Abstract

Males and females show a different predisposition to certain types of seizures in clinical studies. Animal studies have provided growing evidence for sexual dimorphism of certain brain regions, including those that control seizures. Seizures are modulated by networks involving subcortical structures, including thalamus, reticular formation nuclei, and structures belonging to the basal ganglia. In animal models, the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNR) is the best studied of these areas, given its relevant role in the expression and control of seizures throughout development in the rat. Studies with bilateral infusions of the GABAA receptor agonist muscimol have identified distinct roles of the anterior or posterior rat SNR in flurothyl seizure control, that follow sex-specific maturational patterns during development. These studies indicate that (a) the regional functional compartmentalization of the SNR appears only after the third week of life, (b) only the male SNR exhibits muscimol-sensitive proconvulsant effects which, in older animals, is confined to the posterior SNR, and (c) the expression of the muscimol-sensitive anticonvulsant effects become apparent earlier in females than in males. The first three postnatal days are crucial in determining the expression of the muscimol-sensitive proconvulsant effects of the immature male SNR, depending on the gonadal hormone setting. Activation of the androgen receptors during this early period seems to be important for the formation of this proconvulsant SNR region. We describe molecular/anatomical candidates underlying these age- and sex-related differences, as derived from in vitro and in vivo experiments, as well as by [14C]2-deoxyglucose autoradiography. These involve sex-specific patterns in the developmental changes in the structure or physiology or GABAA receptors or of other subcortical structures (e.g., locus coeruleus, hippocampus) that may affect the function of seizure-controlling networks.

Keywords: Substantia nigra pars reticulata, GABA receptor, Dimorphism, Androgen receptor, Estrogen receptor, Critical period, KCC2, Rat, Immature, Locus Coeruleus, Hippocampus, Seizures, Epilepsy

Introduction

Various subcortical structures play a critical role in modulating seizures. A great deal of data has been provided concerning a role for thalamus, especially in models of primary generalized epilepsy (see the review by Avanzini et al., 2000), and several structures belonging to the basal ganglia–cortical circuits have been extensively studied. Among them a pivotal role in seizure modulation seems to be played by the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNR) as well as the superior colliculus (SC) and subthalamic nucleus (STN) through their connections with the SNR (Garant and Gale, 1987; Lado et al., 2003; Velísková et al., 1996a). There is also evidence concerning the role of monoaminergic subcortical nuclei, and in particular for the noradrenergic (NE) locus coeruleus (LC), and the serotonergic (5HT) raphe nuclei. These structures are part of the brainstem reticular formation, are formed by neurons whose axons widely inner-vate the cortical mantle, such as the noradrenergic axons, and exert a modulatory role on their targets.

In the last two decades, it has been clearly shown that the SNR has significant sex-related effects on different types of seizures, and that some of these vary significantly during development. Most of the present review will primarily address the sex-specific features of the SNR, including its differentiation, morphology and function in seizure control, and will discuss potential mechanisms and implications of such a dimorphism. Lastly, we will also address the existing evidence for a potential dimorphic role of other seizure-controlling structures.

The SNR: a predominantly GABAergic basal ganglia nucleus

The SNR constitutes the main part of substantia nigra (SN). The SNR is formed almost exclusively of fast-spiking GABAergic cells (Gerfen, 2004; Schultz, 1986), which are much less densely packed than their dopaminergic counterpart of the pars compacta of the SN (SNpc). A few dopaminergic cells can also be found in the posterior SNR (SNRp) (González-Hernández and Rodríguez, 2000). The SNR together with the globus pallidus internal (GPi), which in rodents is represented by the entopeduncular nucleus, is the main output structure of the basal ganglia.

SNR neurons receive afferents from the STN, lateral globus pallidus (GP) and from the striatum. They send axon terminals to structures outside of the basal ganglia, namely the thalamus, the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus (PPT) and the SC (Gerfen, 2004); in addition, each GABAergic SNR neuron sends axon collaterals to neighboring SNR neurons (Deniau et al., 1982; Grofova et al., 1982). Specific subregions of the SNR receive projections from specific subregions of the afferent nuclei, and such a topographical segregation is maintained also in the targets of SNR efferents (reviewed in Gerfen, 2004), The thalamic targets of SNR include bilateral projections to the ventromedial (VM), parafascicular, centromedian and paracentral nuclei and unilateral projections to the centrolateral, mediodorsal and thalamic reticular nucleus (Gulcebi et al., 2012).

Communication via GABAA receptors (GABAAR) helps orchestrate the net activity of SNR neurons, although other neurotransmitter systems such as glutamatergic receptors play a role too (Zhou and Lee, 2011). GABAARs are pentameric ligand-activated ionic channels permeable to chloride ions and, to a lesser extent, to bicarbonate (Farrant and Kaila, 2007; Galanopoulou, 2008b). The precise composition of GABAARs in terms of subunits types determines their kinetics, affinity to drugs, sub-cellular localization (extra- or post-synaptic), or region-specific expression in a complex manner (Galanopoulou, 2008b; Mohler, 2006). Usually, functional channels comprise two α and two β subunits. When the fifth subunit is a δ subunit, GABAAR are extrasynaptic and responsible for tonic current generation. In contrast, GABAAR with a γ subunit are most commonly post-synaptic, generating phasic inhibitory post-synaptic currents (IPSCs), but can also be found at extrasynaptic sites (reviewed in Galanopoulou, 2008b).

GABAAR signaling classically induces neuronal hyperpolarization, due to an influx of Cl−, which follows the electrochemical Cl− gradient between the extracellular and the intracellular compartments. The intracellular Cl− concentration ([Cl−]i) is regulated by cation Cl− cotransporters. These include Cl− exporters, like K+/Cl− cotransporters (KCCs), and Cl− importers like the Na+/K+/Cl− cotransporters (NKCCs). During development, there is a gradual shift in the expression and activity of two main representatives, mainly NKCC1 which declines (Plotkin et al., 1997) and KCC2 that increases with age (Rivera et al., 1999). As a result, the [Cl−]i is considerably higher in most studied immature neurons compared to the mature ones. Thus, activation of GABAARs in immature neurons with high [Cl−]i triggers depolarizing potentials due to the efflux of Cl− and hyperpolarizing potentials in mature neurons with low [Cl−]i, due to Cl− influx. The early depolarizing GABAAR signaling is essential for normal brain development, as it results in depolarization-induced activation of L-type voltage-sensitive calcium channels (L-VSCCs) and NMDA receptors (reviewed in (Ben-Ari, 2002; Farrant and Kaila, 2007; Galanopoulou, 2008b). In fact, precocious termination of the depolarizing GABA effects may have serious adverse effects in the way normal neurons develop and arborize to form synaptic connections (Cancedda et al., 2007; Wang and Kriegstein, 2008, 2011). It is worth noting that in the normal brain the GABAAR-mediated depolarizations are not necessarily excitatory, as they can still induce a weaker form of inhibition, shunting inhibition, when neuronal depolarization exceeds the reversal potential of GABAARs (Staley and Mody, 1992).

The role of SNR in seizure control in males

In the early 1980s, it was shown that in male adult rats, microinfusions of muscimol (a GABAAR agonist) in the SNR exert anticonvulsant effects toward different types of experimental seizures such as tonic hindlimb extension in the maximal electroshock test and tonic and clonic seizures produced by pentylenetetrazole and bicuculline (Iadarola and Gale, 1982), as well as toward flurothyl-induced clonic seizures (Okada et al., 1986), a seizure model which allows a precise quantification of the seizure threshold. [14C]2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) auto-radiographic studies showed that the SNR was differently involved in kainic acid-induced seizures in adult male rats versus male rat pups (Albala et al., 1984) and, surprisingly, that bilateral muscimol microinfusions into the SNR of 15-17 postnatal days (PN) old male rat pups were proconvulsant in flurothyl-induced clonic seizures (Garant et al., 1995; Moshé and Albala, 1984; Okada et al., 1986; Sperber et al., 1987). The age-related differences in the modulation of the nigral output systems following various pharmacological manipulations were documented in several studies summarized in Table 1 and point out that there is an age-related role of the SNR in the control of seizures but also in motor control. Indeed, given the known higher propensity of the immature CNS to seizures and status epilepticus (Moshé and Albala, 1983; Moshé et al., 1983), the SNR has been considered as an important candidate to justify such an age-related shift in seizure susceptibility and expression that may be involved in human seizures too.

Table 1.

