Abstract

Background

Clinical practice guidelines should aim to assist clinicians in making evidence-based choices in the care of their patients. This review attempts to determine the extent of evidence-based support for clinical practice guideline recommendations concerning cutaneous melanoma follow up and to evaluate the methodological quality of these guidelines.

Methods

Current guidelines providing graded recommendations regarding patient follow up were identified through a systematic literature review. The authors reviewed the evidence base used to formulate recommendations in each of the guidelines and appraised the quality of the guidelines using the AGREE II (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation) instrument.

Results

Most guideline recommendations concerning the frequency of routine skin examinations by a clinician and the use of imaging and diagnostic tests in the follow up of melanoma patients were based on low-level evidence or consensus expert opinion. Melanoma follow-up guidelines are of variable methodological quality, with some guidelines not recommended by the appraisers for use in clinical practice.

Conclusion

Clinicians should be aware of how scant the evidence base is for many recommended courses of action. As a consequence of the paucity of evidence in the field of melanoma follow up, there is considerable variability in the guidance provided. The variable methodological quality of guidelines for melanoma follow up could be improved by attention to the criteria described in AGREE II.

Review criteria

A search of 11 electronic databases and websites was conducted to identify potentially relevant guidelines published in 2006 or later, in addition to use of a review article by Speijers et al.

Relevant guidelines were selected based on PIPOH criteria, which were delineated prior to collating the literature.

Authors identified the evidence supporting follow-up recommendations in each guideline.

Authors appraised guideline quality using AGREE II.

Message for the clinic

Melanoma follow-up recommendations concerning frequency of physical examinations, duration of follow-up appointments and use of imaging or diagnostic tests are based mostly on low-level evidence or consensus expert opinion. The level of uncertainty associated with these recommendations is often not apparent from the way the guideline is presented for the development.

Clinicians should further investigate the metho-dology and evidence supporting melanoma follow-up recommendations before applying them in the clinical setting.

Background

Australia and New Zealand have the highest incidence of melanoma in the world, with an age-standardised incidence in Australia of 48.8 per 100,000 in 2008, meaning that the average person has a 1 in 18 risk of being diagnosed with the disease before age 85 1,2. Data from the 2008 American Joint Committee on Cancer Melanoma Staging Database show that 10-year survival rates range from 93% for stage IA to 39% for stage IIC 3. In Australia, melanoma patients had the third highest 5-year survival rates of all cancers at 92% from 1998 to 2004 4. Consequently, in Australia and other developed nations, there is a growing pool of melanoma survivors who will require follow up for disease recurrence. Evidence-based guidance is needed on how often and what type of follow up is required for these patients. Patient follow up is characterised by appointments where physical examinations and/or diagnostic tests are performed in accordance with a prescribed schedule. Follow up serves a number of purposes: to facilitate the early detection of recurrent tumours and to enable swift action to be taken if a recurrence is detected 5, to reassure patients, to provide a vehicle for continuing education regarding skin self-assessment, for management of treatment-related side effects and an opportunity to provide psychosocial support 6.

Guidelines may be described as ‘systematically developed statements to assist practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate healthcare for specific clinical circumstances’ 7. Guideline recommendations may be based on either scientific evidence or the expertise of the guideline developers via a consensus decision-making process. Central to the development of evidence-based guidelines, as opposed to consensus-based guidelines, is a critique of the quality and strength of evidence supporting recommended courses of action and the selection of the best available evidence through a rigorous systematic review of the available literature 8.

Guideline recommendations vary between countries or agencies of origin, and this is often thought to be because of the need to ‘localise’ the available international evidence so that it is relevant to clinical practice within the targeted health system and target population. However, a recent comparison of seven guidelines for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder has noted that differences between guidelines are often because of insufficient empirical data to drive the recommendations 9. When research evidence is limited, transparency and rigour in guideline development are imperative to assist the interpretation of guideline recommendations. The Guidelines International Network (GIN), formed in Paris in 2002 10, seeks to improve the quality of guideline development and reduce inappropriate variation through the establishment and promotion of high-quality standards of guideline development 10. In 2003, the AGREE (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation) collaboration published well-defined methodological criteria for guideline development 11 which were updated (AGREE II) in 2010 8. Nevertheless, two reviews of clinical practice guidelines, published in 2007 and 2009, dealing with prevention of cardiovascular disease and prostate cancer follow up, respectively, found that guidelines were mostly of poor methodological quality and lacked transparency 12,13. Given the increasing need for guidance on the clinical follow up of melanoma survivors, it would be helpful to know whether the available ‘evidence-based’ guidelines can be trusted. This study aims to determine whether clinical practice guidelines on the follow up of patients diagnosed with cutaneous melanoma are evidence based; evaluate whether the processes used to develop these guidelines were rigorous and transparent; and ascertain whether practice recommendations are consistent across the guidelines.

