Abstract

The aim of the present work is to analyze all scientific evidence to verify whether similarities supporting a unified explanation for odontomas and supernumerary teeth exist. A literature search was first conducted for epidemiologic studies indexed by PubMed, to verify their worldwide incidence. The analysis of the literature data shows some interesting similarities between odontomas and supernumerary teeth concerning their topographic distribution and pathologic manifestations. There is also some indication of common genetic and immuno-histochemical factors. Although from a nosological point of view, odontomas and supernumeraries are classified as distinct entities, they seem to be the expression of the same pathologic process, either malformative or hamartomatous.

Keywords: Supernumerary teeth, Odontomas, Odontogenic tumors, Tooth retention.

Introduction

Odontomas (ODs) are currently still classified by the World Health Organization1, 2among the benign mixed odontogenic tumors as lesions in which all odontogenic tissues (enamel, cement and dentin) are involved in varying proportions and different degrees of development, although they are really considered as hamartomas or malformations.2

They are typically divided into compound and complex ODs although mixed forms have been described. Compound ODs (CpODs) are formed by many little tooth-like structures often strictly adapted to each other and held together by a more or less complete connective capsule. CpODs are easily recognizable; they are usually small but large lesions contain up to 100 denticles.3Complex ODs (CxODs) are formed by a single amorphous mass of mature odontogenic tissues without any structural organization, with tissues arranged in a more or less disorderly pattern.4The degree of morpho-differentiation varies from lesion to lesion. In some cases the calcified matrix is predominant, in others there are islands of pulp tissue in association with cords and buds.4

Supernumerary teeth or supernumeraries (SPNs) are teeth present in addition to the normal tooth set, both in the permanent and the primary dentitions. They may be single or multiple, unilateral or bilateral, erupted or un-erupted and may occur in the upper or/and the lower jaws. They are morphologically classified as supplemental if their crown resembles that of normal teeth, conoid if it is conical, tuberculate if the occlusal crown surface presents several cusps, infundiboliform or invaginated if the crown presents a deep central groove starting from the occlusal surface, and odontome-like or mis-shaped if they cannot be included in any other morphological type. SPNs represent a common occurrence in the oral cavity and can lead to aesthetic and functional alterations.

Etiology

Odontomas

The exact etiology of ODs is poorly known. They may arise from tooth germs or teeth still in the growth process induced by local trauma, infection, inheritance, and genetic mutations.

Supernumerary teeth

The etio-pathogenesis of SPNs is still controversial although several theories have been proposed over time.5, 6One theory suggests that the SPN is the result of a dichotomy of the tooth bud. The “hyperactivity theory”, which is well-supported by the literature, suggests that SPNs develop as a result of local hyperactivity of the dental lamina. Heredity may play a role in the occurrence of this anomaly since SPNs are more common in relatives of affected children than in the general population.7 An abnormal reaction to local traumatic episodes and environmental factors are also to be considered as possible etiological factors.

A common origin for ODs and SPNs could be hypothesized on the basis of the following two considerations. Firstly, although ODs are nowadays classified as tumours, they usually stop increasing in volume when they are completely mineralized and this clinical behaviour is different from all other tumours of the body, while it is typical of non-tumoral lesions such as dysplastic, hamartomatous and malformative conditions, among which SPNs. Secondly, it is common to find single SPNs that are usually defined as odontoma-like teeth because of their irregular morphology.

The aim of the present review is to analyze all scientific evidence to verify if there are similarities that can support a common explanation for ODs ad SPNs.

Materials and Methods

A literature search was conducted for epidemiologic studies involving ODs and SPNs that are indexed by PubMed from 1967 to 2012 to verify their worldwide incidence. The article selection was initially performed according to geographic and temporal distribution criteria. Afterwards, from the references of the selected articles, some other relevant articles were chosen. Thus, in total 42 articles were selected for ODs from 1976 to 20118-49and 19 for SPNs from 1967 to 201250-68taking into account age and gender of patients, morphologic type, topography and clinical relevance of both pathologies.

Results

Epidemiology

Odontomas

Four thousand and one ODs were evaluated (Table 1). The incidence of ODs was reported ranging from 0.24%14, 20to 1.21%.12, 45The overall incidence of the present aggregated sample was 0.64% (2774 cases) among 431,545 histological maxillo-facial samples (Table 2) and 30.4% among all the diagnosed odontogenic tumours (2731/8984 cases; Table 3).

Table 1.

Complex (Cx) and Compound (Cp) Odontomas (ODs) by patient genderand age at diagnosis.

| Authors | Total n. of ODs for gender/age | CxODs - CpODs n. |

CxODs:CpODs ratio |

Total male (CxODs) (CpODs) |

Total female (CxODs) (CpODs) |

M:F ratio (CxODs) (CpODs) |

CxOD average age (range) | CpOD average age (range) | Total OD average age (range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SolukTekkesin et al. 2011, Turkey(8) | 160/160 | 99 -57 (4 mixed) |

1:0.57 | 80 | 80 | 1:1 | 27.9 (3-81) |

||

| Osterne et al. 2011, Brazil(9) |

36 /36 | 12 | 24 | 0.5:1 | 28.1±20.3 (4-78) |

||||

| Saghravanian et al. 2010, Iran(10) | 44/44 | 27 - 17 | 1:0.63 | 18 | 26 | 0.7:1 | 21.4 | ||

| Tawfik and Zyada 2010, Egypt(11) |

11/11 | 4 - 7 | 0.57:1 | 3 (1) (2) |

8 (3) (5) |

0.37:1 (0.4:1) (0.34:1) |

38±25.17 | 15.29±7.72 | 23.55 (4-80) |

| El-Gehani et al. 2009, Libya(12) |

29/29 | 10 - 19 | 0.52:1 | 10 (5) (5) |

19 (5) (14) |

0.52:1 (1:1) (0.36:1) | |||

| da Silva et al. 2009, Portugal(13) |

48/48 | 14 / 34 | 0.41:1 | 26 | 22 | 1:0.85 | 29.35±16.1 | 22.7±13.67 | 26±15.2 (8-64) |

| Luo and Li 2009, China(14) |

80/80 | 47 / 33 | 1:0.7 | 42 (29) (13) |

38 (18) (20) |

1:0.9 (1:0.62) (0.65:1) |

24.62±16.54 (5-77) | 16.48±8.16 (3-37) | |

| Avelar et al. 2008, Brazil(15) |

54/54 | 17 | 37 | 0.46:1 | 27 (4-84) |

||||

| Jing et al. 2007, China(16) |

78/78 | 58 / 20 | 1:0.34 | 38 (31) (7) |

40 (27) (13) |

0,95:1 (1:0.87) (0.54:1) | 28.2±16.8 | 18.8±11.5 | 25.8 |

| Pippi 2006, Italy(17) |

27/28 | 13 / 15 | 0.87:1 | 17 (8) (9) |

10 (4)(6) | 1:0.6 (1:0.5) (1:0.67) |

20.5 | ||

| Buchner et al. 2006, USA(18) |

762 | 18.4 (1-90) |

|||||||

| Olgac et al. 2006, Turkey(19) |

109 | 67 / 42 | 1:0.63 | 59 (32) (27) |

50 (35) (15) |

1:0.85 (0.9:1) (1:0.56) | |||

| Ladeinde et al. 2005, Nigeria(20) |

8/8 | 4 | 4 | 1:1 | 22.3±11.2 (10-45) |

||||

| Adebayo et al. 2005, Nigeria(21) |

7 | 4 | 3 | 1:0.75 | |||||

| Tomizawa et al. 2005, Japan(22) |

39 | 7 / 30 | 0.23:1 | 23 | 15 | 1:0.65 | |||

| Fernandes et al. 2005, Brazil(23) |

85/85 | 52 / 33 | 1:0.63 | 47 (28) (19) |

38 (24) (14) |

1:0.8 (1:0,86) (1:0.74) |

22.2±14.7 | 20.5±12.3 | |

| Tamme et al. 2004, Estonia(24) |

26/26 | 14 / 12 | 1:0.86 | 8 (5) (3) |

18 (9) (9) |

0.44:1 (0.55:1) (0.33:1) | 25.4 | 21.8 | 23.7 |

| Amado-Cuesta et al. 2003, Spain(25) | 61/61 | 23 /38 | 0,6:1 | 32 | 29 | 1:0.9 | 29.3 (14-46) |

19.1 (6-42) |

23.7 (6-46) |

| Hisatomi et al. 2002, Japan(26) |

106/106 | 41 / 62 | 0.66:1 | 55 (21) (33) |

51 (20) (29) |

1:0.93 (1:0.95) (1:0.88) | 23 | 19.9 | 20.9 (3-70) |

| Ochsenius et al. 2002, Chile(27) |

162/162 | 92 / 71 | 1:0.77 | 77 (42) (35) |

85 (49) (36) |

0,9:1 (0.86:1) (0.97:1) |

20.8±13.5 | 17±10.7 | |

| Miki et al. 1999, Japan(28) |

47/47 | 22 / 25 | 0.8:1 | 27 | 20 | 1:0.74 | 20.8 | 23.5 | 22±9 (8-48) |

| Lu et al. 1998, China(29) |

51/51 | 37 / 14 | 1:0.38 | 23 (20) (3) |

28 (17) (11) |

0,82:1 (1:0.85) (0.27:1) | 27.7 | 17 | |

| Philipsen et al. 1997, Denmark(4) |

134 | 56 / 78 | 0.72:1 | 59 (23) (36) |

75 (33) (42) |

0.79:1 (0.7:1) (0.86:1) |

18.89 (3-74) |

18.55 (1-67) |

18.69 (1-74) |

| Mosqueda-Taylor et al. 1997, Mexico(30) | 120 | 63 / 49 | 1:0.7 | 59 | 61 | 0.96:1 | |||