Early data on the developmental effects of bilateral SNR infusions of GABAergic or glutamatergic agents toward flurothyl-induced seizures in male rats.

| Chemical | Mechanism | PN15 male SNR | Adult male SNRa | Adult male SNRp | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muscimol | GABAAR agonist (low-/high-affinity site) | Proconvulsant | Anticonvulsant | Proconvulsant | Moshé et al., 1983,1994; Velísková and Moshé, 2001 |

| THIP | GABAAR agonist | Biphasic effects | Anticonvulsant | Not tested | Garant et al., 1995; Xu et al., 1992 |

| GVG | Inhibitor of GABA aminotransferase | Anticonvulsant | Anticonvulsant | Proconvulsant | Xu et al., 1991a,b |

| Velísková et al., 1996b | |||||

| Bicuculline | GABAAR antagonist (low-affinity site) | Proconvulsant | Proconvulsant | No effect | Sperber et al., 1987 Velisková et al., 1996b |

| ZAPA | GABAAR agonist (low-/high-affinity site) | Biphasic effects | Anticonvulsant | Proconvulsant | Sperber et al., 1999 Velisková et al., 1996b |

| Zolpidem | GABAAR agonist (al selective agonist) | Anticonvulsant | Anticonvulsant | No effect | Velísková et al., 1998b |

| Baclofen | GABABR agonist | Anticonvulsant | No effect | Not tested | Sperber et al., 1989a,b |

| CGP 35,348 | GABABR antagonist | Proconvulsant | No effect | Not tested | Velísková et al., 1994 |

| AP7 | NMDA receptor antagonist | No effect | Anticonvulsant | Proconvulsant | Wurpel et al., 1992 |

Modified from Scantlebury et al., 2009. Biphasic effects indicate anticonvulsant effect with low doses and proconvulsant with high doses Abbreviations: GVG: γ-vinyl-GABA; SNR: substantia nigra pars reticulata; SNRa: anterior part of substantia nigra pars reticulata; SNRp: posterior part of substantia nigra pars reticulata; PN15: postnatal day15; THIP: 4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo[5,4-c]pyridin-3-ol; ZAPA: (Z)-3-[(aminoiminomethyl)thio]prop-2-enoic acid; AP7: DL-2-amino-7-phosphonoheptanoic acid.

In parallel with the growing amount of data on the role of SNR on seizures, another important observation was made in the mid-90s. Detailed analysis on the effects of the spatial features relating the microinfusions of pharmacologic agents into specific regions of SNR along its anterior–posterior axis led to the discovery that actually the SNR of adult male rats can be divided into two functionally separate regions, an anterior (SNRa) and a posterior one (SNRp), bearing different effects in the flurothyl-induced clonic seizures (Moshé et al., 1994; Sperber et al., 1999; Velísková et al., 1996b; Velísková and Moshé, 2001). In particular, in adult male rats, bilateral muscimol infusions are anticonvulsant if infused in the SNRa and proconvulsant if infused in the SNRp (Sperber et al., 1999). Region-specific effects were also noted for the GABAAR agonist (Z)-3-[(aminoiminomethyl)thio] 2-propenoic acid (ZAPA) and γ-vinyl-GABA which increases local GABA levels (Velísková et al., 1996b). In contrast, bicuculline (a GABAAR antagonist) infusions were proconvulsant into the SNRa and without any effect in the SNRp (Velísková et al., 1996b) (see also Table 1).

A remarkable observation was that in male rat pups, up to PN21 (see also below), such a regional differentiation was not present, and muscimol microinfusions were always proconvulsant, irrespective of the site of SNR infusion (Moshé et al., 1994; Sperber et al., 1999; Velísková and Moshé, 2001).

In vivo evidence for a gender-related effect of SNR toward seizures

For almost two decades since the discovery of a prominent role of SNR in seizure susceptibility, all of the above-mentioned studies, either in adult or immature rats, were performed in males, as it is usually done in rodent research. The biasing role of such aspect became clear only many years later, when the role of sex was analyzed for the first time. Such studies, together with an in-depth analysis of the interaction of sex with brain development, provided unexpected results.

The first studies in which the role of sex was analyzed were performed by Moshé's group using bilateral muscimol infusions either in the SNRa or SNRp. It was shown that although muscimol infusions in the SNRa had anticonvulsant effects in both male and female adult rats, there was a clear sex difference when muscimol was infused in the SNRp, eliciting proconvulsant effects in males and having no effect in females (Moshé, 1997; Velísková and Moshé, 2001). In fact, a detailed developmental study on the effects of bilateral muscimol infusions in flurothyl seizure control revealed the following.

(a) The functional differentiation between the SNRa and SNRp in seizure control starts to appear after PN21, in both sexes, but the effects of muscimol are sex-specific in PN15–21: proconvulsant in PN15-21 males, without effect in PN15–21 females.

(b) The muscimol-sensitive proconvulsant SNR region is present in males only. It is present irrespective of SNR region between PN15–21 and only by the SNRp infusions in older male rats.

(c) The muscimol-sensitive anticonvulsant SNR region is localized to the SNRa, in both sexes, but emerges earlier in females (≥PN25) than in males (≥PN30).

The role of sex hormones in the development of SNR sex dimorphic effects on seizures

Sex hormones have a key role in orchestrating sexual dimorphic features (for review, see Shah et al., 2012). During brain development, sex hormones have organizational effects which induce permanent anatomical differences between males and females in specific brain structures (McEwen, 1999). In early development, the levels of testosterone (T) are critical for the formation of male or female phenotypic features of the brain that eventually will be expressed in adulthood (McEwen, 1999). T can affect brain development, either a) through the action of T or its metabolite dihydrotestosterone (DHT) on androgen receptors (AR) or, b) through the action of the aromatase-mediated metabolite 17β-estradiol (E) on estrogen receptors (ER) (McEwen et al., 1982; McEwen and Parsons, 1982).

Most of these dimorphic effects are linked to the perinatal surge in T levels in males (Arnold and Gorski, 1984), which occurs around gestational days 18–19 (Ward and Weisz, 1984; Weisz and Ward, 1980) and during the first few hours following birth (Baum et al., 1988; Corbier et al., 1978; Slob et al., 1980). Regional differences in hormonal levels have been found across brain regions and these may be even higher in sexually dimorphic structures (Konkle and McCarthy, 2011). In fact, there is a so-called “critical period” during which sex hormones exert their organizational effects in many brain structures and in rats the first 6 days of life are considered particularly critical for the effects of T and its metabolites (Goy and McEwen, 1980). The levels of gonadal hormones in the brain are not however only defined by the peripherally circulating hormones but also by the local steroidogenesis in certain brain regions and the metabolism of existing steroids. For example, the levels of E at birth vary significantly across brain regions, suggesting region-specific levels of local estradiol synthesis in the brain (Konkle and McCarthy, 2011). Furthermore, in the hippocampus or hypothalamus, the local steroid levels (T, DHT, E) are not affected by neonatal (PN0) adrenal-ectomy or gonadectomy, suggesting that local steroidogenesis in these regions utilizes substrates different than the peripherally circulating T (Konkle and McCarthy, 2011). In fact, the idea that only T can serve as substrate for E production has been contested, and the possibility that other C19 steroids can also be converted to E has been proposed (Lieberman, 2008).

Concerning the role of SNR on seizures, Velísková and Moshé (2001) showed that postnatal T is responsible for the male proconvulsant phenotype of SNR muscimol effects on flurothyl seizures . They showed that: a) castration of males at PN0 produces the female-like responses of SNR muscimol on clonic flurothyl-induced seizures at PN15 (i.e., lack of any effect on seizures); since this change did not occur in sham operated males a causative role for perinatal stress could be ruled out (Velísková and Moshé, 2001); b) daily administration of T from PN0 to PN14 to either females or to PN0-castrated males induces the appearance of the SNR proconvulsant phenotype, a characteristic of intact males (Velísková and Moshé, 2001).

Subsequent studies investigated which T metabolite (i.e., DHT or E) was responsible for this maturational effect, and which was the precise duration of this critical period (Giorgi et al., 2007). The data showed that: (a) PN0-2 seems to be the “gonadal hormone sensitive period” for the formation of the muscimol-sensitive proconvulsant phenotype of the male SNR and (b) both estrogenic [diethylstilbestrol (DES)] and androgenic [T or DHT] compounds given between PN0 and PN2 either in females or in PN0-castrated males, can induce the appearance of the muscimol-sensitive proconvulsant SNR function. A further series of experiments, by Heida et al. (2008) strengthened this scenario, by showing that, in males, the early postnatal (PN0–2) systemic administration of flutamide (an AR antagonist) is sufficient to lead to the disappearance of the proconvulsant muscimol effects at P15. The latter observation was somehow unexpected, since it had been previously observed that the masculinization of the brain is mainly mediated by the action of estrogen (reviewed in Shah et al., 2012), while an exclusive role of androgens has been considered for a long time to be implicated in few brain structures, and especially in the spinal cord (i.e. nucleus bulbocavernosus (Breedlove et al., 1982)). However, there are complex interactions between the AR and ER responsive pathways that could further complicate these interpretations. For instance, perinatal flutamide administration has been shown to increase the ovarian production of E in pigs, by enhancing aromatization (Grzesiak et al, 2012). Indeed, a shared effect of androgens and estrogens seems to be relevant for some masculinizing effects (Breedlove, 1997; Han and De Vries, 2003; Shughrue and Dorsa, 1994).

