Abstract

Purpose

TrkB acts as an oncogenic kinase in a subset of human neuroblastomas. Lestaurtinib, a multi-kinase inhibitor with potent activity against Trk kinases, has demonstrated activity in preclinical models of neuroblastoma.

Methods

Patients with refractory high-risk neuroblastoma received lestaurtinib twice daily for 5 days out of seven in 28-day cycles, starting at 70% of the adult recommended Phase 2 dose. Lestaurtinib dose was escalated using a 3 + 3 design. Pharmacokinetics and plasma phospho-TrkB inhibitory activity were evaluated in the first cycle.

Results

Forty-seven subjects were enrolled, and 10 dose levels explored starting at 25 mg/M2/dose BID. Forty-six subjects were evaluable for response, and 42 subjects were fully evaluable for determination of dose escalation. Asymptomatic and reversible grade 3–4 transaminase elevation was dose limiting in 4 subjects. Reversible pancreatitis (grade 2) was observed in 3 subjects after prolonged treatment at higher dose levels. Other toxicities were mild and reversible. Pharmacokinetic analyses revealed rapid drug absorption, however inter-patient variability was large. Plasma inhibition of phospho-TrkB activity was observed 1 h post-dosing at 85 mg/M2 with uniform inhibition at 120 mg/M2. There were two partial responses and nine subjects had prolonged stable disease at dose levels ≥ 5, (median: 6 cycles). A biologically effective and recommended phase 2 dose of 120 mg/M2/dose BID was established.

Conclusions

Lestaurtinib was well tolerated in patients with refractory neuroblastoma, and a dose level sufficient to inhibit TrkB activity was established. Safety and signs of activity at the higher dose levels warrant further evaluation in neuroblastoma.

Keywords: Neuroblastoma, Receptor tyrosine kinase, Targeted therapy, Lestaurtinib, Signal transduction

Introduction

Neuroblastoma, a pediatric malignancy of the sympathetic nervous system, is characterized by clinical and biological heterogeneity. Approximately one-half of neuroblastoma patients present with advanced-stage disease, and despite intensive multimodality therapy, including myeloablative regimens, survival for these children is less than 40% [9, 13, 16]. Identification of tumor targets and advances in target-specific therapies with minimal non-specific toxicity are needed for this patient population.

The Trk family of receptor tyrosine kinases is critical for neuronal survival and differentiation during the development of the nervous system. The Trk receptors are differentially expressed in human neuroblastoma and likely play a central role in tumorigenesis and/or cell survival [3–5, 18]. TrkA is highly expressed by neuroblastomas with favorable biological and clinical features, and expression is associated with patient outcome [3, 5, 19, 26]. In contrast, TrkB expression is restricted to a malignant subset of neuroblastomas [3, 20]. Co-expression of TrkB and its ligand, BDNF, in the majority of neuroblastomas, provides a potential autocrine survival pathway in biologically aggressive, high-risk tumors [1, 3, 15]. Additionally, the recent identification of a constitutively active TrkA splice variant (TrkAIII) that is preferentially expressed in advanced-staged tumors highlights the complex role of Trk signaling in neuroblastoma biology and its potential as a therapeutic target [23, 24].

Lestaurtinib (CEP-701; Cephalon, Inc.) is an oral indolocarbazole compound that is a small-molecule inhibitor of several receptor tyrosine kinases, and it competitively inhibits ATP binding to the Trk kinase domain at nanomolar concentrations. [17]. Pharmacologic inhibition of the TrkB/BDNF pathway has demonstrated activity in pre-clinical models of human neuroblastoma, with tumor growth inhibition and improvement in event free survival in mice bearing TrkB over-expressing xenograft neuroblastomas [7, 8, 10]. Treatment with lestaurtinib in combination with single- or multi-agent chemotherapy regimens demonstrate enhanced inhibition of tumor growth and improved event-free survival (EFS), suggesting particular effectiveness of TrkB inhibition in combination with conventional cytotoxic agents [10].

In phase I trials of lestaurtinib in adult subjects, the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) and optimum biological dose was considered between 40 and 80 mg BID, and 60 mg PO BID was recommended for further study [14, 22]. A recent phase II trial of lestaurtinib in 22 patients with relapsed or refractory JAK2-mutated (JAK2V617F) myelofibrosis demonstrated an overall response rate of 27%, with a median duration of 14 months [21]. Here we report a phase I trial of lestaurtinib in patients with relapsed or refractory high-risk neuroblastoma.

Patients and methods

Eligibility

Eligible patients had high-risk neuroblastoma ≤ 30 years of age at diagnosis, with disease that was recurrent or refractory to standard therapy. All subjects were required to have measurable or evaluable tumor on computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scan, and/or bone marrow morphology. Subjects with only marrow disease required a positive evaluation on two successive examinations (1 day to 4 weeks apart). Other eligibility criteria included Karnofsky/Lansky performance status ≥ 50%, hemoglobin ≥ 8 g/dL, absolute neutrophil count ≥ 1,000/μL, platelet count ≥ 50,000/μL, adequate renal and hepatic function, and life expectancy > 2 months. Subjects with neuroblastoma metastatic to bone marrow not meeting hematologic entry criteria, were eligible for study entry if all other criteria were met, but not evaluable for hematologic toxicity. Prior autologous stem-cell transplantation was allowed. The initial hepatic eligibility criteria for AST/ALT were ≤5.0X upper limit of normal (ULN), but this was subsequently changed to normal liver function because of asymptomatic hepatic dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) in two subjects and minor liver function test (LFT) elevation in 5/12 subjects. No hepatic toxicity was observed, and criteria were relaxed to AST/ALT ≤ 3.0X ULN. The protocol was sponsored by the New Approaches to Neuroblastoma Therapy (NANT) consortium (www.nant.org), and was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. Local institutional review board approval and informed consent was obtained for all patients.

