ABSTRACT

Momentum is building to replace the current fee-for-service payment system with value-based reimbursement models that aim to deliver high quality care at lower costs. Although the goals of payment and delivery system reforms to improve quality and reduce costs are clear, the actual path by which provider groups can achieve these goals is not well understood, in large part because the role of identifying and discouraging the use of low-value, high-cost services and encouraging the use of high-value, low-cost services has traditionally fallen to health plans, not provider groups. The shifting focus towards provider accountability for costs and quality promises to expand the role of provider organizations from mainly delivering care to both delivering and prioritizing it based on costs and quality. We discuss how progress on two important but challenging fronts will be needed for provider groups to successfully translate evidence into value. First, robust evidence on the costs and benefits of treatments will need to be developed and made easily accessible to provider groups. Second, provider groups will need to translate that evidence into systems that support cost-effective clinical decisions.

KEY WORDS: health care reform, health care quality, cost effectiveness

Momentum is building to replace the current fee-for-service payment system with value-based reimbursement models that aim to deliver high quality care at lower costs. At the heart of this change are provider organizations that are increasingly being tasked with both recognizing and implementing health care practices that improve outcomes and reduce costs. Several payment and delivery system initiatives foster or rely on this role of provider groups, including accountable care organizations, bundled payment programs, and patient-centered medical homes. These initiatives have been bolstered by recent campaigns to educate physicians about commonly overused tests, treatments, and services.1,2

Although the goals of improving quality and reducing costs are clear, the actual path by which provider groups can achieve these goals is not well understood, in large part because the role of identifying and discouraging the use of low-value, high-cost services and encouraging the use of high-value, low-cost services has traditionally fallen to health plans, not provider groups. For example, through utilization reviews, prior authorizations, selective benefit designs (e.g., tiered pricing), and similar interventions, health plans have played a major role in the stewardship of health care resources that are high cost but offer little clinical benefit. Similarly, while plans have generally focused more on discouraging use of high-cost, low value services, they are playing an increasingly larger role in identifying and encouraging services that are low-cost and high value (e.g., through value-based insurance designs). In contrast, in the setting of generous insurance coverage and a largely fee-for-service reimbursement system, provider groups have been less engaged in making direct calculations of cost and benefit when making individual treatment decisions.

The shifting focus towards provider accountability for costs and quality promises to expand the role of provider organizations from mainly delivering care to both delivering and prioritizing it based on costs and quality. Progress on two important but challenging fronts will be needed for provider groups to successfully translate evidence into value. First, robust evidence on the costs and benefits of treatments will need to be developed and made easily accessible to provider groups. Second, provider groups will need to translate that evidence into systems that support cost-effective clinical decisions.

BUILDING ACTIONABLE EVIDENCE ON LOW-VALUE AND HIGH-VALUE SERVICES

Delivering care based on its benefits and costs will first require the identification and dissemination of actionable evidence to provider organizations—i.e., robust evidence on high-cost, low-value services that providers can safely reduce, as well as evidence on low-cost, high-value services that providers should unequivocally encourage.

A number of resources have increasingly become available to help provider groups easily identify high-cost, low-value health care services that are over-utilized. For example, on the basis of recommendations by specific physician specialty societies, the Choosing Wisely campaign has published evidence-based lists of services that are over-utilized and can safely reduce costs if not provided to patients (e.g., preoperative cardiac stress testing in patients undergoing low-risk non-cardiac surgery, routine echocardiography in patients with asymptomatic and mild native cardiac valve disease, and routine postoperative deep vein thrombosis ultrasonography screening after elective hip or knee arthroplasty). Similar ‘low-value’ lists have been produced by a variety of organizations,3 including health management firms engaged in clinical analytics of commonly utilized, costly services.

Substantial evidence also exists for a number of low-cost, high-value services that have traditionally been reimbursed, for example, annual eye exams for patients with diabetes and preventive service visits for patients with multiple chronic illnesses. In contrast to such process measures of quality, however, other low-cost, high-value services also exist that have typically not been reimbursed, but for which evidence exists to support their value. The benefits of a campaign akin to Choosing Wisely that identifies historically unreimbursed low-cost, high-value services could be substantial.

