Abstract

This prospective longitudinal study examined predictors of parenting stress trajectories over time in a sample of 125 mothers and their preterm infants. Infant (multiple birth, gestational age, days hospitalized, and neonatal health risks) and maternal (socioeconomic, education, depressive symptoms, social support, and quality of interaction during infant feeding) characteristics were collected just prior to infant hospital discharge. Parenting stress and maternal interaction quality during play were measured at 4, 24, and 36 months corrected age. Hierarchical linear modeling was used to analyze infant and maternal characteristics as predictors of parenting stress scores and change over time. Results indicated significant variability across individuals in parenting stress at 4 months and in change trajectories. Mothers of multiples and infants with more medical risks and shorter hospitalization, and mothers with lower education and more depressive symptoms, reported more parenting stress at 4 months of age. Parenting stress decreased over time for mothers of multiples and for mothers with lower education more than for mothers of singletons or for mothers with higher educational levels. Changes in parenting stress scores over time were negatively associated with maternal behaviors during mother–infant interactions. Results are interpreted for their implications for preventive interventions.

Keywords: prematurity, parenting stress, mother–infant relationship, hierarchical linear models, maternal depression

Starting during pregnancy, parents face multiple stressors related to their child's development, and parents differ in their responses to these situations (Abidin, 1990). Whereas some parents cope with the challenges in an effective manner, other parents experience difficulty coping, including reactions that reflect displays of emotional intensity, reactivity, or emotional withdrawal, reflected in elevated parenting stress. The present study examined the development of parenting stress longitudinally during the first three years of the child's life in a sample of mothers with infants born preterm. The primary goals of the study were to examine predictors of parenting stress trajectories and the potential link between parenting stress and mother–child interaction quality.

Parenting stress is a well-established construct defined as the perceived discrepancy between the demands of parenting and the resources available to meet those demands (Abidin, 1995). The current literature suggests that experiencing particularly stressful situations or conditions may lead to an increase in this discrepancy and, consequently, to higher levels of parenting stress. For these reasons, the study of determinants of parenting stress and its implications for the parent–child relationship are rapidly expanding areas of research. Within Abidin's (1990) theorizing, different domains of parenting stress are identified. Parenting stress could be related to how the parent perceives the infant as stressful, due to infant characteristics. Parenting stress is also about how the parent perceives parenting as a stressful experience due, for example, to the possible limitations that being a parent has on a mother's or father's life. Both these paths influence the total level of stress experienced by the parent and, consequently, her or his ability to fulfill the parental role.

Researchers have found that the ways in which parents cope with stressful situations are associated with child development and parent–child relationship outcomes, supporting the transactional model of development. For example, high levels of parenting stress have been linked to less child competence (Cappa, Begle, Conger, Dumas, & Conger, 2011), more early childhood anxiety symptoms (Pahl, Barrett, & Gullo, 2012), and behavioral problems (Benzies, Harrison, & Magill Evans, 2004). At the same time, parenting stress has also been seen as a factor influencing parenting behavior and a determinant of dysfunctional parenting (Webster-Stratton, 1990). For these reasons, the study of parenting stress and of changes in parenting stress over time, especially under potentially stressful conditions (Thomas, Renaud, & DePaul, 2004), has become a current research focus.

According to the transactional model of development, child and parent characteristics and interaction develop over time as a result of mutual influences between the child and the parent (Sameroff, 2009). Parenting stress can thereby be considered a complex phenomenon that is the result not only of the situation itself but also of the complex interplay among the parent, the child, and the situation (Abidin, 1990). Each of these factors could influence the parent–child relationship and could lead to different levels of parenting stress. According to this model, recent studies focusing on parenting stress have analyzed both child and maternal factors that might affect the development of the parent–child relationship under potentially stressful situations (Östberg & Hagekull, 2000; Williford, Calkins, & Keane, 2007).

Situated within the transactional developmental model, this study aimed to analyze infant and maternal predictors of early parenting stress, and of parenting stress trajectories of mothers of children born preterm, longitudinally over the first three years of the child's life. In addition, we explored how parenting stress covaried with the quality of maternal interactions with their children over time.

Parenting Stress and Prematurity

Prematurity and the neonatal complications associated with it are identified as risk factors that may bring psychological complications for the baby's development and for the early mother–infant relationship (Aarnoudse-Moens, Weisglas-Kuperus, van Goudo-ever, & Oosterlaan, 2009). The birth of a preterm infant, the sudden end of pregnancy, and the infant's medical complications and illness often represent stressful experiences for parents. Even though some neonatal problems may be viewed as temporary, parent–infant dyads who began their relationships under stressful circumstances may continue to experience greater interactive difficulty than those who did not experience this difficult beginning (Muller-Nix et al., 2004). Premature birth may affect parental perceptions and attitudes, thereby distorting normal parent–child interactions and relationships (Poehlmann, Schwichtenberg, Bolt, et al., 2011).

Very early interactions between mothers and their preterm infants occur in the atypical environment of the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), where, facing the possibility of the infant's morbidity or even mortality, parents may experience emotional exhaustion and helplessness, and they may feel detached and uninvolved with the infant's care (Latva, Korja, Salmelin, Lehtonen, & Tamminen, 2008). Even after the infant leaves the hospital, the transition from hospital to home care is a potentially stressful time for parents of preterm infants, as parents must assume total responsibility for an infant whose care has been previously managed primarily by others. Mothers of preterm infants often show symptoms of depression and anxiety (Poehlmann, Schwichtenberg, Bolt, & Dilworth-Bart, 2009; Voegtline & Stifter, 2010), and the potentially traumatic experience of preterm delivery may lead to the emergence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in some cases (DeMier et al., 2000; Kersting et al., 2004). All of these factors could affect feelings of stress about parenting, as well as the quality of early interactions between mothers and premature infants (Muller-Nix et al., 2004; Singer et al., 2003).

In mother–preterm infant dyads, higher levels of parenting stress could be seen as either an indicator of maternal trauma, or as a response to poorer interactive behaviors and less optimal responsivity in their preterm children. Several studies have analyzed the level of parenting stress comparing parents of preterm and full-term children. Results have been mixed, with some studies finding higher levels of parenting stress in mothers of preterm children compared with mothers of full-term children (Brummelte, Grunau, Synnes, Whitfield, & Petrie-Thomas, 2011; Singer et al., 1999), and others failing to find such differences (Gray, Edwards, O'Callaghan, & Cuskelly, 2012; Halpern, Brand, & Malone, 2001; Treyvaud et al., 2011).

The inconsistency in these results suggests that even if prematurity itself could be considered a risk factor for the emergence of parenting stress, some mothers of preterm infants are more able to deal with such experiences and others are less able. By limiting analyses to comparisons of preterm and full-term groups, our understanding of variability within families of preterm infants and knowledge of the premature infant–mother relationship in relation to parenting stress over time may be incomplete.

