Abstract

Objective

In 2009 FDA issued a black box warning for varenicline and neuropsychiatric events. We studied efficacy (smoking cessation) of varenicline, and safety (neuropsychiatric events) in both randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and a large observational study. The observational study was included to determine the generalizability of the RCT findings to the general population.

Method

RCTs: Re-analysis of all 17 placebo controlled RCTs (n=8027) of varenicline conducted by Pfizer using complete intent-to-treat person-level longitudinal data.

Observational Study

Analysis of Department of Defense collected adverse neuropsychiatric adverse event data in inpatients and outpatients taking varenicline versus nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) (n=35,800). The primary endpoints for the RCTs were smoking abstinence and adverse event reports of suicidal thoughts and behavior, depression, aggression/agitation, and nausea. The effect of varenicline in patients with (n=1004) and without (n=7023) psychiatric disorders was examined. The primary endpoints for the observational study were anxiety, depression, drug induced mental disorder, episodic and mood disorder, other psychiatric disorder, post traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia, suicide attempt, transient mental disorder.

Results

RCTs: Varenicline did not increase rates of suicidal events, depression, or aggression/agitation. Varenicline increased risk of nausea (OR=3.69, 95% CI = (3.03, 4.48), p<0.0001). Varenicline increased rate of abstinence by 124% compared to placebo (p<0.0001), and 22% compared to bupropion (p<0.0001). While having a current psychiatric disorder or history of psychiatric illness increased the risk of neuropsychiatric events, it did so equally in treated and control patients.

Observational Study

Following propensity score matching, overall rate of neuropsychiatric disorders was lower for varenicline versus NRT (2.28% versus 3.16%, p<0.0001).

Conclusions

In the RCTs, varenicline revealed no increased risk of neuropsychiatric adverse events relative to placebo. Varenicline provided greater benefit in terms of smoking cessation relative to both placebo and bupropion. The same results were observed in patients with and without a current psychiatric disorder or history of psychiatric illness. In the observational study, the overall rate of neuropsychiatric disorders was lower in patients treated with varenicline relative to NRT, revealing that the finding of no increased risk of neuropsychiatric adverse events in RCTs generalizes to the population of patients engaging in treatment with varenicline.

Introduction

Varenicline, a nicotine receptor partial agonist, has received FDA approval for use in smoking cessation. Benefits from varenicline in terms of smoking cessation are generally two to three times greater than unassisted attempts at quitting (1, 2). Post-marketing surveillance evidence that varenicline may be associated with increased risk of neuropsychiatric events, such as depression and suicidal thoughts and behavior, has led to an FDA black box warning (3).

To date, the safety of varenicline with regard to neuropsychiatric events and possible mortality due to suicide has been debated without resolution (4). Reports (5) of higher frequency of spontaneous reports of depression and suicide and related thoughts and behaviors for varenicline, contrast with randomized clinical trials that have not shown evidence of increased risk (2). For example, a pooled analysis of 10 of the Pfizer randomized controlled trials (RCTs), through 2008 (6) found a relative risk of 1.02 (95% CI 0.86-1.22) for incidence of psychiatric disorders (other than sleep disturbance) for varenicline (n=3091) relative to placebo (n=2005). There were no cases of suicidal ideation or behavior. Similarly, Garza (7) studied 110 smokers without a history of psychiatric illness in a placebo controlled RCT of varenicline, and found no effect of varenicline on measures of depression, anxiety, aggression or irritability. In terms of large-scale observational studies, Gunnell (8) examined reports of depression and suicidal thoughts and behavior in patients taking nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), varenicline, and bupropion in a cohort of over 80,000 patients in the UK and found no evidence of an effect of varenicline on these neuropsychiatric events relative to either comparator.

Kasliwal (9) used a physician survey methodology, prescription event monitoring, to study the adverse event profile for varenicline in a cohort of 2,682 patients, and found two cases of attempted suicide during treatment in patients with a history of psychiatric illness. A recent RCT of 294 community volunteers comparing varenicline and bupropion to placebo in terms of prospective neuropsychiatric endpoints found decreased depression, negative affect and sadness for varenicline treated patients relative to placebo (10).

