Key messages

New organisations were created with a mandate to lead the establishment of Local Health Networks with several partners such as primary healthcare organisations.

Various strategies were put in place to improve collaboration across and between primary healthcare organisations working in communities; for example, the implementation of new models of primary healthcare, improving access to specialists and diagnostic tests for family physicians, improving services for chronic disease in the community and helping unattached patients to find a family physician.

The planning and organisation of health services became more focused on the population of a local territory. This new mandate was based on a ‘population-based responsibility’.

Approximately 10 years have passed since the implementation of this large-scale redesign of the healthcare system in Québec, and many changes are still required.

Why this matters to us

‘Integrated care’ is a buzzword when it comes to improving healthcare services. There is a consensus among researchers, decision-makers and clinicians that services should be developed based on a network of integrated care. There are different ways to achieve this goal. The province of Québec used legislation to formally mandate healthcare organisations to function within newly created and geographically delimited Local Health Networks. Some lessons can be learned from this experiment in the province of Québec.

Keywords: integrated care, mandated reform, networks, primary healthcare

Abstract

Background In 2004, the Québec government implemented an important reform of the healthcare system. The reform was based on the creation of new organisations called Health Services and Social Centres (HSSC), which were formed by merging several healthcare organisations. Upon their creation, each HSSC received the legal mandate to establish and lead a Local Health Network (LHN) with different partners within their territory. This mandate promotes a ‘population-based approach’ based to the responsibility for the population of a local territory.

Objective The aim of this paper is to illustrate and discuss how primary healthcare organisations (PHC) are involved in mandated LHNs in Québec. For illustration, we describe four examples that facilitate a better understanding of these integrated relationships.

Results The development of the LHNs and the different collaboration relationships are described through four examples: (1) improving PHC services within the LHN – an example of new PHC models; (2) improving access to specialists and diagnostic tests for family physicians working in the community – an example of centralised access to specialists services; (3) improving chronic-disease-related services for the population of the LHN – an example of a Diabetes Centre; and (4) improving access to family physicians for the population of the LHN – an example of the centralised waiting list for unattached patients.

Conclusion From these examples, we can see that the implementation of large-scale reform involves incorporating actors at all levels in the system, and facilitates collaboration between healthcare organisations, family physicians and the community. These examples suggest that the reform provided room for multiple innovations. The planning and organisation of health services became more focused on the population of a local territory. The LHN allows a territorial vision of these planning and organisational processes to develop. LHN also seems a valuable lever when all the stakeholders are involved and when the different organisations serve the community by providing acute care and chronic care, while taking into account the social, medical and nursing fields.

Canadian context

In Canada, the responsibility for organising primary care services has historically been left to autonomous community-based private medical practices owned by a physician or a group of physicians.1 This situation stands in sharp contrast to that of institutions, such as hospitals and community centres, which form an integral part of the public system. It was therefore not surprising that several provincial and federal committees have recognised problems related to the organisation of primary medical services. Thus, over the past several years, Canadian politicians, decisionmakers, clinicians and researchers have reached a consensus about reforming primary care services as a key strategy for improving healthcare system performance. However, it is only fairly recently that substantive initiatives have been launched in various Canadian provinces aimed at transforming primary care services.2

Historical background of the province of Québec

The Québec healthcare system has undergone considerable change that has especially affected primary healthcare (PHC). Québec is a province of over 8 million residents with a tax-based system providing universal access to medical services. Healthcare organisations, such as community health centres and hospitals, receive block funding from the Ministry of Health and Social Services. Fewer than 20% of family physicians work in public primary health organisations, called local community service centres, and are paid a salary. The remuneration of family physicians working in primary care private practice is predominantly on a fee for services basis, even where several new modes of mixed remuneration have been put in place to encourage the follow-up of patients in the community. However, other types of remuneration such as small per capita fee for enrolling patients and a bonus for taking unattached patients through a centralised waiting list represents less that 20% of the remuneration of family physicians working in a private primary healthcare practice.