Within a transactional perspective, the study of the experience of parenting a preterm infant could not be considered as a product of infant prematurity alone as a single risk factor. The development of the preterm infant–mother relationship is the product of the interplay of infant, maternal, and contextual factors. Within this approach, other variables like maternal and infant characteristics could play an important role in influencing how stressful mothers perceived parenting their preterm infants. Within-group designs, such as those focusing on samples of families with preterm infants, can highlight the diverse challenges and strengths that families with a preterm infant experience and can foster our understanding of resilience in these high-risk families. Furthermore, longitudinal studies could draw attention to the role of maternal and infant factors in influencing the levels of the stress experienced by parents over time, in different moments of the infant's life.

Preterm Infant Characteristics and Parenting Stress

Severity of prematurity and neonatal complications (e.g., duration of ventilation, respiratory distress, cerebral hemorrhages) can influence the long-term development of the child and the development of mother–infant relationship. The anxiety caused by the threatened loss of the infant may significantly change the way a parent perceives and interacts with the infant. Infants born preterm and with neonatal complications may be hospitalized for longer than other infants, and the length of hospitalization seems to have an effect on the stress experienced by parents (DeMier et al., 2000). The sicker the infant, the higher is the level of parenting stress reported by mothers after hospital discharge (Holditch-Davis et al., 2009), and mothers of low-birth-weight infants experience a slower rate of parenting stress decrease over time compared with mothers of healthy-term infants (Singer et al., 2010).

Moreover, parenting multiples, which are more likely to be delivered preterm and have low birth weight, could also be a more stressful experience due to the growing demands of having more than one child (Feldman, Eidelman, & Rotenberg, 2004; Lutz et al., 2012).

These results of previous studies show the complexity of the effects of stressful perinatal infant characteristics on the parent–infant relationship, as well as the importance of not considering all premature infants as a homogeneous group.

Maternal Characteristics and Parenting Stress

The mother–infant relationship is affected by individual characteristics as well as the ecological and psychosocial context. In a sample of African American mothers of preterm infants, Candelaria, O'Connell, and Teti (2006) found that cumulative psychosocial risk, including low maternal education, social support and parental attitudes, but not infant medical risk, predicted parenting stress in the early postpartum period. In another sample of premature infants, mothers who reported higher stress related to the NICU experience, and more depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms, were also the mothers with the lowest education level (Holditch-Davis et al., 2009). Furthermore, in a recent study, maternal depressive symptoms were found to be independent predictors of parenting stress in a sample of preterm-infant mothers (Gray et al., 2012).

There is growing evidence that social support and family resources play an important role in the ability of parents to deal with the overwhelming experience of the NICU, and of the first interaction with the child, reducing the level of stress experienced by mothers (Pinelli, 2000). Singer, Davillier, Bruening, Hawkins, and Yamashita (1996) reported that lower general social support predicted high distress levels, but only for mothers of very-low-birth-weight infants.

Research Questions

As the recent literature highlights, the study of parenting stress in mothers of premature infants needs to take into consideration variables that may play an important role in influencing its development. Most noticeable is the need for more longitudinal studies exploring potential changes in parenting stress over time. Within a transactional perspective, there are likely to be changes in the amount and type of stress parents experience, but the factors that contribute to stress at one point in time may or may not contribute to its change over time.

Given these issues, we examined predictors of parenting stress in mothers of preterm infants and its variations longitudinally over the first 3 years of infant life. The first goal of the study was to examine individual differences in parenting stress trajectories in mothers of preterm infants at 4, 24, and 36 months postterm. We presumed that there would be individual variations in trajectories over time. We also expected variations in trajectories between the different aspects of parenting stress (i.e., stress related to the child and to parenting, and the total stress experienced).

Within a transactional perspective, the second goal of the study was to examine infant and maternal characteristics and risk factors as predictors of maternal parenting stress at 4 months postterm (i.e., intercept) and the rate of change in parenting stress between 4 months and 36 months (i.e., the slope).

Studies focusing on the impact of parenting stress on the development of the parent–child relationship during early childhood have emphasized that an increased level of stress may be associated with maladaptive parenting (Muller-Nix et al., 2004; Singer et al., 2003). For this reason, the third goal of the study, at an exploratory level, was to examine how maternal parenting stress and the quality of maternal interaction covaried over time. We expected that they would be strongly linked.

Method

Participants

This report focuses on data from 125 premature infants and their mothers. This sample was drawn from a larger longitudinal study that included 181 mothers with infants born preterm or with low birth weight (Poehlmann et al., 2009). Participants of the larger study were recruited from three NICUs in southeastern Wisconsin between 2002 and 2005. A research nurse from each hospital invited families to participate in the study if (a) the infant was born <35 weeks gestation or weighed <2,500 g at birth; (b) the infant had no known congenital problems or significant neurological findings during the NICU stay (e.g., Down's syndrome), and no prenatal drug exposures; (c) the mother was at least 17 years of age; (d) the mother could read English; and (e) the mother self-identified as the child's primary caregiver. For multiple births, one infant was randomly selected to participate in the study. Characteristics of participating families paralleled the population of Wisconsin during the years of data collection, although with more racial diversity in the sample.

The 125 infants included in this study had mothers who completed the Parenting Stress Index (PSI) at one or more time points. Data from two mothers were excluded because their infants were diagnosed with cerebral palsy or autism spectrum disorder by 36 months of age.

Participants in this sample did not differ from the full sample regarding any maternal, infant, or family characteristics. Our sample consisted of 77.6% White, 12% African American, 3.2% Latino, 2.4% Asian, 0.8% Middle Eastern, and 4.8% multiracial mothers. Prior to the infant's NICU discharge, 72.8% of the mothers were employed, 8% were teenagers, and 18% of the families lived in poverty, according to federal guidelines (adjusted for family size). Further characteristics of the sample are described in Table 1.

Table 1. Sample Demographic Information.

| Range | Frequencies | % | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 17–42 | 29.82 | 6.34 | ||

| Maternal education (years) | 8–21 | 14.41 | 2.63 | ||

| Family income/year | 0–500,000 | 60,956 | 56,903 | ||

| Single mothers | 10 | 8 | |||

| Infant gender | |||||

| Male | 65 | 52 | |||

| Female | 60 | 48 | |||

| Multiple birth | 24 | 19.2 | |||

| Firstborn child | 72 | 57.6 | |||

| Infant gestational age (weeks) | 23.7–36.4 | 31.64 | 3.09 | ||

| Infant birth weight (g) | 564–3328 | 1743.52 | 594.51 | ||

| Extremely low (<1,000 g) | 21 | 16.8 | |||

| Very low (<1,500 g) | 24 | 19.2 | |||

| Low (<2,500 g) | 68 | 54.4 | |||

| Normal (≥2,500 g) | 12 | 9.6 | |||

| Days in the hospital | 4–136 | 32.44 | 28.34 |

Procedure

Mothers and infants of the larger study were assessed at seven time points from prior to the infant's NICU discharge to 6 years corrected age. Corrected age was calculated on the basis of the infant's due date (DiPietro & Allen, 1991). This study focused on data collected prior NICU discharge and at 4, 24, and 36 months of infants corrected age.