| Macdonald-Jankowski 1996, China(31) |

39/39 | 21 / 18 | 1:0.86 | 18 (8) (10) |

21 (13) (8) |

0.86:1 (0.61:1) (1:0.8) | 24.6±12.4 | 20.9±8.9 | 22.9±10.9 (0-59) |

| Odukoya 1995, Nigeria(32) |

12/12 | 5 | 7 | 0.7:1 | 20.7±11.7 (10-54) |

||||

| Daley et al. 1994, Canada(33) |

202 | 74 / 128 | 0.58:1 | ||||||

| Gunhan et al. 1990, Turkey(34) |

74/74 | 44 | 30 | 1:0.68 | 20.6 (9-60) |

||||

| Kaugars et al. 1989, USA(35) |

351 | 170 | 181 | 0.94:1 | |||||

| O'Grady et al.1987, Australia(36) | 118/118 | 76 / 36 | 1:0.47 | 52 | 62 | 0.84:1 | 17.6 (2-60) |

||

| Or and Yücetas 1987, Turkey(37) |

49/49 | 20 / 29 | 0.69:1 | 28 (12) (16) |

21 (8) (13) |

1:0.75 (1:0.67) (1:0.81) | 22.9 | 23.8 | |

| Pizzirani and Gemesio 1984, Italy(38) | 17 | 7 | 10 | 0.7:1 | |||||

| Toretti et al. 1984, UK(39) | 167 | 75 / 92 | 0.8:1 | 83 | 84 | 0.99:1 | |||

| Bodin et al. 1983, Sweden(40) | 65 | 21 / 44 | 0.45:1 | 38 | 27 | 1:0.71 | |||

| Slootweg 1981, The Netherlands(41) | 121/126 | 78 / 48 | 1:0.6 | 78 | 43 | 1:0.55 | 20.3 | 14.8 | |

| Morning 1980, Denmark(42) | 31 | 16 | 15 | 1:0.94 | |||||

| Regezi et al. 1978, USA(43) |

473 | 214 / 259 | 0.82:1 | 19 (2-79) |

|||||

| Budnick 1976, USA(44) | 135/149 | 76 / 73 | 1:0.96 | 79 | 56 | 1:0.7 | 14.8 |

Table 2.

Odontomas from histological samples.

| Authors | Sample | n. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| SolukTekkesin et al. 2011, Turkey(8) | 40999 | 160 (0.39) |

| Osterne et al. 2011, Brazil(9) | 6231 | 36 (0.58) |

| Saghravanian et al. 2010, Iran(10) | 8766 | 44 (0.50) |

| El-Gehani et al. 2009, Libya(12) | 2390 | 29 (1.21) |

| Luo and Li 2009, China(14) | 33354 | 80 (0.24) |

| Buchner et al. 2006, USA(18) | 91178 | 826 (0.90) |

| Ladeindeet al. 2005, Nigeria(20) | 3337 | 8 (0.24) |

| Adebayo 2005, Nigeria(21) | 990 | 7 (0.70) |

| Fernandes et al. 2005, Brazil(23) | 19123 | 85 (0.44) |

| Tamme et al. 2004, Estonia(24) | 10141 | 26 (0.25) |

| Ochsenius et al. 2002, Chile(27) | 28041 | 162 (0.58) |

| Santos et al. 2001, Brazil(45) | 5289 | 64 (1.21) |

| Mosqueda-Taylor et al. 1997, Mexico(30) | 16079 | 121 (0.75) |

| Odukoya 1995 Nigeria(32) | 1511 | 12 (0.79) |

| Daley et al. 1994, Canada(33) | 40000 | 202 (0.50) |

| Kaugars et al. 1989, USA(35) | 53824 | 351 (0.65) |

| Happonen et al. 1982, Finland(46) | 15758 | 88 (0.569) |

| Regezi et al. 1978, USA(43) | 54534 | 473 (0.83) |

Table 3.

Complex (Cx) and Compound (Cp) Odontomas (ODs) among Odontogenic Tumors (OTs). Data according to the 1992 WHO Classification.

| Authors | OTs | ODs n. (%) | Cx - CpODs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Osterne et al. 2011, Brazil(9) |

133 →185 |

36 27.07 →19.46 |

|

| Saghravanian et al. 2010, Iran(10) | 165 | 44 (26.7) | 27 - 17 |

| TawfikandZyada 2010, Egypt(11) |

66 →82 |

11(16.7 →13.4) |

4 - 7 |

| El-Gehani et al. 2009, Libya(12) | 96 | 29 (30.2) | 10 - 19 |

| da Silva et al. 2009, Portugal(13) | 65 | 48 (73.9) | 14 - 34 |

| Luo and Li 2009, China(14) | 802 | 80 (9.98) | 47 -33 |

| Avelar et al. 2008, Brazil(15) | 171 | 54 (31.6) | |

| Jing et al. 2007, China(16) | 1054 →1642 |

78 (7.4) →4.7 |

58 - 20 |

| Pippi 2006, Italy(17) | 53 | 28 (52.8) | 13 - 15 |

| Buchner et al. 2006, USA(18) | 1088 | 826 (75.9) | |

| Olgac et al. 2006, Turkey(19) | 527 | 109 (20.7) | 67 - 42 |

| Ladeinde et al. 2005, Nigeria(20) | 319 | 8 (2.5) | |

| Adebayo et al. 2005, Nigeria(21) | 318 | 7 (2.2) | |

| Fernandes et al. 2005, Brazil(23) | 340 | 85 (25) | 52 - 33 |

| Tamme et al. 2004, Estonia(24) | 75 | 26 (34.67) | 14 - 12 |

| Ogunsalu 2003, Jamaica(47) | 80 | 10 (12.5) | |

| Ochsenius et al. 2002, Chile(27) | 362 | 162 (44.7) | 92 - 71 |

| Santos et al. 2001, Brazil(45) | 127 | 64 (50.7) | |

| Lu et al. 1998, China(29) | 759 | 51 (6.7) | 37 - 14 |

| Mosqueda-Taylor et al.1997, Mexico(30) | 349 | 121 (34.67) | 63 - 49 |

| Odukoya 1995, Nigeria(32) | 289 | 12 (4.15) | |

| Daley et al., 1994, Canada(33) | 392 | 202 (51.53) | 74 - 128 |

| Günham et al. 1990, Turkey(34) | 409 | 74 (18.1) | 38 - 36 |

| Wu et al. 1985, China(48) | 68 | 5 (7.35) | |

| Happonenet al. 1982, Finland(46) | 171 | 88 (51.46) | |

| Regezi et al. 1978, USA(43) | 706 | 473 (67) | 214 - 259 |

→ data according to the 2005 WHO classification (CheratocisticOdontogenic Tumors are comprised).

Since not all the reviewed papers reported all epidemiological features on ODs, each feature was evaluated in a different numerical sample.

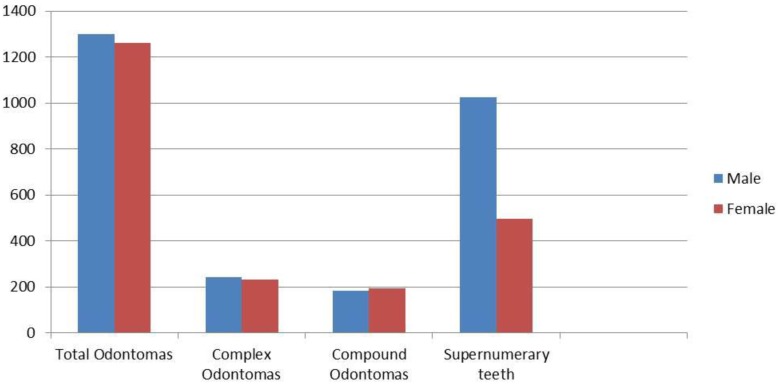

CxOds were slightly more frequent than CpODs (1:0.96; Table 1). OD male/female (M/F) ratio was variously reported in the literature, for example from Egypt with a 0.37:1 ratio,11to Japan with a 1:0.65 ratio.22However, if data from different authors are pooled, M/F ratio gets close to 1:1 (50.70%/49.30%; Table 1, Figure 1) and this was true for CpODs as well as for CxODs. Overall, there is no evidence of sex-biased incidence for ODs.

Figure 1.

Odontomas and Supernumerary teeth by gender.

Among the cases in which the OD type incidence was reported for each gender (852 cases), CxODs were slightly more frequent than CpODs in both genders (about 57%/54,8%; Table 1).

In a sample of 2496 cases, the age of patients at the time of OD diagnosis ranged from 1 to 90 with a mean age of 22.19 ± 3.9 years, however, CxODs were found at an earlier age (19.25±2,9) than CpODs (25,14±4.8; total number of ODs 1251; p=0.0004; IC= 95%; Table 1).

Supernumerary teeth

The incidence of SPNs was 1.5% (770 cases/51130 examined patients; Table 4). The worldwide reported incidence, however, was quite different from one study to another, probably due to differences in the evaluated samples (school samples, general dentistry samples, orthodontic samples or paediatric dentistry samples) and/or in the evaluation methods used (radiological or clinical).

Table 4.