Thus, activation of both AR and ER appears to be important for the presence of proconvulsant SNR muscimol responses. Interestingly, a relevant role of androgens for the sexual differentiation in the brain, has been observed in other brain regions such as amygdala, hippocampus, hypothalamus, and LC (Garcia-Falgueras et al., 2005; Jones and Watson, 2005; Morris et al., 2005), as witnessed by studies using male rats with testicular feminization mutation. The effects of early sex hormone manipulations on the SNR have been tested also in terms of the gonadal hormone receptor expression. In particular, Ravizza et al. (2003a) analyzed the gonadal receptor expression in the rat SNR at PN1, and found that, while SNR expression of ERα is similar in the two sexes, female rats showed a higher AR and ERβ immunoreactivity (-ir) compared with males. Females treated with T at PN1 had lower levels of both AR and ERβ than controls. Interestingly, the number of AR- and ER-expressing cells was not affected by this treatment. Even though these data do not allow to extrapolate precise functional effects, they suggest that the hormonal receptor expression itself in the SNR differs in males and females, is dependent on the early postnatal hormonal setting, and might self-perpetuate a structural/functional maturation of SNR in a sex-specific manner.

Evidence for sexual dimorphism of the GABAAR expression in the rat SNR

The molecular basis for the differences of SNR response in vivo and in vitro (see below) to GABAergic agents is still under investigation. The GABAAR subunit composition is a potential candidate, given its role in the functional effects of GABA (reviewed in Galanopoulou, 2008b; Olsen and Sieghart, 2009) (Table 2). Thus, it has been shown by in-situ hybridization, that the distribution of α1 and γ2 GABAAR subunit positive cells was homogeneous across the SNRa and SNRp in PN15 male rats. However, in PN21 and older animals, the SNRa appeared to be less densely populated by α1- or γ2-positive cells, but individually stained SNRa cells contained more silver grains than those in the SNRp (Velísková et al., 1998a). Similar regional differences were reported for the α1 mRNA expression in the female SNR (Ravizza et al., 2003b). Furthermore, when comparing males and females, within each SNR region, expression of α1 subunit mRNA was always higher in females compared to age-matched males (Ravizza et al., 2003b).

Table 2.

GABAergic in vivo and in vitro parameters in SNR cells in relation to sex and developmental stage.

| SNR parameter | Age sex | Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| GABA-ir cells/section | PN15, PN30 | Males < females | Ravizza et al., 2003 a |

| Males–females | SNRa < SNRp (all groups except PN30 males) | ||

| Density of GABA-ir/cell | PN15, PN30 | Males < females | Ravizza et al., 2003 a |

| Males–females | PN15: SNRa = SNRp; PN30: SNRa > SNRp | ||

| GABAaR α1 mRNA/cell | PN15, PN30 | males < females | Ravizza et al., 2003a |

| Males–females | PN15: SNRa = SNRp; PN30: SNRa > SNRp | ||

| PN15–adults | SNRa < SNRp in adults, SNRa = SNRp at PN15 | Moshé et al., 1994 | |

| Males | |||

| PN15–PN21–PN60 | PN15: SNRa = SNRp; PN21: SNRa > SNRp | Velísková et al., 1998a | |

| Males | |||

| GABAAR α1 mRNA ex pressing cells | PN15, PN21, PN60 | PN15: SNRa = SNRp; PN21 and PN60: SNRa < SNRp | Velísková et al., 1998a |

| Males | Moshé etal., 1994 | ||

| Density of GABAAR α1-ir/SNRa cell | PN5, PN15, PN30 | PN5: males < females; | Chudomel et al., 2009 |

| Males–females | PN15 < PN30 (both sexes) | ||

| Density of GABAaR α3-ir/SNRa cell | PN5, PN15, PN30 | PN5: males < females, PN5 > PN15 > PN30; | Chudomel et al., 2009 |

| Males–females; SNRa | males: PN5, PN15 > PN30; females: PN5 > PN15 > PN30 | ||

| only | |||

| GABAAR γ2L mRNA/cell | PN15, PN21, PN60 | PN15: SNRa = SNRp; | Velísková et al., 1998a |

| Males | PN21, PN60: SNRa > SNRp | ||

| GABAAR γ 2 L subunit expressing | PN15, PN21, PN60 | PN15:SNRa = SNRp; | Velísková et al., 1998a |

| cells | Males | PN21, PN60: SNRa < SNRp | |

| KCC2 mRNA | PN15, PN30, adults | PN15, PN30: males < females | Galanopoulou etal. |

| Males–females | Males: PN15 < PN30 < adult; females: PN15 < PN30 | 2003 | |

| PN15: SNRa = SNRp atPN15; PN30, adult: SNRa > SNRp | |||

| GABAergic cells neurogenesis | BrdU: E13–14–15; | GABAergic cell density: males < females | Galanopoulou etal. |

| Tested at PN30; | Earlier peak of neurogenesis of SNRa (≤E13) than SNRp (E13–14) | 2001 | |

| Males-females | Earlier peak ofneurogenesis offemales | ||

| Spontaneous IPSCs | PN5–9; PN12–15; | IPSCs frequency, amplitude, charge transfer: increase with age; | Chudomel et al., 2009 |

| PN28–32 | |||

| Males–females | IPSC rise and decay times: decrease with age; | ||

| PN5–9: males have higher IPSC frequencies, amplitudes, and charge transfers than PN5-9 | |||

| females; | |||

| PN28–32 males have | |||

| Higher IPSC amplitudes, and shorter rise/decay times than PN28–32 females; | |||

| α 1 GABAAR-mediated IPSCs | PN5–9; PN12–15; | Zolpidem-induced increase in decay time increases with age. | Chudomel et al., 2009 |

| PN28–32 | |||

| Males–females | Zolpidem-induced increase in charge/IPSCs is lower in PN5–9 males than the rest of groups. |

Abbreviations: BrdU: bromo-deoxy-uridine; DES: diethylstilbestrol; DHT: 5α-dihydrotestosterone; GABAA R: GABAAR; ir: immunoreactive; PN: postnatal day; SNRa: anterior part of substantia nigra pars reticulata; IPSCs: inhibitory post-synaptic currents.

In 2009, Chudomel et al. reported the protein expression of α1 and α3 subunits in the SNRa of PN5-30 male and female rats, using immunochemistry and compared it with the developmental changes in the kinetics of GABAAR-IPSCs. A developmental increase in perisomatic α1-ir and decrease in α3-ir was observed in both males and females, between PN5 and PN30 (Table 2). This developmental swap of α3 by α1 subunits is well known to occur in several brain regions, affecting the kinetics and drug sensitivity of GABAAR-IPSCs (Chudomel et al., 2009; Gingrich et al., 1995; Lavoie et al., 1997; Verdoorn, 1994). Indeed, in whole cell patch clamp experiments, the kinetics of IPSCs became faster with age and more responsive to the α1-preferring agonist zolpidem, consistent with the increase in α1-ir (Chudomel et al., 2009). The only sex differences observed were a higher expression of α1-ir and α3-ir in female PN5 SNRa paralleled by a greater sensitivity of female PN5-9 SNRa neurons to zolpidem, compared with same age males.

A pattern similar to the one above described for the α1 subunit applies for the content of GABA within PN15 and PN30 SNR neurons (Ravizza et al., 2003b): this is lower, in general, in males than in same age females, and is also higher in SNRa than in SNRp neurons of PN30 rats (Ravizza et al., 2003b) (see Table 2).

Earlier appearance of hyperpolarizing GABAAR signaling in female SNR: is it relevant to its muscimol-sensitive anticonvulsant function?

To investigate whether the sexually dimorphic function of the SNR involved sex differences in the physiology of local SNR neurons, Galanopoulou et al. (2003) studied the electrophysiological properties of GABAARs of PN14-17 SNR GABAergic neurons using gramicidin perfo-rated patch clamp recordings, which preserve the [Cl−]i (Kyrozis and Reichling, 1995). Bath application of muscimol depolarized GABAergic SNR neurons from male pups, while it hyperpolarized female SNR neurons (Galanopoulou et al., 2003). In parallel, fura2AM imaging of SNR GABAergic neurons demonstrated that muscimol bath application induced an increase in [Ca++]i in male SNR neurons, but not in female SNR neurons. These observations altogether were exciting since they seemed to show that single cell SNR phenomena could underlie at least in part a complex sex-related difference occurring in vivo (i.e. the modulatory role of GABA SNR manipulation toward seizures), which is likely to involve several structures apart from SNR itself. By using the same experimental protocol, it was also demonstrated that in the SNRa the switch of GABAAR-mediated postsynaptic currents occurs around PN17 in males and around PN10 in females (Kyrozis et al., 2006).

Additional studies demonstrated that GABAAR agonists such as muscimol can only activate the transcription of calcium-sensitive genes, like KCC2, or increase the phosphorylation of the transcription factor cAMP responsive element binding protein at Ser133 (pCREB) in PN15 male but not in PN15 female SNR neurons (Galanopoulou et al., 2003; Galanopoulou, 2006), confirming that this sexual dimorphism in GABAAR signaling has broader repercussions on gene transcription and potentially in neuronal differentiation and sexual differentiation of the SNR.