Methods

Selection of cutaneous melanoma follow-up guidelines

A search of 11 electronic databases and websites was conducted in February 2013 to identify potentially relevant guidelines: EMBASE; PubMed (Medline); Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Guidelines Portal; National Guidelines Clearinghouse (NGC); GIN Library; Ontario Guideline Advisory Committee (GAC); Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health (CADTH); National Health Services (NHS) Guidelines Finder; Royal College of Physicians (RCP) Guideline Database; National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE); New Zealand Guidelines Group (NZGG) and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). In addition, a recent review article by Speijers et al. 14 citing 19 mostly European melanoma follow-up guidelines (15 of which were published in 2006 or later) was used to source guidelines that might not have been indexed in the standard databases.

The database search was not specific for follow up, instead aiming to retrieve all guidelines specific to skin cancer, to capture more general guidelines which include a description of melanoma follow up. Terms used in the search were melanoma, skin, cutaneous, dermal, cancer, neoplasm and tumour. Guidelines published, revised or reaffirmed during the period from 2006 to February 2013 were included. Only one clinical practice guideline per independent organisation, i.e. the most recently published full guideline, was selected.

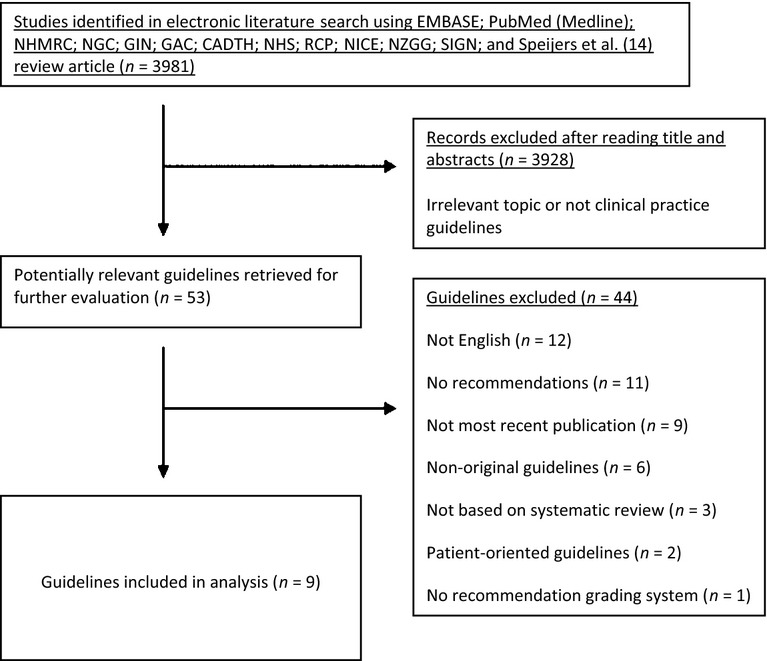

The study selection process (Figure1) applied PIPOH 15 selection criteria. To reduce bias, these criteria were delineated prior to collating the literature and included: patient population (people with suspected or proven diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma), intervention (follow up of melanoma patients), professionals or target audience of the guideline (general practitioners, oncologists, dermatologists, surgeons, physicians or other referred specialists) and healthcare setting (primary, secondary or tertiary). In addition, guidelines were excluded if they: had only recommendations that were developed solely on the basis of consensus; were summaries of another guideline; were not in English (or translated into English); had no explicit grading system for determining the strength of recommendations; had no melanoma follow-up recommendations; referred to another guideline for all melanoma follow-up recommendations; were not based on a systematic literature review; were replaced by a more recent version of the guideline or had expired (past the stated due date for updating).

Figure 1.

Diagram of guideline selection

Initial guideline eligibility on the basis of the collated guidelines was conservatively determined by two authors. When consensus could not be reached, another two reviewers independently assessed the guideline in question and the majority decision prevailed. Melanoma follow-up recommendations were extracted from each guideline and compared, and the evidence cited as supporting each recommendation was also extracted.

Evaluation of guidelines

The AGREE II instrument provided a framework to assess the comparative quality of the different guidelines 8. This tool was used by the four authors to independently assess each guideline. The authors provided a range of experience in guideline development and evaluation, with perspectives including an experienced guideline developer and methodologist, a clinician, a public health academic and a research assistant.