Supernumerary teeth (SPNs) by gender, age and prevalence.

| Authors | Sample | Patient n. with SPNs (M-F) | Total n. of SPNs (M-F) | Mean age (years) | Sample age range (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NazargiMahabob et al. 2012, India(50) | 2216 | 21 (14-7) |

27 | 24.6 | |

| Sharma and Sigh 2012, India(51) | 21824 | 300 (224-76) |

385 | 4-14 | |

| Fardi et al. 2011, Greece(52) |

1239 | 23 (14-9) |

17.2±10.8 | ||

| Pippi 2011, Italy(53) |

118 (73-45) |

191 | 5-61 | ||

| Vahid-Dastjerdi et al. 2011, Iran(54) | 1751 | 13 (6-7) |

14 | 12.5 | 9-27 |

| Schumuckli et al. 2010, Swiss(55) | 3004 | 44 | 6-15 | ||

| Esenlik et al. 2009, Turkey(56) | 2599 | 69 (35-34) |

84 (42-42) |

8.6±0.23 | |

| Anthonappa et al. 2008, China(57) | 208 (157-51) |

283 | 7.3±2.7 | 2.1-15.2 | |

| de Oliveira Gomes et al. 2008, Brazil(58) | 305 (207-98) |

460 (317-143) |

9.3 | 3.7-16 | |

| LecoBerrocal et al. 2007, Spain(59) | 2000 | 21 (15-6) |

24 | 20.2 | 7-34 |

| Harris and Clark 2008, USA(60) | 1700 | 39 (23-16) |

64 (35-29) |

12-18 | |

| Fernández-Montenegro et al. 2006, Spain(61) | 36057 | 102 (60-42) |

147 | 17.11±10.53 | 5-56 |

| Gabris et al. 2006, Hungary(62) | 2219 | 34 | 40 | ||

| Salcido-Garcia et al. 2004, Mexico(63) | 2241 | 72 (39-33) |

103 | 14.4 | 2-55 |

| Rajab and Hamdam2002,Jordan(64) | 152 (105-47) |

202 (148 -54) |

10.1±1.9 | 5-15 | |

| Miyoshi et al. 2000, Japan(65) | 8122 | 4 | 5 (5-0) |

3-6 | |

| Salem 1989, Saudi Arabia(66) | 2393 | 12 (8-4) |

12 | 4-12 | |

| Davis 1987, China(67) | 1093 | 30 (26-4) |

12 | ||

| Luten 1967, USA(68) | 1558 | 32 (18-14) |

36 (20-16) |

1-9 |

SPNs were more common in males than in females (67.5% versus 32.5%; Table 4) with a 1:0.48 ratio (1026/495).

The age of patients at the time of diagnosis ranged from 1 to 61, with a mean age of 14.13±5.6 years (984 cases; Table 4).

In a selected sample of 1176 cases, 1 SPN occurred in 72.6% of cases 2 SPNs in 23% and 3 or more SPNs in 4.4% (Table 5).

Table 5.

Supernumerary teeth (SPNs) by patients (Pts) and degree of eruption.

| Authors | n. SPNs - Pts |

Pts with 1 SPN | Pts with 2SPNs | Pts with 3 or more SPNs | Erupted SPNs | Un-erupted SPNs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sharma and Sigh 2012, India(51) | 385 - 300 | 237 | 60 | 3 | 135 | 250 |

| VahidDastjerdi et al. 2011, Iran(52) | 14 - 13 | 12 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Pippi 2011, Italy(53) | 191 - 118 | 70 | 38 | 10 | 28 | 163 |

| Esenlik et al. 2009, Turkey(54) | 84 - 69 | 54 | 15 | 0 | 22 | 62 |

| Anthonappa et al. 2008, China(57) | 283 - 208 | 128 | 80 | 48 | 235 | |

| de Oliveira Gomes 2008, Brazil(58) | 460 - 305 | 192 | 94 | 19 | 107 | 353 |

| LecoBerrocal et al. 2007, Spain(59) | 24 - 21 | 1 | 23 | |||

| Harris and Clark 2008, USA(60) | 64 - 39 | 25 | 10 | 4 | ||

| Fernández-Montenegro et al. 2006, Spain(61) | 147 - 102 | 79 | 15 | 8 | 20 | 127 |

| Gabris et al. 2006, Hungary(62) | 40 - 34 | 28 | 6 | 0 | ||

| Rajab and Handam 2002, Jordan(64) | 189 - 152 | 117 | 28 | 7 | 50 | 139 |

| Salem 1989, Saudi Arabia(66) | 12 - 12 | 12 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Davis 1987, China(67) | 42 - 30 | 3 | 4 | |||

| Luten 1967, USA(68) | 36 - 32 | 28 | 4 | 0 | 14 | 22 |

Topographic distribution of odontomas and supernumerary teeth

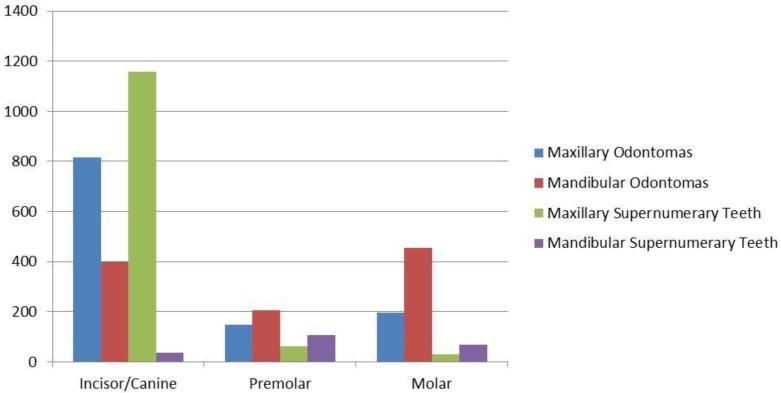

ODs occurred slightly more frequently in the upper jaws (1730 cases) than in the mandible (1583 cases; Table 6, Figure 2). Location in the different tooth areas was referred only for 2226 ODs. In the upper jaw ODs were more frequently located in the incisive-canine area (817 cases), while in the mandible they more frequently affected the molar region (455 cases; Table 6, Figure 2). As for the location of each OD type, it was reported only for a low number of cases (660 CxODs and 578 CpODs). CxODs more frequently occurred in the incisive-canine area of the upper jaw (165 cases) and in the molar area of the mandible (247 cases), while CpODs were more frequently located in the incisive-canine areas of both jaws (Table 6, Figure 2).

Table 6.

Complex (Cx) and Compound (Cp) Odontomas by location.

| Authors | Maxilla | Mandible | Max/Mand Ratio (Cx)(Cp) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior | Posterior | NS | Anterior | Posterior | NS | ||||

| Incisive-Canine (Cx)(Cp) | Premolar (Cx)(Cp) | Molar (Cx)(Cp) | Incisive-Canine (Cx)(Cp) | Premolar (Cx)(Cp) |

Molar (Cx)(Cp) |

||||

| Soluk-Tekkesin et al. 2011, Turkey(8) | 34 (12)(19) 3mix | 9 (3)(6) |

12 (10)(2) |

23 (6)(17) |

11 (6)(5) |

71 (62)(8) 1mix |

0.52:1 (0,34:1) (0.9:1) |

||

| Osterne et al. 2011, Brazil(9) | 13 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 1:0.7 | ||

| Saghravanian et al. 2010, Iran(10) | 9 | 14 (+1 peripheral) | 2 | 18 | 1:0.9 | ||||

| Tawfik and Zyada 2010, Egypt(11) |

2 (1)(1) |

1 (0)(1) |

0 | 6 (2)(4) |

1 (0)(1) |

1 (1)(0) |

0.4:1 (0.3:1) (0.4:1) |

||

| El- Gehani et al. 2009, Libya(12) |

8 (4)(4) |

0 | 0 | 7 (1)(6) |

2 (0)(2) |

12 (5)(7) |

0.38:1 (0.67:1) (0.27:1) |

||

| da Silva et al. 2009, Portugal(13) |

16 (0)(16) |

7 (0)(7) |

5 (3)(2) |

12 (4)(8) |

5 (5)(0) |

3 (2)(1) |

1:0.7 (0.27:1)(1:0.36) |

||

| Luo and Li 2009, China(14) |

30 (14)(16) | 5 (1)(4) |

5 (3)(2) |

12 (5)(7) |

2 (0)(2) |

26 (24)(2) |

1:1 (0.62:1) (1:0.5) |

||

| Avelar et al. 2008, Brazil(15) |

31 | 23 | 1:0.74 | ||||||

| Jing et al. 2007, China(16) |

11 (6)(5) |

6 (5)(1) |

14 (13)(1) |

10 (6)(4) |

12 (8)(4) |

19 (15)(4) |

6 (5)(1)1 |

0.66:1 (0.7:1) (0.54:1) |

|

| Pippi 2006, Italy(17) |

6 (0)(6) |

1 (1)(0) |

2 (2)(0) |

10 (5)(5) |

5 (3)(2) |

3 (2)(1) |

12 | 0.47:1 (0.3:1) (0.67:1) |

|

| Buchner et al, 2006, USA(18) |

161 | 57 | 109 | 109 | 1:1 | ||||

| Olgac et al. 2006,Turkey(19) | 30 (12)(18) | 5 (0)(5) | 5 (5)(0) | 16 (7)(9) | 9 (5)(4) | 44 (38)(6) | 0.58:1 (0.34:1) (1:0.83) |