Sex hormones may influence the mRNA expression of KCC2 in PN15 male and female SNR (Galanopoulou and Moshé, 2003). Administration of 17β-E reduced KCC2 mRNA expression in only PN15 male SNR neurons and this effect occurred in the presence of GABAAR depolarization-induced L-VSCC activation. In contrast, T or DHT increased KCC2 mRNA expression in PN15 rat SNR, regardless of the direction of GABAAR signaling. These observations suggest that the higher perinatal E levels in males could suppress KCC2 gene expression, delaying the developmental increase of KCC2 and appearance of hyperpolarizing GABAAR signaling. Although the local levels of E in the neonatal male SNR have not been measured, it is possible that the local aromatization of the elevated circulated T in males could result into more estrogenic derivatives.

Neonatal hormonal manipulations that feminized the function of the PN15 SNR in seizure control were also capable of switching the responses of GABAARs in PN13-16 SNR neurons (Table 3) (Giorgi et al., 2007). Castration of neonatal male rats rendered GABAARs in PN13-16 SNR neurons hyperpolarizing, as in females, regardless of the age the castration was performed (PN0 or PN3). Furthermore, early hormonal administration (DES or DHT) between PN0 PN2, in PN0-castrated males or intact females, was not sufficient for the depolarizing GABAAR responses characteristic of PN13–16 SNR neurons to emerge. Parallel studies showed that more prolonged daily exposure to E (PN0–4 but not PN0–2) was needed to reduce KCC2 mRNA expression and permit the depolarizing GABAA receptor responses to appear in the PN15 SNR (Galanopoulou, unpublished data) (Galanopoulou, 2008a).

Table 3 GABAAR in vivo and in vitro responses of SNRa neurons in relation to sex, developmental stage and early gonadal hormone manipulation.

| Group | Effects of muscimol infusion in SNRa on flurothyl-induced seizures in vivo | GABAAR responses of SNRa neurons in vitro |

|---|---|---|

| PN15 males | ||

| Intact | Proconvulsant | Depolarization |

| PN0-castrated | No effect | Hyperpolarization |

| PN0-castrated + TP (PN0-2) | Proconvulsant | Hyperpolarization |

| PN0-castrated + DES (PN0-2) | Proconvulsant | |

| PN0-castrated + DHT (PN0-2) | Proconvulsant | |

| PN15 females | ||

| Intact | No effect | Hyperpolarization |

| TP (PN0-15) | Proconvulsant | |

| TP (PN0-2) | Proconvulsant | Hyperpolarization |

| DES(PN0-2) | Proconvulsant | Hyperpolarization |

| DHT (PN0-2) | Proconvulsant | Hyperpolarization |

| PN21 males | Proconvulsant | Hyperpolarization |

| PN21 females | No effect | Hyperpolarization |

| PN30 males | Anticonvulsant | |

| PN30 females | Anticonvulsant |

Abbreviations: DES: diethylstilbestrol; DHT: 5α-dihydrotestosterone; GABAAR: GABAA receptor; PN: postnatal day; SNRa: anterior part of substantia nigra pars reticulata; TP: testosterone propionate.

The above findings suggest that, in PN15 male SNR, the muscimol-sensitive proconvulsant function is not directly mediated by the depolarizing GABAAR signaling of SNR neurons. In further support is the observation that the disappearance of the muscimol-sensitive proconvulsant SNRa role occurs after PN21 (Velísková and Moshé, 2001), while the depolarizing GABAAR responses of SNRa neurons disappear by PN17 (Kyrozis et al, 2006). However, these observations cannot exclude that the presence of depolarizing GABA during the neonatal period, could promote the differentiation of the muscimol-sensitive proconvulsant SNR region, through activation of downstream cascades of calcium-sensitive signaling processes. Indeed, as will be described in the subsequent review (Akman et al., in this issue), insults that cause precocious termination of depolarizing GABAARs in the male SNR can abolish the proconvulsant function of the PN15 male SNR.

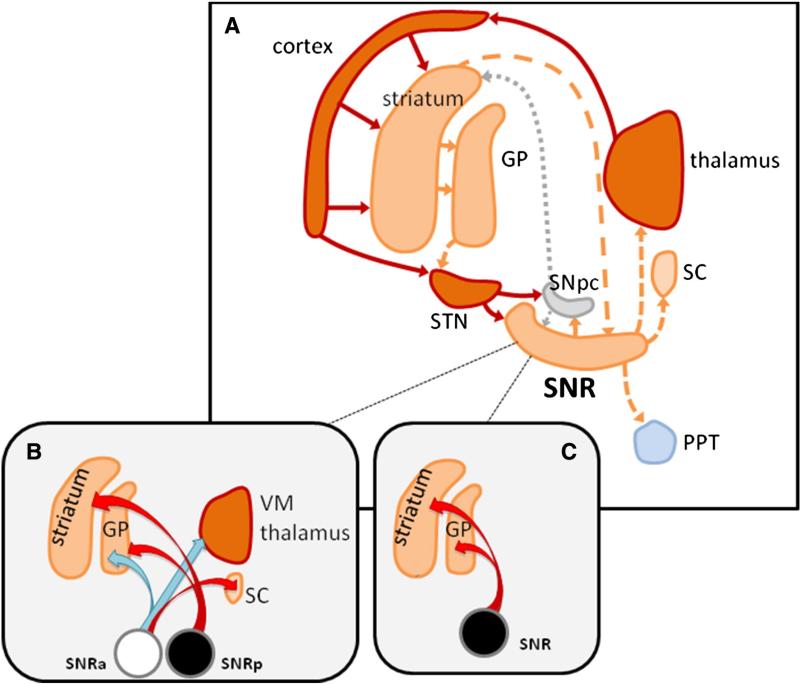

Sex differences in SNR-related output connections as a function of age

The SNR is part of a larger network that includes the primary seizure focus – when such a focus can be identified – regions controlling seizure onset or propagation (“gateways”), as well as seizure termination (Avanzini et al., 2012; Gale, 1992; Lado and Moshé, 2008; Velísková and Moshé, 2006). Several lines of evidence have demonstrated that components of the basal ganglia, including the SNR, as well as other interacting brain regions (e.g., thalamus, cortical regions or brainstem nuclei) can modulate the susceptibility to and propagation of seizures. The SNR is connected with the remaining basal ganglia structures, receiving input mainly from the striatum and STN, and projecting towards the SC and VM thalamus, the parafascicular, centromedian and paracentral nuclei, but also to the centrolateral, mediodorsal and thalamic reticular nucleus (Gulcebi et al., 2012) thus affecting, indirectly, many telencephalic structures (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of connections of male SNR in relation with seizure modulation. A: The SNR receives GABAergic afferents from the GP, as well as from the striatum; it also receives direct dopaminergic afferents from the SNpc, and glutamatergic projections from the STN. SNR, together with the globus pallidus internal (not shown in the figure) is the only output structure from the basal ganglia. It sends GABAergic efferents to its target structures: the thalamus, the SC and PPT. All of these three structures play a crucial role in seizure modulation. The cortex, thalamus and STN mainly send glutamatergic projections to their targets (dark red solid arrows); SNR, striatum and GP send GABAergic inhibitory efferents to their targets (orange dashed arrow); dotted gray arrows represent SNpc dopaminergic efferents. The PPT is formed by cholinergic neurons. Panels B and C show the effects of unilateral infusions of muscimol in the male SNR in terms of increased (red arrows) or decreased (blue arrows) [14C]2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) uptake in target regions (from Moshé et al., 1994, and unpublished observations from Moshé's Lab). The SNR sites are schematized as circles: the SNRa with an anticonvulsant effect of muscimol is depicted in white, while the proconvulsant site is in black. B: In adult male rats, unilateral muscimol infusion in the SNRp (where bilateral muscimol infusions are proconvulsant) increases 2-DG uptake in the ipsilateral GP and striatum; unilateral muscimol infusion into the SNRa (where bilateral muscimol infusions are anticonvulsant) decreases 2-DG uptake in the ipsilateral VM and GP, while it increases 2-DG uptake in the ipsilateral SC. C: in PN15 male rat SNR (where bilateral intranigral muscimol infusions are proconvulsant), unilateral muscimol infusions increase 2-DG uptake in the ipsilateral GP and striatum. Abbreviations: GP: lateral globus pallidus; PPT: pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus; SC: superior colliculus; SNpc: pars compacta of the substantia nigra; SNR: pars reticulata of the substantia nigra; SNRa: anterior part of SNR; SNRp: posterior part of SNR; STN: subthalamic nucleus; VM: ventro-medial thalamic nucleus.

It is likely that the age- and sex- specific differences in the way individual network components mature may impact the way and timing when different regions become connected or respond to each other. As a result, the functional output of a network may follow age- and sex-specific maturation patterns that are distinct from those of its individual components.

