Abstract

As urbanization rates rise globally, it becomes increasingly important to understand the factors associated with urban out-migration. In this paper, we examine the drivers of urban out-migration among young adults in two medium-sized cities in the Brazilian Amazon—Altamira and Santarém—focusing on the roles of social capital, human capital, and socioeconomic deprivation. Using household survey data from 1,293 individuals in the two cities, we employ an event history model to assess factors associated with migration and a binary logit model to understand factors associated with remitting behavior. We find that in Altamira, migration tends to be an individual-level opportunistic strategy fostered by extra-local family networks, while in Santarém, migration tends to be a household-level strategy driven by socioeconomic deprivation and accompanied by remittances. These results indicate that urban out-migration in Brazil is a diverse social process, and that the relative roles of extra-local networks versus economic need can function quite differently between geographically proximate but historically and socioeconomically distinct cities.

Keywords: Migration, Urbanization, Brazil, Internal migration, Family networks

Introduction

In 2000, nearly half of the world’s population lived in urban areas, and by 2030 over 60 % of the global population is expected to live in cities (Cohen 2006). As the world becomes increasingly urbanized, the character of internal migration has the potential to fundamentally change from one dominated by rural–urban migration to one in which urban out-migration plays a central role. While the past three decades have seen a revolution in research on migration in the developing world, most of it has focused on the predominant flows, those from rural to urban areas. This paper builds on the theoretical advances of recent decades and contributes to the small but growing literature on urban out-migration.

Past research in several developing countries has argued that differences exist in the correlates of urban and rural out-migration (Fussell and Massey 2004; Reed et al. 2010; Shefer and Steinvortz 1993). These studies indicate that macro-level factors (e.g. unemployment rates) and micro-level factors (e.g. educational attainment) impact urban and rural out-migration streams differently and that migrant networks function differently in large cities versus small cities and villages. Further research into how drivers of migration and migrant selectivity operate in urban settings will help shed more light on the factors associated with urban out-migration, the ways in which migration processes differ between urban and rural areas, and the future migration streams that developing countries might anticipate.

We focus our study on Brazil, which has historically been characterized by high levels of internal migration (Browder and Godfrey 1997). Specifically, we concentrate on the Brazilian Amazon, a region that has quietly experienced steady urbanization for decades. In addition, the urbanization process in the Amazon region is fundamentally different from that in other parts of the country, as it is driven by natural resource extraction and agricultural settlement rather than by the growth of industry (Browder and Godfrey 1997). Data from the 2010 census indicate that 72 % of the population of the legal Amazon is concentrated in urban areas (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística [IBGE] IBGE 2012). In addition, there is evidence of high levels of inter-urban movement within the Amazon region, suggesting that urban networks may be an important driver of migration between the region’s cities (Costa and Brondizio 2009). Lastly, a study of urban in-migration to two different areas within the Amazon (the states of Rondônia and Pará) finds that the migration process is highly heterogeneous in the region (Browder and Godfrey 1997). We examine the heterogeneous nature of urban out-migration in the Amazon through an analysis of two medium-sized cities in the state of Pará—Santarém and Altamira.

These two cities provide distinct urban experiences within the Amazon. While Altamira had a population below 6,000 prior to the 1970s, Santarém has been a city of substantial size for hundreds of years (Alonso and Castro 2005; Prefeitura de Santarém 2012). Past literature suggests that differences in settlement history correlate with the extensiveness of intra- versus extra-city social networks, and we will examine this relationship empirically below. DaVanzo (1981) argues that intra-city social networks are an important component of location-specific capital, or the non-transferable assets that people accumulate in the places in which they live, while the extensive work of Massey and colleagues (for example, Massey and García España 1987; Massey and Aysa 2005; Palloni et al. 2001) shows the importance of extra-local networks in migration. Santarém is more likely to contain families who have lived in the city for many generations, while the majority of families in Altamira have migrated to the region within the past 40 years. These two cities, therefore, capture a large range of local and non-local social connections. There are also socioeconomic differences between the cities that we expect to affect the level and selectivity of migration. Santarém is a larger city than Altamira but has higher levels of poverty, inequality, and unemployment during the study period (IBGE 2011; WinklerPrins 2002).

Our objective is to understand how drivers of out-migration—specifically extra-local family networks, human capital, and demographic and socioeconomic characteristics—function differently in the two cities. We predict that an individual’s extra-local ties will act as a stronger driver of out-migration from Altamira than from Santarém due to Altamira’s more recent settlement history. In addition, we expect that migrants from Santarém will be driven more by socioeconomic deprivation than those from Altamira due to Santarém’s less favorable economic environment. Indeed, we find that in Altamira, migration tends to be an individual-level opportunistic strategy fostered by extra-local networks, while in Santarém, migration tends to be a household-level income generation strategy undertaken by individuals from more socioeconomically vulnerable households.

Theoretical Framework and Conceptual Model

In this section we review migration theories, focusing on economic theories (neoclassical theory and the new economics of labor migration) as well as theories on the role of migrant networks. In each case, we focus on the theoretical predictions regarding the importance of individual- and family-level characteristics for out-migration and on how theories might suggest differences in the patterns of out-migration between the two cities. Important factors in these theories that change over time or across large spatial or political units (e.g. destination wage rates, macroeconomic policy) are constant across our sample, and year-to-year variation in migration rates captures a mix of many such factors. We discuss the importance of these spatial, political, and temporal factors in the description of the sites but do not suggest that our models can speak to their impact on migration in the two cities.

Economic Theories of Migration

Neoclassical migration theory focuses on migration as an individual-level strategy to maximize income and economic opportunities (Massey et al. 1993; Todaro 1969) and, therefore, points to the importance of individual and community characteristics that impact income and employment in the origin community and in potential destinations. According to neoclassical theory, an individual considers the potential income gains in a destination area and is predicted to migrate if those economic gains, discounted over time, are sufficiently higher than the earnings in the origin area (White and Lindstrom 2005). Migration is viewed as an investment accompanied by costs (e.g. costs of moving, costs of finding housing and employment in the destination, and emotional costs of leaving one’s home and family), and it is assumed that among migrants, these costs are outweighed by the income returns in the destination area or by returns to the human capital acquired in the destination (Sjaastad 1962). Income returns are determined by both the wage differential and the probability of finding a job in the destination area (Todaro 1969). Therefore, neoclassical theories predict that migrants may move to cities and temporarily work in the low-paying informal sector with the knowledge that they will eventually find higher paying formal sector employment. Traditional formulations of this theory assume a 100 % probability of employment in the origin because migrants are assumed to come from a rural sector in which labor is readily incorporated (though not well-compensated) in the familial agricultural sector. To adapt this approach to urban out-migration, we consider how individual characteristics and the context of the city influence the probability of employment in each of our study communities.

