ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

While most organizational literature has focused on initiatives that transpire inside the hospital walls, the redesign of American health care increasingly asks that health care institutions address matters outside their walls, targeting the health of populations. The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA)’s national effort to end Veteran homelessness represents an externally focused organizational endeavor.

OBJECTIVE

Our aim was to evaluate the role of organizational practices in the implementation of Housing First (HF), an evidence-based homeless intervention for chronically homeless individuals.

DESIGN

This was an interview-based comparative case study conducted across eight VA Medical Centers (VAMCs).

PARTICIPANTS

Front line staff, mid-level managers, and senior leaders at VA Medical Centers were interviewed between February and December 2012.

APPROACH

Using a structured narrative and numeric scoring, we assessed the correlation between successful HF implementation and organizational practices devised according to the organizational transformation model (OTM).

KEY RESULTS

Scoring results suggested a strong association between HF implementation and OTM practice. Strong impetus to house Veterans came from national leadership, reinforced by Medical Center directors closely tracking results. More effective Medical Center leaders differentiated themselves by joining front-line staff in the work (at public events and in process improvement exercises), by elevating homeless-knowledgeable persons into senior leadership, and by exerting themselves to resolve logistic challenges. Vertical alignment and horizontal integration advanced at sites that fostered work groups cutting across service lines and hierarchical levels. By contrast, weak alignment from top to bottom typically also hindered cooperation across departments. Staff commitment to ending homelessness was high, though sustainability planning was limited in this baseline year of observation.

CONCLUSION

Key organizational practices correlated with more successful implementation of HF for homeless Veterans. Medical Center directors substantively influenced the success of this endeavor through their actions to foster impetus, demonstrate commitment and support alignment and integration.

KEY WORDS: homeless persons, organizational behavior, implementation, community health, veterans, housing policy

There have been numerous scholarly efforts to describe factors conducive to adoption of evidence-based practices within health and social service settings.1–4 Much health care implementation literature focuses on initiatives within institutional walls, such as new treatment or safety programs.5,6 However, the redesign of American health care increasingly asks institutions to address matters outside their walls, targeting the health of defined populations.7,8 Factors driving this reorientation include readmission penalties,9 Accountable Care Organizations,10 bundled payments, and the chronic care model.11

For health care enterprises embracing a community endeavor, a key question is what organizational factors ensure success.2 Ongoing efforts by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to end Veteran homelessness provide an opportunity to study this question. In 2012, roughly 600,000 Americans went homeless each night, including 70,000 Veterans.12 Research evidence supports a new paradigm for intervention, Housing First (HF), featuring rapid provision of permanent supportive housing, strong recovery supports, without preconditions such as sobriety or treatment success.13 Research documents long-term housing success, with commensurate reductions in health service utilization.14–20

The largest national HF endeavor is VA’s supportive housing program (VASH), offering long-term supportive services to assist Veterans in obtaining and sustaining housing, with rental vouchers funded by US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). With over 58,000 HUD-VASH vouchers, this program requires individual VA Medical Centers (VAMCs) to find apartments for 500–1,500 Veterans across catchment areas covering hundreds of square miles. More importantly, the philosophical and operational endorsement of HF requires reorienting staff to prioritize the most vulnerable Veterans, to eschew traditional contingencies, and to expedite bureaucratic placement procedures.

The complexity and reach of the VA’s transition to the HF approach makes it an instructive example of how large-scale health care organizations may address social goals through intentional change. This paper details findings from the first year of the Homeless Solutions in a VA Environment (HSOLVE) study, a systematic effort to examine the organizational practices that most supported or impeded HF adoption. A previous publication describes operational challenges to housing itself.21 Here, we examine the organizational change factors associated with fidelity to the HF model.

METHODS

Study Design

This is an interview-based comparative case study conducted across eight VA Medical Centers (VAMCs) to assess (1) fidelity to HF in HUD-VASH programs in 2012, and (2) the degree to which elements favoring organizational change correlated with HF adoption. The data collection method of site visits and semi-structured interviews is typical in mental health program fidelity literature,22 in HF fidelity literature,23 and organizational change research.3,6,24,25

Site Selection

In consultation with VA partners, we recruited a purposive sample of eight VAMCs engaged in the national expansion of rental vouchers through the HUD-VASH program (identities of sites selected were not shared with VA leadership).26,27 Recruitment was regionally balanced, with a mixture of VAMCs managing larger and smaller voucher allocations, as well as intentional variation in regard to the size of the local homeless Veteran population and rental market conditions.

Interview Guide

A qualitative interview guide featured questions related to housing practices and organizational management. HF questions were based on an existing HF fidelity tool28 and refined by convening two expert panels (incorporating VA and non-VA national leaders in homelessness and HF), supplemented by a research team visit to Pathways to Housing (New York), a pre-eminent model.13,29 We crafted interview questions to track aspects of the HUD-VASH program expected to change under HF. However, to avoid social desirability bias, we did not explicitly mention “Housing First.” For example, to highlight whether programs sought the most vulnerable Veterans, we asked, “how do you identify and outreach to Veterans who need housing?” To elucidate potentially inappropriate contingencies, we asked whether clients must “demonstrate housing readiness to be eligible for housing placement.”

