Abstract

Background

Various trials report improved outcomes for adolescents and young adults (AYA) with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) treated with pediatric- based regimens. This prompted the investigation of the pediatric Augmented Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster (ABFM) regimen in AYA patients. Results were compared with the hyper–fractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, Adriamycin and dexamethasone (hyper-CVAD) regimen in a similar population.

Methods

Eighty-five patients age 12 to 40 years with Philadelphia chromosome- (Ph) negative ALL were treated with ABFM from 10/2006 through 4/2012. Their outcome was compared to 71 historical AYA patients treated with hyper-CVAD from our institution. Patient and disease characteristics, as well as status of minimal residual disease (MRD), were analyzed for their impact on outcomes.

Results

The complete remission (CR) rate with ABFM was 94%. The 3-year complete remission duration (CRD) and overall survival (OS) rates were 70% and 74%, respectively. The 3-year CRD and OS were 72% and 85%, respectively, with age ≤ 21 years, and 69% and 60%, respectively, with age 21-40 years. Initial white blood cell count was an independent predictive factor of OS and CRD. The MRD status on Day 29 and Day 84 of therapy were also predictive of long-term outcomes. Severe regimen toxicities included transient hepatotoxicity in 35-39%, pancreatitis in 11%, osteonecrosis in 11%, and thrombosis in 22%. The 3-year OS rate was 74% with ABFM versus 71% with hyper-CVAD; the 3-year CRD rate was 70% with ABFM versus 66% with hyper-CVAD.

Conclusion

ABFM was tolerable in AYA patients with ALL but was not associated with significant improvements in CRD and OS compared with hyper-CVAD.

INTRODUCTION

In retrospective comparisons, the outcomes of adolescent and young adults (AYA) with acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) treated on pediatric protocols have been superior to outcomes of similar patients treated on adult protocols (1-4). An exception is Usvasalo, et al (5), which showed no difference in outcome between adult and pediatric-based treatment. Several studies have investigated pediatric-based regimens in adult ALL up to age 55 years (6-8). Older adults (age ≥ 40-45 years) had significantly worse toxicities with pediatric based regimens (7). Nachman and colleagues demonstrated that the ABFM regimen can be successfully administered to patients up to the age of 21 years, and was associated with a very favorable survival, particularly in patients with a rapid response to induction therapy (9). To improve the outcome of AYAs with ALL at our institution, ABFM therapy was investigated in newly-diagnosed patients ≤ 40 years with Ph-chromosome negative ALL. This regimen was chosen due to the success of ABFM therapy in patients 16-21 years old and its acceptable toxicity profile. Herein we report our results with ABFM and compare outcomes with hyper-CVAD in a similar historical AYA population.

METHODS

Study Group

Patients with Ph-negative ALL and age 12 to 30 years were initially enrolled. After evaluating toxicities in the first 10 patients, the upper age limit was expanded to 40 years. The diagnosis of ALL was confirmed by marrow morphology and flow cytometry. Other eligibility criteria included ECOG performance status of ≤ 3 and adequate renal and hepatic functions (unless the abnormalities were attributed to leukemia). Steroid treatment prior to enrollment was limited to 3 days initially, but this restriction was removed later. The protocol was approved by the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board, and informed consent for therapy was obtained according to the Declaration of Helsinki and our institutional guidelines.

Treatment

Treatment details are shown in Table 1 and have been previously published (10). Chemotherapy started within 72 hours of the first intrathecal chemotherapy. Bone marrow was re-assessed at Day 15. Patients with less than 5% marrow blasts by Day 15 were treated in the rapid responder group. They received one Consolidation 1 phase and one Consolidation 3A/3B phase of therapy. Slow responding patients received two Consolidations 1 phases and two Consolidations 3A/3B blocks of therapy. Patients with > 5% blasts in the marrow on Day 29 received two weeks of Extended Induction. At the end of the Extended Induction, patients with >5% marrow blasts were taken off study. Early responders received 12 intrathecal therapies (IT), while slow responders received 16 ITs. Patients with overt leukemia in the spinal fluid were treated with intensified ITs (see Table 1). Radiation for overt CNS leukemia was recommended.

Table 1.