The AGREE II instrument is comprised of 23 items under six domains: scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigour of development, clarity of presentation, applicability and editorial independence (see Table1 for descriptions of each item). Each item is given a rating by assessors from 1 to 7, with 1 indicating ‘strongly disagree’ and 7 indicating ‘strongly agree’ 8.

Table 1.

AGREE II instrument domains and items

| Domain | Item | |

|---|---|---|

| Scope and purpose | 1 | The overall objective(s) of the guideline is (are) specifically described |

| 2 | The health question(s) covered by the guideline is (are) specifically described | |

| 3 | The population (patients, public, etc.) to whom the guideline is meant to apply is specifically described | |

| Stakeholder involvement | 4 | The guideline development group includes individuals from all relevant professional groups |

| 5 | The views and preferences of the target population (patients, public, etc.) have been sought | |

| 6 | The target users of the guideline are clearly defined | |

| Rigour of development | 7 | Systematic methods were used to search for evidence |

| 8 | The criteria for selecting the evidence are clearly described | |

| 9 | The strengths and limitations of the body of evidence are clearly described | |

| 10 | The methods for formulating the recommendations are clearly described | |

| 11 | The health benefits, side effects and risks have been considered in formulating the recommendations | |

| 12 | There is an explicit link between the recommendations and the supporting evidence | |

| 13 | The guideline has been externally reviewed by experts prior to its publication | |

| 14 | A procedure for updating the guideline is provided | |

| Clarity of presentation | 15 | The recommendations are specific and unambiguous |

| 16 | The different options for management of the condition or health issue are clearly presented | |

| 17 | Key recommendations are easily identifiable | |

| Applicability | 18 | The guideline describes facilitators and barriers to its application |

| 19 | The guideline provides advice and/or tools on how the recommendations can be put into practice | |

| 20 | The potential resource implications of applying the recommendations have been considered | |

| 21 | The guideline presents monitoring and/or auditing criteria | |

| Editorial independence | 22 | The views of the funding body have not influenced the content of the guideline |

| 23 | Competing interests of guideline development group members have been recorded and addressed | |

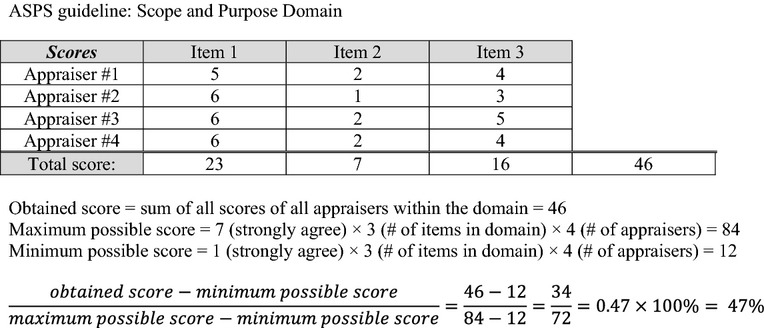

In accordance with AGREE II methodology, mean domain scores were calculated by summing up all the scores of the individual items in a domain and by scaling the total as a percentage of the maximum possible score for that domain across all the four reviewers (see Figure2) 8. The six domain scores are independent and are not intended to be aggregated into a single overall quality score; rather, appraisers give a separate overall score of 1–7 and are asked whether they would recommend the guideline for use 8. An average overall score for each guideline was calculated using the overall scores of the four reviewers.

Figure 2.

Example calculation of an AGREE II domain score

Results

The guideline selection process is represented diagrammatically in Figure1. A total of 3981 records were retrieved in the initial literature search, although the vast majority of these were excluded after screening of title and abstract because they were unrelated to melanoma, skin cancer or cancer screening/surveillance or not clinical practice guidelines. Subsequently, the remaining 53 guidelines were evaluated, and following the application of PIPOH criteria and use of the consensus process, 44 guidelines were excluded. Reasons for exclusion included guidelines not in English (n = 12); guidelines with no recommendations (n = 11); guidelines were not the most recent publication (n = 9); non-original guidelines (n = 6); not based on systematic review (n = 3); patient-oriented guidelines (n = 2) and no recommendation grading system (n = 1).

The included guidelines (n = 9) are listed in Table2. Included guidelines were published by organisations from the United States (n = 4); Australia and New Zealand (n = 1); Scotland (n = 1); the United Kingdom (n = 1); Switzerland (n = 1) and Europe (n = 1).

Table 2.