The FDA commissioned the Veterans Administration (VA) and Department of Defense (DoD) to conduct large-scale observational studies to compare the risk of psychiatric hospitalization between patients treated with varenicline and NRT (11). These two parallel studies used propensity score matching (12) to minimize bias related to the differential selection effects for these two treatments. The authors reported that “Neither study found a difference in risk of neuropsychiatric hospitalizations between Chantix and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT; e.g., NicoDerm patches).” The FDA noted the limitation that these studies were restricted to neuropsychiatric events requiring hospitalization. As an example, a suicide attempt that led to treatment limited to the emergency room would not have been included in this analysis. The FDA commented the study was not sufficiently powered to detect rare adverse events. The published paper on the DoD study (13) has more details regarding the study design, analysis and results and reports no increase in neuropsychiatric hospitalization rate on varenicline relative to NRT during the periods of either 30 days or 60 days following a new treatment initiation (13). This study was conducted prior to the first FDA warning to minimize selection effects and stimulated reporting of neuropsychiatric adverse events. The authors note that “Consistent with the primary outcome definition, the rates of specific event types were not increased significantly for the secondary outcome definitions of any in-patient or out-patient diagnoses (data not shown).”

To further study this question of the safety of varenicline in terms of neuropsychiatric events, we obtained all longitudinal efficacy and safety (depression, aggression/agitation, suicidal events, and nausea) patient-level data for the 17 placebo controlled RCTs of varenicline conducted by Pfizer (see Table 1). These studies include two recent RCTs conducted exclusively in patients with a recent history of depression and schizophrenia so that we are able to examine the extent to which having a current psychiatric disorder or history of psychiatric illness impacts the effect of treatment on neuropsychiatric events. Through the Freedom of Information Act, we obtained complete neuropsychiatric event data from the Department of Defense (DoD) study of neuropsychiatric events in 35,800 inpatients and outpatients treated with NRT or varenicline (13). The DoD data allow us to determine the generalizability of the RCT findings to a general population that is not subject to inclusion and exclusion criteria characteristic of RCTs. These data also allow us to present a more detailed presentation of the results of all events (outpatient and inpatient) than were previously reported by the original investigators (13).

Table 1.

Summary of RCTs

| Study | Design | Duration | Treatment Groups | No. of Subj. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase II | ||||

|

A3051046_48

Japan |

R, PG, DB, PC | 12 weeks treatment, plus nontreatment follow-up to Week 52 |

Varenicline 0.25 mg BID Varenicline 0.5 mg BID Varenicline 1 mg BID Placebo |

153 155 156 154 |

|

A3051002

Dose-ranging |

R, PG, DB, PC and active-control |

Varenicline: 6 weeks treatment plus 1 week placebo; Zyban: 7 week treatment follow-up to Week 52 |

Varenicline 0.3 mg QD Varenicline 1 mg QD Varenicline 1 mg BID Zyban 150 mg BID Placebo |

126 126 125 126 123 |

|

A3051016

Flexible dosing (nontreatment follow-up in Study A3051019) |

R, PG, DB, PC | 12 weeks treatment, plus nontreatment follow-up 1o Week 52 |

Varenicline flexible dosing 0.5 lo 2 mg daily Placebo |

157 155 |

|

A3051037

Long-term safety |

R, PG, DR, PC | 52 weeks treatment | Varenicline 1 mg BID Place |

251 126 |

| Phase III | ||||

|

A3051007

titration (nontrentment follow-up in Study A3051018) |

R, PG, DB, PC | 12 weeks treatment, plus nontreatment follow-up to Week 52 |

Varenicline 0.5 mg BID Varenicline 0.5 mg BID Varenicline 1 mg BID Varenicline 1 mg BID Placebo |

