ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Older persons account for the majority of hospitalizations in the United States.1 Identifying risk factors for hospitalization among elders, especially potentially preventable hospitalization, may suggest opportunities to improve primary care. Certain factors—for example, living alone—may increase the risk for hospitalization, and their effect may be greater among persons with dementia and the old-old (aged 85+).

OBJECTIVES

To determine the association of living alone and risk for hospitalization, and see if the observed effect is greater among persons with dementia or the old-old.

DESIGN

Retrospective longitudinal cohort study.

PARTICIPANTS

2,636 participants in the Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) study, a longitudinal cohort study of dementia incidence. Participants were adults aged 65+ enrolled in an integrated health care system who completed biennial follow-up visits to assess for dementia and living situation.

MAIN MEASURES

Hospitalization for all causes and for ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSCs) were identified using automated data.

KEY RESULTS

At baseline, the mean age of participants was 75.5 years, 59 % were female and 36 % lived alone. Follow-up time averaged 8.4 years (SD 3.5), yielding 10,431 approximately 2-year periods for analysis. Living alone was positively associated with being aged 85+, female, and having lower reported social support and better physical function, and negatively associated with having dementia. In a regression model adjusted for age, sex, comorbidity burden, physical function and length of follow-up, living alone was not associated with all-cause (OR = 0.93; 95 % CI 0.84, 1.03) or ambulatory care sensitive condition (ACSC) hospitalization (OR = 0.88; 95 % CI 0.73, 1.07). Among participants aged 85+, living alone was associated with a lower risk for all-cause (OR = 0.76; 95 % CI 0.61, 0.94), but not ACSC hospitalization. Dementia did not modify any observed associations.

CONCLUSION

Living alone in later life did not increase hospitalization risk, and in this population may be a marker of healthy aging in the old-old.

KEY WORDS: aging, health care delivery, ambulatory care, dementia, social support

BACKGROUND

Older adults account for the majority of acute care hospitalizations in the United States.1,2 Of special concern are reports of high rates for ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSCs),3–5 those conditions for which hospitalization may be avoidable with timely and effective primary care.6,7 A better understanding of risk factors for hospitalization among elders, especially for ACSCs, is necessary to identify opportunities to improve primary care for this expanding subgroup.

Living alone has been associated with more unnecessary days in the hospital8 and higher readmission rates,9,10 yet to our knowledge, the effect of living alone in old age on the risk for hospitalization has not been previously examined. Living alone is an established risk factor for the onset and progression of chronic disease,11,12 plausibly through its association with reduced social support.11 Social relationships, especially those formed by living together,13–15 may prevent hospitalization by enhancing coping skills, encouraging healthy behaviors, and facilitating connections with the health care system.11,16,17

The effect of living alone on risk for hospitalization may be greater in vulnerable subgroups, such as the old-old (aged 85 years or older) and persons with dementia. Few publications examine health services utilization in discrete age groups of older adults, yet those aged 85 and older have been shown to utilize emergency medical care at double the rate of younger adults.18 Older adults with dementia are hospitalized more frequently than adults without dementia for all causes and ACSCs.5,19–22 Persons with dementia who live alone are at higher risk for inadequate self-care, untreated medical conditions, and use of emergency medical services compared to those living with others.23–26

A better understanding of the relationship of living alone and risk for hospitalization can inform approaches for improving care in the outpatient setting. This study uses data from a longitudinal cohort of aging and dementia to determine if living alone is associated with acute care hospitalization in elders, the old-old and those with and without dementia. We hypothesized that living alone would increase the risk for hospitalization in older adults, and that this effect would be greater in the old-old and persons with dementia.

METHODS

Setting and Design

All participants were enrolled in the Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) cohort study, a population-based longitudinal study of the incidence of and risk factors for dementia.27,28 The ACT study enrolls members of the Group Health Cooperative (GHC), an integrated health care delivery system in the Pacific Northwest. At the time of enrollment, participants were aged 65 years or older, cognitively intact, and not residing in a nursing home. As described in prior publications,27,28 all ACT participants complete biennial follow-up visits to assess cognition and health status until the diagnosis of dementia, death or study disenrollment. Persons identified as having dementia complete at least one annual follow-up visit to confirm dementia status and type.

In this study, we used a retrospective longitudinal cohort design to assess the impact of living alone on all-cause and ACSC hospitalizations among ACT participants. Follow-up began at first enrollment in ACT and ended at death or end of study follow-up.