Formal enrolment of patients with physicians is relatively new. Enrolment payments were instituted in the early 2000s with the introduction of a new primary care model, family medicine groups (FMG). It was only in 2009, that these enrolment payments were extended to all other family physicians practising outside FMGs. These payments are based on clientele characteristics and constitute the beginnings of a capitation model, but without penalties or requirements for physicians to provide a minimal level of services to patients in order to receive these payments.

While nearly all family physicians provide medical services reimbursed by the public Medicare programme, most primary healthcare practices are private enterprises. The responsibility for organising primary healthcare services has historically been left to these communitybased private medical practices owned by a physician or a group of physicians. This situation stands in sharp contrast to that of other healthcare organisations, such as hospitals or community health centres, which are under public administration and form an integral part of the public system.

Until recently, although physicians were reimbursed for their services by the public health insurance system,3 there had been very little public investment in primary healthcare services delivered privately. Delivery of primary healthcare was at the periphery of the system rather than at its core.4 Thus, historically, private medical clinics have been the dominant type of primary healthcare organisations in Québec, and they established very few relationships with public healthcare organisations such as local community service centres that provide social services and homecare, long-term care facilities or hospital care.

Description of the mandated Local Health Network (LHN)

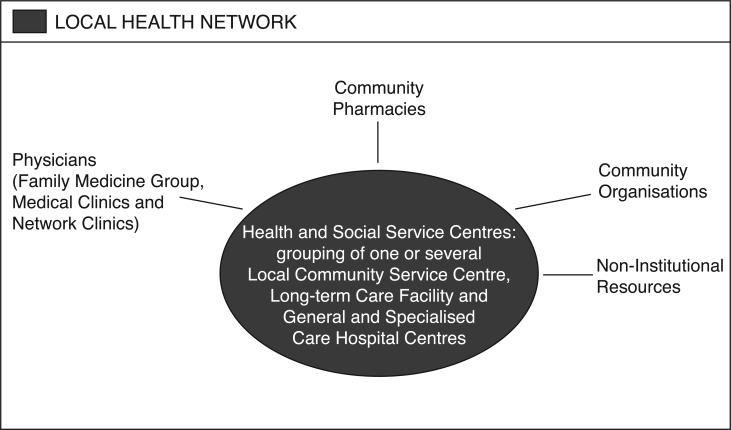

In 2004, the Québec government initiated a large-scale redesign of its healthcare system with the objective of improving service accessibility, continuity, integration and quality for the population of a given area, by organising healthcare services into 94 geographically delimited Local Health Networks (LHN) across the province. At the heart of the each LHN, a new organisation called a Health and Social Services Centre (HSSC) was created by an administrative merger local community health centres, long-term care facilities and, in 85% of cases, an acute care hospital.5 The merger of all these organisations to form the HSSCs is illustrated in Figure 1. Each HSSC was formally mandated to lead the creation of an integrated LHN by encouraging the establishment of formal or informal arrangements among various other providers currently offering services within its territory such as family physicians, community pharmacies.6 LHN covers wide geographical areas across Québec, whether urban and rural. The population located into the LHN boundaries varies from 20 000 to 250 000 people.

Figure 1.

Conceptualisation of the Local Health Network implemented across Québec.

Potential of LHNs

The HSSCs had the mandate to lead the development of LHNs in order to address the needs of the population in each geographical area. In addition to being responsible for the clientele who seek healthcare services from them, the HSSCs were given a new population-based responsibility. This means that the HSSCs are responsible for improving the health and well-being of their geographically defined population. This represents an important shift in the way that healthcare delivery is planned and executed because the approach consists of reaching out to people who may not usually seek services and adapting the services to the needs of the local population. This way of organising healthcare has a lot in common with the traditional conception of public health.