124 129 124 129 121 |

|

A3051045

Taiwan and Korea |

R, PG, DB, PC | 12 weeks treatment, Plus nontreatment follow-up to Week 52 |

Varenicline 1 mg BID Placebo |

126 124 |

|

A3051049

CVdisease |

R, PG, DB, PC | 12 weeks treatment, plus nontreatment follow-up to Week 52 |

Varenicline, 1 mg BID: Placebo |

353 350 |

|

A3051054

COPD |

R, PG, DB, PC | 12 weeks treatment plus nontreatment follow-up to Week 52 |

Varenicline, 1 mg BID: Placebo |

248 251 |

|

A3051055

Multinational Asian sites |

R, PG; DB, PC | 12 weeks treatment plus nontreatment follow-up to Week 24 |

Varenicline, 1 mg BID Placebo |

165 168 |

|

A3051028

Zyban comparison |

R, PG, DB, PC and active comparater |

12 weeks treatment, plus noutreatment follow-up to Week 52 |

Varenicline, 1 mg BID Zyban 150 mg BID Placebo |

349 329 344 |

|

A3051036

Zyban comparison |

R, PG, DB, PC and active comparator |

12 weeks treatment, plus nontreatment follow-up to Week 52 |

Varenicline, 1 mg BID Zyban 150 mg BID Plaecbo |

343 340 340 |

| Phase IV | ||||

|

A3051080

Multinational sites in Africa, Mid-East, S. America |

R, PG, DB, PC | 12 weeks treatment, plus nontreatment follow-up 1o Week 24 |

Varenicline, 1 mg BID: Placebo |

390 19S |

|

A3051095

Flexible quit date |

R, PG, DB, PC | 12 weeks treatment, plus nontreatment follow-up to Week 40 |

Varenicline, 1 mg BID: Placebo |

486 165 |

|

A3051104

Smokeless tobacco |

R, PG, DB, PC | 12 weeks treatment, plus nontreatment follow-up to Week 26 |

Varenicline, 1 mg BID: Placebo |

213 218 |

|

A3051115

neuropsychiatric symptoms |

R, PG, DB, PC | 12 weeks treatment, plus 30 day nontreatment follow-up |

Varenicline, 1 mg BID: Placebo |

55 55 |

|

A3051072

Safely and efficacy in patients with Schizophrenia |

R, PG, DB, PC | 12 weeks treatment, plus 12 weeks nontreatment follow-up |

Varenicline, 1 mg BID: Placebo |

84 43 |

|

A3051122

Safely and efficacy in patients with Depression |

R, PG, DB, PC | 12 week treatment, Plus nontreatment follow-np to Week 52 |

Varenicline, 1 mg BID: Placebo |

256 269 |

Methods

Study Data

RCTs: A detailed description of the study data is provided in Table 1. There were 4823 varenicline subjects, 795 bupropion subjects and 3204 placebo subjects across the 17 studies for a total of 81,105 weekly measurement occasions during active treatment. Average treatment duration was 11.6 weeks. 1004 patients had a current psychiatric disorder (studies 1072 and 1122) or past psychiatric illness (a subset of patients in the other 15 studies) including depression, schizophrenia, psychosis, panic disorder, anxiety disorder, mood disorder and personality disorder. We examined both the outcome of suicidal thoughts and behavior that formed the basis for the black box warning, as well as their possible causal factors of depression, aggression, agitation and mood lability, and the unrelated side effect, nausea as a positive control. Our measure of depression was the high-level MedDRA safety group term Depressed Mood Disorders and Disturbances (DMDD) consisting of agitated depression, anhedonia, depressed mood, depression, depressive symptom, dysthymic disorder, feeling of despair, and major depression. Aggression/agitation was defined as the combination of lower-level MedDRA terms aggression, aggressive, aggressiveness, aggressivity, aggressivity signs, agitation, emotional lability, feelings of aggression, hostility, increased agitation, labile emotions, labile mood, labile moods, observed aggressiveness, and violent behavior. Suicidal events were defined as suicidal thoughts and behavior. Nausea included all lower level MedDRA terms that included the word nausea.

Observational Study

As described by both the FDA (11) and the original investigators (13), the DoD study was a retrospective cohort study comparing acute (30 day and 60 day) rates of neuropsychiatric adverse events from the Military Health System. The time-frame (August 1, 2006 to August 31, 2007) was prior to FDA warnings to minimize selection effects and stimulated reporting due to the extensive media coverage of these warnings. There were 19,933 patients treated with varenicline and 15,867 patients treated with NRT. The data were restricted to new users defined by not receiving treatment with either varenicline or NRT for the prior 180 days. Following the original study (13), we examined the following neuropsychiatric diagnoses: “anxiety disorder, depressive disorder, drug-induced mental disorders, transient mental disorders, schizophrenia, episodic and mood disorders, delusional disorders, other psychiatric disorder, anxiety disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and suicide attempt.” Data were analyzed both including and excluding patients with a current psychiatric disorder or history of psychiatric illness.

Statistical Methods

RCTs: Efficacy data were analyzed using a 3-level mixed-effects logistic regression model (14). Week was expressed as loge(week) to accommodate nonlinearity in the temporal response patterns. The treatment by time interaction, describes the effect of treatment on the rate of smoking over time. Comparisons were made to both placebo and bupropion. For AE rates (DMDD, suicide, aggression, nausea), data were collapsed over time and AE rates were compared between varenicline and placebo (bupropion was not included) using a 2-level mixed-effects logistic regression with random intercept and treatment effects. Nausea was included as a positive control, since varenicline has been documented to produce nausea. Both an overall analysis and an analysis examining the treatment by psychiatric illness interaction were performed. A second analysis compared DMDD rates following treatment discontinuation. Analyses were conducted using SuperMix (15).

Observational Study

Unadjusted rates of neuropsychiatric disorders were compared between varenicline and NRT using Fisher’s exact test. Propensity score matching was used to create a 1:1 matched set of varenicline and NRT treated patients in terms of demographic characteristics, and historical (past year) comorbid physical illness and psychiatric illnesses, and psychiatric and smoking cessation medications (see Table 2). Rates were compared using generalized estimating equations (16).