||

| Ladeinde et al. 2005, Nigeria(20) |

2 | 5 | 0.4:1 | ||||||

| Tomizawa 2005, Japan(22) |

26 | 13 | 1:0.5 | ||||||

| Fernandes et al. 2005, Brazil(23) |

37 (21)(16) | 11 (7)(4) |

5 (4)(1) |

(4)3 (3)3 |

13 (9)(4) |

5 (2)(3) |

7 (5)(2) |

1:0.47 (1:0.5) (1:0.43) |

|

| Tamme et al. 2004, Estonia(24) | 7 (4)(3) |

5 (2)(3) |

1 (0)(1) |

4 (2)(2) |

6 (4)(2) |

2 (2)(0) |

14 | 1:1 (0.75:1) (1:0.71) |

|

| Amado-Cuesta et al. 2003, Spain(25) | 34 | 27 | 1:0.8 | ||||||

| Hisatomi et al. 2002, Japan(26) |

33 (7)(26) |

5 (2)(3) |

10 (7)(3) |

26 (6)(20) |

14 (5)(9) |

14 (13)(1) |

0.8:1 (0.6:1) (1:0.94) |

||

| Ochsenius et al. 2002, Chile(27) |

77 (36)(41) |

5 (1)(4) |

12 (9)(3) |

(5)3 (1)3 |

22 (13)(9) |

12 (5)(7) |

2 8 (22)(6) |

1:0.66 (1:0.87) (1:0.46) |

|

| Miki et al. 1999, Japan(28) |

15 (5)(10) |

5 (3)(2) |

13 (3)(10) |

14 (11)(3) |

0.74:1 (0.57:1) (0.92:1) |

||||

| Lu et al. 1998, China(29) |

8 (4)(4) |

5 (4)(1) |

9 (8)(1) |

3 (2)(1) |

8 (6)(2) |

15 (11)(4) |

3 (2)(1)1 |

0.84:1 (0.76:1) (0.75:1) |

|

| Mosqueda-Taylor et al. 1997, Mexico(30) |

56 (15)(41) |

9 (6)(3) |

7 (5)(2) |

13 (1)(12) |

10 (8)(2) |

17 (14)(3) |

1:0.56 (1:0.88) (1:0.37) |

||

| Macdonald-Jankowski 1996, China(31) |

11 (7)(4) |

2 (1)(1) |

0 | 10 (1)(9) |

1 (0)(1) |

2 (2)(0) |

1:1 (1:0.37) (05:1) |

||

| Odukoya 1995, Nigeria(32) | 4 | 4 | 1:1 | ||||||

| Günham et al. 1990, Turkey(34) |

28 (12)(16) | 2 (1)(1) |

5 (2)(3) |

14 (3)(11) |

6 (4)(2) |

19 (16)(3) |

0.9:1 (0.65:1) (1:0.8) |

||

| Kaugars et al. 1989, USA(35) |

119 | 25 | 35 | 86 | 45 | 41 | 1:0.96 | ||

| O'Grady et al. 1987, Australia(36) |

47 | 8 | 16 | 14 | 8 | 25 | 1:0.66 | ||

| Or and Yucetas 1987, Turkey(37) |

13 (5)(8) |

7 (3)(4) |

2 (1)(1) |

5 (1)(4) |

9 (4)(5) |

13 (6)(7) |

0.8:1 (0.8:1) (0.8:1) |

||

| Pizzirani and Gemesio 1984, Italy(38) | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 6 | 0.7:1 | ||

| Toretti et al. 1984, UK(39) | 83 | 79 | 1:0.95 | ||||||

| Bodin et al. 1983, Sweden(40) | 30 | 35 | 0.86:1 | ||||||

| Slootweg 1981, The Netherlands(41) | 71 | 55 | 1:0.77 | ||||||

| Regezi 1978, USA(43) | 177 | 26 | 32 | 80 | 26 | 55 | 1:0.68 | ||

| Budnick 1976, USA(44) | 61 | 5 | 19 | 15 | 6 | 21 | 1:0.49 | ||

1: Complex and Compound Odontomas at the mandibular angle location; 2: Compound Odontomas at the retro-molar location; 3: not specified location; 4: Compound Odontomas at the mandibular angle location.

Figure 2.

Odontomas and Supernumerary teeth by location.

The total number of SPNs obtained from the present literature review was 2116. In a selected sample of 1665 SPNs, 85% of them were located in the upper maxilla, while 15% was in the mandible (Table 7). The upper incisive-canine area was involved in the great majority of cases (69.5%; 1157 cases); in the mandible, SPNs more frequently affected the premolar area (42%) which represented the second most frequent location in the mouth. The palatal/lingual location showed a higher incidence of SPNs (77.2%) than the buccal and the midline locations (7.8% and 15%, respectively; Table 8). Lastly, when dividing SPNs according to different types, the major incidence of the conical type is evident (56.6%; 1023/1808 cases) compared to the others (supplementary 19.6%, tuberculate 17.8%, mis-shaped/odontoma-like 5.2% and infundibuliform 0.7%; Table 9).

Table 7.

Supernumerary teeth by location.

| Authors | Maxilla | Mandible | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | C | P | M - DM | I | C | P | M - DM | |

| NazargiMahabob et al. 2012, India(50) | 12 | 0 | 2 | 0-4 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0-3 |

| Pippi 2011, Italy(53) | 92 | 0 | 19 | 10-15 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 38-11 |

| Vahid-Dastjerdi 2011, Iran(54) | 11 | 3 | ||||||

| Esenlik et al. 2009, Turkey(56) | 56 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 12 | 0 |

| Anthonappa et al. 2008, China(57) | 271 | 0 | 2 | 2-0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0-0 |

| de Oliveira Gomes et al. 2008, Brazil(58) | 399 | 12 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 30 | 0 |

| LecoBerrocal 2007, Spain(59) | 6 | 1 | 2 | 0-8 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0-1 |

| Harris and Clark 2007, USA(60) | 15 | 0 | 9 | 0-20 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0-8 |

| Fernández-Montenegro et al. 2006, Spain(61) | 72 | 1 | 9 | 4-24 | 2 | 3 | 26 | 4-2 |

| Gabris et al. 2006, | 28 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unghery(62) | 2 | 6 | ||||||

| Salcido-Garcia et al. 2004, Mexico(63)* | 60 | 43 | ||||||

| Rajab and Handam 2002, Jordan(64) | 181 | 3 | 5 | 1 - 0 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 0 |

| Luten 1967, USA(68) | 33 | 3 | ||||||

I: incisor area; C: canine area; P: premolar area; M - DM: molar - distomolar areas.

* Maxillary + Mandibular supernumerary teeth: I+C=53; P=38; M=12.

Table 8.

Supernumerary teeth by position

| Authors | n. | Sagittal/Frontal plane | Axial plane | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | T | N-O | In | UC | O | B | E/W- A | ||

| Pippi 2011, Italy(53) | 191 | 131 | 19 | 41 | |||||

| Esenlik et al. 2009, Turkey(56) | 84 | 6 | 0 | 58 | 14 M + 6 D | ||||

| Anthonappa et al. 2008, China(57) | 283 | 135 | 38 | 93 | 17 | 224 | 6 | 51 | |

| de Oliveira Gomes et al. 2008, Brazil(58) | 460 | 80 | 3 | 363 | 141 | 388 | 22 | 50 | |

| Fernández-Montenegro et al. 2006, Spain(61) | 145 | 6 | 68 | 51 | 20 | ||||

| Rajab and Handam 2002, Jordan(64) | 202 | 19 | 13 | 157 | 13 | 172 | 2 | 28 | |

I: inverted; T: transverse; N-O: normal orientation; In: inclined; UC: unclassified; O: oral;

B: buccal; E/W-A: erupted/well alligned; M: mesio-inclined; D: distal-inclined.

Table 9.

Supernumerary teeth (SPNs) by morphology.

| Authors | SPNs | Supplemental | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n. | C | T | I | M-S /O-L | I-F | C-F | P-F | M-F | ||

| Sharma and Sigh 2012, India(51) | 385 | 230 | 55 | 30* | 70 | |||||

| Pippi 2011, Italy(53) | 191 | 70 | 29 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 2 | 41 | 18 | |

| Vahid-Dastjerdi et al. 2011, Iran(54) | 14 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 3 | |||||

| Schmuckli et al. 2010, Swiss(55) | 44 | 31 | 2 | 10 | 1 | |||||

| Esenlik et al. 2009, Turkey(56) | 84 | 42 | 2 | 40 | ||||||

| Anthonappa et al. 2008, China(57) | 283 | 202 | 31 | 17 | 33 | |||||

| de Oliveira Gomes et al. 2008, Brazil(58) | 460 | 205 | 178 | 77 | ||||||

| Fernández-Montenegro et al. 2006, Spain(61) | 145 | 87 | 3 | 20* | 35 | |||||

| Rajab and Handam 2002, Jordan(64) | 202 | 151 | 24 | 13 | 14 | |||||

C: conoid; T: tuberculated; I: infundibuliform; M-S/O-L: mis-shaped/odontome-like;

I-F: incisiviform; C-F: caniniform; P-F: premolariform; M-F: molariform.

* Rudimentary/dismorphic/molariform.

When observing their status within the alveolar process, the great majority of SPNs (85%; 1082/1273 cases) was impacted, and only a minority (15%; 191/1273 cases) was erupted (Table 6).

Pathological and clinical features

The most common OD-related pathologies were permanent tooth retention and eruptive delay (46, 46%), followed by bone swelling (11.39%), cysts (11, 12%) and infection/pain (3, 77%; Table 10).

Table 10.

Odontomas by more frequent complications/associated pathologies.

| Authors | n. | Impaction or delayed eruption | Bone swelling | Cysts | Infection/pain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soluk-Tekkesin et al.2011, Turkey(8) | 160 | 13 (7Cx + 5Cp + 1Mx) | 12 (7Cx + 5Cp) | 8 (7Cx + 1Cp) | |

| da Silva et al. 2009, Portugal(13) | 48 | 33 (7Cx + 26Cp) | 2 | 3 | |

| Pippi 2006, Italy(17) | 28 | 15 (5Cx + 10Cp) | 7 | ||

| Tomizawa et al. 2005, Japan(22) | 39 | 19 | 1 | ||

| Amado-Cuesta et al.2003, Spain(25) | 61 | 45 | 31 | 6 | |

| Hisatomi et al. 2002, Japan(26) | 103 | 76 (27Cx + 49Cp) | |||

| Miki et al. 1999, Japan(28) | 47 | 3 | 12 | 9 | |

| Macdonald-Jankowski et al. 1996, China(31) | 40 | 26 (11Cx + 15Cp) | 4 | 6 (5Cx + 1Cp) | 10 |

| Kaugars et al. 1989, USA(35) | 351 | 167 | 27 | 97 | |

| Or and Yucetas 1987, Turkey(37) | 49 | 8 (2Cx + 6Cp) | 6 (3Cx + 3Cp) | 5 (3Cx + 2Cp) | |

| Bucci et al. 1983, Italy(49) | 75 | 34 | 22 | 4 | |

| Budnick 1976, USA(44) | 114 | 69 | 31 |

Cx = complex; Cp = compound; Mx = mixed.

As for SPNs, tooth retention/eruption delay accounted for 45, 29%, diastemas/dislocations/malpositions for 7, 1%, and cysts for 5, 7% (Table 11).

Table 11.