The new economics of labor migration (NELM) perspective builds off of and departs from neoclassical theory, arguing that labor migration in low- and middle-income countries results not from effective functioning of labor markets but instead from non-functional credit and insurance markets. Migration serves as a household-level strategy to diversify income sources and increase household cash income through remittances received by the migrant members of the household (Hoddinott 1994; Stark and Bloom 1985; Stark and Lucas 1988; Taylor 1999). According to NELM theory, households send migrants as a cooperative strategy to insure against loss of income due to local economic or environmental shocks (e.g. a surge in food prices or crop failure due to drought) and to generate additional income to invest in local production activities in light of imperfect credit markets. Migrants tend to be either the household heads or children of the household heads (versus the spouse or extended kin), who pursue new employment opportunities in destination areas and remit back to their families in the origin households either on a regular basis to provide income or in response to an origin community economic shock (Taylor and Martin 2001). In this approach, as in the neoclassical approach, earning power in destinations is important for the access to cash, but the covariance of wages and shocks between origin and destination is also important. Ideally, migrants move to an area where the economy is free from the shocks or independent of the economic conditions in the home community.

Remittances, an implicit component of NELM theory, assume a level of cohesiveness and trust between migrants and their family members who remain in the origin communities (Sana and Massey 2005). Stark and Lucas (1988) argue that migration and its associated remittances serve as part of a contractual arrangement between family members. The migrant may receive support from the family during the initial period after migration when employment opportunities are uncertain or while obtaining schooling, and the family is expected to receive support from the migrant once the migrant has established him or herself in the destination area’s employment market. In addition, there is evidence that the propensity for an individual to remit depends on the level of economic need in the origin household, with poorer households more likely to receive remittances than wealthier households (Osili 2007; VanWey 2004). Understanding how the propensity to remit differs between the two study cities as well as by individual- and household-level characteristics further helps us to characterize the urban out-migration stream in the Amazon.

Migrant Network Theories

Theories on migrant networks can be used to explain both migration decisions and destination choices (Deléchat 2001; Massey 1990; Massey and Aysa 2005; Massey and García España 1987; Winters et al. 2001). The presence of migrant networks (family members and friends) in a destination area substantially reduces the costs of migration, as family and friends act as sources of information and resources to a potential migrant. Most of the work in this tradition has focused on parents, children, spouses, or community members (e.g. Cerrutti and Massey 2001; Kanaiaupuni 2000; Massey 1987; McKenzie and Rapoport 2007). There is also clear evidence that sibling networks play an important role in fostering migration. Massey and Aysa (2005) compare the relationship between migrant networks and U.S. migration from six Latin American countries. They find that in four of the six countries, having a sibling migrant in the U.S. significantly increases a household head’s odds of migrating to the U.S. for the first time. Palloni et al. (2001) also find evidence in support of sibling networks in the case of Mexico–U.S. migration. They find that having a migrant older sibling reduces time to migration, lessens the likelihood of an individual not migrating by age 30, and lowers the age of first migration. We are able to draw on this work and compare the relationship between sibling migration and own migration to that of parent migration and own migration. While our study does not explicitly test migrant network theory in its strictest sense, we take the notion of family networks as extra-local social capital and combine it with DeVanzo’s (1981) theory on location-specific capital in order to test the role of extra-local family networks in fostering urban out-migration. We diverge from migrant network theory because an individual’s extra-local networks may or may not be composed of friends and family who migrated from the origin area. As such, we examine how an individual’s extra-local networks—measured by whether an individual was born outside of the study city, whether his or her parents were born outside of the study city, and whether his or her siblings live outside of the study city—as well as an individual’s location-specific capital—measured by the number of years his or her parents have lived in the study city—encourage or hinder migration.

Studies of internal migration in Mexico (Davis et al. 2002) and of internal rural–urban migration in Thailand (Garip 2008) show that the type and strength of network ties is important for predicting migration and destination selection. Davis et al. (2002) argue that migration networks must be disaggregated, and Garip (2008) goes on to hypothesize about the information contained in different networks. She argues that family ties in this context generally serve as information on low-paying agricultural or construction opportunities, while community ties to other young migrants offer information on higher wage opportunities in cities. In addition, a study among smallholder farmers in rural Santarém finds that individuals with a close family member or friend working off of the farm have increased likelihoods of finding off-farm work (VanWey and Vithayathil 2012) and a study in the Ecuadorian Amazon finds that the number of migrants within an individual’s household strongly predicts one’s likelihood of migration (Barbieri et al. 2009). These studies indicate that close extra-local networks influence labor mobility in the Amazon region, and we suggest that part of the variation in information provided by family ties reflects the life course nature of networks. That is, potential migrants are likely to get information on high-probability but lower status jobs from networks through parents, and information on lower probability but potentially higher status jobs from siblings and age-peers (from own past migrations).

As suggested above, in an urban origin, networks also matter for wages and probability of employment in the origin (and therefore the value of not migrating). We assume that social network ties in the origin community (e.g. family members living there for a long time) operate as a form of location-specific social capital and have the potential to reduce the probability of migration. This effect, or the balance between the importance of local ties and ties to destinations, could depend on city size. Regarding Mexico-U.S. migration, Fussell and Massey (2004) test the assumption that the impact of migrant networks on an individual’s likelihood of migration functions differently in small communities versus large cities. They find that cumulative causation functions as a mechanism sustaining Mexico-U.S. migration in rural communities and small cities but does not function in large urban areas (cities with 75,000 or more inhabitants) because social networks are more diffuse in these settings. They do, however, still find an important role for strong family networks in migration out of large cities. Our study does not contain adequate variation in city size to explicitly test the impact of city size, but we are able to examine the differences in the importance of networks between two cities and speculate on the social and economic processes underlying these differences.

Study Area

The state of Pará experienced dramatic population growth during the Brazilian military government’s Amazon settlement scheme in the 1970s, which sought to promote development of the interior of the country and alleviate poverty in the Northeast region (Alonso and Castro 2005; Browder and Godfrey 1990; Fearnside 1984; Yoder and Fuguitt 1979). This brought large numbers of people to Pará, particularly those from drought-prone Northeastern Brazil, with the offer of opportunities to develop rural agricultural land, leading to the growth of urban areas in the region (VanWey et al. 2007). Between 1970 and 1996, the population in Pará more than doubled, from 2.2 million to 5.5 million (Perz 2002). Yet, by the 1990s, migration shifted from predominantly in-migration to the Amazon from other regions of Brazil to intraregional migration within the Amazon (Perz et al. 2010).

Figure 1 shows the region of Pará encompassing our two study cities. The area is located roughly in the center of Pará, including the intersections of key north–south and east–west transportation corridors. The Amazon and Tapajós Rivers are historical access routes to the farther interior Amazon, including Manaus, the capital of Amazonas state and home to an international free trade zone. Santarém has historically capitalized on its location at the confluence of these two important rivers and, in modern times, on its location at the northern terminus of the BR-163, the key highway connecting the prosperous agricultural regions of the center-west of Brazil to the Amazon region. In addition, the Amazon River directly links Santarém with Manaus, a city with substantial employment opportunities. Altamira lies along the Xingu River and along BR-230, the Transamazon Highway, a centerpiece of the military government’s program of national integration undertaken in the 1970s. Altamira is relatively close to Belém, the capital city of Pará, which offers numerous educational opportunities. In addition, Altamira also lies in proximity to a number of smaller cities within Pará (e.g. Parauapebas and Paragominas), which offer employment opportunities in extractive industries.