Table 2.

Frequency Distributions for Variables used in Propensity Score Matching U.S. Department of Defense Observational Study

| Before Matching |

After PS Matching |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Varenicline N=19933 |

Nicotine Patch N = 15867 |

Varenicline N=13215 |

Nicotine Patch N=13215 |

| N (%) / Mean (SD) | N (%) / Mean (SD) | N (%) / Mean (SD) | N (%) / Mean (SD) | |

| Age | 42.1 (14.3) | 35.1 (12.6) | 36.8 (12.4) | 36.8 (12.8) |

| Charlson comorbidity score | 0.37 (0.97) | 0.21 (0.77) | 0.23 (0.76) | 0.24 (0.83) |

| Inpatient admission | 2054 (10.30) | 1756 (11.07) | 1377 (10.42) | 1408 (10.65) |

| Diagnoses in previous year | ||||

| Anxiety | 1054 (5.29) | 692 (4.36) | 594 (4.49) | 619 (4.68) |

| Chronic pain | 78 (0.39) | 36 (0.23) | 29 (0.22) | 35 (0.26) |

| Delusional disorder | 3 (0.02) | 5 (0.03) | 3 (0.02) | 4 (0.03) |

| Depressive disorder | 1097 (5.50) | 694 (4.37) | 592 (4.48) | 630 (4.77) |

| Drug-induced mental disorder | 45 (0.23) | 42 (0.26) | 31 (0.23) | 33 (0.25) |

| Episodic and mood disorder | 879 (4.41) | 595 (3.75) | 510 (3.86) | 529 (4.00) |

| Other nonorganic psychosis | 34 (0.17) | 25 (0.16) | 16 (0.12) | 20 (0.15) |

| Personality disorder | 101 (0.51) | 121 (0.76) | 76 (0.58) | 83 (0.63) |

| PTSD | 247 (1.24) | 237 (1.49) | 164 (1.24) | 173 (1.31) |

| Schizophrenia | 41 (0.21) | 30 (0.19) | 25 (0.19) | 25 (0.19) |

| Substance abuse | 280 (1.40) | 382 (2.41) | 225 (1.70) | 240 (1.82) |

| Suicide attempt | 14 (0.07) | 21 (0.13) | 13 (0.10) | 14 (0.11) |

| Transient mental disorder | 48 (0.24) | 38 (0.24) | 30 (0.23) | 32 (0.24) |

| Neuropsychiatric (all above) | 2595 (13.02) | 1762 (11.10) | 1477 (11.18) | 1539 (11.65) |

| Filled prescriptions in previous year | ||||

| Any Antipsychotic medication | 560 (2.81) | 451 (2.84) | 343 (2.60) | 371 (2.81) |

| Bupropion | 2074 (10.40) | 2301 (14.50) | 1419 (10.74) | 1507 (11.40) |

| Pain medication | 14149 (70.98) | 10905 (68.73) | 9190 (69.54) | 9170 (69.39) |

| Any Psychiatric medication | 7629 (38.27) | 5260 (35.42) | 4403 (33.32) | 4567 (34.56) |

| Sleep medication | 2263 (11.35) | 1345 (8.48) | 1174 (8.88) | 1220 (9.23) |

| Other smoking cessation medication | 424 (2.13) | 1061 (6.69) | 415 (3.14) | 434 (3.28) |

| SSRIs | 2964 (14.87) | 1759 (11.09) | 1521 (11.51) | 1593 (12.05) |

| TCAs | 849 (4.26) | 502 (3.16) | 419 (3.17) | 463 (3.50) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 10746 (53.91) | 8831 (55.66) | 7586 (57.40) | 7689 (58.18) |

| Other | 9187 (46.09) | 7036 (44.34) | 5629 (43.60) | 5526 (41.82) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 10071 (50.52) | 9388 (59.17) | 7738 (58.55) | 7723 (58.44) |

| Other | 9862 (49.48) | 6479 (40.83) | 5477 (41.45) | 5492 (41.56) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 8763 (43.96) | 5094 (32.11) | 4814 (36.43) | 4737 (35.85) |

| Male | 11168 (56.04) | 10770 (67.89) | 8399 (63.57) | 8476 (64.15) |

Results

RCTs

Suicidal Thoughts and Behavior

The overall effect of varenicline treatment was not significant (OR=0.57, 95% CI=0.23, 1.38). Psychiatric illness did not moderate the effect of varenicline treatment (p=0.39). The rates of suicidal thoughts and behavior in patients without a current psychiatric disorder or history of psychiatric illness were 1.46 per 1000 control patients versus 0.47 per 1000 treated patients. The rates of suicidal thoughts and behavior in patients with a current psychiatric disorder or history of psychiatric illness were 15.39 per 1000 control patients versus 14.57 per 1000 in varenicline treated patients. There were no suicides.