Patients with supernumerary teeth (SPNs) by more frequent complications/associated pathologies.

| Authors | Patients (SPNs) |

Un-eruption of permanent teeth | Cysts | Malposition/ crowding of teeth | Spacing/ diastema | Malformation/root resorption of permanent teeth |

Fusion with a permanent tooth | Odontoma |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pippi 2011, Italy(53) | 118 (191) | 81 (40) | 7 (7) | 7 (7) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | |

| Esenlik et al. 2009, Turkey(56) | 69 (84) | 18 (18) | 6 (6) | |||||

| Anthonappa et al. 2008, China(57) | 208 (283) | 1 | 112 | 14 | ||||

| de Oliveira Gomes et al. 2008, Brazil(58) | 305 (460) | 155 | 227 | 64 | 18 | |||

| LecoBerrocal et al. 2007, Spain(59) | 21 (24) | (1) | 4 (4) | (9) | (3) | |||

| Fernández-Montenegro et al. 2006, Spain(61) | 102 (145) | (43) | (2) | (6) | (2) |

Discussion

Epidemiology and clinical signs

From a nosological point of view, ODs and SPNs are still classified as distinct entities, although from an etio-pathogenetic and, even more, from a clinical point of view, they seem to be the expression of the same pathologic process, malformative or hamartomatous. Actually, the analysis of the literature data shows some similarities between ODs and SPNs concerning topographic distribution and pathologic manifestations.

Although the overall SPNs incidence was almost 2.5 times more than ODs, most reports on SPNs concerned selected samples in which the incidence was certainly higher than in the general population. On the other hand, the real incidence of ODs is probably higher since reported data come from histological reviews so it is possible that some CpODs, likely due to their morphological similarities with SPNs,17have not been included in the reports because they were not evaluated histologically. Moreover, it is likely that some CxODs were not subjected to surgical excision since they did not determine clinical problems, especially those in the posterior area of the mandible, which are also the most frequent. Finally, the total number of ODs could be higher if all ameloblastic fibro-odontomas were considered as developing ODs, especially those in young people, which will be discussed later.

Topographic distribution in dental arches does not seem to be totally similar for the two conditions, but shows common features. They all are commonly located in upper jaw,17, 53although SPNs more often than ODs; SPN are more frequently found in the incisive, premolar and disto-molar regions, while ODs are more uniformly distributed among the different areas with only a slightly higher incidence in the incisive-canine area, which is more evident in the upper jaw. Therefore, SPNs mainly involve the areas corresponding to the extremities of the primitive as well as the secondary dental laminas and above all the mesial extremity of the primitive dental lamina, that is, the pre-maxillary area, particularly in the incisive region.

ODs and SPNs are usually asymptomatic although often associated with the same pathologic manifestations that are mainly related either to the lack of space for the regular eruption of normal permanent teeth or to their inflammatory or cystic complications with the involvement of neighboring anatomical structures (maxillary sinuses, vascular-nervous bundles, nasal cavities).

Eruption disturbances of permanent teeth are therefore the most frequent and important pathological complications of both ODs and SPNs, especially tooth retention, reported from 6.38%28to 48,73%22for ODs and from 4.76%59to 50,82%58for SPNs. In particular, among pre-maxillary SPNs, tuberculates and supplementaries (incisor-like) are more frequently associated with tooth impaction than conoids.53As for ODs, tooth impaction is more frequently associated with the compound ones than with the complex ones.17

Finally, although eruption is frequent as far as SPNs are concerned, due to their normal root structure and morphology, it can occur anyway,8although rarely, also in compound69as well as complex ODs.8, 70, 71

From an analysis of the epidemiological data reported by the international literature, many elements support the assumption that SPNs and ODs have the same origin and may constitute aspects of the same phenomenon: high frequency of occurrence almost in the same jaw areas; same type of pathologic sequelae; greater frequency at a young age, although earlier for SPNs than for ODs; to be formed by all completely differentiated dental tissues.

The only real difference as far as epidemiology is concerned is the different incidence in relation to gender since SPNs appear more common in males than in females, whereas ODs appear to be almost equal in both genders. This different incidence may be due to the fact that, after childhood, men tend to have fewer checkups than women, with a consequent missed diagnosis, also due to the lack of symptoms, as confirmed by the Italian ISTAT statistical database which in 2005 reported a higher percentage of women (41.2%) than men (38.1%) undergoing dental care over 18 years of age, especially in the 18-24 age range (F=49.1%; M=39.6%),72in which ODs, specifically CxODs, are usually diagnosed. Moreover, a male predilection has been found for ODs in children (M:F=1.5:1,22M:F=1.2:173), in children and adolescents (M:F=1.2:1),74, 75, and particularly in the primary dentition (M:F=1.6:1)76, although an inverse ratio has also been reported in Nigerian children and adolescents (M:F=1:2).21

Pathogenesis

It is nowadays accepted that CpODs and SPNs derive from the proliferation of clusters of epithelial cells arising from a localized dental lamina hyperactivity related to genetic or teratogenic stimuli. Control factors and stimuli deriving from mesenchymal tissue located around dental lamina or/and papillae seem to condition these cells to develop toward atrophy or towards more or less organized dental structures. The origin of these inductive stimuli is not completely known although they are certainly time and site related.

The Field Theory, proposed by Butler in 193977, was an attempt to account for the common features of teeth within a morphological class postulating that the most mesially-positioned tooth in each class is usually the most phenotypically stable. According to the Field Theory, the mesenchymal influence on epithelial cells of each morphologic tooth class reduces from the incisor to the molar area. If on the one hand this can explain the higher incidence of agenesia as well as the smaller dimensions of the distal element of each morphologic tooth class, on the other hand it can justify the extreme rarity of supplementary upper canines, in comparison with the relative higher incidence of ODs in the same site (Tables 6, 7). This different incidence of events in the upper canine area can be put in relation to the poor influence that incisor and premolar morphogenetic fields exert to condition the morpho-structural evolution of epithelial cells in excess located in that transitional area.

On the other hand, the different period in which the clusters of epithelia cells start to proliferate can explain the different degrees of root structural maturation and the mineralization defects rather frequently present on the enamel surface of SPNs and ODs. Actually, the complete or almost complete root mineralization of the conoids78may be related to their early occurrence which on the one hand does not allow the conoid crown to develop completely, influenced by the mesenchymal inductive mechanisms of the incisor morphogenetic field and, on the other hand, allows their root to reach a high degree of development.79

In the same manner, the incomplete root mineralization of the tuberculates may be related to their later occurrence,78which is contemporary or more often following that of permanent incisors. On the other hand, tuberculate morphology is probably due to the poor influence exerted by incisor morphogenetic field which has already exhausted its inductive potentiality.79

As for the supplementary teeth, they develop at the same site and start to mineralize at the same time or just shortly before normal permanent homologous teeth,80so that they feel the same inductive stimuli as far as quality and intensity are concerned. For this reason, supplementary teeth crown morphology is often exactly like that of normal permanent incisors and they develop at the same site where normal teeth should erupt, interfering with their eruption. It is also possible that each supplementary tooth develops from a duplication of a single tooth bud due to environmental stimuli, although this seems unlikely in the case of the contemporary occurrence of two or three supplementary teeth in the same area, incisive and especially premolar, also considering that in those cases all teeth, normal and supernumeraries, have normal dimensions.

Finally, it is important to observe that CpODs are associated to tooth retention more than the complex ones (111/59; Table 10) and that CpODs are found at an earlier age than the CxODs (Table 1).79If it is considered that CpODs more frequently involve the pre-maxilla and that they are diagnosed at an earlier age, it can be supposed that their development occurs earlier,41as early as the pre-eruptive phase of dentition or at the beginning of the pre-functional eruptive phase. This can justify the considerable interference of CpODs with tooth eruption as well as their greater morphologic differentiation.

On the other hand, CxODs are diagnosed later than CpODs, are slightly more frequent in the lateral-posterior areas (Table 6), where the differentiation of dental tissues ends later, and less frequently cause tooth retention (Table 10). Therefore, it is possible that they develop later and that may represent a morphologically less differentiated expression of the same hyper-productive process which, in its best developed expression, is constituted by completely structured and morphologically normal dental elements, that is the supplementary teeth.79Actually, the clinical behaviour of ODs is different from that of all benign tumours since they stop increasing at a certain point, they do not infiltrate but only squeeze and displace the neighbouring structures and tissues, and finally, they do not recur or move towards a malignant transformation.

A similar hypothesis on CpOD origin was proposed by Philipsen and co-workers4who suggested considering this lesion as a real malformation probably due to a localized hyperactivity of the dental lamina similarly to supernumerary teeth. On the other hand, these authors4suggested that the CxOD belongs to a so-called hamartomatous line of development of the mixed odontogenic tumours, which they also defined as a developing complex odontoma line, including some ameloblastic fibromas, that is those occurring before the completion of the odontogenesis (about 20 years of age), and the ameloblastic fibro-odontoma belong, in that these lesions seem to represent early stages of the developing complex odontoma. The proper neoplastic line of odontogenic tumours includes only the ameloblastic fibroma and the related ameloblastic fibrodentinoma. However, not all cases of ameloblastic fibro-odontoma should be considered hamartomatous since some cases have shown neoplastic behaviour, also malignant, although it is difficult to distinguish between a developing odontoma and a true neoplastic ameloblastic fibro-odontoma.81Actually, differences exist in location and age distribution at the time of diagnosis between complex and compound ODs, the first ones being more frequent in the lateral posterior areas of the jaws and diagnosed at a slightly earlier age than the second ones. However, transitional or mixed cases of ODs in which both types of ODs coexist, have sometimes been found8, 22to show that a real different categorization of the two types of OD cannot be justified, although it seems to be correct to separately record each kind of OD for epidemiological purposes, as Philipsen and co-workers4suggested. Furthermore, a different pattern of matrix protein expression, particularly as far as amelotin and amelogenin are concerned, has been found by immuno-histochemical analysis, to distinguish complex odontomas from all other odontogenic tumours, including ameloblastic fibroma.82Since these proteins are immuno-detected in different phases of amelogenesis, their simultaneous expression has been explained by the presence of ameloblasts in various stages of differentiation which is typical of the normal odontogenic process. The pattern of protein distribution (linear between the enamel matrix and ameloblasts) was similar to that described in the normal rat tooth germ to further suggest a common origin for ODs and SPNs. Similar data were already found by Crivelini et al. in 200383using different antibodies for cytokeratin polypeptides and vimentin. These authors found differences with ameloblastic fibromas, whose immuno-phenotype resembled that of dental lamina, to CpODs, whose immuno-histochemical findings resembled those of the enamel organ of the dental germ. The authors suggested that in ODs, pre-ameloblasts and ameloblasts did not reach complete differentiation so that some enamel matrix remained unable to undergo complete mineralization. This could explain a various degree of morpho-differentiation in ODs.