To delineate the structures that are affected by muscimol intranigral infusions, 2-DG autoradiography studies were performed. Moshé et al. (1994) injected 2-DG 30 min after unilateral muscimol infusions, a timepoint that corresponds to the time when muscimol-infused rats are exposed to flurothyl. It was demonstrated that in adult male rats, muscimol infusions into the SNRa induced specific regional metabolic changes depending on the infusion site. While infusions into the SNRa are associated with decreased glucose utilization into the ipsilateral striatum, the sensorimotor cortex and VM, infusions into the SNRp do not affect the sensorimotor cortex and increase glucose uptake at the level in the ipsilateral GP, and in the dorsal striatum (Moshé et al., 1994). These data suggest that this network could be important in mediating the proconvulsant effect of muscimol infusions into the SNRp. The timing between administration of muscimol infusions and 2-DG is crucial in demonstrating these networks (Velísek et al., 2005).

The components of a network are not exclusively utilized for a single function and within each region there may be region-specific functional specifications, which may follow different age and sex specific patterns of maturation. Furthermore, the context within which a network operates (e.g., under normal conditions or in the presence of a chemoconvulsant) may change its final output. For example, unilateral muscimol infusions in the SNR of normal rats can elicit circling behavior towards the contralateral side (Moshé et al., 1994; Velísek et al., 2005). However, in this experimental paradigm, muscimol had sex-specific effects on circling frequency when infused in the SNRa of adult male and female rats, but not when infused in the SNRp. This is quite different from the effects of intranigral muscimol on flurothyl seizure control, where sex differences are observed with the infusions in the SNRp but not in the SNRa.

Are there other subcortical seizure controlling structures which are sexually dimorphic?

Other sites involved in seizure phenomenology and onset have sex-related features, and among them one cannot forget the amygdala (see, for instance, Cooke and Woolley, 2005; Stefanova and Ovtscharoff, 2000). The list of potential candidates apart from SNR involves several areas (for reviews, see for instance Galanopoulou, 2008a; Gale, 1992; Lado and Moshé, 2008), including the hippocampus (Galanopoulou, 2008b), thalamic structures (which can be especially relevant in generalized and in limbic epilepsies), as well as serotonergic and noradrenergic nuclei giving rise to a more diffuse effect through a widespread innervations of the brain (Jacobs and Azmitia, 1992; Szabadi, 2013). In the hippocampus, female CA1 pyramidal neurons begin manifesting hyperpolarizing GABAAR responses to physiological synaptic stimulation much earlier than males (i.e., already at PN4 versus PN14 in males) (Akman et al., in this issue; Galanopoulou, 2008a,c), and this correlates with the higher expression of KCC2 and decreased activity of NKCC1-like, bumetanide-sensitive, cation chloride cotransporters in females (Galanopoulou, 2008a,c).

5HT may have a relevant role in models of epilepsy and, likely, in human epilepsy (Dailey et al., 1992; Jobe, 2003). There is a report showing a higher content for 5HT and its metabolites in the hypothalamus of female rats compared to male rats; however, this may be transient and not sufficient to produce changes in postsynaptic 5-HT receptors (Ferrari et al., 1999). To date, no data exist on sex differences in 5HT innervations of cortical regions, which are likely to be an important site for the effects of 5HT on seizures (Jobe, 2003).

The hypothalamus seems to be involved in subcortical spreading of different types of seizures (Mirski and Fisher, 1994; Shehab et al., 1992; Silveira et al., 2000), as well as to play a role as a seizure-triggering area in some patients and typically those affected by hypothalamic hamartomas (Pati et al., 2013). Thus, sex-related differences in this area might be relevant for epilepsy sex-related differences as well. In line with this, it is worth noting that many studies have shown that there are clear sex-related differences in GABAergic parameters in rats. For instance, hypothalamic GABA content and turnover are higher in males than females (Frankfurt et al., 1984; Searles et al., 2000), the expression of KCC2 is lower in neonatal males vs females, while the opposite occurs for NKCC1 (Perrot-Sinal et al., 2007), and neonatal hypothalamic muscimol infusions increase pCREB in males while decreasing it in females (Auger et al., 2001).

There are interesting hints for potential dimorphic features of the LC in seizure modulation. LC sends direct projections to the whole cortex (either archi-, paleo- or neocortex), as well as to several sub-cortical structures and it is the main source for norepinephrine (NE) in the brain, and especially for limbic structures (Fallon et al., 1978; Giorgi et al., 2003), where it is considered to exert modulatory effects which might be relevant for mood, emotions and stress responses (Aston-Jones et al., 1996; Itoi and Sugimoto, 2010). Concerning seizures, a pivotal role for LC has been confirmed for all of the models of limbic seizures tested so far, including amygdala kindling (McIntyre, 1980; McIntyre and Edson, 1981), seizures evoked focally from the piriform cortex (Giorgi et al., 2003, 2006, 2008), or by systemic chemoconvulsants (Szot et al., 1999). Furthermore, LC plays also a crucial role in extralimbic seizure models, including pentylenetetrazol and maximal electroshock-induced seizures (Mason and Corcoran, 1978, 1979; Mishra et al., 1994), as well as spontaneous seizures occurring in GEPR-3 and 9 rats (Jobe et al., 1994).

LC exhibits sex-related features. In females, LC neurons possess a dendritic tree with longer and more branched processes, giving rise also to a denser and wider innervation (extending also to peri-LC region) (Bangasser et al., 2011), and receive a denser and probably more “efficient” input from different afferent structures, especially limbic ones (Bangasser et al., 2011). Electrophysiological studies have shown that corticotropin-releasing factor, a neuropeptide cotransmitter of LC afferents from limbic structures, exerts a higher activating effect on female than in male LC neurons (Curtis et al., 2006). The above quoted dimorphic features are permanent and due to early dimorphic differentiation, since sex-hormonal manipulation in adult rats does not affect them (Bangasser et al., 2011; Curtis et al., 2006), even though there are no specific data on the extent of the critical period responsible for this sexual dimorphism. Even though these aspects have been interpreted as crucial in the proposed different role of emotional stimuli in affecting arousal in women vs. men, with an emphasis on gender-related differences of stress-related psychiatric disorders (Bangasser and Valentino, 2012), they might have implications for epileptogenesis too. To delineate whether there are dimorphic differences in the role of LC in seizures, it should be assessed whether there is a difference in NE release in crucial sites during seizures, in males versus females, since an increased release of NE in limbic structures has been observed during seizures, and might have self-inhibitory effects (Giorgi et al., 2003). Furthermore, it should also be assessed whether the LC produces different effects in different seizures models in males and females.

Concluding remarks

There is emerging evidence that gender differences may be important in the etiology and expression of epilepsy in humans (Perucca et al, this issue; van Luijtelaar et al, this issue). The pathophysiological basis for the sex-related differences is still far from being understood, but the dimorphism of seizure-controlling structures might have a role. Thus far, the SNR is the only seizure-modulating structure for which the sexually dimorphic functional role on seizures (i.e. the anti-or proconvulsant effects of GABAergic SNR infusions) have been clearly established and confirmed. Most of the available data on the role of sex in SNR effects have been obtained in rats, in the flurothyl clonic–tonic model, since it allows a precise quantification of the seizure threshold. It would be interesting to assess its sex and age-dependent role in other animal models of seizures too, in which SNR has been shown to play an important role in male adult rats [e.g., amygdala kindling (Löscher et al., 1987), maximal electroshock model (Iadarola and Gale, 1982)]. In rats, it is now known that there is a critical postnatal period during which the gonadal hormones and their various metabolites determine the sex- and age-related maturation of the GABAergic system and seizure-controlling function of the SNR. These findings also suggest the importance of testing for possible age- and sex-related differences in the effects of systemically administered GABAergic drugs in seizures (see Akman et al, in this issue). However, the net result of systemic GABAergic drug administration cannot be predicted, because the same drug may affect various brain regions with different – and even opposite – effects toward seizures. This has been, for example, shown with the muscimol infusions in the SC versus SNR (Gale, 1992). The potential occurrence of age- and/or sex-related differences in the effects of GABAergic drugs should be investigated in detail in other subcortical structures as well. In the clinical setting, rigorous comparison of the effect of GABAergic drug in the two sexes, at different ages, and in specific epilepsy syndromes (e.g. focal symptomatic, generalized symptomatic, or genetic epilepsies) may disclose potentially relevant differences which, at least in part, could be related to the degree of age- and sex- related involvement of SNR in these syndromes.

Recently, the loop diuretic drug bumetanide (a blocker of NKCC1) has been evaluated for its potential anticonvulsant effect, in models of neonatal seizures (e.g. Dzhala et al., 2008; Cleary et al., 2013; Mazarati et al., 2009) and in one patient (Kahle et al., 2009). As mentioned above, NKCC1 has an age-dependent expression in SNR and hippocampus. While the effects of bumetanide on seizures need to be interpreted cautiously (Vanhatalo et al., 2009; Chabwine and Vanden Eijnden, 2011), it would be worth testing also the effects of loop diuretic drugs into the SNR to assess their potential age- and sex-related role in SNR-mediated epilepsy modulation.