Depression

The overall effect of varenicline treatment was not significant (OR=1.01, 95% CI=0.68, 1.52). Psychiatric illness did not moderate the effect of varenicline treatment (p=0.36). The rates of DMDD in patients without a current psychiatric disorder or history of psychiatric illness were 20.02 per 1000 control patients versus 22.70 per 1000 in varenicline treated patients. The rates of DMDD in patients with a current psychiatric disorder or history of psychiatric illness were 81.32 per 1000 control patients versus 80.15 per 1000 in varenicline treated patients. No effect of varenicline treatment on DMDD events was observed following treatment discontinuation (OR=0.76, 95% CI=0.21, 2.72), 3.45 per 1000 for placebo versus 3.08 per 1000 for varenicline.

Aggression/agitation

The overall effect of varenicline treatment was not significant (OR=1.27, 95% CI=0.85, 1.92). Psychiatric illness did not moderate the effect of varenicline treatment (p=0.64). The rates of aggression/agitation in patients without a current psychiatric disorder or history of psychiatric illness were 6.91 per 1000 control patients versus 9.83 per 1000 in varenicline treated patients. The rates of aggression/agitation in patients with a current psychiatric disorder or history of psychiatric illness were 46.15 per 1000 control patients versus 51.00 per 1000 in varenicline treated patients.

Nausea

The overall effect of varenicline treatment was significant (OR=3.69, 95% CI=3.03, 4.48). Psychiatric illness did not moderate the effect of varenicline treatment (p=0.89). The rates of nausea in patients without a current psychiatric disorder or history of psychiatric illness were 92.80 per 1000 control patients versus 275.45 per 1000 in varenicline treated patients. The rates of nausea in patients with a current psychiatric disorder or history of psychiatric illness were 109.89 per 1000 control patients versus 315.12 per 1000 in varenicline treated patients.

Efficacy

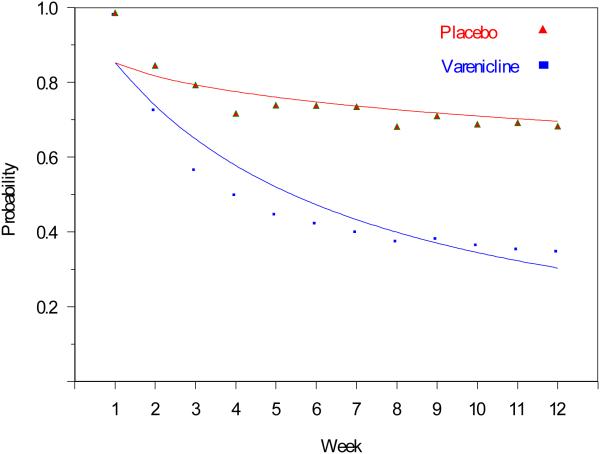

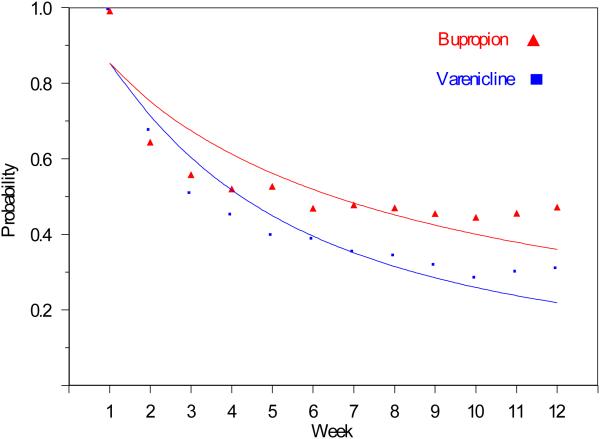

moking abstinence was significantly increased in varenicline relative to both placebo (p<0.0001) and bupropion (p<0.0001). After 12 weeks, the estimated probability of abstinence was 30% for placebo and 68% for varenicline (RR=2.24, 95% CI (2.21, 2.27), see Figure 1. There was no evidence of a treatment by psychiatric illness interaction (p=0.98), indicating that varenicline is comparably effective in patients with and without a current psychiatric disorder or history of psychiatric illness. In the three studies that included bupropion, the probability of abstinence at 12 weeks was greater on varenicline (78%) compared with bupropion (64%) [RR=1.22, 95% CI (1.16, 1.29)], see Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Observed and Estimated probabilities of smoking

Figure 2.