Fig. 1.

Map of study cities, including main rivers, highways, and regional capitals

Each city has a long settlement history as well as recent demographic changes. Santarém has long-housed substantial populations and has been an economic center for a series of waves of extractive industries in the Amazon. Santarém experienced economic booms and busts associated with the rubber, jute, gold, and most recently soy industries (Prefeitura de Santarém 2013), and its strategic port location allowed for the development of Brazil nut and cacao export industries (Amorim 2000). Along with the economic booms associated with extractive industries came population growth. In addition, in 1934, the Ford Motor Company started a large rubber plantation in Belterra, located 48 km south of Santarém, attracting migrants to the area to work on the plantation (Russell 1942; Grandin 2009). Further, a massive drought in northeastern Brazil in 1958 led to the out-migration of millions of peasants from that region to other areas of Brazil including Santarém (Xavier et al. 1984; Rose 1980).

By 1970, Santarém had a population of 51,123, which grew to 111,023 in 1980 and 186,297 by 2000 (de Sá, da Costa, and de Oliveira Tavares de Sá et al. 2006). Today, the urban population (approximately 75 % of the county population) is approximately 294,000 (IBGE 2011). The current rural economic base is agriculture, mixing soy and rice production with large crops of manioc and related products. The urban economy is based largely on trade, services to regional populations, and government employment. While periodic booms have promised a transformed economy, Santarém remains a city with limited employment opportunities, and unemployment and underemployment are problems among the urban population (WinklerPrins 2002). The 2003 poverty rate in Santarém was 43 %, with a Gini coefficient for household income of 0.43 (IBGE 2011). These indicators are roughly equal to those for the state of Pará as a whole, which had a 2003 poverty rate of 43 % and a Gini index for household income of 0.44 (IBGE 2014).

Altamira was settled by missionaries in the 18th century (Umbuzeiro and Umbuzeiro 2012), but its less strategic location led to much slower population growth. It is situated just upstream of non-navigable rapids on the Xingu River, eliminating the possibility of it providing a stop on a waterway from the upper Xingu to the Amazon. Altamira remained a small town until the Brazilian government’s National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA) began a settlement scheme in the early 1970s, which sought to reduce landlessness and poverty as well as develop the interior of the country (Alonso and Castro 2005; VanWey et al. 2007). Through INCRA, families were settled in Integrated Colonization Projects (PICs), and Altamira alone received nearly 3,000 families during this period (Arruda 1978). Other settlers migrated into the area spontaneously to the settle unclaimed land. The Altamira settlement area, west of the city on the Transamazon Highway, was a model settlement founded in 1970 (Moran 1981).

In 1970, Altamira had a population of 5,374, but with the settlement scheme the population grew rapidly, to 26,911 in 1980 and 62,285 in 2000 (Alonso and Castro 2005). Today, the municipality has a population of 99,000, with 84,000 living in the urban area (IBGE 2011). The economy of Altamira centers on agriculture, livestock production, and agribusiness (Confederação Nacional de Municípios 2011). The region houses and processes a large herd of cattle and is home to cacao bean farms with the highest levels of productivity in the country (Comissão Executiva do Plano da Lavoura Cacaueira [CEPLAC]). Altamira also provides employment opportunities primarily in the service sector, but has slightly less unemployment and underemployment than Santarém. Poverty and inequality are also slightly lower in Altamira. The 2003 poverty rate was 41 %, with a Gini index for household income of 0.40 (IBGE 2011). Altamira is currently a city of rapid in-migration and development due to construction of the Belo Monte Hydroelectric Complex on the Xingu River. Construction began in 2011, after the period of data collection for this study, but there is evidence of increasing levels of in-migration as early as 2006 due to the expected demand for dam-related labor (Herrera and Moreira 2013). This recent in-migration is unlikely to affect our results because our study is focused on adult children of respondents. Most dam-related migrants are young adults seeking employment and would, therefore, not have adult children. It remains to be seen how the influx of migrants related to the construction of Belo Monte will affect the dynamics of mobility in the region.

Data Collection and Model Specification

This study utilizes survey data from a household survey of 1,000 households in urban Altamira and Santarém (500 households from each city). Data were collected in 2009 in Santarém and 2010 in Altamira. In each city, we drew a stratified random sample of households. We first selected ten census tracts with probability proportional to size (number of households).1 In each census tract, we then created a sampling frame by physically enumerating all occupied houses in the tract. From this frame, we surveyed 50 randomly selected households, creating a self-weighting sample. Households were surveyed in-person by local interviewers and university students from the Universidade Estadual de Campinas (Unicamp) in São Paulo. Because parts of the survey focused on reproductive histories, interviewers sought to interview the female head of household. In cases in which there was no female head, the male household head was interviewed. The interview covered standard sociodemographic information, with special effort devoted to the migration history of the female and male heads of household and the locations of and relationships with non-coresident children and parents.

Our analysis focuses on the out-migration of young adults from these two cities, as young adulthood is the period of most intense migration activity. We generate a sample of young adults at risk of out-migration from the reproductive histories of the interviewed heads of household. These reproductive histories include information for all living children on the location of residence of non-coresident children and the date at which the children left the parents’ household. We restrict analysis to internal migration, defined as leaving the municipality of Santarém or Altamira (equivalent to crossing a county boundary in the U.S.).2 We consider the age range of 17–30 the at-risk period for migration in order to primarily capture labor migration among young adults. In the Brazilian Amazon, very few people pursue post-secondary school education, and data from the 2010 census indicate that only 4 % of individuals in Altamira and 5 % in Santarém had completed higher education (IBGE 2012). As such, we do not expect many individuals in our sample to migrate for educational purposes. We further limit the time at risk of migration to between 1980 and 2008 among individuals whose parents arrived in the survey city at least 1 year before a potential migration event. We thus exclude information from interviewed households with no living children aged 17–30 during the 1980–2008 time period. Individuals can contribute different numbers of years at risk, based on aging into the risk period at different times during the 1980–2008 period and based on censoring. Individuals were right-censored upon migrating, at 30 years of age, or in 2008. We chose to right censor the analysis in 2008 because surveys in Santarém were conducted in 2009, and thus we did not have a full year of data for that year.