To explore organizational practices, questions were derived from the organizational transformation model (OTM).4,24 That framework emerged from study of quality improvement efforts across seven US health systems, and is included within the Consolidated Framework for organizational change.3 Domains of organizational transformation include: Impetus, Leadership commitment, Alignment throughout the organization (vertical), Integration across organizational boundaries (horizontal), Staff engagement, and Sustainability.24 Conceptual definitions and illustrations of each domain are offered in Table 1.

Table 1.

Domains of the Organizational Transformation Model

| Domain | Conceptual definitiona | Representative illustrations from datab |

|---|---|---|

| Impetus | Impetus is the sense of urgency needed to initiate and sustain the change process. | “Our facility is aligned with the Secretary to eliminate homelessness. The Secretary talks about rescue and prevention. The VA does rescue very well. We have opened the CRRC recently. They do rescue well. My focus is on prevention, on how to include the family in care—especially our most recent Veterans.” VAMC Director, A |

| “Although my involvement may not be as direct as some people, I certainly support the initiative. Taking care of patients means they have to have a safe place to live when they leave the hospital. I consider that part of the mission of the hospital.” Chief of Staff, B | ||

| Leadership commitment | Active leadership commitment is the work of senior executives, together with middle managers and opinion leaders, to orchestrate transformation by promoting conditions for change, specifying the direction in which the organization should move and spreading lessons of success and failure. | “The Director of the Hospital is very invested. She stages meetings of all homeless program staff. She asks what they need. She breaks through barriers.” Program Assistant, C |

| “There are some things I can make happen by virtue of my position: hiring, getting resources in the facility. It gets difficult, dicey sometimes. I meet weekly with [Chief of Mental Health] to remove any barriers in her way.”VAMC Director, A | ||

| “Been to a few meetings with frontline staff. They’re trying to set up a time for me to go on a ride to see who we’re serving and what it’s like. [Homeless Program Director] knows that she could come to me if there was anything I could do to help facilitate things.” VAMC Director, H | ||

| Alignment throughout organization (vertical) | Alignment is the consistency of plans, processes, information, resource decisions, actions, results and analysis to support key organization-wide goals—moving work at all levels of the organization in a consistent direction of shared purpose. | [Ending homelessness] is incorporated into administrative services—as part of their performance plan, they have to provide a narrative on what they have done to help end homelessness (ALL groups within the hospital, housekeeping, tech, everything links in to it). Philosophy is that everyone provides support to homeless services, as part of customer service/patient care services. Homeless services are a part of all performance plans. VAMC Director, D |

| “It’s about how to get the right people on the bus. I was fortunate to have people on the bus. The tough part of leadership—you have to make your goal clear across the organization. This a goal that has to be accomplished.” VAMC Director, B | ||

| “I chair the homeless committee with [HCHV Coordinator]. [She] is wonderful—really, really strong. We come to the table together and go over all the issues. Second issue—since most patients have mental health issues, I chair the Mental Health Council. Then, the Medical Center Director’s meeting. We hear reports regularly, once a month.” Chief of Staff, F | ||

| Integration across organizational boundaries (horizontal) | Integration is coordination and communication to bridge organizational boundaries between individual components (e.g., agencies, departments, functional areas) so that the components operate as an interconnected unit to support shared goals. | “The [Homeless Clinic] is multidisciplinary—we try not to have people think in their silos. That doesn’t work for the patients, because they need a team.” Chief of Staff, G |

| When she got here, services were in silos by discipline and all focused on chain of command. For example, a social worker told her that she couldn’t talk to her without her supervisor present. Different programs wouldn’t talk—no consult process. Program directors got together once a week, but there were no minutes. Now there is a Mental Health Council that meets once a week and keeps minutes. Chief of Mental Health, A | ||

| Staff engagement | Staff engagement is active participation in the change process and new programs through multi-disciplinary problem solving around concrete, meaningful, urgent issues. | “Ending homelessness by 2015: it’s a lofty goal, but we have to set the bar as high as we can. Can we do it? Probably not. But we’re going to work as hard as we can.” Supervisory Social Worker, G |

| “I have to tell you the truth—I’ve never been turned down. I know how to do it. I do all the footwork. I know everything they need, all the documents. I take them where they need to go to be connected to get deposit, I do all of that. Usually I can help with furniture, if the kids need something special, I can get that done.” Housing Specialist, F | ||

| Sustainability | Sustainability is the continuation of new programs or redesigned processes beyond the initial special attention and resources of the change effort or special project. | “I believe the infrastructure is strong enough for sustainability. Depends on the strength of the priority. When Central Office stops caring, we are likely to stop caring. If there’s a strong enough infrastructure then it’s sustainable.” Chief of Staff, F |

| No FTEs [temporary hires], all permanent. Can’t get qualified if using temporary positions. Case managers worry that once they house everyone they’ll be out of jobs, which will never happen. Facility is also concerned that they’ll have to pick up all the FTEs when the initiative ends. They’ve given us all this staff but haven’t built up all the other programs that need to support them throughout the rest of the hospital. You need more than just case managers to serve homeless. Homeless Program Director, E |

aConceptual domains of the Organizational Transformation Model are shown here. Assessment Criteria for these domains are shown in Appendix 2

bIllustrations presented include verbatim quotes (denoted by quotation marks) and summaries excerpted from notes taken in real-time during site-visit interviews

Data Collection Procedures

Once site leaders agreed to participate, we used snowball sampling to identify staff involved in delivering HUD-VASH housing.6,30 Approximately 10–14 persons (front line staff, mid-level managers, and VAMC leaders) were interviewed at each VAMC. At least two study team members were present for each interview to maximize topic coverage and to take near-verbatim notes. All interviewers were experienced in qualitative research and by design represented different backgrounds (homeless health care, sociology, social work, and organizational research). In total, 95 interviews were conducted at baseline (between February and December 2012). All interviews were voluntary and confidential, with approval from VA’s Central Institutional Review Board.