Observed and Estimated Probabilities of Smoking

Observational Study

The unadjusted overall rates of neuropsychiatric adverse events were 2.38% for varenicline and 3.17% for NRT (p<0.0001). Following propensity score matching, the rates were 2.28% for varenicline and 3.16% for NRT (OR=0.72, 95% CI (0.62, 0.83), p<0.0001). Decreases in drug induced mental disorders (OR=0.10, 95% CI (0.04, 0.24), p<0.0001), and other psychiatric disorders (OR=0.20, 95% CI (0.04, 0.91), p<0.04) were also found (see Table 3). The only disorder more frequently observed in varenicline treated patients was transient mental disorder; however, there were few such events (9 cases for varenicline 0.05% versus 4 cases for NRT 0.03%), and the results were not statistically significant (0.06% for varenicline versus 0.02% for NRT following propensity score matching). In general, the results with and without propensity score matching were quite similar. When patients with a neuropsychiatric event (i.e., disorder or suicide attempt) in the previous year were excluded, results were also quite similar. The unadjusted overall rates of neuropsychiatric adverse events were 0.53% for varenicline and 1.13% for NRT (p<0.0001). Following propensity score matching, the rates were 0.52% for varenicline and 1.09% for NRT (OR=0.47, 95% CI (0.35, 0.65), p<0.0001).

Table 3.

Neuropsychiatric Events Before and After Propensity Score Matching U.S. Department of Defense Observational Study

| Before PS Matching |

After PS Matching |

Odds Ratios and Confidence Intervals |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Varenicline (N = 19,933) Patients with Event N (%) |

Nicotine Patch (N = 15,867) Patients with Event N (%) |

P-Value Fisher's Exact |

Varenicline (N = 13,215) Patients with Event N (%) |

Nicotine Patch (N = 13,215) Patients with Event N (%) |

P-Value McNemar's Exact |

Odds Ratios |

Confidence Intervals |

| Anxiety Disorder | 151 (0.76%) | 132 (0.83%) | 0.44 | 92 (0.70%) | 110 (0.83%) | 0.23 | 0.84 | 0.63-1.10 |

| Depressive Disorder | 113 (0.57%) | 108 (0.68%) | 0.18 | 71 (0.54%) | 92 (0.70%) | 0.12 | 0.77 | 0.57-1.05 |

| Drug Induced Mental Disorder |

7 (0.04%) | 70 (0.44%) | < 0.0001 | 6 (0.05%) | 59 (0.45%) | < 0.0001 | 0.10 | 0.04-0.24 |

| Episodic and Mood Disorder |

190 (0.95%) | 152 (0.96%) | 0.99 | 118 (0.89%) | 128 (0.97%) | 0.56 | 0.92 | 0.72-1.18 |

| Otiier Psychiatric Disorder |

3 (0.02%) | 10 (0.06%) | 0.02 | 2 (0.02%) | 10 (0.08%) | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.04-0.91 |

| Post Traumatic Stress Disorder |

64 (0.32%) | 86 (0.54%) | 0.002 | 45 (0.34%) | 65 (0.49%) | 0.07 | 0.69 | 0.47-1.01 |

| Schizoplirenia | 10 (0.05%) | 15 (0.09%) | 0.16 | 9 (0.07%) | 12 (0.09%) | 0.66 | 0.75 | 0.32-1.78 |

| Suicide Attempt | 2 (0.01%) | 4 (0.03%) | 0.42 | 2 (0.02%) | 3 (0.02%) | 0.99 | 0.67 | 0.11-3.99 |

| Transient Mental Disorder |

9 (0.05%) | 4 (0.03%) | 0.41 | 8 (0.06%) | 3 (0.02%) | 0.23 | 2.67 | 0.71-10.06 |

| Neuropsychiatric Disorders (All Above) |

475 (2.38%) | 503 (3.17%) | < 0.0001 | 301 (2.28%) | 417 (3.16%) | < 0.0001 | 0.72 | 0.62-0.83 |

Discussion

Analysis of longitudinal neuropsychiatric event data across the 17 placebo controlled double-blind RCTs of varenicline revealed no evidence of increased risk of suicidal ideation or behavior or neuropsychiatric events (depression, aggression and agitation potentially associated with greater risk of suicidal behavior) on varenicline. Moreover, we did not detect increased risk of depression related events following treatment discontinuation. There is, however, clear evidence that varenicline does cause side effects such as nausea, illustrating our ability to detect AEs when present. A further strength of our research synthesis of the RCT data is that we included two new studies conducted in patients with current diagnoses of depression and schizophrenia and identified additional subjects from the other studies with a history of psychiatric illness. In total, 13% of the sample had a current psychiatric disorder or history of psychiatric illness, allowing us to determine the extent to which having a current psychiatric disorder or history of psychiatric illness moderated the effect of the drug on both efficacy and safety. No evidence of a moderator effect was found, indicating that patients with psychiatric illness (current or historically) are not at increased risk of developing neuropsychiatric events when treated with varenicline.