The potential dimorphic effects of other powerful seizure-modulating systems/nuclei, and involving neurotransmitters other than GABA, deserve further investigations, too. The noradrenergic nucleus LC is a strong potential candidate, and even in this case disclosing such differences might help understanding the male/female and age-dependent differences in the susceptibility to seizures, as well as to design specific treatments tailored according to personalized features of the patients.

Acknowledgments

ASG acknowledges research grant funding from: NINDS (NS078333), CURE, Autism Speaks, Department of Defense, and the Heffer Family and Siegel Family Foundations. ASG has received royalties from Morgan & Claypool Publishers and John Libbey Eurotext Ltd, and consultancy honorarium from Viropharma. SLM received grants from NINDS (NS020253, NS043209, NS045911, NS078333), Department of Defense, CURE, the Heffer Family and Siegel Family Foundations, and consultancy honorarium from Lundbeck and UCB Pharma. FSG has no current funding to disclose.

Abbreviations

- AR

androgen receptors

- DES

diethylstilbestrol

- 2-DG

[14C]2-deoxyglucose

- DHT

dihydrotestosterone

- E

17β-estradiol

- ER

estrogen receptors

- GABAAR

GABAA receptors

- GP

lateral globus pallidus

- KCC

K+/Cl− cotransporter

- IPSC

inhibitory post-synaptic current

- -ir

immunoreactivity

- LC

locus coeruleus

- L-VSCC

L-type voltage sensitive calcium channel

- NE

norepinephrine

- NKCC

Na+/K+/Cl− cotransporter

- PN

postnatal day

- PPT

pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus

- SC

superior colliculus

- SNpc

pars compacta of the substantia nigra

- SNR

pars reticulata of the substantia nigra

- SNRa

anterior part of SNR

- SNRp

posterior part of SNR

- STN

subthalamic nucleus

- T

testosterone

- VM

ventromedial thalamic nucleus

References

- Akman O, Moshé SL, Galanopoulou AS. Sex-specific consequences of early life seizures. Neurobiology of Disease. Special Issue Sex and Epileptogenesis. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.05.021. (in this issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albala BJ, Moshé SL, Okada R. Kainic-acid-induced seizures: a developmental study. Brain Res. 1984;315:139–148. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(84)90085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold AP, Gorski RA. Gonadal steroid induction of structural sex differences in the central nervous system. Ann. Rev. Neurosci. 1984;7:413–442. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.07.030184.002213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Rajkowski J, Kubiak P, Valentino RJ, Shipley MT. Role of the locus coeruleus in emotional activation. Prog. Brain Res. 1996;107:379–402. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)61877-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auger AP, Perrot-Sina TS, McCarthy MM. Excitatory versus inhibitory GABA as a divergence point in steroid-mediated sexual differentiation of the brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:8059–8064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131016298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avanzini G, Panzica F, de Curtis M. The role of the thalamus in vigilance and epileptogenic mechanisms. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2000;111(Suppl. 2):S19–S26. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(00)00398-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avanzini G, Manganotti P, Meletti S, Moshé SL, Panzica F, Wolf P, Capovilla G. The system epilepsies: a pathophysiological hypothesis. Epilepsia. 2012;53:771–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangasser DA, Zhang X, Garachh V, Hanhauser E, Valentino RJ. Sexual dimorphism in locus coeruleus dendritic morphology: a structural basis for sex differences in emotional arousal. Physiol. Behav. 2011;103:342–351. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangasser DA, Valentino RJ. Sex differences in molecular and cellular substrates of stress. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2012;32:709–723. doi: 10.1007/s10571-012-9824-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum MJ, Brand T, Ooms M, Vreeburg JT, Slob AK. Immediate postnatal rise in whole body, content in male rats: correlation with increased testicular content and reduced body clearance of testosterone. Biol. Reprod. 1988;38:980–986. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod38.5.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y. Excitatory actions of GABA during development: the nature of the nurture. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002;3:728–739. doi: 10.1038/nrn920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breedlove SM, Jacobson CD, Gorski RA, Arnold AP. Masculinization of the female rat spinal cord following a single injection of testosterone propionate but not estradiol benzoate. Brain Res. 1982;237:173–181. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90565-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breedlove SM. Neonatal androgen and estrogen treatments masculinize the size of motoneurons in the rat spinal nucleus of the bulbocavernosus. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 1997;17:687–697. doi: 10.1023/A:1022590104697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancedda L, Fiumelli H, Chen K, Poo MM. Excitatory GABA action is essential for morphological maturation of cortical neurons in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:5224–5235. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5169-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabwine JN, Vanden Eijnden S. A claim for caution in the use of promising bumetanide to treat neonatal seizures. J. Child Neurol. 2011;26:657–658. doi: 10.1177/0883073811401395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chudomel O, Herman H, Nair K, Moshé SL, Galanopoulou AS. Age- and gender-related differences in GABAA receptor-mediated postsynaptic currents in GABAergic neurons of the substantia nigra reticulata in the rat. Neuroscience. 2009;163:155–167. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary RT, Sun H, Huynh T, Manning SM, Li Y, Rotenberg A, Talos DM, Kahle KT, Jackson M, Rakhade SN, Berry G, Jensen FE. Bumetanide enhances phenobarbital efficacy in a rat model of hypoxic neonatal seizures. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057148. (doi: 10. 1371) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke BM, Woolley CS. Sexually dimorphic synaptic organization of the medial amygdala. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:10759–10767. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2919-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbier P, Kerdelhue B, Picon R, Roffi J. Changes in testicular weight and serum gonadotropin and testosterone levels before, during, and after birth in the perinatal rat. Endocrinology. 1978;103:1985–1991. doi: 10.1210/endo-103-6-1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis AL, Bethea T, Valentino RJ. Sexually dimorphic responses of the brain norepinephrine system to stress and corticotropin-releasing factor. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:544–554. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailey JW, Mishra PK, Ko KH, Penny JE, Jobe PC. Serotonergic abnormalities in the central n, ervous system of seizure-naïve genetically epilepsy-prone rats. Life Sci. 1992;50:319–326. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90340-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deniau JM, Kitai ST, Donoghue JP, Grofova I. Neuronal interactions in the substantia nigra pars reticulata through axon collaterals of the projection neurons. An electrophysiological and morphological study. Exp. Brain Res. 1982;47:105–113. doi: 10.1007/BF00235891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzhala VI, Brumback AC, Staley KJ. Bumetanide enhances phenobarbital efficacy in a neonatal seizure model. Ann. Neurol. 2008;63:222–235. doi: 10.1002/ana.21229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon JH, Koziell DA, Moore RY. Catecholamine innervation of the basal fore-brain. II. Amygdala, suprarhinal cortex and entorhinal cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 1978;180:509–532. doi: 10.1002/cne.901800308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrant M, Kaila K. The cellular, molecular and ionic basis of GABA(A) receptor signalling. Prog. Brain Res. 2007;160:59–87. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)60005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari PF, Lowther S, Tidbury H, Greengrass P, Wilson CA, Horton RW. The influence of gender and age on neonatal rat hypothalamic 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 1999;19:775–784. doi: 10.1023/A:1006909207742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankfurt M, Fuchs E, Wuttke W. Sex differences in gamma-aminobutyric acid and glutamate concentrations in discrete rat brain nuclei. Neurosci. Lett. 1984;50:245–250. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(84)90493-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulou AS, Liptakova S, Velíšková J, Moshé SL. Sex and regional differences in the time and pattern of neurogenesis of the rat substantia nigra. Epilepsia. 2001;42(Suppl. 7):109. [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulou AS, Kyrozis A, Claudio OI, Stanton PK, Moshé SL. Sex-specific KCC2 expression and GABA(A) receptor function in rat substantia nigra. Exp. Neurol. 2003;183:628–637. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00213-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulou AS, Moshé SL. Role of sex hormones in the sexually dimorphic expression of KCC2 in rat substantia nigra. Exp. Neurol. 2003;184:1003–1009. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4886(03)00387-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulou AS. Sex- and cell-type-specific patterns of GABAA receptor and estradiol-mediated signaling in the immature rat substantia nigra. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006;23:2423–2430. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulou AS. Sexually dimorphic expression of KCC2 and GABA function. Epilepsy Res. 2008a;80:99–113. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulou AS. GABA(A) receptors in normal development and seizures: friends or foes? Curr. Neuropharmacology. 2008b;6:1–20. doi: 10.2174/157015908783769653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulou AS. Dissociated gender-specific effects of recurrent seizures on GABA signaling in CA1 pyramidal neurons: role of GABA(A) receptors. J. Neurosci. 2008c;28:1557–1567. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5180-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale K. Subcortical structures and pathways involved in convulsive seizure generation. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1992;9:264–277. doi: 10.1097/00004691-199204010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garant DS, Gale K. Substantia nigra-mediated anticonvulsant actions: role of nigral output pathways. Exp. Neurol. 1987;97:143–159. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(87)90289-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garant DS, Xu SG, Sperber EF, Moshé SL. Age-related differences in the effects of GABAA agonists microinjected into rat substantia nigra: pro- and anticonvulsant actions. Epilepsia. 1995;36:960–965. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1995.tb00953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Falgueras A, Pinos H, Collado P, Pasaro E, Fernandez R, Jordan CL, Segovia S, Guillamon A. The role of the androgen receptor in CNS masculinization. Brain Res. 2005;1035:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.11.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerfen CR. Basal ganglia. In: Paxinos G, editor. The Rat Nervous System. Third edition. Academic Press; S. Diego: 2004. pp. 458–510. [Google Scholar]