In 2002, based on a systemic view, Kodner and Spreeuwenberg wrote that ‘integrated care is a burgeoning field’.7 These authors have proposed a concept of integration as ‘a coherent set of methods and models on the funding, administrative, organisational, service delivery and clinical levels designed to create connectivity, alignment and collaboration within and between the care and the cure sectors’ (p. 3). Based on this definition, the integration may be shaped in a hierarchical approach that focuses on administrative tools or by a bottom-up approach that focuses on the patients and practitioners at large. The question is how to join these two seemingly opposed clinical and administrative approaches.8,9 In fact, definitions and models of integrated care have often focused on coordination and collaboration between health professionals across the continuum of care for individual patients and much less on interorganisational collaborations.10 Yet, the increasingly complexity of health issues is such that no single organisation is able to resolve the issues alone. This needs crossorganisational boundaries and requires a collective effort.11 That is why the implementation of LHNs that encourage and improve the relationships among primary care practices

Links between HSSC and Québec's primary healthcare practices

The HSSC responsibility to plan and implement services within the LHN involves enhancing access to comprehensive primary care and facilitating collaboration among the various partners located in their territories. These collaborations are developed with several objectives such as: (1) improving PHC services within the LHN; (2) improving access to specialists and diagnostic tests for family physicians working in the community; (3) improving chronic-disease care services for the population of the LHN; and (4) improving access to family physicians for the population of the LHN. Below, we present some brief examples of improved collaborations with family physicians working in the community since the HSSCs were formally mandated to develop the LHNs.

Example 1: Improving PHC services within the LHN

To address the lack of integration of primary healthcare organisations with the rest of the healthcare system, new types of primary healthcare models were introduced starting in 2002 to increase care accessibility and continuity, namely FMGs or network clinics.

Based on contractual agreements with the provincial government and a formal accreditation process, an FMG comprises a group of physicians working in close collaboration with at least one nurse to provide services to registered patients on a non-geographical basis (usually around 10 000 to 20 000 people per FMG). The FMG reform funded the recruitment of nurses and administrative staff, and the acquisition of computer equipment. Physicians are each responsible for their clientele, but medical records are available to all physicians. The FMG provides services by appointment and on a walk-in basis. Nonetheless, these services are for registered members only.12 Accessibility is expected to improve by extended hours of operation and by a regional on-call system of doctors or clinics for vulnerable patients. Since the FMG policy was inaugurated in 2002, the number of accredited practices has been increasing steadily. The Ministry of Health and Social Services affirmed in January 2014 that there were 253 accredited FMGs in Québec, enrolling more than 50% of the province's population.

Because FMGs provide services exclusively to registered patients, a new model – the network clinic – was introduced to serve the accessibility needs of non-registered patients and to provide more robust diagnostic support at the primary care level. Network clinics have been established in many regions through contractual agreements with the Regional Health Authorities.11 Network clinics are large privately owned group practices providing extended hours of clinical services. Services are provided seven days a week and network clinics have direct on-site access to extended diagnostic services such as imagery and laboratory testing.12

Since the reform, the HSSCs have tried to improve the offer and delivery of primary healthcare within their geographical boundaries. For instance, some HSSC managers conducted visits in all medical clinics located on their territories: first, to improve their knowledge of the services delivered within the LHNs; and second, to improve the collaboration with them. Many HSSCs have offered support through the accreditation process to medical clinics interested in becoming part of the new PHC model – such as FMG and network clinics. Delivering on the promise to improve the PHC services in their LHN territory is particularly a challenge in urban areas where LHN boundaries are not perceptible to the population and patients have the right to seek care from the institution of their choice. Nonetheless, most HSSCs held firm to the philosophy to improve the delivery of PHC services on their territory, even when the patients served resided outside the LHN boundaries, but most urban HSSCs now monitor the extent of out-of-boundary service provision.

A recent study on interorganisation collaboration showed that, on a locally integrated basis, the impact of Québec's reform mainly comprised improved collaboration between the new types of PHC organisations supported by the reform, and the HSSCs.11 The LHN reform seems to have improved collaboration within LHN areas between all healthcare organisations except for the private medical clinics outside the new PHC models, where collaboration has actually deteriorated both inside and outside the LHNs.11 It appears that independent physician-owned or small-group practices have withdrawn and disengaged from the activities organised at the level of the LHN. Transforming and integrating this type of clinic into the LHN is the next primary healthcare challenge in Québec. In order to have an impact on the population accessibility and quality of care, improvement initiatives need to apply to the majority of organisations.