Consider, for example, that physician office visits have typically been reimbursed by payers, while other forms of patient care such as physician phone calls, emails, and video consultations have not. Virtual video consultations between patients and specialists have been demonstrated to produce more timely information for referring physicians and high levels of patient satisfaction without the need for specialty office visits, yet have not been reimbursed.4

The result of this reimbursement incentive has been clear—office visits have been favored over other less costly, but equally quality-improving approaches to delivering care.5 Similarly, early mobilization of intensive care unit patients through physical therapy and nurse engagement has been associated with reduced hospital length of stay, costs, and rates of nosocomial illnesses, yet early mobility programs are infrequently utilized, despite being low cost and highly cost saving.6 Finally, oral nutritional supplements for hospitalized patients have been associated with reductions in hospital length of stay, readmission rates and costs, and yet utilization has been low, partly because hospitals and provider groups have typically not been incentivized to provide these services.7 Although these services represent opportunities to improve quality and lower cost, they have been adopted slowly under fee-for-service reimbursement. Models of payment that emphasize shared savings between provider organizations and payers are necessary, but not sufficient, conditions for these low-cost, high value services to flourish.

The importance to providers of identifying services that both improve health and lower cost, but have been infrequently reimbursed by payers, cannot be understated. To our knowledge, however, the extent to which these types of health care services exist is unknown. How common are services that improve health and lower costs but are still infrequently reimbursed? Data from the Tufts Cost Effectiveness Registry shed some light on this question.8 Since 1976, the registry has summarized cost effectiveness evidence from thousands of studies of health care interventions, including treatments that have historically been eligible for reimbursement by payers as well as treatments that have received little, if any, reimbursement. For example, the registry includes cost-effectiveness information on low-cost reimbursed treatments like metformin and hydrochlorothiazide, as well as low-cost interventions that are infrequently reimbursed, such as over-the-counter aspirin for secondary cardiovascular protection, oral nutritional supplements for individuals with malnutrition, and influenza vaccinations for individuals younger than 65 years. The registry also includes cost-effectiveness information on infrequently reimbursed low-cost, high-value interventions that are more relevant for hospitals, such as hand hygiene programs.

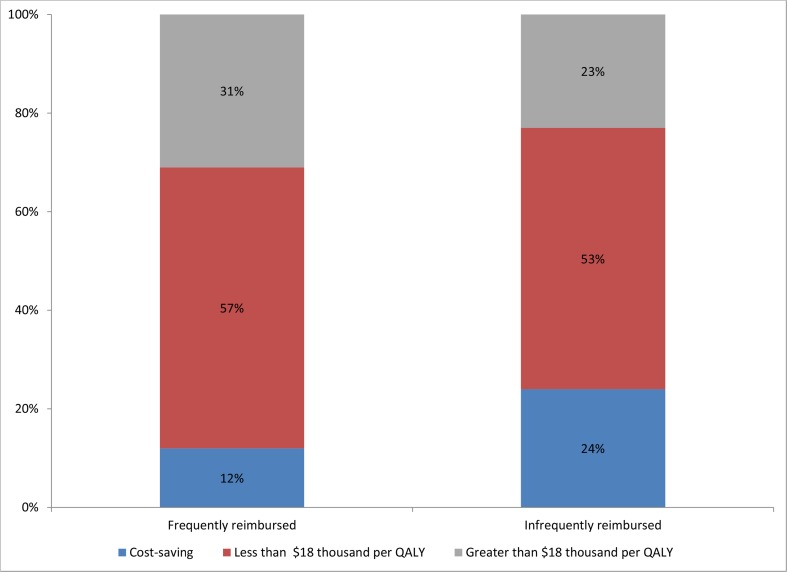

We analyzed a total of 70 cost effectiveness studies from the registry to explore whether health care interventions that are infrequently reimbursed by payers produce more, less, or similar health benefit per dollar spent, compared to widely reimbursed therapies (Fig. 1). According to the registry, treatments that are infrequently reimbursed by payers are actually more likely to be cost-saving (i.e., improve health and lower costs) than interventions that are frequently reimbursed. For example, 24 % of rarely reimbursed interventions are cost-saving compared to 12 % of reimbursed interventions (p = 0.03). Similarly, the probability of being below the median cost effectiveness ratio across the entire registry ($18,000 per quality adjusted life year saved) was 77 % for rarely reimbursed interventions and 69 % for highly reimbursed interventions. While only suggestive, these findings imply that a substantial proportion of health care interventions that are infrequently reimbursed are low cost and high value.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of cost effectiveness for selected reimbursed and non-reimbursed health care treatments included in the Tufts Cost Effectiveness Registry. Notes: QALY quality-adjusted life year. Source: Authors calculations based on data in Tuft’s cost effectiveness registry. The median incremental cost effectiveness ratio for treatments in the registry is $18,000