Study design

This was an open label phase I trial of oral lestaurtinib. The starting dose of lestaurtinib was 25 mg/M2/dose given twice daily for five consecutive days (days 1–5) followed by a two-day rest, for 28 days; one treatment cycle equaled 28 days. Toxicity was graded according to National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria version 3.0. Hematologic DLT was defined as grade 4 neutropenia for more than 7 days, platelets less than 10,000/μL on one or more occasion during cycle 1, or failure to recover a neutrophil count to ≥500/μL or a platelet count to ≥20,000/μL by day 35 of cycle 1. Non-hematologic DLT included any grade 3 or 4 toxicity, excluding grade 3 nausea or vomiting recovering to grade ≤ 1 within 7 days of holding lestaurtinib, (≥75% of cycle 1 drug must be given to remain evaluable), grade 3 nausea or vomiting successfully treated with antiemetics, grade 3 elevations in ALT or AST recovering to grade ≤ 1 or baseline level by day 35 of treatment cycle (7 days off drug and delay in start of next cycle), or grade 3 fever or infection, which recovered to grade ≤ 1 by day 35 of treatment cycle.

Subjects were evaluable for toxicity on day 28 of cycle 1 or sooner if DLT occurred (with the exception of missing ≤ 25% of planned treatment due to grade 3 nausea or vomiting, all evaluable patients were required to receive the full planned treatment). Decisions to dose escalate, expand or de-escalate were based on DLT observed during cycle 1 that were possibly, probably, or definitely attributed to lestaurtinib. Subsequent treatment cycles were repeated immediately, provided that all toxicities resolved to ≤grade 1 or to baseline toxicity if ≥grade 1 and there was no disease progression. Subjects whose toxicities did not recover by day 28 of any given cycle had drug held until criteria were met. If drug was held beyond day 35 to meet starting criteria, then dose was reduced by 25%. Subjects requiring dose reductions on more than two occasions were removed from therapy.

Lestaurtinib doses were escalated using standard 3 + 3 phase I design (Table 1); initially, the dose was increased in 30% increments through dose level 5. The study was amended to require normal LFTs at entry and dose escalation narrowed to 15% increments due to concern for hepatotoxicity. However, no significant hepatic toxicities were observed, so LFT criteria were liberalized and dose escalation was returned to 30% to complete ten dose levels.

Table 1.

Dose escalation schema

| Dose level | Dose of lestaurtinib (mg/M2/dose BID) | Subjects entered (# subjects with DLT during course 1) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25 | 3 |

| 2 | 35 | 3 |

| 3 | 45 | 3 |

| 4 | 55 | 7 (1) |

| 4a | 62.5 | 5 |

| 5 | 70 | 10 (2) |

| 5a | 77.5 | 4 |

| 6 | 85 | 3 |

| 7 | 92.5 | 3 |

| 8 | 120 | 6 (1) |

Tumor response

Tumor response was evaluated after cycles 1, 2, 4, 8, and after every 4th subsequent cycle while subjects continued to receive lestaurtinib. Overall response was assigned using NANT response criteria, incorporating a modification of the International Neuroblastoma Response Criteria [6], using the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) method for measurable tumor on CT/MRI scans [25] and Curie score for grading the response of MIBG lesions [2]. A complete bone marrow response required no tumor cells detected by morphology on two consecutive bilateral bone marrow aspirates and biopsies performed at least 3 weeks apart. CT/MRI/MIBG scans and bone marrow slides were centrally reviewed for subjects with reported SD ≥ 4 cycles or partial responses (PR) by treating site.

Pharmacokinetics

Serial venous blood samples for the determination of plasma lestaurtinib concentrations were collected prior to the morning dose and 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h after the morning dose of lestaurtinib on day 1 of cycle 1. Additional pre-dose blood samples were drawn on days 5 and 26 of cycle 1 for the assessment of trough plasma concentrations.

Plasma samples were analyzed for concentrations of lestaurtinib using a validated high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method. The method utilized liquid–liquid extraction of lestaurtinib and an internal standard (KT-252a) from 0.1 mL of human plasma into a mixture of ethyl acetate:methylene chloride 4:1 (v/v) followed by reversed-phase chromatography on a Hypersil® BDS phenyl column (2.1 × 150 mm; 5 μ particle size) [Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA] maintained at 35°C. Chromatography was isocratic, with a mobile phase consisting of a 70:30 (v/v) mixture of water:acetonitrile. The eluate was monitored by fluorescence detection with an excitation wavelength of 303 nm and an emission wavelength of 403 nm. Quantification was based on a 1/(x2)-weighted linear regression analysis of the peak height ratios of lestaurtinib to the internal standard versus nominal concentration, from extracted human plasma calibration standards. The quantifiable range of the assay was from 5.00 to 1,000 ng/mL of human plasma.