Using this sample of individuals and years at risk, we built a person-year dataset of both migrants and non-migrants. The data contain both time-varying and time-invariant variables at the individual and household levels, with each observation representing a year in the life of an individual at risk of migration. The dataset contains 1,293 individuals (219 of whom migrated during the risk period), contributing a total of 10,832 person-years. We use these data to estimate a discrete-time hazard model of migration for each city. In addition, we estimate a binary logit model predicting the factors associated with remitting money to the parents’ household among our sample of 219 migrants. We examine how the propensity to remit varies between the two cities as well as by individual- and household-level characteristics.

This approach to creating a sample at risk of out-migration maximizes our ability to estimate the effects of sibling and parent networks. We have complete information on the migration histories of parents, allowing us to create measures of their places of birth and duration residing in the study city. We also have complete sibling sets with information on the date of out-migration for each sibling, allowing us to create a time-varying measure of extra-local sibling networks. For migrants and their siblings who moved outside of Pará, we are restricted to state-level data on their destinations. This prevents us from knowing whether an individual moved to the same city as sibling. As a result, we do not know whether having a sibling living in another location acts as a measure of extra-local social capital in the migrant network sense (the sibling provides information on employment and housing in that particular destination) or in a more general sense (the sibling provides basic information on how to successfully migrate and find employment, irrespective of location).

Another drawback is that we have left censoring, a common disadvantage in studies of migration. Of the young adults growing up in our study cities, we miss those whose parents have also left the city by the time of our surveys. We suggest that the most likely consequence of this left censoring is the underestimation of migration rates (assuming parents who left also have children who are more likely to have left) but not the systematic misestimation of the importance of networks. That is, we do not anticipate that the population of parents who have left contains an over- or underrepresentation of people for whom networks are important in the migration process. We cannot test these arguments, but we find that the value of being able to construct time-varying sibling networks and have linked parent and child information outweighs the potential sample selectivity bias in this analysis.

Descriptive statistics of the entire sample as well as destination choices of migrants are listed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. We use a number of variables as proxies for family networks, including whether or not an individual has a sibling living in another part of Brazil, the individual’s place of birth, the parents’ places of birth, and the length of time the parents have lived in the study city. The sibling location variable is time-varying and was constructed by determining the year that the first sibling within a household left for another location outside of the municipality in which the study city is located. An individual is coded as having at least one sibling living in another location during all of the person-years equal to or later than the year in which the first sibling left the municipality. Also included in the model is a set of dummy variables indicating the individual’s place of birth. Options include within the survey city, outside of the survey city but within the state of Pará, within the Northeast Region, and within all other regions of Brazil. Parents’ birthplaces are included as well, using the above location categories. An individual is coded with a number one if at least one of his or her parents was born in a given location. Lastly, a measure of location-specific capital is included in the model, represented by the year in which the parents first arrived in the survey city. For two-parent households, this value is calculated as the average of the years in which the mother and father arrived. In female-headed households, this value is the year in which the mother arrived, and in households with only a male head, this value is the year in which the father arrived. If the parent was born in the study city, then the year arrived is indicated by his or her birth year.3

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the study sample

| Time varying? | Altamira Mean |

Santarém Mean |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Family networks | |||

| Has a sibling living in another location | Yes | 0.41 | 0.48 |

| Birthplace | |||

| Survey city | No | 0.46 | 0.64 |

| Elsewhere in Pará | No | 0.24 | 0.27 |

| Northeast region | No | 0.17 | 0.07 |

| Elsewhere in Brazil | No | 0.12 | 0.03 |

| Parent birthplaces | |||

| At least one parent born in survey city | No | 0.12 | 0.25 |

| At least one parent born elsewhere in Pará | No | 0.34 | 0.52 |

| At least one parent born Northeast region | No | 0.57 | 0.27 |

| At least one parent born elsewhere in Brazil | No | 0.20 | 0.05 |

| Year parents arrived in city for first time | No | 1979 (11.25) | 1974 (13.83) |

| Human capital | |||

| Education (years) | |||

| 0–6 | No | 0.34 | 0.18 |

| 7–12 | No | 0.57 | 0.69 |

| >12 | No | 0.09 | 0.13 |

| Parents’ education | |||

| 4 Years or less | No | 0.68 | 0.42 |

| More than 4 years | No | 0.32 | 0.58 |

| Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics | |||

| Agea | Yes | 28.77 (8.34) | 28.90 (8.75) |

| Sex (1 = male) | No | 0.50 | 0.51 |

| Female-headed household | No | 0.34 | 0.35 |

| Number of siblings in family | No | 5.36 (2.77) | 5.38 (2.71) |

| Number of individuals | 567 | 726 | |

Standard deviations are shown in parentheses

Age in 2008 is displayed here

Table 2.

Migrant destinations

| Altamira Percentages |

Santarém | |

|---|---|---|

| North region | ||

| Within Pará | 50.00 | 37.23 |

| Amazonas | 3.66 | 41.61 |

| Other states | 17.07 | 8.76 |

| Northeast region | 3.66 | 3.65 |

| Southeast region | 14.63 | 5.11 |

| Central-west region | 8.54 | 1.46 |

| South region | 2.44 | 2.19 |

| Urban destination | 78.05 | 94.16 |

| Rural destination | 21.95 | 5.84 |

| Number of individuals | 82 | 137 |

Human capital variables include education and parents’ education. Demographic and socioeconomic variables include age, sex, whether the household is female-headed, and the number of siblings in the family. The variable measuring parental education was calculated by estimating the average years of schooling for the mother and father in two-parent households4 and then creating an indicator of whether that average was below or above primary school during the time period most respondents were children: 4 years or less or greater than 4 years. Lastly, given that the time period during which we examine migration spans 28 years, we control for temporal changes in migration by dividing the period into three decadal categories: the 1980s, the 1990s, and the 2000s.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the entire sample of young adult children of household heads from Altamira and Santarém, which includes 567 individuals from 191 households in Altamira and 744 individuals from 234 households in Santarém. Our family network variables show that a greater percentage of individuals in Santarém have siblings living outside of the study city than in Altamira. Individuals from Altamira, in contrast, have more networks to other places through their parents. Forty-six percent of individuals from Altamira had at least one parent born in the city or elsewhere in Pará, while 77 % had a parent born in the Northeast or elsewhere in Brazil. In Santarém, 77 % of individuals had a parent born in the city or elsewhere in Pará, while only 32 % had a parent born in another region of Brazil. In addition, the parents of individuals in Santarém arrived in the city an average 5 years earlier than in Altamira. Similarly, individuals in Altamira have more migration experience of their own; 46 % of them were born in the city, while 24 % were born in another part of Pará, 17 % were born in the Northeast, and 12 % were born in other regions of Brazil. In Santarém, a greater proportion of individuals were born in the city (64 %), while 27 % were born elsewhere in Pará, 7 % were born in the Northeast, and 3 % were born in other parts of Brazil. These data reflect the recent settlement history of the Altamira city and countryside. Individuals and their parents are more likely to have migrated into the city from other regions of Brazil, giving them more extra-local ties and stronger family networks elsewhere in the country.