In terms of efficacy, 12 weeks of treatment with varenicline produced a 124% increase in the rate of abstinence relative to placebo and 22% relative to bupropion. The number needed to treat (NNT) based on the estimated abstinence rates at 12 weeks was 2.63, i.e., for slightly less than every 3 patients treated, one additional patient will be abstinent on varenicline relative to placebo. A similar conclusion was reached by the recent Cochrane collaboration review of nicotine receptor partial agonists for smoking cessation (2). They found that the chances of successful long-term smoking cessation was between two- and three-fold better for varenicline compared with pharmacologically unassisted smoking cessation attempts and that the main adverse event was nausea at mild to moderate levels which tended to subside over time. With respect to neuropsychiatric events, they concluded that: “There is little evidence from controlled studies of any link between varenicline and psychiatric adverse events.” We reach the same conclusion based on a more complete analysis of the data. The DoD data showed that eight of the 9 neuropsychiatric event types examined were less frequent in patients taking varenicline versus NRT. The only disorder more frequently observed in varenicline treated patients was transient mental disorder; however, there were few of these events (9 cases for varenicline 0.05% versus 4 cases for NRT 0.03%), and the apparent difference was not statistically significant. Similar results were obtained when patients with psychiatric illness (past year) were included or excluded. These results are similar to recent FDA (12) and DoD (13) reports regarding the absence of risk for psychiatric hospitalizations in VA and DoD patients treated with varenicline relative to NRT. We note that the original DoD investigators (13) focused on inpatient events because outpatient events “are more likely to suffer from misclassification and should be interpreted with caution” and that “In out-patient settings, codes may represent instances of routine psychiatric care rather than adverse neuropsychiatric events.” While we agree that the absence of an effect seen for neuropsychiatric hospitalizations is a critically important finding and stands on its own, our analysis of the combination of in-patient and out-patient events adds further to the finding by ruling out potential criticisms that important events such as suicide attempts that did not lead to hospitalization would be overlooked in such an analysis. Furthermore, we do not see why the concern that outpatient treatment may be for a psychiatric illness unrelated to the medication should not apply equally to hospitalization, and strongly believe that the outpatient reports of neuropsychiatric events provide comparably meaningful and useful data, with the advantage of greatly expanding the sample size and number of outcome events.

It is possible that the decreased risk of neuropsychiatric events seen in the outpatient data for varenicline relative to NRT could be due to patients at higher risk of such events being given NRT instead of varenicline. This explanation is tempered by the fact that the DoD data were for the period prior to the FDA warning.

The other large scale observational study conducted by Gunnell (8), also failed to identify any significant difference between varenicline and NRT in terms of depression and suicidal event rates. These observational studies are important because they demonstrate that the results of the RCTs generalize to the clinical population of patients treated with smoking cessation products and are not limited by the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the specific RCTs.

Signals have been identified, however, in spontaneous reports of depression and suicidal events made to the FDA’s AERS/MedWatch system. As previously noted, a possible safety signal for varenicline (relative to bupropion and NRT) has been reported (5) for depression and suicidal events. As noted by Cahill (2), however, the limitations of this class of data include “confounding by indication, under-reporting, double-counting from multiple sources and lack of representativeness which limits generalizability (Gibbons 2011)” (4). They also note that because of heightened media coverage and FDA warnings, neuropsychiatric events may be more likely to be reported to FDA for varenicline than for NRT. The FDA (17) also cautioned against drawing causal inferences from such data noting that there is often insufficient information on the report forms to evaluate the event, and that not all adverse events are reported to them; hence they “cannot be used to calculate the incidence of an adverse event in the U.S. population.”

In an effort to shed further light on this question, we obtained the same FDA data analyzed by Moore (5) and followed their methodology for including and excluding AE reports. We were able to obtain reasonably similar total number of events for varenicline, 10,291 versus 9,575 reported by Moore and colleagues for the time-period of 1998-2010 included in their analysis. Note that this time-frame includes 8 years prior to varenicline’s entry into the market and extends through the period of media attention and FDA warnings. In our analysis, we restricted the time frame to the period during which varenicline was on the market and prior to the media attention and FDA warnings that could have stimulated reporting (2nd quarter 2006 through 3rd quarter 2007). We found no evidence of a safety signal for varenicline relative to NRT during this period of time for suicidal events (OR=0.69, 95% CI=0.40, 1.26), an effect for depression events (OR=1.72, 95% CI=1.08, 2.84), and no effect for aggression events (OR=0.58, 95% CI=0.27, 1.37). By contrast, much greater magnitude, significant effects for bupropion versus NRT were observed during this same time period (suicidal events (OR=6.85, 95% CI=3.18, 14.77), depression events (OR=5.17, 95% CI=2.44, 10.82), and aggression events (OR=7.64, 95% CI=2.90, 20.58). Given the limitations of these data, their interpretation remains difficult; however, these results at least offer the alternative explanation that safety signals identified for varenicline related to neuropsychiatric events may have been produced by stimulated reporting.