Treatment

| Induction (4 weeks) |

| Daunorubicin 25 mg/m2 weekly × 4 doses |

| Vincristine 2 mg weekly × 4 doses |

| Prednisone 60 mg/m2/day by mouth for 28 days |

| PEG-asparaginase 2500 IU on day 4 of induction |

| Intrathecal cytarabine day 1 |

| Intrathecal methotrexate 12 mg on day 8 and day 29 |

| Consolidation 1 (8 weeks) |

| Cyclophosphamide 1 gram/m2 week 1 and week 5 |

| Cytarabine 75 mg/m2 SQ days 1-4 and 8-11 |

| Mercaptopurine 60 mg/m2/day by mouth days 1-14 |

| Vincristine 2 mg week 3 and week 4 |

| PEG-asparaginase 2500 IU week 3 and week 4 |

| Intrathecal methotrexate 12 mg weekly, weeks 1-4 |

| Consolidation 2 |

| Vincristine 2 mg every 10 days for 5 doses |

| Methotrexate IV every 10 days starting at 100 mg/m2 and increasing by 50 mg/m2 as tolerated |

| PEG-asparaginase 2500 IU weeks 1 and 4 |

| Intrathecal methotrexate 12 mg week 1 |

| Consolidation 3A |

| Doxorubicin 25 mg/m2 weekly × 3 doses |

| Dexamethasone 10 mg/m2 by mouth on days 1-7 and days 15-21 |

| Vincristine 2 mg IV weekly × 3 doses |

| PEG-asparaginase 2500 IU in week 1 |

| Intrathecal methotrexate 12 mg in week 1 |

| Consolidation 3B |

| Cyclophosphamide 1 gram/m2 week 1 |

| Cytarabine 75 mg/m2 SQ days 1-4 and days 8-11 |

| Thioguanine 60 mg/m2/day for 14 days |

| Intrathecal methotrexate 12 mg week 1 and 2 |

| Vincristine 2 mg weeks 3 and 4 |

| PEG-asparaginase 2500 IU week 3 |

| Maintenance (24 months) |

| Mercaptopurine 75 mg/m2 PO nightly |

| Methotrexate 20 mg/m2 PO weekly, hold on days of intrathecal methotrexate |

| Dexamethasone 6 mg/m2/day by mouth days 1-5 every 28 days |

| Vincristine 2 mg every 28 days |

| Intrathecal methotrexate 12 mg every 3 months for 4 doses |

| Slow responders repeat Consolidation 2 and Consolidation 3A/3B prior to maintenance |

| Testicular disease at diagnosis: if resolution by end of induction, then therapy continued. If abnormality persisted, then a biopsy was required and radiation administered if positive. |

| CNS disease at diagnosis: Intrathecal therapy given twice weekly until cleared, then weekly × 6 doses, then resume intrathecal treatments as per protocol. Radiation was recommended for overt CNS disease but was per investigator choice. |

Routine morphology and blast percentage in the marrow were assessed with Wright-Giemsa staining. Myeloperoxidase immunohistochemistry and four color flow cytometry (FCM) were performed. Rapid fluorescent in-situ hybridization (FISH) established preliminary Ph chromosome status using BCR-ABL probes. Rapid Ph chromosome testing was corroborated with conventional cytogenetics and PCR testing. Bone marrow morphology and minimal residual disease (MRD) were assessed on Day 29 and on approximately Day 84 of treatment. B-cell markers included CD9, CD10, CD13, CD15, CD19, CD20, CD22, CD34, and CD58 (sensitivity 10−4). MRD in the T-cell patients was followed using a panel of T-cell markers that included CD1, CD2, CD3 (surface and cytoplasmic), CD4, CD5, CD7, CD8 and CD 10. Standard cytogenetic studies were evaluated at diagnosis, and on Days 29 and 84 of therapy. PCR for t(12;21), BCR-ABL and MLL-rearrangements were performed at diagnosis (Asuragen LTX assay). Spinal fluid was assessed for malignant cells by cytopathology and Coulter counting. CNS disease status was defined as per pediatric ALL guidelines (11). During the course of the study, the PEG-asparaginase dose was capped at 3,750 units, which is the content of one vial. This was adopted due the expense of individual vials, and to avoid excessive toxicities from PEG-asparaginase.

Response Criteria and Toxicity

A complete response (CR) was defined as < 5% blasts in the bone marrow and normal peripheral blood counts. Induction death included all deaths prior to Day 29 of treatment (Day 42 if extended induction). Patients who had more than 5% blasts at Day 42 were removed from the study. Relapse was defined as recurrence of ALL at any site. Toxicities were defined by National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria, version 3.0.

