Abstract

Conventional cognitive-behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder, which is closely based on the treatment for depression, has been shown to be effective in numerous randomized placebo-controlled trials. Although this intervention is more effective than waitlist control group and placebo conditions, a considerable number of clients do not respond to this approach. Newer approaches include techniques specifically tailored to this particular population. One of these techniques, social mishap exposure practice, is associated with significant improvement in treatment gains. We will describe here the theoretical framework for social mishap exposures that addresses the client's exaggerated estimation of social cost. We will then present clinical observations and outcome data of a client who underwent treatment that included such social mishap exposures. Findings are discussed in the context of treatment implications and directions for future research.

Keywords: exposure therapy, social mishap exposure, social anxiety disorder, CBT

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is one of the most common anxiety disorders in the U.S., with a lifetime and 12-month prevalence of 12.1% and 7.1%, respectively (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, Merikangas, & Walters, 2005). It is defined by a persistent fear of negative evaluation by others in social or performance situations (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) and is associated with significant impairment in occupational, academic, and interpersonal functioning (Hofmann & Otto, 2008; Ruscio et al., 2008). SAD is a heterogeneous condition, as individuals with SAD may vary in the kinds of people, places, and situations that cause fear. However, common fears include formal public speaking, speaking up in a meeting or class, and meeting new people (Ruscio et al.). It also appears that while these situations may differentially provoke anxiety for each individual, most clients with SAD share similar underlying core fears, such as being rejected, looking stupid or unintelligent, expressing disagreement or disapproval, and being the center of attention.

Theoretical Models of SAD

There is strong empirical evidence supporting a cognitive-behavioral model of SAD (Davidson et al., 2004; Heimberg, Dodge, Hope, & Kennedy, 1990; Heimberg et al., 1998). The cognitive-behavioral model proposes that SAD develops and is maintained by maladaptive cognitive and behavioral processes, which negatively reinforce avoidance strategies and contribute to a cycle of anxiety and avoidance (Clark & Wells, 1995; Rapee & Heimberg, 1997). The following discussion is based on the maintenance model developed by Hofmann (2007), which emphasizes the importance of social cost and social mishap exposures. A more detailed explanation of this model is described elsewhere (Hofmann, 2007). According to this model, an individual with SAD experiences apprehension upon entering a social situation because they perceive the social standards to be excessively high and experience doubt about being able to meet those standards. Once confronted with social threat, individuals with SAD experience heightened self-focused attention, in which attention is turned inwardly toward one’s internal physical sensations and anxious thoughts (Brozovich & Heimberg, 2008; Clark & McManus, 2002; Hofmann, 2000a). Self-focused attention simultaneously triggers a variety of other cognitive processes, including a negative self-perception (e.g., “I am such an inhibited idiot”), high estimated social cost (e.g., “It will be a catastrophe if I mess up this situation”), low perceived emotional control (e.g., “I have no way of controlling my anxiety”), and perceived poor social skills (“My social skills are inadequate to deal with this situation”). These processes, in turn, lead the client to anticipate a social mishap in which one actually does something to embarrass oneself, cause negative evaluation, or otherwise violate social norms. This expectation contributes to the use of avoidance strategies and safety behaviors to cope with the anxiety and to avoid the feared outcome, which leads to post-event rumination about one’s performance in a social situation (Clark & Wells, 1995). The rumination and avoidance behaviors ultimately feed back into continued apprehension in social situations.

An important reason why SAD is maintained in the presence of repeated exposure to social cues is because individuals with SAD engage in a variety of avoidance and safety behaviors to reduce the risk of rejection (e.g., Wells et al., 1995). These avoidance tendencies, in turn, prevent patients from critically evaluating their feared outcomes and other catastrophic beliefs, leading to the maintenance and further exacerbation of the problem. Social mishap exposures directly target the patients’ exaggerated social cost by helping patients confront and experience the actual consequences of such mishaps without using any avoidance strategies.

Social Mishap Exposures

Consistent with the notion that clients with SAD overestimate the social costs associated with social mishaps, high estimated social costs have been proposed to be an important mediator of treatment change (Hofmann, 2000b). This hypothesis has been subjected to empirical testing, and substantiated in a treatment outcome study that compared cognitive-behavioral group therapy, exposure therapy (without explicit cognitive intervention), and a wait-list control group (Hofmann, 2004). It was found that changes in estimated social costs mediated treatment change between pre- to posttreatment in the two active treatment conditions (Hofmann, 2004). These empirical findings therefore support the utility of social mishap exposures in addressing this overestimation of costs associated with a social mishap. This is accomplished by having the client behave in a way that causes a social mishap by purposefully violating the client’s perceived social norms (e.g., singing in a subway).