Pharmacokinetic parameters for lestaurtinib, including the observed maximal plasma concentration (Cmax), the time to Cmax (tmax), the area under the plasma concentration–time curve from time zero to infinity (AUC∞), terminal elimination half-life (t½), apparent clearance (CL/F), and apparent volume of distribution (V/F) were estimated by standard non-compartmental methods. Trough plasma concentrations (Ctrough) were determined from the predose samples obtained on day 5 and day 26.

Pharmacodynamic assay/plasma inhibitory activity

To permit assessment of target modulation by free drug in plasma, blood samples were collected before, and 1 h after lestaurtinib administration, on days 1, 5, and 26 of cycle 1 and processed for plasma inhibitory activity assays as described for FLT3 [12]. We used a Trk-null neuroblastoma cell line (SH-SY5Y) stably transfected with full-length TrkB that showed robust TrkB phosphorylation in response to exogenous BDNF. For each time point, SY5Y-TrkB cells were incubated with diluted (75% v/v) plasma at 37°C for 2 h, then treated with BDNF (100 ng/mL) for 30 min. Pre-treatment plasma was used as a baseline for phosphorylated TrkB. The plasma treated SY5Y-TrkB cells were collected in cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), and analyzed for levels of TrkB phosphorylation by anti-phosphotyrosine immunoblotting. Blots were stripped and re-probed with anti-total Trk antibody for normalization of phospho-Trk bands (phospho-TrkB/total-TrkB). Controls included untreated cells, cells treated with control (non-patient) plasma, and cells treated with 100 nM exogenous Lestaurtinib. The parental SY5Y cell line used to generate the TrkB expressing cell line is maintained in the laboratory of GMB. The cell line was an early passage (p6) cell line confirmed by morphology and DNA fingerprinting to be SY5Y. All cell lines were tested for mycoplasma prior to use in the pharmacodynamic (pD) assay.

Immunoblots were quantified by densitometry. The plasma inhibitory activity for a given sample was calculated on the normalized samples by expressing the ratio of density of the normalized phospho-TrkB band 1 h post-lestaurtinib as a percent decrease from the density of the pre-lestaurtinib band, which was arbitrarily set at 100%.

Results

Patient characteristics

Forty-seven subjects were enrolled onto the study with a median age of 10.7 years (range 3.5–29.1) at study entry. Forty-six subjects were evaluable for response. One subject entered with tumor reported on MIBG scan that was not confirmed on central review. Forty-two subjects were evaluable for dose escalation; four subjects were not evaluable due to early disease progression during cycle 1, and one subject missed > 10% of drug doses during the first cycle, due to loss of drug (not gastrointestinal toxicity). Subjects entered the study with a median of 5 prior treatment regimens (range 2–11). Twenty-four subjects had measurable soft tissue lesions, 42 had 123I-MIBG avid disease, and 22 had disease metastatic to the bone marrow at study entry.

Toxicity

Toxicities reported to be possibly attributable to lestaurtinib are summarized in Table 2. Lestaurtinib was generally well tolerated at all dose levels, and no MTD was defined. Non-hematologic DLTs were identified at dose level 5 (70 mg/M2/dose) in two subjects with asymptomatic elevated transaminase levels (grade 2 AST, grade 3 ALT) that did not resolve by day 35. Neither of these subjects demonstrated clinical evidence of liver disease or other adverse effects, and the LFT abnormalities were identified on routine laboratory testing. Both subjects had baseline grade 2 ALT elevation at study entry, likely related to prior therapies, as metastatic neuroblastoma involvement of the liver was not detected. One of these subjects was removed from the study for persistent ALT elevation. A review of the first four dose levels demonstrated that 33% (4/12) of subjects experienced minor changes in LFTs following lestaurtinib therapy. Since adult lestaurtinib clinical trial data did not demonstrate hepatic toxicity after prolonged drug exposure (≥12 weeks of daily dosing), the study was modified to require normal LFTs for study entry, de-escalation and expansion of dose level 4, and to decrease the increment of dose escalation from 30 to 15%. Two additional subjects on the amended protocol experienced hepatic DLT with asymptomatic transaminase elevation, one subject at the expanded dose level 4 (grade 4 ALT) and one subject at dose level 8 (persistent grade 3 AST). The subject at dose level 8 had measurable disease involving the liver at study entry, which may have contributed to hepatic DLT during treatment. Both subjects had resolution of transaminase elevation when lestaurtinib was held and restarted at a reduced dose.

Table 2.