We used educational attainment of the individual as well as that of his or her parents as proxies for human capital. The majority of individuals in both cities had between seven and 12 years of schooling (57 % in Altamira and 69 % in Santarém), while the educational attainment among parents is higher in Santarém than in Altamira. In Santarém, 58 % of parents have more than 4 years of education, while in Altamira only 32 % do so. The age of individuals in 2008 was roughly 29 years in both cities, and both samples were split evenly between males and females. Approximately, one-third of parental households in both cities were female headed, and there was an average of five siblings per family.

Migrant Destinations

Table 2 presents the destination locations of the 219 migrants in the sample (82 from Altamira and 137 from Santarém). Among migrants in Altamira, half remained within the state of Pará, 4 % migrated to the state of Amazonas, 17 % migrated to another state in the North region, and 29 % migrated to another region of Brazil. In Santarém, 37 % remained within Pará, 42 % migrated to Amazonas, 9 % migrated to another state in the North region, and 12 % migrated to another part of Brazil. These data indicate that although the two cities are located only a few hundred kilometers from one another, their migration flows are quite different. The difference between migration flows to the state of Amazonas is striking, as it serves as a destination for over 40 % of migrants from Santarém and only 4 % of migrants from Altamira. Santarém is located closer to Amazonas than Altamira, and Santarém is connected to Manaus (the capital of Amazonas and one of the largest cities in the Amazon) by the Amazon River, suggesting marginally lower transportation costs.

In addition, migrants from Altamira were more than twice as likely to make moves to distant locations within Brazil than were those from Santarém. Nearly, 30 % of migrants from Altamira moved to other states in Brazil instead of remaining in the North region, while only 12 % of migrants from Santarém did so. While we cannot directly observe the motivations of migrants, our results suggest that residents of Santarém are oriented to the Amazon region because of their deep roots in the region, while residents of Altamira are oriented to the rest of Brazil because of their recent family experiences of migration and strong network ties. In addition, while 94 % of migrants from Santarém went to urban destinations, only 78 % of those from Altamira did so. This suggests that individuals in Altamira are more likely to be seeking rural agricultural work or employment on megaprojects such as mines or dams, while those in Santarém are more likely to pursue urban employment opportunities, such as factory work.

Multivariate Results

Factors Associated with Out-Migration

Table 3 presents the results of a discrete-time event history model predicting the odds of out-migration from the two cities. Results indicate that sibling networks play an important role in fostering out-migration in Altamira. Individuals with a sibling living outside of the municipality are 2.6 times as likely to migrate in any given year as those whose siblings live within the municipality. In addition, an individual’s birthplace can be used as a proxy for family networks, as individuals who migrated to the study city after birth are likely to have stronger extra-local networks than those born within the city. In Altamira, we find that individuals born outside of the state of Pará are significantly more likely to migrate in a given year than those born in the city, and this relationship is particularly strong among those born in the Northeast region or other regions of Brazil. While the birthplaces of parents can also serve as a proxy for extra-local networks and the length of time the parents live in the city can serve as a proxy for location-specific capital, we do not find support for these theories in Altamira.

Table 3.

Event history model predicting the odds of migration, based on family networks and individual-and household-level characteristics

| Variable | Altamira

|

Santarém

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | Std. error | Odds ratio | Std. error | Significance of difference between coefficients | |

| Family networks | |||||

| Has a sibling living in another location birthplace (born in survey city is baseline) | 2.55*** | 0.62 | 0.97 | 0.21 | *** |

| Born elsewhere in Pará | 1.54 | 0.54 | 0.64* | 0.15 | * |

| Born in the Northeast region | 2.16* | 0.85 | 0.72 | 0.28 | |

| Born in another region | 2.17* | 0.95 | 0.87 | 0.45 | |

| Parent birthplaces | |||||

| At least one parent born in survey city | 1.32 | 0.76 | 0.82 | 0.22 | |

| At least one parent born elsewhere in Pará | 0.50 | 0.23 | 2.07*** | 0.50 | *** |

| At least one parent born Northeast region | 0.70 | 0.35 | 1.77** | 0.48 | * |

| At least one parent born elsewhere in Brazil | 1.06 | 0.56 | 2.32** | 0.89 | |

| Year parents arrived in city for first time | 0.99 | 0.01 | 1.02** | 0.01 | |

| Human capital | |||||

| Education (0–6 years is baseline) (years) | |||||

| 7–12 | 1.30 | 0.36 | 1.08 | 0.26 | |

| >12 | 1.47 | 0.59 | 1.51 | 0.47 | |

| Parents’ education (4 years or less is baseline) | |||||

| More than 4 years | 1.71* | 0.51 | 0.65** | 0.13 | ** |

| Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics | |||||

| Age | 0.94* | 0.03 | 0.98 | 0.02 | |

| Sex (1 = male) | 1.61** | 0.38 | 0.92 | 0.17 | * |

| Female-headed household | 1.09 | 0.27 | 1.53** | 0.33 | |

| Number of siblings in family | 1.03 | 0.05 | 1.07* | 0.04 | |

| Time period: (1980s is baseline) | |||||

| 1990s | 0.53** | 0.17 | 0.55** | 0.13 | |

| 2000s | 0.51* | 0.20 | 0.42*** | 0.12 | |

| Number of person-years | 4,874 | 5,958 | |||

| Likelihood ratio Chi square | 53.35*** | 47.65*** | |||

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.06 | 0.04 | |||

p < 0.1;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01

In Santarém, we find evidence of a very different relationship between family networks and migration. Individuals with siblings living outside of the municipality are no more likely to migrate than those without, while individuals born within Santarém are more likely to migrate than those born elsewhere. In contrast, we find that individuals with at least one parent born outside of the study city—whether in another part of Pará, the Northeast region, or other parts of Brazil—are significantly more likely to migrate than those without. Additionally, we find support for DeVanzo’s theory regarding location-specific capital. Individuals whose parents arrived in Santarém more recently are more likely to migrate in a given year than those whose parents have lived in the city longer. These results indicate that individuals whose parents have more extra-local networks (as proxied by them being born outside of Santarém) and less location-specific capital within Santarém (as proxied by their families having moved to the city more recently) are more likely to migrate. Yet, one’s own extra-local experience and sibling networks do not play a role in fostering out-migration.