Statistical Considerations

The endpoints of this single institution trial of ABFM therapy were CR, complete remission duration (CRD) and overall survival (OS). The CRD was measured from the date of CR until relapse. Differences in CR rates were analyzed by the chi squared or Fisher's exact tests. Unadjusted CRD and OS analyses were evaluated with Kaplan-Meier plots (12), and characteristics associated with differences in CRD and OS were assessed by log-rank testing (13). Cox proportional hazard regression (14) was used to evaluate factors predicting CRD and OS. Factors with a p-value ≤ .10 by univariate analysis were entered into the multivariate analysis. We found that MRD at Days 29 and 84 or greater were collinear and could not be included in the same model. Therefore, we constructed separate models to assess the effect of MRD at Days 29 and 84, separately. A p-value of <.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with IBM PASW Statistics 19 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois).

RESULTS

Patient Study Group

A total of 85 patients between the ages of 12 and 40 years with newly diagnosed Ph-negative ALL were treated with ABFM (Table 2). The median follow up is 40 months (range, 4 to 70 months). The ALL morphology was pre-B in 69 and T-cell in 16. The ECOG performance status was 2 in 9%; no patients had a performance status of ≥ 3. Forty percent of patients had a diploid karyotype. The karyotype was hyperdiploid in 20% of patients ≥ 21 years and in 18% of patients ≤ 21 years. Seven patients had CNS blasts at diagnosis on cytopathology review; only one patient had CNS 3. Three patients had Down Syndrome.

Table 2. Patient characteristics.

Patient characteristics at the time of enrollment and comparison to the historical patients treated with hyper-CVAD

| Augmented BFM | HCVAD | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 85 | 71 | |

| Male/Female | 49/36 | 42/29 | 0.85 |

| Median age in years (range) | 21 (13-39) | 26 (16-40) | <0.001 |

| No. with performance status 2 (%) | 8 (9) | 4 (6) | 0.38 |

| Median WBC at diagnosis (range) | 14 (0.4-494.2) | 6.7 (0.6-334.2) | 0.33 |

| No. with Pre-B Phenotype (%) | 69 (81) | 62 (87) | 0.30 |

| Blasts in blood (%), median (range) | 30 (0-93) | 28 (0-96) | 0.74 |

| No. karyotype with (%) | |||

| Diploid | 34 (40) | 30 (42) | |

| Hyperdiploid | 16 (19) | 15 (21) | |

| Hypodiploid | 9 (11) | 2 (3) | 0.44 |

| Pseudodiploid | 17 (20) | 12 (17) | |

| MLL | 3 (4) | 4 (6) | |

| ND/IM | 1/5 (1/6) | 0/8 (0/11) | |

| No. with CNS disease positive at diagnosis (%) | 7 (8) | 7 (10) | 0.73 |

| No. Transplanted in first CR (%) | 7 (8) | 6 (8) | 0.96 |

| Time period treated | 10/2006 - 4/2012 | 11/2002 - 9/2011 |

WBC, white blood cell count; MLL, mixed lineage leukemia gene rearrangement; ND, not done; IM, 1M=insufficient metaphases; CNS, central nervous system

Treatment Results

Overall, 80 of 85 patients (94%) achieved CR (Table 3). There was one induction death due to sepsis. One patient with trisomy 21 died of sepsis while in CR after completing induction, and one patient with Down Syndrome died of multi-organ failure, also secondary to sepsis, after completing consolidation 1.

Table 3. Treatment Response.

Response of patients to ABFM therapy.

| Overall | ≤21 | >21 | p-value (between 2 age groups) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number treated | 85 | 44 | 41 | |

| No. CR Overall (%) | 80 (94) | 43(98) | 37(90) | 0.14 |

| No. CR Day 29; (%) | 77(91) | 41(93) | 36(88) | 0.40 |

| No. D29 MRD-negative/positive | 46/26 | 25/12 | 21/14 | 0.50 |

| No. Day 84 MRD-negative/positive | 55/13 | 32/7 | 23/6 | 0.78 |

| No. Relapses | 25 | 16 | 9 | 0.14 |

| No. Deaths | 25 | 11 | 14 | 0.36 |

| No. Deaths in CR | 8 | 2 | 6 | 0.12 |

| No. Transplant in CR | 7 | 2 | 5 | |

| Alive after transplant | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| % CRD at 3yrs | 70 | 72 | 69 | 0.95 |