Example 2: Improving access to specialist services and diagnostic tests for family physicians within the LHNs

Access to specialist services is a major challenge and there can be long delays for referrals or for diagnoses.13,14 Moreover, formal collaboration between the primary and secondary services is not optimal. Indeed, depending on the contacts, family doctors may rely on social networks for their patients to gain timely access to a specialist, or may encourage patients to access needed diagnostic and therapeutic services at the local hospital. In order to meet some specialised health-service needs, some HSSCs have established a centralised access to specialist services for family physicians working in the community. The ultimate goal is to meet the needs of the population and of the physicians working in the community.15

This centralisation allows family physicians to access technical platforms and diagnostic consultations with specialists, and in some cases, individual therapy (intravenous antibiotic administration, blood transfusion, etc.) for patients who meet given criteria of need. The objective of this centralised access is to allow quick investigation and continuous monitoring to enable physicians to optimise patient management, minimise delays in addressing requests, facilitate the information flow between physicians and avoid the use of emergency services. In the end, this type of organisation facilitates gradual improvements in the collaboration between community-based family physicians and specialists working within the LHN.15 It has also been recognised that this type of organisation can potentially reduce the number of references to emergency services.16

At the operational level, consultation requests from family physician to a specialist are sent to a centralised list where a nurse prepares the patients and clinical examination requests for the specialist. This allows quick access to a specialist and technical platforms for certain predetermined conditions. However, no evaluation of the impact of this centralised access has been conducted to date.

Example 3: Improving chronic disease services for the population of the LHN

The Canadian public system was developed to respond to catastrophic and episodic illness and required an intentional investment to adapt to the increasing burden of chronic illness. The case of diabetes – a major chronic disease within Québec's population – was one area in which several HSSC developed innovative projects.17 One HSSC was among the leader in the field by developing a Diabetes Reference Centre which has won many prizes and rewards.18

This innovative Diabetes Reference Centre, which regroups physicians, nurses, social workers, nutritionists, pharmacists and physiotherapists, was opened in 2007 in one HSSC on Montréal. The Diabetes References Centre comprises two programmes: (1) a lifestyle-change programme, and (2) a teaching and treatment programme. The lifestyle-change programme is designed to restore normal biological indicators and to prevent complications in people newly diagnosed with diabetes. In individual and group meetings with a physiotherapist, a nurse and a nutritionist, the patient focuses on improving their quality of life through exercise, diet and a better understanding of their illness, always remaining connected to their family physician. The second programme includes a three-day course designed for patients with more advanced disease and suffering from complications or side effects.

The HSSC where the Diabetes Reference Centre is located serves over 10 000 diabetic patients with more than 800 new cases every year. The emergency service of this HSSC treats the most severe cases of diabetes.19

The clinical programme of this HSSC is based on interdisciplinary networking. It advocates the integration of resources, the training of workers and the development of formal connections with the community. Thus, the HSSC, general practitioners and specialists collaborate more closely and share a common goal, which is the optimal treatment of people with diabetes. This programme is currently being evaluated by the regional health agency, but it is already recognised by several stakeholders and clinicians in the region that this service has united the efforts of all the stakeholders involved in diabetes, and established a real network of services for the population in the territory. After broadening its service to respond better to the needs of its diabetes population, the HSSC has targeted another chronic disease, namely, cardiovascular disease. Based on its previous success initiated by the number of patients used their services, and because these two diseases are closely related and have the same risk factors, the HSSC decided to expand the range of services offered at the Diabetes Reference Centre and subsequently renamed it the Chronic Disease Action Centre.