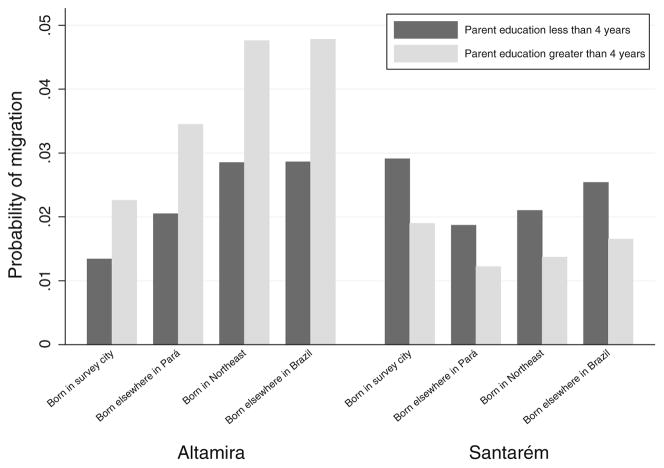

We then examine the relationship between human capital and migration using an individual’s educational attainment as well as that of his or her parents. While an individual’s educational attainment is not associated with the risk of migration, parental education plays an important role. In Altamira, an individual whose parents have more than 4 years of education is 1.7 times as likely to migrate in any given year as one whose parents have four or less years of education, while in Santarém, an individual whose parents have higher educational attainment is 35 % less likely to migrate. In urban areas, parental educational attainment is associated with the household’s earning potential; therefore, these findings indicate that in Santarém, individuals from households with a lower earning potential may be migrating to supplement household income, while in Altamira individuals from families with greater earning potential are actually more likely to migrate.

Figure 2 shows the combined impact of these factors across the two cities. It presents the predicted probabilities of migration in a given year by city, birthplace, and parental education. In Altamira, the probability of migration is the lowest among those born in the city, increases among those born elsewhere in Pará, and is the highest among those born in the Northeast and other regions of Brazil. In addition, among all four birthplace groups, having parents with four or more years of education is associated with a higher risk of migration. In contrast, individuals born in Santarém have the highest likelihood of migration, followed by those born elsewhere in Brazil, those born in the Northeast region, and those born elsewhere in Pará. Further, those whose parents have less than 4 years of education are more likely to migrate. The predicated probabilities lend further support to the findings that in Altamira, an individual’s extra-local social capital (as proxied by being born outside the study city) as well as his or her family’s human capital and earning potential (as proxied by parental education) are both positively associated with the risk of migration. In contrast, individuals in Santarém are less likely to migrate if they were born outside of the study city and if their parents have higher levels of education. This indicates that in Santarém, low household earning potential is a more important driver of migration than an individual’s extra-local social capital.

Fig. 2.

Predicted probabilities of migration in a given year for the study cities, by birthplace and parental education. Note Probabilities are calculated for males, mean age, 7–12 years of education, parents born elsewhere in Pará, mean year parents arrived, have sibling(s) living in other locations, non-female-headed household, mean number of siblings in the family, and during the 1990’s

We then examine the relationship between demographic and socioeconomic characteristics and migration, focusing on an individual’s age and sex as well as the number of siblings in the family and whether the household is female headed. In Altamira, we find that males are 1.6 times as likely as females to migrate and that the likelihood of migration decreases with age. In Santarém, while age and sex are not linked to migration risk, we find that individuals from female-headed households are 1.5 times as likely to migrate in a given year as those from two-parent or male-headed households. Further, each additional sibling in the family increases an individual’s likelihood of migration by 7 %. These variables both serve as proxies for household need, as female-headed households in Brazil and Latin America as a whole have been found to have a lower earning potential and a greater risk of living in poverty (Barros et al. 1997; de la Rocha and Gantt 1995). In addition, having more children often correlates with poverty due to larger expenditures for food, school supplies, clothing, etc. (Musgrove 1980; Rose and Charlton 2002).

Lastly, the right-hand column of Table 2 shows the significance of the difference between Altamira and Santarém on each independent variable. We find significant differences between the cities in the role of extra-local sibling networks, whether an individual was born in Pará, whether an individual has a parent born elsewhere in Pará or in the Northeast region, parents’ level of education, and sex.

Factors Associated with Remitting

Lastly, we examine whether the propensity for migrants to remit money to their parents’ households differs between the two cities as well as by individual- and household-level characteristics. Table 4 presents the results of a binary logit model predicting remittances. Net of other factors, we find that migrants from Santarém are 5.6 times as likely to remit money as those from Altamira. In addition, we find that migrants with a parent born in Pará are significantly less likely to remit and that older migrants are more likely to remit than younger migrants. Finally, we find that migrants from a female-headed household are 3.7 times as likely to remit than those from two-parent or male-headed households. These results suggest that migration from Santarém is more likely to be a household-level income generation strategy, that migration from Altamira is more likely to be an individual-level strategy, and that migrants from female-headed households (who face higher rates of poverty) are more likely to send money home.

Table 4.

Binary logit model predicting whether a migrant remits money to his/her parents’ household

| Variable | Odds ratio | Std. error |

|---|---|---|

| City (1 = Santarém) | 5.56*** | 2.90 |

| Family networks | ||

| Has a sibling living in another location birthplace (born in survey city is baseline) | 0.63 | 0.28 |

| Born elsewhere in Pará | 0.92 | 0.50 |

| Born in the Northeast region | 0.56 | 0.40 |

| Born in another region | 2.11 | 1.47 |

| Parent birthplaces | ||

| At least one parent born in survey city | 0.51 | 0.45 |

| At least one parent born elsewhere in Pará | 0.36* | 0.21 |

| At least one parent born Northeast region | 2.30 | 1.34 |

| At least one parent born elsewhere in Brazil | 2.08 | 1.66 |

| Year parents arrived in city for first time | 1.00 | 0.02 |

| Human capital | ||

| Education (0–6 years is baseline) (years) | ||

| 7–12 | 1.05 | 0.56 |

| >12 | 0.71 | 0.52 |

| Parents’ education (4 years or less is baseline) | ||

| More than 4 years | 0.56 | 0.27 |

| Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics | ||

| Age | 1.10* | 0.06 |

| Sex (1 = male) | 1.08 | 0.44 |

| Female-headed household | 3.72*** | 1.75 |

| Number of siblings in family | 0.95 | 0.08 |

| Number of individuals | 219 | |

| Likelihood ratio Chi square | 44.15*** | |

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.19 | |

Conclusions

In this paper, we set out to estimate the roles of social and human capital in migrant decision-making as well as how these factors varied between two medium-sized Amazon cities—Santarém and Altamira—located within the state of Pará. Consistent with prior literature, we see evidence that social connections and higher levels of human capital facilitate migration among young adults. The relative importance of these two factors, however, varies across social context even in these two nearby cities. Santarém is a larger city than Altamira, has an older settlement history, and has higher levels of poverty and inequality. In addition, individuals in Altamira as well as their parents are more likely to have been born in distant regions of Brazil, while those in Santarém are more likely to have been born within the city or elsewhere in the state of Pará. Our results indicate that these factors have shaped migration flows and drivers very differently between the two cities.