The difference between social mishap exposures and exposure practices that have been typically used in cognitive-behavioral therapy protocols for SAD is that social mishap exposures cause clients to experience the feared outcomes that they try so hard to avoid by clearly appearing incompetent, crazy, obnoxious, and so on. Standard exposure practices of patients with SAD are typically designed to make patients realize that social catastrophes are unlikely to happen, and that patients are able to handle socially challenging situations despite their social anxiety (e.g., Heimberg et al., 1990, 1998). In contrast, the goal of the social mishap exposures is to purposely violate the patient’s perceived social norms and standards in order to break the self-reinforcing cycle of fearful anticipation and subsequent use of avoidance strategies. Patients are asked to intentionally create the feared negative consequences of a feared social situation. As a result, patients are forced to reevaluate the perceived threat of a social situation after experiencing that social mishaps do not lead to the feared long-lasting, irreversible, and negative consequences. A more detailed description of this model is presented in Hofmann (2007).

Early data suggest that treatment protocols that incorporate social mishap exposures show considerably greater efficacy than traditional CBT protocols, which are typically associated with only moderate effect sizes (e.g., Hofmann & Smits, 2008). Other, more recent studies that include social mishap exposures (among other techniques) report considerably larger efficacy rates. For example, Clark and colleagues (2003) reported effect sizes ranging between 1.41 (pretest to posttest) and 1.43 (pretest to 12-month follow-up; Clark et al.). Similar efficacy data (pre-post effect size of 1.54) have been found in an early pilot trial (Hofmann & Scepkowski, 2006).

Obviously, social mishap exposures are not the only aspect that distinguishes traditional CBT protocols from more modern approaches (Hofmann, 2012). Depending on the specific treatment protocol, other aspects include strategies for attention retraining, changes in self-perception, and post-event rumination. However, in-vivo social mishap exposures are the most obvious differences to traditional CBT approaches, which have primarily employed in-session role-play situations with the goal to identify and replace maladaptive general automatic thoughts. The purpose of the current paper is to present a case example from a group cognitive-behavioral therapy protocol that emphasizes social mishap exposures, and to discuss the benefits and challenges associated with its successful implementation. The case that follows discusses a treatment-seeking individual who presented to an outpatient clinic specializing in the treatment of mood and anxiety disorders.