Data Analysis Procedures

The analysis approach combined development of a structured narrative to facilitate cross-site comparisons (similar to comparative qualitative analysis30,31) and consensus-based numeric fidelity ratings (for both HF and OTM), a method common to organizational implementation and fidelity research.6,24,32 This combination of analytic methods represents an evolving approach to case series analysis.31 It combines some advantages of rigorous (open-ended, in-depth) qualitative interpretation with a quantitative fidelity assessment.

To accomplish this, a structured case narrative was developed from the notes for each VAMC visited, including assessment criteria for the domains of HF (e.g., each consumer selects personalized goals according to their own values; see Appendix 1, available online) and domains of the Organizational Transformation Model (presented in Table 1; assessment criteria for these are offered as Appendix 2, available online). All team members who attended the site visit reviewed the narrative, offered revisions, and independently assigned fidelity scores on a 1 to 4 scale (4 indicating that the domain was fully implemented). The team reconciled scoring iteratively to arrive at final consensus-based ratings, adjusting the narrative if necessary to highlight pertinent justifications. Throughout this process, the team referred to detailed field notes to assure analytic integrity and consistency.

Partnerships

The funder, VA’s Health Services Research and Development Branch, mandated that the work be responsive to and collaborative with agency partners directly charged with supervising VA’s efforts to end homelessness. The research team and VA’s National Center on Homelessness Among Veterans sought to assure that this work would provide substantive insight to clinical leadership while assuring the study’s intellectual independence. The investigators obtained guidance from the Center to refine the study question and were assisted by them in convening the two expert panels. Results, preliminary and final, were reviewed and discussed with leadership. Importantly, the institutional partners were not investigators and did not have access to study data or to the identity of the study sites.

RESULTS

Quantitative Findings

VA Medical Centers in this study varied on several characteristics (see Table 2). Facility size, as measured by number of medical/surgical hospital beds, ranged from approximately 125 to over 275. These VAMCs had been allocated between 500 and 1,200 HUD-VASH vouchers, varying with catchment area geography and the number of homeless Veterans identified by Point-in-Time counts conducted annually. The majority of HUD-VASH vouchers had been allocated to chronically homeless Veterans, with three facilities allocating as many as 75 % to chronically homeless Veterans (well beyond the 67 % goal established by the VA). Average rents in the eight catchment areas ranged from $700 to over $1,600. Vacancy rates also ranged widely (from 3 to 10 %). Average rents and vacancy rates together help to illustrate the degree of rental market hardship, and they were comparable at each pair of facilities within a geographic region.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Eight VA Medical Centers Included in the HSOLVE Study

| Site | VAMC/community characteristics | Rental market conditions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of beds in VAMC | 2013 PiTa count estimate of homeless Veteran population in the VA catchment area | # of HUD-VASHb vouchers allocated to VAMCc | % of HUD-VASH vouchers distributed to chronically homeless Veteransc | Median price of rental unit in catchment aread | Rental vacancy rate in catchment aread | |

| Northeast/Mid-Atlantic Region | ||||||

| Site A | 175 | 700 | 1,000 | 65 % | $1,100 | 4 % |

| Site B | 175 | 2,100 | 1,200 | 55 % | $1,200 | 6 % |

| Southern Region | ||||||

| Site C | 125 | 375 | 500 | 75 % | $900 | 10 % |

| Site D | 225 | 1,100 | 1,100 | 55 % | $900 | 10 % |

| Midwestern Region | ||||||

| Site E | 250 | 600 | 500 | 50 % | $800 | 7 % |

| Site F | 275 | 550 | 500 | 50 % | $700 | 8 % |

| Western Region | ||||||

| Site G | 250 | 1,800 | 900 | 75 % | $1,400 | 3 % |

| Site H | 200 | 800 | 900 | 75 % | $1,600 | 3 % |

Note: All values are approximate to protect the confidentiality of study sites

aBased on data collected each year on a single night in January by local Continua of Care as directed by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development to estimate the size of the homeless population in each locale

bHUD-VASH refers to a combined program with subsidized rental vouchers provided by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and client selection and support provided by the Department of Veterans Affairs, termed VA Supportive Housing (VASH)