Another interesting immuno-histochemical difference between ODs and ameloblastomas was more recently found by Kiyoshima et al.84as to thymosin β4 (Tβ4), a member of the actin-binding polypeptide family, which has been shown to carry out different functions in several tissues and cell types, including carcinomas. Actually, Tβ4 immuno-reactivity was significantly higher in ameloblastomas than in both types of ODs. In the latter, all calcified materials associated with epithelial cells and the dentin matrix were negative for Tβ4, while only pre-secretory ameloblasts at the epithelium-enamel interface as well as few cells of the odontoblastic layer, located in the pulpal tissue faced with predentin matrix, showed positive staining for Tβ4. Since the high Tβ4 expression in ameloblastomas was always similar in samples taken from the same patient at different times and tended to be higher in the peripheral polarized cells than in the central cells of the same nest, Tβ4 expression seemed to be related with tumour progression through its anti-apoptotic activity.84Moreover, it is peculiar that ameloblastic fibro-odontomas showed a Tβ4 pattern of distribution similar to ameloblastomas as to epithelial nests or strands while similar to ODs as to dental hard tissues, suggesting that both lines of development, neoplastic and hamartomatous, may occur in this lesion.

Similar observations have already been made histologically in CpODs' undemineralized sections by Piattelli and Trisi85who suggested that the altered enamel appearance they observed could be due to qualitative, quantitative and temporary modifications in enamel organ function with differences in mineralization and maturation of ameloblasts. Moreover, two different types of dysplastic calcifying cells, which could represent two different stages of dysplastic epithelial ameloblastic cells, derived from the stellate reticulum or from the intermediate layer of the enamel organ, were detectable in the un-demineralized material producing two different types of tissue other than normal dental mineralized tissue.85

As far as enamelysin is concerned, differences were also reported by Takata et al.86who found a strongly positive pattern within the immature enamel of the tooth germ during the late bell stages as well as in the enamel matrix with inductive hard tissue formation typically present in ODs and ameloblastic fibro-odontomas.

On the other hand, a similar distribution of amelogenins, keratins, collagen types III and IV, vimentin, fibronectin, osteonectin and osteocalcin has been shown in children, in comparisons between normal human teeth and selected areas of mixed odontogenic tumours, which are ameloblastic fibromas, ameloblastic fibro-odontomas and complex odontomas, supporting the concept that these pathologies represent stages of evolution of a single pathologic process whose phenotype is characterized by well-differentiated odontogenic cells, such as in normal teeth.87The different expression of enamel-associated genes can therefore represent different stages of tumour differentiation, also within the same histological type, in relation to different cell maturation degrees and tumour morpho-differentiation, as already suggested by Dodds et al.88

A genetic component in SPN aetiology has already been suggested by the report of many family cases, also in two monozygotic twins whose mother had already been treated for SPNs during childhood,89by Brooks' observation7that the prevalence of SPNs in the population sample of first-degree relatives was greater than in the child population of his study, and by the frequent occurrence of SPNs in several hereditary syndromes90-134(Table 12). SPNs have also been found in association with localized gingivitis/parodontitis/aggressive periodontitis either in several sporadic case reports135, 136or in Noonan syndrome,121a heterogeneous genetic condition in which not only the Ras/MAPK (rat sarcoma/mitogen-activated protein kinase), which is a product of the PTPN11 (protein Tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 11) gene, has been shown to be mutated but also many other genes and certainly others which still have to be identified. This further suggests an association between multiple genetic and non-genetic factors in aetiology of the two pathological conditions.

Table 12.

Main hereditary syndromes in which supernumerary teeth were found.

| Syndromes | Authors |

|---|---|

| Apert Syndrome | VadiatiSaberi&Shakoorpour 2011(90) |

| Autosomal-dominant Ankyloglossia | Acevedo et al. 2012(91) |

| Cleft Lip-Alveolus-Palate | Lai et al 2009, (92)Wu et al. 2011(93) |

| Cherubism | Schindel et al. 1974(94) |

| Cleidocranial Dysplasia | Ida et al. 1981, (95)Kreiborg and Jensen 1990,(96) Jensen and Kreiborg 1990(97), Kreiborg et al. 1999,(98) Cooper et al. 2001(99) |

| Down Syndrome | Chow and O'Donnel 1997(100) |

| Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome | Majorana and Facchetti 1992,(101)Melamed et al. 1994,(102)Ferreira O Jr et al. 2008,(103)Premalatha et al. 2010(104) |

| Ekman-Westborg-Julin Syndrome | Yoda et al. 1998(105) |

| Ellis-van Creveld Syndrome | Brindley et al. 1975,(106)Prabhu et al. 1978,(107)Hattab et al. 1998,(108)Cahuana et al. 2003(109) |

| Familial Adenomatous Polyposis, including Gardner's Syndrome | Fader et al. 1962,(110) McFarland et al. 1968,(111) Wolf et al 1986,(112)Wijn et al. 2007(113) |

| Fabry-Anderson Disease | Regattieri and Parker 1973(114) |

| IncontinentiaPigmenti | Himelhock et al. 1987(115) |

| Kabuki Make-Up Syndrome | Rocha et al 2008(116) |

| Larsen's Syndrome | Perçin et al. 2002(117) |

| Marfan Syndrome | Khonsari et al. 2010(118) |

| Nance-Horan Syndrome | Walpole et al. 1990,(119)Hibbert 2005(120) |

| Noonan Syndrome | Toureno and Park 2011(121) |

| Otodental Dysplasia | Chen et al. 1988,(122) Van Doorne et al. 1998(123) |

| Pyknodysostosis | Ramaiah et al 2011(124) |

| Robinow Syndrome | Mazzeu et al. 2007(125) |

| Rubinstein Taybi Syndrome | Stalin et al. 2006(126) |

| SOX2 Anophthalmia Syndrome | Numakura et al. 2010(127) |

| Sotos Syndrome | Bale et al. 1985,(128)Raitz and Laragnoit 2009(129) |

| Ttricho-rhino-phalangeal Syndrome | Kantaputra et al. 2008(130) |

| Zimmerman-Laband Syndrome | Chadwick et al 1994,(131)Holzhausen et al.2003(132) |

| Others | Silengo et al. 1993,(133)Nieminen et al 2011(134) |

The rarity of ODs in humans does not allow performing epidemiologic studies to verify such a genetic/etiologic supposition. However, in the last 30 years selected transgenic mice, in which SPNs137and odontogenic tumours138, 139frequently develop, have been used to investigate the complex odontogenic process that yields to the formation of both pathologies as well as of normal teeth. In the light of these studies, a genetic regulation seems therefore important in developing not only SPNs but also ODs, although differences exist in the expression of different genes.

Western blot analysis, in situ hybridization and immuno-histochemistry have been used in addition to histology to search for a possible role of genes, proteins, growth factors, receptors, extra-cellular matrix molecules, and other factors and molecules, in aetio-pathogenesis and morpho-differentiation of odontogenic tumours and SPNs, compared to normal tooth formation.

Observations have suggested that tumour proliferation and growth are principally driven by mesenchymal tumour cells138and that, although enamel does not derive from dental mesenchyma, unlike all other dental structures, dental mesenchyma is able to induce non-odontogenic epithelium to form odontogenic epithelium.140

The existence of a specific pathway of molecule signalling seems therefore important in defining the complex mechanism that controls the acquisition of odontogenic potentialities. The under/over expression of some of these signalling factors/molecules, most of which are still unknown, may influence different development times, aggregation and morpho-differentiation of dental tissues. Actually, many signalling molecules belonging to Hedgehog, FGF, Wnt, TNF, BMP PAX, SHH families and others have been proven to be important in the normal tooth germ development and seem to be able to give rise to supernumerary teeth if inappropriately regulated.141, 142

It is suggestive that in Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP),143an autosomal-dominant disorder, and specifically in Gardner's Syndrome, a FAP variant condition, many affected patients show multiple SPNs and ODs. Specifically, SPNs and ODs have been found approximately in 11-27% and, respectively, in 9.4-83.3% of patients with FAP, although no specific codon mutation has been found to be correlated with SPNs and/or ODs.144Actually, FAP has been shown to result from a mutation in adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) tumour suppressor gene which is known to inhibit Wnt signalling, an important family of proteins including β-catenine and Lef-1, which have been demonstrated to be important in tooth number and development regulation.142, 144Moreover, multiple odontoma-like SPNs have been found in transgenic mice whose oral epithelium expressed a stabilized form of β-catenine141and multiple SPNs have been found to be part of a SOX2 anophthalmia syndrome probably because of the defective inhibitory effect of SOX2 protein on Wnt/β-catenine signalling.127, 145Although a strict correlation between unregulated Wnt signalling and hyperdontia is therefore clearly documented in the literature, no hypotheses have been postulated nor suggestions have been put forward about the development of ODs and their relationship with SPNs in FAP as well as in physiological conditions. In this regard, it is possible that cells developed in excess from the dental lamina epithelium, due to a Wnt signalling inhibition, may lose their normal genetic and morphogenetic control and may develop toward morpho-genetically well-defined SPNs, odontoma-like teeth or real ODs - from compound to complex - in relation to different gradients of molecular genetic control. Moreover, other non-genetic factors, which are environmental, such as foetal, teratogenic, nutritional, traumatic and x-ray related, or epigenetic, such as DNA methylation and histone modifications, may also be involved in the formation of SPNs as already suggested in human Cleidocranial Dysplasia (CCD),144, 146, 147an autosomal-dominant disorder in which the defective RUNX2 related protein seems incapable of preventing excess budding of successional dental laminae,148due to their different pattern of expression in siblings with identical gene mutation in RUNX2146as well as to the highly variable intra-familial expressivity, as specifically concerns presence and number of SPNs, in families with 100% genetic penetrance149in which the dental phenotype seems to be associated with specific mutations in the CBFA1 transcription factor, on chromosome 6p21. Actually, local abundance of odontogenic epithelium has been previously found in peridental tissues of patients with CCD by histological and immuno-histochemical studies.150