Participants

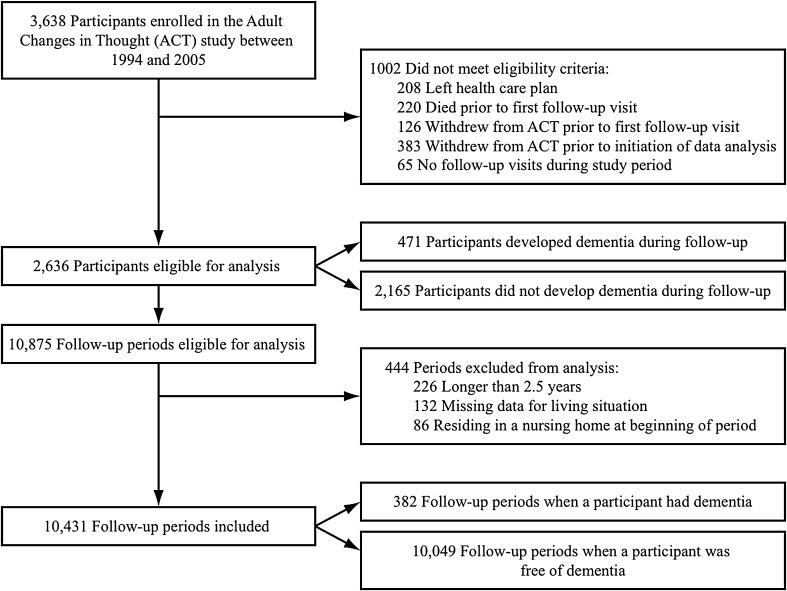

The data set included participants who were enrolled in ACT between 1 February 1994 and 31 December 2005, and who were followed until 31 December 2007. Participants were included if they had completed at least one ACT follow-up visit while enrolled in GHC and remained enrolled in ACT when data analysis was initiated per institutional review board (IRB) regulations (Fig. 1). Two hundred and eight participants (5.7 %) were excluded because they left the health plan, 220 (6.0 %) died, 129 (3.5 %) withdrew from ACT prior to follow-up, and 383 (10.5 %) withdrew from ACT prior to data analysis. We divided each participant’s follow-up into periods approximately 2 years in length, timed to coincide with the biennial ACT visits. We excluded periods that were longer than 2.5 years due to late or missed visits (2.0 %) to avoid outdated covariate information. We also excluded periods that were missing living situation data (1.4 %) or that included a participant residing in a nursing home (0.5 %), since we were interested in hospitalizations among community-dwelling elders. This study was approved by the Group Health Institutional Review Board. All participants provided written informed consent for ACT assessments at the time of enrollment into ACT.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of participants and follow-up periods included in analysis.

MEASURES

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was all-cause hospitalization, measured as any admission requiring an overnight stay during each follow-up period. Automated hospitalization files, validated and utilized in prior research, were used to identify admissions.29

The secondary outcome of ACSC hospitalization included any admission with a primary discharge diagnostic code of angina, asthma, bacterial pneumonia, cellulitis, congestive heart failure exacerbation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation, dehydration, diabetes, duodenal ulcer, ear/nose/throat infection, gastric ulcer, gastroenteritis, hypertension, hypoglycemia, hypokalemia, influenza, malnutrition, peptic ulcer, seizure disorder, or urinary tract infection. These conditions were selected based on publications of ACSCs in the elderly.30,31

Independent Variable

Living alone was the main independent variable and measured at the beginning of each follow-up period. Participants categorized their living situation as: (1) live with spouse only; (2) live with spouse and other relatives; (3) live with other relatives or friends; (4) live with other unrelated individuals (e.g., adult family home); (5) live in nursing home; (6) live alone; (7) refused/do not know/missing. Prior research suggests that living with another individual is more predictive of social support than the relationship of the individuals with whom one lives, and participants reported living with unrelated individuals during a small proportion of periods (2.6 %).13–15 Therefore, we categorized living situation as a binary variable to compare living alone versus living with others.

Effect Modifier

Dementia was included as a potential effect modifier of the association between living alone and hospitalization. ACT participants underwent biennial cognitive screening using the Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI).32 As published previously,5,28 participants scoring below 86 on the CASI or demonstrating symptoms of cognitive impairment underwent a rigorous dementia diagnostic evaluation to reach a confirmed diagnosis.33–35 We also examined sex as a potential effect modifier, given evidence that older men experience worse health outcomes than older women when living alone.12,36

Covariates

Primary confounders of the association between living alone and risk for hospitalization included age,1,30,31 sex,37,38 comorbidity burden,39–44 and physical function8,45 assessed at the time of enrollment in ACT. Secondary confounders included additional sociodemographic (race, income, educational level) and comorbid conditions (depression, difficulty with one or more activities of daily living, and self-reported heart disease, diabetes and cancer).

Comorbidity burden was measured using the RxRisk Score, a risk assessment instrument that uses automated ambulatory pharmacy data to identify chronic conditions based on at least one pharmacy dispense over a 1-year period.5,46 The RxRisk Score provides a valid estimate of chronic disease burden and future health services utilization when compared to diagnosis-based case mix models.47,48 Dementia or associated medications are not included in the algorithm. A Performance-Based Physical Function (PPF) score was calculated from four physical function tests (10-ft timed walk, chair-stand time, standing balance and grip strength) that were rated from 0 to 4 and summed for a best score of 16.49

Additional sociodemographic characteristics, health conditions and behaviors were collected from self-reports upon enrollment into ACT and at each follow-up period (Table 1). Social support was measured as the sum of the scores from the 6-item version of the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL).50,51 Depression was defined as a score of ten or more out of a total score of 30 on the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale.52