cBased on internal VA data

dBased on data publically available from HUD

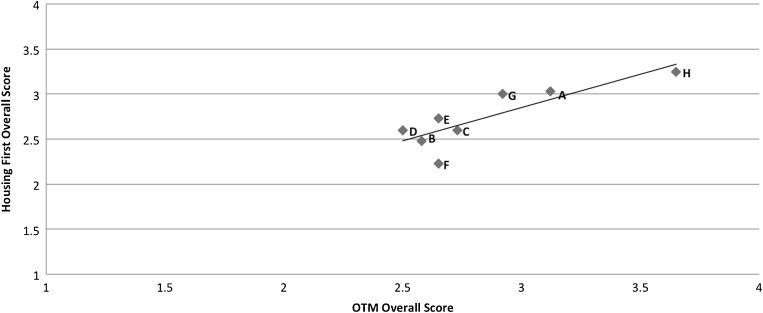

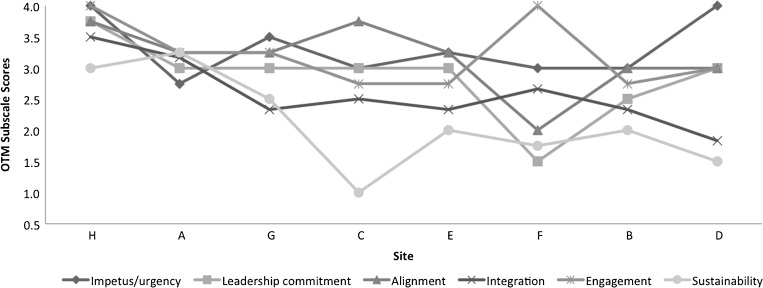

Table 3 shows that there was variation in HF overall scores (range = 2.23–3.25), indicating meaningful variation in the degree of fidelity to HF practices. There was similar variation in OTM scores (range = 2.50–3.65) across sites. Figure 1 depicts a positive, linear association between the HF and OTM overall scores. HF implementation was strongest where organizational practices most strongly aligned with components of the OTM, and vice versa. Although three sites (A, G, H) did separate modestly from the rest, there were examples of stronger and weaker practice (in both the OTM and HF domains) across all sites we studied. Figure 2 presents the OTM subscale scores at each site. The three sites scoring best with regard to HF practices (A, G, H) tended to be strong on all components of the OTM; two of these sites were in the West, and scored well despite adverse rental markets (Table 1). Lower ranked sites showed greater variability in organizational practices (most notably C, D and F), scoring well on some aspects and poorly on others; two of these were in the South, and had somewhat more favorable rental markets. Across all sites, scores were typically higher for the domain of (vertical) Alignment and lower for Sustainability. These quantitative findings support our expectation regarding the association between strong organizational practices and successful HF implementation, illustrated below by our qualitative findings.

Table 3.

Overall Housing First (HF) Fidelity Scores and Organizational Transformation Model (OTM) Scores at Eight VA Medical Centers Included in the HSOLVE Study

| Site | Region | HF ranking (score) | OTM ranking (score) | Organizational transformation model subscores | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impetus | Leadership commitment | Alignment | Integration | Engagement | Sustain-ability | ||||

| Site H | W | 1 (3.25) | 1 (3.65) | 4.00 | 3.75 | 3.75 | 3.50 | 4.00 | 3.00 |

| Site A | NE | 2 (3.03) | 2 (3.12) | 2.75 | 3.00 | 3.25 | 3.17 | 3.25 | 3.25 |

| Site G | W | 3 (3.00) | 3 (2.92) | 3.50 | 3.00 | 3.25 | 2.33 | 3.25 | 2.50 |

| Site C | S | 5 (2.60) | 4 (2.73) | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.75 | 2.50 | 2.75 | 1.00 |

| Site E | MW | 4 (2.73) | 5 (2.65) | 3.25 | 3.00 | 3.25 | 2.33 | 2.75 | 2.00 |

| Site F | MW | 8 (2.23) | 5 (2.65) | 3.00 | 1.50 | 2.00 | 2.67 | 4.00 | 1.75 |

| Site B | NE | 7 (2.48) | 7 (2.58) | 3.00 | 2.50 | 3.00 | 2.33 | 2.75 | 2.00 |

| Site D | S | 5 (2.60) | 8 (2.50) | 4.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 1.83 | 3.00 | 1.50 |

Note: HF housing first, OTM organizational transformation model. Regions are NE (Northeast/Mid-Atlantic), S (South), MW (Midwest), W (West)

Figure 1.

Association between overall OTM scores and housing first scores at eight VA Medical Centers included in the HSOLVE study.

Figure 2.

OTM subscale scores at eight VA Medical Centers included in the HSOLVE study.

Qualitative Findings

Below, we explore variations among sites for each of the organizational practice domains, with emphasis on practices that appear to have influenced HF fidelity. Illustrative findings are shown in the far right column of Table 1.

Impetus

All sites were subject to similar external pressure to adopt HF, likely attenuating the degree of variation in impetus across sites. That external pressure included declarations by the Secretary of Veterans Affairs regarding the goal to end Veteran homelessness, provision of resources to do so, and performance tracking of key outcomes for the homeless programs (i.e., percentage of allocated vouchers that had been used to lease an apartment and the percentage of vouchers distributed to chronically homeless Veterans) by VA’s national homeless leadership. While some Medical Center leaders expressed reservations about aspects of the goal, such as the emphasis on the chronically homeless, all endorsed the cause of housing vulnerable Veterans, even though at baseline few leaders could describe distinctive characteristics of the HF approach.