An institutional review board-approved brochure was distributed to families in each NICU, and a research nurse described the study to eligible families. Interested mothers returned the signed informed-consent forms to nurses. By appointment, a researcher met the mother at the NICU just prior to the infant's discharge to collect data. On this occasion, mothers were videotaped during feeding interactions, they completed the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) and the Maternal Support Scale, and demographic variables were collected. Shortly after NICU discharge, nurses completed a history-of-hospitalization form by reviewing the infant's medical records.

When infants were 4 months corrected age, a home visit was conducted. During this visit, we asked mothers to complete the PSI and videotaped mother–infant interactions. The home visit lasted approximately 1.5 hr and mothers were paid $25. When infants were 24 and 36 months postterm, families visited our laboratory playroom. Mothers and children were videotaped playing together, and mothers completed the PSI. Each of the laboratory visits lasted approximately 1.5 to 2 hr. Mothers were paid $80 at the 24-month visit and $85 at the 36-month visit. Children were given an age-appropriate book or toy at each visit.

Measures

Neonatal health risks

After infants' NICU discharge, medical records were reviewed and a neonatal health risk index was calculated. This index is the sum of the presence of eight neonatal medical risks, each dichotomized (1 = present, 0 = absent): diagnosis of apnea (72%), respiratory distress (59%), chronic lung disease (10%), gastroesophageal reflux (10%), supplementary oxygen at NICU discharge (9%), apnea monitor at NICU discharge (42%), 5-min Apgar score less than 6 (3%), and ventilation during NICU stay (53%). Cronbach's alpha was .75.

Because infant birth weight and gestational age were highly correlated (r = .87, p < .001), we selected gestational age as an infant index of prematurity. We also included as predictors whether the infant was a multiple (0 = no, 1 = yes) and the total number of days the infant was hospitalized.

Family socioeconomic risks

Mothers completed a demographic questionnaire while their infants were in the NICU. On the basis of previous research with high-risk infants (Burchinal, Roberts, Hooper, & Zeisel, 2000), a socioeconomic risk index was then calculated by summing the presence of the following risk factors: family income below federal poverty guidelines (adjusted for family size), both parents unemployed, single mother, adolescent mother, and four or more dependent children in the home. Scores ranged from 0 to 5, with higher scores reflecting more risk (Cronbach's alpha = .75). Maternal education was also included as an independent predictor.

Social support

Maternal report of global satisfaction with social support was assessed using the Maternal Support Scale (Infant-Parent Interaction Lab, 2009) prior to infant hospital discharge. This measure consists of 35 questions that begin with, “Do you receive any support from …?” and that refer to different aspects of support: emotional, information, instrumental (household, childcare, financial, rest), and other. Mothers answered “yes” or “no” with respect to the support received from the baby's father, the mother's parents, the baby's father's parents, the extended family, and eventually other adults that live with the family (Cronbach's alpha = .84).

Maternal depressive symptoms

The CES-D (Radloff, 1977) was used to assess maternal depressive symptoms prior to infants' NICU discharge. The CES-D is a 20-item self-report questionnaire that asks respondents to rate their symptoms in the previous week on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (rarely/none of the time) to 3 (most/all of the time). Scores of 16 and higher are considered in the clinical range. (Cronbach's alpha = .79).

Quality of infant-mother interactions

Infant–mother feeding interactions prior to NICU discharge, and infant–mother play interactions at 4, 24, and 36 months postterm, were videotaped and coded using the Parent–Child Early Relational Assessment (PCERA; Clark, 1985).The PCERA is a system designed to assess the frequency, duration, and intensity of affect and behavioral characteristics of parents and infants that occur during 5 min of face-to-face interactions. On the basis of the 5-min observation, each variable is coded on a scale ranging from 1 (negative relational quality) to 5 (positive relational quality). In the present study, we focused on the 29 parent variables that could be coded at each time. These included tone of voice, affect and mood, attitude toward the child, affective and behavioral involvement, and style. A total parental interaction quality scale and established parent subscales that have been used in previous research (Durik, Hyde, & Clark, 2000) were calculated. The three parent subscales were Positive Affect, Involvement, and Verbalizations (PCERA Subscale 1), Negative Affect and Behavior (PCERA Subscale 2), and Intrusiveness, Insensitivity, and Inconsistency (PCERA Subscale 3). For each scale, higher scores indicate better quality of interaction.

In the present study, we used mothers' total interaction quality score during feeding prior to infant NICU discharge (PCERA Hospital Discharge score: PCERA HD) as a maternal predictor of parenting stress. The maternal interactive quality during free-play subscales scores (PCERA Subscales 1, 2, and 3) at 4, 24, and 36 months postterm were used to analyze the covariation over time with parenting stress (see Table 2 for PCERA subscales descriptive statistics at each time point).

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics for the Parenting Stress Index and the PCERA Subscale Scores at Each Time Point.

| 4 months | 24 months | 36 months | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Range | M (SD) | Range | M (SD) | Range | M (SD) | |

| PSI Child Domain | 58–151 | 92.62 (15.33) | 62–160 | 100.28 (18.38) | 53–146 | 98.96 (18.73) |

| PSI Parent Domain | 66–177 | 112.57 (20.69) | 68–194 | 117.39 (21.71) | 63–179 | 115.67 (22.48) |

| PSI Total Stress | 136–320 | 205.19 (32.12) | 135–354 | 217.68 (35.24) | 117–321 | 214.63 (37.33) |

| PCERA Subscale 1 | 1.82–5.00 | 3.98 (.62) | 1.43–4.91 | 3.71 (.68) | 2.05–4.89 | 3.57 (.61) |

| PCERA Subscale 2 | 2.80–5.83 | 4.41 (.55) | .73–5.00 | 3.82 (.81) | 2.00–5.97 | 4.37 (.76) |

| PCERA Subscale 3 | 2.38–5.00 | 3.98 (.57) | 2.25–5.00 | 3.92 (.53) | 2.88–4.90 | 4.08 (.41) |

Note. PCERA = Parent–Child Early Relational Assessment; PSI = Parenting Stress Index; PCERA Subscale 1 = Positive Affect, Involvement, and Verbalizations; PCERA Subscale 2 = Negative Affect and Behavior; PCERA Subscale 3 = Intrusiveness, Insensitivity, and Inconsistency.

Ten percent of the larger sample was independently coded by four trained research assistants at each time point, and interrater reliability ranged from 83% to 97% across codes and time points, with a mean of 88% agreement (the PCERA standard). The PCERA has an acceptable range of internal consistency (Clark, 1999; in the current study, on average, across times: PCERA 1 = .95, PCERA 2 = .89, PCERA 3 = .93) and discriminate validity between high-risk and well-functioning mothers (Clark, Paulson, & Conlin, 1993). The PCERA has been used previously with preterm infants (Brown, 2007), and has been linked to their subsequent developmental and behavioral outcomes (Poehlmann, Schwichtenberg, Bolt, et al., 2011; Poehlmann, Schwichtenberg, Shlafer, et al., 2011).