As a consequence, this type of partnership, reinforced by the development of a shared local leadership at the HSSC level, contributes to a new way of organising and planning for primary healthcare service delivery on the territories of the Province. Furthermore, family physicians have easier access to educational services for their diabetic clients and also have easier access to the specialists of the HSSC for monitoring complex cases. Also, building on these positive results, several other HSSCs implemented a similar project. It thus became a model for other actors that attempted to reproduce this project in their own organisation.18

Example 4: Improving access to family physicians for the population of the LHN

In Québec, nearly 29% of the population do not have a family physician.20 Although patients have the right to seek care from any physician or hospital without charge, few family physicians accept new patients. Not having a family physician drastically reduces a person's access to timely services and comprehensive care. In response to this important population need, the Québec government has created centralised waiting lists for patients without a family physician in order to help unattached patients find a family physician. These centralised waiting lists were taken into account by the HSSC governance. There are aligned with the population-based responsibility of the HSSCs. The aim of these centralised waiting lists is two-fold: (1) to increase the number of patients that have a family physician, and (2) to give priority to vulnerable patients. The government defined the general orientation of this innovation and the HSSCs were given flexibility in the financing and organisation of these lists.

Referrals may be made to the centralised waiting lists from different sources. Patients may subscribe to the list, by telephone or online, or by sending a postal form. Patients may also be referred by a health professional following a clinic consultation, an emergency room visit, a hospitalisation or in any other carerelated context. When patients are registered in a centralised waiting list, they are assigned a priority code based on the health urgency and complexity of the case. This code is determined by a nurse in collaboration with the local medical coordinator. Standards regarding waiting times for enrolment with a family physician, in accordance with the priority codes, are set by the Ministry of Health and Social Services. Finally, family physicians receive a financial bonus for unattached patients enrolled through the centralised waiting lists.

However, the information required to assess whether these innovations actually helped improve access to family physicians is limited. So far, over 600 000 patients have been associated with a family physician through the centralised waiting lists since their implementation across the Province in 2008.21 Yet, we know that there are significant variations in the performance of those centralised waiting lists across Québec in terms of the number of patients linked with a family physician, their characteristics and the delays.22 In these structures, operating rules, resources and professionals’ roles and responsibilities are established locally, which causes wide variation in the number of patients registered with a family physician through this structure. This results in inequity in access between the different centralised waiting lists across the province.

Discussion

What have we learned from the LHN mandate given to lead organisations in Québec? Ten years after the implementation of the LHN reform, important issues remain with regard to access and continuity. The mandate to create LHNs has created a new opportunity to establish better relationships with PHC organisations.

Against a historical background that favoured a client-focused and episodic response from hospitals and PHC organisations, the shift toward a ‘population-based responsibility’ changes the frontier of the organisation to more a ‘territorially based responsibility’, where HSSCs seek to improve service delivery to the population within their geographical boundaries. This change of vision creates a space for innovation in the way in which healthcare is organised.

Through various examples, we have seen that the implementation of this large-scale reform involves incorporating actors at all levels (strategic, tactical and clinical). Several examples show different strategies taken by stakeholders to respond to their new mandate of establishing LHNs. Since the implementation of LHNs in Québec, we have not observed significant improvement regarding the care experience of patients as recorded in Commonwealth Fund survey.23 However, time may intensify the success of this change and the change at a population level because breaking silos always has the potential to develop a stronger system, based on primary care services.

Contributor Information

Mylaine Breton, Professeure adjointe, Faculté de Médecine et des sciences de la santé, Centre de recherche – Hôpital Charles-Le Moyne, Longueuil (Québec), Canada.

Lara Maillet, École d'administration publique de l'Université de Montréal (ESPUM), Université de Montréal, Montréal (Québec), Canada.

Jeannie Haggerty, Associate Professor and Research Director, Department of Family Medicine, Centre hospitalier de St. Mary, Département d'épidémiologie clinique et d'études communautaires, Montréal (Québec), Canada.