The VA’s use of performance tracking reinforced accountability expectations. Medical center directors’ performance evaluations and compensation were based, in part, on these results. Across all study sites, senior leaders aggressively monitored the numbers reported by the homeless programs. In sites that were struggling to meet the two key measures, performance was monitored even more frequently; several sites included homeless program managers in daily executive meetings to receive constant updates on the numbers.

This intense focus on measures by Medical Center leaders reinforced a sense of urgency among all staff. However, strict emphasis on numeric results held some risk. One case manager (D) described informally having clients start case management without directing them to a voucher until they were ready to quickly find an apartment (which would reduce the apparent time lag between issuing vouchers and signing a lease, a component of the “leased up” performance measure). Such practice conflicts with HF’s rejection of “housing readiness” criteria. Additionally, staff complained that senior leaders rarely comprehended the complex challenges of housing chronically homeless Veterans and how that impacted numeric outcomes (C, D).

Leadership Commitment

One way senior leaders reinforced key initiatives was by spending their own time on activities supporting change efforts.24,25 Perhaps the most public demonstration of leadership commitment observed in this study, reported most notably at sites A and F, was the physical presence of Medical Center directors at important homeless-related events (such as Stand Downs and annual Point-in-Time counts of homeless individuals in the community).

Several examples of leadership commitment were observed at site H, including the crucial support of setting aside additional discretionary funding to enhance the effort. This director routinely communicated directly with housing program managers and staff to identify issues and tangibly support their work. This director also strongly affirmed a personal responsibility to resolve problems related to hiring space, security, vehicles, information technology and matters involving non-VA officials. These responsibilities were acknowledged (at least tacitly) by all Medical Center directors, but none so emphatically. The director at Site H offered career recognition for existing staff, acknowledging that s/he understood the creativity of the staff in addressing challenges.

A separate and powerful expression of support was found in the selection of crucial department chiefs. Leaders at one Medical Center (E) chose an individual experienced in homeless issues for a senior leadership position, which ultimately impacted both integration and alignment as noted below. Leadership commitment also emerged from key middle managers serving as project “champions” and instrumental program leaders. Site A selected a new clinical manager for Mental Health (where homeless programs were located) with experience and passion for homeless issues. Directly supervising the homeless program, this manager established internal program goals, maximized efficiency, and solved operational problems wherever possible. This manager also advocated for homeless programs and for taking advantage of resources to improve the integration of services for homeless and newly housed Veterans. The new Mental Health manager reported to the chief of staff, who fully supported her/him programmatically by making his/her areas of responsibility (mental health, social service, homeless programs) equal partners at the clinical leadership table.

Alignment

Alignment involves directing efforts at all levels of the organization—top to bottom—to assure that there are consistent plans, processes, and actions in place.4 Leaders at the high performing sites contributed to alignment through their constant attention to the goal of housing homeless Veterans, communicating the goal widely, and directly asking how they could help (C). A common mechanism across Medical Centers was the inclusion of homelessness in institutional messages and town meetings. Some sites, most notably C and F, also included representatives from the homeless programs at top-level meetings involving departmental leaders from throughout the Medical Center, or assembled workgroups that included mid-level and senior leaders from across the organization (e.g., a “Mental Health Council”). Both of these mechanisms allowed new concerns to gain the attention of senior leadership without having to overcome potential resistance that can emerge in strictly enforced “up-the-chain” reporting mechanisms. At Site D, efforts to address Veteran homelessness were included on performance evaluations for all departments, from housekeeping to primary care. These actions demonstrated that leadership genuinely expected all levels of the organization to be actively involved in the goal of housing homeless Veterans.

Integration

Multidisciplinary clinical teams (including social workers, nurses/physicians, psychiatrists, substance abuse specialists, etc.) are central to the HF approach, and their development required relaxing traditional disciplinary divisions; such changes had to be approved, if not directed, from the top. Many sites had obtained funds for Community Resource and Referral Centers (A, C, D, E, F) to physically co-locate multiple components of their homeless services (including case management, primary care, mental health). Site D restructured reporting relationships by moving homeless programs out from another department and into Mental Health to expedite interaction between homeless and mental health staff. More broadly, many sites had adopted a “no wrong door” approach, in which homeless Veterans presenting to any department within the VAMC would be actively encouraged to take advantage of the homeless services available, often through a direct “warm hand-off” to the homeless services team from another professional. A common concern, however, was that assigning homelessness to one department or service (Mental Health, most typically) fostered unhelpfully narrow understandings of homelessness as purely a “mental health” issue (E).

External integration (across organizations) was also central to meeting the rapid housing goal of HF. The process of obtaining an apartment involves interactions with community agencies, notably local public housing authorities (PHAs). High-scoring study sites recognized the need to improve coordination with community agencies and took affirmative steps to improve it, resulting in more rapid housing. Several study sites (A, G, H) designated staff to serve as points of contact between the VA and the public housing authority staff. Better performing sites reported that senior leaders maintained relationships with elected municipal, county, and state leaders or had established traditions of VA membership on key homeless-focused state or municipal Boards (A, E, G). These political relationships sometimes opened up new opportunities for VA programs, such as the development of a Community Resource and Referral Center that jointly served both city and VA-specific needs (C).