| MRD D29 negative/positive | 75/59 p=0.2 | 74/67 p=0.83 | 76/43 p=0.09 | 0.60/0.16 |

| MRD D84 negative/positive | 82/20 p=0.01 | 78/30 p=0.28 | 89/0 p=0.005 | 0.21/0.03 |

| % OS at 3yrs | 74 | 85 | 60 | 0.055 |

| MRD D29 negative/positive | 82/65 p=0.02 | 91/82 p=0.15 | 72/49 p=0.12 | 0.22/0.07 |

| MRD D84 negative/positive | 83/66 p=0.02 | 90/83 p=0.02 | 73/42 p=0.47 | 0.26/0.24 |

N-number; CR=complete response; D29 MRD=Day 29 minimal residual disease

Twenty-five patients have relapsed, and 14 of them have died. Eighteen of the relapsed patients were rapid early responders. Eight patients died in CR, four of them post-allogeneic SCT.

Seven patients underwent allogeneic stem cell transplantation in first morphologic CR, 2 of whom were 21 years or younger. Reasons for transplantation included slow clearance of minimal residual disease or high risk cytogenetic findings such as MLL gene rearrangement. Four of the 7 transplanted patients have died, two remain in CR, and one patient is alive with relapsed disease.

Rapid response by marrow morphology on Day 15 was 76%, 80% in patients ≤ 21 years and 73% in patients > 21 years (p=not significant). Isolated CNS relapse occurred in 6 (7%) patients; 3 patients(4%) have relapsed in the spinal fluid and the bone marrow. Sixteen (19%) patients had marrow relapse alone. The median time to relapse was 21.9 months in patients ≤ 21 years and 11.5 months in patients > 21 years.

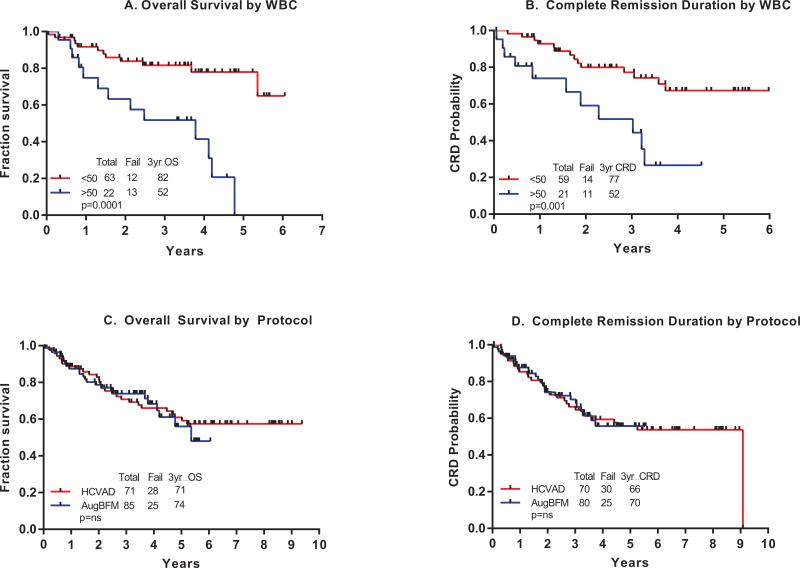

Remission Duration and Survival

Sixty (71%) patients remain alive with a median follow-up of 40 months (range 4-75 months). The 3-year OS and CRD rates were 74% and 70%, respectively the 3-year OS and CRD rates were 85% and 72%, respectively, for patients ≤ 21 years, and 60% and 69%, respectively, for patients > 21 years (Figure 1 A and B). The difference in the 3-year OS rates for the two age groups was borderline significant (p=0.055).

Figure 1A-1D.

Kaplan Meier curves of Overall Survival and Complete Remission Duration by age and day 29 minimal residual disease.

Outcome by MRD Status

The outcome of patients by MRD status is detailed in Table 3. The 3-year OS rate was 82% with a D29 MRD negative status versus 65% with MRD-positive status (Figure 1C; p=0.02). The 3-year CRD rate was 75% with a Day 29 MRD negative status versus 59% with MRD-positive status (Figure 1D; p=.2).