Guidelines included in analysis of follow-up recommendations

| Guideline title | Organisation | Scope | Year, Countries |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Melanoma in Australia and New Zealand | Cancer Council Australia; Australian Cancer Network; Ministry of Health, New Zealand (CCA) | Cutaneous melanoma | 2008, Australia and New Zealand |

| Cutaneous melanoma. A National Clinical Guideline | Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) | Cutaneous melanoma | 2003 (updated 2004, reaffirmed 2007, 2011), Scotland |

| Revised UK Guidelines for the Management of Cutaneous Melanoma 2010 | British Association of Dermatologists (BAD) | Cutaneous melanoma | 2010, UK |

| Evidence-based Clinical Practice Guideline: Treatment of Cutaneous Melanoma | American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) | Cutaneous melanoma | 2007, USA |

| Long-term Follow-up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers | Children's Oncology Group (COG) | General health and common adult onset cancers | 2006 (updated 2008), USA |

| Guidelines of Care for the Management of Primary Cutaneous Melanoma | American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) | Cutaneous melanoma | 2011, USA |

| Cutaneous Melanoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow up | European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) | Cutaneous melanoma | 2012, Europe |

| Updated Swiss Guidelines for the Treatment and Follow up of Cutaneous Melanoma | Project Group Melanoma of the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK) | Cutaneous melanoma | 2011, Switzerland |

| Melanoma | National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) | Cutaneous melanoma | 2012, USA |

Melanoma follow-up recommendations

Recommendations for the follow up of cutaneous melanoma from each guideline were compiled for comparing the evidence base used by each guideline and to determine the consistency of the guidance that was formulated. All guidelines dealt with the self-examination and education aspect of follow up and all guidelines made at least one recommendation regarding frequency and duration of follow up. All guidelines except COG 16 made recommendations concerning the imaging/diagnostic test components of melanoma follow up.

Self-examination and education

All guidelines agreed that patients should be taught skin self-examination as this was the method by which recurrences were most commonly detected 16–24. In addition, educating family members about self-examination was recommended by ASPS 18. Education about sun-smart behaviour at routine visits was recommended by CCA 19, ESMO 22, SAKK 23 and NCCN 21. The recommendation, found in all the guidelines, that patients should be educated in self-examination to support early detection, is based primarily on consensus and/or clinical experience. To support this recommendation, each of the guidelines used evidence which was different from that used in any other guideline. In addition, the evidence content varied between guidelines: CCA guidelines relied on evidence showing that most patients detect their own recurrence 19; ASPS guidelines relied on the finding that second primaries are thinner than first primaries or are thinner in those patients who are educated 18; American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) relied on both 20. SIGN guidelines relied on evidence showing that information provision can reduce distress and possibly thereby improve survival 17. COG, ESMO, SAKK, NCCN and BAD provided no evidence to support this recommendation 16,21–24.

Follow-up frequency and duration

Recommendations for the frequency and duration of follow up are summarised in Table3. CCA was the only guideline to mention that the frequency of follow up may be affected if a patient is enrolled in a clinical trial 19. Although all guidelines recommended follow up for medium-to–high-risk melanoma patients, they offered little or no evidence to support its use. CCA, AAD, ASPS, BAD and SAKK acknowledged that most melanoma recurrences are detected by the patient 18–20,23,24, but BAD also suggested that physician detection of melanoma is important 24. A prospective study by Garbe et al. 25 that claims to demonstrate the efficacy of routine follow up was cited by CCA, SIGN and the AAD guidelines 17,19,20, although the study does not exclude the possibility of lead time bias. The BAD 24 guidelines referenced a consensus-based guideline also written by Garbe et al. 26. The SAKK 23 guidelines share some authors with the ESMO 22 guidelines and cite another German guideline written by Garbe et al. 27. The SAKK and ESMO guidelines also cite each other 22,23. The CCA, ASPS, SIGN and AAD 17–20 guidelines cite a range of studies that show there is no survival advantage for patients receiving intense routine surveillance: Baughan et al. 28 cited by CCA; Hofmann et al. 29 cited by CCA, ASPS and AAD; Shumate et al. 30 cited by SIGN; Mooney et al. 31 cited by SIGN and CCA; Tsao et al. 32 cited by ASPS. The NCCN guidelines only cite studies published in the early 1990s relating to psychosocial support, detection of a subsequent secondary primary melanoma and screening for second non-melanoma primary malignancies as reasons in favour of a structured follow-up programme 21. ESMO's only recommendation relating to frequency of follow up states that there is no consensus on the optimal schedule 22.

Table 3.