Despite the conceptual distinction between alignment and integration, some organizational practices have the potential to alter both either favorably or unfavorably. For example, Site H scored well on both because it enlisted an analyst within the Director’s Office to maintain continuous contact between senior leadership and the homeless programs (bypassing standard chain of command), with a focus on troubleshooting and identifying problems early. This allowed the Medical Center director access to early indication of problems when they occurred and assured facilitation of departmental collaboration when necessary. As an example of negative alignment that impaired integration, another site rented space for its housing staff that removed them from the clinical environment into a building whose security forbade in-person visits with clients. In this instance, the decision to move to the isolated and isolating rental space implied a misalignment between front-line staff (who needed to see their clients) and leadership. This step impeded integration of service between housing staff and the medical providers with whom they had formerly shared space.

Staff Engagement

Full engagement of staff, especially those on the front line, is essential to the success of organizational change efforts. While staff engagement often results from strong impetus and leadership commitment in a top-down fashion, knowledge of HF was relatively limited among senior leadership during the year of our baseline visits. Rather, it appeared that staff engagement grew primarily out of the deep, intrinsic commitment to serving Veterans that was shared among nearly all front-line staff we interviewed. Nearly all staff spoke passionately about the work they do, while acknowledging the challenges and disappointments that were a constant part of the job. In situations in which the extremely tight housing market made the task of finding suitable apartments almost impossible, such as Site G, there was a mild undercurrent of frustration with the insurmountability of the task, though this was balanced by a strong commitment to supporting Veterans while they waited on housing opportunities. In some sites, staff had reservations about new approaches embedded in HF, such as housing Veterans who were still active substance abusers (D). Those who were unable to adapt appeared to self-select out of homeless services, allowing relatively inexperienced but highly committed and energetic staff to become more central; at Site D, for example, one case manager spoke of “old-timers” as being those case managers with three years of experience in homeless services.

Sustainability

Sustainability involved two interrelated concepts in this study. The first concerned sustaining program innovations, including the much-expanded staff for homeless programs. The second concerned sustaining individual Veterans in housing, despite threats (mental or financial) to stability. There was relatively little planning for sustaining efforts to expand the programs, as nearly all attention focused on reporting the percentage of vouchers leased up in the short term. Each site we visited was keenly aware that of the challenge arising from uncertainty regarding future Congressional allocations and appropriations, particularly those attached to this special initiative. As a result, Medical Centers commonly engaged in tactical planning to avoid long-term budgetary exposure for the homeless program expansions. This involved hiring employees limited to a term of 24 months or even less, a move that reflected understandable budgetary caution, but which also created considerable tension with long-term planning for homeless programs in particular.

DISCUSSION

This study sought to determine whether organizational practices facilitate adoption of an evidence-based approach to ending homelessness (Housing First, HF) among VAMCs. Key organizational practices (ranging from leadership commitment to alignment and integration) correlated with more successful implementation of HF. When those practices were combined as a single score summarizing the research team’s observations, a nearly linear relationship was observed between variations in the Organizational Transformation Model (OTM) and HF scores. However the OTM assessment, involving multiple scales, embodies a multifaceted understanding of how organizational leadership facilitates change, and examples of both strong and weak practice were found across all sites. In this study, the effort to “make Housing First happen” typically reflected a division of duties. VAMC directors typically were well positioned to directly influence the mechanics of achieving housing rapidly and assuring the collaboration of multidisciplinary supportive services. These elements lie within the directors’ grasp because they can influence leadership hiring/promotion, resource allocation, and service configurations organizationally and geographically. In this first round of study, we did not find that VAMC directors had specific knowledge of the harm reduction philosophy at the heart of HF. However, this component was communicated by national leadership to mid-level managers in charge of housing programs.

In this study, impetus was conveyed by vigorous goal statements from senior leadership, coupled with resources and measurement of results. Leadership commitment at the institutional level varied. Some, but not all, Medical Center leaders joined the front-line staff in public shows of support, and elevated mid-level managers who could champion homeless issues. For this initiative, the designated champions were granted high levels of access to senior leadership, even when their formal position fell lower in the organizational hierarchy.

Vertical alignment of effort and horizontal integration were closely interrelated in practice, in part because poor alignment from top to bottom hindered cooperation across departments. In this study, staff commitment was routinely high. However, a long-term risk was suggested by the relative lack of sustainability planning for the housing initiative beyond the end date, a challenge consistently encountered in nonprofit and government-sponsored initiatives.

These findings must, of necessity, be qualified. The study itself is a formative, qualitative exercise in which numerical scores summarize assessments involving a significant degree of subjectivity, despite careful use of feedback and consensus among the research team. The qualitative variations reported here have not yet been tested against numeric measures of clients’ housing success, a matter for future work by this team. Despite the correlations observed here, it remains possible that strong housing practices and strong organizational practices coexist without a relevant causal relationship. It must also be noted that this report includes observations from baseline visits (2012), prior to additional dissemination projects by the VA’s national leadership.