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Health Characteristics of all Participants (n = 2,636) and Participants Aged 85+ (n = 226)

| All Participants | Participants Aged 85 + * | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, n (%) | ||

| 65–74 | 1,374 (52.1) | – |

| 75–84 | 1,036 (39.3) | – |

| 85+ | 226 (8.6) | 226 (100.0) |

| Female, n (%) | 1,554 (59.0) | 163 (72.1) |

| Nonwhite, n (%) | 243 (9.2) | 11 (4.9) |

| Married, living as, n (%) | 1,437 (54.5) | 60 (26.6) |

| Income < $15,000, n (%) | 408 (15.5) | 62 (27.4) |

| High School Graduate, n (%) | 2,117 (80.3) | 165 (73.0) |

| Difficulty with 1+ ADLs, n (%) | 581 (22.0) | 70 (31.0) |

| PPF Score†, mean (SD) | 10.4 (2.2) | 9.7 (2.7) |

| Self-reported health, poor, n (%) | 45 (1.7) | 7 (3.10) |

| Depression‡, n (%) | 273 (10.4) | 26 (11.7) |

| Diabetes (ever reported), n (%) | 248 (9.4) | 15 (6.7) |

| Cancer (ever reported), n (%) | 450 (17.1) | 43 (19.0) |

| Heart Disease§, n (%) | 512 (19.5) | 54 (24.1) |

| Smoking Status, n (%) | ||

| Never | 1,252 (47.6) | 128 (56.6) |

| Past | 1,230 (46.7) | 91 (40.3) |

| Current | 151 (5.7) | 7 (3.1) |

| Developed Dementia, n (%) | 471 (17.9) | 71 (31.4) |

| Social Support||, mean (SD) | 8.1 (2.6) | 8.3 (2.4) |

| RxRisk Score¶, USD, mean (SD) | 4,439.9 (2,929.7) | 5,285.2 (2,650.1) |

| Living Situation, n (%) | ||

| Alone | 956 (36.3) | 138 (61.1) |

| Spouse Only | 1,249 (47.4) | 54 (23.9) |

| Spouse and Other Relatives | 158 (6.0) | 3 (1.3) |

| Other Relatives and Friends | 225 (8.5) | 18 (8.0) |

| Other Unrelated Individuals | 42 (1.6) | 10 (4.4) |

| Nursing Home | 5 (0.2) | 3 (1.3) |

| Ever Hospitalized during follow-up, n (%) | 1,644 (62.4) | 171 (75.7) |

*These data represent baseline measures from 226 participants who were aged 85 years or older at baseline; however, follow-up periods from participants who reached age 85 or older during study follow-up were included in subsequent analyses

†PPF Score is the Performance-Based Physical Function Score ranging from 0 to 16. A higher PPF Score indicates better physical function

‡Depression is flagged as present for a score of ≥ 10 on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)

§Heart disease is defined as prevalent myocardial infarction, angina, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), angioplasty

||Social support is measured by the mean score on six items from the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL), where each item is scored on a scale of 1–4 for a total potential score of 24. A lower score indicates higher levels of interpersonal support

¶The RxRisk Score is measured in U.S. dollars. A lower RxRisk Score indicates a lower comorbidity burden

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Baseline demographic characteristics were tabulated for all participants and those aged 85 years or older. We compared the proportion of all-cause and ACSC admissions in periods when participants were living alone versus living with others using a generalized estimating equation (GEE) logistic regression with empirical standard errors to account for within-person correlation of multiple follow-up periods. For each outcome, we fit an unadjusted model; a model adjusted for primary covariates [age, sex, comorbidity burden (log-transformed RxRisk Score), physical function (PPF Score) and period duration]; and adjusted models with and without sex and dementia status as interaction terms with living alone. We added each group of secondary confounders to the adjusted model; however, since the results did not differ appreciably (odds ratios differed < 10 %), we elected to retain our original model adjusted only for primary confounders. Separate adjusted models were fit for participants aged 85 years or older. Finally, to ensure that hospitalization at the end of life did not bias the findings, multivariate analyses were repeated excluding periods during which a participant died. Only two observations were excluded from adjusted models because of missing data. All analyses were performed using STATA version 11.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics at Baseline

Of the 3,638 participants enrolled in ACT between 1994 and 2005, a total of 2,636 subjects were included in this study (Fig. 1). Participants were followed for an average of 8.4 years (SD 3.5) and the average duration of a follow-up period was 2.0 years (mean 703.0 days, SD 118.1). Participants who developed dementia were followed for one follow-up period after diagnosis.

Table 1 reports characteristics of all participants (N = 2,636) and participants aged 85 or older at the time of enrollment in ACT. The mean age of participants when enrolled was 75.5 years (SD 6.3). Participants were predominantly female, white, and had at least a high school degree. Thirty-eight percent of all participants (n = 992) were never hospitalized during study follow-up. A larger proportion of old-old enrollees were female, unmarried, and living alone, and had a higher comorbidity burden at baseline compared to the entire sample.

Participant Characteristics when Living Alone Versus Living with Others

Given that living situation and other covariates changed over time, biennial measures were compared for the primary analysis. Table 2 compares periods during which participants were living alone versus living with others for all periods (N = 10,431) and for periods when participants were aged 85 or older (n = 1,738). Approximately one-quarter of the periods included an all-cause hospitalization, and about 6 % of the periods included an ACSC hospitalization regardless of living situation. The percentage of periods including a hospitalization increased as participants aged over 85 (all-cause: 38.8 %, ACSC: 13.0 %). Periods when a participant was aged 85 or older were 1.65 (95 % CI 1.46, 1.84; p < 0.01) times as likely as periods when a participant was younger than 85 to include an all-cause hospitalization and 2.22 (95 % CI 1.90, 2.69; p < 0.01) times as likely to include an ACSC hospitalization.

Table 2.