Finally, copy number variation, which includes insertion, deletions and inversions of genes, has also been suggested as a possible cause of different phenotypical expression in individuals with CCD having identical gene mutation.147

This pathogenetic hypothesis can also be supported by the sporadically reported simultaneous presence of ODs and SPNs in non-syndromic cases13, 26, 53, 56, 151-153and by many cases of non-syndrome multiple (more than five) SPNs.154-156Moreover, CxODs and supernumerary microdontic teeth have been alternatively found in Otodental Dysplasia,122an autosomal dominant inherited condition whose locus has been mapped to 20q13.1 within a 12-cM critical chromosomal region,157and a CxOD has been found as well in association with 1 SPN in a variant of Ekman-Westborg-Julin Syndrome.105

Several transcription factors, including the LIM homeo-domain (Lhx) family proteins, have been shown to play an important role in tooth development. Denaxa et al.137showed that the deletion of Lhx6 and Lhx7 homeo-box transcription factors in mice resulted in the presence of SPNs in the maxillary incisor domain. Since Lhx6 and Lhx7 expression has been found to persist at later developmental stages of tooth development, it is likely that Lhx6 and Lhx7 LIM homeo-domain proteins are key factors in the complex network of relationships which regulates the acquisition of odontogenic potential by the mesenchyme, allowing developing teeth to progress from the dental lamina to the bud stage. Shibaguchi et al.158have already proposed the role of another member of the Lhx family proteins, the LIM homeo-box 8 (Lhx8), in the regulation of tooth morphogenesis, while Kim et al.159recently demonstrated that LHX8 plays a similar role in the morphogenesis of compound as well as complex ODs and that the Lhx8 gene and protein over-expression in ODs, unlike normal dental stem cells, is associated with a wide spectrum of tooth-like structures characterized by different stages of morpho-differentiation.

Notch signalling mediated by Jagged 2 genes (Jag2) has also been found to play a critical role in normal tooth development and its absence has shown to interfere in the complex network of epithelial-mesenchymal interactions which regulate the expression of genes involved in odontogenesis, of both ameloblastic and odontoblastic components, leading to an abnormal bud morphology with lack of enamel, due to an incorrect BMP and FGF protein regulation of cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis.160

Wright et al.138found three different types of tissue organization in the odontogenic tumours of homozygous TG.AC transgenic mice, with a different yet always positive expression of the k-Ha-ras gene and production of p21 ras oncoprotein, as well as a different tumour development times. Over-expression of the ras p21 protein was also found in human odontogenic tumours by Sandros et al.,161although no odontomas were included in the study sample analyzed by the authors. Furthermore ras p21 expression has been found in the epithelium components of the normal developing human teeth. Expression of ras transgene is also thought to be triggered by chemical or physical local injuries88and, since the proliferation of odontogenic tumour tissues seems to start from the periodontal ligament, it may be hypothesized that any kind of trauma on teeth and tooth bearing areas can activate the ras transgene resulting in stimulation of odontogenic cell proliferation in the periodontal ligament.

In conclusion, from the present review, epidemiological, clinical, immuno-histochemical and genetic data suggest a common origin for SPNs and ODs which appear to be the expression of the same odontogenic hyper-productive process with different gradients of morpho-differentiation, in relation to a time- and site-related signalling pathway of molecules and factors, genetically, non-genetically and epigenetically determined and modulated. Further studies are however required to substantiate this pathogenetic hypothesis.

References

- 1.Kramer IRH, Pindborg JJ, Shear M. WHO histological typing of odontogenic tumours. 2nd ed. Geneva: Spinger-Verlag; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumors. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reichart PA, Philipsen HP. Odontogenic tumors and allied lesions. London: Quintessence Publishing Co Ltd; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Philipsen HP, Reichart PA, Praetorius F. Mixed odontogenic tumours and odontomas. Considerations on interrelationship. Review of the literature and presentation of 134 new cases of odontomas. Oral Oncol. 1997;33:86–99. doi: 10.1016/s0964-1955(96)00067-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saarenmaa L. The origin of supernumerary teeth. Acta Odontol Scand. 1951;9:293–303. doi: 10.3109/00016355109012791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gardiner JH. Supernumerary teeth. Dent Pract. 1961;12:63–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brook AH. A unifying etiological explanation for anomalies of human tooth number and size. Archs Oral Biol. 1984;29:373–378. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(84)90163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soluk Tekkesin M, Pehlivan S, Olgac V. et al. Clinical and histopathological investigation of odontomas: review of the literature and presentation of 160 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70:1358–1361. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osterne RL, Brito RG, Alves AP. et al. Odontogenic tumors: a 5-year retrospective study in a Brazilian population and analysis of 3406 cases reported in the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111:474–481. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saghravanian N, Jafarzadeh H, Bashardoost N. et al. Odontogenic tumors in an Iranian population: a 30-year evaluation. J Oral Sci. 2010;52:391–396. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.52.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tawfik MA. Zyada MM. Odontogenic tumors in Dakahlia, Egypt: analysis of 82 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Gehani R, Orafi M, Elarbi M. et al. Benign tumours of orofacial region at Benghazi, Libya: a study of 405 cases. J Cranio-Maxillofac Surg. 2009;37:370–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.da Silva LF, David L, Ribeiro D. et al. Odontomas: a clinicopathologic study in a Portuguese population. Quintessence Int. 2009;40:61–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo H-Y, Li T-J. Odontogenic tumors: a study of 1309 cases in a Chinese population. Oral Oncol. 2009;49:706–711. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avelar RL, Antunes AA. et al. Odontogenic tumors: clinical and pathology study of 238 cases. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;74:668–673. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)31375-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jing W, Xuan M, Lin Y. et al. Odontogenic tumours: a retrospective study of 1642 cases in a Chinese population. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;36:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pippi R. Benign odontogenic tumours: clinical, epidemiological and therapeutic aspects of a sixteen years sample. Minerva Stomatol. 2006;55:503–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buchner A, Merrell PW, Carpenter WM. Relative frequency of peripheral odontogenic tumors: a study of 45 new cases and comparison with studies from the literature. J Oral Pathol Med. 2006;35:385–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2006.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olgac V, Koseoglu BG, Aksakalli N. Odontogenic tumours in Istanbul: 527 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;44:386–388. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ladeinde AL, Ajayi OF, Ogunlewe MO. et al. Odontogenic tumors: a review of 319 cases in a Nigerian teaching hospital. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;99:191–195. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adebayo ET, Ajike SO, Adekeye EO. A review of 318 odontogenic tumors in Kaduna, Nigeria. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:811–819. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomizawa M, Otsuka Y, Noda T. Clinical observations of odontomas in Japanese children: 39 cases including one recurrent case. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2005;15:37–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2005.00607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernandes AM, Duarte EC, Pimenta FJ. et al. Odontogenic tumors: a study of 340 cases in a Brazilian population. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;34:583–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2005.00357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tamme T, Soots M, Kulla A. et al. Odontogenic tumours, a collaborative retrospective study of 75 cases covering more than 25 years from Estonia. J Cranio-Maxillofac Surg. 2004;32:161–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amado-Cuesta S, Gargallo-Albiol J, Berini-Aytés L. et al. Review of 61 cases of odontoma. Presentation of an erupted complex odontoma. Med Oral. 2003;1:299–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hisatomi M, Asaumi JI, Konouchi H. et al. A case of complex odontoma associated with an impacted lower deciduous second molar and analysis of the 107 odontomas. Oral Dis. 2002;8:100–105. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.2002.1c778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ochsenius G, Ortega A, Godoy L. et al. Odontogenic tumors in Chile: a study of 362 cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 2002;31:415–420. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2002.00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miki Y, Oda Y, Iwaya N. et al. Clinicopathological studies of odontoma in 47 patients. J Oral Sci. 1999;41:173–176. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.41.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu Y, Xuan M, Takata T. et al. Odontogenic tumors. A demographic study of 759 cases in a Chinese population. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;86:707–714. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90208-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mosqueda-Taylor A, Ledesma-Montes C, Caballero-Sandoval S. et al. Odontogenic tumors in Mexico: a collaborative retrospective study of 349 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;84:672–675. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90371-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacDonald-Jankowski DS. Odontomas in a Chinese population. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1996;25:186–192. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.25.4.9084271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Odukoya O. Odontogenic tumors: analysis of 289 Nigerian cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 1995;24:454–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1995.tb01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daley TD, Wysocki GP, Pringle GA. Relative incidence of odontogenic tumors and oral and jaw cysts in a Canadian population. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;77:276–280. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(94)90299-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Günhan O, Erseven G, Ruacan S. et al. Odontogenic tumours. A series of 409 cases. Austr Dent J. 1990;35:518–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1990.tb04683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaugars GE, Miller ME, Abbey LM. Odontomas. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;67:172–176. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(89)90324-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Grady JF, Radden BG, Reade PC. Odontomas in an Australian population. Aus Dent J. 1987;32:196–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1987.tb01854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Or Ş, Yücetas Ş. Compound and complex odontomas. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;16:596–599. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(87)80112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pizzirani C, Gemesio B. Clinical-statistical contribution to the study of odontoma. Dent Cadmos. 1984;52(6 Suppl):13. 15, 17 passim. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toretti EF, Miller AS, Peezick B. Odontomas: an analysis of 167 cases. J Pedod. 1984;8(3):282–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bodin I, Julin P, Thomsson M. Odontomas and their pathological sequels. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1983;12(2):109–114. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.1983.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Slootweg PJ. An analysis of the interrelationship of the mixed odontogenic tumors - ameloblastic fibroma, ameloblastic fibro-odontoma, and the odontomas. Oral Surg. 1981;51(3):266–276. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(81)90056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morning P. Impacted teeth in relation to Odontomas. Int J Oral Surg. 1980;9:81–91. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(80)80043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Regezi JA, Kerr DA, Courtney RM. Odontogenic tumors: analysis of 706 cases. J Oral Surg. 1978;36:771–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Budnick SD. Compound and complex odontomas. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1976;42:501–506. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(76)90297-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Santos JN, Pinto LP, de Figueredo CR. et al. Odontogenic tumors: analysis of 127 cases. Pesqui Odontol Bras. 2001;15:308–313. doi: 10.1590/s1517-74912001000400007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Happonen R-P, Ylipaavalniemi P, Calonius B. A survey of 15,758 oral biopsies in Finland. Proc Finn Dent Soc. 1982;78:201–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ogunsalu CO. Odontogenic tumours from two centres in Jamaica: A 15-year review. West Indian Med J. 2003;52:285–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu PC, Chan KW. A survey of tumours of the jawbones in Hong Kong Chinese: 1963-1982. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985;23:92–102. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(85)90058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bucci E, di Lauro F, Martina R. et al. Odontomas and their role in the etiopathogenesis of dental impaction. Clinical aspects, therapy and statistics. Minerva Stomatol. 1983;32(2):201–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nazargi Mahabob M, Anbuselvan GJ, Senthil Kumar B. et al. Prevalence rate of supernumerary teeth among non-syndromic South Indian population: an analysis. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2012;4(Suppl 2):S373–S375. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.100279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sharma A, Singh VP. Supernumerary Teeth in Indian children: a survey of 300 cases. Int J Dent. 2012;2012:1–5. doi: 10.1155/2012/745265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fardi A, Kondylidou-Sidira A, Bachour Z. et al. Incidence of impacted and supernumerary tetth - a radiographic study in a North Greek population. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2011;16(1):e56–e61. doi: 10.4317/medoral.16.e56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pippi R. A sixteen year sample of surgically treated supernumerary teeth. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2011;12:31–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vahid-Dastjerdi E, Borzabadi-Farahani A, Mahdian M. et al. Supernumerary teeth amongst Iranian orthodontic patients. A retrospective radiographic and clinical survey. Acta Odontol Scand. 2011;69:125–128. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2010.539979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schmuckli R, Lipowsky C, Peltomäki T. Prevalence and morphology of supernumerary teeth in the population of a Swiss Community. Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed. 2010;120:987–990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Enselik E, Özgür Sayin M, Onur Atilla A. et al. Supernumerary teeth in a Turkish population. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;136(6):848–852. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anthonappa RP, Omer RSM, King NM. Characteristics of 283 supernumerary teeth in southern Chinese children. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;105:e48–e54. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Oliveira Gomes C, Drummond SN, Jham BC. et al. A survey of 460 supernumerary teeth in Brazilian children and adolescents. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2008;18(2):98–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2007.00862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leco-Berrocal MI, Martín-Morales JF, Martinez-González JM. An observational study of the frequency of supernumerary teeth in a population of 2000 patients. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2007;12:134–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Harris EF, Clark LL. An epidemiological study of hyperdontia in American Blacks and Whites. Angle Orthodontist. 2008;78(3):460–465. doi: 10.2319/022807-104.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fernández Montenegro P, Valmaseda Castellón E, Berini Aytés L. et al. Retrospective study of 145 supernumerary teeth. Med Oral Pathol Oral Cir Bucal. 2006;11:339–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gábris K, Fábián G, Kaán M. et al. Prevalence of hypodontia and hyperdontia in paedodontic and orthodontic patients in Budapest. Community Dent Health. 2006;23:80–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Salcido-Garcia JF, Ledesma-Montes C, Hernandez-Flores F. et al. Frecuencia de dientes supernumarios en una poblacion Mexicana. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2004;9:403–409. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rajab LD, Hamdan MA. Supernumerary teeth: review of the literature and a survey of 152 cases. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2002;12:244–254. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.2002.00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miyoshi S, Tanaka S, Kunimatsu H. et al. An epidemiological study of supernumerary primary teeth in Japanese children: a review of racial differences in the prevalence. Oral Dis. 2000;6(2):99–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2000.tb00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Salem G. Prevalence of selected dental anomalies in Saudi children from Gizan region. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1989;17:162–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1989.tb00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Davis PJ. Hypodontia and hyperdontia of permanent teeth in Hong Kong school children. Ommunity Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1987;15:218–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1987.tb00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Luten JR. The prevalence of supernumerary teeth in primary and mixed dentition. J Dent Child. 1967;34:346–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pippi R, Sfasciotti C, Bazzarin S. Erupted odontoma: resolution of a case with tooth impaction. Doctor Os. 1994;5(7):40–48. (ita) [Google Scholar]