The 3-year OS rate was 83% with a Day 84 MRD-negative status versus 66% with MRD-positive status (p=0.02). The corresponding CRD rates were 82% versus 20% (p=0.01; Table 3). The results within age groups are shown in Table 3.

Prognostic Factors

On univariate analysis, the following factors were adverse for OS (p ≤0.10): D29 and D28 MRD positive status, leukocytosis > 50 x 109/L, older age (continuous variable; Figure 1A), and slow responder status. There were interactions between age and MRD status. On multivariate analysis, only leukocytosis (p ≤ .001) and Day 28 MRD-positive status (p=0.05) remained independently adversely associated with survival. In a second model, we included MRD status on Day 84, age, WBC at diagnosis, response type (rapid vs. slow), and cytogenetics (diploid vs. not diploid). Only WBC at diagnosis was independently associated with OS (p=.003).

On univariate analysis, the following factors were adverse for CRD (p ≤ 0.10): D84 MRD positive status and leukocytosis > 50 x 109/L (Figure 2B). On multivariate analysis, only leukocytosis remained independently adverse (p=0.04).

Figure 2A-2D.

Kaplan Meier curves of Overall Survival and Complete Remission Duration by presenting WBC and by protocol.

Comparison of ABFM and hyper-CVAD

The hyper-CVAD regimen details and results have been previously published (15). In this comparison, we included only patients ≤ 40 years old. Among such 71 patients, 37 (52%) had CD20-positive expression on leukemia cells ≥ 20% (median 77%; range 25-99%), and received rituximab 375mg/m2 for 8 doses in the first 4 induction-consolidation cycles.

Comparing ABFM with hyper-CVAD, there were no statistical differences in CR rates (CR rate 94% with ABFM versus CR in 70/71 patients on hyper-CVAD = 99%), or in CRD or OS rates between the two treatment regimens (Figures 2 C and D). The 3-year OS rate was 74% with ABFM versus 71% with hyper-CVAD; the 3-year CRD rate was 70% with ABFM versus 66% with hyper-CVAD. When OS and CRD were further analyzed in multivariate analyses including age, presenting WBC, and MRD status at the end of induction therapy, no statistically significant differences in outcome were detected by treatment regimen (data not shown).

Regimen toxicities

Toxicities associated with the ABFM regimen, particularly hepatic toxicity, were significant but expected (Table 4). Grade 3-4 hyperbilirubinemia was observed in 39%, and grade 3-4 liver enzyme elevations in 35%. Liver toxicity resolved in most patients, but resulted in chemotherapy dose decrements and omissions per protocol guidelines. Hypofibrinogenemia was prominent (36%), but did not result in excessive bleeding. Thrombosis, mostly in the upper extremities where central lines were located, occurred in 22%; stroke-like events developed in 3 patients. Toxicities that led to permanent changes in therapy consisted of osteonecrosis (11%), severe allergy to PEG-asparaginase (21%) and pancreatitis (11%). The incidence of osteonecrosis is comparable to the incidence seen in adolescents treated on pediatric trials (10). A higher incidence of severe asparaginase allergy was noted on study than in the pediatric literature (16)Neuropathy was not prominent; only 4 patients had vincristine held due to grade 3 neuropathy. Infections and febrile episodes during induction and later in therapy were common and did not significantly differ between the age groups. Fever or documented infections were noted in 22% of patients during induction, and in 63% during consolidations.

Table 4.

Toxicities overall and by age.

| No. (Percent) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Toxicity | Overall (n=85) | Age ≤ 21 years (n=44) | Age > 21 years (n=41) |

| Allergic reaction, asparaginase | 18(21) | 9(20) | 9(22) |

| Grade 3-4 hypofibrinogenemia | 31 (36) | 10(23) | 21(51) |

| Pancreatitis | 9(11) | 4(9) | 5(12) |

| Grade 3-4 elevated liver enzymes | 30(35) | 12(27) | 18(44) |

| Grade 3-4 elevated bilirubin | 33(39) | 17(39) | 16(39) |

| Osteonecrosis | 9(11) | 6(14) | 3(7) |

| Thrombosis | 19(22) | 8(18) | 11(27) |

| Stroke-like event | 3(4) | 1(2) | 2(5) |

| neuropathy Grade 3-4 | 4(5) | 2 (4) | 2 (5) |

• P-values not significant by age group, except for hypofibringogenemia (p=.006)

DISCUSSION

In this experience in newly diagnosed AYA patients with ALL, the ABFM regimen resulted in a CR rate of 94%, a 3-year OS rate of 74%, and a CRD rate of 70%. Severe toxicities of the regimen were significant but expected, and mostly related to PEG-asparaginase based therapy: hepatotoxicity in 35-39%, pancreatitis in 11%, osteonecrosis in 11%, and thrombotic events in 22%.