Comparison of Participant Characteristics During Periods when Living Alone Versus Living with Others: All Periods (2a) and Periods During Which Participants Were Aged 85+ (2b)*

| 2a | All Follow-Up Periods | ||||

| Living Alone (n = 4,100) | Living with Others (n = 6,331) | Unadjusted p value | Age & Sex Adjusted p value† | All Periods (N = 10,431) | |

| All-Cause Admission, n (%) | 1,062 (25.9) | 1,607 (25.4) | 0.55 | 0.12 | 2,669 (25.6) |

| ACSC Admission, n (%) | 242 (5.9) | 393 (6.2) | 0.52 | 0.05 | 635 (6.1) |

| Age‡, n (%) | |||||

| 65–74 | 1,019 (24.9) | 2,295 (36.3) | < 0.01 | – | 3,314 (31.8) |

| 75–84 | 2,129 (51.9) | 3,250 (51.3) | – | 5,379 (51.6) | |

| 85+ | 952 (23.2) | 786 (12.4) | – | 1,738 (16.6) | |

| Female, n (%) | 3,211 (78.3) | 3,000 (47.4) | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 6,211 (59.5) |

| Nonwhite, n (%) | 287 (7.0) | 537 (8.5) | 0.01 | 0.32 | 824 (7.9) |

| Married, living as‡, n (%) | 147 (3.7) | 4,925 (80.6) | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 5,072 (50.3) |

| Income < $15,000‡, n (%) | 927 (22.6) | 457 (7.2) | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 1,384 (13.3) |

| High School Graduate, n (%) | 3,356 (81.9) | 5,073 (80.2) | 0.09 | 0.20 | 8,429 (80.9) |

| Difficulty with 1+ ADL#, n (%) | 1,302 (31.8) | 1,756 (27.7) | < 0.01 | 0.06 | 3,058 (29.3) |

| PPF Score‡§, mean (SD) | 9.5 (2.9) | 9.7 (3.0) | < 0.01 | 0.04 | 9.6 (2.9) |

| Poor self-reported health#, n (%) | 102 (2.5) | 190 (3.0) | 0.12 | 0.08 | 292 (2.8) |

| Depression‡||, n (%) | 475 (11.8) | 574 (9.2) | < 0.01 | 0.12 | 1,049 (10.3) |

| Diabetes‡ (ever reported), n (%) | 406 (10.0) | 774 (12.3) | < 0.01 | 0.08 | 1,180 (11.4) |

| Cancer‡ (ever reported), n (%) | 921 (22.6) | 1,509 (24.1) | 0.08 | 0.03 | 2,430 (23.5) |

| Heart Disease¶, n (%) | 961 (23.6) | 1,601 (25.6) | 0.03 | 0.71 | 2,562 (24.8) |

| Smoking Status‡, n (%) | |||||

| Never | 1,990 (48.8) | 2,963 (47.2) | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 4,953 (47.8) |

| Past | 1,870 (45.9) | 3,072 (49.0) | 4,942 (47.7) | ||

| Current | 217 (5.3) | 241 (3.8) | 458 (4.4) | ||

| Dementia‡, n (%) | 118 (2.9) | 264 (4.2) | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 382 (3.7) |

| Social Support‡#, mean (SD) | 8.1 (2.7) | 7.8 (2.4) | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 7.9 (2.5) |

| RxRisk Score**, USD, mean (SD) | 4,111.0 (2,365.5) | 4,283.5 (2,834.6) | < 0.01 | 0.34 | 4,232.4 (2,685.1) |

| 2b | Follow-Up Periods during which Participants were Aged 85+ | ||||

| Living Alone (n = 952) | Living with Others (n = 786) | Unadjusted p-value | Age & Sex Adjusted p-value | All Periods (n = 1,738) | |

| All-Cause Admission, n (%) | 340 (35.7) | 334 (42.5) | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 674 (38.8) |

| ACSC Admission, n (%) | 112 (11.8) | 114 (14.5) | 0.09 | 0.12 | 226 (13.0) |

| Age, n (%) | |||||

| 65–74 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 75–84 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 85+ | – | – | – | – | 100.0 |

| Female, n (%) | 773 (81.2) | 391 (49.8) | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 1,164 (67.0) |

| Nonwhite, n (%) | 36 (3.8) | 46 (5.9) | 0.04 | 0.39 | 82 (4.7) |

| Married, living as, n (%) | 32 (3.5) | 436 (59.1) | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 468 (28.5) |

| Income < $15,000, n (%) | 233 (24.5) | 87 (11.1) | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 320 (18.4) |

| High School Graduate, n (%) | 709 (74.5) | 594 (75.6) | 0.13 | 0.50 | 1,303 (75.0) |

| Difficulty with 1+ ADL, n (%) | 444 (46.6) | 390 (49.6) | 0.22 | < 0.01 | 834 (48.0) |

| PPF Score, mean (SD) | 8.8 (3.3) | 8.2 (3.9) | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 8.5 (3.6) |

| Poor self-reported health, n (%) | 41 (4.4) | 31 (4.1) | 0.75 | 0.94 | 72 (4.2) |

| Depression, n (%) | 110 (12.0) | 99 (13.6) | 0.35 | 0.22 | 209 (12.7) |

| Diabetes (ever reported), n (%) | 89 (9.5) | 61 (8.0) | 0.30 | 0.56 | 150 (8.8) |