- Gingrich KJ, Roberts WA, Kass RS. Dependence of the GABAA receptor gating kinetics on the alpha-subunit isoform: implications for structure-function relations and synaptic transmission. J. Physiol. 1995;489:529–543. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi FS, Ferrucci M, Lazzeri G, Pizzanelli C, Lenzi P, Alessandrì MG, Murri L, Fornai F. A damage to locus coeruleus neurons converts sporadic seizures into self-sustaining limbic status epilepticus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2003;17:2593–2601. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi FS, Mauceli G, Blandini F, Ruggieri S, Paparelli A, Murri L, Fornai F. Locus coeruleus and neuronal plasticity in a model of focal limbic epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2006;47(Suppl. 5):21–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi FS, Velísková J, Chudomel O, Kyrozis A, Moshé SL. The role of substantia nigra pars reticulata in modulating clonic seizures is determined by testosterone levels during the immediate postnatal period. Neurobiol. Dis. 2007;25:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi FS, Blandini F, Cantafora E, Biagioni F, Armentero MT, Pasquali L, Orzi F, Murri L, Paparelli A, Fornai F. Activation of brain metabolism and fos during limbic seizures: the role of locus coeruleus. Neurobiol. Dis. 2008;30:388–399. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Hernández T, Rodríguez M. Compartmental organization and chemical profile of dopaminergic and GABAergic neurons in the substantia nigra of the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 2000;421:107–135. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000522)421:1<107::aid-cne7>3.3.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goy RW, McEwen BS. Sexual Differentiation of the Brain. MIT Press; Cambridge: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Grofova I, Deniau JM, Kitai ST. Morphology of the substantia nigra pars reticulata projection neurons intracellularly labeled with HRP. J. Comp. Neurol. 1982;208:352–368. doi: 10.1002/cne.902080406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzesiak M, Knapczyk-Stwora K, Duda M, Slomczynska M. Elevated level of 17β-estradiol is associated with overexpression of FSHR, CYP19A1, and CTNNB1 genes in porcine ovarian follicles after prenatal and neonatal flutamide exposure. Theriogenology. 2012;78:2050–2060. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2012.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulcebi MI, Ketenci S, Linke R, Hacıoğlu H, Yanalı H, Velíšková J, Moshé SL, Onat F, Çavdar S. Topographical connections of the substantia nigra pars reticulata to higher-order thalamic nuclei in the rat. Brain Res. Bull. 2012;87:312–318. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han TM, De Vries GJ. Organizational effects of testosterone, estradiol, and dihydrotestosterone on vasopressin mRNA expression in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. J. Neurobiol. 2003;54:502–510. doi: 10.1002/neu.10157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heida JG, Velísková J, Moshé SL. Blockade of androgen receptors is sufficient to alter the sexual differ, entiation of the substantia nigra pars reticulata seizure-controlling network. Epileptic Disord. 2008;10:8–12. doi: 10.1684/epd.2008.0160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadarola MJ, Gale K. Substantia nigra: site of anticonvulsant activity mediated by gamma-aminobutyric acid. Science. 1982;218(4578):1237–1240. doi: 10.1126/science.7146907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoi K, Sugimoto N. The brainstem noradrenergic systems in stress, anxiety and depression. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2010;22:355–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2010.01988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs BL, Azmitia EC. Structure and function of the brain serotonin system. Physiol. Rev. 1992;72:165–229. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobe PC, Mishra PK, Browning RA, Wang C, Adams-Curtis LE, Ko KH, Dailey JW. Noradrenergic abnormalities in the genetically epilepsy-prone rat. Brain Res. Bull. 1994;35:493–504. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)90163-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobe PC. Common pathogenic mechanisms between depression and epilepsy: an experimental perspective. Epilepsy Behav. 2003;4(Suppl. 3):14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2003.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BA, Watson NV. Spatial memory performance in androgen insensitive male rats. Physiol. Behav. 2005;85:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahle KT, Barnett SM, Sassower KC, Staley KJ. Decreased seizure activity in a human neonate treated with bumetanide, an inhibitor of the Na(+)-K(+)-2Cl(−) cotransporter NKCC1. J. Child Neurol. 2009;24:572–576. doi: 10.1177/0883073809333526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konkle AT, McCarthy MM. Developmental time course of estradiol, testosterone, and dihydrotestosterone levels in discrete regions of male and female rat brain. Endocrinology. 2011;152:223–235. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyrozis A, Reichling DB. Perforated-patch recording with gramicidin avoids artifactual changes in intracellular chloride concentration. J. Neurosci. Methods. 1995;57:27–35. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)00116-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyrozis A, Chudomel O, Moshé SL, Galanopoulou AS. Sex-dependent maturation of GABAA receptor-mediated synaptic events in rat substantia nigra reticulata. Neurosci. Lett. 2006;398:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lado FA, Moshé SL. How do seizures stop? Epilepsia. 2008;49:1651–1664. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lado FA, Velísek L, Moshé SL. The effect of electrical stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus on seizures is frequency dependent. Epilepsia. 2003;44:157–164. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.33802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie AM, Tingey JJ, Harrison NL, Pritchett DB, Twyman RE. Activation and deactivation rates of recombinant GABA(A) receptor channels are dependent on alpha-subunit isoform. Biophys. J. 1997;73:2518–2526. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78280-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman S. The generally accepted version of steroidogenesis is not free of uncertainties: other tenable and possibly superior renditions may be invented. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008;109:197–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löscher W, Czuczwar SJ, Jäckel R, Schwarz M. Effect of microinjections of gamma-vinyl GABA or isoniazid into substantia nigra on the development of amygdala kindling in rats. Exp. Neurol. 1987;95:622–638. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(87)90304-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason ST, Corcoran ME. Forebrain noradrenaline and metrazol-induced seizures. Life Sci. 1978;978:167–171. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(78)90266-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason ST, Corcoran ME. Depletion of brain noradrenaline, but not dopamine, by intracerebral 6-hydroxydopamine potentiates convulsions induced by electroshock. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1979;31:209–211. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1979.tb13480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazarati A, Shin D, Sankar R. Bumetanide inhibits rapid kindling in neonatal rats. Epilepsia. 2009;50:2117–2122. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Biegon A, Davis PG, Krey LC, Luine VN, McGinnis MY, Paden CM, Parsons B, Rainbow TC. Steroid hormones: humoral signals which alter brain cell properties and functions. Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 1982;38:41–92. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-571138-8.50007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Parsons B. Gonadal steroid action on the brain: neurochemistry and neuropharmacology. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1982;22:555–598. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.22.040182.003011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Permanence of brain sex differences and structural plasticity of the adult brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:7128–7130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre DC. Amygdala kindling in rats: facilitation after local amygdala norepinephrine depletion with 6-hydroxydopamine. Exp. Neurol. 1980;69:395–407. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(80)90222-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre DC, Edson N. Facilitation of amygdala kindling after norepinephrine depletion with 6-hydroxydopamine in rats. Exp. Neurol. 1981;74:748–757. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(81)90248-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirski MA, Fisher RS. Electrical stimulation of the mammillary nuclei increases seizure threshold to pentylenetetrazol in rats. Epilepsia. 1994;35:1309–1316. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1994.tb01803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra PK, Burger RL, Bettendorf AF, Browning RA, Jobe PC. Role of norepinephrine in forebrain and brainstem seizures: chemical lesioning of locus ceruleus with DSP4. Exp. Neurol. 1994;125:58–64. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1994.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler H. GABA(A) receptor diversity and pharmacology. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;326:505–516. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0284-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JA, Jordan CL, Dugger BN, Breedlove SM. Partial demasculinization of several brain regions in adult male (XY) rats with a dysfunctional androgen receptor gene. J. Comp. Neurol. 2005;487:217–226. doi: 10.1002/cne.20558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moshé SL, Albala BJ. Maturational changes in postictal refractoriness and seizure susceptibility in developing rats. Ann. Neurol. 1983;13:552–557. doi: 10.1002/ana.410130514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moshé SL, Albala BJ, Ackermann RF, Engel J., Jr. Increased seizure susceptibility of the immature brain. Brain Res. 1983:28381–28385. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(83)90083-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moshé SL, Albala BJ. Nigral muscimol infusions facilitate the development of seizures in immature rats. Brain Res. 1984;315:305–308. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(84)90165-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moshé SL, Brown LL, Kubová H, Velísková J, Zukin RS, Sperber EF. Maturation and segregation of brain networks that modify seizures. Brain Res. 1994;665:141–146. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91164-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moshé SL. Sex and the substantia nigra: administration, teaching, patient care, and research. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1997;14:484–494. doi: 10.1097/00004691-199711000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada R, Moshé SL, Wong BY, Sperber EF, Zhao DY. Age-related substantia nigra-mediated seizure facilitation. Exp. Neurol. 1986;93:180–187. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(86)90157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen RW, Sieghart W. GABA A receptors: subtypes provide diversity of function and pharmacology. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pati S, Sollman M, Fife TD, Ng YT. Diagnosis and management of epilepsy associated with hypothalamic hamartoma: an evidence-based systematic review. J. Child Neurol. 2013;28:909–916. doi: 10.1177/0883073813488673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrot-Sinal TS, Sinal CJ, Reader JC, Speert DB, McCarthy MM. Sex differences in the chloride cotransporters, NKCC1 and KCC2, in the developing hypothalamus. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2007;19:302–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2007.01530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perucca P, Camfield P, Camfield C. Does gender influence susceptibility and consequences of acquired epilepsies? Neurobiology of Disease. Special Issue Sex and Epileptogenesis. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.05.016. in this issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotkin MD, Snyder EY, Hebert SC, Delpire E. Expression of the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter is developmentally regulated in postnatal rat brains: a possible mechanism underlying GABA's excitatory role in immature brain. J. Neurobiol. 1997;33:781–795. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(19971120)33:6<781::aid-neu6>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravizza T, Velísková J, Moshé SL. Testosterone regulates androgen and estrogen receptor immunoreactivity in rat substantia nigra pars reticulata. Neurosci. Lett. 2003a;338:57–61. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)01317-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravizza T, Friedman LK, Moshé SL, Velísková J. Sex differences in GABA(A) ergic system in rat substantia nigra pars reticulata. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2003b;21:245–254. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(03)00069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera C, Voipio J, Payne JA, Ruusuvuori E, Lahtinen H, Lamsa K, Pirvola U, Saarma M, Kaila K. The K/Cl co-transporterKCC2 renders GABA hyperpolarizing during neuronal maturation. Nature. 1999;397:251–255. doi: 10.1038/16697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scantlebury MH, Galanopoulou AS, Velíšková J, Moshé SL. The substantia nigra in the control of seizures. In: Schwartzkroin PA, editor. Encyclopedia of Basic Epilepsy Research. Oxford. Vol. 2. Academic Press; 2009. pp. 846–854. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W. Activity of pars reticulata neurons of monkey substantia nigra in relation to motor, sensory, and complex events. J. Neurophys. 1986;55:660–677. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.55.4.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searles RV, Yoo MJ, He JR, Shen WB, Selmanoff M. Sex differences in GABA turnover and glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD(65) and GAD(67)) mRNA in the rat hypothalamus. Brain Res. 2000;878:11–19. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02648-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah NM, Jessell TM, Sanes JR. Sexual differentiation of the nervous system. In: Kandell ER, Schwartz JH, Jessell TM, Siegelbaum SA, Hudspeth AJ, editors. Principles of Neural Science. New York. Fifth edition McGraw-Hill; 2012. pp. 1306–1328. [Google Scholar]