Method

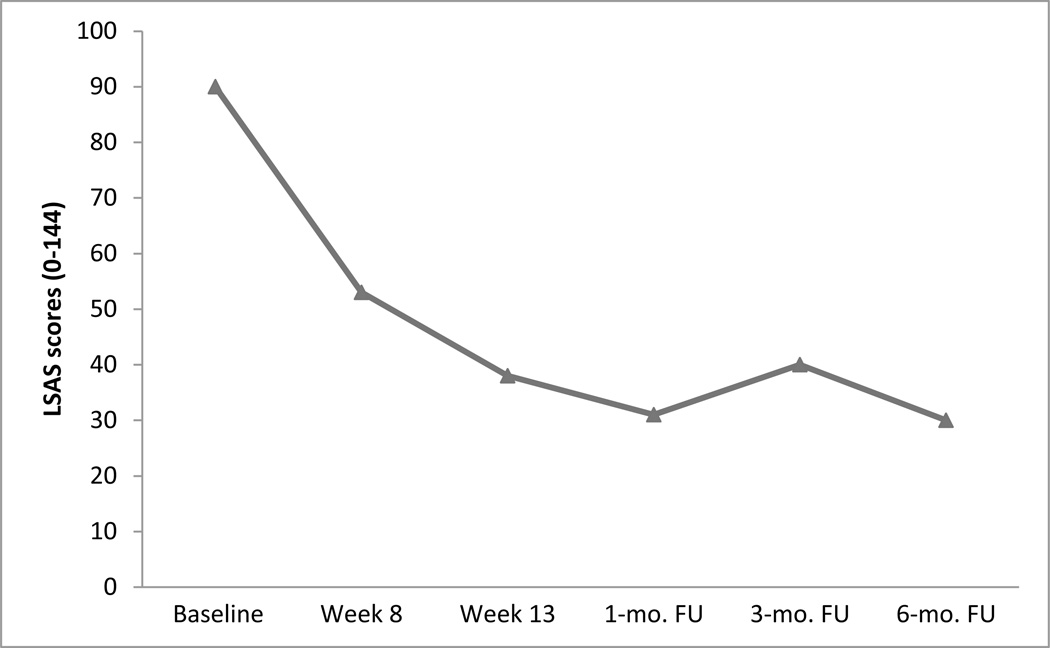

The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule (ADIS-IV; DiNardo, Brown, & Barlow, 1994) was administered at the intake evaluation. The ADIS-IV is a semistructured clinical interview that assesses mood and anxiety disorders according to DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria. The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS; Liebowitz, 1987) is a 24-item clinician-administered measure that assesses fear and avoidance of social situations (each rated on a 0- to 3-point scale with a range of total scores from 0 to 144) in the past week. The LSAS has been validated in clinical samples, and has high internal consistency (Heimberg et al., 1999). The LSAS was administered at every session throughout the course of treatment, and also at six major time points: baseline, Week 8, posttreatment, 1-month follow-up, 3-month follow-up, and 6-month follow-up.

Case Example

Mary1 was a 41-year-old married, Caucasian, insurance company analyst, who lived with her husband and two children. She came to the clinic seeking outpatient psychotherapy for her social anxiety. She presented with primary concerns about having suffered from anxiety throughout her life. She reported “always feeling awkward and self-conscious in groups,” and not knowing what it was until she read more about social anxiety in online help forums. Mary described her social anxiety as being at its worst when meeting new people in unstructured social gatherings, such as parties and work events, and she described the anticipatory anxiety to be so crippling that she would often turn down invitations. She reported feeling nervous about what to say, asking too many questions, and not feeling like herself. Mary’s anxiety had affected her life in many ways. For example, in college she had majored in mathematics to avoid courses that involved formal presentations; she had lost jobs; and, ultimately, she had chosen a career that involved limited social interactions. When Mary was asked what she was concerned would happen in these situations, she could not initially give an answer, but later responded that she was worried that others would judge her negatively, reject her or hurt her feelings. She further explained that her worst fear was that she would alienate everyone, even those who were close to her.

Mary described recent concerns about not performing well at work due to extreme distress when preparing for group meetings and presentations and extreme anxiety making work-related phone calls. During her assessment, it was gleaned that Mary was worried that she was going to get fired from her job because she had put off making some important phone calls, and clients had called her supervisor to complain. She described being concerned that she would be perceived as incompetent or unintelligent by clients and coworkers. Mary also had concerns about wanting to be more involved in her children’s lives at school because her husband worked much longer hours, but she was very apprehensive about attending parent-teacher conferences, parent-teacher association meetings, and making small talk with other mothers at her sons’ sporting events and school concerts. She described being particularly afraid of unstructured small talk with same-age parents or teachers because they would think she was awkward. Mary explained that she feared other mothers perceiving her as an uninvolved and bad parent. She also reported severe avoidance of her children’s extracurricular events, with the exception of dropping them off and picking them up.

In addition, Mary described residual symptoms of depression that never resolved after having lost her job 2 years ago. She had been working as a research analyst at a local bank, and had been fired due to the bad economy as well as poor reviews from clients. She reported feeling like she had lost interest in many activities that she used to enjoy, such as shopping and seeing friends, and has been feeling excessively guilty and doubtful of her ability to hold her current job. Mary reported not having ever received cognitive-behavioral therapy for either her depression or social anxiety concerns, but that she had tried supportive therapy with a variety of health-care professionals, including counselors and licensed social workers. Last year, Mary visited a psychiatrist to receive psychopharmacological interventions for her depression, which she reported being effective.

Based on information obtained from her baseline assessment, Mary received a primary diagnosis of SAD, generalized subtype, and a diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD), in partial remission. She had no other comorbid psychiatric disorders, but reported a family history of MDD. She had also been taking Wellbutrin (200 mg) for a year for her depression, which she discontinued through a psychiatrist-guided taper prior to starting group treatment. Her baseline LSAS score of 90 reflected a severe level of SAD.