Parenting stress

At 4, 24, and 36 months, mothers completed the PSI (Abidin, 1995). The PSI is a commonly used self-report questionnaire that measures stress related to the parenting role. It is widely used by clinicians and researchers in screening, diagnostic assessment, and measurement of intervention.

This instrument includes 101 items that are rated from 1 to 5 on a Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) and 20 items rated on a yes–no scale. Items are divided into a total scale, two domain scales, and 13 subscales. The Child Domain scale is linked to child qualities that make difficult for parents to fulfill their parental role (i.e., “My child gets upset easily over the smallest thing”) and it includes six subscales. The Parent Domain scale addresses sources of stress related to dimensions of parental functioning, including parent personality and situational variables (i.e., “I feel trapped in my responsibilities as a parent”) and it involves seven subscales. The Total Stress scale indicates the total stress perceived by the parents throughout the parenting experience and it reflects the sum of the Child Domain and Parent Domain scales scores. Higher scores represent a higher amount of parenting stress. Finally, the PSI provides a Life Stress scale, an index of stress outside the parent–child relationship.

For the purpose of this study, we included the three main scales of Child Domain, Parent Domain, and Total Stress in the analysis. For the present study, Cronbach's alphas were as follows (at 4/24/36-month time points): Child Domain scale,.86/.89/.90; Parent Domain scale, .90/.90/.91; and Total Stress scale, .90/.91/.93 (see Table 2 for PSI scale descriptive statistics at each time point).

Missing Data

Some missing values existed for maternal interaction quality, social support, and parenting stress variables (social support, 0.8%; PCERA HD, 7.2%; 4-month PCERA, 4%; 24-month PCERA, 5.6%; 36-month PCERA, 14.4%; 4-month PSI, 9.6%; 24-month PSI, 6.4%; 36-month PSI, 8%). We used a multiple imputation procedure to address the presence of missing data. Five data sets were generated in which missing values were randomly generated conditional on all other variables in the analysis using SPSS version 20. Subsequent modeling procedures were applied to all five datasets, with aggregated results reported for the final models.

Plan of Analysis

We used two-level hierarchical linear models (HLMs) to study individual change in mother's parenting stress levels over time (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002; Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, Congdon, & du Toit, 2011). This approach is increasingly being used in developmental and family research. By using multilevel analyses, it is possible to estimate individual growth equations and the effect of independent variables on them. Due to our three-time-point design, we restricted our analysis to linear models, as additional random polynomial terms would exhaust our degrees of freedom. The Level 1 model specified individual change in each PSI scale (Child Domain, Parent Domain, and Total Stress) as a linear function of time. The Level 2 model explained variability in the intercept and slope as a function of maternal and infant variables, and allowed both the intercepts and slopes to be random across persons. Separate models were run using each PSI scale as an outcome. Time was centered at 4 months so that the intercept corresponded to the expected score at the time when the first measure was taken (4 months postterm), and the slope indicated the estimated change per month (from 4 months to 36 months postterm).

Additionally, a model was specified to assess the covariation between the parenting stress and maternal interaction quality trajectories over time. In this model, all outcomes are modeled simultaneously in relation to their own unique intercept and slope trajectories. The purpose of this analysis was to evaluate the strength of association between the trajectory intercepts and slopes across the different outcomes. To further examine the relationship between stress and parent interaction variables, a series of cross-lagged path models were fitted in which both stress and parent interaction were modeled as a function of both the prior stress score and prior parent interaction score.

Restricted maximum likelihood estimation was used in all models, and because sample sizes were sufficiently high, robust standard errors based on generalized estimating equations (Zeger & Liang, 1986), as provided in the HLM software, were used in performing significance tests.

Results

Unconditional Model

We initially examined three unconditional models to quantify variance in trajectory parameters across individuals for the three PSI scales considered separately. These models included the Level 1 predictor of time (i.e., months), but no predictors at Level 2. Mothers showed significant variability with respect to the intercept (i.e., 4-month PSI scores) and slopes for all PSI scales: Child Domain, χ2(124) = 235.14, p < .001, Parent Domain, χ2(124) = 345.39, p < .001, and Total Stress, χ2(124) = 342.83, p < .001, for the intercepts; Child Domain, χ2(124) = 194.63, p < .001, Parent Domain, χ2(124) = 194.71, p < .001, and Total Stress, χ2(124) = 234.87, p < .001, for the slopes. These findings suggest variability in both intercepts and slopes that has the potential to be explained by Level 2 predictors.

Table 3 displays the results of the two-level HLM models that entered predictors of both the intercepts and slopes. All predictor variables were entered as uncentered, with the exception of gestational age and PCERA HD (parent interaction quality during feeding at hospital discharge), both of which were grand-centered. As a result, the intercepts of the B00 and B10 equations can, in each case, be interpreted as the expected value of the trajectory parameter (intercept or slope) when all predictors are at 0, with the exception of gestational age and PCERA HD, which would be at their mean levels.

Table 3. Linear Estimates for Parenting Stress Index Scales.

| PSI Child Domain Scale | PSI Parent Domain Scale | PSI Total Stress Scale | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Variable | Coefficient | t | df | p | Coefficient | t | df | p | Coefficient | t | df | p |

| B00 | ||||||||||||

| Intercept | 112.66 | 10.95 | 115 | <.001*** | 137.44 | 12.21 | 115 | <.001*** | 250.11 | 12.63 | 115 | <.001*** |

| Multiple birth | 2.61 | 0.75 | 115 | .456 | 15.34 | 3.28 | 115 | .001** | 17.95 | 2.60 | 115 | .011* |

| Days in the hospital | −0.13 | −1.14 | 115 | .255 | −0.43 | −2.66 | 115 | .009** | −0.56 | −2.41 | 115 | .018* |

| Gestational age | −0.73 | −0.77 | 115 | .441 | −2.13 | −1.50 | 115 | .136 | −2.87 | −1.46 | 115 | .146 |

| Neonatal risks | 1.20 | 1.23 | 115 | .222 | 3.20 | 2.60 | 115 | .011* | 4.41 | 2.25 | 115 | .026* |

| Maternal education | −1.34 | −2.48 | 115 | .015* | −1.81 | −2.86 | 115 | .005** | −3.14 | −2.96 | 115 | .004** |

| Socioeconomic risk | 1.24 | 0.79 | 115 | .432 | 0.36 | 0.16 | 115 | .874 | 1.59 | 0.50 | 115 | .619 |

| Social support | −0.13 | −0.51 | 115 | .614 | −0.11 | −0.37 | 115 | .709 | −0.24 | −0.51 | 115 | .608 |

| CES-D depression | 0.13 | 0.98 | 115 | .330 | 0.43 | 2.35 | 115 | .020* | 0.57 | 1.99 | 115 | .049* |

| PCERA HD | 0.03 | 0.41 | 115 | .679 | −0.01 | −0.12 | 115 | .901 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 115 | .901 |

| B10 | ||||||||||||

| Intercept | −0.01 | −0.02 | 115 | .985 | −0.87 | −1.90 | 115 | .060 | −0.88 | −1.02 | 115 | .308 |