Follow-up frequency and duration

| Guideline | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| CCA | Stage 0: No recommendation Stage I: 2/year (first 5 years), then 1/year Stage II: 3–4/year (first 5 years), then 1/year Stage III: 3–4/year (first 5 years), then 1/year Stage IV: No recommendation |

| SIGN | Stage 0: No follow up required Stages I–III: ‘longer in stage III than in stages I and II’ Stages III–IV: ‘lifelong follow up may be necessary for stages III and IV’ |

| BAD | Stage 0: No follow up required Stage IA: 2–4/year (first year), then discharge Stages IB–IIIA: 4/year (first 3 years), then 2/year (next 5 years), then discharge Stages IIIB-C and resected IV: further follow up of 1/year (for 10 years) |

| ASPS | No stage specified: 4/year (first year), then 2/year (for 5 years), then at least 1/year (more frequently for high-risk patients) |

| COG | No stage specified: Annual follow up with monthly self-exam |

| AAD | No stage specified: Annual follow up |

| ESMO | There is no consensus on the optimal follow-up schedule and frequency of follow up |

| SAKK | Stage 0: No recommendation Stage I (≤T1N0): every 6 months (years 1–3), every 12 months (years 4–10) Stages I (T2N0), IIA, IIB: every 6 months (years 1–3), every 12 months (years 4–5), every 6–12 months (years 6–10) Stages IIC, III: every 3 months (years 1–5), every 6 months (years 6–10) Stage IV: ‘individual’ |

| NCCN | Stage 0: At least annual skin exam for life; monthly self skin exam Stages IA–IIA: every 3–12 months (first 5 years), then annually as clinically indicated, monthly self skin exam Stages IIB–IV: every 3–12 months (first 5 years), then every 3–12 months (for 3 years), then annually as clinically indicated; monthly skin self-examination |

Text in quotations is taken directly from the guidelines.

Diagnostic/imaging tests

Recommendations for the use of diagnostic/imaging tests as part of follow-up care are summarised in Table4. All the recommendations for the use of tests in follow up are based on low-level evidence, primarily case series, diagnostic accuracy studies or prognostic cohort studies. With one exception, the studies used to support the SIGN 17 guideline recommendations were published before 2000. Similarly, the studies used by CCA 19 to reject the use of tests except for ultrasound are also pre-2000. NCCN 21 cites studies that report low yield, significant rates of false positives and risks of radiation exposure from medical imaging, but still recommend that imaging should be considered in some cases. CCA and SAKK recommend the use of ultrasound in high-risk patients 19,23, whereas AAD and SIGN – using similar evidence – do not 17,20. ESMO recommends a serum S-100 blood test instead of lactate dehydrogenase because it has higher specificity for disease progression, i.e. ‘if any blood test is done at all’ 22, and in another recommendation states that there is no consensus on the utility of imaging and blood tests 22.

Table 4.

Diagnostic/imaging tests

| Guideline | Ultrasound | Chest X-rays | CT scans | PET-CT scans | MRI | Liver function tests | Blood test/count | Lactate dehydrogenase | Serum S-100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCA | Stage IV | No | No | No | No | No | |||

| SIGN | No | No | No | No | No | No | |||

| BAD | No | Consider in stages IIIB–IV | No | No | No | Stage IV | |||

| ASPS 18 | Stage II or II, and patients with possible systemic involvement | Stages II and III | Stages II and III | ||||||

| COG | |||||||||

| AAD | No | No | No | No | No | Stage IV | |||

| ESMO | No | Yes | |||||||

| SAKK | Stages I (T2N0)–IV | Stages I (T2N0)–IV | Stages IIC–IV | Stages IIC–IV | Stages IIC–IV | Stages I (T2N0)–IV | |||

| NCCN | Consider in stages IIB–IV | Consider in stages IIB–IV | Consider in stages IIB–IV | Consider in stages IIB–IV |

‘No’ indicates that the test was recommended against. Blank areas indicate that no recommendation was made.

AGREE II domains

The AGREE II instrument domain scores for each guideline, averaged across the four reviewers, are given in Table5. The two domains of greatest interest for the authors, given the purpose of this study, were ‘rigour of development’ and ‘overall guideline quality’.

Table 5.

AGREE II instrument domain scores

| Guideline | Scope and purpose (%) | Stakeholder involvement (%) | Rigour of development (%) | Clarity of presentation (%) | Applicability (%) | Editorial independence (%) | Average overall score | Would you recommend this guideline for use? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCA | 61 | 83 | 95 | 85 | 26 | 44 | 5.8 | 3 Yes 1 Yes, with modifications |