Partnering as a Dimension of this Research Project

This ongoing study is one of four directly mandated by the VA to pursue a path of “partnering” in research, though partnering was not defined, a priori, by the funder or by the investigators. Both the research team and VA’s National Center on Homelessness Among Veterans sought to assure that this work would provide substantive insight to clinical leadership, while retaining intellectual independence and protecting the confidentiality of participating sites that readily saw the clinical partner as a supervising agency within the institutional hierarchy. Similarly, the research team was neither funded by VA’s central management nor geographically proximal to it. The downside of this particular arrangement was that the research team could not easily serve in the role of an operational consultant to management. The benefit, however, was that resulting research insights could be considered fully uncontaminated by investments or political interests of the funders, and this arrangement was seen as mutually desirable by both the VA partners charged with implementing HF, and the research team. The research team sought to return something of value to the organizational partner, including interim reports, and draft manuscripts and final products at regular intervals.

Implications

Hospitals, traditionally focused on medical care, do not typically lead efforts to solve large social problems. In this regard, the VA’s reliance on its own network of over 150 Medical Centers could seem exceptional. However, health care institutions rarely operate with complete freedom from the social and contextual determinants of health and health care. Moreover, national policies increasingly seek to foster organizations accountable for the care of populations. Such policies invite attention to the social determinants of health, many of which drive hospital readmission and emergency department utilization, two phenomena in which the homeless exert disproportionate impact.33,34 When health care providers collaborate in community-wide efforts to address major social challenges, this study suggests that success or failure at least partly depends on impetus, and on the degree to which organizational leaders demonstrate commitment, foster alignment, integration, and engagement.

Acknowledgements and Disclosures

This study was funded by grant SDR-11233 from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development branch. The authors thank the many VA staff who graciously shared their observations and experiences with this research team. The authors also thank Vincent Kane, MSW, National Center on Homelessness Among Veterans, Department of Veterans Affairs, and Keith Harris, PhD, National Director of Clinical Operations, Mental Health Homeless and Residential Rehabilitation Treatment Programs, Department of Veterans Affairs, for their partnership in this study. They also thank N. Kay Johnson, BSN, MPH and Carolyn Ray, JD for their assistance with the study.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent the positions of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Appendix 1: Assessment Criteria for Domains of Housing First

| 1. Housing assistance is the key intervention for ending homelessness | 2. Consumer choice and self-determination are central | 3. Housing is targeted to the most vulnerable consumers first | 4. A full range of services should be available to consumers though housing is not contingent on treatment participation or success | 5. Consumers are seen as able to take incremental steps toward positive behavior change and reduced harm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Housing and services are functionally separate | 2.1 Each consumer sets personalized goals according to their own values | 3.1 Prioritizes chronically homeless consumers using formally established criteria | 4.1 No preconditions for housing readiness | 5.1 Consumer selects the sequence, duration, and intensity of services |

| 1.2 Time to housing is minimized | 2.2 Consumers select a residence from among other options with choice in type and location of residence | 3.2 Prioritizes consumers with complex medical and/or psychological needs | 4.2 Multidisciplinary service teams (including persons such as nurses, doctors, employment specialists, peer specialists) provide individualized services | 5.2 Motivational interviewing is used to help consumers identify and meet their self-defined goals |

| 1.3 Housing is permanent | 2.3 No institutional housing | 3.3 Well-developed systems to identify and outreach to consumers who need housing | 4.3 There are regular face-to-face encounters between staff and consumers | |

| 1.4 Specific assistance for the client with locating and securing housing is offered | 2.4 No live-in staff | 3.4 Services are adjusted during times of crisis | 4.4 Support services are available 24/7 | |

| 1.5 Additional placement opportunities are offered when an initial housing placement has failed | 2.5 Occupancy arrangements are standard for the market | 3.5 Support is provided to local community (especially landlords, property managers) for dealing with hard-to-house consumers | 4.5 Strength-based orientation in all services provided | |

| 3.6 Staff have the capacity to meet the needs of highly vulnerable consumers | 4.6 Continuation of support services if the consumer leaves housing or is hospitalized |

Appendix 2: Assessment Criteria for Domains in the Organizational Transformation Model

| 1. Impetus | 2. Leadership commitment | 3. Alignment throughout organization (vertical) | 4. Integration across organizational boundaries (horizontal) | 5. Staff engagement | 6. Sustainability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Strong impetus among Medical Center leadership to implement HF and/or to meet VA goals for ending Veteran homelessness | 2.1 Medical center leadership provides vision and direction, demonstrate constancy of purpose for HF implementation | 3.1 Alignment of goals regarding HF throughout the Medical Center | 4.1 Presence of high-level structures to facilitate cooperation across organizational boundaries; coordinate staff providing services for homeless Veterans. | 5.1 Staff buy-in for national, local mandates for housing homeless Veterans. | 6.1 Attention to sustaining progress achieved in meeting goals. |

| 1.2 Urgency, sense of impetus among mid-level managers | 2.2 Department chiefs and mid-level managers demonstrate support of HF goals and activities | 3.2 Measurement of progress and success of HF activities | 4.2 Progress and lessons learned are shared across the Medical Center | 5.2 Motivational interviewing is used to help consumers identify and meet their self-defined goals | 6.2 Attention to maintaining Veterans in housing |