| Multiple birth | −0.18 | −1.21 | 115 | .231 | −0.38 | −2.04 | 115 | .043* | −0.55 | −1.88 | 115 | .062 |

| Days in the hospital | −0.00 | −0.37 | 115 | .711 | −0.01 | −0.14 | 115 | .887 | −0.01 | −0.28 | 115 | .782 |

| Gestational age | 0.01 | 0.33 | 115 | .744 | −0.04 | −0.72 | 115 | .476 | −0.02 | −0.25 | 115 | .806 |

| Neonatal risks | −0.03 | −0.58 | 115 | .560 | −0.04 | −0.91 | 115 | .366 | −0.07 | −0.82 | 115 | .415 |

| Maternal education | 0.02 | 0.72 | 115 | .475 | 0.05 | 2.06 | 115 | .042* | 0.07 | 1.54 | 115 | .126 |

| Socioeconomic risk | 0.00 | 0.49 | 115 | .626 | 0.08 | 0.84 | 115 | .403 | 0.12 | 0.79 | 115 | .430 |

| Social support | 0.01 | 0.54 | 115 | .590 | 0.03 | 1.88 | 115 | .063 | 0.03 | 1.41 | 115 | .162 |

| CES-D depression | 0.00 | 0.11 | 115 | .908 | 0.00 | 0.56 | 115 | .577 | 0.00 | 0.37 | 115 | .709 |

| PCERA HD | 0.00 | 0.01 | 115 | .994 | 0.01 | 1.20 | 115 | .234 | 0.01 | 0.71 | 115 | .480 |

Note. N = 125. PSI = Parenting Stress Index; B00 = intercepts in the HLM model; B10 = slopes in the HLM model; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale; PCERA = Parent–Child Early Relational Assessment; PCERA HD = parent interaction quality during feeding at hospital discharge.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

PSI Child Domain

Examination of the coefficients and associated t tests for the PSI Child Domain scores indicated statistically lower scores at 4 months (intercept) for higher maternal education (see Table 3). Specifically, for each additional year of maternal education, parenting stress scores related to child characteristics were 1.3 units lower. None of the other variables included in the model significantly predicted either the intercept or the slope.

PSI Parent Domain

For the Parent Domain Scale of the PSI, many more significant effects were detected.

Mothers of multiples, mothers of infants with more neonatal health risks, and mothers with more depressive symptoms reported higher parenting stress related to dimensions of parental functioning at 4 months, whereas mothers with higher educational levels and mothers with infants who spent more time in the hospital reported significantly lower parenting stress. In predicting the slope, the results indicate that multiple birth and maternal education significantly predicted the Parent Domain score trajectories over time. Multiple-birth mothers demonstrated a more negative decrease (or less positive increase, depending on levels of other predictors) in the Parent Domain scores, whereas higher levels of education related to a less negative decrease (or more positive increase) in the slope.

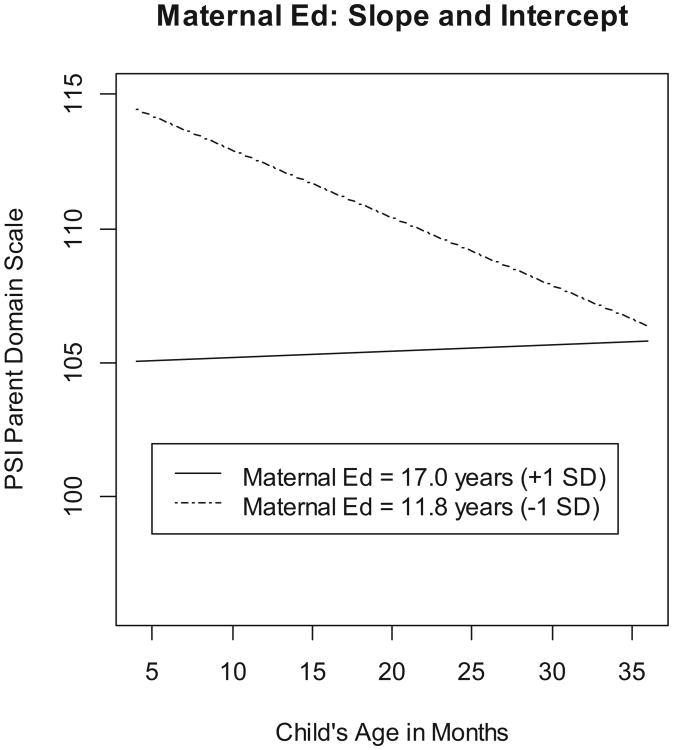

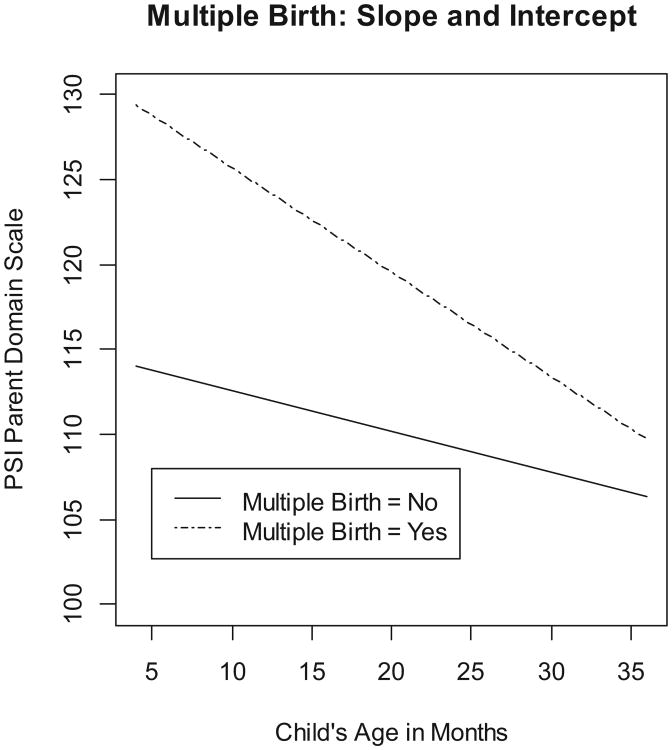

Because of the large number of significant predictors in the Parent Domain score analysis, and the consistency in the direction of effects with significant outcomes with that observed for other scales, we illustrate the significant effects for the predictors maternal education and multiple birth (having significant effects for both the slopes and the intercepts) in Figures 1 and 2. Each figure illustrates the effect of a significant predictor in reference to two hypothetical individuals that vary in the studied predictor but are at the same fixed levels on all other predictors (12 years for maternal education, and 0 for multiple births).

Figure 1.

Mother's parenting stress scores between 4 months and 36 months postterm for the PSI Parent Domain scale slope and intercept significant predictor maternal education. Maternal ed = maternal education in years.

Figure 2.

Mother's parenting stress scores between 4 months and 36 months postterm for the PSI Parent Domain scale slope and intercept significant predictor multiple birth.