Episodes of grade 3 or 4 toxicities possibly attributable to lestaurtinib

| Dose level (mg/M2/dose) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 35 | 45 | 55 | 62.5 | 70 | 77.5 | 85 | 92.5 | 120 | |

| (# Subjects) | (3) | (3) | (3) | (7) | (5) | (10) | (4) | (3) | (3) | (6) |

| (# Total courses) | (7) | (7) | (9) | (11) | (9) | (40) | (61) | (5) | (28) | (27) |

| Toxicity | ||||||||||

| Neutropeniaa | 2b | 2b | ||||||||

| Hepatic (ALT) | 1 | 6c | 1 | |||||||

| Hepatic (AST) | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Metabolic/laboratory (Lipase) | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Metabolic/laboratory (Amylase) | 1d | 1d | 1 | |||||||

Subjects did not have bone marrow involvement at baseline

One patient at that dose level

6 episodes in 3 patients

2 episodes in 1 patient after dose reduction

Three subjects developed pancreatitis after prolonged drug exposure. One subject at dose level 5 developed grade 3 abdominal pain and grade 4 lipase elevation after cycle 13 that resolved with discontinuation of lestaurtinib. The second subject, at dose level 8, developed grade 2 pancreatitis with grade 4 amylase and lipase elevation after cycle 5 that all resolved with discontinuation of lestaurtinib. The third developed mild abdominal pain and grade 3 amylase elevation after cycle 14 at dose level 7. This subject had a dose-reduction to level 6 and remained with persistent grade 2 amylase elevation without clinical symptoms of pancreatitis. Asymptomatic recurrence of grade 3 amylase occurred after cycle 25, and a second dose-reduction to level 5 occurred for cycle 26. The subject remains on therapy with no clinical symptoms of pancreatitis. These three episodes were considered possibly related to prolonged treatment with lestaurtinib.

There were no hematologic DLTs identified, two subjects without disease involving the bone marrow experienced grade 3 hematologic toxicities possibly related to lestaurtinib. This did not appear dose-related, since toxicity occurred at dose levels 3 and 8.

Two second malignancies were reported in subjects who had multiple other prior therapies: AML 5 months after 2 cycles at dose level 4, and high-grade undifferentiated sarcoma of brain in a subject who received 13 cycles at dose level 5.

Pharmacokinetics

Pharmacokinetic analyses indicate that orally administered lestaurtinib was rapidly absorbed in children (median tmax 1.0–2.0 h across dose levels), as it is in adults (Table 3). In adult patients, the increase in Cmax and AUC are largely dose-proportional after single-dose administration from 5 to 80 mg and more than dose-proportional in this range after multiple-dose administration, though variability is increased at the higher dose levels (19). In this study, in which higher doses were explored in a broad range of ages, systemic exposure (i.e, Cmax and AUC on day 1 and Ctrough on days 5 and 26) did not consistently increase with increasing dose and not unexpectedly, inter-patient variability was large (Tables 3, 4). In comparison to adult patients, systemic exposure (AUC) was approximately 50% lower in children at a dose of lestaurtinib that was comparable to the highest dose in adults (on a mg/M2 basis). Conversely, systemic exposures were higher in children than adults at smaller comparable dose levels [14].

Table 3.

Mean ± SD pharmacokinetic parameters of lestaurtinib in patients with refractory neuroblastoma administered single oral doses of lestaurtinib on day 1 of course 1

| Dose (mg/m2 BID) | Day 1

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmax (ng/mL) | (h) | AUC0–t (ng•h/mL) | AUC0–∞ (ng•h/mL) | t1/2 (h) | |

| 25 (n = 3) | 2,396.9 ± 966.1 | 1.5 [1.5–6.0] | 29,475 ± 17,131 | 39,538 ± 25,364 | 10.5 ± 3.6 |

| 35 (n = 2) | 3,391.4 | 2.0 [1.0, 3.0] | 37,509 | 41,342 | 7.0 |

| 45 (n = 3) | 3,061.1 ± 2,394.7 | 1.0 [1.0–3.0] | 15,937 ± 7,609 | 16,375 ± 7,966 | 4.5 ± 1.2 |

| 55 (n = 4) | 4,902.3 ± 2,450.2 | 1.0 [0.5–2.0] | 34,907 ± 35,422 | 40,815 ± 45,349 | 6.0 ± 3.4 |

| 62.5 (n = 4) | 4,496.3 ± 1,096.6 | 1.0 [1.0–1.5] | 26,604 ± 17,684 | 28,916 ± 18,435 | 4.3 ± 0.9 |

| 70 (n = 5) | 3,812.4 ± 964.5 | 1.0 [1.0–1.5] | 15,011 ± 6,682 | 15,773 ± 6,883 | 3.6 ± 1.4 |

| 77.5 (n = 1) | 3,677.0 | 2.0 | 47,501 | 54,826 | 8.2 |

| 85 (n = 2) | 3,455.0 | 1.0 [1.0, 1.0] | 15,483 | 15,634 | 3.9 |

| 92.5 (n = 1) | 8,735.1 | 1.0 | 37,104 | 51,458 | 4.3 |

| 120 (n = 2) | 3,513.9 | 1.5 [1.0, 2.0] | 34,938 | 39,509 | 7.9 |

Patients were administered a single oral dose of lestaurtinib on day 1 of course 1 and then twice-daily oral doses of lestaurtinib on days 2–5, 8–12, 15–19 and 22–26

Median [range]

Table 4.