Treatment Procedure

The treatment consisted of 12 weekly, 2.5-hour sessions of group cognitive-behavioral therapy with four to six members in total. The protocol was implemented by two therapists, master’s-level doctoral candidates, who followed the Hofmann and Otto (2008) treatment manual. Week-to-week LSAS scores were determined by meeting separately with a trained independent evaluator before the start of each group.

Sessions 1–2: Psychoeducation and Cognitive Restructuring

The first session consisted of an introduction of cotherapists and group members and their reasons for seeking treatment. Psychoeducation about the nature of SAD as a learned habit and the adaptive aspects of anxiety were presented and discussed. An overview of treatment was presented, with an introduction to the primary treatment techniques, which included cognitive restructuring and in-vivo exposures. The session concluded with identification of automatic negative thoughts related to attending group treatment specific to each client, and assignment of thought records (e.g., monitoring of such automatic thoughts) for homework.

Session 2 began with a review of the homework and an invitation from group members to share their thought records. The majority of the session focused on presenting the exposure rationale to the group by discussing the role of avoidance in perpetuating the cycle of anxiety. Examples of safety behaviors and other avoidance behaviors were discussed by using specific recent examples. The short-term and long-term consequences of these avoidance behaviors for the maintenance of the disorders were discussed. The session concluded with a discussion of concerns and questions about the start of public speaking exposures at the next week’s session. For homework, clients were asked to generate a hierarchy of feared social situations for use throughout treatment.

Mary attended the group along with four other clients. The other members varied in age, gender, occupation, and SAD symptom severity. At the first two sessions, Mary engaged in the discussion and appeared to relate to other group members’ experience of SAD. Similar to other members, Mary described strong physiological reactions (e.g., racing heartbeat and sweaty palms) to anticipating an important class presentation or work meeting; she identified jumping to conclusions as a major cognitive distortion that emerged for her.

Sessions 3–7: In-Session Exposures

Sessions 3 to 7 consisted primarily of conducting in-session public speaking exposures, in which each group member gave a 3-minute speech on an impromptu topic that he or she had rated highly on a speech topics hierarchy. Specific behavioral goals were collaboratively agreed upon with the therapist at the start of the exposure to address elimination of safety behaviors during the exposure, as well as the individual client’s core fears. Incorporating social mishap during the speech exposure was introduced as a way to disconfirm negative beliefs about feared consequences. Furthermore, automatic thoughts about the speech were identified and challenged before and after the exposure. Speeches, conducted in front of the group, were videotaped to provide feedback to clients.

For homework, group members were requested to repeat their in-session speech exposures in front of the mirror each day three times in a row. The mirror exposures were used to address clients’ self-focused attention by allowing them to receive live feedback on their appearance (akin to videotape feedback during the session), and to give them a chance to engage in the repeated exposure model for anxiety reduction.

Mary described experiencing significant anticipatory anxiety leading up to these sessions, and even admitted to almost skipping a session to avoid giving an impromptu speech. Her speech exposures were particularly useful and relevant for the group presentations that she had to give as part of her job. Mary’s primary fear in this domain was running out of things to say, which would cause her to engage in safety behaviors such as limiting eye contact with the audience and freezing up in front of the group to minimize attention on her. As a result, while these first few in-session public speaking exposures were structured similarly to the more traditional SAD group treatment exposures, the concept of purposefully experiencing social mishaps was introduced very early on (typically by the second or third in-session exposure) to target these avoidance behaviors. In collaboration with the other group members and Mary, the therapist generated specific exposure tasks to provide Mary with an opportunity to examine the actual consequences of what she considered to be social mishaps. For example, during Session 5, Mary was asked to give a 3-minute speech about cloning (of which she had little knowledge), and her specific goals were (a) to make eye contact with every member of the audience at least once; (b) to stop speaking suddenly in the middle of her speech for a long pause and to count 5 “Mississippi” before resuming; and (c) to pace back and forth across the room during the entire speech. In accordance with the research on high perceived social standards and high estimated social costs associated with the speech, Mary collaboratively designed an experiment with the therapists to test how high the social standards and social costs were for the speech and to see what would happen if she did run out of things to say. Mary reported an anticipatory anxiety of 80 (on a 100-point scale of subjective units of distress, or SUDS), a peak anxiety of 80, and a final anxiety of 45 at the end of the exposure. She described experiencing significant anxiety when she stopped speaking at first, but that it gradually came down over time. She stated at the end of the exposure that pausing during the speech was not as bad as it sounded at first. Upon reviewing the videotape feedback, Mary noted that the person in the video did not actually look that anxious during the long pause. This was an important component of treatment for her, as she mentioned later that she was shocked by the discrepancy between how she looked and how anxious she felt on the inside.