PSI Total Stress

The patterns of significant results observed for the Total Stress scale were very similar to the Parent Domain scale. The intercept of the total stress expressed by mothers was predicted by the same variables that predicted Parent Domain scores. Mothers of multiples, mothers of infants with more neonatal risks, and mothers of infants who spent fewer days in the hospital reported more total stress. With respect to maternal characteristics, both higher maternal education and less depressive symptoms predicted less total stress at 4 months. None of the predictors in the model significantly predicted the Total Stress scale's slope.

Covariation of Parenting Stress and Maternal Interaction Quality

Results of the multivariate model jointly analyzing PSI scales and PCERA maternal interaction quality and their trajectories over time are reported in Table 4. The table displays the average intercept and slope for all six outcomes. The mean slopes for the PCERA Positive Affect, Involvement, and Verbalizations subscales were significantly negative, implying an average decrease over time in this outcome, but were significantly positive for the Child Domain PSI scale and Total Stress PSI scale, implying an average increase over time.

Table 4. Fixed and Random Effects Estimates for Trajectory Covariation Model.

| Fixed effect parameter estimates | Correlation | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| Parameter | Coefficient | T | Df | p | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| PCERA 1 intercept | 3.97 | 61.45 | 124 | <.001 | — | |||||||||||

| PCERA 2 intercept | 4.28 | 65.61 | 124 | <.001 | .10 | — | ||||||||||

| PCERA 3 intercept | 3.95 | 71.44 | 124 | <.001 | .20* | .12 | — | |||||||||

| CDOM intercept | 93.26 | 67.92 | 124 | <.001 | −.17 | −.04 | −.15 | — | ||||||||

| PDOM intercept | 113.52 | 62.67 | 124 | <.001 | −.04 | .07 | −.00 | .72* | — | |||||||

| TSTRESS intercept | 206.79 | 72.43 | 124 | <.001 | −.10 | .03 | −.07 | .90* | .95* | — | ||||||

| PCERA 1 slope | −0.01 | −4.76 | 124 | <.001 | −.78* | −.08 | −.15 | .21 | .11 | .16 | — | |||||

| PCERA 2 slope | 0.00 | −1.19 | 124 | .237 | −.02 | −.74* | −.02 | −.14 | −.12 | −.14 | .05 | — | ||||

| PCERA3 slope | 0.00 | 1.065 | 124 | .289 | −.12 | −.08 | −.78* | .01 | −.04 | −.02 | .15 | .10 | — | |||

| CDOM slope | 0.22 | 3.92 | 124 | <.001 | .17 | .13 | .13 | −.44* | −.29* | −.38* | −.30* | −.09 | −.14 | — | ||

| PDOM slope | 0.10 | 1.64 | 124 | .103 | .21* | .12 | .18 | −.46* | −.43* | −.47* | −.27* | −.01 | −.11 | .82* | — | |

| TSTRESS slope | 0.33 | 2.99 | 124 | .003 | .20* | .13 | .16 | −.47* | −.38* | −.45* | −.29* | −.05 | −.13 | .95* | .95* | — |

Note. PCERA 1 = Positive Affect, Involvement, and Verbalizations; PCERA 2 = Negative Affect and Behavior; PCERA3 = Intrusiveness, Insensitivity, and Inconsistency; CDOM = PSI Child Domain Scale; PDOM = PSI Parent Domain Scale; TSTRESS = PSI Total Stress Scale.

p < .01, based on Fisher r-to-z approximation.

Our main interest in the covariation analysis was to determine if parenting stress trajectories covaried over time with quality of mother–infant interaction. The correlations between slopes across scales and subscales showed that maternal scores in the PCERA Positive Affect, Involvement, and Verbalizations subscales were significantly negatively correlated with all of the PSI scales. An increase in parenting stress over the first 3 years postterm corresponded to a decrease in maternal positive affective behaviors during interaction with the infant.

To further examine the relationship between stress and parent-interaction variables, we fit a series of cross-lagged path models in which both stress and parent interaction at a particular time point were modeled as a function of both the prior stress score and prior parent interaction score. We failed to find statistical significance for any of the cross-lagged effects, perhaps due, in part, to measurement error in the individual measures as well as reduced statistical power in trying to quantify these separate effects. For this reason, results of the cross-lagged model are not reported but are available upon request.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the development of parenting stress during the child's first 3 years of life in a sample of mothers with preterm infants. Our analysis of unconditional models showed significant individual variability across mothers with respect to parenting stress at 4 months and parenting stress trajectories between 4 and 36 months. Parenting stress increased very slightly, on average, between 4 and 36 months, a result that is in line with what has been found in other studies with mothers of preterm infants (Singer et al., 1999). However, the most important result is that there was significant individual variability in slopes, indicating that change trajectories differed across mothers. This result confirms that mothers of preterm infants are not a homogenous group, and it suggests the importance of analyzing individual differences in parenting stress as well as factors that could influence these differences. Parenting a preterm infant can be a stressful experience, although it is clear that the level of stress experienced by mothers differs depending on a number of maternal and infant characteristics.

Maternal depressive symptoms prior to the infant's hospital discharge had a significant effect on maternal reports of stress in the Parent Domain and Total Stress scales at 4 months postterm, with more symptoms corresponding with more perceived parenting stress. Previous studies have also found links between maternal depressive symptoms and parenting stress (Holditch-Davis et al., 2009). When experienced as traumatic, preterm delivery could have an impact on maternal well-being, increasing the possibility of developing depressive symptoms right after childbirth (Miles, Holditch-Davis, Schwartz, & Scher, 2007). Elevations in depressive symptoms prior to the infant's NICU discharge may predispose a mother to experiencing parenting her preterm infant as stressful. These findings support the practice of screening for maternal depressive symptoms in the NICU setting, so that mothers with elevated symptoms can be referred for treatment to prevent or ameliorate the negative consequences of depression for preterm infants. Studies have consistently documented the negative effects of elevated maternal depressive symptoms on dyadic and child outcomes for preterm infants, including child self-regulation problems (Poehlmann, Schwichtenberg, Shah, et al., 2010) and less optimal mother–infant interaction quality (Korja et al., 2008). The present study extends this research by documenting significant covariation in parenting stress and maternal interaction quality over time. Specifically, increasing parenting stress between 4 and 36 months was associated with decreases in positive maternal behaviors during play interactions with the infant during the same time period. This finding is consistent with transactional developmental models that suggest that parental well-being is linked with parenting interactions over time (Muller-Nix et al., 2004; Webster-Stratton, 1990) and that underline the need to monitor the development of parenting stress in mothers of preterm infants to prevent further relational difficulties.