- Shehab S, Coffey P, Dean P, Redgrave P. Regional expression of fos-like immunoreactivity following seizures induced by pentylenetetrazole and maximal electro-shock. Exp. Neurol. 1992;118:261–274. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(92)90183-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shughrue PJ, Dorsa DM. Estrogen and androgen differentially modulate the growth-associated protein GAP-43 (neuromodulin) messenger ribonucleic acid in postnatal rat brain. Endocrinology. 1994;134:1321–1328. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.3.8119173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira DC, Klein P, Ransil BJ, Liu Z, Hori A, Holmes GL, de La Calle S. Lateral asymmetry in activation of hypothalamic neurons with unilateral amygdaloid seizures. Epilepsia. 2000;41:34–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb01502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slob AK, Ooms MP, Vreeburg JT. Prenatal and early postnatal sex differences in plasma and gonadal testosterone and plasma luteinizing hormone in female and male rats. J. Endocrinol. 1980;87:81–87. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0870081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperber EF, Wong BY, Wurpel JN, Moshé SL. Nigral infusions of muscimol or bicuculline facilitate seizures in developing rats. Brain Res. 1987;465:243–250. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(87)90245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperber EF, Wurpel JN, Moshé SL. Evidence for the involvement of nigral GABAB receptors in seizures of rat pups. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 1989a;47:143–146. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(89)90117-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperber EF, Wurpel JN, Zaho DY, Moshé SL. Evidence for the involvement of nigral GABAB receptors in seizures of adult rats. Brain Res. 1989b;480:378–382. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90211-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperber EF, Velísková J, Germano IM, Friedman LK, Moshé SL. Age-dependent vulnerability to seizures. Adv. Neurol. 1999;79:161–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley KJ, Mody I. Shunting of excitatory input to dentate gyrus granule cells by a depolarizing GABAA receptor-mediated postsynaptic conductance. J. Neurophysiol. 1992;68:197–212. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanova N, Ovtscharoff W. Sexual dimorphism of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and the amygdala. Adv. Anat. Embryol. Cell Biol. 2000;158:1–78. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-57269-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabadi E. Functional neuroanatomy of the central noradrenergic system. J. Psychopharmacol. 2013;27:659–693. doi: 10.1177/0269881113490326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szot P, Weinshenker D, White SS, Robbins CA, Rust NC, Schwartzkroin PA, Palmiter RD. Norepinephrine-deficient mice have increased susceptibility to seizure-inducing stimuli. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:10985–10992. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-24-10985.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Luijtelaar G, Onat F, Gallagher MJ. Animal models of absence epilepsies: what do they model and does sex matter? Neurobiology of Disease. Special Issue Sex and Epileptogenesis. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.08.014. in this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhatalo S, Hellstrçm-Westas L, De Vries LS. Bumetanide for neonatal seizures: based on evidence or enthusiasm? Epilepsia. 2009;50:1289–1300. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velísek L, Velísková J, Ravizza T, Giorgi FS, Moshé SL. Circling behavior and [14C]2-deoxyglucose mapping in rats: possible implications for autistic repetitive behaviors. Neurobiol. Dis. 2005;18:346–355. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velísková J, Garant DS, Xu SG, Moshé SL. Further evidence of involvement of substantia nigra GABAB receptors in seizure suppression in developing rats. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 1994;79:297–300. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(94)90135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velísková J, Velísek L, Moshé SL. Subthalamic nucleus: a new anticonvulsant site in the brain. Neuroreport. 1996a;7:1786–1788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velísková J, Velísek L, Nunes ML, Moshé SL. Developmental regulation of regional functionality of substantial nigra GABAA receptors involved in seizures. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1996b;309:167–173. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00341-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velísková J, Kubová H, Friedman LK, Wu R, Sperber EF, Zukin RS, Moshé SL. The expression of GABA(A) receptor subunits in the substantia nigra is developmentally regulated and region-specific. Ital. J. Neurol. Sci. 1998a;19:205–210. doi: 10.1007/BF02427602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velísková J, Löscher W, Moshé SL. Regional and age-specific effects of zolpidem microinfusions in the substantia nigra on seizures. Epilepsy Res. 1998b;30:107–114. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(97)00096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velísková J, Moshé SL. Sexual dimorphism and developmental regulation of substantia nigra function. Ann. Neurol. 2001;50:596–601. doi: 10.1002/ana.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velísková J, Moshé SL. Update on the role of substantia nigra pars reticulata in the regulation of seizures. Epilepsy Curr. 2006;6:83–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1535-7511.2006.00106.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdoorn TA. Formation of heteromeric gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors containing two different alpha subunits. Mol. Pharmacol. 1994;45:475–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang DD, Kriegstein AR. GABA regulates excitatory synapse formation in the neocortex via NMDA receptor activation. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:5547–5558. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5599-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang DD, Kriegstein AR. Blocking early GABA depolarization with bumetanide results in permanent alterations in cortical circuits and sensorimotor gating deficits. Cereb. Cortex. 2011;21:574–587. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward IL, Weisz J. Differential effects of maternal stress on circulating levels of corticosterone, progesterone, and testosterone in male and female rat fetuses and their mothers. Endocrinology. 1984;114:1635–1644. doi: 10.1210/endo-114-5-1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz J, Ward IL. Plasma testosterone and progesterone titers of pregnant rats, their male and female fetuses, and neonatal offspring. Endocrinology. 1980;106:306–316. doi: 10.1210/endo-106-1-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]