Mean ± SD trough plasma concentrations of lestaurtinib in patients with refractory neuroblastoma on days 5 and 26 of twice-daily administration of lestaurtinib during course 1

| Dose (mg/m2 BID) | Day 5 Ctrough (ng/mL) |

Day 26 Ctrough (ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| 25 (n = 3) | 3,365.6 ± 2,878.1 | 4,168.2 ± 3,612.4 |

| 35 (n = 2) | 1,854.6 | 6,132.3 |

| 45 (n = 3) | 984.6 ± 519.2 | 829.8a |

| 55 (n = 5) | 1,647.2a | 3,041.2 ± 3,891.4 |

| 62.5 (n = 4) | 1,226.3 ± 778.4b | 1,407.0c |

| 70 (n = 5) | 1,063.1 ± 700.9 | 3,054.1 ± 604.2b |

| 77.5 (n = 1) | 3,540.4 | 5,532.6 |

| 85 (n = 2) | 1,572.6 | 3,853.4 |

| 92.5 (n = 1) | 3,658.7 | NS |

| 120 (n = 2) | 2,451.7 | 5,556.6 |

Patients were administered a single oral dose of lestaurtinib on day 1 of course 1 and then twice-daily oral doses of lestaurtinib on days 2–5, 8–12, 15–19 and 22–26

NS No sample

n = 2

n = 3

n = 1

Pharmacodynamic phospho-TrkB analysis

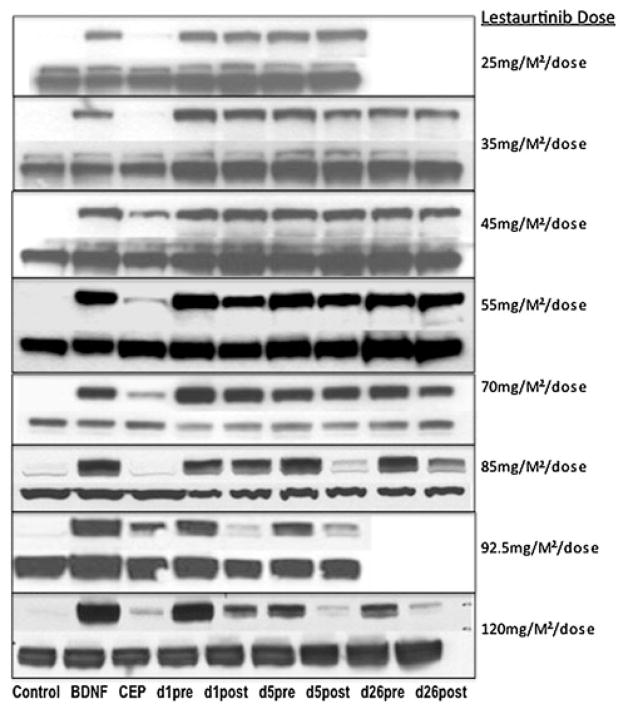

Pharmacodynamic studies were conducted in 31 subjects across all ten dose levels. Inhibition of phosphorylation of TrkB by immunoblotting was evident only in cells exposed to plasma from subjects treated at dose levels ≥ 6 (≥85 mg/M2/dose) (Fig. 1). At these higher doses, kinase inhibition was detected in the ex vivo assay in samples obtained on days 5 and 26. The average decrease in TrkB phosphorylation of all subjects with pharmacodynamic samples from day 5 pre/post lestaurtinib was calculated and plotted by dose level (Fig. 2). Sustained suppression of TrkB phosphorylation, by twice daily dosing of lestaurtinib, was not evident, as the pre-drug/trough plasma samples did not show inhibition of TrkB phosphorylation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Phospho-TrkB inhibition by subject plasma after lestaurtinib. Immunoblotting with anti-phospho-TrkB demonstrates post-dose decreases in phospho-TrkB are achieved at dose level ≥ 6 on days 5 and 26 in representative plasma samples. Samples from subjects at dose levels 25 mg/M2/dose and 92.5 mg/M2/dose from day 26 were unavailable or inadequate for this assay. Controls lanes: no treatment, BDNF only, BDNF plus lestaurtinib (300 nM). The lower lane of bands at each dose level is the matched total-TrkB control from each patient

Fig. 2.

Day 5 plasma inhibitory activity of lestaurtinib. Plasma inhibitory activity (displayed as percent change in TrkB phosphorylation on y-axis) for phospho-TrkB is plotted against the lestaurtinib dose level (x-axis). The level of phospho TrkB inhibition for each subject within a dose level is indicated by black diamonds, and the mean value of the change in TrkB phosphorylation from day 5 (pre/post lestaurtinib) for all subjects within a dose level is indicated by open red squares. The open red squares are the changes in TrkB phosphorylation on day 5 pre/post-lestaurtinib plasma samples, calculated from quantitative densitometry of immunoblots

Antitumor activity

A total of 204 cycles of therapy over ten dose levels of lestaurtinib were given, with a median of 2 cycles per subject and a range of 1–28 cycles. Forty-two subjects came off study for progressive disease (PD); three for toxicity, and one patient withdrew consent after 3 cycles. One subject remains on therapy, on cycle 26 at the time of this report.