Transactional models also suggest that infant characteristics affect parental well-being. Parenting a preterm infant with medical complications may be perceived as more demanding and stressful than parenting a healthy preterm infant, which has implications for parental well-being. In the present study, we found that the number of neonatal risk factors had an effect on parenting stress scores at 4 months postterm. Mothers with higher-risk infants reported more parenting stress than mothers with lower-risk infants. This could be explained by considering these children as potentially more difficult to care for due to the medical complications they had after birth, as well as a result of the traumatic impact that seeing their infants experiencing neonatal medical complications could have on mothers (DeMier et al., 2000). These mothers may continue perceiving their infants as more at risk and could have more difficulties in coping with the parental role (Padovani, Linhares, Pinto, Duarte, & Martinez, 2008). The lack of information and the state of uncertainty about the possible consequences of these medical complications on preterm infants may leave mothers in a continuous stressful situation, especially right after hospital discharge. In contrast, mothers whose infants were hospitalized for more days showed less stress at 4 months postterm. Even though infant hospitalization has been found to have an impact on maternal well-being (Miles et al., 2007), a link between the length of infant hospitalization and the emergence of maternal psychological symptoms has not always been found (Poehlmann et al., 2009; Candelaria et al., 2006). We suggest the possibility that spending more time in the hospital gives mothers more time to recover from the preterm delivery to get ready to handle their infants at home later. The important role of nursing support during infant hospitalization could help these mothers to understand infant cues and infant difficulties, allowing mothers to cope more effectively with parenting after hospital discharge.

The infant variable that seemed to have the strongest effect on the development of parenting stress was multiple birth. Mothers of multiples reported significantly higher levels of parenting stress at 4 months than mothers of singletons. However, parenting stress levels in mothers of multiples decreased more over time than stress levels in mothers of singletons. Relating to two or more babies at the same time can be highly demanding, and may cause fatigue and corresponding depression and anxiety (Leonard, 1998), especially during the first months after delivery. Over time, this level of stress appears to decrease. Mothers of multiples probably become accustomed to the caregiving necessities of multiples, thanks also to the support they receive from families and social services (Lutz et al., 2012). Investigating social support that mothers of preterm multiples receive over time could help explain this association. In the present study, social support at the time of hospital discharge was not a significant predictor of parenting stress at 4 months or in change trajectories for mothers of preterm infants, although we did not examine social support as a moderator of the relation between multiple birth and maternal outcomes or support once the children came home from the hospital.

Our models also indicated that maternal education was a potent predictor of parenting stress. Mothers with higher educational levels showed less parenting stress in all the PSI scales analyzed. It seems that these mothers may be more equipped to handle the potentially stressful condition of caregiving for a preterm infant, especially during the first period after delivery compared with mothers with lower education. This result is consistent with what found in other studies highlighting maternal education as a risk factor in the development of parenting stress (Candelaria et al., 2006; Holditch-Davis et al., 2009) as well as other negative maternal outcomes like depressive and anxious symptoms (Davis, Edwards, Mohay, & Wollin, 2003). It is interesting that maternal education was the only variable that significantly predicted the intercept of the Child Domain stress score. Mothers with lower education may attribute to their 4-month-old preterm infants qualities that make it difficult for mothers to fulfill their parental role, or they may have unrealistic expectations of preterm infant behaviors at 4 months.

Maternal education also influenced the direction of parenting stress trajectories over time for the Parent Domain score. As shown in Figure 1, the level of parenting stress of mothers with lower educational levels decreased more rapidly over time compared with other mothers. Mothers with lower education may have experienced more difficulties in initially adapting to the stressful condition of raising a preterm infant, but then they seemed to find more productive ways to deal with it over time. By 3 years of age, the stress of lower-education mothers was at a level similar to the other mothers.

Our results underline the necessity of organizing specific interventions for mothers of medically fragile preterm infants in order to prevent increasing parenting stress and improve mothers' experiences of parenting as fulfilling. Parenting stress represents an important variable to consider as an indicator of risk for maladaptive parenting. At the same time, more attention should be given to mothers with lower education, giving them more information and instrumental supports that could help them understanding and deal with the experience of motherhood in the context of prematurity. When determining how to target such interventions, careful attention should be paid to risk factors that may be associated with elevated or increasing patterns of parenting stress, rather than assuming a one-size-fits-all model. There is significant individual variability in the experience of parenting a preterm infant, with many parents coping well and others struggling with their roles.

Our findings suggest that even though parenting a preterm infant might be a difficult experience, there is wide variability among individuals. Relevant risk factors for the development of parenting stress, besides prematurity, could be pointed out starting from hospital discharge. Furthermore, a transactional theory approach should be used in organizing preventive interventions for mothers of premature infants, so that parental, infant, and sociodemographic risk factors can be taken in account when developing and implementing such intervention programs.

The limitations of this study should be considered when interpreting and applying our findings. The longitudinal design is a strength, although the measurements of parenting stress did not have a consistent time lag between them. More time points, and measurements closer to each other, could give us more information about parenting stress trajectories over time. The predictors we took into consideration were measured just prior to the infant's hospital discharge, and during such a significant time lag, many other factors could play an important role in influencing parenting stress. For example, it might be interesting to study how the roles of social support, depressive symptoms, and other maternal and infant characteristics change over time in their influence on parenting-stress trajectories. We did not include a comparison group of mothers with full-term infants. This would help to document whether the same risk factors we found in our preterm sample would be applicable in a lower-risk group.

Despite these limitations, our study provides a contribution to the study of the well-being of mothers of preterm infants. Our findings could have important implications for the development of preventive interventions for this group of mothers.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HD44163) and the University of Wisconsin. Special thanks to the children and families who generously gave of their time to participate in this study.

Contributor Information

Maria Spinelli, Department of Psychology, University of Milano-Bicocca, Milan, Italy.

Julie Poehlmann, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Daniel Bolt, Department of Educational Psychology, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

References

- Aarnoudse-Moens CSH, Weisglas-Kuperus N, van Goudoever JB, Oosterlaan J. Meta-analysis of neurobehavioral outcomes in very preterm and/or very low birth weight children. Pediatrics. 2009;124:717–728. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abidin RR. Introduction to the special issue: The stresses of parenting. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1990;19:298–301. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp1904_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abidin RR. Parenting Stress Index. 3rd. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Benzies KM, Harrison MJ, Magill Evans J. Parenting stress, marital quality, and child behavior problems at age 7 years. Public Health Nursing. 2004;21:111–121. doi: 10.1111/j.0737-1209.2004.021204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown L. Heart rate variability in premature infants during feeding. Biological Research for Nursing. 2007;8:283–293. doi: 10.1177/1099800406298542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummelte S, Grunau RE, Synnes AR, Whitfield MF, Petrie-Thomas J. Declining cognitive development from 8 to 18 months in preterm children predicts persisting higher parenting stress. Early Human Development. 2011;87:273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2011.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal MR, Roberts JE, Hooper S, Zeisel SA. Cumulative risk and early cognitive development: A comparison of statistical risk models. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:793–807. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.36.6.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candelaria MA, O'Connell MA, Teti DM. Cumulative psychosocial and medical risk as predictors of early infant development and parenting stress in an African-American preterm sample. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2006;27:588–597. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2006.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cappa K, Begle A, Conger J, Dumas J, Conger A. Bidirectional relationships between parenting stress and child coping competence: Findings from the Pace Study. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2011;20:334–342. doi: 10.1007/s10826-010-9397-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R. The Parent–Child Early Relational Assessment instrument and manual. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Medical School; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Clark R. The Parent–Child Early Relational Assessment: A factorial validity study. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1999;59:821–846. doi: 10.1177/00131649921970161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Paulson A, Conlin S. Assessment of developmental status and parent-infant relationships: The therapeutic process of evaluation. In: Zeanah CH, editor. Handbook of infant mental health. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 191–209. [Google Scholar]