| SIGN | 61 | 86 | 60 | 86 | 61 | 10 | 5.0 | 4 Yes, with modifications |

| BAD | 33 | 54 | 50 | 94 | 42 | 46 | 5.0 | 2 Yes 2 Yes, with modifications |

| ASPS | 47 | 26 | 44 | 75 | 3.1 | 2.1 | 4.0 | 3 Yes, with modifications 1 No |

| COG | 71 | 93 | 79 | 82 | 42 | 79 | 6.0 | 4 Yes |

| AAD | 60 | 31 | 29 | 74 | 3.1 | 83 | 2.8 | 4 No |

| ESMO | 15 | 21 | 20 | 65 | 4.2 | 27 | 2.5 | 4 No |

| SAKK | 46 | 25 | 21 | 39 | 8.3 | 56 | 3.0 | 4 No |

| NCCN | 28 | 44 | 29 | 60 | 14 | 35 | 3.5 | 4 Yes, with modifications |

| Mean | 46.9 | 51.4 | 47.4 | 73.3 | 22.6 | 42.5 |

Rigour of development

This domain encompasses 8 of the 23 items in the AGREE II instrument 8. Methods used to search for evidence were adequate in most guidelines, but only CCA 19 searched a wide variety of databases, listed time periods searched, search terms used and included an appendix detailing the whole search strategy. Description of the criteria used for selecting evidence was relatively poor for most guidelines, with some guidelines only mentioning language type and most not mentioning eligibility criteria such as study design or health outcomes of interest. A formal grading system and appraisal of literature were necessary for the guideline to receive a high AGREE score on this domain because the system enables a description of the strengths and limitations of the guidelines’ body of evidence. In addition, it was essential that there was some consideration of consistency of results across studies and their applicability in practice. Expert consensus was often stated as the method used for formulating recommendations. Guidelines that described their methods for obtaining consensus [COG 16] scored more highly than those merely stating that a consensus process had been employed [ASPS 18]. ESMO, SAKK and NCCN guidelines did not state any method for formulating recommendations 21–23. Health benefits, side effects and risks were adequately outlined in most guidelines, nevertheless appraisers thought that the explicit discussion of complications and side effects was lacking in AAD and ASPS 18,20. The way that guidelines linked evidence to recommendations varied greatly. The most transparent format was that of the NHMRC-endorsed CCA 19 guidelines, which comprised an evidence summary box with references and grading of the level of evidence for each individual recommendation. Most guidelines were able to demonstrate congruency between the evidence and the recommendations. The ESMO guidelines provided in-text referencing, but lacked a link between recommendations and evidence 22. Guidelines with no expert external review at all were scored poorly, whereas those with detailed explanations of the purpose, method and outcomes received higher scores. Guidelines that included information about how outcomes of the external review were applied to the guideline development process generally scored higher than those that did not. Better guidelines usually included a methodology or timeline for updating the guideline rather than a simple statement that the guideline would be updated.

Overall guideline quality

Ultimately, the COG 16 guidelines were rated as having the best quality, with highest scores in two of six domains. The CCA 19 guidelines were also unanimously recommended for use; however, one reviewer noted that there were some gaps in the guideline, such as the lack of auditing criteria. Modifications suggested for the SIGN 17 guidelines included better discussion of article selection, applicability and more information regarding editorial independence. Two appraisers would modify the BAD 24 guidelines to include detailed criteria for selecting evidence and consideration of potential resource implications of applying the recommendations. The ASPS 18 guideline was recommended with modifications by three appraisers and not recommended by one on the grounds that the guideline was generally vague and tended to describe current practice rather than provide evidence-based recommendations. The other three reviewers noted that although there were deficiencies in some applicability and editorial independence items, methodological rigour and clarity of presentation were good. The AAD 20 guidelines received higher domain scores than ASPS 18 in three of the six domains, and equal scores in another domain and slightly less than ASPS in another domain. Nevertheless, ASPS 18 received more favourable recommendations than AAD 20, with the appraisers noting that AAD guidelines – according to AGREE criteria – lacked transparency, rigour and multidisciplinary engagement. NCCN 21 guidelines did not report on some of the methodological features included in other guidelines, but were clearly presented and slightly more rigorous than SAKK guidelines 23. ESMO 22 guidelines were brief and did not report on most methodological features usually expected to be included in an evidence-based clinical practice guideline.

Discussion

Summary of main finding

The paucity of evidence in the field of melanoma follow up has been borne out by the comparison of melanoma follow-up guidance in this review. All guidelines described the lack of evidence to support guidance on the frequency of follow-up visits. As there is no international consensus regarding what constitutes best practice for follow up of melanoma survivors, the recommendations included in the guidelines are based primarily on the relapse profile over time. Generally, the guidelines propose that the more advanced the stage of disease, the more frequent the appointments should be and that the frequency should be higher during the early follow-up period as recurrence is more likely in patients with advanced disease 33 and in the first years following diagnosis 34. However, the intervals prescribed are ‘arbitrary’ and there is significant variation in the recommendations that have been made 19. Similarly, as the evidence base for the effectiveness of skin examination and diagnostic imaging was also sparse and of low quality, the ensuing recommendations made by guideline developers have been largely developed through consensus and vary as a consequence.