In summary, our research synthesis that included re-analysis of all sponsor conducted placebo controlled RCTs and an original analysis of a large DoD observational dataset, revealed no evidence that varenicline is associated with adverse neuropsychiatric events while confirming nausea as side effect. These findings are generally consistent with the literature and other RCTs and large observational studies. Our analysis reveals evidence in support of the superior efficacy of varenicline relative to both placebo and bupropion; therefore indicating considerable benefit without evidence of risk of serious neuropsychiatric adverse events. These findings generalize to patients with and without recent history of a psychiatric disorder.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements: This work was supported by NIMH grants MH062185 (JJM) and MH8012201 (RDG). Dr. Gibbons has served as an expert witness for Pfizer Inc. in a case related to varenicline and neuropsychiatric adverse events. Dr. Gibbons has also served as an expert witness on cases related to antidepressants and suicide for the US Department of Justice and Wyeth Inc. and cases related to gabapentin and suicide for Pfizer Inc. Dr. Mann has received past research support from Glaxo Smith Kline and Novartis for unrelated imaging studies, and receives royalties for the C-SSRS from the Foundation for Mental Health. Data were supplied by Pfizer. Pfizer had no involvement in the analysis of these data, or the writing of the paper. Pfizer reviewed the final manuscript to insure accuracy of the study descriptions and ensure against inadvertent disclosure of confidential information or unprotected inventions. Pfizer did not provide any comments except minor corrections in Table 1. Drs. Gibbons and Mann had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Cahill K, Stead L, Lancaster T. A preliminary benefit-risk assessment of varenicline in smoking cessation. Drug Saf. 2009;32:32–119. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200932020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cahill K, Stead LF, Lancaster T. Nicotine receptor partial agonists for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Apr 18;4:CD006103. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006103.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/DrugSafetyInformationforHeathcareProfessionals/ucm169986.htm. Accessed on 4/3/2013.

- 4.Gibbons RD, Mann JJ. Strategies for quantifying the relationship between medications and suicidal behavior: what has been learned? Drug Safety. 2011;34:375–395. doi: 10.2165/11589350-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore TJ, Furberg CD, Glenmullen J, Maltsberger JT, Singh S. Suicidal behavior and depression in smoking cessation treatments. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tonstad S, Davies S, Flammer M, Russ C, Hughes J. Psychiatric adverse events in Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trials of Varenicline: a Pooled Analysis. Drug Safety. 2010;33:289–301. doi: 10.2165/11319180-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garza D, Murphy M, Tseng LJ, Riordan HJ, Chatterjee A. A Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Pilot Study of Neuropsychiatric Adverse Events in Abstinent Smokers Treated with Varenicline or Placebo. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69(11):1075–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gunnell D, Irvine D, Wise L, et al. Varenicline and suicidal behavior: a cohort study based on data from the General Practice Research Database. BMJ. 2009;339:b3805. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kasliwal R, Wilton LV, Shakir SAW. Safety and drug utilization profile of varenicline as used in general practice in England. Drug Saf. 2009;32:32–499. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200932060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cinciripini PM, Robinson JD, Karam-Hage M, Minnix JA, Lam C, Versace F, Brown VL, Engelmann JM, Wetter D. Effects of varenicline and bupropion sustained-release use plus intensive smoking cessation counseling on prolonged abstinence from smoking and on depression, negative affect, and other symptoms of nicotine withdrawl. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013 Mar 27; doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.678. e-pub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm276737.htm. Accessed on 4/3/2013.

- 12.Rosenbaum P, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 198370:41–50. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer TE, Taylor LG, Xie S, Graham DJ, Mosholder AD, Williams JR, Money D, Quellet-Hellstrom RP, Coster TS. Neuropsychiatric events in varenicline and nicotine replacement patch users in the military health system. Addiction. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04024.x. epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hedeker D, Gibbons RD. Longitudinal Data Analysis. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hedeker D, Gibbons RD, Du Toit SHC, Patterson D. SuperMix - A program for mixed-effects regression models. Scientific Software International; Chicago: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Food and Drug Administration Adverse Events Reporting System (AERS) 2012 Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Surveillance/AdverseDrugEffects/default.htm. Accessed on 4/3/2013.