| Cancer (ever reported), n (%) | 248 (26.3) | 227 (30.0) | 0.08 | 0.43 | 475 (28.0) |

| Heart Disease, n (%) | 274 (29.2) | 276 (36.5) | < 0.01 | 0.09 | 550 (32.5) |

| Smoking Status, n (%) | |||||

| Never | 544 (57.8) | 416 (54.8) | 0.04 | 0.06 | 960 (56.5) |

| Past | 375 (39.9) | 327 (43.1) | 702 (41.3) | ||

| Current | 22 (2.3) | 16 (2.1) | 38 (2.2) | ||

| Dementia, n (%) | 61 (6.4) | 115 (14.6) | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 176 (10.2) |

| Social Support, mean (SD) | 8.1 (2.6) | 7.8 (2.5) | 0.02 | < 0.01 | 7.9 (2.6) |

| RxRisk Score, USD, mean (SD) | 4,639.9 (2,110.0) | 5,201.4 (2,697.5) | < 0.01 | 0.16 | 4,893.5 (2,408.8) |

*Follow-up periods rather than participants are the unit of analysis in this table. Thus, all categorical variables are reported as the percentage (%) of periods when each characteristic was present and continuous variables are averaged across follow-up periods. For example, 25.9 % of periods when subjects were living alone included an all-cause admission. The mean PPF score averaged across all follow-up periods was 9.6 (SD 2.9)

† P value tests if the percentages or means in periods when a participant was living alone versus not living alone differ, calculated using a logistic regression with period as the unit of analysis, controlling for age and sex, and accounting for repeated observations using GEE with empirical standard errors. Tests in age groups compare age 75+ years versus age < 75 and in smoking status compare ever versus never smoked. Values in bold are statistically significant at the p = 0.05 level

‡Time-varying variables were measured during biennial follow-up visits, and the updated values for each follow-up period were used in analysis

§PPF Score is the Performance-Based Physical Function Score ranging from 0 to 16. A higher PPF Score indicates better physical function

||Depression is flagged as present for a score of ≥ 10 on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)

¶Heart disease is defined as prevalent myocardial infarction, angina, coronary artery bypass grafting, and/or angioplasty

#Social support is measured by the mean score on the 6-item Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL), where each item is scored on a scale of 1–4 for a total potential score of 24. A lower score indicates higher levels of interpersonal support

**The RxRisk Score is measured in U.S. dollars. A lower RxRisk Score indicates a lower comorbidity burden

Across all follow-up periods, when participants were living alone they were more likely to be older, female, white, unmarried, and non-smokers than those living with others. Those living alone also reported lower perceived social support and demonstrated worse physical performance, but were less likely to carry a diagnosis of dementia than those living with others. A larger proportion of participants aged 85 or older were living alone (54.8 %) compared to the entire cohort (39.3 %) and those under age 85 (36.2 %). Participants aged 85 or older and living alone demonstrated better physical function but lower perceived social support compared to those living with others.

Association of Living Alone and Risk for Hospitalization

Table 3 presents unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for the association between living alone and risk for all-cause and ACSC hospitalization. Again, period was the unit of analysis. In this cohort of adults, no association was found between living alone and risk for all-cause or ACSC hospitalization when controlling for age, sex, comorbidity burden, physical function and period duration.

Table 3.

Association of Living Alone and Risk for All-Cause or ACSC Hospitalization

| Unadjusted OR (95 % CI) | Unadjusted p value | Adjusted OR* (95 % CI) | Adjusted p value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Ages | ||||

| All-Cause Hospitalization | 1.03 (0.93, 1.14) | 0.59 | 0.93 (0.84, 1.03) | 0.19 |

| ACSC Hospitalization | 0.95 (0.79, 1.13) | 0.56 | 0.88 (0.73, 1.07) | 0.19 |

| Age 85+ | ||||

| All-Cause Hospitalization | 0.75 (0.59, 0.92) | < 0.01 | 0.76 (0.61, 0.94) | 0.01 |

| ACSC Hospitalization | 0.79 (0.59, 1.04) | 0.09 | 0.89 (0.65, 1.20) | 0.44 |

*Models were adjusted for age, sex, comorbidity burden (log-transformed RxRisk Score), physical function (PPF Score), and length of follow-up period

† P value tests if the percentages in periods when a participant was living alone versus not living alone differ, calculated using a logistic regression with period as the unit of analysis and accounting for repeated observations using GEE with empirical standard errors. Risk measures in bold are statistically significant at the p = 0.05 level

Among individuals aged 85 or older, the odds of having an all-cause hospitalization when living alone were 0.76 (95 % CI 0.61, 0.94; p = 0.01) as much as when living with others. ACSC hospitalization was not significantly associated with living status in this age group.

Excluding periods in which a person died strengthened the observed association of living alone and risk for all-cause hospitalization in the old-old (OR = 0.69; 95 % CI 0.54, 0.87; p < 0.01), but did not substantially alter the risk measure for all participants or impact the association of ACSC hospitalization and living alone. Neither sex nor dementia modified the association of living alone and hospitalization among all participants or those aged 85 years or older (p > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Our main hypotheses, that living alone would be associated with an increased risk for all-cause and ACSC hospitalization, were not supported for this sample as a whole. Although those living alone reported significantly lower perceived social support than those living with others, there was notable overlap between the scores of the two groups, and those living alone may have received support in areas not captured by our measures. For example, participants may have had access to home health care, community-based senior programs, or non-physician health professionals. Such protective factors may account for the lack of an observed association between living situation and hospitalization in this cohort.

