stem Cell Research Center, Peking University Third Hospital, China for their excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China, No. 81030019.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Copyedited by Cone L, Norman C, Wang J, Yang Y, Li CH, Song LP, Zhao M

References

- Beleza-Meireles A, Al-Chalabi A. Genetic studies of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: controversies and perspectives. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2009;10:1–14. doi: 10.1080/17482960802585469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouteloup C, Desport JC, Clavelou P, Guy N, Derumeaux-Burel H, Ferrier A, Couratier P. Hypermetabolism in ALS patients: an early and persistent phenomenon. J Neurol. 2009;256:1236–1242. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5100-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruijn LI, Becher MW, Lee MK, Anderson KL, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Sisodia SS, Rothstein JD, Borchelt DR, Price DL, Cleveland DW. ALS-linked SOD1 mutant G85R mediates damage to astrocytes and promotes rapidly progressive disease with SOD1-containing inclusions. Neuron. 1997;18:327–338. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80272-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai B, Fan DS. Germline degradation of a mouse model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis when breeding. Zhongguo Zuzhi Gongcheng Yanjiu. 2013;17:4521–4528. [Google Scholar]

- Canto C, Gerhart-Hines Z, Feige JN, Lagouge M, Noriega L, Milne JC, Elliott PJ, Puigserver P, Auwerx J. AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD+ metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature. 2009;458:1056–1060. doi: 10.1038/nature07813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell JH, Jr, Wang XD, Loeken MR. Diabetes and apoptosis: neural crest cells and neural tube. Apoptosis. 2009;14:1472–1483. doi: 10.1007/s10495-009-0338-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng SW, Fryer LG, Carling D, Shepherd PR. Thr2446 is a novel mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) phosphorylation site regulated by nutrient status. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:15719–15722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300534200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi L, Ke Y, Luo C, Li B, Gozal D, Kalyanaraman B, Liu R. Motor neuron degeneration promotes neural progenitor cell proliferation, migration, and neurogenesis in the spinal cords of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mice. Stem Cells. 2006;24:34–43. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang PM, Ling J, Jeong YH, Price DL, Aja SM, Wong PC. Deletion of TDP-43 down-regulates Tbc1d1, a gene linked to obesity, and alters body fat metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:16320–16324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002176107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culmsee C, Monnig J, Kemp BE, Mattson MP. AMP-activated protein kinase is highly expressed in neurons in the developing rat brain and promotes neuronal survival following glucose deprivation. J Mol Neurosci. 2001;17:45–58. doi: 10.1385/JMN:17:1:45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJesus-Hernandez M, Mackenzie IR, Boeve BF, Boxer AL, Baker M, Rutherford NJ, Nicholson AM, Finch NA, Flynn H, Adamson J, Kouri N, Wojtas A, Sengdy P, Hsiung GY, Karydas A, Seeley WW, Josephs KA, Coppola G, Geschwind DH, Wszolek ZK. Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron. 2011;72:245–256. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis L, Oudart H, Rene F, Gonzalez de Aguilar JL, Loeffler JP. Evidence for defective energy homeostasis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: benefit of a high-energy diet in a transgenic mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11159–11164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402026101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis L, Pradat PF, Ludolph AC, Loeffler JP. Energy metabolism in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:75–82. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70224-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulco M, Schiltz RL, Iezzi S, King MT, Zhao P, Kashiwaya Y, Hoffman E, Veech RL, Sartorelli V. Sir2 regulates skeletal muscle differentiation as a potential sensor of the redox state. Mol Cell. 2003;12:51–62. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00226-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funalot B, Desport JC, Sturtz F, Camu W, Couratier P. High metabolic level in patients with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2009;10:113–117. doi: 10.1080/17482960802295192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galan L, Gomez-Pinedo U, Vela-Souto A, Guerrero-Sola A, Barcia JA, Gutierrez AR, Martinez-Martinez A, Jimenez MS, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Matias-Guiu J. Subventricular zone in motor neuron disease with frontotemporal dementia. Neurosci Lett. 2011;499:9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer EL, Oskoui PR, Banko MR, Maniar JM, Gygi MP, Gygi SP, Brunet A. The energy sensor AMP-activated protein kinase directly regulates the mammalian FOXO3 transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:30107–30119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705325200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan YJ, Wang X, Wang HY, Kawagishi K, Ryu H, Huo CF, Shimony EM, Kristal BS, Kuhn HG, Friedlander RM. Increased stem cell proliferation in the spinal cord of adult amyotrophic lateral sclerosis transgenic mice. J Neurochem. 2007;102:1125–1138. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurney ME, Pu H, Chiu AY, Dal Canto MC, Polchow CY, Alexander DD, Caliendo J, Hentati A, Kwon YW, Deng HX. Motor neuron degeneration in mice that express a human Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase mutation. Science. 1994;264:1772–1775. doi: 10.1126/science.8209258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie DG. AMP-activated/SNF1 protein kinases: conserved guardians of cellular energy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:774–785. doi: 10.1038/nrm2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefferan MP, Galik J, Kakinohana O, Sekerkova G, Santucci C, Marsala S, Navarro R, Hruska-Plochan M, Johe K, Feldman E, Cleveland DW, Marsala M. Human neural stem cell replacement therapy for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis by spinal transplantation. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42614. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju TC, Chen HM, Lin JT, Chang CP, Chang WC, Kang JJ, Sun CP, Tao MH, Tu PH, Chang C, Dickson DW, Chern Y. Nuclear translocation of AMPK-alpha1 potentiates striatal neurodegeneration in Huntington's disease. J Cell Biol. 2011;194:209–227. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201105010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kase BA, Northrup H, Morrison AC, Davidson CM, Goiffon AM, Fletcher JM, Ostermaier KK, Tyerman GH, Au KS. Association of copper-zinc superoxide dismutase (SOD1) and manganese superoxide dismutase (SOD2) genes with nonsyndromic myelomeningocele. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2012;94:762–769. doi: 10.1002/bdra.23065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Strykowski R, Meyer M, Mulcrone P, Krakora D, Suzuki M. Male-specific differences in proliferation, neurogenesis, and sensitivity to oxidative stress in neural progenitor cells derived from a rat model of ALS. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48581. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim MA, Selak MA, Xiang Z, Krainc D, Neve RL, Kraemer BC, Watts JL, Kalb RG. Reduced activity of AMP-activated protein kinase protects against genetic models of motor neuron disease. J Neurosci. 2012;32:1123–1141. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6554-10.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Martin LJ. The adult neural stem and progenitor cell niche is altered in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mouse brain. J Comp Neurol. 2006;497:468–488. doi: 10.1002/cne.21012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry KS, Murray SS, McLean CA, Talman P, Mathers S, Lopes EC, Cheema SS. A potential role for the p75 low-affinity neurotrophin receptor in spinal motor neuron degeneration in murine and human amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2001;2:127–134. doi: 10.1080/146608201753275463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Xue H, Pardo AC, Mattson MP, Rao MS, Maragakis NJ. Impaired SDF1/CXCR4 signaling in glial progenitors derived from SOD1(G93A) mice. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:2422–2432. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma YC, Zhu R, Li JP. Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase and myofibrillar protein degradation. Zhongguo Zuzhi Gongcheng Yanjiu. 2012;16:341–344. [Google Scholar]