Context of this review with other literature

These findings are very similar to those of a systematic review of clinical practice guidelines dealing with prostate cancer follow up 12, which also revealed poor methodological quality and lack of transparency in consensus procedures, in the context of paucity of evidence in that field of research. Another study assessing six British cardiovascular guidelines published by professional societies using AGREE II found serious methodological deficiencies in all guidelines and did not recommend any guideline for clinical practice 13. In recent years, approaches have been developed to increase transparency in the development of guideline recommendations, most noticeably the Australian FORM system, recommended by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) 35, which mandates the use of an evidence statement form that transparently depicts how developers move from evidence to making a judgement and formulating a recommendation. This methodological approach was used by the CCA guideline, which received the highest scores in our AGREE II evaluation with regards to rigour of development. Similarly, the GRADE system – which has been promoted heavily worldwide – provides a more standardised approach to the development of recommendations 36. None of the guidelines appeared to use GRADE when formulating recommendations.

Strengths and limitations

Some guidelines may have scored poorly as a result of insufficient reporting, rather than deficient quality. A potential weakness of this study is that guideline authors were not contacted to confirm findings. Hence, the scores might not be an accurate reflection of the guideline development process. Alternatively, they may highlight problems in reporting by guideline development groups.

The AGREE II instrument has some potential weaknesses, e.g. the items and scoring system may be interpreted differently by appraisers, regardless of the application of the ‘user's manual description’, ‘how to rate’ and ‘additional considerations’ sections provided for each item 8. Moreover, it was suggested by one appraiser that the addition of an item to specifically assess the provision of tools for patients that complement clinical practice guidelines would be beneficial.

It should also be noted that AGREE II scores do not aim to rate the quality of the recommendations or their supporting evidence 8. For example, COG 16 guidelines attained a relatively high ‘rigour of development’ score, yet the evidence provided in that guideline for melanoma follow up was limited. Therefore, caution should be exercised as guideline quality according to AGREE II domains reflects the methodology of the guideline development and does not reflect the availability of good evidence 8. Nevertheless, it is evident that guidelines with low scores in the rigour of development domain tended to provide less evidence for their recommendations.

Following the completion of our literature searches and data analysis, NCCN released their annual update to their guideline. Their melanoma follow-up guidance remains unchanged. This change does not impact on the findings of this study. The SIGN guidelines were reaffirmed in 2011 and remain current, although SIGN recommends the guidelines be used with caution as they are over 7 years old.

Conclusions and implications

This review examines current international guideline recommendations for follow up of patients with cutaneous melanoma. The evidence base for each guideline was evaluated and the AGREE II instrument was utilised for the appraisal of guideline quality. Although most recommendations were evidence based, the level and strength of evidence employed was often low. Moreover, given the lack of clear direction from the evidence base, recommendations were often inconsistent between guidelines. All guidelines acknowledged the lack of evidence to some extent and the need for further research in the field of melanoma follow up. Clinicians should recognise that further investigation into the methodology and evidence behind the development of recommendations are required to fully understand the significance of melanoma follow-up recommendations in the clinical setting.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Vacation Scholarship, University of Adelaide and by National Health and Medical Research Council Capacity Building, Health Care in the Round (grant number 556501 to Jackie Street and Nino Marciano).

Author contributions

Nino Marciano contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the project and the writing of the manuscript. Tracy Merlin contributed to the conception, design, analysis and interpretation of the project and the writing of the manuscript. Taryn Bessen contributed to the conception, design, analysis and interpretation of the project and the writing of the manuscript. Jackie Street contributed to the conception, design, analysis and interpretation of the project and the writing of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Godar DE. Worldwide increasing incidences of cutaneous malignant melanoma. J Skin Cancer. 2011;2011:858425. doi: 10.1155/2011/858425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ACIM. Australian Cancer Incidence and Mortality Books. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6199–206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cancer and Screening Unit of the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer in Australia: An Overview, 2010. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ugurel S, Enk A. Skin cancer: follow-up, rehabilitation, palliative and supportive care. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008;6:492–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2008.06675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murchie P, Hannaford PC, Wyke S, et al. Designing an integrated follow-up programme for people treated for cutaneous malignant melanoma: a practical application of the MRC framework for the design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. Fam Pract. 2007;24:283–92. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmm006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Field MJ, Lohr KN. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1992. Guidelines for clinical practice: from development to use. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182:E839–42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forbes D, Creamer M, Bisson JI, et al. A guide to guidelines for the treatment of PTSD and related conditions. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23:537–52. doi: 10.1002/jts.20565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guidelines International Network. About G-I-N. 2013. http://www.g-i-n.net/about-g-i-n (accessed 27 September 2013)