Speech exposures can be used to target other fears by reevaluating the patient’s estimated social costs. For example, clients who fear looking silly during the speech can be asked to put on a costume or prop, such as an attention-grabbing wig or witch’s hat. Those who fear appearing unintelligent may say something factually incorrect or mispronounce a word during the speech. Those who fear that they will stutter can intentionally stutter during the speech. Speech exposures have also been used in tandem with interoceptive exercises for individuals who fear the physiological sensations that emerge in anticipation of or during the speech. Those individuals would conduct interoceptive exercises (e.g., induced hyperventilation for shortness of breath, running in place for racing heartbeat and sweating) for 1 minute before the start of the speech.

Sessions 8–11: In-Vivo Mishap Exposures

Sessions 8 to 11 involved targeted in-vivo mishap exposures that were further tailored to the individual client’s core fears. The goals for the exposures were collaboratively discussed and agreed upon with the therapists at the outset. Social costs were incorporated into each exposure to target specific core fears of the individual client. In addition, automatic thoughts about the exposures were identified and challenged before and after the exposure. When group members returned from the exposures, the therapists led a discussion of whether each exposure was successful by reviewing the clients’ goals.

Mary’s in-vivo mishap exposures were designed to target her fears of inconveniencing others, being the center of attention, and being thought of as unintelligent. To address her fear of inconveniencing others, the therapists worked with Mary to design an exposure in which she negotiated a romantic vacation package at a nearby five-star hotel. Her goals were to ask for tickets to a ballgame, for rose petals to be strewn on the bed, and for a horse-drawn carriage tour of the city. At the end of stating those three requests, her goal was to obtain an itemized list with the final price, negotiate the price, and then reject the offer because she “changed her mind” without apologizing or giving any excuses. She described having automatic thoughts that she would get kicked out of the hotel, and that the concierge staff would roll their eyes at her. Mary’s anticipatory anxiety was a 90, her peak anxiety was a 90, and her final anxiety rating was a 40. Upon completing her exposure, she stated that she was surprised by the concierge’s accommodating nature, despite her outrageous requests, and that she did not receive the kind of negative response she had anticipated by the concierge staff. She met all of her goals and left the exposure with a sense of accomplishment for minimizing any use of safety behaviors (e.g., apologizing excessively for turning down the offer).

Other exposures that Mary conducted in subsequent sessions addressed similar fears: interrupting a group of people in a restaurant to practice a toast for a maid-of-honor speech (targeting inconveniencing others and being the center of attention); asking strangers in a bookstore to read the back cover of a book because she did not know how to read (targeting being thought of as unintelligent); and, while wearing bandages on her face, asking people on the street if they were “Carl Smith” because his car was being towed (targeting inconveniencing others, being the center of attention, and being thought of as weird).

Mary was assigned between-session in-vivo exposures to practice the effects of repeated exposure. She was encouraged to be creative, be concrete in specifying the behavioral goals of the exposures, and to try out other group members’ exposures. During the course of treatment, opportunities arose for Mary to make important phone calls at work and attend parent meetings at her children’s school. She had assigned goals for herself that minimized the use of safety behaviors, such as not procrastinating and initiating introduction of herself to at least one individual. Mary reported that these between-session exercises were essential to her progress, as they translated her therapeutic work to her real-life social situations and contexts. As stated previously, these exposure exercises should specifically challenge the patient’s social cost estimates (e.g., walking around with toilet paper hanging out of the shirt, buying and minutes later returning the same book, walking on a busy street with the zipper of the pants wide open, spilling water in a restaurant, asking a random woman on a street out on a date) to be most effective. When conducting these social mishap exposures, it is important to clearly define the goal of the exposure situation and not to link the success or goal of the exposure to the patient’s anxiety (i.e., “I want to do it nonanxiously” is not an acceptable goal). Instead, the goal should be linked to specific behaviors that allow the patients to test the anticipated consequences of the social mishaps. It is essential that patients refrain from avoidance or safety behaviors, such as apologizing, or any other behavior that might lessen the patients’ anxiety in the situation. For this reason, it is advisable to provide detailed instructions to the patients to give them no room to engage in any such avoidance behaviors. Table 1 provides further examples of social mishap exposures that clinicians may utilize in treatment.