The results of this trial were retrospectively compared to the historical data with Hyper-CVAD regimen in a similar population at our institution, in relation to CR, OS, and CRD. The two populations, those treated with ABFM and those treated with Hyper CVAD were well matched (Table 2). The patients treated with Hyper CVAD, while all being between age 16 and 40, were older, with a median age of 26 years (p<0.001). Presenting WBC, performance status, and blast phenotype were not statistically different between the two groups. Despite the higher age in the Hyper CVAD group, a known adverse prognostic factor in ALL, the efficacy results were similar with ABFM and hyper-CVAD, but the toxicity profiles were different: asparaginase-related with ABFM, myelosuppression with HCVAD. It is thus reasonable to extrapolate that other “adult ALL” regimens were inferior to “pediatric” regimens because they may have mimicked more adult AML-like regimens: reliance on allogeneic and autologous stem cell transplantation in first CR, less consolidations and shorter maintenance durations, and less intrathecal chemotherapy. The hyper-CVAD regimen maintained the core principles of the pediatric ALL regimens but reduced reliance of asparaginase (17). Therefore, the current shift to pediatric-based therapy for AYA patients with ALL, especially those ≥ 21 years, may need further assessment.

A high WBC at presentation remained an independent predictor of OS in multivariate analysis. Historically, T-cell ALL patients may present with high WBC and yet may have acceptable OS (18). The T-cell ALL group in our study was too small to analyze the relative importance of morphology and WBC count. However, AYA patients with pre-B ALL and leukocytosis should be considered for additional intensifications (e.g. allogeneic stem cell transplantation) or novel strategies (e.g. new monoclonal antibodies).

Molecular or flow cytometry studies measuring MRD have strongly predicted for relapse in pediatric ALL studies (19-25). In AYAs with ALL, MRD status at the end of induction therapy has also been associated with survival differences (26,27). In our study, a negative MRD status by multicolor flow cytometry on Day 29 and Day 84 was associated with improved survival (Table 3). A similar effect of MRD on prognosis was noted with the hyper- CVAD regimen (15). Thus, patients with MRD positivity in CR may be considered for allogeneic stem cell transplant or for novel therapies while in first morphologic CR (28). Concerns over toxicities of pediatric-based therapies are legitimate, and mostly asparaginase-related: hepatotoxicity (35-39%), pancreatitis (11%), osteonecrosis (11%), thrombosis (22%). Infectious complications during prolonged steroid administration may be problematic. Infectious death during induction occurred in one patient, a death rate comparable to other studies in children and in adults during ALL therapy (29,30). There were 8 deaths in CR, two of the deaths were patients with Down Syndrome, and four were after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. All patients were given anti-bacterial and anti-fungal prophylaxis during periods of severe neutropenia. Avascular necrosis appears to be less prominent in AYA up to age 40 than in teen-age patients (31,32). Hypofibrinogenemia, while frequent, did not cause bleeding. Thrombosis was higher than reported in pediatric patients (33), and most thrombi were related to central lines.

The rate of CNS relapse was similar to published pediatric and adult studies, yet the number of intrathecal treatments was less than in prior pediatric trials of ABFM (9). Intrathecal therapy has side-effects such as impaired cognitive function, seizures and white matter damage. Decreased intrathecal treatments might be feasible and beneficial to AYA patients in future treatment regimens.

Adherence to therapy may limit the effectiveness of the chemotherapy (34,35). Non-compliance may be related to the age group or to the complexity and length of the treatments. Several AYAs (n=10; 12%) withdrew from treatment. Older adults on even simpler regimens for leukemia still have issues with compliance (36), and AYA patients may be even less compliant (37). Breaks in therapy due to toxicities also occurred. Such deviations in therapy undermine cure rates in children with ALL (38). One in five patients had severe allergic reactions to PEG-asparaginase. Decreases in planned doses of asparaginase result in decreased event-free survival (39). In this study, patients switched to Erwinia asparaginase after severe allergic reactions to PEG-asparaginase, a strategy that has resulted in effective asparagine depletion in patients with allergic reactions to E.coli asparaginase (40). Approximately 10% of patients on this study developed pancreatitis, an incidence similar to that in children (41). These patients did not receive further asparaginase.