- 70.Al-Sahhar WF, Putrus ST. Erupted odontoma. Oral Surg. 1985;59:225–226. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(85)90023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gomel M, Seçkin T. An erupted odontoma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47:999–1000. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(89)90388-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dental care and dental health in Italy (Reference period: year 2005) Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT - December 9, 2008); http://www3.istat.it/salastampa/comunicati/non_calendario/20081209_00/ [Google Scholar]

- 73.Iatrou I, Vardas E, Theologie-Lygidakis N. et al. A retrospective analysis of the characteristics, treatment and follow-up of 26 odontomas in Greek children. J Oral Sci. 2010;25(3):439–447. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.52.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Al-Khateeb T, Al-Hadi Hamasha A, Almasri M. Oral and maxillofacial tumours in North Jordanian children and adolescents: a retrospective analysis over 10 years. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;32:78–83. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Servato JPS, de Souza PEA, Horta MCR. et al. Odontogenic tumours in children and adolescents: a collaborative study of 431 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;41:768–773. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2012.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sheehy EC, Odell EW, Al-Jaddir G. Odontomas in the primary dentition: literature review and case report. J Dent Child. 2004;71(1):73–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Butler PM. Studies of the mammalian dentition. Differentiation of the post-canine dentition. Proc Zool Soc Lond B. 1939;109:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Foster TD, Taylor GS. Characteristics of supernumerary teeth in the upper central incisor region. Dent Pract Dent Rec. 1969;20(1):8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sfasciotti M, Pippi R, Perfetti G. Denti sopranumerari e odontomi: analisi comparativa clinico-epidemiologica. Ann. Stomatol. 1991;40:61–79. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Howard RD. The unerupted incisor. A study of the postoperative eruptive history of incisors delayed in their eruption by supernumerary teeth. Dent Pract Dent Rec. 1967;17(9):332–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Takeda Y. Ameloblastic fibroma and related lesions: current pathologic concept. Oral Oncol. 1999;35:535–540. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(99)00039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Crivelini MM, Felipini CR, Miyahara GI. et al. Expression of odontogenic ameloblast-associated protein, amelotin, ameloblastin, and amelogenin in odontogenic tumors: immunohistochemical analysis and pathogenetic considerations. J Oral Pathol Med. 2012;41:272–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2011.01079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Crivelini MM, de Araújo VC, de Sousa SO. et al. Cytokeratins in epithelia of odontogenic neoplasms. Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2003;9:1–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.2003.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kiyoshima T, Nagata K, Wada H. et al. Immunohistochemical expression of thymosin β4 in ameloblastoma and odontomas. Histol Histopatol. 2013;28:775–786. doi: 10.14670/HH-28.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Piattelli A, Trisi P. Morphodifferentiation and histodifferentiation of the dental hard tissues in compound odontoma: a study of undemineralized material. J Oral Pathol Med. 1992;21:340–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1992.tb01361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Takata T, Zhao M, Uchida T. et al. Immunohistochemical detection and distribution of enamelysin (MMP-20) in human odontogenic tumors. J Dent Res. 2000;79:1608–1613. doi: 10.1177/00220345000790081401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Papagerakis P, Peuchmaur M, Hotton D. et al. Aberrant gene expression in epithelial cells of mixed odontogenic tumors. J Dent Res. 1999;78:20–30. doi: 10.1177/00220345990780010201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dodds AP, Cannon RE, Suggs CA. et al. mRNA expression and phenotype of odontogenic tumours in the v-HA-ras transgenic mouse. Arch Oral Biol. 2003;48(12):843–850. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(03)00178-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Łangowska-Adamcżyk H, Karmańska B. Similar locations of impacted and supernumerary teeth in monozygotic twins: a report of two cases. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2001;119:67–70. doi: 10.1067/mod.2001.111225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vadiati Saberi B, Shakoorpour A. Apert sindrome: report of a case with emphasis on oral manifestations. J Dent (Teheran) 2011;8(2):90–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Acevedo AC, da Fonseca JAC, Grinham J. et al. Autosomal-dominant ankyloglossia and tooth number anomalies. J Dent Res. 2010;89:128–132. doi: 10.1177/0022034509356401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lai MC1, King NM, Wong HM. Abnormalities of maxillary anterior teeth in Chinese children with cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2009 Jan;46(1):58–64. doi: 10.1597/07-077.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wu T-T, Chen PKT, Lo L-L. et al. The characteristics and distribution of dental anomalies in patient with cleft. Chang Gung Med J. 2011;34:306–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Schindel J, Kalmanovich M, Edlan A. et al. Cherubism. Int Surg. 1974;59(4):225–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ida M, Nakamura T, Utsunomiya J. Osteomatous changes and tooth abnormalities found in the jaws of patients with adenomatosis coli. Oral Surg. 1981;52(1):2–11. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(81)90164-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]