We did not anticipate discovering a lower risk for all-cause hospitalization among adults aged 85 or older who were living alone compared to those living with others. We predicted a higher risk for hospitalization among the oldest participants living alone, since the old-old are frequently at risk for frailty and associated health problems.53 In contrast, by examining the old-old as a subgroup, we likely highlighted a resilient group of adults who developed less comorbidity, allowing them to continue living independently. Participants living alone and aged 85 or older were less likely to have dementia or heart disease and had a lower comorbidity burden compared to those living with others. Accumulation of chronic conditions and cognitive impairment may lead older adults to move in with others or into an institution, while also placing them at a higher risk for hospitalization. Yet even in the old-old, we did not find a significant association between living situation and risk for ACSC hospitalization. Incentivizing preventive, collaborative care and reducing acute care hospitalizations are integral to GHC’s approach to care, and living situation may not significantly impact the risk for ACSC hospitalization in elders receiving proactive ambulatory care.

The risk for hospitalization in this sample increased with age, with the odds of an all-cause hospitalization increasing by 65 % and the odds of an ACSC hospitalization doubling in those aged 85 years or older compared to those under 85. As adults in this study aged, living alone became more common, evidenced by a higher proportion of follow-up periods during which a participant aged 85 or older was living alone compared to the entire cohort. Although a larger proportion of older women were living alone, there was no significant difference in the effect of living alone on risk for hospitalization between men and women in this cohort.

The presence of dementia also did not alter the association of living alone and risk for hospitalization in this cohort, likely due to the limited follow-up of participants who developed dementia. In this study, hospitalization data were examined for the first 2 years following dementia diagnosis, since living situation measures were not updated after diagnosis. As a result, less than 4 % of the follow-up periods analyzed included a participant with dementia, as opposed to 9 % if we had included all follow-up periods for these participants. In contrast, a prior publication examining rates of hospitalization in this cohort reported higher rates of all-cause and ACSC hospitalization in participants with dementia (followed an average of 9.6 years) compared to those who remained dementia-free.5 Since rates of hospitalization and the risks associated with living alone may increase with dementia severity,25,26,54,55 the restricted follow-up of participants in this study probably limited our ability to detect a relationship between living situation and hospitalization in this subgroup.

A number of multivariate logistic regression models exist to predict hospitalization or rehospitalization of older adults.56–60 We considered similar risk factors when developing our model, yet aimed to interpret the strength of the association between living alone and hospitalization, rather than contribute another predictive algorithm. We did not include prior hospitalization as a covariate because we analyzed time periods within subjects. We also did not have information about prior use of other health services such as physician visits.

This study has several limitations. Participants may be healthier than the general population, due to access to an integrated delivery system with a preventive approach to managing chronic conditions and readily available alternatives to hospitalization (e.g., 24-h nurse consultation hotline). Furthermore, participants reside in the Puget Sound region, with access to resources unique to a metropolitan area. Living situation was measured biennially and may not reflect the living arrangement at the time of hospitalization. Finally, longitudinal follow-up of participants who developed dementia would have permitted a more thorough examination of transitions in living situation.

This study also has a number of notable strengths. It is the first study to reveal an intriguing phenomenon of a reduced risk of hospitalization in the old-old living alone, and one of the first to examine hospitalization patterns in the 85 and older subgroup. It also adds to the small amount of literature addressing longitudinal changes in living situation among older adults,13,15,23,41,43,61,62 by illustrating an increasing risk for hospitalization and prevalence of persons living alone as adults age. The sample size was large and attrition rates low (estimated to be < 5 % in the ACT cohort), with an average follow-up duration of 8.4 years across all participants. Automated hospitalization files permitted complete capture and accurate classification of hospitalization data, and dementia diagnoses were assigned empirically rather than via retrospective claims-based data.

Our findings suggest that living alone in advanced age may not always be a risk factor for hospitalization, and for some could be a marker of healthy aging. Living alone likely does present a challenge to certain older adults, but identifying protective factors may generate opportunities to support healthy aging. The trend toward living solo has grown as disability rates decline,63 and a preference for aging in place gains popularity.64 Understanding factors that permit the old-old to continue to live alone, in addition to factors that lead to hospitalization, can contribute to the design of outpatient care models that keep older adults independent and healthy.

Acknowledgements

ACT is supported by NIA grant UO1 AG 06781 (Principal Investigator: Dr. Larson).

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Larson receives royalties from UptoDate®. All other authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.DeFrances CJ, Lucas CA, Buie VC, Golosinskiy A. 2006 National Hospital Discharge Survey. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Health Statistics Reports. 2008;5:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Hospital Discharge Survey. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Data highlights- selected tables; number and rate of discharges by sex and age; 2012 Aug 28. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhds/nhds_products.htm. Accessed April 16, 2014.