Table 1.

| Examples of Social Mishap Exposures |

|---|

|

Our research group has filmed a series of treatment sessions to exemplify various aspects of the intervention. These can be found online at the Boston University Psychotherapy and Emotion Research Laboratory (http://www.bostonanxiety.org/treatmenttools.html). In particular, the following video clips depict three treatment phases germane to the current paper: Video 1 demonstrates how to set up for an in-vivo exposure (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f4CJ_njM7r8&feature=youtu.be); Video 2 demonstrates how to conduct a social mishap exposure (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=90xMSaNqjEw&feature=youtu.be); and Video 3 demonstrates the postprocessing of a social mishap exposure (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jz0pQhYRcgs&feature=youtu.be).

Session 12: Relapse Prevention

The treatment concluded with a discussion of relapse prevention strategies. Clients reviewed their progress, discussed areas of improvement, assisted each other in detecting warning signs, and generated ways to maintain their progress. Similar to the recommendations for continued use of other treatment components (e.g., cognitive restructuring techniques, approach to feared situations), ongoing use of social mishap techniques posttreatment were suggested in those cases where overestimated social cost and fear of social norm violation remained a primary issue. For instance, Mary was encouraged to continue targeting her fear of being the center of attention by engaging in behaviors for which she thought she would be negatively judged. She was encouraged to try out social mishap exposures that other group members had engaged in during the course of treatment to target this fear (e.g., wearing bright colored articles of clothing, talking loudly into her cell phone in a crowded area, and opening her umbrella indoors).

Summary of Treatment

At the end of treatment, Mary’s LSAS score decreased to 38, which represented a 57.8% reduction of SAD symptoms from baseline. Mary continued to improve and maintain her progress following acute treatment, as her LSAS scores indicated further improvements in SAD symptom severity and maintenance of such progress even 6 months later. Please see Figure 1 for a visual representation of Mary’s outcome data at each time point.

Figure 1.

Outcome data for case of Mary

Discussion

Although Mary improved in a clinically meaningful way by the end of the treatment, she presented certain challenges to the therapists who led her group. One primary difference in Mary’s case compared to the other group members was that Mary had a longer duration of illness (she was the oldest member of the group) and she had a higher baseline severity of symptoms than the other members. She had therefore developed highly evolved and idiosyncratic avoidance strategies. For example, it was not until the therapists conducted a functional analysis during treatment that they discovered that Mary’s overdelegation of work (related to making phone calls) to the administrative assistants in the office was an avoidance strategy couched in her mind as a justification for enhancing her efficiency at work. In other cases, clients have entered treatment with significant stigma about seeking treatment, and have felt initially resistant to in-vivo exposures because of a fear of “being discovered” as having social anxiety by people in the area where they were engaging in exposure exercises. These thoughts had to be addressed directly through cognitive restructuring to motivate members to attempt the exercise assigned, and were even tested as predictions in the exposures. It was therefore challenging for the therapists to allot relatively equal amounts of time reviewing homework and exposures with each client when some clients needed inordinately more time. There were limitations of the current study that deserve mention. Some of the limitations apply for any treatment that is administered in a group rather than individual format. Although there tends to be less emphasis on an individual client in a group treatment, the current protocol allowed for meaningful tailoring of the treatment to an individual’s needs and core fears.

Our clinical experience is that treatments that involve social mishap exposures are not associated with greater dropout rates than traditional CBT. This is consistent with other studies utilizing similar social mishap exposure techniques (Clark et al., 2003). This is somewhat surprising given the highly unpleasant nature of the exposure tasks. A group format may provide additional motivation for single patients. At the same time, a group format provides less flexibility to treat comorbid conditions in the context of this protocol. Consistent with research indicating that SAD rarely occurs in isolation (Wittchen & Fehm, 2001), a majority of the clients in the group had other comorbid clinical disorders. Although Mary’s depression remained in partial remission during the course of treatment, and in light of research showing the negative impact that comorbidities such as depression have on SAD treatment outcomes (Marom, Gilboa-Schechtman, Aderka, Weizman, & Hermesh, 2009), the group treatment for SAD may not have been appropriate had she experienced another depressive episode. It is also worth noting that the cases presented in the current study represented a highly motivated subset of individuals who participated in our group treatments, which may not be generalizable to the larger population of clients with SAD. This worked to our advantage because they were not only engaged in the treatment, but they also served as cotherapists in the group by encouraging other group members to engage in treatment. We recommend that future treatment studies incorporate social mishap exposures and further investigate their relative efficacy by directly comparing them to more traditional exposures. Additionally, although in our experience all patients benefit to some extent from engaging in social mishap exposures, it is important to systematically examine whether particular subsets of patients benefit more than others (e.g., patients of certain age groups, clinical presentations, motivation levels).