- Martin E, Cazenave W, Cattaert D, Branchereau P. Embryonic alteration of motoneuronal morphology induces hyperexcitability in the mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;54:116–126. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama H, Morino H, Ito H, Izumi Y, Kato H, Watanabe Y, Kinoshita Y, Kamada M, Nodera H, Suzuki H. Mutations of optineurin in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature. 2010;465:223–226. doi: 10.1038/nature08971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HR, Kong KH, Yu BP, Mattson MP, Lee J. Resveratrol inhibits the proliferation of neural progenitor cells and hippocampal neurogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:42588–42600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.406413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M, Song KS, Kim HK, Park YJ, Kim HS, Bae MI, Lee J. 2-Deoxy-d-glucose protects neural progenitor cells against oxidative stress through the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. Neurosci Lett. 2009;449:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers D, Schor NF. The child is father to the man: developmental roles for proteins of importance for neurodegenerative disease. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:151–158. doi: 10.1002/ana.21841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen DR. Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature. 1993;364:362. doi: 10.1038/364362c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng YD, Benn SC, Kalkanis SN, Shefner JM, Onario RC, Cheng B, Lachyankar MB, Marconi M, Li J, Yu D, Han I, Maragakis NJ, Llado J, Erkmen K, Redmond DE, Jr, Sidman RL, Przedborski S, Rothstein JD, Brown RH, Jr, Snyder EY. Multimodal actions of neural stem cells in a mouse model of ALS: a meta-analysis. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:165ra164. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Zundert B, Peuscher MH, Hynynen M, Chen A, Neve RL, Brown RH, Jr, Constantine-Paton M, Bellingham MC. Neonatal neuronal circuitry shows hyperexcitable disturbance in a mouse model of the adult-onset neurodegenerative disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurosci. 2008;28:10864–10874. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1340-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XD, Morgan SC, Loeken MR. Pax3 stimulates p53 ubiquitination and degradation independent of transcription. PLoS One. 2011;6:e29379. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Viana M, Thirumangalathu S, Loeken MR. AMP-activated protein kinase mediates effects of oxidative stress on embryo gene expression in a mouse model of diabetic embryopathy. Diabetologia. 2012;55:245–254. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2326-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye X, Ma CC, Yao Y, Zang DW. Synapsin expression of endogenous neural stem cell membrane in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Zhongguo Zuzhi Gongcheng Yanjiu. 2013;17:3527–3532. [Google Scholar]

- Yim MB, Kang JH, Yim HS, Kwak HS, Chock PB, Stadtman ER. A gain-of-function of an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated Cu, Zn-superoxide dismutase mutant: An enhancement of free radical formation due to a decrease in Km for hydrogen peroxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:5709–5714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Raina AK, Perry G, Smith MA. Alzheimer's disease: the two-hit hypothesis. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:219–226. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00707-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Lee HG, Perry G, Smith MA. Alzheimer disease, the two-hit hypothesis: an update. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1772:494–502. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]