- Davis L, Edwards H, Mohay H, Wollin J. The impact of very premature birth on the psychological health of mothers. Early Human Development. 2003;73:61–70. doi: 10.1016/S0378-3782(03)00073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMier RL, Hynan MT, Hatfield RF, Varner MW, Harris HB, Manniello RL. A measurement model of perinatal stressors: Identifying risk for postnatal emotional distress in mothers of high-risk infants. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2000;56:89–100. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(200001)56:1<89::aid-jclp8>3.0.co;2-6. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(200001)56:1 <89::AID-JCLP8>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPietro JA, Allen MC. Estimation of gestational age: Implications for developmental research. Child Development. 1991;62:1184–1199. doi: 10.2307/1131162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durik AM, Hyde JS, Clark R. Sequelae of cesarean and vaginal deliveries: Psychosocial outcomes for mothers and infants. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:251–260. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.36.2.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R, Eidelman AI, Rotenberg N. Parenting stress, infant emotion regulation, maternal sensitivity, and the cognitive development of triplets: A model for parent and child influences in a unique ecology. Child Development. 2004;75:1774–1791. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray PH, Edwards DM, O'Callaghan MJ, Cuskelly M. Parenting stress in mothers of preterm infants during early infancy. Early Human Development. 2012;88:45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern LF, Brand KL, Malone AF. Parenting stress in mothers of very-low-birth-weight (VLBW) and full-term infants: A function of infant behavioral characteristics and child-rearing attitudes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2001;26:93–104. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/26.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holditch-Davis D, Mies MS, Weaver MA, Black B, Beeber L, Thoyre S, Engelke S. Patterns of distress in African-American mothers of preterm infants. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2009;30:193–205. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181a7ee53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infant-Parent Interaction Lab. Unpublished manuscript. Madison, WI: Waisman Center, University of Wisconsin; 2009. Maternal Support Scale. [Google Scholar]

- Kersting A, Dorsch M, Wesselmann U, Ludorff K, Witthaut J, Ohrmann P, et al. Arolt V. Maternal posttraumatic stress response after the birth of a very low-birth-weight infant. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2004;57:473–476. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korja R, Savonlahti E, Ahlqvist-Björkroth S, Stolt S, Haataja L, Lapinleimu H, et al. the PIPARI Study Group. Maternal depression is associated with mother–infant interaction in preterm infants. Acta Paediatrica (Oslo, Norway: 1992) 2008;97:724–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latva R, Korja R, Salmelin RK, Lehtonen L, Tamminen T. How is maternal recollection of the birth experience related to the behavioral and emotional outcome of preterm infants? Early Human Development. 2008;84:587–594. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard LG. Depression and anxiety disorders during multiple pregnancy and parenthood. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 1998;27:329–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1998.tb02656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz KF, Burnson C, Hane A, Samuelson A, Maleck S, Poehlmann J. Parenting stress, social support, and mother–child interactions in families of multiple and singleton preterm toddlers. Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies. 2012;61:642–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2012.00726.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MS, Holditch-Davis D, Schwartz TA, Scher M. Depressive symptoms in mothers of prematurely born infants. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2007;28:36–44. doi: 10.1097/01.DBP.0000257517.52459.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Nix C, Forcada-Guex M, Pierrehumbert B, Jaunin L, Borghini A, Ansermet F. Prematurity, maternal stress and mother–child interactions. Early Human Development. 2004;79:145–158. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Östberg M, Hagekull B. A structural modeling approach to the understanding of parenting stress. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29:615–625. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP2904_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padovani FH, Linhares MB, Pinto ID, Duarte G, Martinez FE. Maternal concepts and expectations regarding a preterm infant. The Spanish Journal of Psychology. 2008;11:581–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahl KM, Barrett PM, Gullo MJ. Examining potential risk factors for anxiety in early childhood. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2012;26:311–320. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinelli J. Effects of family coping and resources on family adjustment and parental stress in the acute phase of the NICU experience. Neonatal Network: The Journal of Neonatal Nursing. 2000;19:27–37. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.19.6.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poehlmann J, Schwichtenberg AM, Bolt D, Dilworth-Bart J. Predictors of depressive symptom trajectories in mothers of preterm or low birth weight infants. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:690–704. doi: 10.1037/a0016117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poehlmann J, Schwichtenberg AJ, Bolt DM, Hane A, Burnson C, Winters J. Infant physiological regulation and maternal risks as predictors of dyadic interaction trajectories in families with a preterm infant. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:91–105. doi: 10.1037/a0020719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poehlmann J, Schwichtenberg AJM, Shah PE, Shlafer RJ, Hahn E, Maleck S. The development of effortful control in children born preterm. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39:522–536. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2010.486319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poehlmann J, Schwichtenberg AJM, Shlafer RJ, Hahn E, Bianchi JP, Warner R. Emerging self-regulation in toddlers born preterm or low birth weight: Differential susceptibility to parenting? Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23:177–193. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000726. doi:10.1017/ S0954579410000726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Vol. 1. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Cheong YF, Congdon R, du Toit M. HLM 7: Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Lincoln Wood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff A, editor. The transactional model of development: How children and contexts shape each other. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singer LT, Davillier M, Bruening P, Hawkins S, Yamashita TS. Social support, psychological distress, and parenting strains in mothers of very low birthweight infants. Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies. 1996;45:343–350. doi: 10.2307/585507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer LT, Fulton S, Davillier M, Koshy D, Salvator A, Baley JE. Effects of infant risk status and maternal psychological distress on maternal-infant interactions during the first year of life. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2003;24:233–241. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200308000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer LT, Fulton S, Kirchner HL, Eisengart S, Lewis B, Short E, et al. Baley JE. Longitudinal predictors of maternal stress and coping after very low-birth-weight birth. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2010;164:518–524. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer LT, Salvator A, Guo S, Collin M, Lilien L, Baley J. Maternal psychological distress and parenting stress after the birth of a very low-birth-weight infant. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;281:799–805. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.9.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas KA, Renaud MT, DePaul D. Use of the parenting stress index in mothers of preterm infants. Advances in Neonatal care. 2004;4:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.adnc.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treyvaud K, Doyle LW, Lee KJ, Roberts G, Cheong JLY, Inder TE, Anderson PJ. Family functioning, burden and parenting stress 2 years after very preterm birth. Early Human Development. 2011;87:427–431. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voegtline KM, Stifter CA. Late-preterm birth, maternal symptomatology, and infant negativity. Infant Behavior & Development. 2010;33:545–554. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C. Stress: A potential disruptor of parent perceptions and family interactions. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1990;19:302–312. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp1904_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williford AP, Calkins SD, Keane SP. Predicting change in parenting stress across early childhood: Child and maternal factors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35:251–263. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–130. doi: 10.2307/2531248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]