Isabelle Vedel, Assistant Professor, Department of Family Medicine, McGill University, Montréal, (Québec), Canada.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None Declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Breton M, Denis JL, Lamothe L. Incorporating public health more closely into local governance of health care delivery: lessons from the Québec experience. Canadian Journal of Public Health 2010;101:314–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hutchison B. A long time coming: primary healthcare renewal in Canada. HealthcarePapers 2008;8(2):10–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breton M, Levesque JF, Pineault R. et al. Primary care reform: can Québec's Family Medicine Group Model benefit from the experience of Ontario's Family Health Teams. Healthcare Policy 2011;7(2):e122–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hutchinson B, Levesque JF, Strumpf E. et al. Primary health care in Canada: systems in motion. Milbank Quarterly 2011;89:256–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denis J-L, Lamothe L, Langley A. et al. The reciprocal dynamics of organizing and sense-making in the implementation of major public-sector reforms. Canadian Public Administration 2009;52:225–48 10.1111/j.1754–7121.2009.00073.x [published OnlineFirst: 03/06/09]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vedel I, De Stampa M, Bergman H. et al. A novel model of integrated care for the elderly: COPA, Coordination of Professional Care for the Elderly. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research 2009;21:414–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kodner D, Spreeuwenberg C. Integrated care: meaning, logic, applications and implications – a discussion paper. International Journal of Integrated Care 2002;2:e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shortell SM. Increasing value: a research agenda for addressing the managerial and organizational challenges facing health care delivery in the United States. Medical Care Research and Review 2004;61(3 Suppl):12S–30S. 10.1177/1077558704266768 [published OnlineFirst: Epub Date]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shortell SM, Gillies RR, Anderson DA. et al. Creating organized delivery systems: the barriers and facilitators. Hospital and Health Services Administration 1993;38(4):447–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kodner D. All together now: a conceptual exploration of integrated care. Healthcare Quarterly 2009;13(Sp):6–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breton M, Pineault R, Levesque JF. et al. Reforming healthcare systems on a locally integrated basis: is there a potential for increasing collaborations in primary healthcare? BMC Health Services Research 2013;13:262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levesque JF, Pineault R, Provost S. et al. Assessing the evolution of primary healthcare organizations and their performance (2005–2010) in two regions of Québec province: Montréal and Montérégie. BMC Family Practice 2010;11:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrington WD, Wilson K, Rosenberg M. et al. Access granted! Barriers endure: determinants of difficulties accessing specialist care when required in Ontario, Canada. BMC Health Services Research 2013;13:146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Commissaire à la santé et au bien-être. Améliorer l'accès aux services de première ligne et aux soins spécialisés. Info-performance 2012;5. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ménard D. Bilan et perspectives de l'accueil clinique: évaluation du programme de l'accueil clinique 2005–2010. CSSS du Sud de Lanaudière: St Jérome, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boucher G. Accueil Clinique: un trait d'union web au bénéfice de la clientèle. Synergie-AQESSS 2011;10. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pigeon É, Larocque I. Tendances temporelles de la prévalence et de l'incidence du diabète, et mortalité chez les diabétiques au Québec, de 2000–2001 à 2006–2007. Gouvernement du Québec, Ministeres des Communications: Queébec, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Breton M, Lamothe L, Denis JL. How healthcare organizations can act as institutional entrepreneurs in a context of change. Journal of Health Organization and Management 2014;28(1):77–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centre de santé et services sociaux du Sud-ouest Verdun. Programme clinique du Centre de référence sur le diabète. Montréal: CSSS du Sud-Ouest Verdun; http://www.sov.qc.ca/fileadmin/csss_sov/Menu_du_haut/Publications/Programme_clinique/pc_diabete.pdf 2008. (accessed XX/XX/XX). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Commissaire à la santé et au bien-être. L'expérience de soins de la population: le québec comparé. Résultats de l'enquête internationale du Commonwealth fund de 2010 auprès de la population 18 ans+. Commissaire à la santé et au bien-être: Québec, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breton M, Gagne J, Fortune G. Implementing centralized waiting lists for patients without a family physician in Québec. Health Reform Observer 2014;2:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breton M, Ricard J, Walter N. Connecting orphan patients with family physicians: Differences among Québec's access registries. Canadian Family Physician 2012;58:921–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Commissaire à la santé et au bien-être. Perceptions et expériences des médecins de première ligne: le québeccomparé. Résultats de l'enquête internationale sur les politiques de santé du Commonwealth Fund de 2012. Commissaire à la santé et au bien-être: Québec, 2013. [Google Scholar]