| 4.3 Efforts to ensure engagement/alignment with external organizations |

REFERENCES

- 1.Kaplan HC, Brady PW, Dritz MC, et al. The influence of context on quality improvement success in health care: a systematic review of the literature. The Milbank Quarterly. 2010;88:500–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2010.00611.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. The Milbank Quarterly. 2004;82:581–629. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Deusen LC, Holmes SK, Cohen AB, et al. Transformational change in health care systems: an organizational model. Health Care Manage Rev. 2007;32:309–320. doi: 10.1097/01.HMR.0000296785.29718.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordon AJ, Trafton JA, Saxon AJ, et al. Implementation of buprenorphine in the Veterans Health Administration: results of the first 3 years. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90:292–296. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Damschroder LJ, Lowery JC. Evaluation of a large-scale weight management program using the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR) Implementation Science. 2013;8:51. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devore S, Champion RW. Driving population health through accountable care organizations. Health Affairs. 2011;30:41–50. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Affairs. 2008;27:759–769. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calvillo-King L, Arnold D, Eubank KJ, et al. Impact of social factors on risk of readmission or mortality in pneumonia and heart failure: systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:269–282. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2235-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woods ER, Bhaumik U, Sommer SJ, et al. Community asthma initiative: evaluation of a quality improvement program for comprehensive asthma care. Pediatrics. 2012;129:465–472. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002;288:1775–1779. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Office of Planning and Community Development . The 2013 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress, Part 1: Point-in-Time Estimates of Homelessness. Washington, DC: United States Department of Housing and Urban Development; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsemberis S, Gulcur L, Nakae M. Housing First, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:651–656. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.4.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng A-L, Lin H, Kasprow W, Rosenheck R. Impact of supported housing on clinical outcomes: analysis of a randomized trial using multiple imputation technique. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195:83–88. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000252313.49043.f2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larimer ME, Malone DK, Garner MD, et al. Health care and public service use and costs before and after provision of housing for chronically homeless persons with severe alcohol problems. JAMA. 2009;301:1349–1357. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Srebnik D, Connor T, Sylla L. A pilot study of the impact of Housing First-Supported Housing for intensive users of Medicaid hospitalization and sobering services. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:316–321. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sadowski LS, Kee RA, VanderWeele TJ, Buchanan D. Effect of a housing and case management program on emergency department visits and hospitalizations among chronically ill homeless adults: a randomized trial. JAMA 2009;301. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Mares AS, Rosenheck RA. A comparison of treatment outcomes among chronically homeless adults receiving comprehensive housing and health care services versus usual local care. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38:459–475. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0333-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsai J, Kasprow WJ, Rosenheck RA. Alcohol and drug use disorders among homeless veterans: prevalence and association with supported housing outcomes. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39:455–460. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwang SW, Gogosis E, Chambers C, Dunn JR, Hoch JS, Aubry T. Health status, quality of life, residential stability, substance use, and health care utilization among adults applying to a supportive housing program. Journal of Urban Health. 2011;88:1076–1090. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9592-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Austin EL, Pollio DE, Holmes S, et al. VA’s expansion of supportive housing: successes and challenges on the path toward Housing First. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65:641–647. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McHugo GJ, Drake RE, Whitley R, et al. Fidelity outcomes in the National Implementing Evidence-Based Practices Project. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:1279–1284. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.10.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelson G, Stefancic A, Rae J, et al. Early implementation evaluation of a multi-site housing first intervention for homeless people with mental illness: a mixed methods approach. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2014;43:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.VanDeusen LC, Engle RL, Holmes SK, et al. Strengthening organizations to implement evidence-based clinical practices. Health Care Manage Rev. 2010;35:235–245. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0b013e3181dde6a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.VanDeusen LC, Holmes SK, Cohen AB, et al. Transformational change in health care systems: an organizational model. Health Care Manage Rev. 2007;32:309–320. doi: 10.1097/01.HMR.0000296785.29718.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kasprow WJ, Cuerdon T, DiLella D, Cavallaro L, Harelik N. Health Care for Homeless Veterans Programs: Twenty-Third Annual Report. Department of Veterans Affairs: West Haven, CT; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Office of Community Planning and Development . The 2011 Point-in-Time Estimates of Homelessness: Supplement to the Annual Homeless Assessment Report. Washington, DC: United States Department of Housing and Urban Development; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilmer TP, Stefancic A, Sklar M, Tsemberis S. Development and validation of a Housing First fidelity survey. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64:911–914. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsemberis S. Housing First: The Pathways Model to End Homelessness for People with Metal Illness and Addiction. Hazelden: Center City; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage, Inc.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rihoux B. Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) and Related Systematic Comparative Methods: Recent Advances and Remaining Challenges for Social Science Research. International Sociology. 2006;21:679–706. doi: 10.1177/0268580906067836. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bond GR, McHugo GJ, Becker DR, Rapp CA, Whitley R. Fidelity of supported employment: lessons learned from the National Evidence-Based Practice Project. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2008;31:300–305. doi: 10.2975/31.4.2008.300.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buck DS, Brown CA, Mortensen K, Riggs JW, Franzini L. Comparing homeless and domiciled patients’ utilization of the harris county, Texas public hospital system. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23:1660–1670. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kushel MB, Perry S, Bangsberg D, Clark R, Moss AR. Emergency department use among the homeless and marginally housed: results from a community-based study. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:778–784. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.5.778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]