- 3.Jiang HJ, Wier LM, Potter D, Burgess J. Potentially Preventable Hospitalizations among Medicare-Medicaid Dual Eligibles, 2008: Statistical Brief #96. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville (MD): Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (US); 2006. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK52652/. Accessed April 16, 2014. [PubMed]

- 4.Pfuntner A, Wier LM, Stocks C. Most Frequent Conditions in U.S. Hospitals, 2010: Statistical Brief #148. 2006. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK127490/. Accessed April 16, 2014. [PubMed]

- 5.Phelan EA, Borson S, Grothaus L, Balch S, Larson EB. Association of incident dementia with hospitalizations. JAMA. 2012;307(2):165–172. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bindman AB, Grumbach K, Osmond D, et al. Preventable hospitalizations and access to health care. JAMA. 1995;274(4):305–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Billings J, Zeitel L, Lukomnik J, Carey TS, Blank AE, Newman L. Impact of socioeconomic status on hospital use in New York City. Health Aff (Millwood) 1993;12(1):162–173. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.12.1.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ingold BB, Yersin B, Wietlisbach V, Burckhardt P, Bumand B, Büla CJ. Characteristics associated with inappropriate hospital use in elderly patients admitted to a general internal medicine service. Aging (Milano) 2000;12(6):430–438. doi: 10.1007/BF03339873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy BM, Elliott PC, Le Grande MR, et al. Living alone predicts 30-day hospital readmission after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2008;15(2):210–215. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3282f2dc4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Iorio A, Longo AL, Mitidieri Costanza A, et al. Characteristics of geriatric patients related to early and late readmissions to hospital. Aging (Milano) 1998;10(4):339–346. doi: 10.1007/BF03339797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lett HS, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Strauman TJ, Robins C, Sherwood A. Social support and coronary heart disease: epidemiologic evidence and implications for treatment. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(6):869–878. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188393.73571.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmaltz HN, Southern D, Ghali WA, et al. Living alone, patient sex and mortality after acute myocardial infarction. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(5):572–578. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0106-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tennstedt SL, Crawford S, McKinlay JB. Determining the pattern of community care: is coresidence more important than caregiver relationship? J Gerontol. 1993;48(2):S74–83. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.2.s74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chappell NL. Living arrangements and sources of caregiving. J Gerontol. 1991;46(1):S1–8. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.1.s1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lund R, Due P, Modvig J, Holstein BE, Damsgaard MT, Andersen PK. Cohabitation and marital status as predictors of mortality–an eight year follow-up study. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(4):673–679. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00219-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DiMatteo MR. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2004;23(2):207–218. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haslbeck JW, McCorkle R, Schaeffer D. Chronic illness self-management while living alone in later life: a systematic integrative review. Research on Aging. 2012;34(5):507–547. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carmel S, Anson O, Levin M. Emergency department utilization: a comparative analysis of older-adults, old and old-old patients. Aging (Milano) 1990;2(4):387–393. doi: 10.1007/BF03323957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albert SM, Costa R, Merchant C, Small S, Jenders RA, Stern Y. Hospitalization and Alzheimer’s disease: results from a community-based study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54(5):M267–271. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.5.m267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bynum JPW, Rabins PV, Weller W, Niefeld M, Anderson GF, Wu AW. The relationship between a dementia diagnosis, chronic illness, Medicare expenditures, and hospital use. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(2):187–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao Y, Kuo T-C, Weir S, Kramer MS, Ash AS. Healthcare costs and utilization for Medicare beneficiaries with Alzheimer’s. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:108. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Natalwala A, Potluri R, Uppal H, Heun R. Reasons for hospital admissions in dementia patients in Birmingham, UK, during 2002–2007. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;26(6):499–505. doi: 10.1159/000171044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nourhashemi F, Amouyal-Barkate K, Gillette-Guyonnet S, Cantet C, Vellas B. Living alone with Alzheimer’s disease: cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis in the REAL.FR Study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2005;9(2):117–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miranda-Castillo C, Woods B, Orrell M. People with dementia living alone: what are their needs and what kind of support are they receiving? Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(4):607–617. doi: 10.1017/S104161021000013X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tierney MC, Snow WG, Charles J, Moineddin R, Kiss A. Neuropsychological predictors of self-neglect in cognitively impaired older people who live alone. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(2):140–148. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000230661.32735.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tierney MC, Charles J, Naglie G, Jaglal S, Kiss A, Fisher RH. Risk factors for harm in cognitively impaired seniors who live alone: a prospective study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(9):1435–1441. doi: 10.1111/j.0002-8614.2004.52404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larson EB, Kukull WA, Teri L, et al. University of Washington Alzheimer’s Disease Patient Registry (ADPR): 1987–1988. Aging (Milano) 1990;2(4):404–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kukull WA, Higdon R, Bowen JD, et al. Dementia and Alzheimer disease incidence: a prospective cohort study. Arch Neurol. 2002;59(11):1737–1746. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.11.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saunders KW, Davis RL, Stergachis A. Pharmacoepidemiology. 4. Hoboken: Wiley; 2005. Group Health Cooperative; pp. 223–240. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Culler SD, Parchman ML, Przybylski M. Factors related to potentially preventable hospitalizations among the elderly. Med Care. 1998;36(6):804–817. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199806000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCall N, Harlow J, Dayhoff D. Rates of hospitalization for ambulatory care sensitive conditions in the Medicare + Choice population. Health Care Financ R. 2001;22(3):127–146. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teng EL, Hasegawa K, Homma A, et al. The Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI): a practical test for cross-cultural epidemiological studies of dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 1994;6(1):45–58. doi: 10.1017/s1041610294001602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jorm AF, Korten AE. Assessment of cognitive decline in the elderly by informant interview. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;152:209–213. doi: 10.1192/bjp.152.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis MA, Neuhaus JM, Moritz DJ, Segal MR. Living arrangements and survival among middle-aged and older adults in the NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(3):401–406. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.3.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kasper J. Aging alone: profiles and projections, a report of the Commonwealth Fund Commission on Elderly People Living Alone. Washington: Commonwealth Fund; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klinenberg, E, Torres, S, Portacolone, E. Aging alone in America: a briefing paper prepared for the Council on Contemporary Families for Older Americans month May 2012. 2012. Available at: http://www.contemporaryfamilies.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/2012_Briefing_Klinenberg_Aging-alone-in-america.pdf. Accessed April 16, 2014.