Forty-six subjects were assessable for response. Two subjects had partial responses (PR); one subject with PR entered the study with bone marrow involvement and bone disease and had complete resolution of bone marrow disease (confirmed by review of reports, but material for central review were inadequate to confirm), and PR in cortical bony lesions (confirmed on central review). This overall PR was maintained through 18 cycles of treatment (Table 5). This subject had no change in urine catecholamines. The second subject with PR entered with bone lesions and had PR after cycle 8 (Curie score = 4), improving by cycle 16 (Curie score = 2), and maintained through cycle 28. This subject had a urine catecholamine response of 15% reduction in HVA and 44% reduction in VMA.

Table 5.

Response to lestaurtinib (N = 46)

| Best overall responses | |

| PR | 2/46 |

| Mixed | 3/46 |

| Stable disease | 20/46 |

| Progressive disease | 21/46 |

| Number of treatment courses prior to PD | |

| 4–10 months | 11a/46 |

| 11–16 months | 3b/46 |

| ≥17 months | 3/46 |

| Dose levels of response/SD > 5 months | |

| Dose level 1–3 | 0/9 (total subjects at dose levels 1–3) |

| Dose level 4–5c | 2/22 (2 SD) |

| Dose level 5a–8d | 8/16 (2 PR, 2 Mixed, 4 SD) |

Complete response (CR), Partial response (PR), Stable disease (SD)

One of 11 patients stopped therapy after 5 cycles due to toxicity

One of 3 patients stopped therapy after 13 cycles due to toxicity

Cohorts expanded, dose de-escalated then re-escalated for toxicity monitoring

Modified dose escalation (level 5–5a increased by 15%)

Three subjects had mixed responses. The subject still on therapy (course 27) had >90% reduction in measurable tumor (CT), marked decrease in urine catecholamines (48% reduction in HVA, 65% reduction in VMA), and stable MIBG scan. The other subjects with mixed responses had complete marrow responses and stable MIBG scans after cycle 2, subsequently progressing after cycles 4 and 5. These subjects also had substantial decrease in urine catecholamines (98% reduction in HVA and VMA in one subject; 15% reduction in HVA/45% reduction in VMA in the other subject). Six subjects had prolonged stable disease for a median of 7 cycles (range 5–13); one subject decreased marrow tumor content from 75 to 2%. Among 26 subjects treated at dose levels > 5, 10 (38.5%) maintained a response or SD for at least 5 cycles; and at dose levels ≥ 5a, 8/16 (50%) patients maintained a response or SD for a median of 10 months. The small number of subjects with full sets of samples for pharmacodynamic analyses precludes an analysis of correlations between plasma inhibitory activity results and clinical results.

Discussion

This study accrued a large number of subjects, and we have explored 10 dose levels, greatly exceeding the anticipated MTD of 60 mg BID identified in adult trials. Oral lestaurtinib was well tolerated using a twice daily, five-day on/two-day off schedule of administration, despite highly variable drug metabolism and clearance. No MTD was defined for lestaurtinib in pediatric patients on this trial, but a potentially biologically effective dose of 120 mg/M2/dose BID is recommended based on prolonged disease control at dose levels ≥ 5 and an ex vivo plasma inhibitory activity assay that demonstrated consistent target inhibition above dose level 5 at 1 h post-drug. We did not see sustained target inhibition, as trough plasma samples did not demonstrate significant inhibition of TrkB phosphorylation, but it is unclear if sustained inhibition of TrkB activation is important clinically.

Lestaurtinib was well tolerated in this heavily pre-treated population, and reported toxicities were generally mild to moderate. Unlike previous trials of lestaurtinib that used continuous dosing schedules, we elected to use a 5 day on/2 day off schedule of administration to facilitate collection of pK and pD samples, and speculate that the two-day drug holidays each week may have improved tolerability of drug and allowed for extended dose escalations and prolonged treatment. Because most refractory neuroblastoma patients have metastatic tumor to bone marrow, and/or significant marrow stromal damage from prior myeloablative chemotherapy, agents with limited impact on the hematologic compartment are of interest. Non-cytotoxic agents are also desired if the ultimate goal is to integrate these targeted agents into regimens containing chemotherapy or radiotherapy. The most common non-hematologic toxicity was transaminase elevation that was grade 1/2 in 30 subjects (64%), and grade 3/4 or dose limiting in 5 subjects (11%). Hepatic toxicity has not been described as a dose limiting toxicity in previous trials of lestaurtinib [11, 14, 21, 22]; rather only grade 1/2 elevated LFTs possibly related to lestaurtinib have been described in 30% or fewer patients [11, 21]. The majority of patients with refractory, high-risk neuroblastoma had undergone high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplant as prior therapy, and some had liver involvement of disease, both of which may predispose subjects on this trial to hepatoxicity unrelated to lestaurtinib. We observed grade 2 pancreatitis in three subjects only after prolonged exposure to lestaurtinib (5–14 cycles), at higher dose levels (5, 7, 8). Although this toxicity has not been previously reported for lestaurtinib, only one trial reported subjects with prolonged exposure to drug (>14 months), and the dose was significantly below dose levels achieved here [21].