In Altamira, we find that extra-local social capital, rather than human capital or socioeconomic deprivation, is the primary driver of migration among youth and young adults. Extra-local networks—the ties that link a potential migrant to friends and family in other parts of Brazil—play an important role in determining migration in this context. In Santarém, the picture is quite different. Socioeconomic deprivation is an important driver of migration, while family networks play a more minor role, with the extra-local ties of parents fostering migration and location-specific capital hindering it. These results indicate that extra-local networks function differently between Altamira and Santarém, lending support to both Garip (2008) and Davis and colleagues’ (2002) work on the importance of disaggregating networks due to the roles that different types of networks play in transferring information and resources to potential migrants. In the Thai context of rural–urban migration, Garip argues that the migration experience of parents tends to provide information about more traditional employment opportunities (e.g., farm or construction work), while peer networks provide information on higher paying factory or service jobs. Our results suggest that in Altamira, migrants are utilizing their own ties as well as those of their siblings, which supports Garip’s concept of peer networks providing information about more desirable, higher paying jobs. In contrast, in Santarém, migrants are utilizing their parents’ networks in order to find jobs that will assist with generating additional household income.

These results also support Browder and Godfrey’s (1997) argument that migration in the Brazilian Amazon is a complex, heterogeneous process. Examining urban out-migration at the sub-regional scale allows us to account for this heterogeneity, and we find that the relative roles of migrant networks versus economic deprivation function quite differently between these two geographically proximate but historically and socioeconomically distinct Amazonian cities. In Altamira, migration is by and large an individual-level opportunistic investment strategy. Young adults with greater amounts of extra-local social capital are able to capitalize on networks elsewhere in Brazil and are, therefore, more likely to migrate to pursue education or better employment options. In Santarém, our results indicate that migration is generally a function of necessity. Young adults from poorer, more economically marginalized households, migrate in search of better income generation opportunities in light of Santarém’s limited employment market. Migrants tend to move to the adjacent state of Amazonas, presumably to work in Manaus (one of the Amazon’s largest cities) rather than to more distant locations within Brazil. Making closer moves is less costly and risky, particularly in the absence of family networks in the destination area.

Our findings provide strong support for the impact of a number of individual- and household-level characteristics on migration, but we were not able to directly estimate the impacts of characteristics of the communities, such as date of settlement and industrial organization. Based on our results shown here and our knowledge of the cases, we argue that the city context matters in the following ways. First, as we note in describing the cities, Altamira is a more economically vibrant city, with less of a history of boom and bust development and with better current economic performance. Thus, we might expect that in Brazil, a middle-income country experiencing economic growth, migration patterns in small cities will reflect individual motivations to invest in human capital or increase future earnings through migration. Second, we might alternatively argue that the differences between the two cities reflect cultural differences due in part to their recent histories. Altamira is a recent frontier, with an ethos of hard work being rewarded and a history of risk-taking. In contrast, Santarém has suffered more from the vagaries of national and global price and demand volatility, as well as from a more precarious biophysical environment for agriculture and ranching. The higher levels of uncertainty in returns to labor and other investments could have created an orientation toward meeting basic needs through migration in contrast to using migration as an investment.

On a broader scale, this study offers insights into the varying ways that urban out-migration functions in cities at different stages of economic development. In the case of a middle-income country such as Brazil, urban out-migration ranges from a household-level strategy driven by poverty and deprivation to an opportunistic individual-level strategy driven by social capital. With increasing development, economic growth, and levels of mobility around the country, we expect a transition toward the latter in most cities. This suggests that population redistribution will increasingly follow regional economic development as people respond to employment opportunities rather than flee from poverty.

Footnotes

We used the size of the tracts (as well as tract boundaries) from the 2007 population count. This count is an intercensal count of population that applies a short-form survey to all households to describe the population of the country and its administrative units on size and a limited set of characteristics (IBGE 2007).

Only two international migrants were observed in our sample. These were excluded from the analysis.

We estimated alternative models using the earliest year in which any parent arrived and using the latest year in which any parent arrived. Substantive results did not change.

We estimated alternative models using the highest education completed by either parent and using the lowest education completed by either parent. Substantive results did not change.

References

- Alonso S, Castro E. Small and medium size cities. Lima: Instituto del Bien Comun; 2005. The process of transformation of rural areas into urban areas in Altamira and its representation. [Google Scholar]

- Amorim ATdS. Santarém: uma síntese histórica [Santarém: a historical synthesis] Canoas, RS: Editoria da ULBRA; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Arruda HPd. Colonização official e particular. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Nacional de Colonização e Reforma Agrária; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri AF, Carr DL, Bilsborrow RE. Migration within the frontier: The second generation colonization in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Population Research and Policy Review. 2009;28(3):291–320. doi: 10.1007/s11113-008-9100-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros R, Fox L, Mendonca R. Female-headed households, poverty, and the welfare of children in urban Brazil. Economic Development and Cultural Change. 1997;45(2):231–257. [Google Scholar]

- Browder JO, Godfrey BJ. Frontier urbanization in the Brazilian Amazon: A theoretical framework for urban transition. Yearbook. Conference of Latin Americanist Geographers. 1990:56–66. [Google Scholar]

- Browder JO, Godfrey BJ. Rainforest cities: Urbanization, development, and globalization of the Brazilian Amazon. New York: Columbia University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Cerrutti M, Massey DS. On the auspices of female migration from Mexico to the United States. Demography. 2001;38(2):187–200. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen B. Urbanization in developing countries: Current trends, future projections, and key challenges for sustainability. Technology in Society. 2006;28(1–2):63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Comissão Executiva do Plano da Lavoura Cacaueira (CEPLAC) [Accessed January 21, 2013];O Estado do Pará e a produção Brasileira de cacau. 2009 http://www.ceplacpa.gov.br/site/?p=3009.

- Confederação Nacional de Municípios. [Accessed May 9, 2011];Histórico Altamira, Pará. 2011 http://www.altamira.pa.cnm.org.br/portal1/municipio/historia.asp?iIdMun=100115009.

- Costa SMF, Brondizio E. Inter-urban dependency among Amazonian cities: Urban growth, infrastructure deficiencies, and socio-demographic networks. Redes. 2009;14(3):211–234. [Google Scholar]

- DaVanzo J. Repeat migration, information costs, and location-specific capital. Population and Environment. 1981;4(1):45–73. [Google Scholar]

- Davis B, Stecklov G, Winters P. Domestic and international migration from rural Mexico: Disaggregating the effects of network structure and composition. Population Studies. 2002;56(3):291–309. [Google Scholar]

- de la Rocha MG, Gantt BB. The urban family and poverty in Latin America. Latin American Perspectives. 1995;22(2):12–31. [Google Scholar]

- de Sá MER, da Costa SMG, de Oliveira Tavares LP. O rural-urbano em Santarém: Interfaces e territórios produtivos. In: Cardoso Ana Claudia Duarte., editor. O rural e o urbano na Amazônia: Diferentes olhares em perspectivas. Belém: EDUFPA; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Deléchat C. International migration dynamics: The role of experience and social networks. Labour. 2001;15(3):457–486. [Google Scholar]

- Fearnside PM. Brazil’s Amazon settlement schemes: Conflicting objectives and human carrying capacity. Habitat International. 1984;8(1):45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Fussell E, Massey DS. The limits to cumulative causation: International migration from Mexican urban areas. Demography. 2004;41(1):151–171. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garip F. Social capital and migration: How do similar resources lead to divergent outcomes? Demography. 2008;45(3):591–617. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandin G. Fordlandia: The rise and fall of Henry Ford’s forgotten jungle city. New York: Macmillan; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera JA, Moreira RP. Restistência e confltos sociais na Amazônia Paraense: A luta contra o empreendimento Hidrelétrico de Belo Monte. Campo-Território. 2013;8:130–151. [Google Scholar]

- Hoddinott J. A model of migration and remittances applied to Western Kenya. Oxford Economic Papers. 1994;46(3):459–476. [Google Scholar]

- IBGE. Contagem população 2007. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- IBGE. [Accessed May 9, 2011];Cidades—Para. 2011 http://ibge.gov.br/cidadesat/topwindow.htm?1.