Supplementary Material

Research Highlights.

Social mishap exposures target patients’ exaggerated social cost by confronting them with the actual consequences of such mishaps.

Early data suggest that treatment protocols that incorporate social mishap exposure show considerably greater efficacies than traditional CBT protocols.

The current study provides the course and outcome of a group-based protocol for social anxiety and provides a case example outlining how social mishap exposures can be incorporated throughout treatment.

Social mishap exposures should be specifically tailored to the core fear of the patient.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Client name and other identifying information have been changed to protect client confidentiality.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. text revision. [Google Scholar]

- Brozovich F, Heimberg RG. An analysis of post-event processing in social anxiety disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:891–903. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM, Ehlers A, McManus F, Hackmann A, Fennell M, Campbell H, Louis B. Cognitive therapy versus fluoxetine in generalized social phobia: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:1058–1067. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM, McManus F. Information processing in social phobia. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51:92–100. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM, Wells A. A cognitive model of social phobia. In: Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hope DA, Schneier FR, editors. Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1995. pp. 69–93. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JRT, Foa EB, Huppert JD, Keefe FJ, Franklin ME, Compton JS, Gadde K. Fluoxetine, comprehensive cognitive behavioral therapy, and placebo in generalized social phobia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:1005–1013. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.10.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNardo PA, Brown TA, Barlow DH. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Client Interview Schedule. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Heimberg RG, Dodge CS, Hope DA, Kennedy CR. Cognitive behavioral group treatment for social phobia: Comparison with a credible placebo control. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1990;14:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Heimberg RG, Horner KJ, Juster HR, Safren SA, Brown EJ, Schneier FR, Liebowitz MR. Psychometric properties of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale. Psychological Medicine. 1999;29:199–212. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hope DA, Schneier FR, Holt CS, Welkowitz LA, Klein DF. Cognitive behavioral group therapy vs phenelzine therapy for social phobia: 12-week outcome. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:1133–1141. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.12.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG. Self-focused attention before and after treatment of social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000a;38:717–725. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG. Treatment of social phobia: Potential mediators and moderators. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2000b;7:3–16. doi: 10.1093/clipsy/7.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG. Cognitive mediation of treatment change in social phobia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:392–399. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG. Cognitive factors that maintain social anxiety disorder: A comprehensive model and its treatment implications. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2007;36:193–209. doi: 10.1080/16506070701421313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG. An introduction to modern CBT: Psychological solutions to mental health problems. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Otto MW. Cognitive-behavior therapy for social anxiety disorder: Evidence-based and disorder-specific treatment techniques. New York: Routledge; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Scepkowski LA. Social self-reappraisal therapy for social phobia: Preliminary findings. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2006;20:45–57. doi: 10.1891/jcop.20.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebowitz MR. Social phobia: Modern problems in pharmacopsychiatry. 1987;22:141–173. doi: 10.1159/000414022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marom S, Gilboa-Schechtman E, Aderka IM, Weizman A, Hermesh H. Impact of depression on treatment effectiveness and gains maintenance in social phobia: A naturalistic study of cognitive behavior group therapy. Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26:289–300. doi: 10.1002/da.20390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM, Heimberg RG. A cognitive-behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35:741–756. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscio AM, Brown TA, Chiu WT, Sareen J, Stein MB, Kessler RC. Social fears and social phobia in the USA: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38:15–28. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells A, Clark DM, Salkovskis P, Ludgate J, Hackmann A, Gelder M. Social phobia: The role of in-situation safety behaviors in maintaining anxiety and negative beliefs. Behavior Therapy. 1995;26:153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Fehm L. Epidemiology, patterns of comorbidity, and associated disabilities of social phobia. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2001;24:617–641. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70254-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.