- 39.Walker AE. Multiple chronic diseases and quality of life: patterns emerging from a large national sample, Australia. Chronic Illn. 2007;3(3):202–218. doi: 10.1177/1742395307081504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Magaziner J, Cadigan DA, Hebel JR, Parry RE. Health and living arrangements among older women: does living alone increase the risk of illness? J Gerontol. 1988;43(5):M127–133. doi: 10.1093/geronj/43.5.m127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Worobey JL, Angel RJ. Functional capacity and living arrangements of unmarried elderly persons. J Gerontol. 1990;45(3):S95–101. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.3.s95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Putnam KG, Buist DSM, Fishman P, et al. Chronic disease score as a predictor of hospitalization. Epidemiology. 2002;13(3):340–346. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200205000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Landi F, Onder G, Cesari M, et al. Comorbidity and social factors predicted hospitalization in frail elderly patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(8):832–836. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Inouye SK, Zhang Y, Jones RN, et al. Risk factors for hospitalization among community-dwelling primary care older patients: development and validation of a predictive model. Med Care. 2008;46(7):726–731. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181649426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jacobs JM, Rottenberg Y, Cohen A, Stessman J. Physical activity and health service utilization among older people. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(2):125–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fishman PA, Goodman MJ, Hornbrook MC, Meenan RT, Bachman DJ, O’Keeffe Rosetti MC. Risk adjustment using automated ambulatory pharmacy data: the RxRisk model. Med Care. 2003;41(1):84–99. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sloan KL, Sales AE, Liu C-F, et al. Construction and characteristics of the RxRisk-V: a VA-adapted pharmacy-based case-mix instrument. Med Care. 2003;41(6):761–774. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000064641.84967.B7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huntley AL, Johnson R, Purdy S, Valderas JM, Salisbury C. Measures of Multimorbidity and Morbidity Burden for Use in Primary Care and Community Settings: A Systematic Review and Guide. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(2):134–141. doi: 10.1370/afm.1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang L, Larson EB, Bowen JD, van Belle G. Performance-based physical function and future dementia in older people. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1115–1120. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarck T, Hoberman H. Measuring the functional components of social support. In: Sarason IG, Sarason BR, editors. Social support: Theory, research, and application. The Hague, Holland: Martinus Nijhoff; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martire LM, Schulz R, Mittelmark MB, Newsom JT. Stability and change in older adults’ social contact and social support: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1999;54(5):S302–311. doi: 10.1093/geronb/54b.5.s302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) Am J Prev Med. 1994;10(2):77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ferrer A, Badia T, Formiga F, et al. Frailty in the oldest old: prevalence and associated factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(2):294–296. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Balardy L, Voisin T, Cantet C, Vellas B. Predictive factors of emergency hospitalisation in Alzheimer’s patients: results of one-year follow-up in the REAL.FR Cohort. J Nutr Health Aging. 2005;9(2):112–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Caspi E, Silverstein NM, Porell F, Kwan N. Physician outpatient contacts and hospitalizations among cognitively impaired elderly. Alzheimers Dement. 2009;5(1):30–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2008.05.2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boult C, Dowd B, McCaffrey D, Boult L, Hernandez R, Krulewitch H. Screening elders for risk of hospital admission. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41(8):811–817. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb06175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Billings J, Dixon J, Mijanovich T, Wennberg D. Case finding for patients at risk of readmission to hospital: development of algorithm to identify high risk patients. BMJ. 2006;333(7563):327. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38870.657917.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Billings J, Blunt I, Steventon A, Georghiou T, Lewis G, Bardsley M. Development of a predictive model to identify inpatients at risk of re-admission within 30 days of discharge (PARR-30). BMJ Open. 2012;2(4). doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Bottle A, Aylin P, Majeed A. Identifying patients at high risk of emergency hospital admissions: a logistic regression analysis. J R Soc Med. 2006;99(8):406–414. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.99.8.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Howell S, Coory M, Martin J, Duckett S. Using routine inpatient data to identify patients at risk of hospital readmission. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:96. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Michael YL, Berkman LF, Colditz GA, Kawachi I. Living arrangements, social integration, and change in functional health status. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153(2):123–131. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nihtilä E, Martikainen P. Why older people living with a spouse are less likely to be institutionalized: the role of socioeconomic factors and health characteristics. Scand J Public Health. 2008;36(1):35–43. doi: 10.1177/1403494807086421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Manton KG. Recent declines in chronic disability in the elderly U.S. population: risk factors and future dynamics. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:91–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aging In Place: A State Survey of Livability Policies and Practices - AARP. AARP. Available at: http://www.aarp.org/home-garden/livable-communities/info-11-2011/Aging-In-Place.html. Accessed April 16, 2014.