Although the current fee-for-service reimbursement system is detached from value, new payment models in theory offer providers greater flexibility and discretion in choosing clinical services that maximize value. These new models should not only allow, but also encourage providers to use low-cost, high-value services that have previously been infrequently reimbursed. It is important to recognize, however, that even new payment models that more closely align incentives with value may still primarily lead providers to prioritize services whose value accrues directly to the organization rather than society overall. For example, although primary care counseling about alcohol abuse is likely cost-effective and could confer some benefits to the provider organization, most of the benefits may accrue longer-term to society, and may therefore be under-incentivized.

TRANSLATING ACTIONABLE EVIDENCE INTO PRACTICE

Armed with actionable evidence on high-value services to encourage and low-value services to discourage, the main challenge for provider groups will be to translate this evidence into clinical practice through structural delivery system redesigns and other reforms—an implementation black-box that is already spurring much innovation.

Health information technology (HIT) may have a role to play. By changing defaults in computerized order entry systems, HIT can directly incorporate high-value services into clinical pathways (e.g., early mobility protocols for intensive care patients or nutrition protocols for chronically malnutritioned patients that providers must opt out of in computerized order entry). HIT can also reduce use of low-value services by requiring physicians to provide justification when ordering potentially low-value tests or treatments, an effect that may be tempered by evidence that when physicians are exposed to too many computerized alerts, they may ignore them altogether (i.e., ‘alert fatigue’).9,10 HIT can also allow for better population health management—laboratory data interfaces allow providers to create target populations who may be most likely to benefit from population health initiatives. Only a minority of provider groups are organized, however, with the necessary infrastructure to harness these and other benefits of HIT. And perhaps more importantly, although evidence on the impact of health IT on costs has been mixed and may suggest that HIT is not a panacea,11,12 much of this ambiguous impact of HIT on costs may stem from the lack financial incentives previously in place for provider groups to restrain costs. Under fee-for-service reimbursement, provider groups have not had the full incentive to harness the ability of HIT to reduce over-utilization of high-cost, low-value services or encourage unreimbursed high-value, low-cost services. Making provider groups financially accountable for the care they deliver may allow workflow-integrated IT to have its intended effect of encouraging high-value services and discouraging low-value ones. Capitated, integrated delivery systems such as Kaiser Permanente have in part approached this translation challenge through directly incorporating evidence-based guidelines into computerized order entry systems, allowing cost-effectiveness–based treatment algorithms to be seamlessly integrated into the physician’s workflow.

Other delivery system reforms may also assist provider groups in translating actionable evidence into cost-effective clinical decisions with the right payment systems in place. For example, patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs) have been widely promoted as a means to improve quality and lower costs by increasing access to primary care, improving preventive and chronic disease management, and better coordinating care. However, evidence on their success has been variable, in part due to differences in structural and payment systems across practices adopting the PCMH model. For example, in one of the largest evaluations to date, Friedberg and colleagues evaluated changes in quality, utilization, and costs associated with participation in the Southeastern Pennsylvania Chronic Care Initiative, one of the largest small-group practice medical home pilots in the United States.13 In a comparison of 32 intervention practices to 29 control practices over 3 years, this study found improvements in quality measures in only one of 11 chronic diseases (nephropathy screening in diabetes), and no changes in emergency department or hospital utilization or costs of care. A similar study of small-group–based PMCHs in Rhode Island found no improvement in quality measures or overall emergency department or hospital utilization, but an 11 % relative reduction in emergency visits for ambulatory sensitive conditions.14 Part of the failure of these PCMHs to demonstrate substantial cost savings and quality improvements may have been due to implementation shortcomings, such as patient utilization data being available to only half of participating clinicians in PCMHs, regular group-based meetings about utilization being held in less than one-third of medical homes, and hospital discharge summaries being unavailable in one-quarter of medical homes.13 Moreover, PCMHs in these demonstrations also may have not been successful in curbing utilization and spending, due to the lack of integrated delivery system and high-powered payment systems (e.g., global payment systems) involved in these initiatives. Indeed, some evidence suggests that PCMHs may have their greatest chance for success in capitated integrated delivery systems or large, single-payer community practices with strong financial incentives to reduce overuse.13–15 Thus, when coupled with financial accountability among provider groups, advanced models of primary care may yet support cost-effective clinical decisions.