Although assessment of antitumor efficacy is limited here, clinical benefit associated with lestaurtinib at higher doses suggests potential activity. Prolonged control of disease for a median of 10 cycles (range 5–28) was seen in 10 (38.5%) of 26 subjects at doses ≥ 70 mg/M2/dose BID. Above this dose is also where we began to see consistent target inhibition (phospho-TrkB) in our pharmacodynamic bioassay. This is the first clinical trial to demonstrate a pharmacodynamic correlation between target inhibition (phospho-TrkB) by subject-derived plasma and clinical response to lestaurtinib. Although this assay reflects free drug activity only, it suggests that there may be a dose–response effect. The assay was not used to guide dose escalation in phase I, but there appears to be a dose response at plasma levels where disease stabilization was prolonged, and this might be useful as a surrogate marker for guiding dose finding in future trials.

While lestaurtinib is clearly a non-specific inhibitor of ATP binding for multiple kinases, it does inhibit the Trk family at low nanomolar concentrations, and this study does suggest that further consideration of TrkB-targeted therapy seems warranted. TrkB functions as an oncogenic driver in at least a subset of neuroblastomas, and its expression is associated with poor prognosis [3]. Our results here suggest that lestaurtinib has activity against refractory neuroblastoma, and that this is mediated, at least partially, through modulation of Trk signalling. Because this drug is well tolerated without hematologic toxicity in children, and it enhances the effect of camptothecin-containing regimens in preclinical models [10], it appears ideal for combination therapy. A phase 2 study of lestaurtinib to establish single agent activity and/or potential enhancement of conventional salvage chemotherapy activity should be pursued based on the data presented here.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Program Project Grants P01-CA81403 (Childrens Hospital Los Angeles, PI:Seeger) and P01-CA97323 (Brodeur), R01-CA-094194 (Brodeur), and the Giulio D’Angio Endowed Chair in Neuroblastoma Research (Maris), NIH/NCRR UCSF-CTSI Grant UL1 RR024131, Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation, Children’s Neuroblastoma Cancer Foundation, Dougherty Family Foundation, Evan T.J. Dunbar Memorial Foundation, Neuroblastoma Children’s Cancer Society.

Contributor Information

Jane E. Minturn, Department of Pediatrics and Center for Childhood Cancer Research, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Audrey E. Evans, Department of Pediatrics and Center for Childhood Cancer Research, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Judith G. Villablanca, Departments of Pediatrics and Biostatistics, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California and Childrens Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Gregory A. Yanik, University of Michigan and C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

Julie R. Park, Department of Pediatrics, Seattle Children’s Hospital and University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Suzanne Shusterman, Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital Boston and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA.

Susan Groshen, Departments of Pediatrics and Biostatistics, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California and Childrens Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Edward T. Hellriegel, Departments of Drug Safety and Disposition and Clinical Research, Oncology, Cephalon, Inc., Frazer, PA, USA

Debra Bensen-Kennedy, Departments of Drug Safety and Disposition and Clinical Research, Oncology, Cephalon, Inc., Frazer, PA, USA.

Katherine K. Matthay, Department of Pediatrics, University of California San Francisco School of Medicine, San Francisco, CA, USA

Garrett M. Brodeur, Email: brodeur@email.chop.edu, Department of Pediatrics and Center for Childhood Cancer Research, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA. Division of Oncology, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, 3501 Civic Center Blvd., CTRB 3018, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA

John M. Maris, Email: maris@chop.edu, Department of Pediatrics and Center for Childhood Cancer Research, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA. Division of Oncology, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, 3501 Civic Center Blvd., CTRB 3060, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA

References

- 1.Acheson A, Conover JC, Fandl JP, DeChiara TM, Russell M, Thadani A, Squinto SP, Yancopoulos GD, Lindsay RM. A BDNF autocrine loop in adult sensory neurons prevents cell death. Nature. 1995;374:450–453. doi: 10.1038/374450a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ady N, Zucker JM, Asselain B, Edeline V, Bonnin F, Michon J, Gongora R, Manil L. A new 123I-MIBG whole body scan scoring method–application to the prediction of the response of metastases to induction chemotherapy in stage IV neuroblastoma. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31A:256–261. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)00509-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asgharzadeh S, Pique-Regi R, Sposto R, Wang H, Yang Y, Shimada H, Matthay K, Buckley J, Ortega A, Seeger RC. Prognostic significance of gene expression profiles of metastatic neuroblastomas lacking MYCN gene amplification. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1193–1203. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brodeur GM, Maris JM, Yamashiro DJ, Hogarty MD, White PS. Biology and genetics of human neuroblastomas. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1997;19:93–101. doi: 10.1097/00043426-199703000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brodeur GM, Minturn JE, Ho R, Simpson AM, Iyer R, Varela CR, Light JE, Kolla V, Evans AE. Trk receptor expression and inhibition in neuroblastomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3244–3250. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brodeur GM, Pritchard J, Berthold F, Carlsen NL, Castel V, Castelberry RP, De Bernardi B, Evans AE, Favrot M, Hedborg F, et al. Revisions of the international criteria for neuroblastoma diagnosis, staging, and response to treatment. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:1466–1477. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.8.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans AE, Kisselbach KD, Liu X, Eggert A, Ikegaki N, Camoratto AM, Dionne C, Brodeur GM. Effect of CEP-751 (KT-6587) on neuroblastoma xenografts expressing TrkB. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2001;36:181–184. doi: 10.1002/1096-911X(20010101)36:1<181::AID-MPO1043>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans AE, Kisselbach KD, Yamashiro DJ, Ikegaki N, Camoratto AM, Dionne CA, Brodeur GM. Antitumor activity of CEP-751 (KT-6587) on human neuroblastoma and medulloblastoma xenografts. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:3594–3602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.George RE, Li S, Medeiros-Nancarrow C, Neuberg D, Marcus K, Shamberger RC, Pulsipher M, Grupp SA, Diller L. High-risk neuroblastoma treated with tandem autologous peripheral-blood stem cell-supported transplantation: long-term survival update. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2891–2896. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.6986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iyer R, Evans AE, Qi X, Ho R, Minturn JE, Zhao H, Balamuth N, Maris JM, Brodeur GM. Lestaurtinib enhances the anti-tumor efficacy of chemotherapy in murine xenograft models of neuroblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1478–1485. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knapper S, Burnett AK, Littlewood T, Kell WJ, Agrawal S, Chopra R, Clark R, Levis MJ, Small D. A phase 2 trial of the FLT3 inhibitor lestaurtinib (CEP701) as first-line treatment for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia not considered fit for intensive chemotherapy. Blood. 2006;108:3262–3270. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-015560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levis M, Brown P, Smith BD, Stine A, Pham R, Stone R, Deangelo D, Galinsky I, Giles F, Estey E, Kantarjian H, Cohen P, Wang Y, Roesel J, Karp JE, Small D. Plasma inhibitory activity (PIA): a pharmacodynamic assay reveals insights into the basis for cytotoxic response to FLT3 inhibitors. Blood. 2006;108:3477–3483. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-015743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maris JM, Hogarty MD, Bagatell R, Cohn SL. Neuroblastoma. Lancet. 2007;369:2106–2120. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60983-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marshall JL, Kindler H, Deeken J, Bhargava P, Vogelzang NJ, Rizvi N, Luhtala T, Boylan S, Dordal M, Robertson P, Hawkins MJ, Ratain MJ. Phase I trial of orally administered CEP-701, a novel neurotrophin receptor-linked tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Invest New Drugs. 2005;23:31–37. doi: 10.1023/B:DRUG.0000047103.64335.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsumoto K, Wada RK, Yamashiro JM, Kaplan DR, Thiele CJ. Expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and p145TrkB affects survival, differentiation, and invasiveness of human neuroblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1798–1806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matthay KK, Villablanca JG, Seeger RC, Stram DO, Harris RE, Ramsay NK, Swift P, Shimada H, Black CT, Brodeur GM, Gerbing RB, Reynolds CP. Treatment of high-risk neuroblastoma with intensive chemotherapy, radiotherapy, autologous bone marrow transplantation, and 13-cis-retinoic acid. Children’s Cancer Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1165–1173. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910143411601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miknyoczki SJ, Dionne CA, Klein-Szanto AJ, Ruggeri BA. The novel Trk receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor CEP-701 (KT-5555) exhibits antitumor efficacy against human pancreatic carcinoma (Panc1) xenograft growth and in vivo invasiveness. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;880:252–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakagawara A. Trk receptor tyrosine kinases: a bridge between cancer and neural development. Cancer Lett. 2001;169:107–114. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00530-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakagawara A, Arima-Nakagawara M, Scavarda NJ, Azar CG, Cantor AB, Brodeur GM. Association between high levels of expression of the TRK gene and favorable outcome in human neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:847–854. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199303253281205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakagawara A, Azar CG, Scavarda NJ, Brodeur GM. Expression and function of TRK-B and BDNF in human neuroblastomas. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:759–767. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santos FP, Kantarjian HM, Jain N, Manshouri T, Thomas DA, Garcia-Manero G, Kennedy D, Estrov Z, Cortes J, Verstovsek S. Phase II study of CEP-701, an orally available JAK2 inhibitor, in patients with primary or post polycythemia vera/essential thrombocythemia myelofibrosis. Blood. 2009;115:1131–1136. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-246363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith BD, Levis M, Beran M, Giles F, Kantarjian H, Berg K, Murphy KM, Dauses T, Allebach J, Small D. Single-agent CEP-701, a novel FLT3 inhibitor, shows biologic and clinical activity in patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2004;103:3669–3676. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tacconelli A, Farina AR, Cappabianca L, Desantis G, Tessitore A, Vetuschi A, Sferra R, Rucci N, Argenti B, Screpanti I, Gulino A, Mackay AR. TrkA alternative splicing: a regulated tumor-promoting switch in human neuroblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:347–360. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tacconelli A, Farina AR, Cappabianca L, Gulino A, Mackay AR. TrkAIII. A novel hypoxia-regulated alternative TrkA splice variant of potential physiological and pathological importance. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:8–9. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.1.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, Verweij J, Van Glabbeke M, van Oosterom AT, Christian MC, Gwyther SG. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thiele CJ, Li Z, McKee AE. On Trk–the TrkB signal transduction pathway is an increasingly important target in cancer biology. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5962–5967. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]