- IBGE. Brazil demographic census 2010. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE); 2012. [Google Scholar]

- IBGE. [Accessed April 9, 2014];Estados—Pará. 2014 http://www.ibge.gov.br/estadosat/perfil.php?sigla=pa.

- Kanaiaupuni SM. Reframing the migration question: An analysis of men, women, and gender in Mexico. Social Forces. 2000;78(4):1311–1347. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS. Understanding Mexican migration to the United States. American Journal of Sociology. 1987;92(6):1372–1403. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS. Social structure, household strategies, and the cumulative causation of migration. Population Index. 1990;56(1):3–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Arango J, Hugo G, Kouaouci A, Pellegrino A, Taylor JE. Theories of international migration: A review and appraisal. Population and Development Review. 1993;19(3):431–466. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Aysa M. Social capital and international migration from Latin America. Paper presented at Expert Group Meeting on International Migration and Development in Latin America and the Caribbean; Mexico City. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, García España F. The social process of international migration. Science. 1987;237(4816):733–738. doi: 10.1126/science.237.4816.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie D, Rapoport H. Network effects and the dynamics of migration and inequality: Theory and evidence from Mexico. Journal of Development Economics. 2007;84(1):1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Moran E. Developing the Amazon. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Musgrove P. Household size and composition, employment, and poverty in urban Latin America. Economic Development and Cultural Change. 1980;28(2):249–266. [Google Scholar]

- Osili UO. Remittances and savings from international migration: Theory and evidence using a matched sample. Journal of Development Economics. 2007;83(2):446–465. [Google Scholar]

- Palloni A, Massey D, Ceballos M, Espinosa K, Spittel M. Social capital and international migration: A test using information on family networks. American Journal of Sociology. 2001;106(5):1262–1298. [Google Scholar]

- Perz SG. Population growth and net migration in the Brazilian Legal Amazon, 1970–1996. In: Wood CH, Porro R, editors. Deforestation and land use in the Amazon. Gainesville: University Press of Florida; 2002. pp. 107–129. [Google Scholar]

- Perz SG, Leite F, Simmons C, Walker R, Aldrich S, Caldas M. Intraregional migration, direct action land reform, and new land settlements in the Brazilian Amazon. Bulletin of Latin American Research. 2010;29(4):459–476. [Google Scholar]

- Prefeitura de Santarém. [Accessed July 26, 2012];Histórico do município. 2012 http://www.santarem.pa.gov.br/conteudo/?item=121&fa=60.

- Prefeitura de Santarém. [Accessed January 21, 2013];Ciclos econômicos. 2013 http://www.santarem.pa.gov.br/conteudo/?item=114&fa=61.

- Reed HE, Andrzejewski CS, White MJ. Men’s and women’s migration in coastal Ghana: An event history analysis. Demographic Research. 2010;22(25):771–812. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2010.22.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose N. A persisting misconception about the drought of 1958 in northeast Brazil. Climatic Change. 1980;2(3):299–301. [Google Scholar]

- Rose D, Charlton KE. Prevalence of household food poverty in South Africa: Results from a large, nationally representative survey. Public Health Nutrition. 2002;5(03):383–389. doi: 10.1079/phn2001320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JA. Fordlandia and Belterra, rubber plantations on the Tapajos River. Economic Geography. 1942;18:125–145. [Google Scholar]

- Sana M, Massey DS. Household composition, family migration, and community context: Migrant remittances in four countries. Social Science Quarterly. 2005;86(2):509–528. [Google Scholar]

- Shefer D, Steinvortz L. Rural-to-urban and urban-to-urban migration patterns in Colombia. Habitat International. 1993;17(1):133–150. doi: 10.1016/0197-3975(93)90050-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjaastad LA. The costs and returns of human migration. The Journal of Political Economy. 1962;70(5):80–93. [Google Scholar]

- Stark O, Bloom DE. The new economics of labour migration. American Economic Review. 1985;75(1):191–196. [Google Scholar]

- Stark O, Lucas REB. Migration, remittances, and the family. Economic Development and Cultural Change. 1988;36(3):465–481. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor EJ. The new economics of labour migration and the role of remittances in the migration process. International Migration. 1999;37(1):63–88. doi: 10.1111/1468-2435.00066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JE, Martin PL. Human capital: Migration and rural population change. Handbook of Agricultural Economics. 2001;1(A):457–511. [Google Scholar]

- Todaro MP. A model of labor migration and urban unemployment in less developed countries. The American Economic Review. 1969;59(1):138–148. [Google Scholar]

- Umbuzeiro A, Umbuzeiro U. Altamira e sua História. Belém: Ponto Press Ltda; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- VanWey LK. Altruistic and contractual remittances between male and female migrants and households in rural Thailand. Demography. 2004;41(4):739–756. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanWey LK, D’Antona AO, Brondizio ES. Household demographic change and land use/land cover change in the Brazilian Amazon. Population and Environment. 2007;28(3):163–185. [Google Scholar]

- VanWey LK, Vithayathil T. Off-farm work among rural households: A case study in the Brazilian Amazon. Rural Sociology. 2012;78(1):29–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-0831.2012.00094.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White M, Lindstrom D. Internal migration. In: Poston DL, Micklin M, editors. Handbook of population. New York: Springer; 2005. pp. 311–346. [Google Scholar]

- WinklerPrins AMGA. House-lot gardens in Santarém, Pará, Brazil: Linking rural with urban. Urban Ecosystems. 2002;6(1):43–65. [Google Scholar]

- Winters P, De Janvry A, Sadoulet E. Family and community networks in Mexico-U.S. migration. Journal of Human Resources. 2001;36(1):159–184. [Google Scholar]

- Xavier TMBS, Xavier AFS. Classificação de anos secos e chuvosos na Região Nordeste do Brasil e sua distribuição espacial. III Congresso Brasileiro de Meteorologia; Belo Horizonte. 1984. pp. 267–275. [Google Scholar]

- Yoder ML, Fuguitt G. Urbanization, frontier growth, and population redistribution in Brazil. Luso-Brazilian Review. 1979;16(1):67–90. [Google Scholar]