In addition to advancing their structural capabilities and systems of care, provider organizations are likely to pursue other strategies for modifying physician behavior, such as physician profiling, establishment of preferred provider networks, and changes to physician compensation to directly reward more cost-effective practices.

SUMMARY

Together, payment and delivery system reforms have the potential to improve health care quality and lower costs by reducing overutilization of high-cost, low-value services and increasing use of low-cost, high-value services. For these efforts to be successful, however, actionable evidence on both types of services will need to be disseminated to provider groups, who will need to make the necessary infrastructure and delivery system changes to translate this evidence into practice. In addition, efforts to educate patients about cost-effective health care services are ongoing, and may take greater hold with growth of transparency initiatives and high-deductible health plans that encourage patients to make cost-effective health care choices. In summary, although much evidence remains to be generated and much translation into practice remains to be done, there are clear opportunities for providers to maximize value of care through the delivery and payment system reforms that are well underway.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Dr. Jena reports receipt of an award from the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health (NIH Early Independence Award, 1DP5OD017897-01). Dr. McWilliams is supported by grants from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (Clinical Scientist Development Award #2010053), Beeson Career Development Award Program (National Institute on Aging K08 AG038354 and the American Federation for Aging Research), and National Institute on Aging (P01 AG032952). Support for this research was provided by Abbott Laboratories.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Jena reports providing consulting services to Precision Health Economics, which received support from Abbott Laboratories to conduct this research. Precision Health Economics also provides research and consulting services to the life sciences industries and government. Dr. Stevens is an economist at that organization.

Contributor Information

Anupam B. Jena, Phone: 617-432-8322, Email: jena@hcp.med.harvard.edu

Warren Stevens, Email: warren.stevens@pheconomics.com

J. Michael McWilliams, Email: mcwilliams@hcp.med.harvard.edu

REFERENCES

- 1.Cassel CK, Guest JA. Choosing wisely: helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care. JAMA. 2012;307:1801–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz AL, Landon BE, Elshaug AG, Chernew ME, McWilliams JM. Measuring Low-Value Care in Medicare. JAMA Intern Med 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Elshaug AG, McWilliams JM, Landon BE. The value of low-value lists. JAMA. 2013;309:775–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palen TE, Price D, Shetterly S, Wallace KB. Comparing virtual consults to traditional consults using an electronic health record: an observational case–control study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:65. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-12-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou YY, Kanter MH, Wang JJ, Garrido T. Improved quality at Kaiser Permanente through e-mail between physicians and patients. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:1370–5. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lord RK, Mayhew CR, Korupolu R, et al. ICU early physical rehabilitation programs: financial modeling of cost savings. Critical Care Medicine. 2013;41:717–24. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182711de2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Philipson TJ, Snider JT, Lakdawalla DN, Stryckman B, Goldman DP. Impact of oral nutritional supplementation on hospital outcomes. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19:121–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tufts Cost Effectiveness Analysis Registry. 2013. (Accessed July 18, 2014, at https://research.tufts-nemc.org/cear4/.)

- 9.van der Sijs H, Aarts J, Vulto A, Berg M. Overriding of drug safety alerts in computerized physician order entry. J Am Med Informat Assoc. 2006;13:138–47. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kesselheim AS, Cresswell K, Phansalkar S, Bates DW, Sheikh A. Clinical decision support systems could be modified to reduce ‘alert fatigue’ while still minimizing the risk of litigation. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:2310–7. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adler-Milstein J, Salzberg C, Franz C, Orav EJ, Newhouse JP, Bates DW. Effect of electronic health records on health care costs: longitudinal comparative evidence from community practices. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:97–104. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-2-201307160-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adler-Milstein J, Salzberg C, Franz C, Orav EJ, Bates DW. The Impact of Electronic Health Records on Ambulatory Costs Among Medicaid Beneficiaries. Medicare & Medicaid Research Review. 2013;3:16. doi: 10.5600/mmrr.003.02.sa03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwenk TL. The patient-centered medical home: one size does not fit all. JAMA. 2014;311:802–3. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson K, Helfrich C, Sun H, et al. Implementation of the Patient-Centered Medical Home in the Veterans Health Administration: Associations With Patient Satisfaction, Quality of Care, Staff Burnout, and Hospital and Emergency Department Use. JAMA Intern Med 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Hebert PL, Liu CF, Wong ES, et al. Patient-centered medical home initiative produced modest economic results for veterans health administration, 2010–12. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:980–7. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]