In summary, AYA patients with ALL treated with ABFM had high OS and CRD rates, and tolerated this pediatric regimen with acceptable toxicity. OS and CRD rates were comparable to those obtained with hyper-CVAD, an adult leukemia regimen.

Acknowledgments

This article was supported by National Institute of Health ( P30 CA016672 ).

Research Support: None

Footnotes

AUTHORSHIP

Contribution: M.E.R. and H.M.K. conceived the idea, designed the study protocol, analyzed data, contributed patients and wrote the manuscript. D.A.T., S.M.O., F.R-K., E.J.J., A.R.F., T.M.K., N.P., N.G.D., A.F., G.G-M., M.Y.K., J.E.C., G.B., S.M.K. contributed patients and analyzed data. K.S. performed assessments. R.G. and M.C-T. performed statistical analysis. J.L.J. performed immunophenotype analysis. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

DISCLOSURE OF CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stock W, La M, Bloomfield CD, et al. What determines the outcomes for adolescents and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated on cooperative group protocols? Blood. 2008;112(5):1646. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-130237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boissel N, Auclerc MF, Lheritier V, et al. Should adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia be treated as old children of young adults? Comparison of the French FRALLE-93 and LALA-94 trials. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(5):774. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramanujachar R, Richards S, Hans I, et al. Adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: outcome on UK national paediatric (ALL97) and adult (UKALLXII/E2993) trials. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(3):254. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ram R, Wolach O, Vidal L, et al. Addolescents and young adults with acute luymphoblastic leukemia have a better outcome when treated with pediatric-inspired regimens: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Hematol. 2012 May;87(5):472–8. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Usvasalo A, Raty R, Knuutila S, et al. Acute lymphoblastic Leukemia in adolescents and young adults in Finland. Haematologica. 93(8):1161–8. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ribera J, Oriol A, Sanz MA, et al. Comparison of the results of the treatment of adolescents and young adults with standard-risk ALL. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(11):1843. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.7265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huguet F, Leguay T, Raffoux E, et al. Pediatric-inspired therapy in adults with Philadelphia chromosome-negative ALL. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(6):911. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.6916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lukenbill J, Advani A. The treatment of adolescents and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Curr Hematol Malig Reports. 2013;8(2):9197. doi: 10.1007/s11899-013-0159-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nachman J, La MK, Hunger SP, et al. Young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia have an excellent outcome with chemotherapy alone and benefit from intensive postinduction treatment: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(311):5189. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seibel N, Steinherz PG, Sather SN, et al. Early postinduction intensification therapy improves survival for children and adolescents with high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Blood. 2008;111(5):2548. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-070342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pui C, Howard S. Current management and challenges of malignant disease in the CNS in paediatric leukaemia. Lancet Oncol. 2008 Mar;9(3):257–68. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaplan EL, et al. Non-parametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1965;53:457. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mantel N. Evaluation of survival data and two new rank order statistics arising in its consideration. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1966;50(3):163–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. J R Stat Soc. 1972;34:187. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas D, O'Brien S, Faderl S, et al. Chemoimmunotherapy With a Modified Hyper-CVAD and Rituximab Regimen Improves Outcome in De Novo Philadelphia Chromosome-Negative Precursor B-Lineage Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2014;28(24):3880–89. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.9456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurtsberg J, Asselin B, Bernstein M, et al. Ployethylene Glycol-conjugated L-asparaginase versus native L-asparaginase in combination with standard agents for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in second bone marrow relapse: a Children's Oncology Group Study (POG 8866). J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011 Dec;33(8):610–616. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31822d4d4e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kantarjian H, Thomas D, O'Brien S, et al. Long-term follow-up results of hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (Hyper-CVAD), a dose-intensive regimen, in adult acute lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 2004;101(12):2788–801. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pullen J, Shuster J, Link M, et al. Significance of commonly used prognostic factors differs for children with T cell acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL), as compared to those with B-precursor ALL. A Pediatric Oncology Group (POG) study. Leukemia. 1999 Nov;13(11):1696–707. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Dongen JJ, Seriu T, Panzer-Grumayer ER, et al. Prognostic value of minimal residual disease in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in childhood. Lancet. 1998;352(9142):1731. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)04058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacquy C, Delepaut B, Van Daele S, et al. A prospective study of minimal residual disease in childhood B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Hematol. 1997;98(1):140. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.1792996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conter V, Bartram CR, Valsecchi MG, et al. Molecular response to treatment redefines all prognostic factors in children and adolescents with B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115(16):3206. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-248146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borowitz M, Devidas M, Hunger SP, et al. Clinical significance of minimal residual disease in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and its relationship to other prognostic factors: A Children's Oncology Group Study. Blood. 2008;111(12):5477. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-132837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dworzak MN, Froschl G, Printz D, et al. Prognostic significance and modalities of flow cytometric minimal residual disease detection in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2002;99(6):1952–8. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Basso G, Veltroni M, Valsecchi MG, et al. Risk of relapse of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia is predicted by flow cytometric measurement of residual disease on day 15 bone marrow. J Clin Oncol. 2002;27(31):5168–74. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coustan-Smith E, Sancho J, Hancock ML, et al. Clinical importance of minimal residual disease in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2000;96(8):2691–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bassan R, Spinalli O, Oldani E, et al. Improved risk classification for risk-specific therapy based on the molecular study of minimal residual disease (MRD) in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Blood. 2009 Apr 30;113(18):4153–62. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-185132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagafuji K, Mayamoto T, Eto T, et al. Monitoring of minimal residual disease (MRD) is useful to predict prognosis of adult patients with Ph-negative ALL: results of a prospective study (ALL MRD 2002 Study). J Hematol Oncol. 2013 Feb. 6(6):14. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-6-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gokbuget N, Kneba M, Raff T, et al. Adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and molecular failure display a poor prognosis and are candidates for stem cell transplantation and targeted therapies. Blood. 2012 Aug 30;120(9):1868–76. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-377713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prucker C, Attarbaschi A, Peters C, et al. Induction death and treatment related mortality in first remission of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2009;23(7):1264–9. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rubnitz J, Lensing S, Zhou Y, et al. Death during induction therapy and first remission of acute leukemia in childhood. Cancer. 2004;101(7):1677–84. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mattano LA, Sather H, Trigg M, et al. Osteonecrosis as a complication of treating acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children: a report from the Children's Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol. 2000 Sep 15;18(18):3262. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.18.3262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.te Winkel ML, Pieters R, Hop WC, et al. Prospective study on incidence, risk factors, and long-term outcome of osteonecrosis in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(31):4143–50. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.3217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nowak-Gottl U, Ahlke I, Fleischhack G, et al. Thromboembolic events in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BFM protocols): prednisone versus dexamethasone administration. Blood. 2003 Apr 1;101(7):2529–33. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lancaster D, Lennard L, Lilleyman J. Profile of non-compliance in lymphoblastic leukaemia. Arch Dis Child. 76 doi: 10.1136/adc.76.4.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pritchard MT, Butow P, Stevens M, et al. Understanding medication adherence in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a review. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2006 Dec;28(12):816–23. doi: 10.1097/01.mph.0000243666.79303.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marin D, Bazeos A, Mahon FX, et al. Adherence is the critical factor for achieving molecular responses in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia who achieve complete cytogenetic responses on imatinib. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(14):2381–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Festas RS, Tamaroff MH, Chasalow F, et al. Therapeutic adherence to oral medication regimens by adolescents with cancer. I. Laboratory assessment. J Pediatr. 1992;120(5):807–11. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80256-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhatia S, landier W, Shangguan M, et al. Nonadherence to oral mercaptopurine and risk of relapse in Hispanic and non-Hispanic white children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the childrens's oncology group. J Clin Oncol. 2012 Jun 10;30(17):2094–101. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.9924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barry E, DeAngelo DA, Neuberg D, et al. Favorable outcome for adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated on Dana-Farber Cancer Institute acute lymphoblastic leukemia consortium protocols. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(7):813–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.6397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Panosyan E, Seibel NL, Martin-Aragon S, et al. Asparaginase antibody and asparaginase activity in children with higher-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia: children's cancer group study CCG-1961. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2004;26(4):217–26. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200404000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raja R, Schmiegelow K, Frandsen T. Asparaginase-associated pancreatitis in children. Br J Haematol. 2012;159:18–27. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]