- 11.AGREE Collaboration. Development and validation of an international appraisal instrument for assessing the quality of clinical practice guidelines: the AGREE project. Qual Safety Health Care. 2003;12:18–23. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McIntosh HM, Neal RD, Rose P, et al. Follow-up care for men with prostate cancer and the role of primary care: a systematic review of international guidelines. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1852–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minhas R. Eminence-based guidelines: a quality assessment of the second Joint British Societies’ guidelines on the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61:1137–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Speijers MJ, Francken ABB, Hoekstra-Weebers JEHM, et al. Optimal follow-up for melanoma. Expert Rev Dermatol. 2010;5:461–78. [Google Scholar]

- 15.The ADAPTE Collaboration. Resource toolkit for guideline adaptation. 2007. http://www.adapte.org/www/upload/actualite/pdf/Manual%20&%20Toolkit.pdf (accessed 25 September 2013)

- 16.Children’s Oncology Group. Long-term Follow-up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent and Young Adult Cancers. Arcadia, CA: Children's Oncology Group; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guideline Development Group. Edinburgh: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network; 2003. Cutaneous melanoma. A national clinical guideline. Internet. [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Evidence-based Clinical Practice Guideline: Treatment of Cutaneous Melanoma. Arlington Heights, IL: American Society of Plastic Surgeons; 2007. Internet. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Australian Cancer Network & New Zealand Guidelines Group. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Melanoma in Australia and New Zealand. Wellington: Cancer Council Australia; 2008. Internet. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bichakjian CK, Halpern AC, Johnson TM, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of primary cutaneous melanoma. American Academy of Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1032–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coit DG, Andtbacka R, Anker CJ, et al. Melanoma. Fort Washington, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2012. Internet. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dummer R, Hauschild A, Guggenheim M, et al. Cutaneous melanoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:vii86–91. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dummer R, Guggenheim M, Arnold AW, et al. Updated Swiss guidelines for the treatment and follow-up of cutaneous melanoma. Swiss Med Wkly. 2011;141:w13320. doi: 10.4414/smw.2011.13320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marsden JR, Newton-Bishop JA, Burrows L, et al. Revised UK guidelines for the management of cutaneous melanoma 2010. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63:1401–19. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garbe C, Paul A, Kohler-Spath H, et al. Prospective evaluation of a follow-up schedule in cutaneous melanoma patients: recommendations for an effective follow-up strategy. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:520–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garbe C, Hauschild A, Volkenandt M, et al. Evidence and interdisciplinary consensus-based German guidelines: surgical treatment and radiotherapy of melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2008;18:61–7. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e3282f0c893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garbe C, Schadendorf D, Stolz W, et al. Short German guidelines: malignant melanoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008;6(Suppl. 1):S9–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2008.06711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baughan CA, Hall VL, Leppard BJ, Perkins PJ. Follow-up in stage I cutaneous malignant melanoma: an audit. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 1993;5:174–80. doi: 10.1016/s0936-6555(05)80321-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hofmann U, Szedlak M, Rittgen W, et al. Primary staging and follow-up in melanoma patients–monocenter evaluation of methods, costs and patient survival. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:151–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shumate CR, Urist MM, Maddox WA. Melanoma recurrence surveillance. Patient or physician based? Ann Surg. 1995;221:566–9. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199505000-00014. discussion 9-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mooney MM, Kulas M, McKinley B, et al. Impact on survival by method of recurrence detection in stage I and II cutaneous melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 1998;5:54–63. doi: 10.1007/BF02303765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsao H, Feldman M, Fullerton JE, et al. Early detection of asymptomatic pulmonary melanoma metastases by routine chest radiographs is not associated with improved survival. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:67–70. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White RR, Stanley WE, Johnson JL, et al. Long-term survival in 2,505 patients with melanoma with regional lymph node metastasis. Ann Surg. 2002;235:879–87. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200206000-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dicker TJ, Kavanagh GM, Herd RM, et al. A rational approach to melanoma follow-up in patients with primary cutaneous melanoma. Scottish Melanoma Group. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:249–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hillier S, Grimmer-Somers K, Merlin T, et al. FORM: an Australian method for formulating and grading recommendations in evidence-based clinical guidelines. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Schunemann HJ, et al. GRADE guidelines: a new series of articles in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:380–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]